AdventureDex Review: The Magic Circle, an RPG without the "RPG" - or, On Games and "Notgames"

AdventureDex Review: The Magic Circle, an RPG without the "RPG" - or, On Games and "Notgames"

Review - posted by Crooked Bee on Mon 27 July 2015, 14:47:14

Tags: Question Games; The Magic CircleLooking Glass Studios was a unique game development wonder that went out too quickly. Instead of pursuing Doug Church's and Randy Smith's ambition of giving the player enough freedom and tools to "co-author" the game, the industry has taken a turn towards severely controlled (and controlling) AAA design, on one hand, and in an important sense no less restricted "notgames" or "walking simulators," on the other.

Made by a trio of ex-Ion Storm, Irrational Games and Arkane developers, The Magic Circle is a meta-game about the the past, present, and future of this thing called video games, which makes fun of those and other industry trends while digging deeply, but also humorously, into the tensions of the game development process and calling for a return to Looking Glass design principles.

That is what makes The Magic Circle's commentary on the industry so interesting, but also ultimately so old-fashioned and so, dare I say, aligned in an important way with RPG Codex's sensibilities. It is coming from a very specific design perspective, best encapsulated by terms like "player freedom" and "emergent" (or tool-based) gameplay. Putting you inside a Looking Glass Style-style first-person RPG with unfinished "RP" and "G" parts, The Magic Circle has you play the video game development equivalent of Wizardry IV's Werdna, half-forgotten, half-reviled, stripped of his powers, having his revenge on the "do-gooder" developers themselves and constructing his army of minions with in-game tools he discovers along the way.

I think the issues that The Magic Circle raises are generally important, and so this review, too, is "meta" in that it doubles as an essay on games and "notgames." I want to explain not only what The Magic Circle is like as a game, what it is trying to tell and do, and where it succeeds or fails, but also what "notgames" are and why, pretending to be a deconstruction of what makes a video game, they must be deconstructed themselves in order to go from notgames back (or rather, forward) to games -- a sensibility that, I believe, The Magic Circle exemplifies.

Have a snippet:

Read the full review: AdventureDex Review: The Magic Circle, an RPG without the "RPG" - or, On Games and "Notgames"

Made by a trio of ex-Ion Storm, Irrational Games and Arkane developers, The Magic Circle is a meta-game about the the past, present, and future of this thing called video games, which makes fun of those and other industry trends while digging deeply, but also humorously, into the tensions of the game development process and calling for a return to Looking Glass design principles.

That is what makes The Magic Circle's commentary on the industry so interesting, but also ultimately so old-fashioned and so, dare I say, aligned in an important way with RPG Codex's sensibilities. It is coming from a very specific design perspective, best encapsulated by terms like "player freedom" and "emergent" (or tool-based) gameplay. Putting you inside a Looking Glass Style-style first-person RPG with unfinished "RP" and "G" parts, The Magic Circle has you play the video game development equivalent of Wizardry IV's Werdna, half-forgotten, half-reviled, stripped of his powers, having his revenge on the "do-gooder" developers themselves and constructing his army of minions with in-game tools he discovers along the way.

I think the issues that The Magic Circle raises are generally important, and so this review, too, is "meta" in that it doubles as an essay on games and "notgames." I want to explain not only what The Magic Circle is like as a game, what it is trying to tell and do, and where it succeeds or fails, but also what "notgames" are and why, pretending to be a deconstruction of what makes a video game, they must be deconstructed themselves in order to go from notgames back (or rather, forward) to games -- a sensibility that, I believe, The Magic Circle exemplifies.

Have a snippet:

Notgames like Tale of Tales’ titles, Dear Esther, Journey, Kentucky Route Zero or Gone Home, also known derisively as “walking simulators,” attempt to subvert the expectations of what a video game is. To that end, they usually focus on the narrative, the atmosphere, and the player’s feelings in contrast to (the traditionally conceived notion of) player agency, exposing the latter’s limits as they have been internalized by the industry. Notgames are literally de-constructive, as they disassemble gameplay down to its basic components like walking around and triggering narrative or evocative events. For the most part, they present themselves as empathic experiences that purposefully avoid challenging the player, except emotionally. No matter how hard Adrian Chmielarz, the developer behind The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, criticizes Tale of Tales’ latest output, Sunset, his game is itself prefaced by “This is a narrative experience” – and indeed, has no gameplay “obstacles” to speak of. As such, it is perfectly in spirit of Michaël Samyn’s manifesto.

Now, deconstruction can be important to lay bare what makes a game. However – and here you can see that The Magic Circle has followed these developments closely – what if we start from that zero point and have the player re-construct gameplay instead? Given that notgames eschew challenge, this zero point can also incorporate the flip side of the same industry, AAA player convenience (quest markers, linearity, conveniently placed collectibles). In fact, I believe the term “notgame” can easily be extended to include the AAA side, too, as well as something like Telltale’s “experiences”. However, now that the industry has gone from games to notgames, what if we go in the opposite direction? After all, even if some or even most players are content with being stripped of their free will, what if there is one player who is not?

In asking these questions, and following them through in its gameplay, The Magic Circle breaks with the notgame design – and calls for a return to Looking Glass sensibilities. At first glance, the two have a common goal: doing away with things getting in the way of the player’s immersion. However, they approach it in conflicting ways. Gone Home’s developers may have been influenced by LGS, but The Magic Circle is at its polemical best in showing that notgames and Looking Glass-style games proceed in opposite directions. “Environmental storytelling” is by itself not enough. Notgames choose to outright ignore gameplay instead of reassessing the ways player freedom can be brought about or enabling interactive tool-focused design. By emphasizing obstacle-based exploration and emergent gameplay, The Magic Circle sides with games against notgames, even as it starts from the latter as its point of reference.

The Magic Circle is, in other words, a de-construction of a notgame and a re-construction of a game. At the same time, it is also aware of game development’s limits. A game with infinite player freedom may be impossible due to technical, financial, and time constraints, while a non-game stripped of the more complex forms of active agency is unsatisfactory – not to the developer maybe, but certainly to you, the odd player. Not coincidentally, it is precisely from a notgame that Old Pro sets you free – and it is another notgame that you disrupt under the guise of the E4 demo.

Now, deconstruction can be important to lay bare what makes a game. However – and here you can see that The Magic Circle has followed these developments closely – what if we start from that zero point and have the player re-construct gameplay instead? Given that notgames eschew challenge, this zero point can also incorporate the flip side of the same industry, AAA player convenience (quest markers, linearity, conveniently placed collectibles). In fact, I believe the term “notgame” can easily be extended to include the AAA side, too, as well as something like Telltale’s “experiences”. However, now that the industry has gone from games to notgames, what if we go in the opposite direction? After all, even if some or even most players are content with being stripped of their free will, what if there is one player who is not?

In asking these questions, and following them through in its gameplay, The Magic Circle breaks with the notgame design – and calls for a return to Looking Glass sensibilities. At first glance, the two have a common goal: doing away with things getting in the way of the player’s immersion. However, they approach it in conflicting ways. Gone Home’s developers may have been influenced by LGS, but The Magic Circle is at its polemical best in showing that notgames and Looking Glass-style games proceed in opposite directions. “Environmental storytelling” is by itself not enough. Notgames choose to outright ignore gameplay instead of reassessing the ways player freedom can be brought about or enabling interactive tool-focused design. By emphasizing obstacle-based exploration and emergent gameplay, The Magic Circle sides with games against notgames, even as it starts from the latter as its point of reference.

The Magic Circle is, in other words, a de-construction of a notgame and a re-construction of a game. At the same time, it is also aware of game development’s limits. A game with infinite player freedom may be impossible due to technical, financial, and time constraints, while a non-game stripped of the more complex forms of active agency is unsatisfactory – not to the developer maybe, but certainly to you, the odd player. Not coincidentally, it is precisely from a notgame that Old Pro sets you free – and it is another notgame that you disrupt under the guise of the E4 demo.

Read the full review: AdventureDex Review: The Magic Circle, an RPG without the "RPG" - or, On Games and "Notgames"

[Review by Crooked Bee]

Warning: This review contains some spoilers.

