MRY

Wormwood Studios

Maybe "play by the book" means "use a walkthrough." :D

Lamplight City promises a detective story where you can screw up everything

By John Walker on March 28th, 2018 at 7:00 pm

After the delights of sci-fi adventure Shardlight we were always going to be interested in what Francisco Gonzalez did next. Now having played a small section of his follow-up, Lamplight City, I can confirm such anticipation is well merited. This is a steampunk detective adventure where messing everything up is an entirely legitimate way to play.

Following the news that Dave Gilbert and Francisco Gonzalez were no longer working together, there were at one point concerns for the future of Lamplight City. Concerns be put aside, because we’re in for a treat of a 2018, with not just Gilbert’s own RPG-influenced approach to the genre in Unavowed, but also Gonzalez realising his own vision for adapting the traditional point-and-click adventure, in a game he’s not only written, but also painted and animated.

Lamplight is a detective story featuring multiple cases for PI Miles Fordham, an ex-cop who’s seemingly haunted by his former partner. Set in an alternative version of the 19th century, in the industrially advanced New Bretagne, Fordham’s first case seems relatively benign. A flower shop is being routinely broken into, flowers stolen, but then the money to pay for them left inside. The owner refuses to call the police, simply because the situation is so bizarre, so her assistant defies her wishes by getting in a PI. As you might suspect, the case turns sour, someone is killed, and Fordham finds himself muddled in a peculiar mystery while apparently losing his mind.

But what’s rather intriguing here is, inspired by the more recent Sherlock Holmes games (in this concept alone, thank goodness), Lamplight makes it possible for you to misinterpret a case’s evidence, or miss vital clues, and yet still be able to play. In fact, you can completely fail to solve a case, just mess up a big section of the game entirely, and yet continue on despite this. The game will, says Gonzalez, adapt to your mistakes and play out differently depending upon your successes and failures. It’s even possible to so colossally screw everything up that you can not even play the game’s climactic chapter, and receive an entirely negative ending instead.

The game also does away with the inventory, which may or may not appeal to you. I was surprised at first, solving a puzzle involving opening a window after realising I needed to find a sharp object that could fit in the hole. When I returned to it with a basket hook from the flower shop, I only needed to click on the window to have it be used. Which, at first, felt odd, until I recognised what a perfunctory act it would have been to use the thing I knew was needed here in the place I knew it was needed. Sure, yes, automate that! Will it diminish later puzzles? We don’t yet know, but the game’s promise to offer difficulty such that you can be led down entirely incorrect garden paths suggests its complexity will be found elsewhere.

It looks great – the enormously talented Ben Chandler provided the backgrounds and animations for Shardlight, but this time Gonzalez has done it all himself. And gosh, he’s multi-talented. The voice acting I saw from the opening chapter is superb too, with the banter between the leads often funny, and always well delivered. What I wasn’t able to get an impression of from this preview was how the core game itself will play, how it will feel to get involved in mysteries you might muddle your way out of being able to solve. That’s a complicated balance to get right, and I strongly hope Lamplight will find it, because everything else about it is looking so promising.

It’s interesting that both Gonzalez and Gilbert have approached replayability in a traditionally one-and-done genre in such different ways. Unavowed opts for multiple solutions to situations, with varying characters and different player backgrounds, while Lamplight City has so much freedom for the player to interpret cases their own way. Both approaches mean the game can be played all over again with different experiences, and perhaps more crucially for smaller indie projects with a narrative focus, it means both remain worth playing after someone’s watched a stream of the game. It’s fascinating that such excesses are seemingly becoming vital in our Twitchy future.

It’s also interesting that the creaky old Adventure Game Studio engine is seeing such fresh life put into it, at the same time as its own improvements mean games can run at higher resolutions with double the pixel count (don’t get excited – not modern resolutions, it’s just escaped from its previous 640×480 prison).

Lamplight City is due out this summer, and from the snippet I’ve played, is looking extremely good.

Lamplight City: A Detective Game Where It's Okay To Fail

Note: In March of 2017, I presented a talk at GDC in San Francisco as part of a presentation called "The Narrative Innovation Showcase." This post is more or less what I spoke about during that talk.

