RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Ian Boswell and Martin Buis on The Dark Heart of Uukrul

RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Ian Boswell and Martin Buis on The Dark Heart of Uukrul

Codex Interview - posted by Crooked Bee on Thu 26 July 2012, 20:41:59

Tags: Broderbund Software; Ian Boswell; Martin Buis; Retrospective Interview; The Dark Heart of UukrulCorrupted by the evil wizard Uukrul, the underground city of Eriosthe is but a shadow of its former self, its passages now twisted beyond a mortal's understanding. The Dark Heart of Uukrul, a first person turn- and party-based dungeon-crawling CRPG with top-down Goldbox-like combat released by Broderbund in 1989 for Apple II and PC, entrusts you with a single task: cleanse Eriosthe of evil, no matter the cost. And the cost will be high, probably higher than you imagine; Uukrul knows you are coming, and he will be prepared.

In this installment of the RPG Codex retrospective interview series, we present you with an interview with Dark Heart of Uukrul's co-designers, Ian Boswell and Martin Buis, as well as a brief retrospective introducing the game. I will quote generously from the interview for you to have a taste of it:

We are grateful to Ian and Martin for their time! I would also like to thank Alex, Jaesun, VentilatorOfDoom and Zed for their comments on an earlier version of the retrospective.

Read the full article: RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Ian Boswell and Martin Buis on The Dark Heart of Uukrul

In this installment of the RPG Codex retrospective interview series, we present you with an interview with Dark Heart of Uukrul's co-designers, Ian Boswell and Martin Buis, as well as a brief retrospective introducing the game. I will quote generously from the interview for you to have a taste of it:

Dark Heart of Uukrul features some of the best dungeon design in the history of the genre, up there with such games as Wizardry IV or Chaos Strikes Back. How did you go about designing the dungeons, and what are the ones you remember the most fondly?

Ian Boswell: We didn’t want the maze to be constrained in a box, made up of levels, with each of them square. That seems very artificial. We wanted it to sprawl and spread out, including going up and down as well, like real caves and tunnels would. With a simple grid co-ordinate trick, we were able to implement this. It makes exploring the dungeon regions a lot more mysterious, even scary, because you have no idea where it’s going to lead or how far you are from your goal. For the player, mapping it becomes really challenging too.

Some of the regions are small, some are huge. Each has its own flavour, supported by the story narrative, and a design approach which makes each region feel different as you explore it. [...]

Martin Buis: The levels also tell a story and have a real location, so we wanted to convey a real sense of space through their spralling layout, or indicate that you’d reached a new area by a change in architecture. We were too constrained to do much with the visuals, so that was conveyed in the layout. [...]

Dark Heart of Uukrul is widely considered one of the most challenging CRPGs out there. Was it your intention right from the start to create an expert level scenario? What prompted that decision, and why the emphasis on puzzles?

Ian Boswell: [...] Both Martin and I were fond of puzzles and intellectual challenges, so we imbedded some of our favourites into the game, and created new ones of our own. The very best puzzles, I find, are ones where you see the pieces, but the “big picture” is hidden from view until you put the pieces together the right way, and then the logic dawns on you and everything makes sense.

Martin Buis: One of the design points we really wanted to get across was that dying was a really big deal in Uukrul, and that this would drive combat and exploring to be more emotionally charged and encourage times when the player would be aggressive and times when the player would be cautious. This meant that there had to be consequences to death, and even some fatal traps that you couldn’t escape. We were loathe to allow backups and reincarnation as these would weaken that feeling. Playing the game, and reading walk-throughs, I’m pleased that this aspect of the game comes through.

We both enjoyed puzzles a lot, and that was a big differentiator for how we thought about the game. A lot of the pleasure in games is about learning the rules of the game, and then discovering how to exploit them. So we tried to incorporate that at all levels of the gameplay. There are little puzzles, like how to explore an area, puzzles with longer arcs, like how priests work, and the overall game story. For the harder puzzles we worked to ensure that there were multiple solutions, so that you didn’t always need to solve them intellectually.

Dark Heart of Uukrul's character development is quite unorthodox, especially as far as magic users are concerned. Both the priest and the magician gain not only in levels, but also in the number and quality of rings equipped, each dedicated to specific deities or magic arcana. Obtaining new rings is a different form of character progression, woven in tightly to exploration and combat. What were the influences and the rationale behind this system?

Ian Boswell: I remember that whole system came to me while I was waiting at a bus stop, and there was a woman waiting there who was wearing these big, gaudy rings on every finger. In the game, the rings give a tangible measure of progression through magic powers, or spiritual powers, more structured than the usual D&D spell progression. Each finger represents a discipline or deity, and the metal of the ring on that finger represents the level of spells or prayers you can access.

Martin Buis: We also wanted to make a strong differentiation between rewarding the player for magic and prayers. We hit upon the idea of making the wizard very deterministic, and the priest very non-deterministic. I’d done psychology and was interested in exploring how Fixed Response and Variable Response schedules might be used in a game, and this worked. I think that it worked out pretty well. I particularly like the way the priest starts out frustrating and a liability to the party, but by the end is a mighty fighting machine.

Can you describe the reception the game got and your reaction to it? In retrospect, would you have changed anything about the game? Is there anything you would have done differently?

Ian Boswell: When Broderbund signed us up, there was a window where computer RPGs were hot property, but the window didn’t stay open long enough. It took us too long to complete the game, and I’d say we missed the market by 6-12 months. Broderbund published it, but by then RPGs were “last year’s model”. They did little to promote or advertise the game, and it sold only modestly, something around 5,000 copies.

The reception from the public however, from the few people that actually know about the game, has always been really positive. Even now 25 years later, I still get an occasional email from somebody telling me how much they enjoyed the game, especially the puzzles!

Martin Buis: We had aimed at beating the technical sophistication of Wizardry when we started, but it was a moving target and by the time we delivered we were a little behind the start of the art. I think that the lack of sound was probably a big factor in the game being overlooked in the market place. About the time Uukrul came out Id released Wolfenstein, and everyone’s expectations of what you could do with computers changed. Really, the whole genre of thoughtful games seems to have disappeared, and casual gaming seems to be pushing things further down the ‘stateless’ approach to gaming. [...]

Ian Boswell: We didn’t want the maze to be constrained in a box, made up of levels, with each of them square. That seems very artificial. We wanted it to sprawl and spread out, including going up and down as well, like real caves and tunnels would. With a simple grid co-ordinate trick, we were able to implement this. It makes exploring the dungeon regions a lot more mysterious, even scary, because you have no idea where it’s going to lead or how far you are from your goal. For the player, mapping it becomes really challenging too.

Some of the regions are small, some are huge. Each has its own flavour, supported by the story narrative, and a design approach which makes each region feel different as you explore it. [...]

Martin Buis: The levels also tell a story and have a real location, so we wanted to convey a real sense of space through their spralling layout, or indicate that you’d reached a new area by a change in architecture. We were too constrained to do much with the visuals, so that was conveyed in the layout. [...]

Dark Heart of Uukrul is widely considered one of the most challenging CRPGs out there. Was it your intention right from the start to create an expert level scenario? What prompted that decision, and why the emphasis on puzzles?

Ian Boswell: [...] Both Martin and I were fond of puzzles and intellectual challenges, so we imbedded some of our favourites into the game, and created new ones of our own. The very best puzzles, I find, are ones where you see the pieces, but the “big picture” is hidden from view until you put the pieces together the right way, and then the logic dawns on you and everything makes sense.

Martin Buis: One of the design points we really wanted to get across was that dying was a really big deal in Uukrul, and that this would drive combat and exploring to be more emotionally charged and encourage times when the player would be aggressive and times when the player would be cautious. This meant that there had to be consequences to death, and even some fatal traps that you couldn’t escape. We were loathe to allow backups and reincarnation as these would weaken that feeling. Playing the game, and reading walk-throughs, I’m pleased that this aspect of the game comes through.

We both enjoyed puzzles a lot, and that was a big differentiator for how we thought about the game. A lot of the pleasure in games is about learning the rules of the game, and then discovering how to exploit them. So we tried to incorporate that at all levels of the gameplay. There are little puzzles, like how to explore an area, puzzles with longer arcs, like how priests work, and the overall game story. For the harder puzzles we worked to ensure that there were multiple solutions, so that you didn’t always need to solve them intellectually.

Dark Heart of Uukrul's character development is quite unorthodox, especially as far as magic users are concerned. Both the priest and the magician gain not only in levels, but also in the number and quality of rings equipped, each dedicated to specific deities or magic arcana. Obtaining new rings is a different form of character progression, woven in tightly to exploration and combat. What were the influences and the rationale behind this system?