The Magic Circle is an RPG without the “RP” or “G”. To be more precise, it is an adventure-exploration game in which you find yourself inside a Looking Glass-style first-person RPG with unfinished “RP” and “G” parts. The RPG, also called The Magic Circle, has been in development for over twenty years, giving Cleve Blakemore’s Grimoire a run for its money. It was originally meant by its creator (Ish Gilder a.k.a. Starfather) to be a sci-fi System Shock-like game, but has become vaporware, not to mention the desperate switch of setting from sci-fi to fantasy. “Once proper RPG skills finally get implemented…,” dreams one team member, but the game makes it clear that this will never be the case. The Starfather has gone sterile, the development team has gone crazy – and they are now your antagonists. You, on your part, come in just when the team is hastily throwing together an E4 demo, completely unrepresentative of the state of the game. You are a play-tester of sorts – though where exactly you come from is actually a major, if optional, plot point – who must now re-construct the game from point zero by hacking into the objects and creatures you encounter and restoring cut content.

It was the unattainable dream of chasing a perfect game, coupled with the team’s in-fighting, that got development into this sorry state, and it is now up to you to somehow sort out this mess of truly industrial proportions – to figure out the game’s, the team’s, and even the game industry’s backstory and to disrupt the antagonists’ not so much malevolent as too idealistic plans. In that, you are assisted only by an in-game character by the name of “Old Pro.” You enter the game world at a point at which you can only walk around it and re-write some of its basic behavior, and then slowly build up your powers by manipulating it in creative ways that the developers, whom Old Pro refers to as “the gods,” never intended in their desire to control the player instead of giving her tools. “What does it mean for a game to be perfectly finished?” and “What does one player matter?” are both questions that The Magic Circle asks.

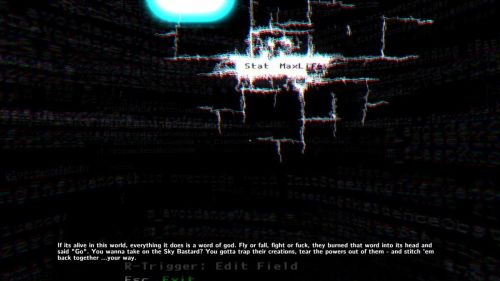

“If it’s alive in this world, everything it does is a word of god. Fly or fall, fight or fuck, they burned that word into its head and said ‘Go.’” – Old Pro

By now, you should have discerned the game’s pedigree. Jordan Thomas, Kain Shin, and Stephen Alexander, making up a studio called Question, come from Ion Storm, Irrational Games, and Arkane, sharing what is ultimately the Looking Glass Studios design philosophy. That is what makes The Magic Circle's commentary on the industry so interesting, but also ultimately so old-fashioned and so, dare I say, aligned in an important way with RPG Codex's sensibilities. It is coming from a very specific design perspective, best encapsulated by terms like “player freedom” and “emergent” (or tool-based) gameplay, associated with the names of Doug Church, Randy Smith, Harvey Smith, and Warren Spector.

In light of that, it comes as no surprise that The Magic Circle builds on the industry trends, new and old – “notgames”, walking simulators, linear corridor exploration, pointless collectibles, quest markers, auteur-developer cults, etc. – in order to subvert them, and not just in its writing, but most importantly in its gameplay. The Magic Circle is a meta-game, an interactive commentary on the industry, targeted mainly at fellow game developers or those interested in playing through a critique of the history, current state, and future of this thing called video games.

The Magic Circle is fairly short. It may be broadly divided into three parts or acts, of which the first, the Overworld, is the longest (up to six hours long if you are a completionist like me). The second is merely a brief, exposition-heavy sequence building on the first and taking place during the E4 demo, and the third is a mini-game of sorts, detached gameplay-wise (but also, I believe, in its writing and characterization) from the others. In what follows, I will focus on the Overworld, since it represents the bulk and core of the game, before voicing my dissatisfaction with the third act as well as pointing out where the game as a whole falls short.

Mechanics

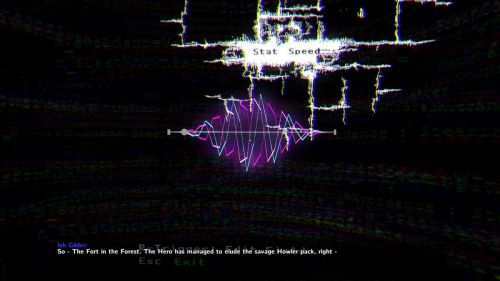

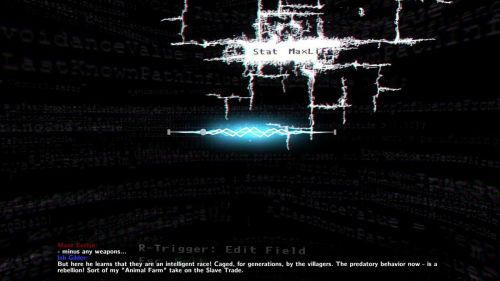

The “minus any systems” point is precisely where the game begins, as Ish Gilder dramatically recounts the generic fantasy premise he came up with, no doubt during the LARPing parties at his castle (mentioned in the game). When starting out, you, as a play-tester, cannot do anything but move around, trigger an occasional scripted event, and listen to developer comments. As the player, you are unimportant, or worse, the enemy; after all, it is only the developers’ big ideas that matter. Even your sword, obtained in one of the scripted events, is immediately taken away in order to make the game more family-friendly – leaving you weaponless inside what looks like a toothless game. If The Magic Circle were to stop at that, however, it would be simply one of those “walking simulators” populating the market. Instead, you run into a bug and die, at which point the enigmatic Old Pro comes to your rescue and, in secret from the development team, helps you break free from developer control – in terms of both mechanics and exploration.

In The Magic Circle, you explore the (mostly placeholder) world created by the development team, but you do not interact with the developers except passively, when one of them notices and talks to you. You only interact with the game, trying to construct the “systems” from the scant bits of code you can access. As a mere tester, you cannot implement the missing RPG part even if you wanted to. With Old Pro’s help, however, you are given the power to work with what is already there – to restore cut content, uncovering the earlier sci-fi version of the game, and to hack into the creature and object behavior code. To make things less complicated, The Magic Circle gives you access to the code not as code proper, but as a set of names, abilities, and behaviors, all of which you can edit or store in your inventory and then transfer to any other editable creature or object. You cannot transfer these powers to yourself, though, only to your re-programmed minions – like this:

This vaguely dog-like creature wants to kill me, but I can freeze and edit it instead.

I can change its name, as well as strip it of its movement – and its teeth.

I can leave it behind, make it attack its own kind, or simply follow me. Looks like I have a guard dog now.

I can also extract the Fireproof ability from the nearby rock – and put it onto Howdy. This is not just a gimmick either, as it can make your life much easier at one point later in the game.

In The Magic Circle, you are Wizardry IV’s Werdna, half-reviled, half-forgotten, stripped of your powers, yet intent on having your revenge with the help of the monsters you recruit. Collecting names, attack types, and special abilities, so as to use them in creative ways, is what the game’s mechanics are about. At one point, your “companions” may include an explosive ball of flame that you’d better steer clear of yourself, a zombie with a railgun, a giant mushroom wizard, a lightning bolt-casting rat, a worm infecting those who attack it, a mini-satellite dish with a tracker beam, and a flying turtle-like creature that carries you on its back, all of them fireproof – the specifics being entirely in your power, and the number of followers only limited by the amount of behaviors in your inventory. For each follower, you can specify its special properties, its movement (ground, hovering, flying) and attack (from melee to different kinds of ranged) type, teach it to regard a specific creature as an enemy, as well as upgrade its stats.

“I guess you were supposed to live out a fairytale – born to end some war when your sword got big enough. But the gods woulda had to agree on all your powers, so – you get none. But look around – every creature here was abandoned by the gods. Let them be your fists… your fangs.” – Old Pro to the player

My small but powerful (and highly customizable) army.

One eureka moment of the game for me was realizing I could extract a very useful ability from a seemingly non-interactive object that would let me use my minions to access places I normaly would not be able to. Another involved getting killed on purpose to discover a special property I could not even reach otherwise, in turn allowing me to best a seemingly invincible foe. Not all creatures can be easily edited either, so that you might have to defeat (or, in the game’s terminology, “ghost”) them first – which necessitates discovering the means to do so in the first place. Many of these moments are entirely optional, too. The game gives you tools, but how you utilize them, and even to what extent you explore them, is up to you. There was this one ability that I never figured out how to use, although it sounded very intriguing.

Exploration

Contrary to Michaël Samyn’s urging, The Magic Circle is all about obstacles – mostly in-game, but not exclusively.

