Last week I was thinking about great dungeons in RPGs and made the terrible mistake of checking reddit, where people were praising Oblivion's Sundercliff Watch, a "mega-dungeon" that was sold as a separate DLC.

In my second mistake, I reinstalled Oblivion and went to check it out.

It was so shitty that I wrote a 3,000 words rant on why it sucks so much, which then became a 3,000 words article on what makes a good CRPG dungeon.

You can read it here: https://medium.com/@felipepepe/what-makes-a-good-rpg-dungeon-505180c69d00

Or here:

Would be curious in hearing the Codex's thoughts, especially of Melan , which I cited

In my second mistake, I reinstalled Oblivion and went to check it out.

It was so shitty that I wrote a 3,000 words rant on why it sucks so much, which then became a 3,000 words article on what makes a good CRPG dungeon.

You can read it here: https://medium.com/@felipepepe/what-makes-a-good-rpg-dungeon-505180c69d00

Or here:

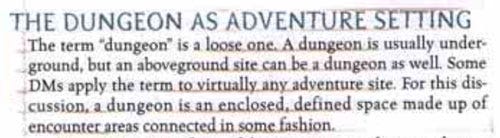

First of all, what is a dungeon?

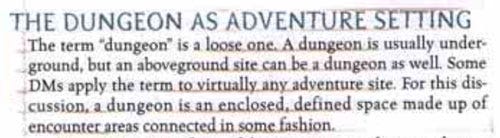

I don’t want to dwell much on this, so I’ll just use D&D’s definition from the 3rd Edition Dungeon Master Guide:

I like that, and it works well for both tabletop RPGs and computer & console RPGs (which I’ll hereby just call “CRPGs”). But what’s a good dungeon?

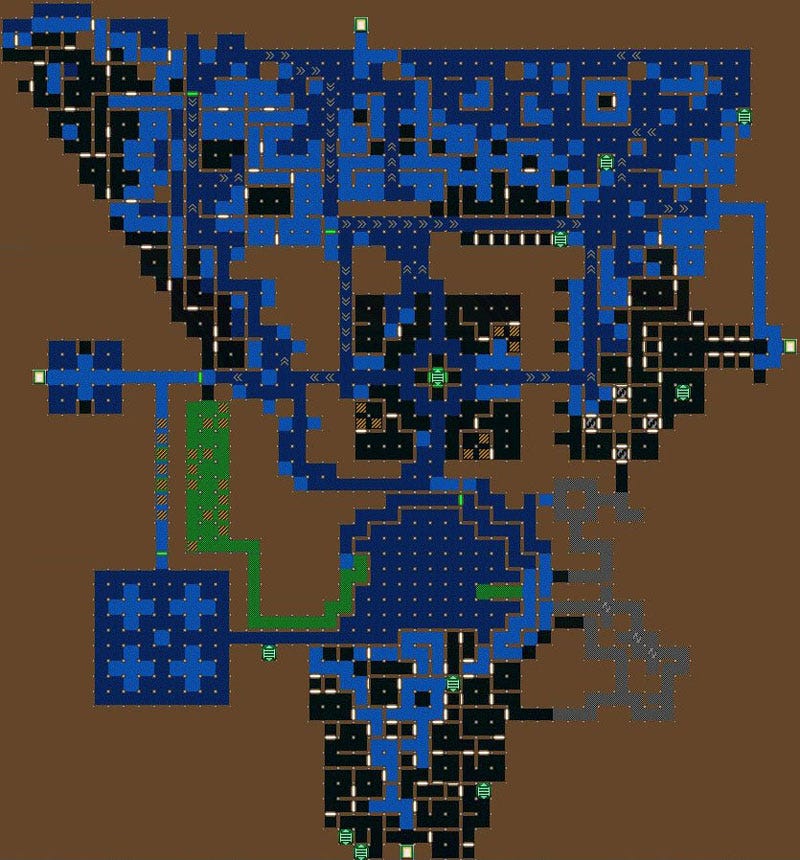

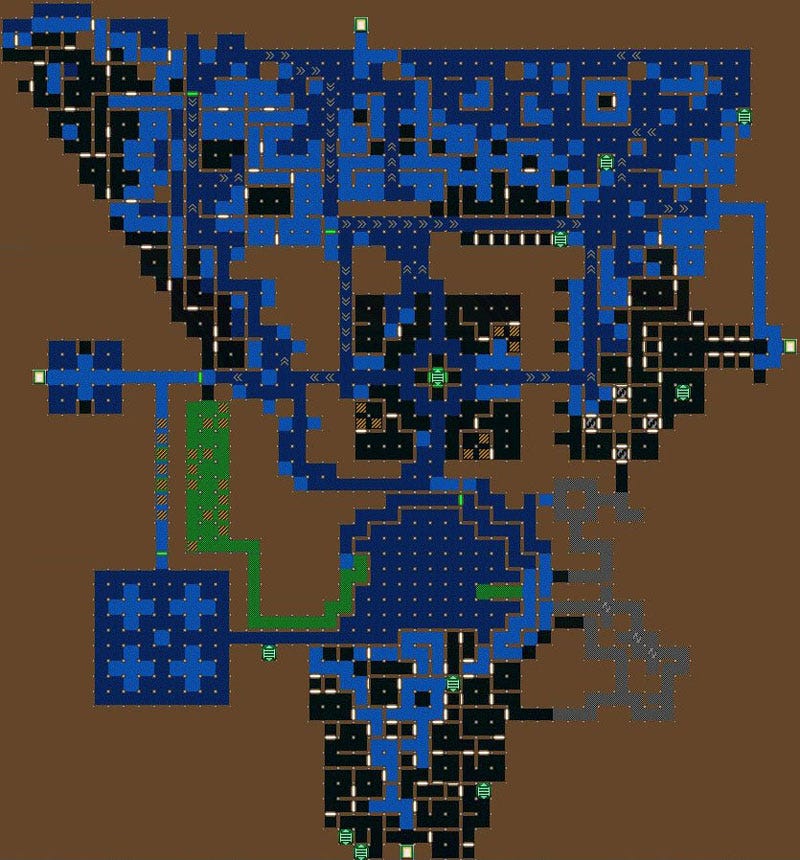

It may sound obvious, but a good dungeon in a CRPG must fit its game. For example, I enjoy the massive spaghetti-from-hell dungeons of Daggerfall:

(image captured via "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">Daggerfall Modelling)

They work because in Daggerfall you move fast, there are movement skills like flying, climbing, swimming and teleporting (thank god for teleport), combat encounters are rare & solved quickly and the first-person camera makes crossing the maze feel very satisfying, in a classic Doom kind of way.

If you used this design on Final Fantasy IX, with its slow movement, slow turn-based combat, constant random encounters and fixed camera, it would be unbearable. The same applies if you had to explore it stuck to a grid, as in Legend of Grimrock, or dragging a large party around, as in Baldur’s Gate.

Similarly, Demon’s Souls Tower of Latria is an amazing dungeon but it would probably suck in tabletop or even in an isometric CRPG, as so much of what makes it so great is tied to directly maneuvering your hero across 3D space.

Again, it sounds obvious, but think how different from tabletop RPGs that is.

There’s an entire industry of indie publishing houses making award-winning “system-agnostic” dungeons and campaigns that you can play using almost any RPG ruleset, from D&D to GURPS, Warhammer, Call of Cthulhu, Shadowrun or even Toon.

Meanwhile, just imagine playing a dungeon from AssAssCreed: Odyssey as Mass Effect’s Shepard, who can’t even jump. Mass Effect simply doesn’t offer the tools to explore Odyssey’s world. And there’s no DM to go “uh… just roll a d20 and try to get 14 or more”, all that the Mass Effect toolbox would allow is for you to press A and see a cutscene of Shepard climbing. How dull.

So CRPG dungeon design is intrinsically tied to the “verbs” that are available to the player — if can he jump, climb, sneak, fly, teleport, swim, fight ranged enemies, lockpick, break objects, directly maneuver with objects, talk to NPCs, push objects, etc.

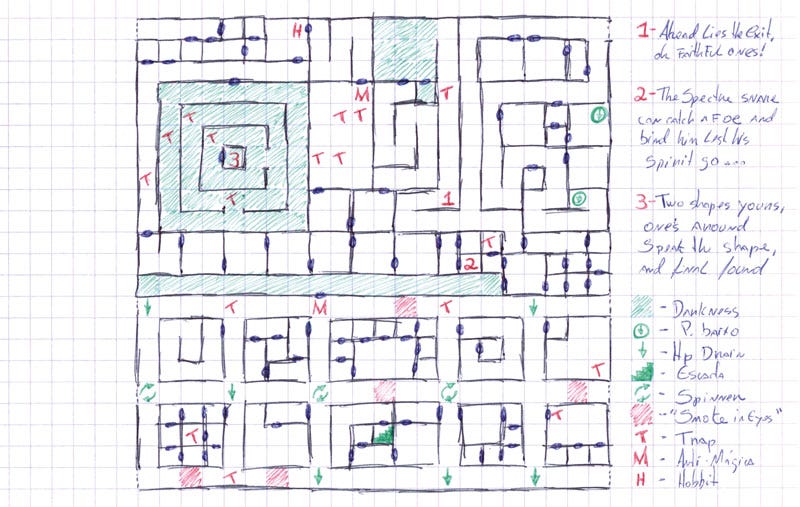

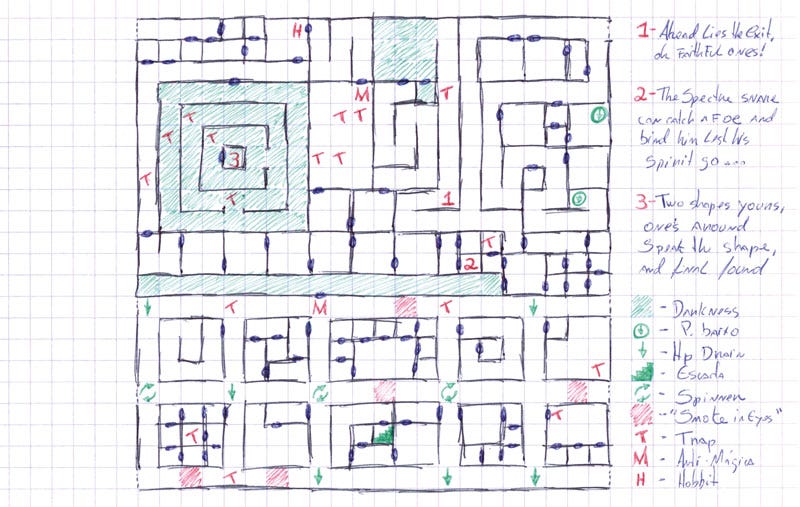

Obviously the perspective, combat style, party size and skills also affect the dungeon design, but even things like the UI can radically alter how a dungeon is designed. For example, back in the 80s CRPGs didn’t have in-game maps, so you were expected to draw your own maps on paper — some CRPGs even included graph paper inside the game box.

