-

Welcome to rpgcodex.net, a site dedicated to discussing computer based role-playing games in a free and open fashion. We're less strict than other forums, but please refer to the rules.

"This message is awaiting moderator approval": All new users must pass through our moderation queue before they will be able to post normally. Until your account has "passed" your posts will only be visible to yourself (and moderators) until they are approved. Give us a week to get around to approving / deleting / ignoring your mundane opinion on crap before hassling us about it. Once you have passed the moderation period (think of it as a test), you will be able to post normally, just like all the other retards.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Vapourware Asylum (from creator of Scratches) - coming March 6th

- Thread starter Humanity has risen!

- Start date

Great Deceiver

Arcane

- Joined

- Aug 10, 2012

- Messages

- 5,906

The trailer's idea is pretty cool (70/80's horror flick trailer aesthetic), but they really needed to find a narrator without an accent for it to really work.

Boleskine

Arcane

- Joined

- Sep 12, 2013

- Messages

- 4,045

https://steamcommunity.com/games/asylum/announcements/detail/1776011874558802996

Why is ASYLUM taking so long?!

Feb 26 @ 4:35pm - AgustinCordes

Greetings from a dimension of ineffable cosmic hideousness! It’s about time I made this post as some of you keep asking this question, not to mention lighting torches and raising pitchforks. I’ll try to resume as best as possible our vision for ASYLUM, what we’re trying to achieve with the game, and why the darned thing is taking so long.

This is a long post, so grab a cup of coffee or beer and enjoy.

THE OBVIOUS

We’re a very small indie team —essentially three people— operating on a shoestring budget. We tried going with publishers several times but either we found they didn’t share our vision, demanded too much or gave too little. There’s definitely good people out there, but we could never find the right partner for the project.

Moreover, the conditions in Argentina, where we live, aren’t always the best. We’re fortunate to have struck a balance between our personal lives and work, but often it’s not that easy. Thanks to the generosity of Kickstarter backers, we were able to finance 50% of the project, the other half being self-funded from our own pocket. It’s very, very hard to finance a large game project, especially one as atypical as ASYLUM.

So we did what we humanly could throughout all these years, responding to industry changes and juggling with the circumstances. Of course we did mistakes, too. We truly regret the game has taken this long to develop, but one thing has never changed…

THE VISION

ASYLUM was born out of sheer love of adventure games and horror, as well as the experience with my first project Scratches. It was always meant to be a more ambitious take on the ideas introduced in that game, which miraculously took only three years to develop. ASYLUM is at its heart a classic point-and-click adventure, but feels different. Its ultimate goal is to be a modern and updated take on the traditional adventure game.

I’m even tempted to say Interactive Fiction. It recently became obvious to me how much companies like Infocom have influenced ASYLUM (and Scratches). The layout of locations and emphasis on exploration is very similar to your average Infocom game — in fact, the entirety of ASYLUM could be rewritten as an IF game and still work well.