Editing your pets to have crazy, non-obvious properties and powers can be entertaining, but The Magic Circle’s plea for player freedom and emergence manifests itself not only in the tools it gives you, but also in the way these tools are tied in with exploration. The moment Old Pro sets you free from the god-like developers’ pesky intervention is also the moment starting from which you can explore the world freely – including places you do not have the “permission” from “the gods” to access. New attack types and special abilities must be uncovered through exploration, and not all of this exploration is obvious. Many of the nooks and crannies are facultative. Some of them can be accessed simply by straying off the beaten path, but others require you to rely on the tools you discover all around the game world to be reached. Some of the tools you obtain can be unnecessary (The Magic Circle is not afraid of redundant tools), but others, like the ability to fly, mark a turning point in the first part of the game.

To be clear: The Magic Circle is not a “puzzler.” What may be called “puzzles” here, are rather ways of overcoming obstacles as you explore the world and your collection of tools naturally grows. The tools are there to help you get past those. In the first (best and largest) part of the game, you are given one simple task – getting to the character whom Old Pro dubs the “Sky Bastard,” hovering over a far away platform, seemingly out of reach, and protected by three helicopter-like minions. The game never spells out how exactly you are supposed to reach it. Similarly, if you see a tough monster or a chasm you cannot cross, that means you should come back later with better tools. Almost nothing of that is telegraphed. You see a tool? You can use it anywhere. In line with the design philosophy underlying the game, no obstacle has the “perfect” solution – or at least that is the idea, which often works. Given, however, that this is an indie game with limited scope and budget, your freedom is not unlimited and I wish the tools were more numerous.

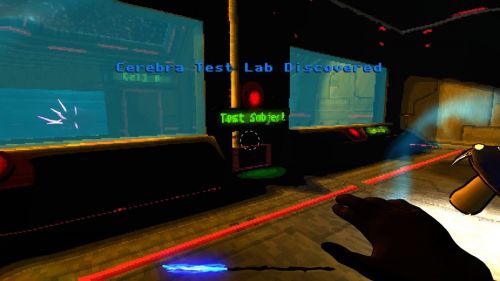

Similarly, Cerebra Lab – and figuring out how to kill and edit Cerebra (the glowing creature in the back) – is not required to proceed. Not to mention determining what to use its special ability for.

The Magic Circle is a short game. Even if you take your time, it will not last you more than six to eight hours. I recommend against rushing through it, though, since a lot of the backstory, and much of its commentary, is hidden off the beaten path. (And if you are not interested in these, there is little point in playing the game anyway.) As you explore, you come across developer notes. Most of these are flavor, but some play a crucial role in figuring out the background of what is going on. Aside from those, there are also audio logs – an obvious System Shock homage – with bits and pieces of conversations among the development team, or Ish Gilder’s solo, authorial commentary. Well-written, they help flesh out the characters and add a touch of comedy to what is otherwise presented as the grim and torturous process of developing a complete, shippable game, hindered by too many things – from tiny bugs and code limitations to the development team’s irreconcilable design goals or their despair over the inability to ever finish the damn thing.

The Magic Circle

The characters themselves are an odd, but also familiar, bunch. Ish “Starfather” Gilder, the project lead, is a cross between Richard Garriott (Lord Brit-Ish) and Peter Molyneux; megalomaniacal, brilliant, lost in his own world. He is obsessed with outer space and hosts ridiculous LARPing parties (“orgies,” as another character suggests) at his castle. To drive the point home, the penultimate part of the game also seems to be a play on the famous episode of killing Lord British during Ultima Online’s 1997 beta test. Emphasizing the longevity of his career, the game has him reminisce about what I take to be a reference to the 1980s “anything goes” sort of creative freedom: “Back then I just wrote… whatever I wanted you to imagine, and was shocked when you paid me so well.”

Sometimes, Ish Gilder’s obsession with story can take him in a parodic “social tolerance” direction.

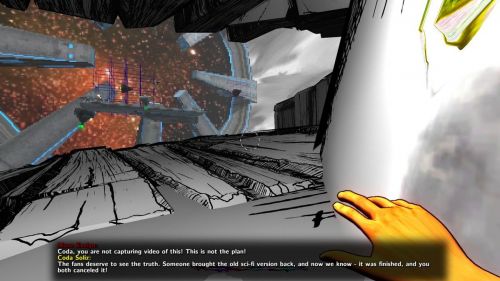

At the same time, Ish also cares deeply about the game and even takes a home-equity loan to fund its development. Having been in the industry since the 1980s, however, it is unclear if he still has what it takes to deliver the perfect game that his fans faithfully – but ever more impatiently – expect. This dormant yet potentially explosive clash between fan demands and developer illusions is one of the game’s leitmotifs, reaching its climax in the second act, but also finding its embodiment in another major antagonist, Coda Soliz, an intern, a streamer, and a devoted Ish Gilder fan – with a twist I will not spoil. Suffice it to say, Coda comes from within the fan community and retains her ties to it. She also subscribes to the “by gamers, for gamers” motto perhaps a little too literally.

Then there is Old Pro, the “anti-hero,” as he is called by Ish, communicating with you through weird talking stone heads you discover around the world. His “anti,” however, is not “BioWare evil” – it is a Promethean rebelliousness of an in-game character gone rogue, the impulse to rip control of what he perceives to be his world from the gods’ hands and take it for himself, to disrupt the pre-programmed world.

Ish, Coda, and even Old Pro are similar, in that each lives inside a very limited “circle” of reality, which they regard as the sole truth, incapable of seeing the vanity of clinging to their narrow standpoint. As Old Pro himself succintly puts it, “People don’t arc. They loop.”

“The gods’ve promised that they’ll tie off this story in a neat little bow. Everyone will confront a “demon,” learn a hard-won lesson, and complete an “arc.” But that’s a crock – watch ‘em long enough and you’ll see. People don’t arc. They loop.” – Old Pro

Not just people, though. This kind of loop, not arc, is characteristic of the game’s development going in circles, as well as the industry itself. Do we discard a System Shock in favor of a generic fantasy RPG that, however, we can probably ship? Old Pro is understandably irritated at that: “I had this world near to fixed, despite the gods. Then they scrap the whole damn thing and start over with the Magic Frickin’ Kingdom up there.” The important question is, however, what do we discard next? Player agency?

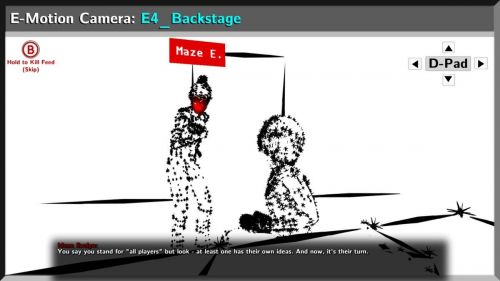

Ish Gilder’s sci-fi game was supposed to be a tale of the Space Station LIMINA (liminal: relating to a transitional or initial stage of a process) “and its fateful encounter with the circle.” The “magic circle” is apparently developer lingo for the self-enclosed illusion that a video game creates, into which you escape from the heat death of the universe – only to “come back dead, but wearing this beatific grin.” It is, however, also the aforementioned loop. Similarly to Coda, Maze Evelyn, the third key member of the team, used to be an intern and a gamer. She also pushed for adding multiplayer to the game – the sort of player-driven experience that was regarded as a panacea not so long ago. (Old Pro: “In my day, the gods were cocky. Figured they could handle more than one Hero.”) Now though, she simply wants out of the endless circle. In this, she is sort of on your side.

Maze cannot get out, though, due to contractual obligations. Neither can Ish, with his grand ideas and his home-equity loan, or Coda with her different, if no less feverish idea of what a perfect game involves. The finale of Coda’s storyline in parts one and two of the game (leaving the third act aside for now) loops back to Maze’s multiplayer obsession and exposes its destructive aspect. At the same time, Coda views Maze’s desire to escape as betrayal (“Maze Evelyn, you rose from the fan community, but you have forgotten us! And before we fire you: you will atone!”). True to the musical meaning of her name, Coda makes a final attempt to enact the closure of the circle. Turns out, it is not just harder than it sounds – the circle is porous, and the “real world” is not completely separate from what is inside. Whereas Ish and Maze can provoke sympathy, Coda hardly ever does, especially as she is shown rallying the mob at one point in the game. Fans, too, are shown to be aggressive – and then bored. We may sympathize with Ish, but they do not.

“I see every punchline coming, I smirk at the idea of a joke. This ain’t about pity – a god oughta take some joy in his work.” – Old Pro on the gods that failed

That is not all there is to the story, though. Coda may be a parody of nostalgic fans, but her one-sidedness serves to shed light on how old, impotent – and stuck in a loop that is dragging him down – Ish Gilder himself has become (“Wow – how old is this stuff? My god… it’s… years. I’ll be sixty-one in the fall, Coda. No family. For better or worse this – is what they’ll remember me by”). Game development is tiring. Looping is extremely tiring, too. As a consequence, the temptation is to do away with perfection or maybe even abandon the “gameplay” part because let’s be honest: it requires so much work.