Ian Boswell: I remember that whole system came to me while I was waiting at a bus stop, and there was a woman waiting there who was wearing these big, gaudy rings on every finger. In the game, the rings give a tangible measure of progression through magic powers, or spiritual powers, more structured than the usual D&D spell progression. Each finger represents a discipline or deity, and the metal of the ring on that finger represents the level of spells or prayers you can access.

Martin Buis: We also wanted to make a strong differentiation between rewarding the player for magic and prayers. We hit upon the idea of making the wizard very deterministic, and the priest very non-deterministic. I’d done psychology and was interested in exploring how Fixed Response and Variable Response schedules might be used in a game, and this worked. I think that it worked out pretty well. I particularly like the way the priest starts out frustrating and a liability to the party, but by the end is a mighty fighting machine.

Can you describe the reception the game got and your reaction to it? In retrospect, would you have changed anything about the game? Is there anything you would have done differently?

Ian Boswell: When Broderbund signed us up, there was a window where computer RPGs were hot property, but the window didn’t stay open long enough. It took us too long to complete the game, and I’d say we missed the market by 6-12 months. Broderbund published it, but by then RPGs were “last year’s model”. They did little to promote or advertise the game, and it sold only modestly, something around 5,000 copies.

The reception from the public however, from the few people that actually know about the game, has always been really positive. Even now 25 years later, I still get an occasional email from somebody telling me how much they enjoyed the game, especially the puzzles!

Martin Buis: We had aimed at beating the technical sophistication of Wizardry when we started, but it was a moving target and by the time we delivered we were a little behind the start of the art. I think that the lack of sound was probably a big factor in the game being overlooked in the market place. About the time Uukrul came out Id released Wolfenstein, and everyone’s expectations of what you could do with computers changed. Really, the whole genre of thoughtful games seems to have disappeared, and casual gaming seems to be pushing things further down the ‘stateless’ approach to gaming. [...]

We are grateful to Ian and Martin for their time! I would also like to thank Alex, Jaesun, VentilatorOfDoom and Zed for their comments on an earlier version of the retrospective.

Read the full article: RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Ian Boswell and Martin Buis on The Dark Heart of Uukrul

RPG Codex Retrospective Interviews is a series that grew out of our fascination with the rich history of computer role-playing games. It focuses on developers and individual titles that made a unique or significant contribution to the genre, aiming to cover a developer's career and approach to RPG design or, respectively, the most relevant aspects of the game in question and the design philosophy behind it.

In today's installment of the series, we present you with an interview with Dark Heart of Uukrul's co-designers, Ian Boswell and Martin Buis, as well as a brief retrospective introducing the game.

RPG Codex Retrospective: The Dark Heart of Uukrul

[Written by Crooked Bee]

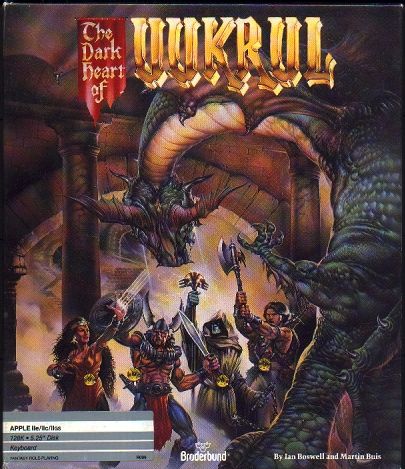

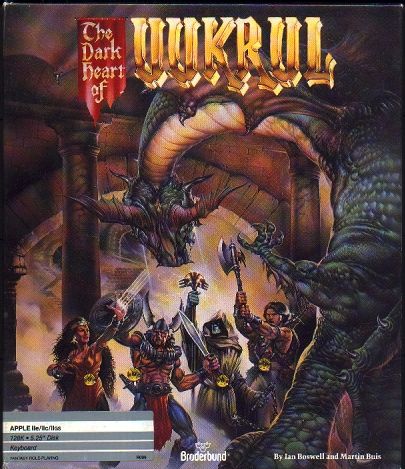

Dark Heart of Uukrul's Apple II box cover

Interview with Ian Boswell and Martin Buis

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and how your decision to develop a computer role-playing game came about? Did you come from pen and paper RPGs?

You co-designed Dark Heart of Uukrul. What were your roles on the game?

Broderbund was not exactly known for its role-playing games. How did you come in contact with them? Did they influence the final state of the game or the development process in any way?

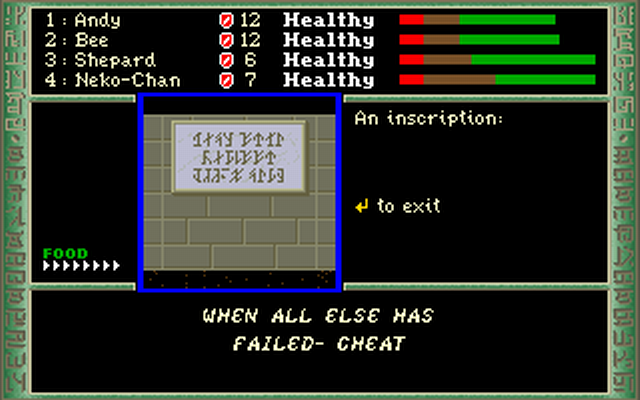

First person when in exploration mode, Dark Heart of Uukrul switches to top-down for combat encounters, played out on a battlefield representing a zoomed in view of the surrounding dungeon area.

What were your goals with Dark Heart of Uukrul? What did you set out to do with it, and what were some of the RPGs, computer or pen and paper, that influenced the game's concept and design?

Dark Heart of Uukrul is widely considered one of the most challenging CRPGs out there. Was it your intention right from the start to create an expert level scenario? What prompted that decision, and why the emphasis on puzzles?

One of the most famous and ingenious puzzles in Dark Heart of Uukrul is the crossword puzzle. Who came up with the idea and how tricky was it to implement it?

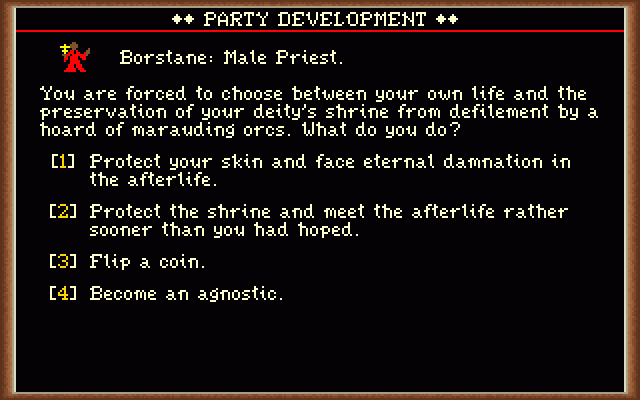

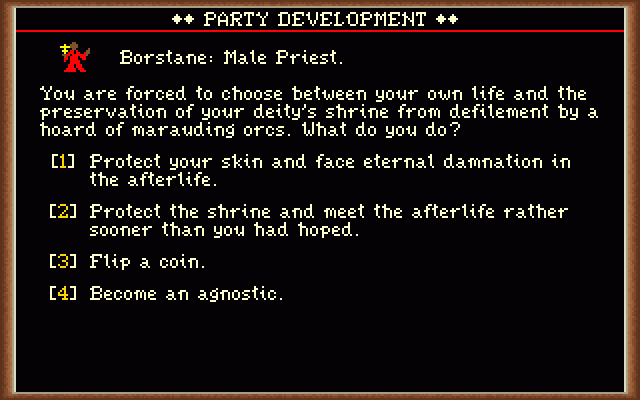

Your characters' starting attributes in Dark Heart of Uukrul are determined via a Q&A character creation system.

Dark Heart of Uukrul features some of the best dungeon design in the history of the genre, up there with such games as Wizardry IV or Chaos Strikes Back. How did you go about designing the dungeons, and what are the ones you remember the most fondly?

I'd also like to talk about the Cube, which was, I assume, influenced by Wizardry IV's Cosmic Cube. How did you approach designing it?

Another dungeon I'd like to discuss separately is Chaos, the final dungeon. Encounter-free, it relies exclusively on illusions and finding an underlying logic to them. As such, it is one of the most unique dungeons in any CRPG. Was there anything in particular that inspired it?