Since the designers knew players were mapping every step, it was common to have traps that would spin or teleport the player away — without any warning! By the time you figured it out you weren’t where you expected to be, you had to erase half of your map and try to find where it went wrong.

This was a traditional challenge in most 80s CRPGs, like Wizardry, Might & Magic, Dungeon Master, Bard’s Tale and the Gold Box series, all of which were first-person RPGs. But this sort of challenge doesn’t work in isometric or third-person RPGs, and it vanished once in-game maps became a thing.

Think about that: a change in UI drastically changed how dungeons were designed and played in CRPGs!

So, while there are many resources on dungeon design for tabletop RPGs, such as "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">JohnnFour’s 5 Room Dungeon, "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">Kent David Kelly’s trilogy of books or "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">this cool article on dungeon maps, it’s much harder to do something like that for CRPGs. If you are making a first-person RPG, then "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">Luke McMillan’s article on FPS line of sight can be as useful than any tabletop reference, but the same article would be almost useless when designing an isometric RPG.

Therefore, what we’ll do for the remaining of this article is take a look at some really great dungeons and try to see what makes them so great, hopefully learning something in the progress.

So here’s my personal selection of some amazing dungeons:

Shurugeon Castle (Wizards & Warriors)

As you enter this haunted castle, the ghost of knight D’Soto appears and tells you a demon took over the castle. The demon is in the throne room, which you can easily reach, but he’s immortal, immune to your attacks.

As you explore the castle for clues, a narrator describes the most important areas and set pieces, while the demon constantly taunts you and sends his minions to ambush you. Soon you find D’Soto’s squire, who fights alongside you and tells that he found a way to kill the demon by collecting 5 items and performing a ritual. He gives you one of the items, the other 4 must be found by fighting an undead guard, solving a puzzle, uncovering a hidden path and bartering/stealing/killing a vampire — all the game’s main interaction “verbs”.

It’s a classic and “gamey” dungeon design, but it’s extremely well-executed and also makes full use of the “video gamey” part — the dungeon is interconnected and feels like a real place, while also being very “tactile”, requiring you to swim across the moat, lower the draw-bridge, flip switches, ride elevators, jump down from the roof, use items to open secret doors and other interactions that feel great with the game’s FPS-like view and controls.

Of all the dungeons in this list, Shurugeon Castle is the most “generic”. I placed it first because I think that makes it an excellent showcase of great dungeon design without relying on excellent writers, creative concepts or very particular game mechanics.

Sen’s Fortress (Dark Souls)

Dark Souls’ level design is legendary, and Sen’s Fortress is its most iconic dungeon. A lot was written about it already, I just want to add one thing: I think it’s the best use of 3D movement in any RPG ever.

Sure, the layout, the enemies and the secrets are all cool, but the core of the dungeon is fighting and maneuvering your character while avoiding traps, falls and attacks that might push you over.

Clever use of 3D movement is something criminally underused in RPGs, despite the shift towards third-person cameras and heavy action focus, as their controls are usually very floaty and falling to your death is frustrating. Remember how Mass Effect: Andromeda gave you a jetpack, but only offered simple platforming sections that instantly rescued you if you fell down.

Sen’s Fortress demands carefully positioning & maneuvering, and not only for exploration, but as vital part of the dungeon’s combat.

Level 1 (Ultima Underworld)

It’s honestly mind-blowing how UU not only invented 3D RPGs and immersive sims back in 1992, but also did it so goddamn well. It’s very first level has diverse combat encounters, platforming, logic puzzles, keys to be found, levers to be pulled, a river with strong current to swim across, secret areas, lore bits and hints about future challenges, two different paths to the next level and also several inhabitants you can talk to — including two warring factions of goblins. And you can take sides, ignore them or kill both of them!

("); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">Map done with Ultima Underworld Viewer)

A very particular thing about UU’s levels is that they are basically 3D playgrounds. Levels are very open and non-linear, so you can just do what you need and leave for the next level, or you can go out exploring to find entirely optional challenges and areas. What’s interesting is that due to the game’s open maps, heavy use of physical interactions and platforming, these feel much more similar to Super Mario 64 or Banjo-Kazooie’s optional objetives, instead of traditional RPG side-quests.

There’s even a certain metroidvânia aspect, as you can learn spells like water-walk, levitate and fly, then return to previous areas to explore further. Again, all this in 1992, before even Doom existed!

Kaguragawa District (Generation Xth: Code Hazard)

This is an obscure personal favorite. While dungeons aren’t as important in western RPGs anymore, in Japan there’s an entire sub-genre called “DRPG” which is based on the extremely old-school design of 1980’s Wizardry.

In these games, towns are the only safe place, the only area where you can rest, buy equipment and even level up. You set your party, go as deep into the dungeon as you can, then desperately crawl back to town to rest, always trying to push a bit further while still keeping enough resources to return.

As such, the dungeon and its encounters are designed for attrition, depleting your resources (HP, spells/mana, and healing items), until you die or are forced to return to town. It’s a game centered on resource management and repeated expeditions (Darkest Dungeon also employs this kind of logic).

Generation Xth (and its remake Operation Abyss) expands this by offering a massive dungeon with 4 different entry points — north, south, east and west — so that what you do on one part will allow you to progress further on another part, eventually reaching the center.

It’s another example of how dungeon design rules aren’t universal in CRPGs. "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">This excellent article by The Alexandrian talks about “jaquay dungeon design”, which is using the best practices of famous designer Jennell Jaquays. One of those practices is having multiple entries to the same dungeon, so that different parties can have different experiences, and that a group can flee the dungeon and try again from a different rout.