From Notgames (Forward) to Games

The Magic Circle references almost the entire history of game development. Allusions to different periods and gameplay styles abound, some direct, others more subtle. The 1980s play a role, the 1990s are featured prominently, but so is the present day – the epoch of player convenience on one hand (from quest markers to corridor design) and “notgames” on the other.

Notgames like Tale of Tales’ titles, Dear Esther, Journey, Kentucky Route Zero or Gone Home, also known derisively as “walking simulators,” attempt to subvert the expectations of what a video game is. To that end, they usually focus on the narrative, the atmosphere, and the player’s feelings in contrast to (the traditionally conceived notion of) player agency, exposing the latter’s limits as they have been internalized by the industry. Notgames are literally de-constructive, as they disassemble gameplay down to its basic components like walking around and triggering narrative or evocative events. For the most part, they present themselves as empathic experiences that purposefully avoid challenging the player, except emotionally. No matter how hard Adrian Chmielarz, the developer behind The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, criticizes Tale of Tales’ latest output, Sunset, his game is itself prefaced by “This is a narrative experience” – and indeed, has no gameplay “obstacles” to speak of. As such, it is perfectly in spirit of Michaël Samyn’s manifesto.

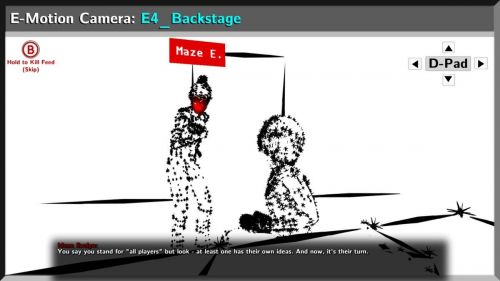

“You say you stand for ‘all players’ but look – at least one has their own ideas. And now, it’s their turn.” – Maze Evelyn, talking to Coda about the protagonist

Now, deconstruction can be important to lay bare what makes a game. However – and here you can see that The Magic Circle has followed these developments closely – what if we start from that zero point and have the player re-construct gameplay instead? Given that notgames eschew challenge, this zero point can also incorporate the flip side of the same industry, AAA player convenience (quest markers, linearity, conveniently placed collectibles). In fact, I believe the term “notgame” can easily be extended to include the AAA side, too, as well as something like Telltale’s “experiences”. However, now that the industry has gone from games to notgames, what if we go in the opposite direction? After all, even if some or even most players are content with being stripped of their free will, what if there is one player who is not?

In asking these questions, and following them through in its gameplay, The Magic Circle breaks with the notgame design – and calls for a return to Looking Glass sensibilities. At first glance, the two have a common goal: doing away with things getting in the way of the player’s immersion. However, they approach it in conflicting ways. Gone Home’s developers may have been influenced by LGS, but The Magic Circle is at its polemical best in showing that notgames and Looking Glass-style games proceed in opposite directions. “Environmental storytelling” is by itself not enough. Notgames choose to outright ignore gameplay instead of reassessing the ways player freedom can be brought about or enabling interactive tool-focused design. By emphasizing obstacle-based exploration and emergent gameplay, The Magic Circle sides with games against notgames, even as it starts from the latter as its point of reference.

The Magic Circle is, in other words, a de-construction of a notgame and a re-construction of a game. At the same time, it is also aware of game development’s limits. A game with infinite player freedom may be impossible due to technical, financial, and time constraints, while a non-game stripped of the more complex forms of active agency is unsatisfactory – not to the developer maybe, but certainly to you, the odd player. Not coincidentally, it is precisely from a notgame that Old Pro sets you free – and it is another notgame that you disrupt under the guise of the E4 demo.

“The gods can’t predict you. So they … invoke you to win an argument, like you’re an evil spirit.” – Old Pro to the player

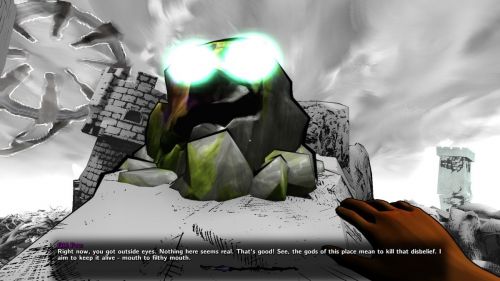

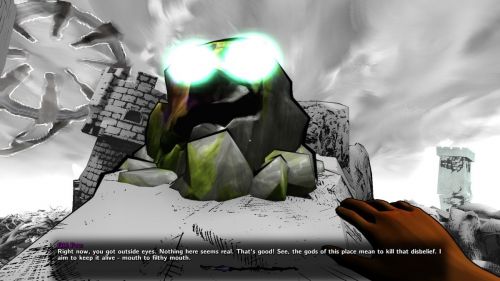

“Nothing here seems real. That’s good! See, the gods of this place mean to kill that disbelief. I aim to keep it alive.” – Old Pro

In all that, The Magic Circle is very old-fashioned. As it happens, the way forward is by picking up a thread that was lost and buried, just like Space Station LIMINA underneath the Magical Mushroom Kingdom. Not in order to be stuck in the past like Old Pro, of course, but precisely to move forward.

That is not to say that The Magic Circle embraces player agency unreservedly, either. It has enough critical sense to see its limitations and perils. Old Pro and Coda both show, in different ways, that giving full control to the player is not always well-advised. Some of the commentary implies that Looking Glass’ goal of endless emergence and interactivity is utopian. Having the player fully (co-)author the game, of which Doug Church and Randy Smith dreamed, is impossible unless, ironically, the game’s A.I. itself were evolving – unless the player were, in a sense, the game’s A.I. As one of the characters puts it, “What would I even say?? The game woke up and tried to ship itself?” – the humorous mirror image of the developers trying to control every player action.

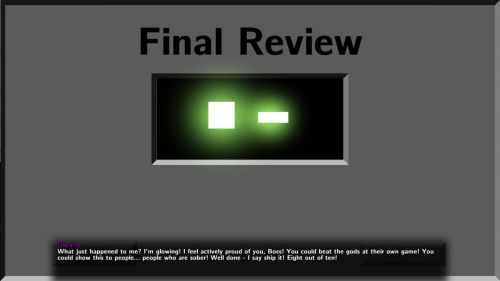

It is in that context that I find the third, final part of the game unsatisfactory. For reasons I will leave for you to discover, it has you construct a short dungeon crawler game of your own with extremely limited tools, which then gets reviewed by fictive game press. To cut a long story short, you build a generic dungeon crawl and get “8/10” reviews for it. The gameplay in this part is not just different – it gets disappointingly simplistic. Gone is the exploration. Gone are both player freedom and learning or experimenting with new tools. Thematically, too, whereas the first two parts, the Overworld and the E4 demo, are all about obstacles on the ambitious way to a perfect game, to player and developer freedom, the third part makes you simply give up all ambition altogether. If a linear hack’n’slash dungeon crawler is good enough to be shipped and positively reviewed, then why bother with something complex? This may not be thematic inconstency as such – after all, one could argue that this kind of ending is fitting in a way – but it is, I believe, thematic reductionism.

It is when it comes to characterization that I found act three to be at its most inconsistent with the rest of the game. Given their design sensibilities in parts one and two, you would think Old Pro and Coda should be disappointed by the kind of linear, non-interactive game you are building here. Instead, they give up all talk of player agency and cheer as you pick up a health potion or slay a monster in two simple swings, or get bored if there is no uninterrupted action to keep them entertained, all the while delivering some of the game’s most cringeworthy lines. In all that, depending on how you interpret this abrupt change, The Magic Circle either gets too “meta” for its own good or oversimplifies the main points of the first two acts – no matter if you take the third act to be a pessimistic take on where the industry is headed, a commentary on instant gratification and the ineptness of game journalism, or a triumphalist pandering to the industry and the press, which got lambasted in acts one and two. Even if the message of the third act is supposed to be that everything in the industry falls back into place on its circular course, it should not, I believe, have been so reductionist in its gameplay and writing.

Conclusion

The Magic Circle is a gameplay-focused commentary on the industry, with a clever premise, creative exploration and puzzle- (or rather, obstacle-)solving, and some genuinely fun, and funny, parts. However, I find that it ultimately fails as a “stand-alone” game, even if it does so in an interesting way. It is essentially an interactive critique. For those unfamiliar with the Looking Glass legacy or who do not understand what this style of design is about, too much of The Magic Circle’s message – and even the cleverness of its gameplay – is bound to fall flat.