So exploration is a key aspect we kept in mind when designing the…

LOCATION

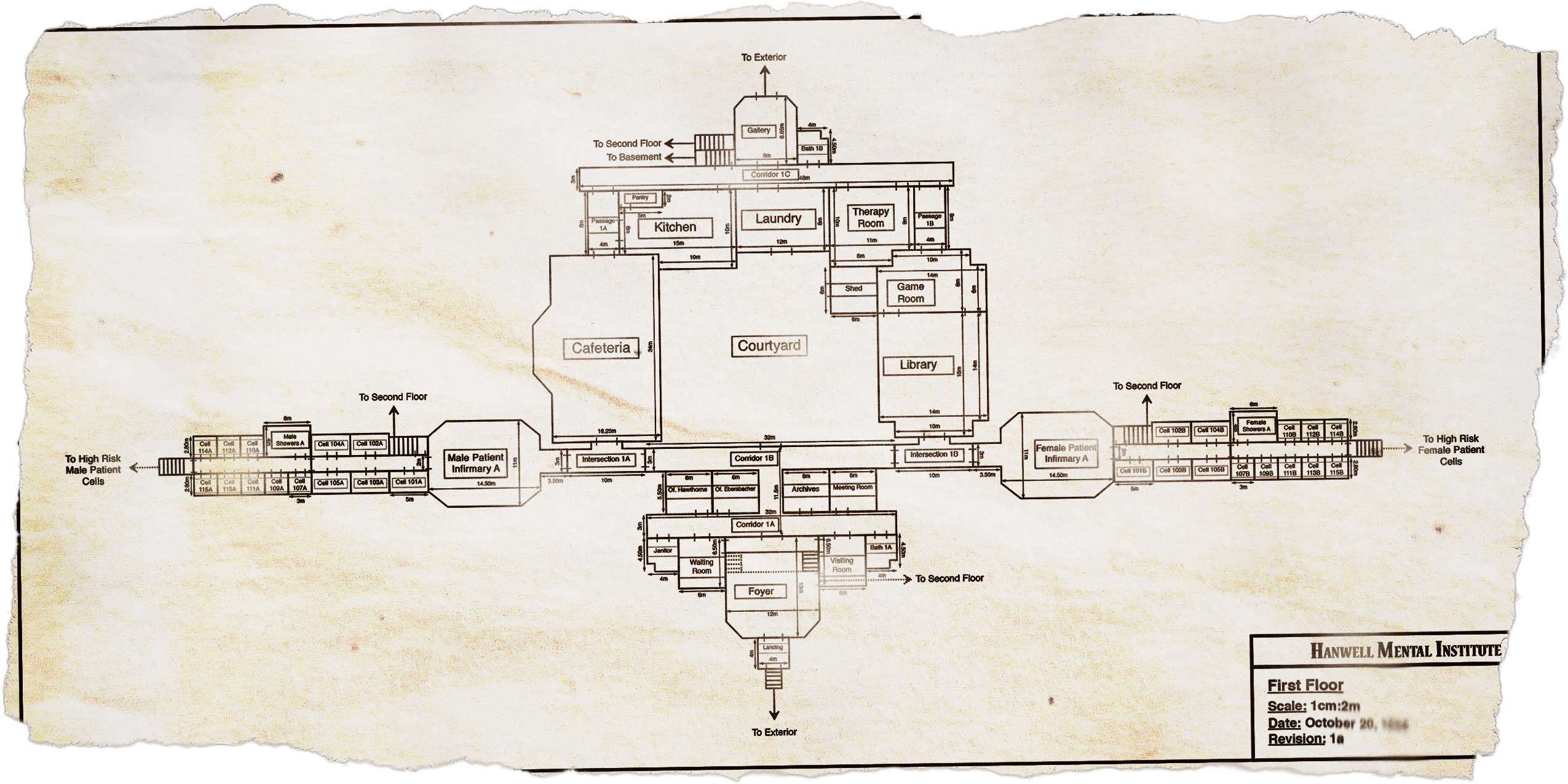

Another goal was to give players the chance to explore virtual asylum that felt like the real deal. And yes, we went overboard:

Turns out asylums are rather big places:

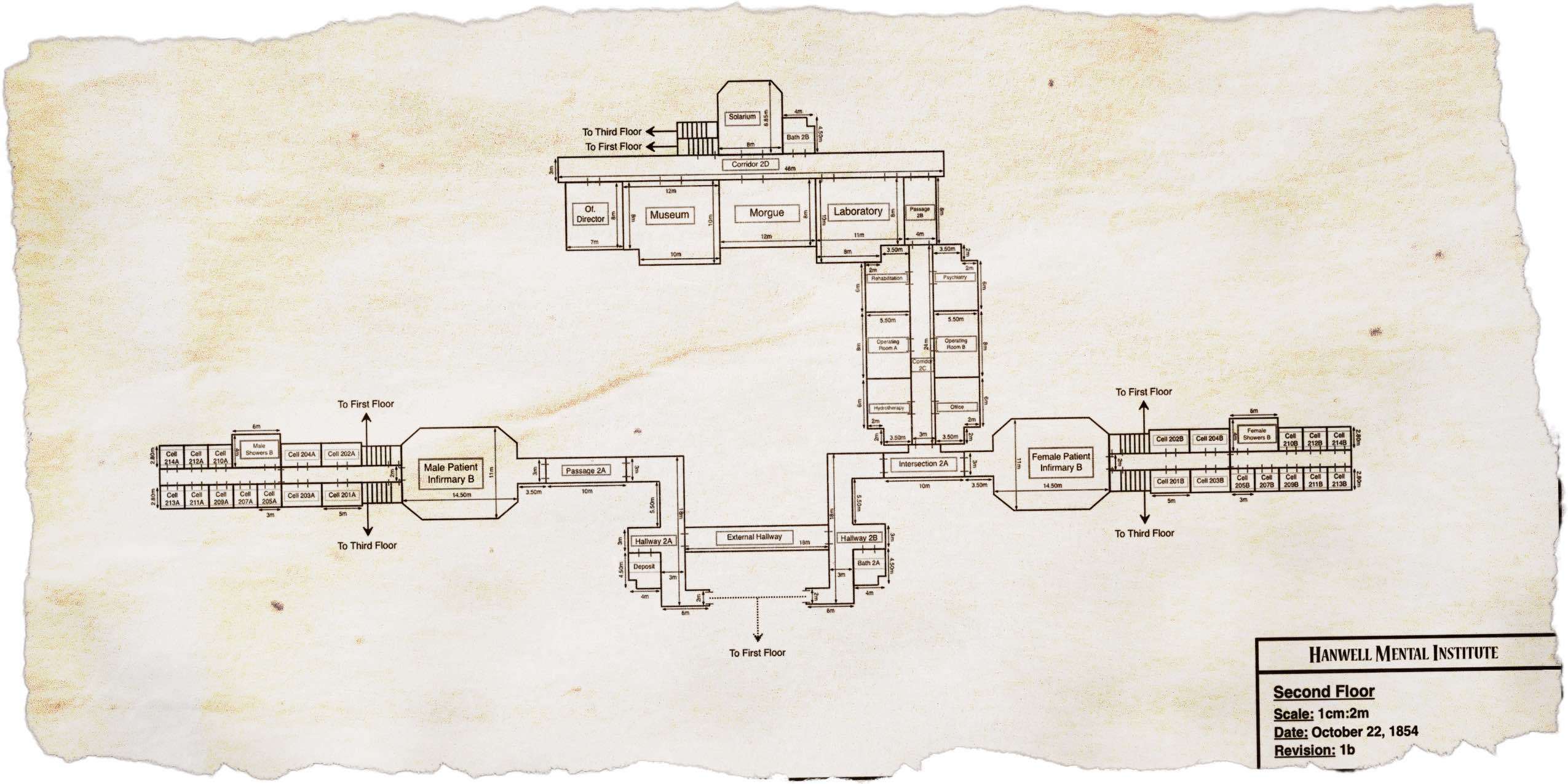

Yeah. They have many floors too:

AND basements, but enough of these blueprints. Keep in mind that each one of those rooms have a distinct look and feel, as well as tons of little details to discover and cherish, as we don’t want to bore you to death. The whole location has been painstakingly designed and eventually you’ll have full liberty to explore it as you want. It’s huge, intricate, filled with spooky secrets, and we estimate you’ll spend several hours just exploring the whole place.

GAMEPLAY

It’s no secret the game is a love letter to adventure games, with a twist. We iterated over the interface several times until we found the right approach and balance. At its core, ASYLUM works essentially like Scratches: it’s node-based with discrete movements.