Usually this is not compatible with CRPG logic, as video game players expect to fully explore everything inside a dungeon in a single go — just imagine having to repeatedly enter and exit a dungeon in Dragon Age to progress. But it works in a DRPG, since that’s already part of the core gameplay loop.

Cosmic Cube (Wizardy IV: The Return of Werdna)

Wizardry IV is one of the hardest games ever made, but it should also be hailed as an amazingly innovative game. Here you play as Werdna, the final boss of Wizardry I. You start trapped at the bottom of the dungeon and must summon monsters as party members to fight your way out of the dungeon, killing adventurers and heroes along the way.

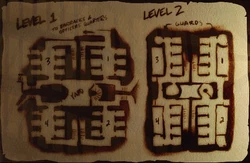

Back in the 80s, dungeon levels were restricted to something between 20x20 and 32x32 square grids. As the name suggest, the Cosmic Cube expands upon that by being a set of three interconnected dungeon floors, which must be explored as if they were a single level, with the player constantly going up and down via teleports and traps — often unintentionally!

This is here not just because of its historical value and influence, but also because it’s arguably the hardest & most iconic part of the hardest dungeon ever made. And if the map above already looks daunting, remember that the game has no auto-map. You are expected to map this by yourself, with paper and a pencil. And it was released in 1987, so there was no online maps either.

The Glow (Fallout 1)

Fallout 1 is a revolutionary RPG for several reasons, and The Glow is one of them — a radical departure from every CRPG dungeon before it.

You are sent to The Glow by the Brotherhood of Steel, who don’t expect you to survive the trip. Southeast you go, for miles and miles, far away from any other area of the game, until your surroundings becomes a hellish landscape and the radiation alone can kill you. Once you arrive, you see the crater that a nuclear warhead made. And into that crater you must go.

The Glow works best when you go in blind, without knowing what awaits you. In the first level you find only dead bodies, including a Brotherhood soldier in Power Armor, with a Holodisk talking about the horrors he faced down bellow. As you climb down, radiation keeps pilling up, more dead bodies appear, and "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">Mark Morgan’s eerie soundtrack keeps you in permanent tension.

At the bottom there’s a computer and a broken generator. If you fix the generator, you can access the computer and learn many secrets about the world of Fallout and the origin of Super Mutants. But that also enables the security robots, one of Fallout 1’s deadliest enemies, which will make your climb back up a nightmare. Unless you use your science skill to turn the security system off — this is Fallout, after all.

Ocean House Hotel (Vampire: The Masquerade — Bloodlines)

You start Bloodlines by being turned into a vampire, your first quest to deal with some punks, enjoying the full extent of your new dark powers. Your second quest does the opposite, sending you to retrieve a pendant from a haunted hotel and making you feel helpless and powerless.

The hotel acts as literal haunted house ride, building a tense atmosphere, slowly unveiling a murder story and throwing all sorts of scares at the player, from ghostly visages to blood messages on the wall. All this is combined with that sweet immersive sim-like exploration of crawling in air ducts, climbing elevator shafts, collecting keys and slowly discovering the path forward.

Bethesda tried a similar “haunted house” design several times in Fallout 3 & 4 with The Dunwich Building, Dunwich Borers and the Museum of Witchcraft. The massive quality gap between them highlights how masterfully crafted the Ocean House Hotel is, and how Bethesda’s over-reliance on combat severely cripples the range of experiences they can offer.

Vault 11 (Fallout: New Vegas)

Vault 11 could be an Arthur C. Clarke short story, but it’s a video game level. One of the best examples of environmental storytelling in a video game, it tells an elaborate, tragic and ironic tale that the player must piece together by examining the vault and a few notes lying around?

("); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">map by Eurogamer)

Its even more impressive when you remember that this unique dungeon uses the same tools and assets as the other generic vaults you’ll find in the modern Fallout games. It’s the AAA equivalent of making To The Moon in RPG Maker.

BONUS RANT: At first sight the last 3 dungeons might look the same — walk around mostly empty areas and get creeped out. However, their design principles and tools are entirely different:

- The Glow contrasts the constant pressure of radiation poisoning and the fear of the unknown with sheer curiosity. You can actually leave as soon as you get the tape on level 1, but you’ll probably want to go down all the way and uncover its secrets, even at the risk of dying.

- The Hotel is a haunted house ride in a theme park, guiding the player and actively keeping it entertained/tense as fuck as he progresses. Reading the diaries & newspapers will help understand what’s going on, but it’s a fun ride even if you ignore them.

- Vault 11 is all about the story told via notes and environmental storytelling. If you ignore them, it’s just 3 floors of empty corridors with boring trash mobs.

One could argue that The Glow is the superior one, as it’s the only where your character skills, equipment & choices actually play a role, but I think that’s beyond the point, as each offers a very unique experience.