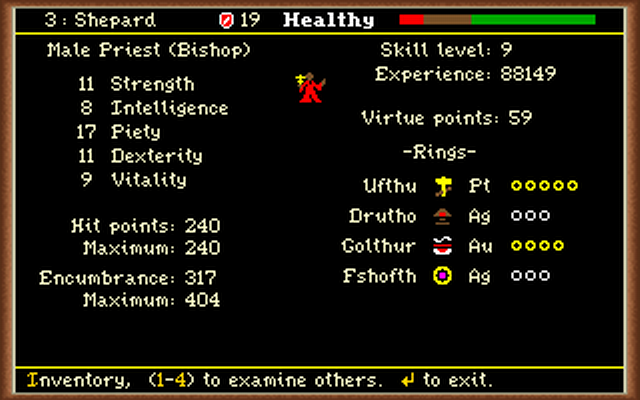

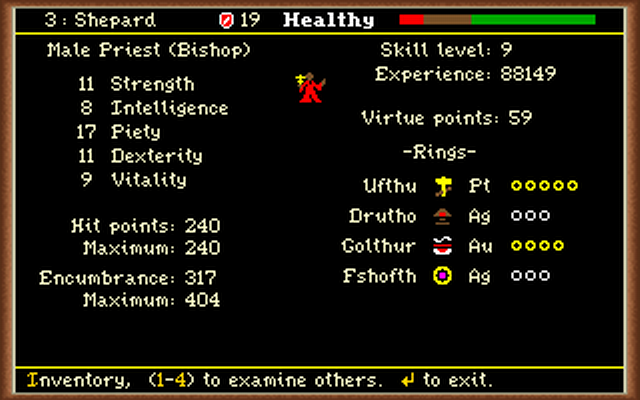

The Priest and the Magician not only gain levels, they also gain in the number and quality of rings equipped, with each one dedicated to specific deities or magic arcana, ranging from iron to crystal.

Dark Heart of Uukrul's character development is quite unorthodox, especially as far as magic users are concerned. Both the priest and the magician gain not only in levels, but also in the number and quality of rings equipped, each dedicated to specific deities or magic arcana. Obtaining new rings is a different form of character progression, woven in tightly to exploration and combat. What were the influences and the rationale behind this system?

Speaking of the magic system, how did you come up with it (and is there any meaning to the spell and prayer names)?

There is character creation in the game (the starting statistics for the party are determined by the player's answers to a number of questions, similar to the system used in Ultima IV), but the classes are fixed: every party consists of a Fighter, a Paladin, a Priest, and a Magician. What prompted this decision? Was it an emphasis on teamwork and cooperation between the classes?

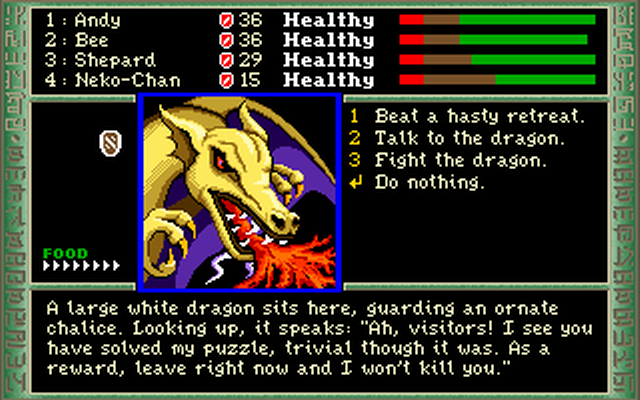

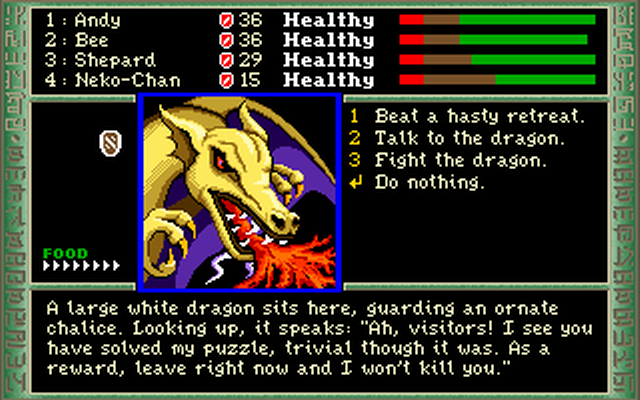

Sometimes the most reasonable option is to beat a hasty retreat.

Dark Heart of Uukrul features a very advanced save system, arguably the most optimal to this day. Through the game the party comes across sanctuaries, acting as places to save and rest. These act as checkpoints, but you can also save anywhere between sanctuaries, even though those saves are overridden upon entering combat and character deaths. What was the philosophy behind the save system?

The idea to present the plot via apparitions (or visions) of Mara is as memorable as it is rare. Personally, I can only recall one other 1980s CRPG that did something similar: Tower of Myraglen (1987) by Richard Seaborne. Were you aware of that game? Why did choose to go for this kind of presentation?

Dark Heart of Uukrul had some very basic graphics. Personally I did not mind that, but what did that have to do with?

Can you talk a bit about the development process? How long did it take you, and what were the main challenges involved?

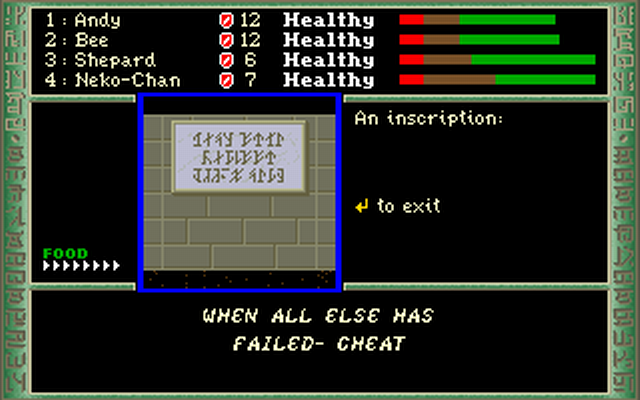

Dark Heart of Uukrul isn't particularly ashamed of its difficulty.

Can you describe the reception the game got and your reaction to it? In retrospect, would you have changed anything about the game? Is there anything you would have done differently?

After Dark Heart of Uukrul, you do not seem to have worked on any other video game. Why did you decide to leave the industry behind, and what have you been involved with since then?

Do you still play video games, and role-playing games in particular? Are there any that you have particularly enjoyed lately, or any that you tend to return to?

Great idea. You should call it "Dark Heart of Uukrul Forever".

We thank Ian Boswell and Martin Buis for their time! I would also like to thank Alex, Jaesun, VentilatorOfDoom and Zed for their comments on the retrospective.

In today's installment of the series, we present you with an interview with Dark Heart of Uukrul's co-designers, Ian Boswell and Martin Buis, as well as a brief retrospective introducing the game.

RPG Codex Retrospective: The Dark Heart of Uukrul

[Written by Crooked Bee]

Corrupted by the evil wizard Uukrul, the underground city of Eriosthe is but a shadow of its former self, its passages now twisted beyond a mortal's understanding. The Dark Heart of Uukrul, a first person turn- and party-based dungeon-crawling CRPG with top-down Goldbox-like combat developed by Ian Boswell and Martin Buis and released by Broderbund in 1989 for Apple II and PC, entrusts you with a single task: cleanse Eriosthe of evil, no matter the cost. And the cost will be high, probably higher than you imagine; Uukrul knows you are coming, and he will be prepared.

It is a triviality that bears repeating that the role-playing genre is far from monolithic: there are different kinds of CRPGs that focus on different things. To those who, like me, prefer CRPGs that are about abstraction rather than simulation, Dark Heart of Uukrul is pretty much a perfect game. It does not aim to model a superficially "realistic" NPC behavior, nor offers an "interactive" story or appeals to the player's emotions in an awkward attempt to get personal. It is aware that, much like a wargame, a CRPG is a mental exercise first and foremost, an abstraction of a task solved through character progression in the broad sense, one discarding everything superfluous and relying on a strict system of several abstract elements that both support and limit each other: character development, dungeon design, and combat, each of them a "puzzle" of its own, representing the various challenges your characters overcome in their progress, as well as a piece of the overarching logic that you must figure out to master the game. Dark Heart of Uukrul's achievement lies not only in the unorthodox ideas inherent in each of these components - it features some of the best dungeon, puzzle and character development design in the history of the genre - but also in balancing them in a way that accentuates their strengths and melts them into a highly challenging and memorable whole.

