Boleskine

Arcane

- Joined

- Sep 12, 2013

- Messages

- 4,045

So far there's one article from a couple weeks ago, but more will be coming.

https://adventuregamers.com/articles/view/32711

https://adventuregamers.com/articles/view/32711

A Sierra Retrospective: Part 1 - The Pioneers of Adventure

Written by Shawn Mills — May 5, 2017

King’s Quest. Space Quest. Leisure Suit Larry. All seminal games in adventure game history. All created by the same company.

Dig deeper into the catalog and there are dozens more equally memorable titles. Quest for Glory. Police Quest. Gabriel Knight.

Delve further still and there are more hidden gems. Manhunter. Eco Quest. Laura Bow.

These games, and many more, were created out of the Oakhurst California studios of Sierra On-Line, in a hectic period between the release of King’s Quest in 1983 and the early ‘90s when the effects of the public float began to be felt.

It was a golden age for Sierra and adventure games.

The story of Sierra is unique to its era. The Apple II was released in 1977 and brought personal computing to the family home. With that, a new industry was born. Computer games.

At the forefront of these games was the adventure.

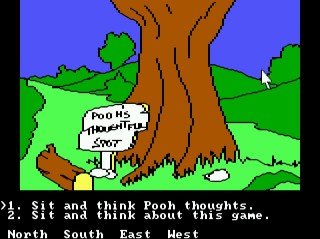

Mystery House, the first graphic adventure

Roberta Williams had been playing text adventures on her Apple II, but she felt something was missing. What the games needed were pictures. She convinced her husband Ken to help and between them they created Mystery House, the first graphic adventure game. It was a massive success and led to the founding of Sierra On-Line and a catalog of dozens of adventure games.

Along with Williams herself, who went on to create King’s Quest, Sierra also developed an enviable stable of talented designers, people such as Jane Jensen (Gabriel Knight), Al Lowe (Leisure Suit Larry) and Lori and Corey Cole (Quest for Glory). They employed the best musicians, writers and artists available to create their games. And they also worked with some of entertainment’s biggest names, like Disney and Jim Henson.

At a time when there weren’t established rules for how to make games, development was pioneered by Sierra and its contemporaries. Each new advance in technology pushed production in new directions and allowed for more expansive storytelling.

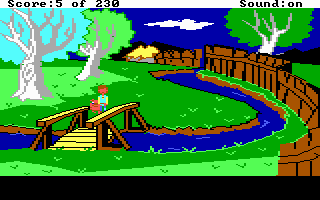

Ken and Roberta Williams

In 2014, Ken and Roberta were honored with the Gaming Industry Award: “With multiple highly successful franchises, Sierra was renowned for pushing the boundaries of writing, game design, animation, sound, music, and with the advent of CD-ROM, even acting. Today’s gaming storytellers stand on Sierra’s shoulders.”

Over the course of this ongoing retrospective article series, I’ll delve into a few specific areas of Sierra’s history. My hope is to shine light on some of the unique aspects of this company and share some stories about those times from the people who lived them.

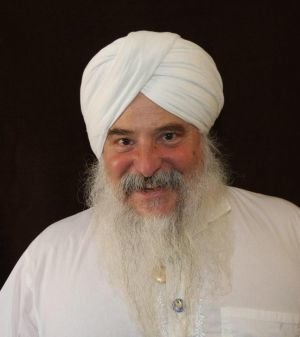

One such person, although a lesser-known name among Sierra luminaries, is Guruka Singh Khalsa. Guruka was Sierra’s first producer, a creative and administrative role which also gave him broad oversight of the production for all the company’s games.

“There was this peak where the creative juices drove Sierra. It was very much about the soul of the game. A game that can touch you deeply and make you go wow,” Guruka claims.

Christy Marx, an accomplished author and TV writer, wrote and designed two adventure games for Sierra, Conquests of Camelot and Conquests of the Longbow. She agrees about the creativity of Sierra at the time.

“When I first got there, everything was open and free and the creativity flowed. We had a good time making games. We had fun. Nobody knew entirely what they were doing because games were so new, so we got to experiment.”

Christy Marx graces the cover of Sierra Magazine

Adventure games start with an idea. Sometimes that idea came from the designer, sometimes it came from elsewhere. For Christy, the idea for both her games came from the person who practically invented the graphic adventure genre, Roberta Williams.

“I believe it was Roberta who said they'd been thinking about a King Arthur game. I quickly said that we'd be happy to do that type of game, and we agreed upon that,” Christy says.

For Conquests of the Longbow, the process was more amusing. “I was in the earliest stages of thinking about a game based on Greek mythology using goddesses. I was aware that a number of Robin Hood movie projects had been announced, but when Roberta mentioned them to me I didn't pay attention. It didn't relate to what I was thinking about.”

“A day or so later after the first mention, Roberta said to me, ‘I had this dream last night that you were doing a Robin Hood game.’ I suddenly realized that what she was really doing was dropping hints that they wanted me to do a Robin Hood game.”

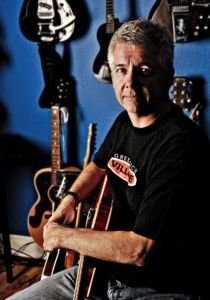

Josh Mandel had a different experience. As Director of Product Design, he and the other designers would meet with company owner Ken Williams and Creative Director Bill Davis weekly to discuss game proposals.

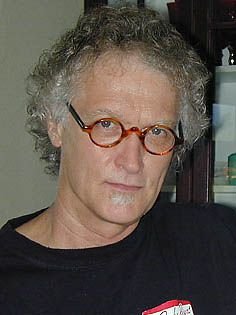

An imposing Josh Mandel

“Every week we would submit two game proposals. We learned to make these proposals very short because Ken didn’t have the patience. He would read a couple of paragraphs and if you hadn’t grabbed his interest by then you probably weren’t going to. Bill Davis wasn’t this way; he was thoughtful and would read through the proposals and work to understand them.”