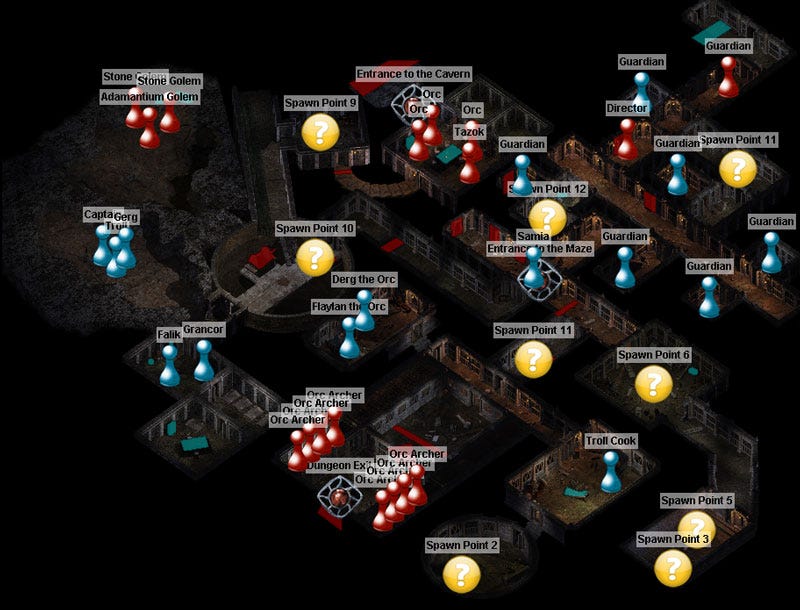

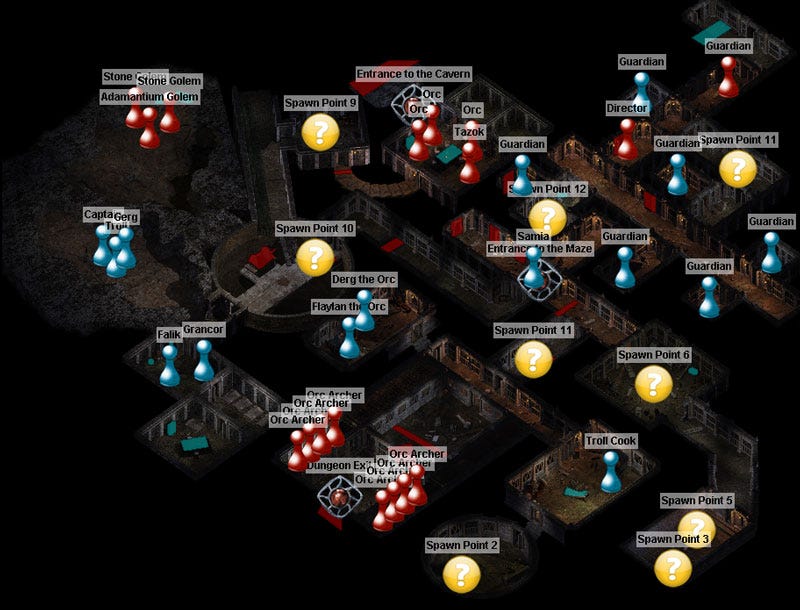

Firkraag’s Maze (Baldur’s Gate II)

Baldur’s Gate II is often considered the RPG with the best encounter design ever, and this dungeon showcases that in a very condensed combat gauntlet.

As you enter, you are ambushed by orc archers, and the only way to reach them is by finding two hidden doors and unlocking them while the orcs shoot you. After that the fun continues with a troll, werewolves, a beholder, djinns, vampires, golems, an ogre, the always-fun rival party of adventurers and, finally, a Dragon. A very big one, with layers upon layers of magical defenses.

Is not just a bunch of cool battles — almost all of them require special tactics. Trolls require fire or acid to stop regenerating, beholders require protection against magic, golems are extremely resistant to spells and weapons bellow +3, and so on. These force players to use their full arsenal of spells, items and equipment, which helps avoid the trap of “one tactic fits all” that many RPGs suffer from.

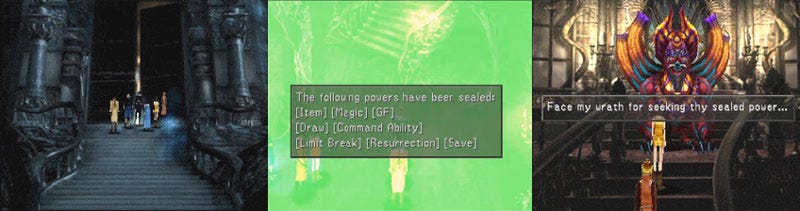

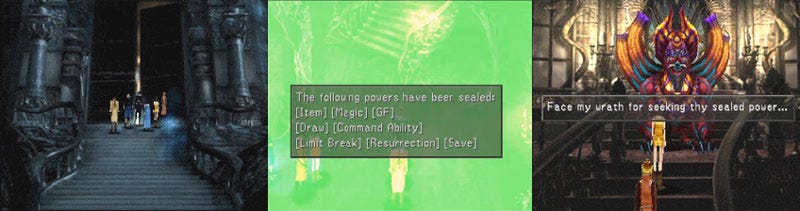

Ultimecia’s Castle (Final Fantasy VIII)

A truly bizarre end-game dungeon. As soon as you enter, you’ll lose all your party’s abilities — you won’t be able to cast spells, use items, summon, limit break, resurrect alies or even save the game! All you can do is attack.

To reclaim your abilities, you must explore the castle and defeat the eight boss encounters, each unlocking an ability. The castle looks like something out of a survival horror game, and some bosses are hidden behind puzzles that require you to split your party in two in order to solve.

By this point in the game Ultimecia is executing her evil plan of compressing time (lolwut), and to reflect that the random encounters here include over 50 different monsters from all previous areas of the game, and their level is random — including the bosses! You might face a Lv 1 Tiamat as boss, then a Lv 100 Tonberry as random encounter.

Is it balanced? Definitely not. Is it a unique and memorable way to challenge an end-game party? Definitely yes.

Durlag’s Tower (Baldur’s Gate: Tales of the Sword Coast)

Durlag was a rich and powerful dwarven hero that built an impenetrable tower to keep his family and treasures safe, then went mad. His massive tower is split into two main parts: the tower itself, composed of 4 levels, sets the stage and serves as an introduction, while the 5 underground levels show you what really happened and contain the meat of the adventure.