Enumerating the individual accomplishments and clever design decisions made by Dark Heart of Uukrul is a challenge in itself. If I had to compile a list of the genre's most unique and eventful dungeons, the ones that made a lasting impression on me, it would inevitably have to include not just one or two, but several or even most of Dark Heart of Uukrul's dungeons. The Cube, designed independently of Wizardry IV's Cosmic Cube and, in contrast to the latter, in "true" 3D so that the overall layout is seamless and makes sense; the infamous Crossword with its elegance and Hearthall with its sophisticated simplicity; the Pyramid with its remarkable card system; the exhausting Caverns with more to them than meets the eye; the oddness of the Battlefield maze with a spinner trap that haunts me still; the Great Engineer, a dungeon that makes full use of your imagination with its environmental hazards; the Palace, a "meta" role-playing area emphasizing the concept of chance via the roll of a die; and finally the Chaos, the most unorthodox and ingenious level ever created for a CRPG, encounter-free and illusion-based yet logical and perfectly climactic, alone worth a full playthrough of the game.

The game shares with Chaos Strikes Back the unrivaled feeling of a living and highly dangerous environment that makes the dungeon as such, and not just Uukrul, your antagonist, which is further underscored by the game's ending that I'm not spoiling for you here. There is a sense of exploration to the game that keeps you on your toes and makes you look forward to discovering what new and unexpected tricks the next dungeon section has to offer. The plot exposition also adds to that. Apart from the backstory given in the manual, the plot - in which you attempt to uncover the fate of the previous expedition that braved Eriosthe and disappeared - is presented to you via a series of visions, as well as notes and clues scattered throughout the dungeon. First person when in exploration mode, Dark Heart of Uukrul switches to top-down for combat encounters, played out on a battlefield representing a zoomed in view of the surrounding dungeon area. The game emphasizes teamwork in a way that other CRPGs rarely do, requiring each of your characters' input into combat, puzzle solving and plot-related activities, which however comes at the cost of making the party composition fixed, so that your group inevitably consists of a Fighter, a Paladin, a Magician and a Priest, their starting attributes and subclasses determined by a Q&A character creation system reminiscent of that made famous by Ultima IV. And while the first two classes are fairly traditional in their roles and abilities, the magic system is where Dark Heart of Uukrul shines again. Both the priest and the magician not only gain levels, they also gain in the number and quality of rings equipped, with each one dedicated to specific deities or magic arcana, ranging from iron to crystal. Obtaining new rings is, in many ways, a different form of levelling up, but one that is woven in much more tightly to the exploration process and whose specifics you must discover for yourself. The priest relies on prayers instead of spells, and not only do the prayers, being more of an appeal to a god than magic in the traditional fantasy sense, have a chance of failure, you must also decipher the purpose of each prayer, and this is no trivial task. And whereas the strength of many a CRPG's character development system draws more often than not on an established ruleset, be it D&D or whatever else, Dark Heart of Uukrul is an infrequent case where an attempt to come up with a "homebrew" system makes for a strong and engaging experience.

Alongside such games as Wizardry IV, Dark Heart of Uukrul is what used to be called an expert level scenario, not only in its combat, puzzle and dungeon design, but also in the save system the designers developed for it, arguably the most optimal to date. All through the game the party will come across sanctuaries, acting as places to rest, save and recuperate. These act as checkpoints, as although you can save between sanctuaries, those saves are overridden upon entering combat and character deaths. That means you can choose to play with permadeath according to the designers' original vision, making death meaningful but not in a way that is forced on you, and you can also save on exit so that your progress doesn't get lost whenever you have to quit the game to attend to more urgent matters.

Released just a bit too late to become popular, with graphical and sound limitations and lack of a proper advertising campaign, Dark Heart of Uukrul is now enjoying a niche cult classic status in an industry where, as Martin Buis observes in the interview that follows, "the whole genre of thoughtful games seems to have disappeared." One could argue this isn't quite so bad a fate.

It is a triviality that bears repeating that the role-playing genre is far from monolithic: there are different kinds of CRPGs that focus on different things. To those who, like me, prefer CRPGs that are about abstraction rather than simulation, Dark Heart of Uukrul is pretty much a perfect game. It does not aim to model a superficially "realistic" NPC behavior, nor offers an "interactive" story or appeals to the player's emotions in an awkward attempt to get personal. It is aware that, much like a wargame, a CRPG is a mental exercise first and foremost, an abstraction of a task solved through character progression in the broad sense, one discarding everything superfluous and relying on a strict system of several abstract elements that both support and limit each other: character development, dungeon design, and combat, each of them a "puzzle" of its own, representing the various challenges your characters overcome in their progress, as well as a piece of the overarching logic that you must figure out to master the game. Dark Heart of Uukrul's achievement lies not only in the unorthodox ideas inherent in each of these components - it features some of the best dungeon, puzzle and character development design in the history of the genre - but also in balancing them in a way that accentuates their strengths and melts them into a highly challenging and memorable whole.

Enumerating the individual accomplishments and clever design decisions made by Dark Heart of Uukrul is a challenge in itself. If I had to compile a list of the genre's most unique and eventful dungeons, the ones that made a lasting impression on me, it would inevitably have to include not just one or two, but several or even most of Dark Heart of Uukrul's dungeons. The Cube, designed independently of Wizardry IV's Cosmic Cube and, in contrast to the latter, in "true" 3D so that the overall layout is seamless and makes sense; the infamous Crossword with its elegance and Hearthall with its sophisticated simplicity; the Pyramid with its remarkable card system; the exhausting Caverns with more to them than meets the eye; the oddness of the Battlefield maze with a spinner trap that haunts me still; the Great Engineer, a dungeon that makes full use of your imagination with its environmental hazards; the Palace, a "meta" role-playing area emphasizing the concept of chance via the roll of a die; and finally the Chaos, the most unorthodox and ingenious level ever created for a CRPG, encounter-free and illusion-based yet logical and perfectly climactic, alone worth a full playthrough of the game.

The game shares with Chaos Strikes Back the unrivaled feeling of a living and highly dangerous environment that makes the dungeon as such, and not just Uukrul, your antagonist, which is further underscored by the game's ending that I'm not spoiling for you here. There is a sense of exploration to the game that keeps you on your toes and makes you look forward to discovering what new and unexpected tricks the next dungeon section has to offer. The plot exposition also adds to that. Apart from the backstory given in the manual, the plot - in which you attempt to uncover the fate of the previous expedition that braved Eriosthe and disappeared - is presented to you via a series of visions, as well as notes and clues scattered throughout the dungeon. First person when in exploration mode, Dark Heart of Uukrul switches to top-down for combat encounters, played out on a battlefield representing a zoomed in view of the surrounding dungeon area. The game emphasizes teamwork in a way that other CRPGs rarely do, requiring each of your characters' input into combat, puzzle solving and plot-related activities, which however comes at the cost of making the party composition fixed, so that your group inevitably consists of a Fighter, a Paladin, a Magician and a Priest, their starting attributes and subclasses determined by a Q&A character creation system reminiscent of that made famous by Ultima IV. And while the first two classes are fairly traditional in their roles and abilities, the magic system is where Dark Heart of Uukrul shines again. Both the priest and the magician not only gain levels, they also gain in the number and quality of rings equipped, with each one dedicated to specific deities or magic arcana, ranging from iron to crystal. Obtaining new rings is, in many ways, a different form of levelling up, but one that is woven in much more tightly to the exploration process and whose specifics you must discover for yourself. The priest relies on prayers instead of spells, and not only do the prayers, being more of an appeal to a god than magic in the traditional fantasy sense, have a chance of failure, you must also decipher the purpose of each prayer, and this is no trivial task. And whereas the strength of many a CRPG's character development system draws more often than not on an established ruleset, be it D&D or whatever else, Dark Heart of Uukrul is an infrequent case where an attempt to come up with a "homebrew" system makes for a strong and engaging experience.

Alongside such games as Wizardry IV, Dark Heart of Uukrul is what used to be called an expert level scenario, not only in its combat, puzzle and dungeon design, but also in the save system the designers developed for it, arguably the most optimal to date. All through the game the party will come across sanctuaries, acting as places to rest, save and recuperate. These act as checkpoints, as although you can save between sanctuaries, those saves are overridden upon entering combat and character deaths. That means you can choose to play with permadeath according to the designers' original vision, making death meaningful but not in a way that is forced on you, and you can also save on exit so that your progress doesn't get lost whenever you have to quit the game to attend to more urgent matters.

Released just a bit too late to become popular, with graphical and sound limitations and lack of a proper advertising campaign, Dark Heart of Uukrul is now enjoying a niche cult classic status in an industry where, as Martin Buis observes in the interview that follows, "the whole genre of thoughtful games seems to have disappeared." One could argue this isn't quite so bad a fate.

Dark Heart of Uukrul's Apple II box cover

Interview with Ian Boswell and Martin Buis

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and how your decision to develop a computer role-playing game came about? Did you come from pen and paper RPGs?