It was out of one of these meetings that Josh developed the initial idea for Laura Bow 2: The Dagger of Amon Ra, a game which Bruce Balfour would go on to design and develop.

“My proposal was about a museum. I didn’t have a name for it but it was a museum with a display of a ceremonial Egyptian dagger that gets lost. Basically, the game, but summed up in a couple of paragraphs,” Josh explains.

Once an initial concept was approved and a designer assigned to develop it, a producer would be added to the mix. While the designer concentrated on the game design process, the producer’s job was to handle the production side of the equation, along with providing an oversight role for the creative side.

The producer and designer worked together in an almost symbiotic way. When the producer was assigned a rough budget by management, they would be required to break it down into the individual parts necessary to create the game. How many artists should be involved? How many programmers? What musicians would be needed?

But these positions couldn’t be defined until the designer had started to form their ideas together into a coherent design.

Producers like Guruka Singh Khalsa were deeply involved in the early stages of design. He has vivid memories of working with designer Christy Marx on Conquests of Camelot.

Senior Producer Guruka Singh Khalsa (post-Sierra)

“Sitting on the grass. Outside. Under a tree. Christy and I with a legal pad and pen. Sketching stuff out. Talking about puzzle logic and getting really excited about twists we could make in the puzzles. Mapping out the sequence of the character arc in the game and sparking each other creatively. It was very informal,” he says. “That was before we did formal storyboards up on the wall. It was the creative game ideas in the early stages where we would answer questions like ‘How can we make this game more fun?’ ‘How can we make the puzzles more fun?’”

Mandel’s first role at Sierra was a Junior Producer, so he has unique knowledge of both sides of the process. He says the two most important roles would be filled first: the art designer or lead artist, and the lead programmer.

“Once the designer had some definite ideas about what the game was going to entail they would meet with the lead artist and discuss the style of the game. They might also meet with the lead programmer and talk about the larger issues of the game. Was it going to need any special programming sequences? Would it use the in-house (SCI) engine?”

As the designer progressed further, the producer would work with them to refine the number of staff required to create the game.

Josh goes on to say, “You’d have a record of all the programmers and a guide to when each one was expected to come off of whatever project they were currently on. You looked to see who was going to be available around the time you were going to need them. They might not be available when the team was being formed but they might come on later. The same thing for the artists and the musicians.”

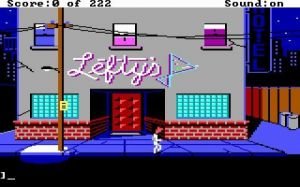

Codename: ICEMAN was not one of Sierra's finer achievements

This casual design relationship between designer and producer contributed to some big hits for Sierra, but it also caused some problems, as Guruka says happened with Codename: ICEMAN.

“Iceman was the worst designed game ever. In fact, the rooms didn’t make any sense. If you actually mapped out the rooms there was no way to get from one to another. And it had all kinds of graphical bugs and logic bugs in it.”

“Around that point, we said everything has to be storyboarded out, every game has to be mapped out. We actually completely changed our production methods. A lot of this was because it was early days. It was learn by making mistakes,” Guruka says.

This was a symptom of the company’s design philosophy at the time, Mandel explains. “A designer would get a game and then they would go off and do their own thing,” he claims. “Nobody really checked it over. Nobody said, here’s the flaws in your design, here are your dead ends and so on.”

With all the pieces in place, production of a game followed a standard process. The designer would develop a section of the game and the artists would create the background and animation artwork to go along with that design. These assets would be delivered to the programmers who would implement them into the game, again using the design document as a guide. This same process would be repeated for the musicians and the writers.

With so many moving parts, everything didn’t always go to plan. There was a constant pressure for producers and designers to deliver their game on schedule and on budget.

Teams were always under the gun, including the staff on Freddy Pharkas: Frontier Pharmacist

The possibility of people having to be laid off was a constant. According to Mandel, “it was normal for every team to be told that if we don’t pull this in on schedule and on budget we’re going to have to lay people off,” he says. “That was always the threat that was hung over us to keep things on track.”

Things were just about never on track.

“There was constant juggling of personnel. If things had gone too far off schedule then the programmer I had working on the game… they might pull him off and say, nope, you gotta work on the next game now. That would just increase the delay of my game,” says Josh.

By the end, though, a game would be created.

Mandel describes his best memory from his time at Sierra. It was at the end of production on Freddy Pharkas: Frontier Pharmacist, his first design credit, and he vividly recalls watching the boxes come off the production line.

“Watching the boxes of Freddy Pharkas coming off the assembly line, filled and shrinkwrapped and put in cases to be sent out. Maybe that memory is the one that comes to mind above almost everything else because I wasn’t getting enough sleep for the duration of the project or at least the crunch time. I have never felt such a strange and powerful mix of emotions. Most of those emotions were positive, seeing the game in physical form for the first time. What a sense of accomplishment and dread that now it was out of our hands; they were going to go out and the first person who bought it was going to get a crash bug that everyone else was going to get. So there was abject horror, there was pride, and sleepiness and confusion. I really cherish the vibrancy of that memory.”

The philosopher Plato once said about music that “It gives soul to the universe, wings to the mind, and flight to the imagination.” Believing this same principle, music was a vital part of Sierra’s development process, even as the technology changed from PC speakers to midi and later to digital music along the way. In our next article, we’ll take a closer look at how Sierra prioritized music as an important way of bringing players into its game worlds.

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)

![Glory to Codexia! [2012] Codex 2012](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_slushfund2012.png)

![Have Many Potato [2013] Codex 2013](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_potato2013.png)