RPG Codex Preview: No Truce With The Furies

RPG Codex Preview: No Truce With The Furies

Codex Preview - posted by Infinitron on Fri 3 March 2017, 15:31:59

Tags: Disco Elysium; Helen Hindpere; Kaspar Tamsalu; Robert Kurvitz; ZA/UMOf all the Codex's indie pet projects, ZAUM Studio's No Truce With The Furies is undoubtedly the strangest and most imaginative. In these days when the the commercial viability of such projects is in doubt, strong community relations are more important than ever. Perhaps that's why last month, ZAUM invited esteemed Codex contributor Prime Junta across the Baltic to their headquarters in Tallinn, Estonia for a hands-on impression. And what an impression it made! Here's an excerpt from his writeup:

Read the full article: RPG Codex Preview: No Truce With The Furies

The core gameplay in No Truce is a hybrid of point-and-click adventure and RPG dialogue. There is no pixel-hunting; all interactable objects light up with the tab key, and observations brought up by successful (passive) skill checks show up as little thought bubbles you can click on. However, all interactions more complex than a single-line tooltip happen through the dialogue interface, dubbed the Feld Playback Experiment, itself an in-world mystery. Underneath ticks away a robust and parsimonious system of RPG mechanics: what appears in the dialogue interface is a product of your stats, your skills, your thought inventory, your history tracked in behind-the-scenes counters, and die rolls – subtly but effectively represented by a brief sound effect and animation of a spooling tape. Some checks are passive: a line appears in the Feld if you succeeded in an invisible stat check – for example, a successful Empathy check will have that part of your mind inform you that your interlocutor seems to have a thing going with the person they’re talking about; pass an Esprit de Corps check when you do something particularly stupid, and your partner will have your back. Others are active: you make the roll when picking the choice, with the odds displayed in a tooltip.

A great many of these checks, interactions, and dialogues happen inside your mind. Your skills and stats are talking to you, pointing out things, suggesting things to say, demanding things, making connections, causing thoughts to appear in your thought cabinet. Your reactions to these prompts will determine what kind of cop you will become: behind the scenes, counters are incremented and flags are set. There is a tremendous amount of reactivity to these stats, counters, and flags everywhere: an ashtray may spark a craving for cigarettes or do nothing at all; a successful Visual Calculus check will light up a detail in the crime scene that a less observant cop would have missed. The dialogue tree is a virtual forest, a thicket of nodes with associated thresholds and conditions, changing as you change.

There are two kinds of active checks: white ones you can return to after leveling up a skill, while you only get a single shot at a red one. The twist with those red checks is that the failures are often even more rewarding than the successes, not mechanically or in terms of achieving your aims, but in story and character. My failed checks had me in stitches: a hilariously awkward line, netting me a helpless laugh mixed with pity and a dash of sympathy, or another, which becomes a running joke. Kurvitz isn’t kidding about the “disgrace to the uniform” and “complete failure” thing. That’s what you are, or start out as. It’s up to you and your choices whether, over your adventures in the bad part of the bad part of town, you manage to climb out of it, or fade into the pale as another anonymous hobo, by way of Hobocop. Yes, you can equip a plastic bag to collect beer cans you can turn in for a few pennies in a last-ditch effort to stave off despair and defeat.

You’ll probably not want to carry that bag around all the time, however, and not just because your partner will look down on you with a mixture of embarrassment and pity. That’s because you can only equip items in each of your hands. Equip a bottle of booze and you can take a slug mid-dialogue, giving you a bonus to Physique; smoking a cigarette will boost your Intellect. Other items will have their own specific effects: towards the end of the game, you will be able to dual-wield a pack of smokes and a pistolette, should you be so inclined.

[...] Instead of an ethical alignment system, No Truce with the Furies has a political one, of a sort. You don’t track “Lawful” or “Evil,” you track things like “Fascist,” “Communist,” “Moralist,” or “Liberal.” For example, Kurvitz explains, suppose there is a black girl selling newspapers at a street corner. One of the lines you can say to her is “You’re black,” to which she will reply “Yes.” This by itself does not yet affect your Fascist counter. However, follow it up with “So what kind of music do you people listen to these days?” and it will go up a notch. Keep at it, and fascist thoughts will start appearing in your thought cabinet – an inventory for mental loot – and your brain will start feeding you ever more intensely fascist things to say. People will start to take offense, and to avoid that you might want to try to ignore those thoughts, to act normal, mouthing liberal platitudes to cover up your dark, shriveled soul, gradually turning you into a crypto-Fascist or even shifting your political identity to something more socially acceptable. Or you can embrace your inner blackshirt, rack up those fascist thoughts, and eventually process them into their final, complete, crystallised form: Revacholian Nationhood, giving a massive boost to your Physique stat. Slam down a mouthful of cheap booze on top of that, and you will be a full violent meathead, ready to Jean-Claude Van Damme the biggest, meanest kipt in town right in the face, even as you spiral deeper into alcoholism, delirium, and spite. Fascism and alcohol work well together, Kurvitz explains: Hitler started all his shit in beer halls, so if that’s the way you want to play it, he wants you too to have your moment of glory.

This doesn’t mean No Truce is a game about becoming a Fascist, even though, Kurvitz points out, cops are naturally fascist. You can cultivate and process liberal, or radical feminist, or communist thoughts just as well, and many others besides. The Thought Cabinet is central to the game. Liberals will get their vision quest, and political thoughts are by no means the only ones being tracked or processed: you will change many other aspects of your personality and way of acting, and the world will react to it.