Ian Boswell: Martin and I were both studying Computer Science at Auckland University in the early 80s. We had played Wizardry I and II on Apple II, I think this would be 1982, and we were definitely inspired by that game, but at the same time we didn’t see anything that was technically beyond us. We had many ideas for ways that it could be done much better. It started as a spare time project, something we could tinker with, and we would see where it went. I think if we’d known how much time it would end up taking, we’d probably never have started!

We were both really keen on text-based adventures at the time, especially the intellectual aspect, the puzzle solving. There was very little of that in Wizardry, and we knew from the start that our (as yet unnamed) game would have the flavour of a puzzle-based, storytelling type adventure, not just a straight RPG.

I had played almost no pen-and-paper RPGs, though Martin had some experience with them. That wasn’t a bad thing. We agreed that we’d only follow the expected “rules” when it made sense, not be bound by what the D&D rulebooks said.

Martin Buis: I’d done wargaming and some D&D through school, and was a big fan of SciFi and Fantasy fiction, so the general area was one that I enjoyed. I’d made dice-based games too, and enjoyed the creation of the ruleset as much as the story and the interaction with other players. Ian and I met because we were doing both Comp Sci and music, and I remember playing Wizardry and working on projects day and night.

We started talking about building one together – unaware that that scale of the project would grow to what it finally became. It’s the old story of ‘if I’d known it was going to be that much work, I’d never have started it’; but the end result was very satisfying and a very different spin on the other games.

We were both really keen on text-based adventures at the time, especially the intellectual aspect, the puzzle solving. There was very little of that in Wizardry, and we knew from the start that our (as yet unnamed) game would have the flavour of a puzzle-based, storytelling type adventure, not just a straight RPG.

I had played almost no pen-and-paper RPGs, though Martin had some experience with them. That wasn’t a bad thing. We agreed that we’d only follow the expected “rules” when it made sense, not be bound by what the D&D rulebooks said.

Martin Buis: I’d done wargaming and some D&D through school, and was a big fan of SciFi and Fantasy fiction, so the general area was one that I enjoyed. I’d made dice-based games too, and enjoyed the creation of the ruleset as much as the story and the interaction with other players. Ian and I met because we were doing both Comp Sci and music, and I remember playing Wizardry and working on projects day and night.

We started talking about building one together – unaware that that scale of the project would grow to what it finally became. It’s the old story of ‘if I’d known it was going to be that much work, I’d never have started it’; but the end result was very satisfying and a very different spin on the other games.

You co-designed Dark Heart of Uukrul. What were your roles on the game?

Ian Boswell: We both had a hand in most things. I did more of the programming, and Martin did more of the plotting and design. But the most creative stuff usually emerged from collaborative sessions and many cups of coffee.

The maze design – which is huge – was broken into regions, one region being the area you explore between two consecutive sanctuaries. Mostly, one of us took responsibility for the detailed design of a given region, then when it was ready brought it back to the other for playthroughs and fine tuning. This is why many of the regions have a distinct theme or tone to them. Each of them “feels” different.

We also had to develop a lot of the required code libraries and design utilities that we needed. There was almost nothing available off the shelf, or open source, back then.

Martin Buis: We started out with more or less equal roles, but specialized as the project progressed. Ian was a fantastic developer and ended up doing all the code – I doubt that any of my code survived into the released game. I remember that Ian designed and wrote the maze drawing algorithm, which involved perspective views and hidden surface removal both of which were state of the art, in 6502 assembler in a single shot and that at the end of coding there were only two bugs that needed to be fixed. I don’t think I’ve ever seen an equivalent feat of programming.

The level, artwork, story and mechanics were very collaborative. A lot of what we had to do was working out how to get the most from the limitations that the memory, disk and processor imposed upon us. Within those limitations we tried to come up with innovative ideas that would advance the play without taxing our resources.

The maze design – which is huge – was broken into regions, one region being the area you explore between two consecutive sanctuaries. Mostly, one of us took responsibility for the detailed design of a given region, then when it was ready brought it back to the other for playthroughs and fine tuning. This is why many of the regions have a distinct theme or tone to them. Each of them “feels” different.

We also had to develop a lot of the required code libraries and design utilities that we needed. There was almost nothing available off the shelf, or open source, back then.

Martin Buis: We started out with more or less equal roles, but specialized as the project progressed. Ian was a fantastic developer and ended up doing all the code – I doubt that any of my code survived into the released game. I remember that Ian designed and wrote the maze drawing algorithm, which involved perspective views and hidden surface removal both of which were state of the art, in 6502 assembler in a single shot and that at the end of coding there were only two bugs that needed to be fixed. I don’t think I’ve ever seen an equivalent feat of programming.

The level, artwork, story and mechanics were very collaborative. A lot of what we had to do was working out how to get the most from the limitations that the memory, disk and processor imposed upon us. Within those limitations we tried to come up with innovative ideas that would advance the play without taxing our resources.

Broderbund was not exactly known for its role-playing games. How did you come in contact with them? Did they influence the final state of the game or the development process in any way?

Ian Boswell: When we had enough of the game working that it could be demonstrated, we asked a business acquaintance to show it around to a few publishers while on a trip to the States. The publishers were all based in California. We were in New Zealand, and communication with distant countries was a lot harder back then – no internet!

It turned out that Broderbund was actively looking for a fantasy RPG title, to respond to competitors like Wizardry and Ultima which were creating quite a buzz at that time. They liked Uukrul, and signed us up almost on the spot. I guess it was partly lucky timing.

Regarding influence… well their major influence on us was to get us to finish the thing! There was an awful lot of work still to be done, with just two people working in their spare time. They drove us to get it completed, but they were never too overbearing. And to their credit they never interfered with our creative control. They wanted to release the title while the RPG market was still hot. Sadly, by the time it was ready, we’d missed that window.

Martin Buis: We showed it to Broderbund, Electronic Arts and Activision. Broderbund were the most interested and helped with the art work as well. They were a great partner, but I think that working with a New Zealand based software house (well couple of students), was something that was new to them. In retrospect, we missed the sweet spot for the Apple market, and while we then made a port for the PC, Uukrul never established a strong brand or got great marketing.

One downside of the games market at that time was that copy protection was imposed upon us late in the process. We were a little hesitant to include it and wanted to work it into the game play a little. In particular, we were concerned about how the copy protection would interact with our game values around dying and backing up.

It turned out that Broderbund was actively looking for a fantasy RPG title, to respond to competitors like Wizardry and Ultima which were creating quite a buzz at that time. They liked Uukrul, and signed us up almost on the spot. I guess it was partly lucky timing.

Regarding influence… well their major influence on us was to get us to finish the thing! There was an awful lot of work still to be done, with just two people working in their spare time. They drove us to get it completed, but they were never too overbearing. And to their credit they never interfered with our creative control. They wanted to release the title while the RPG market was still hot. Sadly, by the time it was ready, we’d missed that window.

Martin Buis: We showed it to Broderbund, Electronic Arts and Activision. Broderbund were the most interested and helped with the art work as well. They were a great partner, but I think that working with a New Zealand based software house (well couple of students), was something that was new to them. In retrospect, we missed the sweet spot for the Apple market, and while we then made a port for the PC, Uukrul never established a strong brand or got great marketing.

One downside of the games market at that time was that copy protection was imposed upon us late in the process. We were a little hesitant to include it and wanted to work it into the game play a little. In particular, we were concerned about how the copy protection would interact with our game values around dying and backing up.

First person when in exploration mode, Dark Heart of Uukrul switches to top-down for combat encounters, played out on a battlefield representing a zoomed in view of the surrounding dungeon area.

What were your goals with Dark Heart of Uukrul? What did you set out to do with it, and what were some of the RPGs, computer or pen and paper, that influenced the game's concept and design?

Ian Boswell: I guess my first goal was just to see if I could handle a creative project that big. It was also a nice alternative to getting a real job.

We didn’t have a lot of direct influences from other games, apart from Wizardry which planted the seed in the first place. That’s probably why Uukrul ended up quite refreshingly different from other titles of the era.

We didn’t have a lot of direct influences from other games, apart from Wizardry which planted the seed in the first place. That’s probably why Uukrul ended up quite refreshingly different from other titles of the era.

Dark Heart of Uukrul is widely considered one of the most challenging CRPGs out there. Was it your intention right from the start to create an expert level scenario? What prompted that decision, and why the emphasis on puzzles?