The story behind the tower is interesting, as are the puzzles and NPCs contained inside. The rooms are all very diverse and creative, including encounters like archers in suspended platforms full of traps, an endlessly multiplying slime or a battle on a chess board where enemies transform if they cross the board.

This is a dungeon meant for an end-game party (and an experienced player), and it demands respect. There are traps every step, combat encounters are brutal if you don’t approach them carefully and the puzzles require that you pay attention to the dungeon’s lore and its inhabitants. It can be frustrating, but also full of very satisfying “ah-ha” moments.

The infinity engine games, especially Icewind Dale I & II, have great dungeons. But Durlag’s Tower stands out among them and is arguably the best “traditional” RPG dungeon in a video game because its content is not only great, but it’s elevated by how Durlag’s Tower forces you to imerse yourself in it and fully enjoy it.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Hope this was a fun & interesting read, and if you have any suggestions of great dungeons, please leave a comment bellow on why you think they work so well. Cheers!

I don’t want to dwell much on this, so I’ll just use D&D’s definition from the 3rd Edition Dungeon Master Guide:

I like that, and it works well for both tabletop RPGs and computer & console RPGs (which I’ll hereby just call “CRPGs”). But what’s a good dungeon?

It may sound obvious, but a good dungeon in a CRPG must fit its game. For example, I enjoy the massive spaghetti-from-hell dungeons of Daggerfall:

(image captured via "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">Daggerfall Modelling)

They work because in Daggerfall you move fast, there are movement skills like flying, climbing, swimming and teleporting (thank god for teleport), combat encounters are rare & solved quickly and the first-person camera makes crossing the maze feel very satisfying, in a classic Doom kind of way.

If you used this design on Final Fantasy IX, with its slow movement, slow turn-based combat, constant random encounters and fixed camera, it would be unbearable. The same applies if you had to explore it stuck to a grid, as in Legend of Grimrock, or dragging a large party around, as in Baldur’s Gate.

Similarly, Demon’s Souls Tower of Latria is an amazing dungeon but it would probably suck in tabletop or even in an isometric CRPG, as so much of what makes it so great is tied to directly maneuvering your hero across 3D space.

Again, it sounds obvious, but think how different from tabletop RPGs that is.

There’s an entire industry of indie publishing houses making award-winning “system-agnostic” dungeons and campaigns that you can play using almost any RPG ruleset, from D&D to GURPS, Warhammer, Call of Cthulhu, Shadowrun or even Toon.

Meanwhile, just imagine playing a dungeon from AssAssCreed: Odyssey as Mass Effect’s Shepard, who can’t even jump. Mass Effect simply doesn’t offer the tools to explore Odyssey’s world. And there’s no DM to go “uh… just roll a d20 and try to get 14 or more”, all that the Mass Effect toolbox would allow is for you to press A and see a cutscene of Shepard climbing. How dull.

So CRPG dungeon design is intrinsically tied to the “verbs” that are available to the player — if can he jump, climb, sneak, fly, teleport, swim, fight ranged enemies, lockpick, break objects, directly maneuver with objects, talk to NPCs, push objects, etc.

Obviously the perspective, combat style, party size and skills also affect the dungeon design, but even things like the UI can radically alter how a dungeon is designed. For example, back in the 80s CRPGs didn’t have in-game maps, so you were expected to draw your own maps on paper — some CRPGs even included graph paper inside the game box.

Since the designers knew players were mapping every step, it was common to have traps that would spin or teleport the player away — without any warning! By the time you figured it out you weren’t where you expected to be, you had to erase half of your map and try to find where it went wrong.

This was a traditional challenge in most 80s CRPGs, like Wizardry, Might & Magic, Dungeon Master, Bard’s Tale and the Gold Box series, all of which were first-person RPGs. But this sort of challenge doesn’t work in isometric or third-person RPGs, and it vanished once in-game maps became a thing.

Think about that: a change in UI drastically changed how dungeons were designed and played in CRPGs!

So, while there are many resources on dungeon design for tabletop RPGs, such as "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">JohnnFour’s 5 Room Dungeon, "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">Kent David Kelly’s trilogy of books or "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">this cool article on dungeon maps, it’s much harder to do something like that for CRPGs. If you are making a first-person RPG, then "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">Luke McMillan’s article on FPS line of sight can be as useful than any tabletop reference, but the same article would be almost useless when designing an isometric RPG.

Therefore, what we’ll do for the remaining of this article is take a look at some really great dungeons and try to see what makes them so great, hopefully learning something in the progress.

So here’s my personal selection of some amazing dungeons:

Shurugeon Castle (Wizards & Warriors)

As you enter this haunted castle, the ghost of knight D’Soto appears and tells you a demon took over the castle. The demon is in the throne room, which you can easily reach, but he’s immortal, immune to your attacks.

As you explore the castle for clues, a narrator describes the most important areas and set pieces, while the demon constantly taunts you and sends his minions to ambush you. Soon you find D’Soto’s squire, who fights alongside you and tells that he found a way to kill the demon by collecting 5 items and performing a ritual. He gives you one of the items, the other 4 must be found by fighting an undead guard, solving a puzzle, uncovering a hidden path and bartering/stealing/killing a vampire — all the game’s main interaction “verbs”.

It’s a classic and “gamey” dungeon design, but it’s extremely well-executed and also makes full use of the “video gamey” part — the dungeon is interconnected and feels like a real place, while also being very “tactile”, requiring you to swim across the moat, lower the draw-bridge, flip switches, ride elevators, jump down from the roof, use items to open secret doors and other interactions that feel great with the game’s FPS-like view and controls.