No Truce will no doubt spark a fair number of “but what is a RPG?” threads on a fair number of RPG sites. The design decision to mediate all interactions through the dialogue interface does give it a point-and-click adventure feel; moment to moment, gameplay is reminiscent of, say, Chris Bischoff’s Stasis, as the real meat comes up in the Feld. If games like Mass Effect or The Witchers count as RPGs despite taking gameplay way out into cover shooter or twitch territory, then surely a trip in a different direction is allowed too. The Feld Playback Experiment works: it is enjoyable to interact with, it recreates pen-and-paper mechanics better and more faithfully than most action-oriented systems, and it has the welcome side effect of simplifying the programmers’ and designers’ jobs since they can represent everything as dialogue nodes, adding animations, sounds, and visual effects as necessary and as time and resources permit. Combat through dialogue isn’t without precedent, Kurvitz points out – Planescape: Torment had that bit in the Mortuary where you could break someone’s neck if your Dexterity was high enough, followed by a trip to that game’s mind cabinet if you passed a Wisdom check. Combat through the Feld will let ZA/UM sidestep a lot of the time-consuming polishing, balancing, and tuning that a tactical combat system would need. This isn’t a figurine game: it’s a tabletop RPG with narrated combat, transcribed onto a computer, stats, abilities, die-rolls, and all.

A great many of these checks, interactions, and dialogues happen inside your mind. Your skills and stats are talking to you, pointing out things, suggesting things to say, demanding things, making connections, causing thoughts to appear in your thought cabinet. Your reactions to these prompts will determine what kind of cop you will become: behind the scenes, counters are incremented and flags are set. There is a tremendous amount of reactivity to these stats, counters, and flags everywhere: an ashtray may spark a craving for cigarettes or do nothing at all; a successful Visual Calculus check will light up a detail in the crime scene that a less observant cop would have missed. The dialogue tree is a virtual forest, a thicket of nodes with associated thresholds and conditions, changing as you change.

There are two kinds of active checks: white ones you can return to after leveling up a skill, while you only get a single shot at a red one. The twist with those red checks is that the failures are often even more rewarding than the successes, not mechanically or in terms of achieving your aims, but in story and character. My failed checks had me in stitches: a hilariously awkward line, netting me a helpless laugh mixed with pity and a dash of sympathy, or another, which becomes a running joke. Kurvitz isn’t kidding about the “disgrace to the uniform” and “complete failure” thing. That’s what you are, or start out as. It’s up to you and your choices whether, over your adventures in the bad part of the bad part of town, you manage to climb out of it, or fade into the pale as another anonymous hobo, by way of Hobocop. Yes, you can equip a plastic bag to collect beer cans you can turn in for a few pennies in a last-ditch effort to stave off despair and defeat.

You’ll probably not want to carry that bag around all the time, however, and not just because your partner will look down on you with a mixture of embarrassment and pity. That’s because you can only equip items in each of your hands. Equip a bottle of booze and you can take a slug mid-dialogue, giving you a bonus to Physique; smoking a cigarette will boost your Intellect. Other items will have their own specific effects: towards the end of the game, you will be able to dual-wield a pack of smokes and a pistolette, should you be so inclined.

[...] Instead of an ethical alignment system, No Truce with the Furies has a political one, of a sort. You don’t track “Lawful” or “Evil,” you track things like “Fascist,” “Communist,” “Moralist,” or “Liberal.” For example, Kurvitz explains, suppose there is a black girl selling newspapers at a street corner. One of the lines you can say to her is “You’re black,” to which she will reply “Yes.” This by itself does not yet affect your Fascist counter. However, follow it up with “So what kind of music do you people listen to these days?” and it will go up a notch. Keep at it, and fascist thoughts will start appearing in your thought cabinet – an inventory for mental loot – and your brain will start feeding you ever more intensely fascist things to say. People will start to take offense, and to avoid that you might want to try to ignore those thoughts, to act normal, mouthing liberal platitudes to cover up your dark, shriveled soul, gradually turning you into a crypto-Fascist or even shifting your political identity to something more socially acceptable. Or you can embrace your inner blackshirt, rack up those fascist thoughts, and eventually process them into their final, complete, crystallised form: Revacholian Nationhood, giving a massive boost to your Physique stat. Slam down a mouthful of cheap booze on top of that, and you will be a full violent meathead, ready to Jean-Claude Van Damme the biggest, meanest kipt in town right in the face, even as you spiral deeper into alcoholism, delirium, and spite. Fascism and alcohol work well together, Kurvitz explains: Hitler started all his shit in beer halls, so if that’s the way you want to play it, he wants you too to have your moment of glory.

This doesn’t mean No Truce is a game about becoming a Fascist, even though, Kurvitz points out, cops are naturally fascist. You can cultivate and process liberal, or radical feminist, or communist thoughts just as well, and many others besides. The Thought Cabinet is central to the game. Liberals will get their vision quest, and political thoughts are by no means the only ones being tracked or processed: you will change many other aspects of your personality and way of acting, and the world will react to it.

No Truce will no doubt spark a fair number of “but what is a RPG?” threads on a fair number of RPG sites. The design decision to mediate all interactions through the dialogue interface does give it a point-and-click adventure feel; moment to moment, gameplay is reminiscent of, say, Chris Bischoff’s Stasis, as the real meat comes up in the Feld. If games like Mass Effect or The Witchers count as RPGs despite taking gameplay way out into cover shooter or twitch territory, then surely a trip in a different direction is allowed too. The Feld Playback Experiment works: it is enjoyable to interact with, it recreates pen-and-paper mechanics better and more faithfully than most action-oriented systems, and it has the welcome side effect of simplifying the programmers’ and designers’ jobs since they can represent everything as dialogue nodes, adding animations, sounds, and visual effects as necessary and as time and resources permit. Combat through dialogue isn’t without precedent, Kurvitz points out – Planescape: Torment had that bit in the Mortuary where you could break someone’s neck if your Dexterity was high enough, followed by a trip to that game’s mind cabinet if you passed a Wisdom check. Combat through the Feld will let ZA/UM sidestep a lot of the time-consuming polishing, balancing, and tuning that a tactical combat system would need. This isn’t a figurine game: it’s a tabletop RPG with narrated combat, transcribed onto a computer, stats, abilities, die-rolls, and all.

Read the full article: RPG Codex Preview: No Truce With The Furies

[Preview by Prime Junta]

The line between lunacy and genius is an indistinct one, and strange and wonderful things emerge from those that live on it. Somewhere on that line, in a Northerly port city besieged by fog and the grey nothingness of the pale, a fiercely dedicated group of udarniks toil to bring into the world their vision: a computer role-playing game based on the most advanced role-playing system in the known universe, worldbuilding like Tolkien’s but better, destined for success so great its auteur Robert Kurvitz will buy the Star Wars and Planet of the Apes franchises, merge them, tell the fandom to pick the Jedi ape they want to be now, bitches, and finish his day with the immediate dismantling of the State. All this in time for the centenary of the Great October Revolution.

The Estonian studio ZA/UM has boundless ambition, battling impossible odds with nought but passion, raw talent, and a clarity of vision I haven’t seen in computer games since Chris Avellone in his prime. Their first game, No Truce with the Furies, is in full production, with a staff of twenty-five banging away late into the night in a run-down Neoclassical building in old Tallinn, where Reval melts into Revachol. Somebody’s failed real estate investment, the building’s previous occupants were Zen capitalists, and despite ZA/UM’s de-namastefication program some remnants of the Old Regime remain – a tie-dye, a forlorn Namaste cut into a door in cutesy devanagariesque, the Buddha banished to the corridor as Lenin now keeps a commanding eye on development of dialogue trees.

No Truce is to be just the beginning, too: a first, brief foray into the isolas of a world gradually eaten away by the pale, with the real thing to follow its inevitable triumph. The real thing? The Return. (Of what? The Commune? On investment? Views differ.) That brief foray? Perhaps half of Planescape: Torment, think the Hive plus half the Lower Ward. This is not an indie game, Kurvitz insists, that’s demeaning: this is an AAA game, as lush, as grand, as beautiful as anything else out there, from Mass Effect to Pillars of Eternity, and cooler than any of them. And with better music.

I got to play a half-hour or so of an early pre-alpha build, and while the road ahead is long and hard, this is not just a pipe dream, a pitch, or a tech demo. This is already a game. Moment-to-moment gameplay is fluid, natural, and polished; some scripting lacunae and missing puddle reflections aside, it looked, sounded, and played better and glitched out less than, say, Pillars of Eternity in its first beta build. It looks achingly beautiful, with a tree casting a shadow on a flaking plaster wall, raindrops spotting and darkening the pavement as the weather changes, ice floes undulating on a congealing sea, bringing to life a pastel-toned painting of beautiful decay, rich with texture, form, light, and depth. Ambient sound is already in, and there were snatches of the soundtrack composed and performed for the game by the UK group British Sea Power, ready to out-rock, out-karaoke, and out-disco anyone out there.

Other British musicians are involved as well. SikTh vocalist Mikee Goodman gave the protagonist’s reptilian brain a snarling, grating cockney voice in what has to be one the strongest intros to any RPG since Planescape: Torment (that, by the way, unlike the description of ZA/UM’s ambition above, is my take, not Kurvitz’s). There are no lore-dumps or long-winded expositions here, just pain, loss, and a rude awakening into a dead serious police procedural that has you looking for a song and a mysteriously missing shoe, and then: doing something about the corpse hanging in the tree in the backyard for the last week or so.

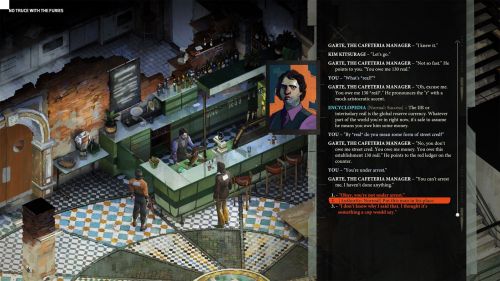

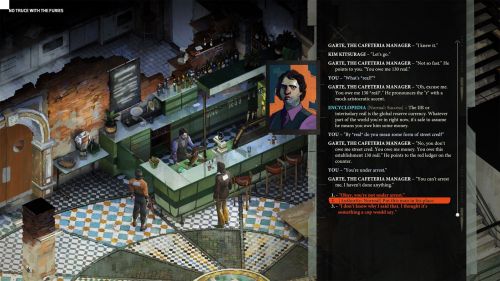

The core gameplay in No Truce is a hybrid of point-and-click adventure and RPG dialogue. There is no pixel-hunting; all interactable objects light up with the tab key, and observations brought up by successful (passive) skill checks show up as little thought bubbles you can click on. However, all interactions more complex than a single-line tooltip happen through the dialogue interface, dubbed the Feld Playback Experiment, itself an in-world mystery. Underneath ticks away a robust and parsimonious system of RPG mechanics: what appears in the dialogue interface is a product of your stats, your skills, your thought inventory, your history tracked in behind-the-scenes counters, and die rolls – subtly but effectively represented by a brief sound effect and animation of a spooling tape. Some checks are passive: a line appears in the Feld if you succeeded in an invisible stat check – for example, a successful Empathy check will have that part of your mind inform you that your interlocutor seems to have a thing going with the person they’re talking about; pass an Esprit de Corps check when you do something particularly stupid, and your partner will have your back. Others are active: you make the roll when picking the choice, with the odds displayed in a tooltip.

Everything, including combat, happens through the dialogue interface. Skill checks are everywhere, and your skills are chatty. Much of the dialogue is internal.

A great many of these checks, interactions, and dialogues happen inside your mind. Your skills and stats are talking to you, pointing out things, suggesting things to say, demanding things, making connections, causing thoughts to appear in your thought cabinet. Your reactions to these prompts will determine what kind of cop you will become: behind the scenes, counters are incremented and flags are set. There is a tremendous amount of reactivity to these stats, counters, and flags everywhere: an ashtray may spark a craving for cigarettes or do nothing at all; a successful Visual Calculus check will light up a detail in the crime scene that a less observant cop would have missed. The dialogue tree is a virtual forest, a thicket of nodes with associated thresholds and conditions, changing as you change.

There are two kinds of active checks: white ones you can return to after leveling up a skill, while you only get a single shot at a red one. The twist with those red checks is that the failures are often even more rewarding than the successes, not mechanically or in terms of achieving your aims, but in story and character. My failed checks had me in stitches: a hilariously awkward line, netting me a helpless laugh mixed with pity and a dash of sympathy, or another, which becomes a running joke. Kurvitz isn’t kidding about the “disgrace to the uniform” and “complete failure” thing. That’s what you are, or start out as. It’s up to you and your choices whether, over your adventures in the bad part of the bad part of town, you manage to climb out of it, or fade into the pale as another anonymous hobo, by way of Hobocop. Yes, you can equip a plastic bag to collect beer cans you can turn in for a few pennies in a last-ditch effort to stave off despair and defeat.

You’ll probably not want to carry that bag around all the time, however, and not just because your partner will look down on you with a mixture of embarrassment and pity. That’s because you can only equip items in each of your hands. Equip a bottle of booze and you can take a slug mid-dialogue, giving you a bonus to Physique; smoking a cigarette will boost your Intellect. Other items will have their own specific effects: towards the end of the game, you will be able to dual-wield a pack of smokes and a pistolette, should you be so inclined.

Yet it is not all unrelenting failure. There is a glimmer of hope in there, somewhere. Your cop brain will notice things. There is a sense that if you stay off the sauce and focus on the task at hand, maybe, just maybe, you will claw your way out of the pit of misery your life has become. This is a dead-earnest police procedural, and while the bit I got to play only sets the scene, there is an external mystery to unravel here too, not just the one building inside your thought cabinet.

The story of ZA/UM began some time in the 1990s, as Estonia dived head-first into the deep end of the liberal-capitalist pool and a bunch of teenagers from Mustamäe dropped out of school to play D&D. That morphed into a Bronze Age world inspired, in part, by Mika Waltari’s The Egyptian, and as the group added elements to their campaign, took them through time from the Perikarnassian through the dark Franconigerian centuries, the Dolorian Renaissance, and ending in a time just at the edge of the Information Age. Tabletop role-playing is not just art, Kurvitz insists, it is the art, richer, deeper, and grander than Wagnerian opera, as he describes the political machinations leading to rare and miraculous elections of the Innocents, individuals invested with absolute political power, or the strange Eastern groupuscule hoping to fend off the end of the world by bringing about full Communism before everything disappears into the never-will-have-been of the pale. Now he wants to turn that artistry into a computer game, to bring some of that grandeur into a more permanent form than an evanescent session of tabletop D&D.

In the interim, Kurvitz and his friends produced a well-received novel set in the same world – Sacred and Terrible Air, currently being translated to English – a film, a band called Ultramelanhool, and a couple of national-level scandals. Now, having learned English from the Internet, they are ready to be let loose on the world at large.

In the Estonian context, naming your thing after an imperial Russian proto-Futurist-Slavic-nationalist-mysticist movement associated with the likes of Velimir Khlebnikov, Aleksei Kruchenykh, and Kasimir Malevich is, to put it mildly, provocative, not to mention just a little arrogant. ZA/UM are not afraid of offending people: liberals, Fascists, Finns with their joke language and backwoods nationalism. They are overtly political: the problem with games and sci-fi these days, Kurvitz says, isn’t that they’re infected by politics, it’s that they’re infected by bad politics. ZA/UM come bearing a good political message: of the emancipatory power and promise of sobriety and hard work, and the light of hope that shines even in the darkest of times. It is not a “grey” game, Kurvitz says; he hates “grey,” No Truce is a beautiful and ultimately bright game.

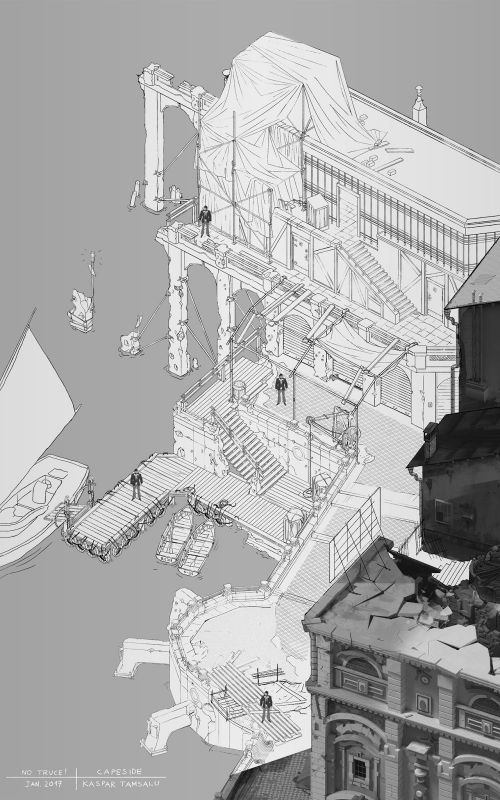

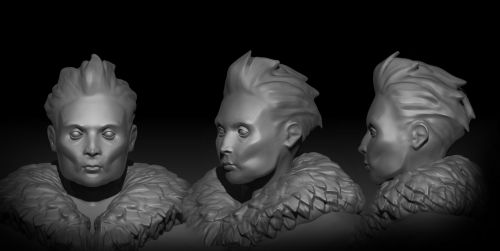

Top: Kaspar Tamsalu, Concept Artist and 3D Modeller (painting by Aleksander Rostov, Art Director). Bottom, front to back: Mikk Luige, Coder/Feature Implementation, Jaagup Irve, Developer.

Instead of an ethical alignment system, No Truce with the Furies has a political one, of a sort. You don’t track “Lawful” or “Evil,” you track things like “Fascist,” “Communist,” “Moralist,” or “Liberal.” For example, Kurvitz explains, suppose there is a black girl selling newspapers at a street corner. One of the lines you can say to her is “You’re black,” to which she will reply “Yes.” This by itself does not yet affect your Fascist counter. However, follow it up with “So what kind of music do you people listen to these days?” and it will go up a notch. Keep at it, and fascist thoughts will start appearing in your thought cabinet – an inventory for mental loot – and your brain will start feeding you ever more intensely fascist things to say. People will start to take offense, and to avoid that you might want to try to ignore those thoughts, to act normal, mouthing liberal platitudes to cover up your dark, shriveled soul, gradually turning you into a crypto-Fascist or even shifting your political identity to something more socially acceptable. Or you can embrace your inner blackshirt, rack up those fascist thoughts, and eventually process them into their final, complete, crystallised form: Revacholian Nationhood, giving a massive boost to your Physique stat. Slam down a mouthful of cheap booze on top of that, and you will be a full violent meathead, ready to Jean-Claude Van Damme the biggest, meanest kipt in town right in the face, even as you spiral deeper into alcoholism, delirium, and spite. Fascism and alcohol work well together, Kurvitz explains: Hitler started all his shit in beer halls, so if that’s the way you want to play it, he wants you too to have your moment of glory.

This doesn’t mean No Truce is a game about becoming a Fascist, even though, Kurvitz points out, cops are naturally fascist. You can cultivate and process liberal, or radical feminist, or communist thoughts just as well, and many others besides. The Thought Cabinet is central to the game. Liberals will get their vision quest, and political thoughts are by no means the only ones being tracked or processed: you will change many other aspects of your personality and way of acting, and the world will react to it.

No Truce will no doubt spark a fair number of “but what is a RPG?” threads on a fair number of RPG sites. The design decision to mediate all interactions through the dialogue interface does give it a point-and-click adventure feel; moment to moment, gameplay is reminiscent of, say, Chris Bischoff’s Stasis, as the real meat comes up in the Feld. If games like Mass Effect or The Witchers count as RPGs despite taking gameplay way out into cover shooter or twitch territory, then surely a trip in a different direction is allowed too. The Feld Playback Experiment works: it is enjoyable to interact with, it recreates pen-and-paper mechanics better and more faithfully than most action-oriented systems, and it has the welcome side effect of simplifying the programmers’ and designers’ jobs since they can represent everything as dialogue nodes, adding animations, sounds, and visual effects as necessary and as time and resources permit. Combat through dialogue isn’t without precedent, Kurvitz points out – Planescape: Torment had that bit in the Mortuary where you could break someone’s neck if your Dexterity was high enough, followed by a trip to that game’s mind cabinet if you passed a Wisdom check. Combat through the Feld will let ZA/UM sidestep a lot of the time-consuming polishing, balancing, and tuning that a tactical combat system would need. This isn’t a figurine game: it’s a tabletop RPG with narrated combat, transcribed onto a computer, stats, abilities, die-rolls, and all.

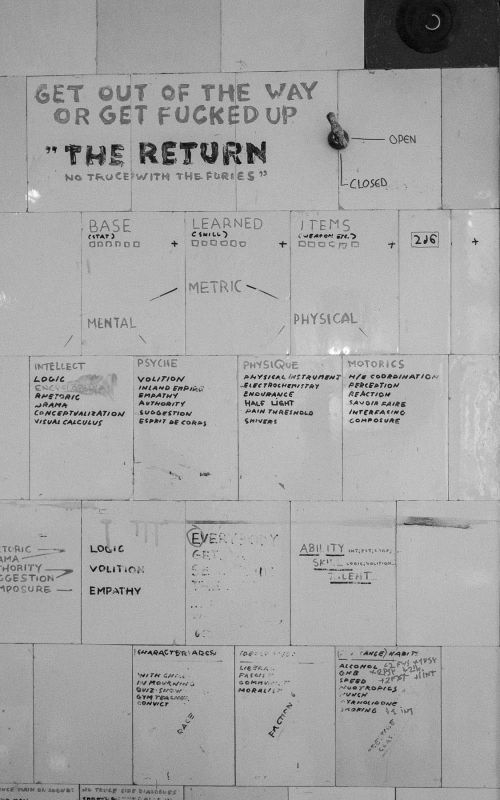

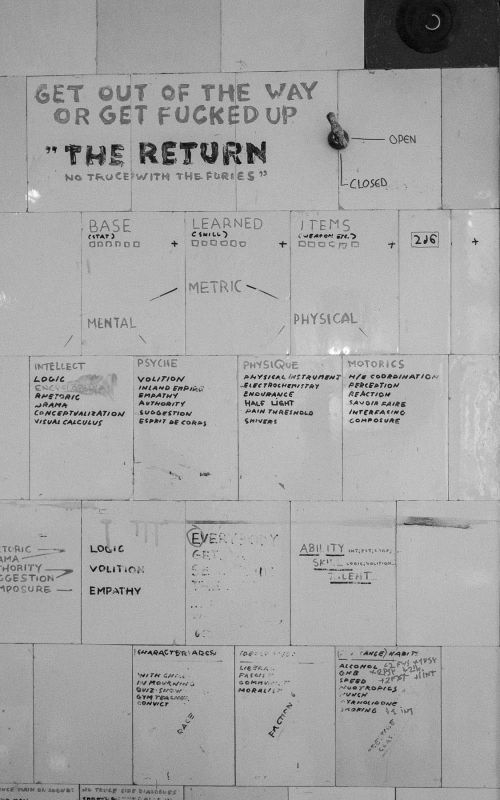

No Truce uses an in-house role-playing system based on a long-running tabletop campaign. Below, Robert Kurvitz.

Robert Kurvitz is a legit literary genius. He has a marvelous facility and inventiveness with language, bending and twisting it to express wild ideas, making up words that conjure associations beyond their primary meanings, twisting others into forms which are at the same time familiar but different, in writing or in a non-stop flow of free association talk, leaping from what BioWare does wrong (and right!) to life in an evaporating linguistic puddle, from that to his massive admiration and professional respect for the mighty Chris Avellone, to cool-headed analysis of the ways Planescape: Torment pushes the envelope of game design – no doubt something that has served him well in his years of dungeon mastering. Revachol does not have cars, it has motor-carriages; dance music is called anodic music, and there are no aircraft plying the skies, but aerostats. This strange but familiar world needs a strange but familiar idiom, which makes an outsider’s take on English an asset rather than a handicap. The dialogue in No Truce flows, leaps, twists, and turns, surprises, delights, and touches. It is fresh and earnest without a hint of weary, ironic detachment; witty, punchy, moving, and inventive. Pretentious? Only if your definition of pretentious includes everything that aspires to something more than light escapist entertainment. After my dip into the game, I was feeling for its pitiable, terminally alcoholic failure of a protagonist. I will save him from the Furies, or die in a gutter trying.

No Truce with the Furies is not some piece of forgettable East European shovelware. It is a work of art in progress, by a movement, of writers, musicians, artists, and programmers, at the same time madly ambitious and wildly sprawling, and invested with tight, coherent systems, an equally tight, coherent aesthetic vision, and an elegant and parsimonious core interaction design that just might suffice to keep the wild outgrowths of its dialogue trees within the realm of the achievable. Disco dancing on the ragged edge between madness and sanity, the possible and the impossible, it is at once a re-invention and a return to the roots of the genre. ZA/UM has a manic energy, boundless ambition, and precious little experience bringing a software project to completion before the creditors close in. No Truce deserves to be completed to the fullest extent of their vision. It has to be completed before the pale of late capitalism engulfs it in its grey never-will-have-been. If it ever is completed, even as a barely-playable bug-ridden mess in the vein of Troika in its prime, it will be a truer spiritual successor to Planescape: Torment than any game advertised as such, a moment of beautiful lunacy hearkening to simpler days when people were able and willing to take real creative risks. I want to, nay, dare to believe.

The Stakhanovite zeal of ZA/UM is certain to bring us No Truce with the Furies before the centenary year of the Great October Revolution is out.

Screenshots and concept art courtesy of ZA/UM. Photos and text by Prime Junta.

The line between lunacy and genius is an indistinct one, and strange and wonderful things emerge from those that live on it. Somewhere on that line, in a Northerly port city besieged by fog and the grey nothingness of the pale, a fiercely dedicated group of udarniks toil to bring into the world their vision: a computer role-playing game based on the most advanced role-playing system in the known universe, worldbuilding like Tolkien’s but better, destined for success so great its auteur Robert Kurvitz will buy the Star Wars and Planet of the Apes franchises, merge them, tell the fandom to pick the Jedi ape they want to be now, bitches, and finish his day with the immediate dismantling of the State. All this in time for the centenary of the Great October Revolution.

The Estonian studio ZA/UM has boundless ambition, battling impossible odds with nought but passion, raw talent, and a clarity of vision I haven’t seen in computer games since Chris Avellone in his prime. Their first game, No Truce with the Furies, is in full production, with a staff of twenty-five banging away late into the night in a run-down Neoclassical building in old Tallinn, where Reval melts into Revachol. Somebody’s failed real estate investment, the building’s previous occupants were Zen capitalists, and despite ZA/UM’s de-namastefication program some remnants of the Old Regime remain – a tie-dye, a forlorn Namaste cut into a door in cutesy devanagariesque, the Buddha banished to the corridor as Lenin now keeps a commanding eye on development of dialogue trees.

No Truce is to be just the beginning, too: a first, brief foray into the isolas of a world gradually eaten away by the pale, with the real thing to follow its inevitable triumph. The real thing? The Return. (Of what? The Commune? On investment? Views differ.) That brief foray? Perhaps half of Planescape: Torment, think the Hive plus half the Lower Ward. This is not an indie game, Kurvitz insists, that’s demeaning: this is an AAA game, as lush, as grand, as beautiful as anything else out there, from Mass Effect to Pillars of Eternity, and cooler than any of them. And with better music.

I got to play a half-hour or so of an early pre-alpha build, and while the road ahead is long and hard, this is not just a pipe dream, a pitch, or a tech demo. This is already a game. Moment-to-moment gameplay is fluid, natural, and polished; some scripting lacunae and missing puddle reflections aside, it looked, sounded, and played better and glitched out less than, say, Pillars of Eternity in its first beta build. It looks achingly beautiful, with a tree casting a shadow on a flaking plaster wall, raindrops spotting and darkening the pavement as the weather changes, ice floes undulating on a congealing sea, bringing to life a pastel-toned painting of beautiful decay, rich with texture, form, light, and depth. Ambient sound is already in, and there were snatches of the soundtrack composed and performed for the game by the UK group British Sea Power, ready to out-rock, out-karaoke, and out-disco anyone out there.

Other British musicians are involved as well. SikTh vocalist Mikee Goodman gave the protagonist’s reptilian brain a snarling, grating cockney voice in what has to be one the strongest intros to any RPG since Planescape: Torment (that, by the way, unlike the description of ZA/UM’s ambition above, is my take, not Kurvitz’s). There are no lore-dumps or long-winded expositions here, just pain, loss, and a rude awakening into a dead serious police procedural that has you looking for a song and a mysteriously missing shoe, and then: doing something about the corpse hanging in the tree in the backyard for the last week or so.

The core gameplay in No Truce is a hybrid of point-and-click adventure and RPG dialogue. There is no pixel-hunting; all interactable objects light up with the tab key, and observations brought up by successful (passive) skill checks show up as little thought bubbles you can click on. However, all interactions more complex than a single-line tooltip happen through the dialogue interface, dubbed the Feld Playback Experiment, itself an in-world mystery. Underneath ticks away a robust and parsimonious system of RPG mechanics: what appears in the dialogue interface is a product of your stats, your skills, your thought inventory, your history tracked in behind-the-scenes counters, and die rolls – subtly but effectively represented by a brief sound effect and animation of a spooling tape. Some checks are passive: a line appears in the Feld if you succeeded in an invisible stat check – for example, a successful Empathy check will have that part of your mind inform you that your interlocutor seems to have a thing going with the person they’re talking about; pass an Esprit de Corps check when you do something particularly stupid, and your partner will have your back. Others are active: you make the roll when picking the choice, with the odds displayed in a tooltip.

Everything, including combat, happens through the dialogue interface. Skill checks are everywhere, and your skills are chatty. Much of the dialogue is internal.

A great many of these checks, interactions, and dialogues happen inside your mind. Your skills and stats are talking to you, pointing out things, suggesting things to say, demanding things, making connections, causing thoughts to appear in your thought cabinet. Your reactions to these prompts will determine what kind of cop you will become: behind the scenes, counters are incremented and flags are set. There is a tremendous amount of reactivity to these stats, counters, and flags everywhere: an ashtray may spark a craving for cigarettes or do nothing at all; a successful Visual Calculus check will light up a detail in the crime scene that a less observant cop would have missed. The dialogue tree is a virtual forest, a thicket of nodes with associated thresholds and conditions, changing as you change.

There are two kinds of active checks: white ones you can return to after leveling up a skill, while you only get a single shot at a red one. The twist with those red checks is that the failures are often even more rewarding than the successes, not mechanically or in terms of achieving your aims, but in story and character. My failed checks had me in stitches: a hilariously awkward line, netting me a helpless laugh mixed with pity and a dash of sympathy, or another, which becomes a running joke. Kurvitz isn’t kidding about the “disgrace to the uniform” and “complete failure” thing. That’s what you are, or start out as. It’s up to you and your choices whether, over your adventures in the bad part of the bad part of town, you manage to climb out of it, or fade into the pale as another anonymous hobo, by way of Hobocop. Yes, you can equip a plastic bag to collect beer cans you can turn in for a few pennies in a last-ditch effort to stave off despair and defeat.

You’ll probably not want to carry that bag around all the time, however, and not just because your partner will look down on you with a mixture of embarrassment and pity. That’s because you can only equip items in each of your hands. Equip a bottle of booze and you can take a slug mid-dialogue, giving you a bonus to Physique; smoking a cigarette will boost your Intellect. Other items will have their own specific effects: towards the end of the game, you will be able to dual-wield a pack of smokes and a pistolette, should you be so inclined.

Yet it is not all unrelenting failure. There is a glimmer of hope in there, somewhere. Your cop brain will notice things. There is a sense that if you stay off the sauce and focus on the task at hand, maybe, just maybe, you will claw your way out of the pit of misery your life has become. This is a dead-earnest police procedural, and while the bit I got to play only sets the scene, there is an external mystery to unravel here too, not just the one building inside your thought cabinet.

The story of ZA/UM began some time in the 1990s, as Estonia dived head-first into the deep end of the liberal-capitalist pool and a bunch of teenagers from Mustamäe dropped out of school to play D&D. That morphed into a Bronze Age world inspired, in part, by Mika Waltari’s The Egyptian, and as the group added elements to their campaign, took them through time from the Perikarnassian through the dark Franconigerian centuries, the Dolorian Renaissance, and ending in a time just at the edge of the Information Age. Tabletop role-playing is not just art, Kurvitz insists, it is the art, richer, deeper, and grander than Wagnerian opera, as he describes the political machinations leading to rare and miraculous elections of the Innocents, individuals invested with absolute political power, or the strange Eastern groupuscule hoping to fend off the end of the world by bringing about full Communism before everything disappears into the never-will-have-been of the pale. Now he wants to turn that artistry into a computer game, to bring some of that grandeur into a more permanent form than an evanescent session of tabletop D&D.

In the interim, Kurvitz and his friends produced a well-received novel set in the same world – Sacred and Terrible Air, currently being translated to English – a film, a band called Ultramelanhool, and a couple of national-level scandals. Now, having learned English from the Internet, they are ready to be let loose on the world at large.

In the Estonian context, naming your thing after an imperial Russian proto-Futurist-Slavic-nationalist-mysticist movement associated with the likes of Velimir Khlebnikov, Aleksei Kruchenykh, and Kasimir Malevich is, to put it mildly, provocative, not to mention just a little arrogant. ZA/UM are not afraid of offending people: liberals, Fascists, Finns with their joke language and backwoods nationalism. They are overtly political: the problem with games and sci-fi these days, Kurvitz says, isn’t that they’re infected by politics, it’s that they’re infected by bad politics. ZA/UM come bearing a good political message: of the emancipatory power and promise of sobriety and hard work, and the light of hope that shines even in the darkest of times. It is not a “grey” game, Kurvitz says; he hates “grey,” No Truce is a beautiful and ultimately bright game.

Top: Kaspar Tamsalu, Concept Artist and 3D Modeller (painting by Aleksander Rostov, Art Director). Bottom, front to back: Mikk Luige, Coder/Feature Implementation, Jaagup Irve, Developer.

Instead of an ethical alignment system, No Truce with the Furies has a political one, of a sort. You don’t track “Lawful” or “Evil,” you track things like “Fascist,” “Communist,” “Moralist,” or “Liberal.” For example, Kurvitz explains, suppose there is a black girl selling newspapers at a street corner. One of the lines you can say to her is “You’re black,” to which she will reply “Yes.” This by itself does not yet affect your Fascist counter. However, follow it up with “So what kind of music do you people listen to these days?” and it will go up a notch. Keep at it, and fascist thoughts will start appearing in your thought cabinet – an inventory for mental loot – and your brain will start feeding you ever more intensely fascist things to say. People will start to take offense, and to avoid that you might want to try to ignore those thoughts, to act normal, mouthing liberal platitudes to cover up your dark, shriveled soul, gradually turning you into a crypto-Fascist or even shifting your political identity to something more socially acceptable. Or you can embrace your inner blackshirt, rack up those fascist thoughts, and eventually process them into their final, complete, crystallised form: Revacholian Nationhood, giving a massive boost to your Physique stat. Slam down a mouthful of cheap booze on top of that, and you will be a full violent meathead, ready to Jean-Claude Van Damme the biggest, meanest kipt in town right in the face, even as you spiral deeper into alcoholism, delirium, and spite. Fascism and alcohol work well together, Kurvitz explains: Hitler started all his shit in beer halls, so if that’s the way you want to play it, he wants you too to have your moment of glory.

This doesn’t mean No Truce is a game about becoming a Fascist, even though, Kurvitz points out, cops are naturally fascist. You can cultivate and process liberal, or radical feminist, or communist thoughts just as well, and many others besides. The Thought Cabinet is central to the game. Liberals will get their vision quest, and political thoughts are by no means the only ones being tracked or processed: you will change many other aspects of your personality and way of acting, and the world will react to it.

No Truce will no doubt spark a fair number of “but what is a RPG?” threads on a fair number of RPG sites. The design decision to mediate all interactions through the dialogue interface does give it a point-and-click adventure feel; moment to moment, gameplay is reminiscent of, say, Chris Bischoff’s Stasis, as the real meat comes up in the Feld. If games like Mass Effect or The Witchers count as RPGs despite taking gameplay way out into cover shooter or twitch territory, then surely a trip in a different direction is allowed too. The Feld Playback Experiment works: it is enjoyable to interact with, it recreates pen-and-paper mechanics better and more faithfully than most action-oriented systems, and it has the welcome side effect of simplifying the programmers’ and designers’ jobs since they can represent everything as dialogue nodes, adding animations, sounds, and visual effects as necessary and as time and resources permit. Combat through dialogue isn’t without precedent, Kurvitz points out – Planescape: Torment had that bit in the Mortuary where you could break someone’s neck if your Dexterity was high enough, followed by a trip to that game’s mind cabinet if you passed a Wisdom check. Combat through the Feld will let ZA/UM sidestep a lot of the time-consuming polishing, balancing, and tuning that a tactical combat system would need. This isn’t a figurine game: it’s a tabletop RPG with narrated combat, transcribed onto a computer, stats, abilities, die-rolls, and all.

No Truce uses an in-house role-playing system based on a long-running tabletop campaign. Below, Robert Kurvitz.

Robert Kurvitz is a legit literary genius. He has a marvelous facility and inventiveness with language, bending and twisting it to express wild ideas, making up words that conjure associations beyond their primary meanings, twisting others into forms which are at the same time familiar but different, in writing or in a non-stop flow of free association talk, leaping from what BioWare does wrong (and right!) to life in an evaporating linguistic puddle, from that to his massive admiration and professional respect for the mighty Chris Avellone, to cool-headed analysis of the ways Planescape: Torment pushes the envelope of game design – no doubt something that has served him well in his years of dungeon mastering. Revachol does not have cars, it has motor-carriages; dance music is called anodic music, and there are no aircraft plying the skies, but aerostats. This strange but familiar world needs a strange but familiar idiom, which makes an outsider’s take on English an asset rather than a handicap. The dialogue in No Truce flows, leaps, twists, and turns, surprises, delights, and touches. It is fresh and earnest without a hint of weary, ironic detachment; witty, punchy, moving, and inventive. Pretentious? Only if your definition of pretentious includes everything that aspires to something more than light escapist entertainment. After my dip into the game, I was feeling for its pitiable, terminally alcoholic failure of a protagonist. I will save him from the Furies, or die in a gutter trying.

No Truce with the Furies is not some piece of forgettable East European shovelware. It is a work of art in progress, by a movement, of writers, musicians, artists, and programmers, at the same time madly ambitious and wildly sprawling, and invested with tight, coherent systems, an equally tight, coherent aesthetic vision, and an elegant and parsimonious core interaction design that just might suffice to keep the wild outgrowths of its dialogue trees within the realm of the achievable. Disco dancing on the ragged edge between madness and sanity, the possible and the impossible, it is at once a re-invention and a return to the roots of the genre. ZA/UM has a manic energy, boundless ambition, and precious little experience bringing a software project to completion before the creditors close in. No Truce deserves to be completed to the fullest extent of their vision. It has to be completed before the pale of late capitalism engulfs it in its grey never-will-have-been. If it ever is completed, even as a barely-playable bug-ridden mess in the vein of Troika in its prime, it will be a truer spiritual successor to Planescape: Torment than any game advertised as such, a moment of beautiful lunacy hearkening to simpler days when people were able and willing to take real creative risks. I want to, nay, dare to believe.

The Stakhanovite zeal of ZA/UM is certain to bring us No Truce with the Furies before the centenary year of the Great October Revolution is out.

Screenshots and concept art courtesy of ZA/UM. Photos and text by Prime Junta.

There are 334 comments on RPG Codex Preview: No Truce With The Furies