Ian Boswell: I didn’t realize it was considered one of the most challenging. But that’s nice to know because we did set out to make the game memorable, and the things the player remembers most are solving challenges, not hacking up monsters. It’s the puzzles and the plot that people remember. Both Martin and I were fond of puzzles and intellectual challenges, so we imbedded some of our favourites into the game, and created new ones of our own. The very best puzzles, I find, are ones where you see the pieces, but the “big picture” is hidden from view until you put the pieces together the right way, and then the logic dawns on you and everything makes sense.

Martin Buis: One of the design points we really wanted to get across was that dying was a really big deal in Uukrul, and that this would drive combat and exploring to be more emotionally charged and encourage times when the player would be aggressive and times when the player would be cautious. This meant that there had to be consequences to death, and even some fatal traps that you couldn’t escape. We were loathe to allow backups and reincarnation as these would weaken that feeling. Playing the game, and reading walk-throughs, I’m pleased that this aspect of the game comes through.

We both enjoyed puzzles a lot, and that was a big differentiator for how we thought about the game. A lot of the pleasure in games is about learning the rules of the game, and then discovering how to exploit them. So we tried to incorporate that at all levels of the gameplay. There are little puzzles, like how to explore an area, puzzles with longer arcs, like how priests work, and the overall game story. For the harder puzzles we worked to ensure that there were multiple solutions, so that you didn’t always need to solve them intellectually.

Martin Buis: One of the design points we really wanted to get across was that dying was a really big deal in Uukrul, and that this would drive combat and exploring to be more emotionally charged and encourage times when the player would be aggressive and times when the player would be cautious. This meant that there had to be consequences to death, and even some fatal traps that you couldn’t escape. We were loathe to allow backups and reincarnation as these would weaken that feeling. Playing the game, and reading walk-throughs, I’m pleased that this aspect of the game comes through.

We both enjoyed puzzles a lot, and that was a big differentiator for how we thought about the game. A lot of the pleasure in games is about learning the rules of the game, and then discovering how to exploit them. So we tried to incorporate that at all levels of the gameplay. There are little puzzles, like how to explore an area, puzzles with longer arcs, like how priests work, and the overall game story. For the harder puzzles we worked to ensure that there were multiple solutions, so that you didn’t always need to solve them intellectually.

One of the most famous and ingenious puzzles in Dark Heart of Uukrul is the crossword puzzle. Who came up with the idea and how tricky was it to implement it?

Ian Boswell: That was me. I’ve always liked cryptic crosswords, the sort where each clue is a little puzzle in its own right, words which look like nonsense until you read them the right way. Coincidentally, a crossword grid can look like passages crossing each other in a dungeon map. So I decided to design a region where the passages formed a crossword, and build a multi-layered puzzle around that.

If we had just said “now here’s a crossword puzzle you have to solve”, it wouldn’t be special. Instead, without knowing what’s going on, you find your party walking around these passages that don’t appear to go anywhere, each passage contains a nonsense message, maybe you draw a map and notice that it’s symmetric, it looks a bit like… and the penny drops and you realize you’re walking around inside a crossword puzzle. I think it’s that very moment that players remember, more than anything else in the game. Then you’ve still got to solve the crossword clues, figure out what to do with the answers (they open secret doors), and work out how to use the strange information revealed behind those secret doors.

If we had just said “now here’s a crossword puzzle you have to solve”, it wouldn’t be special. Instead, without knowing what’s going on, you find your party walking around these passages that don’t appear to go anywhere, each passage contains a nonsense message, maybe you draw a map and notice that it’s symmetric, it looks a bit like… and the penny drops and you realize you’re walking around inside a crossword puzzle. I think it’s that very moment that players remember, more than anything else in the game. Then you’ve still got to solve the crossword clues, figure out what to do with the answers (they open secret doors), and work out how to use the strange information revealed behind those secret doors.

Your characters' starting attributes in Dark Heart of Uukrul are determined via a Q&A character creation system.

Dark Heart of Uukrul features some of the best dungeon design in the history of the genre, up there with such games as Wizardry IV or Chaos Strikes Back. How did you go about designing the dungeons, and what are the ones you remember the most fondly?

Ian Boswell: We didn’t want the maze to be constrained in a box, made up of levels, with each of them square. That seems very artificial. We wanted it to sprawl and spread out, including going up and down as well, like real caves and tunnels would. With a simple grid co-ordinate trick, we were able to implement this. It makes exploring the dungeon regions a lot more mysterious, even scary, because you have no idea where it’s going to lead or how far you are from your goal. For the player, mapping it becomes really challenging too.

Some of the regions are small, some are huge. Each has its own flavour, supported by the story narrative, and a design approach which makes each region feel different as you explore it.

The ones I remember most fondly are the Crossword Puzzle and the Chaos, and I see these are two that you’ve asked specific questions about. Both of them are so unlike what you expect to find in an RPG, yet both have an intricate design logic to them which becomes the very puzzle you have to solve.

Martin Buis: The levels also tell a story and have a real location, so we wanted to convey a real sense of space through their spralling layout, or indicate that you’d reached a new area by a change in architecture. We were too constrained to do much with the visuals, so that was conveyed in the layout.

I think that Ian did a great job with the Crossword level (and, as I recall it, The Cube) and they still feel like unique fresh ideas to me. I liked the generator level also, and the Chaos area.

Some of the regions are small, some are huge. Each has its own flavour, supported by the story narrative, and a design approach which makes each region feel different as you explore it.

The ones I remember most fondly are the Crossword Puzzle and the Chaos, and I see these are two that you’ve asked specific questions about. Both of them are so unlike what you expect to find in an RPG, yet both have an intricate design logic to them which becomes the very puzzle you have to solve.

Martin Buis: The levels also tell a story and have a real location, so we wanted to convey a real sense of space through their spralling layout, or indicate that you’d reached a new area by a change in architecture. We were too constrained to do much with the visuals, so that was conveyed in the layout.

I think that Ian did a great job with the Crossword level (and, as I recall it, The Cube) and they still feel like unique fresh ideas to me. I liked the generator level also, and the Chaos area.

I'd also like to talk about the Cube, which was, I assume, influenced by Wizardry IV's Cosmic Cube. How did you approach designing it?

Ian Boswell: Uukrul predates Wizardry IV, so there was no influence from it. I think the cube was Martin’s design. Another nice twist, because most of our dungeon spreads and sprawls over a wide area. But this region is just the opposite, packed tightly into a perfect 7x7x7 cube. Mapping and navigating it is challenging because there aren’t many standard passages, but there are a lot of vertical transitions. That opens up spatial puzzling. Designing it was the opposite of playing it – map it all out carefully first, then work out where the passages have to be.

Martin Buis: I recall that Ian made this level, so it’s interesting that he thought it was me! In any case, none of the level design was directly influenced by other games. We simply hadn’t played that many games, and enjoyed going our own way too much to repeat other people’s invention.

Martin Buis: I recall that Ian made this level, so it’s interesting that he thought it was me! In any case, none of the level design was directly influenced by other games. We simply hadn’t played that many games, and enjoyed going our own way too much to repeat other people’s invention.

Another dungeon I'd like to discuss separately is Chaos, the final dungeon. Encounter-free, it relies exclusively on illusions and finding an underlying logic to them. As such, it is one of the most unique dungeons in any CRPG. Was there anything in particular that inspired it?

Ian Boswell: Yes, we loved working on this one. Another twist, it’s the exact opposite of what you expect at the climax of an RPG. You’ve almost got to the end, your party has built up all these immense powers, vast wealth and treasures, the greatest weapons and the most potent magic… and it’s all useless. Nothing can get you through here except your wits.

I can’t recall what the specific inspiration would have been, but we both liked doing things that were unpredictable. Our dungeon mapping engine allowed us to implement some weird tricks, doing things with (x,y,z) co-ordinates that wouldn’t map correctly to real space. We’d largely avoided anomalies like that in the rest of the dungeon (although I think there was one “infinite” corridor somewhere!). But, hey, climax of the whole game, let’s have some fun. Walking around the Chaos really feels strange. You even feel scared to take a step forward because you may not be able to get back. But, it is a puzzle, not just random squares. It does have logic, and working that logic out bit by bit, through observing what happens where, reveals a satisfying solution.

You mentioned that the Chaos has no monster encounters at all. They would have been irrelevant at this point in the game, but in fact we had to eliminate them for a technical reason as well. The deliberately fractured nature of the dungeon mapping here would have broken our combat engine!

Martin Buis: I remember how we came up with this. We had been designing games with a game editor that allowed you to place walls, traps and so forth onto a level. The level was organized into a grid, but you could effectively cut up the grid and recombine it to make arbitrary shapes. You had to be careful that you constructed things correctly so that doors didn’t have just one side and so on. So there was a lot of thought and testing that needed to be done to make sure everything worked. I recalled thinking that it would be cool if we played with those rules to make a level where things were not consistent. Once we had that basic idea we worked it into the basic story line and added the puzzles. It was actually quite difficult to get a good puzzle working in such an arbitrary space, as you can’t as easily control how the player might move through such an open area.

I can’t recall what the specific inspiration would have been, but we both liked doing things that were unpredictable. Our dungeon mapping engine allowed us to implement some weird tricks, doing things with (x,y,z) co-ordinates that wouldn’t map correctly to real space. We’d largely avoided anomalies like that in the rest of the dungeon (although I think there was one “infinite” corridor somewhere!). But, hey, climax of the whole game, let’s have some fun. Walking around the Chaos really feels strange. You even feel scared to take a step forward because you may not be able to get back. But, it is a puzzle, not just random squares. It does have logic, and working that logic out bit by bit, through observing what happens where, reveals a satisfying solution.

You mentioned that the Chaos has no monster encounters at all. They would have been irrelevant at this point in the game, but in fact we had to eliminate them for a technical reason as well. The deliberately fractured nature of the dungeon mapping here would have broken our combat engine!

Martin Buis: I remember how we came up with this. We had been designing games with a game editor that allowed you to place walls, traps and so forth onto a level. The level was organized into a grid, but you could effectively cut up the grid and recombine it to make arbitrary shapes. You had to be careful that you constructed things correctly so that doors didn’t have just one side and so on. So there was a lot of thought and testing that needed to be done to make sure everything worked. I recalled thinking that it would be cool if we played with those rules to make a level where things were not consistent. Once we had that basic idea we worked it into the basic story line and added the puzzles. It was actually quite difficult to get a good puzzle working in such an arbitrary space, as you can’t as easily control how the player might move through such an open area.

The Priest and the Magician not only gain levels, they also gain in the number and quality of rings equipped, with each one dedicated to specific deities or magic arcana, ranging from iron to crystal.

Dark Heart of Uukrul's character development is quite unorthodox, especially as far as magic users are concerned. Both the priest and the magician gain not only in levels, but also in the number and quality of rings equipped, each dedicated to specific deities or magic arcana. Obtaining new rings is a different form of character progression, woven in tightly to exploration and combat. What were the influences and the rationale behind this system?

Ian Boswell: I remember that whole system came to me while I was waiting at a bus stop, and there was a woman waiting there who was wearing these big, gaudy rings on every finger. In the game, the rings give a tangible measure of progression through magic powers, or spiritual powers, more structured than the usual D&D spell progression. Each finger represents a discipline or deity, and the metal of the ring on that finger represents the level of spells or prayers you can access.

Martin Buis: We also wanted to make a strong differentiation between rewarding the player for magic and prayers. We hit upon the idea of making the wizard very deterministic, and the priest very non-deterministic. I’d done psychology and was interested in exploring how Fixed Response and Variable Response schedules might be used in a game, and this worked. I think that it worked out pretty well. I particularly like the way the priest starts out frustrating and a liability to the party, but by the end is a mighty fighting machine.

Martin Buis: We also wanted to make a strong differentiation between rewarding the player for magic and prayers. We hit upon the idea of making the wizard very deterministic, and the priest very non-deterministic. I’d done psychology and was interested in exploring how Fixed Response and Variable Response schedules might be used in a game, and this worked. I think that it worked out pretty well. I particularly like the way the priest starts out frustrating and a liability to the party, but by the end is a mighty fighting machine.

Speaking of the magic system, how did you come up with it (and is there any meaning to the spell and prayer names)?

Ian Boswell: I liked the distinction between spells and prayers. The Magician’s spells are reliable, if you have the ability to cast it (ring and points), a spell will work. But the Priest’s prayers are not reliable, they are merely pleas to the deity to act on your behalf. The prayers are potentially more powerful, and certainly more mysterious, than the magic spells. With a few of them, even working out what they do is a puzzle in itself.

For the most part, the spell and prayer names are just invented words or families of words. But there is the odd hidden joke, like “muzaq” which is a spell that brings forth a terrible noise.

Martin Buis: For the powers, we looked at all the variables and algorithms involved in the game and figured out how we could turn them into interesting spells. We even tried to do some forward looking time travel in the scrying mirror, since we knew the puzzles and the story was quite linear, we could infer what the player would be up to soon.

Another part of our thinking revolved around making the combat interesting. We liked the idea of emphasizing positioning and tactics in combat. There are combats where you charge in with the fighters and keep the priest and magician back, and others where you form a defensive line around weaker characters. Magic was a key part in making that a fluid thing, with distance spells, healing and summoning all having the ability to turn around a combat.

For the most part, the spell and prayer names are just invented words or families of words. But there is the odd hidden joke, like “muzaq” which is a spell that brings forth a terrible noise.

Martin Buis: For the powers, we looked at all the variables and algorithms involved in the game and figured out how we could turn them into interesting spells. We even tried to do some forward looking time travel in the scrying mirror, since we knew the puzzles and the story was quite linear, we could infer what the player would be up to soon.

Another part of our thinking revolved around making the combat interesting. We liked the idea of emphasizing positioning and tactics in combat. There are combats where you charge in with the fighters and keep the priest and magician back, and others where you form a defensive line around weaker characters. Magic was a key part in making that a fluid thing, with distance spells, healing and summoning all having the ability to turn around a combat.

There is character creation in the game (the starting statistics for the party are determined by the player's answers to a number of questions, similar to the system used in Ultima IV), but the classes are fixed: every party consists of a Fighter, a Paladin, a Priest, and a Magician. What prompted this decision? Was it an emphasis on teamwork and cooperation between the classes?

Ian Boswell: The overall plot progression requires the party to have one of each character class. We placed plot points through the game where (say) the vision of Mara would speak to the Magician, revealing vital information. That’s problematic if your party has no Magician. Also, I think it wouldn’t be possible to complete the game with one of the character classes missing. There are spells and prayers for example that are essential, and you’d not survive combats without a Fighter.

Martin Buis: This just was something we took as a fixed approach. Our combat system required it, and so much of the level design was devoted to each of the classes that variations would have been hard.

Martin Buis: This just was something we took as a fixed approach. Our combat system required it, and so much of the level design was devoted to each of the classes that variations would have been hard.

Sometimes the most reasonable option is to beat a hasty retreat.

Dark Heart of Uukrul features a very advanced save system, arguably the most optimal to this day. Through the game the party comes across sanctuaries, acting as places to save and rest. These act as checkpoints, but you can also save anywhere between sanctuaries, even though those saves are overridden upon entering combat and character deaths. What was the philosophy behind the save system?

Ian Boswell: Personally, I was never comfortable with the approach most computer RPGs take, where if a character dies you just go back to a recent save, then carry on as if nothing happened. I thought death should matter. It should be a setback. If you can erase your mistakes that easily, it encourages reckless play. Similarly, winning a difficult encounter becomes no great reward.

Initially, I wanted to have no save/restore facility at all, just save/resume. If you lose a character, he/she is gone for good. You can get a new character of similar level to join your party but the dead one stays dead. Broderbund vetoed that idea, and they were right.

So we came up with the Sanctuary system, and it’s a really good balance between having a save/restore facility, and still having a strong incentive to keep your characters alive.

Martin Buis: Unfortunately, we had to add copy protection to the game as well. We were somewhat resistant to this, and at least wanted it to feel as though it was part of the story. We added the soul amulets at each sanctuary to enforce that – it was better that a more invasive scheme that would require a password on each game startup.

Initially, I wanted to have no save/restore facility at all, just save/resume. If you lose a character, he/she is gone for good. You can get a new character of similar level to join your party but the dead one stays dead. Broderbund vetoed that idea, and they were right.

So we came up with the Sanctuary system, and it’s a really good balance between having a save/restore facility, and still having a strong incentive to keep your characters alive.

Martin Buis: Unfortunately, we had to add copy protection to the game as well. We were somewhat resistant to this, and at least wanted it to feel as though it was part of the story. We added the soul amulets at each sanctuary to enforce that – it was better that a more invasive scheme that would require a password on each game startup.

The idea to present the plot via apparitions (or visions) of Mara is as memorable as it is rare. Personally, I can only recall one other 1980s CRPG that did something similar: Tower of Myraglen (1987) by Richard Seaborne. Were you aware of that game? Why did choose to go for this kind of presentation?

Ian Boswell: I’ve not heard of that game, and we predate it anyway. Maybe he copied us! Mara is introduced early on in the plot as an explorer who has gone before, and therefore knows secrets about what lies ahead. There was no sensible way the party could actually meet Mara – but seeing visions of her allows her to appear anywhere. She moves the plot forward, and gradually reveals clues about the whole story. We made sure the story surrounding Mara was intriguing enough, that we could have built a sequel around it, but the sequel never happened.