This tried-and-true technique is ideal for adventure games as it allows us to create very detailed graphics for the game, as well as avoid repetition. While the presentation might be somewhat jarring for some players who aren't familiar with classic adventure games, we found that you quickly stop thinking about it after playing for a short bit. Case in point, Serena has been downloaded over 2.000.000 times with close to no friction when it comes to its presentation. Of course, fans of Scratches know the format can work very well.

But we aren’t just making a bigger and badder Scratches here — we went one step further by integrating actual 3D elements with these pre-rendered nodes, tweaking stuff as much as possible to make it seem as if you were playing a full 3D game, for instance adding breathe and walking effects.

(before you ask “why not go full 3D?”, we did consider it at some point and realized it was virtually impossible to do, not to mention that it didn’t “feel” right for the game)

So, imagine that we have these highly detailed rooms modeled with a 3D editor and each node is an actual cube. Fine, then we need to export 6 textures per node. Some rooms have up to 12 nodes. We connect the nodes together, add effects such as fog, dust, sounds… and this is just to move around the atmospheric locations. Interactions are a whole different story.

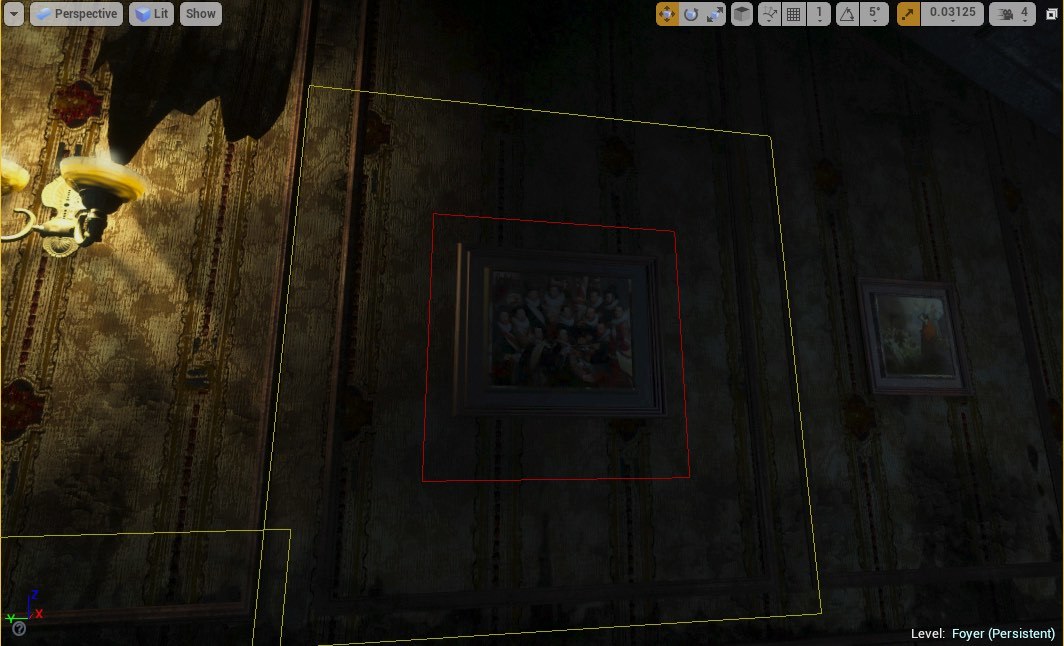

The nodes are flat textures (yes, really, people still don’t believe this), so any change in a scene has to be represented by another texture. When you pick something up, we must replace that portion of the scene with another texture patch. And of course we also need to define hotspots so that you can interact with stuff:

Every single thing you see in the game is a hotspot. Well, you don’t see the hotspot, but it’s there. It’s not like we can say “oh hey, when the player clicks on this painting…”, no, we need to manually define the interactive region. This is more straightforward in a 2D adventure game because there are proportionally much less scenes. But consider this: 80 scenes in a 2D adventure are already quite a lot — in pseudo-3D like ASYLUM with an average 4-5 nodes per room, those 80 scenes become 400. And this is in fact the amount of nodes we are estimating have been rendered for the game.

WRITING

Haha, see? See why we’re losing our minds with this project? But wait! You don’t know everything yet. Because I hate repetition in adventure games; I really dislike when you click on a hotspot and get the same canned response over and over again (i.e.: “The ocean looks serene and comforting.”). It especially feels artificial when you click a couple of times to check if the protagonist has something else to say and turns out the feedback is exactly the same.

So, we implemented a complex system to avoid that and wrote up to 12 different responses per hotspot.

Not just that, but a number of responses are tied to the mood of the protagonist (optimistic, somber, desperate), so some responses will be triggered after certain situations occur in the game. Imagine going back to a room and discovering that the protagonist has a completely different perspective on stuff. That previous line about the ocean turns into “Just as we came from them, one day we’ll all return to the eternal waters”. Cheerful.

The sheet where we are keeping all this is BONKERS:

CHARACTERS

It’s estimated that just the modeling, texturing and rigging of a character costs $8000 in the industry. That is excluding animations. We have 4 main NPCs here, and 5 minor roles. Considering the animations, the "pro" industry price for our complete cast would have been the entire budget of the game. Games. Are. Expensive.

As an indie team we have options, but still, our inability to afford such industry costs resulted in a huge deal of time and headaches creating these characters alone. They may not look AAA, but they more than get the job done and we are happy with the results.

In fact, we estimate that the Hanwell Mental Institute alone, where the game takes place, took us 3-4 years to create, and then another 2-3 years for the characters. There’s many other aspects of course, but location and characters by far took us the most time of development.

STORY

The final piece of the puzzle is the story. Writing down the script was the first task that was ever done for the game many aeons ago. It’s thorough, twisty, and full of surprises (and we somehow managed to keep it secret for 10 years!). Our undying confidence in it is the reason why we spent so much time and effort working on this project. It’s the ultimate requirement to fulfill that original vision, to ensure the game does justice to the story that was written in the first place.

It’s far more ambitious and engrossing than Scratches, which was praised for its story — case in point, Scratches was designed to make sure you never get to see any characters, with conversations always happening over the phone. However, this meant that great part of the plot always felt detached somehow, since there’s this rich array of characters you never see. The story in ASYLUM simply wouldn’t work that way. You need to see these people and even the past inmates through flashbacks. Come think of it, that’s yet another aspect that took us a great deal of time: ASYLUM has countless of cutscenes everywhere with characters and drama, many times more than Scratches… but I’ll stop here.

AND NOW... THE STATUS UPDATE

That was merely a general overview. There’s tons of angles behind the development that I’m not discussing here, but hopefully you’ll understand a bit better our position and why this is taking so long. Ultimately, we don’t want to make a passable game but one that surprises you and is never forgotten. Turns out making that sort of game today implies a vast amount of work.

But still, we keep making strides and enjoying a great momentum: as the game keeps growing in popularity (27.000 wishlists now!), we’re eyeing to have a complete playable build (beta) within 2-3 months. The vast majority of assets are ready and we're now focused on implementing puzzles and interactions.

As expected, this phase of implementing game logic is comparatively happening much faster than all the previous years of production. To put it into perspective, imagine that we spent 90% preparing stuff and 10% putting everything together. This happens often with adventure games that depend a lot on narrative content and not so much on prototyping, AI, randomly generated content, etc.

As for the big question of when it will be ready, we're looking to confirm a release date when we hit the aforementioned beta milestone. However, it does look like we can make it this time and ship the game later this year. For the past several months, we've managed to meet every goal that we set for ourselves. Indeed, things are looking great!

Meanwhile, I’ll stick around updating, appreciating your patience, and answering questions. Let there be no doubt that we remain fully committed to this project and making sure it’s released as soon as humanly possible. And I can tell you this: it’s thrilling to finally see the script coming to life, which is working as we hoped, equal shares of horror and mystery that hopefully you won’t ever forget!

—Agustín

Even if this is a clusterfuck that's years behind it's intended release date, I did love Scratches enough to give this a whirl. So glad I didn't back it.

SerratedBiz

Arcane

- Joined

- Mar 4, 2009

- Messages

- 4,143

So did they give up on the idea of turning it into an episodic thing?

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 100,078

Another Halloween, another missed release target. There was an update earlier this month but it's more of the same.

Well it's got a couple of videos:

Did he do that livestream yesterday? I can't find any trace of it.

Boleskine

Arcane

- Joined

- Sep 12, 2013

- Messages

- 4,045

Another Halloween, another missed release target. There was an update earlier this month but it's more of the same.

Well it's got a couple of videos:

Did he do that livestream yesterday? I can't find any trace of it.

The part of the update that introduces one of those videos says

You may have seen this already as it went viral a few days ago.

I'm not sure 740 views qualifies for "going viral" but the visuals do look great. Time will tell if the years of delays and engine changes will be worth it.

The twitch page says the Oct 29 livestream was postponed for a few days, and they'll announce a new date soon.

fantadomat

Arcane

Just watched the video and thought "cool something new,would love to play it". Then i saw that it was 2012......yeah 200 rooms sounds too ambitious,should have made 20-50 rooms.

AdolfSatan

Arcane

- Joined

- Dec 27, 2017

- Messages

- 2,049

He's trying to get the Sorry Cop achievement.

SerratedBiz

Arcane

- Joined

- Mar 4, 2009

- Messages

- 4,143

Guy just keeps proving he can't be trusted with as much as a pet rock.

Ringhausen

Augur

- Joined

- Oct 12, 2010

- Messages

- 252

The only way this is getting done is if a right wing military hunta takes over production. That's the only way to get things done down there.

To put it into perspective these first person horror games have been released since the kickstarter in 2013:

To put it into perspective these first person horror games have been released since the kickstarter in 2013:

Plus countless shovelware. What have these guys produced over all this time? 2 engine shifts mid production and pipe dreams of 200 rooms.SOMA

Alien: Isolation

Resident Evil 7

Outlast

Outlast 2

Layers of Fear

Layers of Fear 2

Observer

Blair Witch

Call of Cthulhu

Boleskine

Arcane

- Joined

- Sep 12, 2013

- Messages

- 4,045

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/agustincordes/asylum-kickstart-the-horror/posts/2689706

Update #87

New Gameplay Video and Livestream!

Agustín Cordes

November 20, 2019

Hi, dear backers!

This is a brief update to show you our new gameplay video. A collection of greatly improved, familiar locations and new ones, focusing on interactions and things to do — including speaking with the mysterious denizens of the asylum! Take a look:

The game is working remarkably well. In fact, any stuttering you may notice in the video was our recording software behaving erratically

But, what you see here is 100% in-game stuff, no processing, no tricks. Asylum is running with a stable 60fps in fullscreen High quality on a 3-year old computer. It's even perfectly playable on Very High quality with extra sharp graphics!

So this is how the game looks and feels, and we hope you like it Just a tiny glimpse of many more locations you'll have to explore!

Demo update

We're very close to updating the exclusive backer demo! Absolutely everything you reported has been taking into account and we've reworked key game mechanics. We think you're going to be very happy with the improvements. It's all looking polished and snappy. Another bit of good news is that both macOS and Linux ports are finally working great

VIP backers will be glad to hear that we're expecting to upload more content beyond the 8:00 PM chapter mark before the end of the year. We can't wait to see what you think!

Livestream (confirmed)

I'm really sorry about this one. I should've posted more updates here. The promised livestream was postponed due to an incredibly nasty acute bronchitis I got a few weeks ago. It was sheer Hell And all because I didn't get a flu shot

Thankfully, I'm back in action and the livestream is totally happening this Friday 22 at 8:00 PM (UTC) on Twitch: https://www.twitch.tv/Senscape

If you can't make it, don't worry, I'll record everything. It would be great to see you there! I'll be happy to answer all your questions.

And that's it for today, but hopefully see you soon!

—Agustín

AdolfSatan

Arcane

- Joined

- Dec 27, 2017

- Messages

- 2,049

Jumped around, by changc landed on him saying:

"we think that we have... eh... about 8 to 10 months of remaning work, so potential release will be beginning... mid next year". Then catches himself by saying it might be so, no promises.

Some locations so ok, others . Main culprit seem to be poor choice of palette, texture, and lightning.

. Main culprit seem to be poor choice of palette, texture, and lightning.

"we think that we have... eh... about 8 to 10 months of remaning work, so potential release will be beginning... mid next year". Then catches himself by saying it might be so, no promises.

Some locations so ok, others

. Main culprit seem to be poor choice of palette, texture, and lightning.

. Main culprit seem to be poor choice of palette, texture, and lightning.

Last edited:

Boleskine

Arcane

- Joined

- Sep 12, 2013

- Messages

- 4,045

I watched the first few minutes of the livestream. He talks about the save game system, which is revolutionary in how it saves a screenshot of your last game state and also shows the calendar date you saved it.

Then I skipped to the last 10 minutes.

In two years the game will have been successfully ported to id Tech 7, the assets will be almost complete, and the vertical slice will be just a couple months away.

Then I skipped to the last 10 minutes.

- He hopes to finish the remaining rooms very quickly

- There are 8-10 months of work left.

- Major work left on 3 big cutscenes

- Wants to release a bigger chunk of the game to backers for testing

- Windows 7 support depends on Unreal engine updates

- Oldest supported MacOS: High Sierra

- Linux: "If Steam runs, Asylum should run in theory"

- Might release a public demo with preorder

- "Finally seeing the light at the end of the tunnel"

In two years the game will have been successfully ported to id Tech 7, the assets will be almost complete, and the vertical slice will be just a couple months away.

AdolfSatan

Arcane

- Joined

- Dec 27, 2017

- Messages

- 2,049

So, after eight years we finally got a demo with about... one puzzle. Yeah, I think that's it. Roughly 45' of gameplay.

On a positive note, the puzzle was nice and the atmosphere is well done (though I still think the texture work is botched).

With that being said, this still feels like a scam, almost a decade after the ks and all we've gotten is a short gameplay with missing features. It shows promise, and I'd like to believe the game will come thru, but... Yeah. Also, the performance is shit.

On a positive note, the puzzle was nice and the atmosphere is well done (though I still think the texture work is botched).

With that being said, this still feels like a scam, almost a decade after the ks and all we've gotten is a short gameplay with missing features. It shows promise, and I'd like to believe the game will come thru, but... Yeah. Also, the performance is shit.

People use the word scam too often; a scam implies there was never any plans to make a game, and that all fundraising efforts were to collect money for another purpose. Which absolutely isn't the case here; they always intended to make a game, and that game being Asylum. What happened here is a combination of project mis-management, feature creep, and over promises.... but it's never been a scam. I do think it's weird how people bandy about that term.

I don't exactly why it's taken them so long to develop, or what/how they spent their money, but I can assure you that this game has always been in production. It's just been mismanaged at points, for sure.

I don't exactly why it's taken them so long to develop, or what/how they spent their money, but I can assure you that this game has always been in production. It's just been mismanaged at points, for sure.

AdolfSatan

Arcane

- Joined

- Dec 27, 2017

- Messages

- 2,049

I stand corrected. The word scam was inappropriate, fiasco is more like it.

I was a backer of this project, but I've gave up on it a long ago. After several engine changes and program rewrites, this is all they show? Meh, I'll pass. I'll be pleasantly surprised if this game gets released (after Star Citizen), but until then, this is dead to me. A one man developer could have made this game with this timeframe.

Last edited:

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)