Partly as a result of acts two and three being so divorced from the first, The Magic Circle never lives up to the full potential of its gameplay. The size and freedom of the Overworld, the number of powers and special properties, and the amount of content as a whole, fall just short of what would be required for it to stand on its own. The Magic Circle itself is aware of that, with some of the characters commenting on the limits of the game’s budget and scope, but again, while fine for a commentary, and while it purposefully distances itself from any pretense of completeness or perfection, it is a shame that the first, most free-form part of the game ends just as you have gotten comfortable with the tools and the second and third fail to offer a comparable degree of freedom or sophistication.

The commentary itself is mostly fine, and to the point. The industry is plagued by development hell, poor ideas, ambitious ideas that cannot be realized, corridor design and lack of player agency, developers who consider themselves to be gods but are in fact control freaks distrusting the player, as well as obsessed fans who mirror those developers in their own perverted way. Aimed at people addicted to the “game” part of video games, The Magic Circle ultimately cautions you against taking video games too seriously – which is what everyone from Ish to Coda to Old Pro does, with fatal consequences. Whenever the commentary may not be quite on point, it leaves enough room for ambiguity to make up for that. The ending sequence was, however, a let-down to me.

“He told the first story – and ruined the first game with it.” – Maze Evelyn on the origin of games

For all its problems, though, it is refreshing that The Magic Circle emphasizes gameplay to this degree. Even if, for various reasons, it effectively remains stuck between a game and a notgame, it does demonstrate one thing convincingly: notgames may be a fact, a fad or an inspiration, but at this point, we need to move beyond them. A de-construction is not an end in itself; its purpose is to be followed by a re-construction. Inside the world of The Magic Circle, developers are incapable of that. Whether the industry at large is, remains to be seen.

The Magic Circle is available on Steam. I am grateful to Infinitron, felipepepe, and sser for their feedback and suggestions on an earlier version of this article.

Warning: This review contains some spoilers.

“…it’s disappointing how many videogames cling to obstacle-based designs. As if players have to earn the privilege to explore by passing an irrelevant test. Now is the time to open up this medium, to let go of our affections and addictions, of our loyalty to childhood memories, to open up the beauty of videogames for the world to see.”

– Michaël Samyn, Tale of Tales, http://notgames.org/blog/

“Our desire to create traditional narrative and exercise authorial control over the gaming world often inhibits the player's ability to involve themselves in the game world.”

– Doug Church, Looking Glass Studios, “Abdicating Authorship,” GDC 2000

The Magic Circle is an RPG without the “RP” or “G”. To be more precise, it is an adventure-exploration game in which you find yourself inside a Looking Glass-style first-person RPG with unfinished “RP” and “G” parts. The RPG, also called The Magic Circle, has been in development for over twenty years, giving Cleve Blakemore’s Grimoire a run for its money. It was originally meant by its creator (Ish Gilder a.k.a. Starfather) to be a sci-fi System Shock-like game, but has become vaporware, not to mention the desperate switch of setting from sci-fi to fantasy. “Once proper RPG skills finally get implemented…,” dreams one team member, but the game makes it clear that this will never be the case. The Starfather has gone sterile, the development team has gone crazy – and they are now your antagonists. You, on your part, come in just when the team is hastily throwing together an E4 demo, completely unrepresentative of the state of the game. You are a play-tester of sorts – though where exactly you come from is actually a major, if optional, plot point – who must now re-construct the game from point zero by hacking into the objects and creatures you encounter and restoring cut content.

It was the unattainable dream of chasing a perfect game, coupled with the team’s in-fighting, that got development into this sorry state, and it is now up to you to somehow sort out this mess of truly industrial proportions – to figure out the game’s, the team’s, and even the game industry’s backstory and to disrupt the antagonists’ not so much malevolent as too idealistic plans. In that, you are assisted only by an in-game character by the name of “Old Pro.” You enter the game world at a point at which you can only walk around it and re-write some of its basic behavior, and then slowly build up your powers by manipulating it in creative ways that the developers, whom Old Pro refers to as “the gods,” never intended in their desire to control the player instead of giving her tools. “What does it mean for a game to be perfectly finished?” and “What does one player matter?” are both questions that The Magic Circle asks.

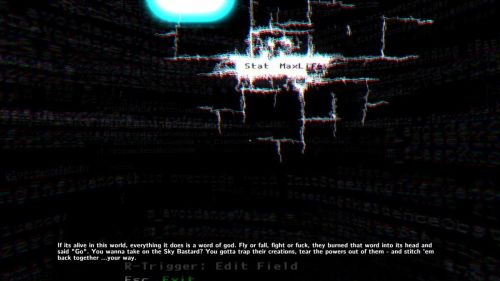

“If it’s alive in this world, everything it does is a word of god. Fly or fall, fight or fuck, they burned that word into its head and said ‘Go.’” – Old Pro

By now, you should have discerned the game’s pedigree. Jordan Thomas, Kain Shin, and Stephen Alexander, making up a studio called Question, come from Ion Storm, Irrational Games, and Arkane, sharing what is ultimately the Looking Glass Studios design philosophy. That is what makes The Magic Circle's commentary on the industry so interesting, but also ultimately so old-fashioned and so, dare I say, aligned in an important way with RPG Codex's sensibilities. It is coming from a very specific design perspective, best encapsulated by terms like “player freedom” and “emergent” (or tool-based) gameplay, associated with the names of Doug Church, Randy Smith, Harvey Smith, and Warren Spector.

In light of that, it comes as no surprise that The Magic Circle builds on the industry trends, new and old – “notgames”, walking simulators, linear corridor exploration, pointless collectibles, quest markers, auteur-developer cults, etc. – in order to subvert them, and not just in its writing, but most importantly in its gameplay. The Magic Circle is a meta-game, an interactive commentary on the industry, targeted mainly at fellow game developers or those interested in playing through a critique of the history, current state, and future of this thing called video games.

The Magic Circle is fairly short. It may be broadly divided into three parts or acts, of which the first, the Overworld, is the longest (up to six hours long if you are a completionist like me). The second is merely a brief, exposition-heavy sequence building on the first and taking place during the E4 demo, and the third is a mini-game of sorts, detached gameplay-wise (but also, I believe, in its writing and characterization) from the others. In what follows, I will focus on the Overworld, since it represents the bulk and core of the game, before voicing my dissatisfaction with the third act as well as pointing out where the game as a whole falls short.

Mechanics

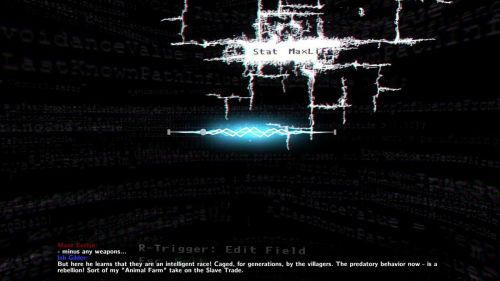

“I feel compelled to reward you somehow, but minus any systems, all that’s left is (sighing) story.”

– Maze Evelyn to the player

The “minus any systems” point is precisely where the game begins, as Ish Gilder dramatically recounts the generic fantasy premise he came up with, no doubt during the LARPing parties at his castle (mentioned in the game). When starting out, you, as a play-tester, cannot do anything but move around, trigger an occasional scripted event, and listen to developer comments. As the player, you are unimportant, or worse, the enemy; after all, it is only the developers’ big ideas that matter. Even your sword, obtained in one of the scripted events, is immediately taken away in order to make the game more family-friendly – leaving you weaponless inside what looks like a toothless game. If The Magic Circle were to stop at that, however, it would be simply one of those “walking simulators” populating the market. Instead, you run into a bug and die, at which point the enigmatic Old Pro comes to your rescue and, in secret from the development team, helps you break free from developer control – in terms of both mechanics and exploration.

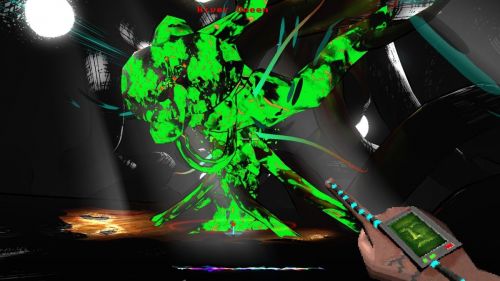

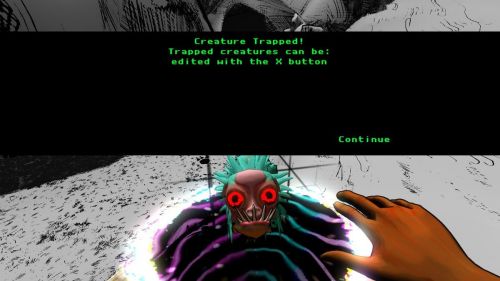

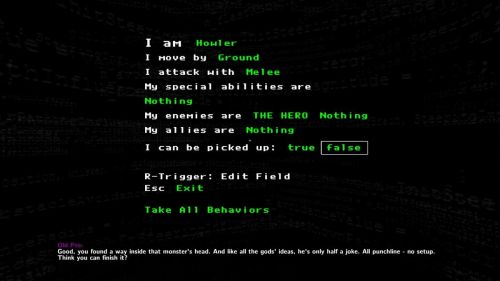

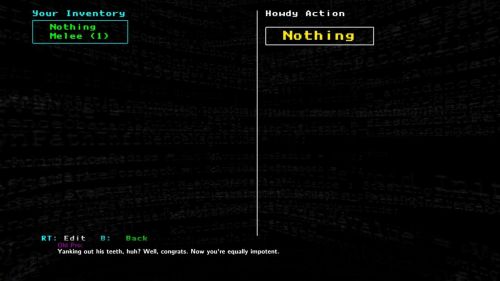

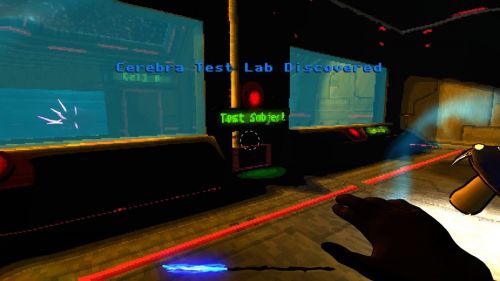

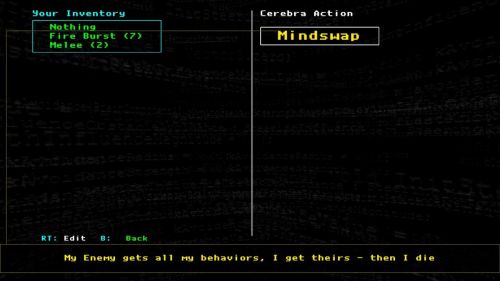

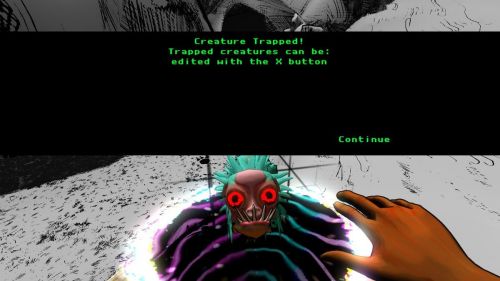

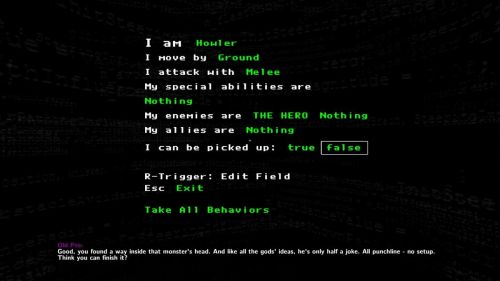

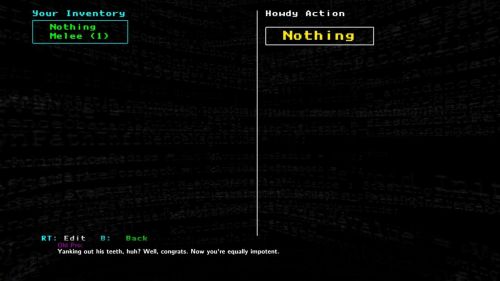

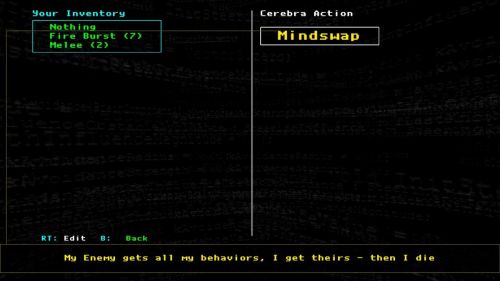

In The Magic Circle, you explore the (mostly placeholder) world created by the development team, but you do not interact with the developers except passively, when one of them notices and talks to you. You only interact with the game, trying to construct the “systems” from the scant bits of code you can access. As a mere tester, you cannot implement the missing RPG part even if you wanted to. With Old Pro’s help, however, you are given the power to work with what is already there – to restore cut content, uncovering the earlier sci-fi version of the game, and to hack into the creature and object behavior code. To make things less complicated, The Magic Circle gives you access to the code not as code proper, but as a set of names, abilities, and behaviors, all of which you can edit or store in your inventory and then transfer to any other editable creature or object. You cannot transfer these powers to yourself, though, only to your re-programmed minions – like this:

This vaguely dog-like creature wants to kill me, but I can freeze and edit it instead.

I can change its name, as well as strip it of its movement – and its teeth.

I can leave it behind, make it attack its own kind, or simply follow me. Looks like I have a guard dog now.

I can also extract the Fireproof ability from the nearby rock – and put it onto Howdy. This is not just a gimmick either, as it can make your life much easier at one point later in the game.

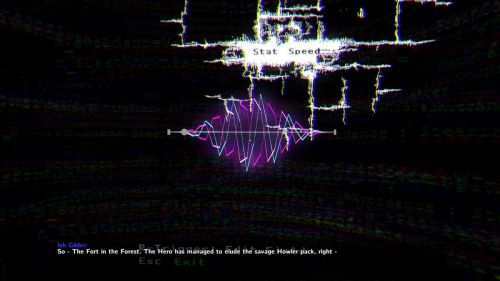

In The Magic Circle, you are Wizardry IV’s Werdna, half-reviled, half-forgotten, stripped of your powers, yet intent on having your revenge with the help of the monsters you recruit. Collecting names, attack types, and special abilities, so as to use them in creative ways, is what the game’s mechanics are about. At one point, your “companions” may include an explosive ball of flame that you’d better steer clear of yourself, a zombie with a railgun, a giant mushroom wizard, a lightning bolt-casting rat, a worm infecting those who attack it, a mini-satellite dish with a tracker beam, and a flying turtle-like creature that carries you on its back, all of them fireproof – the specifics being entirely in your power, and the number of followers only limited by the amount of behaviors in your inventory. For each follower, you can specify its special properties, its movement (ground, hovering, flying) and attack (from melee to different kinds of ranged) type, teach it to regard a specific creature as an enemy, as well as upgrade its stats.

“I guess you were supposed to live out a fairytale – born to end some war when your sword got big enough. But the gods woulda had to agree on all your powers, so – you get none. But look around – every creature here was abandoned by the gods. Let them be your fists… your fangs.” – Old Pro to the player

My small but powerful (and highly customizable) army.

One eureka moment of the game for me was realizing I could extract a very useful ability from a seemingly non-interactive object that would let me use my minions to access places I normaly would not be able to. Another involved getting killed on purpose to discover a special property I could not even reach otherwise, in turn allowing me to best a seemingly invincible foe. Not all creatures can be easily edited either, so that you might have to defeat (or, in the game’s terminology, “ghost”) them first – which necessitates discovering the means to do so in the first place. Many of these moments are entirely optional, too. The game gives you tools, but how you utilize them, and even to what extent you explore them, is up to you. There was this one ability that I never figured out how to use, although it sounded very intriguing.

Exploration

“Now, boss – maybe you see a problem, and your solution doesn’t seem “clean” enough. Like maybe the gods wanted you to do something else. Something “perfect.” Fuck. That. Chasing perfect is what got them into this mess. If your way does the job – it’s more right than they’ll ever be.”

– Old Pro, talking about “the gods” and the player

“See, if creation is a language – you wanna be the slang. Take what the gods made and… give it a filthy new truth.”

– Old Pro

Contrary to Michaël Samyn’s urging, The Magic Circle is all about obstacles – mostly in-game, but not exclusively.