Martin Buis: We wanted to have a guide pulling the characters through the game, and Mara provided an emotional attachment to the quest that tied together the background and ultimate challenge. Again, we wanted the game to feel real-time, so the idea of Mara appearing and disappearing quickly strengthened that, and increased the tension in the gameplay. When we were designing we’d get to the point where we wanted to make something special like Mara and we’d have to think about how to do it, because of the limitations. Invariably I would ask Ian for something over the top, and he’d say it would be hard to pull off with these constraints; we’d work out a compromise, he’d over-deliver on the coding and the end result would be great!

Martin Buis: We wanted to have a guide pulling the characters through the game, and Mara provided an emotional attachment to the quest that tied together the background and ultimate challenge. Again, we wanted the game to feel real-time, so the idea of Mara appearing and disappearing quickly strengthened that, and increased the tension in the gameplay. When we were designing we’d get to the point where we wanted to make something special like Mara and we’d have to think about how to do it, because of the limitations. Invariably I would ask Ian for something over the top, and he’d say it would be hard to pull off with these constraints; we’d work out a compromise, he’d over-deliver on the coding and the end result would be great!

Dark Heart of Uukrul had some very basic graphics. Personally I did not mind that, but what did that have to do with?

Ian Boswell: The graphics weren’t too bad for the era when it was released. If we could have finished the development a year earlier, the graphics would have been really good by comparison with then-current releases. But it’s true that the standard of gaming graphics kept improving, as did the graphics hardware and libraries available to support it. So now it does look really simplistic. If we had produced a sequel I think we would have needed to hire a professional graphic artist.

Martin Buis: Broderbund helped us out with the larger artwork, but we did all the character animations, level artwork ourselves. The limitations of the platform were part of what made the visual appeal, ahem, spare, but a lot of it was my limitation as an artist as well. At the same time, Moore’s law was really changing the expectations of what was available in a gaming platform and we didn’t have the resources as a small team to make the graphics brilliant – we prioritized the gameplay, puzzles and size of the levels over that, since we believed the real game would still be played in the imagination of the user.

Martin Buis: Broderbund helped us out with the larger artwork, but we did all the character animations, level artwork ourselves. The limitations of the platform were part of what made the visual appeal, ahem, spare, but a lot of it was my limitation as an artist as well. At the same time, Moore’s law was really changing the expectations of what was available in a gaming platform and we didn’t have the resources as a small team to make the graphics brilliant – we prioritized the gameplay, puzzles and size of the levels over that, since we believed the real game would still be played in the imagination of the user.

Can you talk a bit about the development process? How long did it take you, and what were the main challenges involved?

Ian Boswell: Going from memory here, we were a couple of years at it spare time, while completing University studies, and I spent a year working on it more solidly after that, during which we got signed by Broderbund, so then we had to finish it. But it took more than a year after that. I think challenges we faced were that you had to code everything yourself back then (even wrote our own graphic library in assembler so it would be fast enough), and we had to fit the entire game onto two floppy disks.

Martin Buis: Broderbund paid an advance on the Apple version, and we agreed to produce an IBM port, so we put some of that money into ‘hiring’ a couple of our college friends to work on the port. Overall, the process took many years across those two platforms. I shudder to think what the hourly rate would have been!

There were a lot of changes that occurred during the development process. We had laid out the basic story, and implemented much of the game engine, but kept trying to do new things with that platform. It seemed like the game was largely complete for a long time while we added features that our playtesting found or that Broderbund requested. For example, the automap function was added relatively late in the process. Perhaps a more focused vision would have helped that, but the gaming market was moving quite quickly as we were completing the game, so there was an element of proactive catch-up, if that makes any sense.

Martin Buis: Broderbund paid an advance on the Apple version, and we agreed to produce an IBM port, so we put some of that money into ‘hiring’ a couple of our college friends to work on the port. Overall, the process took many years across those two platforms. I shudder to think what the hourly rate would have been!

There were a lot of changes that occurred during the development process. We had laid out the basic story, and implemented much of the game engine, but kept trying to do new things with that platform. It seemed like the game was largely complete for a long time while we added features that our playtesting found or that Broderbund requested. For example, the automap function was added relatively late in the process. Perhaps a more focused vision would have helped that, but the gaming market was moving quite quickly as we were completing the game, so there was an element of proactive catch-up, if that makes any sense.

Dark Heart of Uukrul isn't particularly ashamed of its difficulty.

Can you describe the reception the game got and your reaction to it? In retrospect, would you have changed anything about the game? Is there anything you would have done differently?

Ian Boswell: When Broderbund signed us up, there was a window where computer RPGs were hot property, but the window didn’t stay open long enough. It took us too long to complete the game, and I’d say we missed the market by 6-12 months. Broderbund published it, but by then RPGs were “last year’s model”. They did little to promote or advertise the game, and it sold only modestly, something around 5,000 copies.

The reception from the public however, from the few people that actually know about the game, has always been really positive. Even now 25 years later, I still get an occasional email from somebody telling me how much they enjoyed the game, especially the puzzles!

Martin Buis: We had aimed at beating the technical sophistication of Wizardry when we started, but it was a moving target and by the time we delivered we were a little behind the start of the art. I think that the lack of sound was probably a big factor in the game being overlooked in the market place. About the time Uukrul came out Id released Wolfenstein, and everyone’s expectations of what you could do with computers changed. Really, the whole genre of thoughtful games seems to have disappeared, and casual gaming seems to be pushing things further down the ‘stateless’ approach to gaming.

At the time the gaming industry still felt like a cottage industry, and we were in New Zealand as Ian mentioned, which was a long way away from San Rafael where Broderbund were located. Looking back, it would have been better to have had more resources around to accelerate development, but since the market as a whole was changing, that wouldn’t have made a big difference.

The reception from the public however, from the few people that actually know about the game, has always been really positive. Even now 25 years later, I still get an occasional email from somebody telling me how much they enjoyed the game, especially the puzzles!

Martin Buis: We had aimed at beating the technical sophistication of Wizardry when we started, but it was a moving target and by the time we delivered we were a little behind the start of the art. I think that the lack of sound was probably a big factor in the game being overlooked in the market place. About the time Uukrul came out Id released Wolfenstein, and everyone’s expectations of what you could do with computers changed. Really, the whole genre of thoughtful games seems to have disappeared, and casual gaming seems to be pushing things further down the ‘stateless’ approach to gaming.

At the time the gaming industry still felt like a cottage industry, and we were in New Zealand as Ian mentioned, which was a long way away from San Rafael where Broderbund were located. Looking back, it would have been better to have had more resources around to accelerate development, but since the market as a whole was changing, that wouldn’t have made a big difference.

After Dark Heart of Uukrul, you do not seem to have worked on any other video game. Why did you decide to leave the industry behind, and what have you been involved with since then?

Ian Boswell: I wouldn’t say Martin and I were ever in the industry. It was a spare time project, created on a shoestring budget, and something we can look back on, proud to have completed it. As a business proposition it would have been an utter failure. I think I estimated once that our time engaged on this project had yielded us income of about $2 an hour.

So I guess there was never any chance of doing a second game, unless the first one had been much more successful. The first one was done for fun and for pride. The second one would have to be a business proposition.

I’m still in the software industry. I now manage a small custom software company, made up of other people who are better at coding than I ever was. One of my business partners is Francois Pirus, who I met through Uukrul. He helped us with coding one of the platform ports. We don’t write games though. The games industry now requires huge budgets, huge teams and huge risk. You couldn’t image a major title coming from two guys working in their spare time.

But, interestingly, that could change with mobile platforms. It is conceivable that a game which is simple but ingenious could become a hit as a mobile platform app.

Martin Buis: I have stayed in technology also, though I’m not in the gaming industry. I enjoy looking at new games for their mechanics and story, so I buy quite a few games. I’ve enjoyed Portal and Minecraft over the last few years, the first for the story and the second for the community.

I finished my degree in Comp Sci with an AI major (which would have suited me for games, had I graduated a decade later), but took that into finance. Incidentally, one of the AI ideas under the surface of Uukrul was the character generation mechanism, which was influenced by expert systems work. While my day-to-day work is pretty hands-off these days, I enjoy coding as a side project, and noodle around with Objective-C. My kids are obsessed by Minecraft and want to be game designers, so that’s a pretty sad indictment.

So I guess there was never any chance of doing a second game, unless the first one had been much more successful. The first one was done for fun and for pride. The second one would have to be a business proposition.