Of all the dungeons in this list, Shurugeon Castle is the most “generic”. I placed it first because I think that makes it an excellent showcase of great dungeon design without relying on excellent writers, creative concepts or very particular game mechanics.

Sen’s Fortress (Dark Souls)

Dark Souls’ level design is legendary, and Sen’s Fortress is its most iconic dungeon. A lot was written about it already, I just want to add one thing: I think it’s the best use of 3D movement in any RPG ever.

Sure, the layout, the enemies and the secrets are all cool, but the core of the dungeon is fighting and maneuvering your character while avoiding traps, falls and attacks that might push you over.

Clever use of 3D movement is something criminally underused in RPGs, despite the shift towards third-person cameras and heavy action focus, as their controls are usually very floaty and falling to your death is frustrating. Remember how Mass Effect: Andromeda gave you a jetpack, but only offered simple platforming sections that instantly rescued you if you fell down.

Sen’s Fortress demands carefully positioning & maneuvering, and not only for exploration, but as vital part of the dungeon’s combat.

Level 1 (Ultima Underworld)

It’s honestly mind-blowing how UU not only invented 3D RPGs and immersive sims back in 1992, but also did it so goddamn well. It’s very first level has diverse combat encounters, platforming, logic puzzles, keys to be found, levers to be pulled, a river with strong current to swim across, secret areas, lore bits and hints about future challenges, two different paths to the next level and also several inhabitants you can talk to — including two warring factions of goblins. And you can take sides, ignore them or kill both of them!

("); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">Map done with Ultima Underworld Viewer)

A very particular thing about UU’s levels is that they are basically 3D playgrounds. Levels are very open and non-linear, so you can just do what you need and leave for the next level, or you can go out exploring to find entirely optional challenges and areas. What’s interesting is that due to the game’s open maps, heavy use of physical interactions and platforming, these feel much more similar to Super Mario 64 or Banjo-Kazooie’s optional objetives, instead of traditional RPG side-quests.

There’s even a certain metroidvânia aspect, as you can learn spells like water-walk, levitate and fly, then return to previous areas to explore further. Again, all this in 1992, before even Doom existed!

Kaguragawa District (Generation Xth: Code Hazard)

This is an obscure personal favorite. While dungeons aren’t as important in western RPGs anymore, in Japan there’s an entire sub-genre called “DRPG” which is based on the extremely old-school design of 1980’s Wizardry.

In these games, towns are the only safe place, the only area where you can rest, buy equipment and even level up. You set your party, go as deep into the dungeon as you can, then desperately crawl back to town to rest, always trying to push a bit further while still keeping enough resources to return.

As such, the dungeon and its encounters are designed for attrition, depleting your resources (HP, spells/mana, and healing items), until you die or are forced to return to town. It’s a game centered on resource management and repeated expeditions (Darkest Dungeon also employs this kind of logic).

Generation Xth (and its remake Operation Abyss) expands this by offering a massive dungeon with 4 different entry points — north, south, east and west — so that what you do on one part will allow you to progress further on another part, eventually reaching the center.

It’s another example of how dungeon design rules aren’t universal in CRPGs. "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">This excellent article by The Alexandrian talks about “jaquay dungeon design”, which is using the best practices of famous designer Jennell Jaquays. One of those practices is having multiple entries to the same dungeon, so that different parties can have different experiences, and that a group can flee the dungeon and try again from a different rout.

Usually this is not compatible with CRPG logic, as video game players expect to fully explore everything inside a dungeon in a single go — just imagine having to repeatedly enter and exit a dungeon in Dragon Age to progress. But it works in a DRPG, since that’s already part of the core gameplay loop.

Cosmic Cube (Wizardy IV: The Return of Werdna)

Wizardry IV is one of the hardest games ever made, but it should also be hailed as an amazingly innovative game. Here you play as Werdna, the final boss of Wizardry I. You start trapped at the bottom of the dungeon and must summon monsters as party members to fight your way out of the dungeon, killing adventurers and heroes along the way.

Back in the 80s, dungeon levels were restricted to something between 20x20 and 32x32 square grids. As the name suggest, the Cosmic Cube expands upon that by being a set of three interconnected dungeon floors, which must be explored as if they were a single level, with the player constantly going up and down via teleports and traps — often unintentionally!

This is here not just because of its historical value and influence, but also because it’s arguably the hardest & most iconic part of the hardest dungeon ever made. And if the map above already looks daunting, remember that the game has no auto-map. You are expected to map this by yourself, with paper and a pencil. And it was released in 1987, so there was no online maps either.

The Glow (Fallout 1)

Fallout 1 is a revolutionary RPG for several reasons, and The Glow is one of them — a radical departure from every CRPG dungeon before it.

You are sent to The Glow by the Brotherhood of Steel, who don’t expect you to survive the trip. Southeast you go, for miles and miles, far away from any other area of the game, until your surroundings becomes a hellish landscape and the radiation alone can kill you. Once you arrive, you see the crater that a nuclear warhead made. And into that crater you must go.

The Glow works best when you go in blind, without knowing what awaits you. In the first level you find only dead bodies, including a Brotherhood soldier in Power Armor, with a Holodisk talking about the horrors he faced down bellow. As you climb down, radiation keeps pilling up, more dead bodies appear, and "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">Mark Morgan’s eerie soundtrack keeps you in permanent tension.

At the bottom there’s a computer and a broken generator. If you fix the generator, you can access the computer and learn many secrets about the world of Fallout and the origin of Super Mutants. But that also enables the security robots, one of Fallout 1’s deadliest enemies, which will make your climb back up a nightmare. Unless you use your science skill to turn the security system off — this is Fallout, after all.