For the past 2 years, I've been working on my new game, Lamplight City. The elevator pitch I've come up with is "a detective game where it's okay to fail," but what does that mean exactly?

Lamplight City is a detective adventure set in an alternate steampunk-ish “Victorian” past (Since it’s alternate history, that’s why “Victorian” is in quotes) The game is divided up into 5 cases, but features one overarching narrative. Each case features multiple suspects, false leads, moral choices, and lasting consequences, and the general atmosphere and tone of the game is inspired by the works of Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Dickens.

In Lamplight City, you play as a former detective turned private investigator named Miles Fordham, whose partner Bill is killed at the start of the game. Miles begins hearing Bill’s voice in his head, and slowly begins losing his grip on sanity. He is convinced that the only way to get rid of the voice and let his partner move on is to find the person responsible for Bill’s death, although he has no real leads, and also feels guilty and blames himself. Miles keeps himself distracted and hopes to find some link to Bill’s killer by taking on other cases, which make up the bulk of the gameplay. Each case has different leads to follow and different potential suspects. It’s your job as the player to do some actual detective work and figure out which of the leads are useful, which are red herrings, and who actually did it. In some cases you might be called upon to make moral decisions and determine if the person who actually did it deserves to be punished for their crime.

The main thing I wanted to explore and experiment with in Lamplight City was figuring out how to make a detective game with multiple solutions and paths where failure was an option, but also still an enjoyable gameplay experience. I noticed that in most games of this type, you always arrive at the correct solution, no matter what. You’re not allowed to be wrong, and a lot of the time the game will go to incredible lengths to make sure you win.

Two examples of note are L.A. Noire and Sherlock Holmes: Crimes and Punishments. Both games have a multi-case structure with an overarching storyline. In Crimes and Punishments, each case has several suspects to pick from, and it’s possible to pick incorrectly. In L.A. Noire, some cases also present multiple suspects, but only on one or two occasions does the game actually allow you a choice of who to accuse.

However, neither of these games ever allow you to get things completely wrong. If Sherlock picks the wrong suspect, the game moves on as if nothing happens, the only consequence being he gets an angry letter from a relative of the accused. Since he is Sherlock, he isn’t really allowed to fail. If a witness is called out on a lie and you pick the wrong option, you simply get to try again.

The same thing happens in L.A. Noire. In addition to that, if you follow a lead and the game has you do something like tail a suspect or begin a key interrogation, you are given infinite chances to do so. Yes, you get a game over state if they get away or you fail the interrogation, but the game picks up at the start of the sequence and won’t proceed until you complete that particular part of the investigation. Most of the interrogations are meaningless, and the game proceeds towards the right solution even if you get every single question wrong.

What I wanted to do was present situations where it was possible to have real consequences. If you make an NPC angry, they won’t talk to you any more. Fail to convince them of something, and you won’t get infinite chances. Miss a clue and lose access to a location where that clue is, you’re out of luck investigating that lead.

So, how do you make this fun? There were two simple solutions I felt were important.

The first was making investigations non-linear, so any lead could be followed or completed at any time. This is something both L.A. Noire and Sherlock Holmes do to an extent, and as a standard principle of adventure game design, it’s usually guaranteed to keep the player having fun, especially in an investigation. If you get stuck during one path, an entirely different option is available for you to investigate.

The second was having some choices made in early cases come back to haunt you. Rather than just receiving an angry letter from someone wrongly accused, I felt it would be more interesting to have a reactive world.

For example, if you’re speaking with the leader of a group of writers, and you decide to taunt her, she’ll get upset and throw you out, then refuse to answer the door, which will close off the ability to continue down this path during the first case. However, her group might come up again as a lead in a later case. If you’ve made her upset, she’ll refuse to speak with you, closing off that lead.

If you accuse the wrong suspect in the second case, you might run into her angry husband later while investigating a lead pertinent to that case, and he’ll throw you out of his place of business and deny you that lead...assuming you spoke to him in the previous case so he knows who you are. So there’s a bit of flexibility in exactly how bad you can screw things up. There are also little details like newspaper headlines and stories about the cases you solve changing based on your results.

The most important issue I wanted to overcome was what happened when a dead end was reached. In early adventure games, even up to the mid-90s, there was a design trope which has come to be lovingly named “Dead Man Walking.” This is used to describe a situation in which the player character is not allowed to proceed in the game, usually because they haven’t picked up an item, or have used it incorrectly (for example, being allowed to eat a pie which is needed to solve a puzzle later on) The game won’t let the player backtrack to pick up the item, or allow them to receive the item again, thus creating an unwinnable dead man walking situation. My idea was to take this design trope, but re-purpose it so that while it is possible to get yourself into a dead end situation, it won’t make the game impossible to continue.

As for how to communicate this idea to the player, since Miles hears his dead partner’s voice, Bill acts as the game’s second person narrator, and so it was easy to have him be able to chime in and indicate that all leads are closed off. Reporting back to your police contact then gives you the option to declare the case unsolved, which moves the story along, although failing to solve too many cases will change elements of the story and have a negative effect on Miles’s self-confidence and mental well-being.

As players, we’ve been conditioned to accept that playing a game means we always have to win, and that “winning” means getting everything completely right and being an amazing superhuman. Even though playing as a super detective might be great escapist fantasy for the player, I believe that there’s a real possibility for disconnect between player and player character when the game pushes them to be smarter than you are, and not when you’re on equal footing.

It’s a much more rewarding feeling when YOU solved the case, rather than when Sherlock Holmes wasn’t allowed to fail the case.

Lamplight City will be released later this year. You can wishlist it on Steam currently.

I remember Francisco mentioning in a podcast with Silver Spook that he reads RPG Codex (he should register and start posting).Reddites

Lamplight City is a detective adventure where it's okay to fail

Not every case has to be solved.

The next adventure from Grundislav Games is Lamplight City, a moody Dickensian detective story set in an alternate history where the US never declared independence. I talked to creator Francisco Gonzalez about the process of creating the fictional city of New Bretagne, troubled protagonist Miles Fordham, and how he wants to make a detective game where screwing a case up doesn't mean a game over screen and a reloaded save.

PC Gamer: Who do we play as, and what makes him tick?

Francisco Gonzalez: Miles is a former police detective turned private investigator whose life is coming apart. He feels responsible for the death of his partner, Bill, which made him resign from the police in disgrace. Not only that, he's begun hearing Bill's voice in his head at all hours. Is it Bill's ghost? Is it the guilt making him go crazy? All he knows for sure is that the only way to temporarily silence Bill is to take a sleep medicine. He's desperately trying to find the man who caused Bill's death, hoping it will bring him some closure and get rid of the voice, but he has no leads. All of this has put a strain on his marriage, as his wife senses he's keeping something from her. So all in all, Miles isn't having the best time.

Depending on how the game is played, could one player's version of Miles be different from another?

It's more that Miles's personal story will change, rather than his personality. Miles isn't a complete blank slate, but you can choose to be nice to people, or go the ‘bad cop’ route and be more of a jerk. Where Miles ends up and how his relationships stand will depend on the choices you make throughout the game.

What kind of city is New Bretagne?

It's a mix of all my favorite elements from cities in detective fiction. It's mainly a mix of 19th century New York and New Orleans, with a bit of Victorian London thrown in. I wanted to create my own fictional city and world for this game, since it gave me more creative freedom, rather than picking a specific place and trying to be 100% historically accurate. The city itself is coastal, located on a river in roughly the area of northern Virginia. It's divided into four boroughs, each with its own distinct flavor. There's an influence of French and English culture, and also a large population of immigrants from the West Indies. My hope is that New Bretagne will feel familiar, but also unique enough to seem like a real place.

How has real history informed the creation of the city?

I studied the histories of New York and New Orleans, figuring out who would likely have settled in a city like this. Since the game takes place in an alternate history where the US never declared independence, it was clear that England would still be ruling over the country, so re-imagining the whole of the US as a Commonwealth was also fun. I also have a bit of a steampunk element, although it's not the top hats with goggles and mechanical arms variety. Rather, I wanted to acknowledge that there is an industrial revolution going on, just with technology that's a few decades more advanced, the idea being that since there was no Revolutionary War, scientific research has come further. This also opened up some interesting narrative opportunities to explore in themes like class divides, race issues, etc.

What kind of crimes will we investigate as Miles?

Since he's a private investigator who gets his cases under the table from his only friend in the police department, Miles will be investigating crimes that either the police don't prioritize, or that aren't quite as open and shut as they would imagine. There is, of course, one murder case, but there's also attempted murder and kidnapping. My favorite case involves a woman who mysteriously burns to death in her bed. Miles needs to determine if foul play was involved, or if it was something a bit more out of the ordinary. That one case is as close to the supernatural as the game gets, which is why I had the most fun. Also, it features some of my favorite characters, and a bit where you can be just an absolute jerk in the most twisted way possible.

Is the game an anthology of sorts, or are the cases linked by a larger narrative?

The four main cases are fairly standalone, although they have some thematic links to what Miles is going through. There's also some overlap in the characters you meet, so how you treat a character in an early case might affect a later case if you happen to meet them again. The overarching narrative is Miles's search for Bill's killer, and that is what the final case involves. Before that, however, Miles takes cases because he hopes that by staying involved in solving crimes around New Bretagne, he might find some connection or lead to the killer. Not only that, he needs to keep himself busy so Bill's constant talking doesn't drive him to the insane asylum.

Detective games often suffer from a lack of player agency. What steps are you taking to avoid this?

My biggest issue with detective games is that they often go out of their way to push you towards the right solution. The problem this creates is that more often than not, you as the player feel as though the game is solving the mystery for you, or that the detective you're playing as is smarter than you. So I decided to try making a detective game where it's okay to get things wrong, or to completely fail and not be able to solve a case, but allow the story to continue.

Each case in Lamplight City has multiple suspects and leads to pursue. It's entirely possible to get everything right, accuse the wrong suspect, or screw everything up and reach a dead end. If you do reach a dead end, you simply report to your police contact, declare the case unsolvable, and move on to the next one. The way each case plays out will have an effect on the story, so don't expect to get the best ending if you declare too many cases unsolvable. By allowing you to fail, and letting you discover clues and pursue the leads you think are important, my hope is that you as the player will feel like a detective, rather than just playing as a detective character who isn't allowed to be wrong.

What are the unique challenges of designing a game that reacts to a player's choices?

There are quite a few! Mainly it's trying to tie everything together into a satisfying and cohesive narrative. It's easy to say you want to make a game where it's okay to fail, but you also have to create an enjoyable experience for players who want to go through and play the game getting everything wrong on purpose. If nothing really changes with a different play style, then it's easy to feel cheated, so I wanted to make sure that your choices felt like they mattered. Obviously, I'm a solo indie developer, so I didn't set out to make an impossibly huge epic AAA branching narrative, but I feel that the game has enough variety that it will require at least three playthroughs to see all the content.

You have a history in adventure games. Would you consider this a 'classic' point-and-click game, or are you playing with the genre in any interesting ways?

I've been referring to this as a 'detective game' rather than an 'adventure game', mainly because it focuses more on the actual investigations, clue-finding, and interrogations rather than any sort of inventory-based puzzles. In fact, the game doesn't have a traditional inventory system at all. I took inspiration from Westwood's 1997 Blade Runner adventure game, where you would pick up items at crime scenes, but there were no 'use item on hotspot' type puzzles.

In this game, if you find a tool or item that can help you overcome an obstacle, the cursor will either change automatically to indicate that a new action is available, or interacting with the object will bring up a menu from which you can choose to use said item or tool. My main goal was to avoid going into the realm of the implausible by having puzzles requiring you to collect and combine all sorts of items. That sort of thing is fine in comedies or more traditional point-and-clicks, but in my opinion it has no place in a more serious detective game.

How would you describe the atmosphere?

It's not overly serious, but it does have somewhat of a dark tone. Miles is dealing with some tough issues in his life, as well as investigating some disturbing and sometimes gruesome crimes, so it's not all sunshine and rainbows. That being said, I did want to balance it out with a fair amount of humour, although it's of the more witty and dry variety than zany comedy.

In terms of the visuals and audio, I want players to feel like they've stepped into a John Atkinson Grimshaw painting. His work is so moody and atmospheric, and I wanted to do my best to emulate that in the game's night scenes and general feel. The soundtrack is being composed by Mark Benis, who is doing an amazing job of making the score sound like a lost Hitchcock film. I really believe that this sort of filmic music is rare in adventure games, and really brings the whole thing to life in a unique way. I'm excited for everyone to hear it!

What fiction, in any medium, has influenced you when writing the game and building its world?

Before I came up with "Lamplight City" as the title (which was an extremely difficult process, but that's a whole other story) the game's code name was "Poe-Dickens." I wanted to take the macabre tone of Poe's stories and mix them with the memorable characters and odd names of Dickens's novels. Appropriately enough, Poe is credited as having invented the detective fiction genre, and Dickens's last novel (which he died before completing) was a murder mystery.

I was also deeply inspired by the Dishonored games with regards to world-building, since I admire them for their attention to detail and believability, something I tried my best to emulate. And I would be lying if I said that Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers wasn't a huge influence on the game's aesthetic, particularly the close-up conversations.

Lamplight City hands-onPREVIEW

Written by Richard Hoover — July 13, 2018

Lamplight City

Developer:

Grundislav Games

I was fortunate enough to have the chance to play a preview copy of the upcoming Lamplight Cityby Francisco Gonzalez, creator of previous tales like A Golden Wake and Shardlight with Wadjet Eye. Gonzalez, publishing this time under his own Grundislav Games label, positions this retro-styled 2D point-and-click game with the unique elevator pitch of “a detective game where it’s okay to fail.” I was intrigued. Since most people – and I definitely include myself in this category – aren’t on the intellectual plane of Sherlock Holmes or Hercule Poirot, I wondered if that meant the mysteries would be obvious or if I’d have to pay extra special attention to what was going on in true detective style. Interestingly, the answer is neither, at least in the part I got to sample.

Lamplight City is set in an alternative Victorian era timeline. It takes place in 1844 in the city of New Bretagne, which has more than a passing similarity to New Orleans as represented in Jane Jensen’s Sins of the Fathers. In fact, much of this game seems inspired by the first Gabriel Knight. The map screen for moving from place to place looks very familiar. Dialogs with other characters switch to black screens with detailed, animated portraits and a list of topics to talk about with whomever you’re interviewing. The protagonist wears a long, dark jacket like Gabriel Knight – which is actually joked about in the game. Locations you visit can also be reminiscent of GK, such as the local coffee shop. You even get to ask people what they know about voodoo in a few places.

All this is done rather tongue-in-cheek and is clearly an homage to the Sierra fan favorite, especially as the actual content of the game differs significantly (there’ll be no Schattenjägering here). While Gabriel Knight is clearly the biggest influence on Lamplight City, other subtle nods to golden age classics such as Loom as well as some more recent games like the Blackwell series can also be found.

Visually, the pixel art is what we’ve come to expect from Grundislav. Every scene and character is beautifully and vibrantly drawn, and the animated dialog portraits are wonderfully detailed. In fact, the game steps up the resolution from the studio’s previous 320x200-esque artwork to 640x480 (or its widescreen equivalent). The increased resolution allows for finer detail while still retaining that classic retro look when viewed on today’s larger screens.

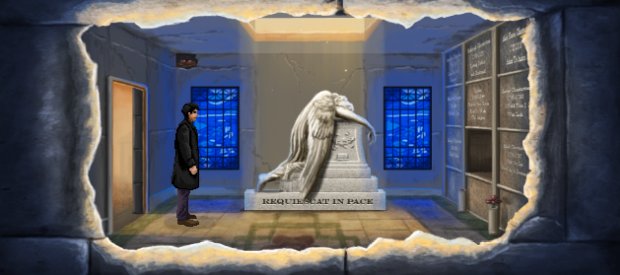

In my travels I visited the run-down areas of New Bretagne at night, which was suitably creepy. I made a trip out to the quiet but melancholic cemetery with its many aboveground mausoleums. And I dropped into residences both opulent and humble as I hobnobbed with the different classes of society. Each location is quite distinct and filled with enough background detail to make them feel real without becoming a cluttered mess. I had no difficulty in determining what areas of the screen could be interacted with, even without having to run the mouse over them to get a pop-up labelling what they were.

The detail isn’t just present when the game is standing still either. All of the characters move fluidly and their range of animation is greater than in many larger scale productions seen in recent years. Whether it’s people climbing through windows, getting into fist fights (don’t worry, you don’t control the fighting), or dead bodies falling out of unexpected places, they’re all smooth and believable. I don’t want to know what was used as reference for the latter.

The story of Lamplight City centers around two detectives, initially working for the New Bretagne police. You control Miles Fordham, the more diligent and serious of the pair. Your partner is Bill Leger, who tags along and offers up the occasional insight, especially when it comes to the city’s societal divisions.

Bill hails from Cholmondeley (pronounced Chumley), a lower class neighborhood colloquially known as “the Chum” that everyone seems to be trying to get out of. In the section that I played, it wasn’t mentioned where Miles came from, but the implication seems to be that he is of higher birth. Apart from the class distinctions between rich and poor, society is also fractured by race and sexual orientation. While the game doesn’t focus on these particular aspects for now, they are always present as an underlying tension and possible motivations for people to commit crimes. In this alternate Victorian world, there is also the increasing pressure of “steamtech”, with modern machines displacing people from their jobs. Although the game is set in the 1800s, it resonates well with issues cropping up frequently in present day news headlines.

Miles and Bill are a crack investigative team as the adventure opens. They’ve been summoned to a flower shop in the Chum where for several weeks a thief of sorts has mysteriously been entering and stealing flowers even though the proprietor swears the store has been securely locked. I say “of sorts” because the thief is considerate enough to leave behind payment for the flowers taken. This scenario serves as a sort of mini-case that introduces the different elements of the interface as well as setting up the larger overarching story for the rest of the game.

Without spoiling anything, this initial investigation does not quite go according to plan. After things fall off the rails, the game fades to black and rejoins Miles and Bill three months later. No longer on the police force, Miles and Bill’s fortunes have taken a turn for the worse – Bill’s in particular, but even Miles is taking nightly soporifics to help him sleep, while also dulling his abilities. Fortunately, a new case is sent their way by an associate still working for the police force. An upper class woman apparently died but the mourners were in for a shock at the funeral when she came to life again and began banging on the coffin. The police presume foul play and have a suspect in custody, but only on the flimsiest of evidence. It’s up to Miles and Bill to investigate to determine who the real culprit is.

Accompanying the press demo was a link to a key blog post about the game’s development. Fair warning, the article does contain a few early game spoilers, which I shall not repeat here. The key takeaway, however, is that this adventure was set up, in theory, to place the onus of solving crimes on the player. The full game will comprise five different cases, with decisions you make early on impacting your later investigations. I was a little apprehensive about how difficult the cases would prove to be. In other storytelling mediums – novels, television shows, movies – we marvel at the detectives who have those brilliant moments of insight that allow them to crack cases and put all the conundrums to rest. It’s hard to replicate that in a game, which is why many mystery adventures take players along an overall linear course that leads them to the right answer whether they’ve made the intuitive jump to get there or not.

The preview only featured the introduction and first case, so I can’t speak for the entirety of the game. However, within the initial main case it’s quite easy to figure out who the real criminal is, as one of the first things they do when you meet them is to confess to the crime. Even so, through your investigation it’s possible to discover the means and motive for another character as well, giving you the option to choose which of the two suspects to accuse. My sense of potentially blowing this decision wasn’t that I might misinterpret evidence and accuse the wrong person while thinking I’d solved the case correctly, but rather that if I really wanted to, I could choose to knowingly accuse the wrong person. A curious approach to the concept of failure indeed. That said, I would assume that the actual criminal doesn’t just confess in every case and that, hopefully, the cases become more challenging as the game progresses.

With the limited scope of what I experienced, I also wasn’t really able to judge the “reactive world” being promised. There were a few places where I could make choices on how to proceed, which mostly just altered one or two lines of dialog, or in a couple of instances removed locations from the map where characters no longer welcomed my presence. Perhaps such choices have more lasting effect later on, but even in solving the first case my decisions didn’t seem to really register. I first named the correct suspect and then reloaded and wrongfully accused another. Miles and Bill had no problem pointing the finger at someone else… using exactly the same lines as when I chose the right criminal. It remains to be seen if the full game will deliver more in its handling of both unintended failure and the consequences of choices.

Decision points aside, the rest of your investigation consists primarily of talking to suspects. Occasionally conversation choices are presented as dialog options at the bottom of the screen. However, most of the time you switch to the detailed character portraits and are given a list of topics to choose from. Subjects are removed from the list once you’ve used them. Every now and then a topic will unlock a new location or add an important detail to your notebook, which is accessed by right-clicking or through a button on a hidden menu bar that displays when you move the mouse to the top of the screen.

This is a dialog-heavy game, and those who appreciate such experiences will enjoy the character and world building that’s nicely woven into the conversations as background detail. With so much dialog, I’d have appreciated the opportunity to save between options, but being able to play a game that otherwise allows free saves anywhere is quite refreshing at a time when more and more adventures are moving towards single-slot checkpoint saves. Besides, it’s easy to leave a conversation between dialog options in order to save before speaking to the suspect again to continue. After all, real life does sometimes intrude on playing games.

Lamplight City eschews inventory puzzles and in fact does not give you access to an inventory at all. You can pick up some items in your investigation but once you have, Miles will automatically use them if appropriate when you click on a relevant hotspot. For example, during the tutorial section you have to determine if a window at the flower shop could have been unlatched from the outside. A hanger from the store is needed to conduct an experiment, which Miles uses without prompting when you click on the window in question. On occasions such as this, you are then typically taken to a close-up view of what you’re interacting with to do more direct manipulation. In this particular instance, you have to carefully drag the hanger around the edges of the window to see if you can unlatch it. Throughout the first case I encountered a small handful of these sequences, which form the only interactions you have other than talking to characters and traveling from place to place.

When interrogating suspects, even the bit characters are all fully voiced, with acting that ranges from acceptable to quite good and nobody delivering a poor performance. I found the interplay between straight-laced Miles and rough-around-the-edges Bill to be especially enjoyable. An attentive ear will pick out some Wadjet Eye voice regulars, which is unsurprising given the developers’ past association.

The rest of the soundscape is filled with other nice touches. Footfall varies with the surface being walked on, such as concrete, wood, or carpet. Birds chirp and pedestrian traffic can be heard in outdoor scenes, while the walla of a crowd can be heard in the coffee shop. The musical score also pleasantly accompanies the investigation, feeling classical but with just a bit of an edge to match the more steampunk elements that have been introduced.

The demo clocked in at half an hour for the intro and three hours for the first case proper. If that’s representative of what to expect throughout, then the full five cases should provide a quite substantial play time indeed. While the lengthy dialogs I encountered did grow a little tiresome, the lush artwork, intriguing world of New Bretagne, and promise of a sizable adventure have definitely caught my interest. In particular I’m looking forward to seeing more fully how the promise of a game where it’s fine to fail and where the world reacts to my decisions plays out, as it’s still too early to tell after just one case. The investigating I’ve done so far has been suitably intriguing, and I'm anxious to see how each of the different cases ultimately ties into the overarching plot that is only thinly hinted here. Fortunately, there isn’t too much longer to wait, as Lamplight City is currently on track for an August release.

Don't wait for Unawoved.FFS, why is everything coming out in August/September?

Gonna save this and Unavowed for my Xmas holidays to get my PnC fix.