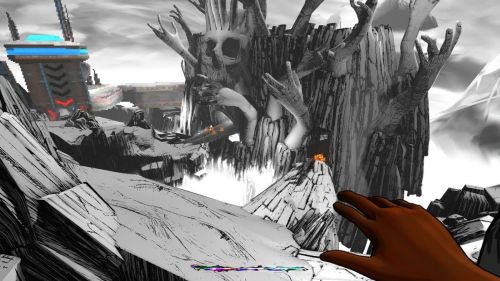

Editing your pets to have crazy, non-obvious properties and powers can be entertaining, but The Magic Circle’s plea for player freedom and emergence manifests itself not only in the tools it gives you, but also in the way these tools are tied in with exploration. The moment Old Pro sets you free from the god-like developers’ pesky intervention is also the moment starting from which you can explore the world freely – including places you do not have the “permission” from “the gods” to access. New attack types and special abilities must be uncovered through exploration, and not all of this exploration is obvious. Many of the nooks and crannies are facultative. Some of them can be accessed simply by straying off the beaten path, but others require you to rely on the tools you discover all around the game world to be reached. Some of the tools you obtain can be unnecessary (The Magic Circle is not afraid of redundant tools), but others, like the ability to fly, mark a turning point in the first part of the game.

To be clear: The Magic Circle is not a “puzzler.” What may be called “puzzles” here, are rather ways of overcoming obstacles as you explore the world and your collection of tools naturally grows. The tools are there to help you get past those. In the first (best and largest) part of the game, you are given one simple task – getting to the character whom Old Pro dubs the “Sky Bastard,” hovering over a far away platform, seemingly out of reach, and protected by three helicopter-like minions. The game never spells out how exactly you are supposed to reach it. Similarly, if you see a tough monster or a chasm you cannot cross, that means you should come back later with better tools. Almost nothing of that is telegraphed. You see a tool? You can use it anywhere. In line with the design philosophy underlying the game, no obstacle has the “perfect” solution – or at least that is the idea, which often works. Given, however, that this is an indie game with limited scope and budget, your freedom is not unlimited and I wish the tools were more numerous.

Similarly, Cerebra Lab – and figuring out how to kill and edit Cerebra (the glowing creature in the back) – is not required to proceed. Not to mention determining what to use its special ability for.

The Magic Circle is a short game. Even if you take your time, it will not last you more than six to eight hours. I recommend against rushing through it, though, since a lot of the backstory, and much of its commentary, is hidden off the beaten path. (And if you are not interested in these, there is little point in playing the game anyway.) As you explore, you come across developer notes. Most of these are flavor, but some play a crucial role in figuring out the background of what is going on. Aside from those, there are also audio logs – an obvious System Shock homage – with bits and pieces of conversations among the development team, or Ish Gilder’s solo, authorial commentary. Well-written, they help flesh out the characters and add a touch of comedy to what is otherwise presented as the grim and torturous process of developing a complete, shippable game, hindered by too many things – from tiny bugs and code limitations to the development team’s irreconcilable design goals or their despair over the inability to ever finish the damn thing.

The Magic Circle

“’What is The Magic Circle?’ It’s an old idea. I draw a line around any given space – call it roundish. And inside it, we agree on new rules of behavior. For the fun of it. The result, we call a ‘game’.”

– Ish Gilder

The characters themselves are an odd, but also familiar, bunch. Ish “Starfather” Gilder, the project lead, is a cross between Richard Garriott (Lord Brit-Ish) and Peter Molyneux; megalomaniacal, brilliant, lost in his own world. He is obsessed with outer space and hosts ridiculous LARPing parties (“orgies,” as another character suggests) at his castle. To drive the point home, the penultimate part of the game also seems to be a play on the famous episode of killing Lord British during Ultima Online’s 1997 beta test. Emphasizing the longevity of his career, the game has him reminisce about what I take to be a reference to the 1980s “anything goes” sort of creative freedom: “Back then I just wrote… whatever I wanted you to imagine, and was shocked when you paid me so well.”

Sometimes, Ish Gilder’s obsession with story can take him in a parodic “social tolerance” direction.

At the same time, Ish also cares deeply about the game and even takes a home-equity loan to fund its development. Having been in the industry since the 1980s, however, it is unclear if he still has what it takes to deliver the perfect game that his fans faithfully – but ever more impatiently – expect. This dormant yet potentially explosive clash between fan demands and developer illusions is one of the game’s leitmotifs, reaching its climax in the second act, but also finding its embodiment in another major antagonist, Coda Soliz, an intern, a streamer, and a devoted Ish Gilder fan – with a twist I will not spoil. Suffice it to say, Coda comes from within the fan community and retains her ties to it. She also subscribes to the “by gamers, for gamers” motto perhaps a little too literally.

Then there is Old Pro, the “anti-hero,” as he is called by Ish, communicating with you through weird talking stone heads you discover around the world. His “anti,” however, is not “BioWare evil” – it is a Promethean rebelliousness of an in-game character gone rogue, the impulse to rip control of what he perceives to be his world from the gods’ hands and take it for himself, to disrupt the pre-programmed world.

Ish, Coda, and even Old Pro are similar, in that each lives inside a very limited “circle” of reality, which they regard as the sole truth, incapable of seeing the vanity of clinging to their narrow standpoint. As Old Pro himself succintly puts it, “People don’t arc. They loop.”

“The gods’ve promised that they’ll tie off this story in a neat little bow. Everyone will confront a “demon,” learn a hard-won lesson, and complete an “arc.” But that’s a crock – watch ‘em long enough and you’ll see. People don’t arc. They loop.” – Old Pro

Not just people, though. This kind of loop, not arc, is characteristic of the game’s development going in circles, as well as the industry itself. Do we discard a System Shock in favor of a generic fantasy RPG that, however, we can probably ship? Old Pro is understandably irritated at that: “I had this world near to fixed, despite the gods. Then they scrap the whole damn thing and start over with the Magic Frickin’ Kingdom up there.” The important question is, however, what do we discard next? Player agency?

Ish Gilder’s sci-fi game was supposed to be a tale of the Space Station LIMINA (liminal: relating to a transitional or initial stage of a process) “and its fateful encounter with the circle.” The “magic circle” is apparently developer lingo for the self-enclosed illusion that a video game creates, into which you escape from the heat death of the universe – only to “come back dead, but wearing this beatific grin.” It is, however, also the aforementioned loop. Similarly to Coda, Maze Evelyn, the third key member of the team, used to be an intern and a gamer. She also pushed for adding multiplayer to the game – the sort of player-driven experience that was regarded as a panacea not so long ago. (Old Pro: “In my day, the gods were cocky. Figured they could handle more than one Hero.”) Now though, she simply wants out of the endless circle. In this, she is sort of on your side.

Maze cannot get out, though, due to contractual obligations. Neither can Ish, with his grand ideas and his home-equity loan, or Coda with her different, if no less feverish idea of what a perfect game involves. The finale of Coda’s storyline in parts one and two of the game (leaving the third act aside for now) loops back to Maze’s multiplayer obsession and exposes its destructive aspect. At the same time, Coda views Maze’s desire to escape as betrayal (“Maze Evelyn, you rose from the fan community, but you have forgotten us! And before we fire you: you will atone!”). True to the musical meaning of her name, Coda makes a final attempt to enact the closure of the circle. Turns out, it is not just harder than it sounds – the circle is porous, and the “real world” is not completely separate from what is inside. Whereas Ish and Maze can provoke sympathy, Coda hardly ever does, especially as she is shown rallying the mob at one point in the game. Fans, too, are shown to be aggressive – and then bored. We may sympathize with Ish, but they do not.

“I see every punchline coming, I smirk at the idea of a joke. This ain’t about pity – a god oughta take some joy in his work.” – Old Pro on the gods that failed

That is not all there is to the story, though. Coda may be a parody of nostalgic fans, but her one-sidedness serves to shed light on how old, impotent – and stuck in a loop that is dragging him down – Ish Gilder himself has become (“Wow – how old is this stuff? My god… it’s… years. I’ll be sixty-one in the fall, Coda. No family. For better or worse this – is what they’ll remember me by”). Game development is tiring. Looping is extremely tiring, too. As a consequence, the temptation is to do away with perfection or maybe even abandon the “gameplay” part because let’s be honest: it requires so much work.

From Notgames (Forward) to Games

“Probably not many gamers are aware of the term notgames, coined by Tale of Tales’ Michaël Samyn in 2010. The whole discussion around this artistic challenge – removing games from video games – was fascinating and inspiring. I feel like it made me a better game designer, as stripping games off their previously unquestioned features – and then putting them back together piece by piece – helped me understand them better.”

– Adrian Chmielarz, The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, “What Really Happened to Tale of Tales’ Sunset” @ Gamasutra

“This is my world. Told ya I was old.”

– Old Pro to the player

The Magic Circle references almost the entire history of game development. Allusions to different periods and gameplay styles abound, some direct, others more subtle. The 1980s play a role, the 1990s are featured prominently, but so is the present day – the epoch of player convenience on one hand (from quest markers to corridor design) and “notgames” on the other.

Notgames like Tale of Tales’ titles, Dear Esther, Journey, Kentucky Route Zero or Gone Home, also known derisively as “walking simulators,” attempt to subvert the expectations of what a video game is. To that end, they usually focus on the narrative, the atmosphere, and the player’s feelings in contrast to (the traditionally conceived notion of) player agency, exposing the latter’s limits as they have been internalized by the industry. Notgames are literally de-constructive, as they disassemble gameplay down to its basic components like walking around and triggering narrative or evocative events. For the most part, they present themselves as empathic experiences that purposefully avoid challenging the player, except emotionally. No matter how hard Adrian Chmielarz, the developer behind The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, criticizes Tale of Tales’ latest output, Sunset, his game is itself prefaced by “This is a narrative experience” – and indeed, has no gameplay “obstacles” to speak of. As such, it is perfectly in spirit of Michaël Samyn’s manifesto.

“You say you stand for ‘all players’ but look – at least one has their own ideas. And now, it’s their turn.” – Maze Evelyn, talking to Coda about the protagonist

Now, deconstruction can be important to lay bare what makes a game. However – and here you can see that The Magic Circle has followed these developments closely – what if we start from that zero point and have the player re-construct gameplay instead? Given that notgames eschew challenge, this zero point can also incorporate the flip side of the same industry, AAA player convenience (quest markers, linearity, conveniently placed collectibles). In fact, I believe the term “notgame” can easily be extended to include the AAA side, too, as well as something like Telltale’s “experiences”. However, now that the industry has gone from games to notgames, what if we go in the opposite direction? After all, even if some or even most players are content with being stripped of their free will, what if there is one player who is not?

In asking these questions, and following them through in its gameplay, The Magic Circle breaks with the notgame design – and calls for a return to Looking Glass sensibilities. At first glance, the two have a common goal: doing away with things getting in the way of the player’s immersion. However, they approach it in conflicting ways. Gone Home’s developers may have been influenced by LGS, but The Magic Circle is at its polemical best in showing that notgames and Looking Glass-style games proceed in opposite directions. “Environmental storytelling” is by itself not enough. Notgames choose to outright ignore gameplay instead of reassessing the ways player freedom can be brought about or enabling interactive tool-focused design. By emphasizing obstacle-based exploration and emergent gameplay, The Magic Circle sides with games against notgames, even as it starts from the latter as its point of reference.

The Magic Circle is, in other words, a de-construction of a notgame and a re-construction of a game. At the same time, it is also aware of game development’s limits. A game with infinite player freedom may be impossible due to technical, financial, and time constraints, while a non-game stripped of the more complex forms of active agency is unsatisfactory – not to the developer maybe, but certainly to you, the odd player. Not coincidentally, it is precisely from a notgame that Old Pro sets you free – and it is another notgame that you disrupt under the guise of the E4 demo.

“The gods can’t predict you. So they … invoke you to win an argument, like you’re an evil spirit.” – Old Pro to the player

“Nothing here seems real. That’s good! See, the gods of this place mean to kill that disbelief. I aim to keep it alive.” – Old Pro

In all that, The Magic Circle is very old-fashioned. As it happens, the way forward is by picking up a thread that was lost and buried, just like Space Station LIMINA underneath the Magical Mushroom Kingdom. Not in order to be stuck in the past like Old Pro, of course, but precisely to move forward.

That is not to say that The Magic Circle embraces player agency unreservedly, either. It has enough critical sense to see its limitations and perils. Old Pro and Coda both show, in different ways, that giving full control to the player is not always well-advised. Some of the commentary implies that Looking Glass’ goal of endless emergence and interactivity is utopian. Having the player fully (co-)author the game, of which Doug Church and Randy Smith dreamed, is impossible unless, ironically, the game’s A.I. itself were evolving – unless the player were, in a sense, the game’s A.I. As one of the characters puts it, “What would I even say?? The game woke up and tried to ship itself?” – the humorous mirror image of the developers trying to control every player action.

It is in that context that I find the third, final part of the game unsatisfactory. For reasons I will leave for you to discover, it has you construct a short dungeon crawler game of your own with extremely limited tools, which then gets reviewed by fictive game press. To cut a long story short, you build a generic dungeon crawl and get “8/10” reviews for it. The gameplay in this part is not just different – it gets disappointingly simplistic. Gone is the exploration. Gone are both player freedom and learning or experimenting with new tools. Thematically, too, whereas the first two parts, the Overworld and the E4 demo, are all about obstacles on the ambitious way to a perfect game, to player and developer freedom, the third part makes you simply give up all ambition altogether. If a linear hack’n’slash dungeon crawler is good enough to be shipped and positively reviewed, then why bother with something complex? This may not be thematic inconstency as such – after all, one could argue that this kind of ending is fitting in a way – but it is, I believe, thematic reductionism.

It is when it comes to characterization that I found act three to be at its most inconsistent with the rest of the game. Given their design sensibilities in parts one and two, you would think Old Pro and Coda should be disappointed by the kind of linear, non-interactive game you are building here. Instead, they give up all talk of player agency and cheer as you pick up a health potion or slay a monster in two simple swings, or get bored if there is no uninterrupted action to keep them entertained, all the while delivering some of the game’s most cringeworthy lines. In all that, depending on how you interpret this abrupt change, The Magic Circle either gets too “meta” for its own good or oversimplifies the main points of the first two acts – no matter if you take the third act to be a pessimistic take on where the industry is headed, a commentary on instant gratification and the ineptness of game journalism, or a triumphalist pandering to the industry and the press, which got lambasted in acts one and two. Even if the message of the third act is supposed to be that everything in the industry falls back into place on its circular course, it should not, I believe, have been so reductionist in its gameplay and writing.

Conclusion

“Don’t you understand this is not a comedy – this is my life’s work! You don’t care about any of this, do you? You’re just here to leer at a train wreck!”

– Ish Gilder, during the E4 presentation

“Things get real meta. So buckle up.”

– Old Pro to the player

The Magic Circle is a gameplay-focused commentary on the industry, with a clever premise, creative exploration and puzzle- (or rather, obstacle-)solving, and some genuinely fun, and funny, parts. However, I find that it ultimately fails as a “stand-alone” game, even if it does so in an interesting way. It is essentially an interactive critique. For those unfamiliar with the Looking Glass legacy or who do not understand what this style of design is about, too much of The Magic Circle’s message – and even the cleverness of its gameplay – is bound to fall flat.

Partly as a result of acts two and three being so divorced from the first, The Magic Circle never lives up to the full potential of its gameplay. The size and freedom of the Overworld, the number of powers and special properties, and the amount of content as a whole, fall just short of what would be required for it to stand on its own. The Magic Circle itself is aware of that, with some of the characters commenting on the limits of the game’s budget and scope, but again, while fine for a commentary, and while it purposefully distances itself from any pretense of completeness or perfection, it is a shame that the first, most free-form part of the game ends just as you have gotten comfortable with the tools and the second and third fail to offer a comparable degree of freedom or sophistication.

The commentary itself is mostly fine, and to the point. The industry is plagued by development hell, poor ideas, ambitious ideas that cannot be realized, corridor design and lack of player agency, developers who consider themselves to be gods but are in fact control freaks distrusting the player, as well as obsessed fans who mirror those developers in their own perverted way. Aimed at people addicted to the “game” part of video games, The Magic Circle ultimately cautions you against taking video games too seriously – which is what everyone from Ish to Coda to Old Pro does, with fatal consequences. Whenever the commentary may not be quite on point, it leaves enough room for ambiguity to make up for that. The ending sequence was, however, a let-down to me.

“He told the first story – and ruined the first game with it.” – Maze Evelyn on the origin of games

For all its problems, though, it is refreshing that The Magic Circle emphasizes gameplay to this degree. Even if, for various reasons, it effectively remains stuck between a game and a notgame, it does demonstrate one thing convincingly: notgames may be a fact, a fad or an inspiration, but at this point, we need to move beyond them. A de-construction is not an end in itself; its purpose is to be followed by a re-construction. Inside the world of The Magic Circle, developers are incapable of that. Whether the industry at large is, remains to be seen.

The Magic Circle is available on Steam. I am grateful to Infinitron, felipepepe, and sser for their feedback and suggestions on an earlier version of this article.