Ocean House Hotel (Vampire: The Masquerade — Bloodlines)

You start Bloodlines by being turned into a vampire, your first quest to deal with some punks, enjoying the full extent of your new dark powers. Your second quest does the opposite, sending you to retrieve a pendant from a haunted hotel and making you feel helpless and powerless.

The hotel acts as literal haunted house ride, building a tense atmosphere, slowly unveiling a murder story and throwing all sorts of scares at the player, from ghostly visages to blood messages on the wall. All this is combined with that sweet immersive sim-like exploration of crawling in air ducts, climbing elevator shafts, collecting keys and slowly discovering the path forward.

Bethesda tried a similar “haunted house” design several times in Fallout 3 & 4 with The Dunwich Building, Dunwich Borers and the Museum of Witchcraft. The massive quality gap between them highlights how masterfully crafted the Ocean House Hotel is, and how Bethesda’s over-reliance on combat severely cripples the range of experiences they can offer.

Vault 11 (Fallout: New Vegas)

Vault 11 could be an Arthur C. Clarke short story, but it’s a video game level. One of the best examples of environmental storytelling in a video game, it tells an elaborate, tragic and ironic tale that the player must piece together by examining the vault and a few notes lying around?

("); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);">map by Eurogamer)

Its even more impressive when you remember that this unique dungeon uses the same tools and assets as the other generic vaults you’ll find in the modern Fallout games. It’s the AAA equivalent of making To The Moon in RPG Maker.

BONUS RANT: At first sight the last 3 dungeons might look the same — walk around mostly empty areas and get creeped out. However, their design principles and tools are entirely different:

- The Glow contrasts the constant pressure of radiation poisoning and the fear of the unknown with sheer curiosity. You can actually leave as soon as you get the tape on level 1, but you’ll probably want to go down all the way and uncover its secrets, even at the risk of dying.

- The Hotel is a haunted house ride in a theme park, guiding the player and actively keeping it entertained/tense as fuck as he progresses. Reading the diaries & newspapers will help understand what’s going on, but it’s a fun ride even if you ignore them.

- Vault 11 is all about the story told via notes and environmental storytelling. If you ignore them, it’s just 3 floors of empty corridors with boring trash mobs.

One could argue that The Glow is the superior one, as it’s the only where your character skills, equipment & choices actually play a role, but I think that’s beyond the point, as each offers a very unique experience.

Firkraag’s Maze (Baldur’s Gate II)

Baldur’s Gate II is often considered the RPG with the best encounter design ever, and this dungeon showcases that in a very condensed combat gauntlet.

As you enter, you are ambushed by orc archers, and the only way to reach them is by finding two hidden doors and unlocking them while the orcs shoot you. After that the fun continues with a troll, werewolves, a beholder, djinns, vampires, golems, an ogre, the always-fun rival party of adventurers and, finally, a Dragon. A very big one, with layers upon layers of magical defenses.

Is not just a bunch of cool battles — almost all of them require special tactics. Trolls require fire or acid to stop regenerating, beholders require protection against magic, golems are extremely resistant to spells and weapons bellow +3, and so on. These force players to use their full arsenal of spells, items and equipment, which helps avoid the trap of “one tactic fits all” that many RPGs suffer from.

Ultimecia’s Castle (Final Fantasy VIII)

A truly bizarre end-game dungeon. As soon as you enter, you’ll lose all your party’s abilities — you won’t be able to cast spells, use items, summon, limit break, resurrect alies or even save the game! All you can do is attack.

To reclaim your abilities, you must explore the castle and defeat the eight boss encounters, each unlocking an ability. The castle looks like something out of a survival horror game, and some bosses are hidden behind puzzles that require you to split your party in two in order to solve.

By this point in the game Ultimecia is executing her evil plan of compressing time (lolwut), and to reflect that the random encounters here include over 50 different monsters from all previous areas of the game, and their level is random — including the bosses! You might face a Lv 1 Tiamat as boss, then a Lv 100 Tonberry as random encounter.

Is it balanced? Definitely not. Is it a unique and memorable way to challenge an end-game party? Definitely yes.

Durlag’s Tower (Baldur’s Gate: Tales of the Sword Coast)

Durlag was a rich and powerful dwarven hero that built an impenetrable tower to keep his family and treasures safe, then went mad. His massive tower is split into two main parts: the tower itself, composed of 4 levels, sets the stage and serves as an introduction, while the 5 underground levels show you what really happened and contain the meat of the adventure.

The story behind the tower is interesting, as are the puzzles and NPCs contained inside. The rooms are all very diverse and creative, including encounters like archers in suspended platforms full of traps, an endlessly multiplying slime or a battle on a chess board where enemies transform if they cross the board.

This is a dungeon meant for an end-game party (and an experienced player), and it demands respect. There are traps every step, combat encounters are brutal if you don’t approach them carefully and the puzzles require that you pay attention to the dungeon’s lore and its inhabitants. It can be frustrating, but also full of very satisfying “ah-ha” moments.

The infinity engine games, especially Icewind Dale I & II, have great dungeons. But Durlag’s Tower stands out among them and is arguably the best “traditional” RPG dungeon in a video game because its content is not only great, but it’s elevated by how Durlag’s Tower forces you to imerse yourself in it and fully enjoy it.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Hope this was a fun & interesting read, and if you have any suggestions of great dungeons, please leave a comment bellow on why you think they work so well. Cheers!

Would be curious in hearing the Codex's thoughts, especially of Melan , which I cited

Last edited by a moderator: