- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 100,143

Tags: Brian Fargo; Interplay; The Digital Antiquarian

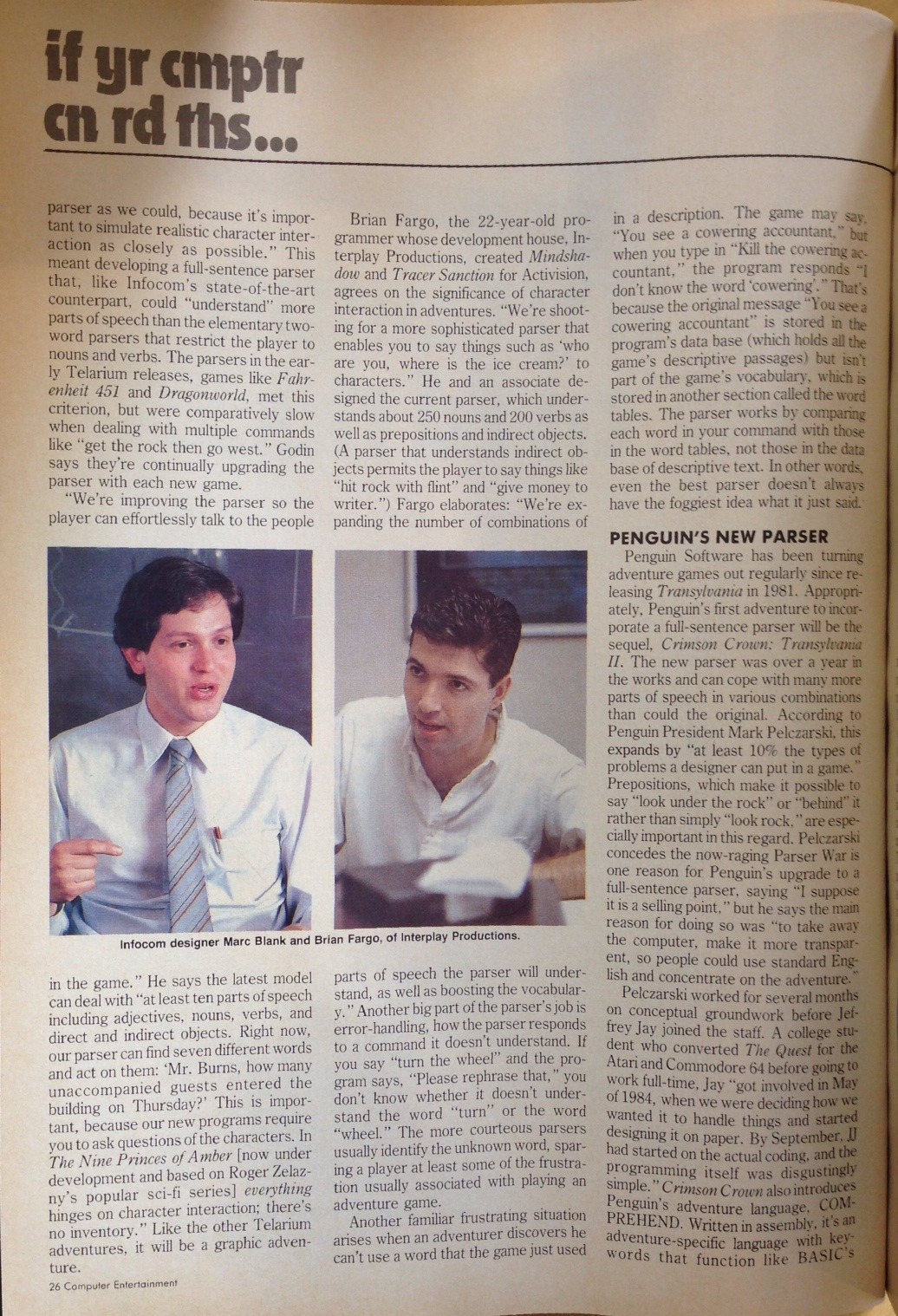

In his earlier article about the decline of the Wizardry series in the 1980s, Jimmy Maher of The Digital Antiquarian briefly discussed the success of Interplay's The Bard's Tale during those years. Today, the Antiquarian has published an entire post dedicated to chronicling the rise of Interplay under Brian Fargo. In addition to a recapping of the story of The Bard's Tale series, special attention is paid to Interplay's now mostly forgotten adventure games, which were published by Activision. Here's an excerpt:

"Electronics Arts...were eager to diversify into more hardcore genres like the CRPG". The past is indeed a foreign country.

In his earlier article about the decline of the Wizardry series in the 1980s, Jimmy Maher of The Digital Antiquarian briefly discussed the success of Interplay's The Bard's Tale during those years. Today, the Antiquarian has published an entire post dedicated to chronicling the rise of Interplay under Brian Fargo. In addition to a recapping of the story of The Bard's Tale series, special attention is paid to Interplay's now mostly forgotten adventure games, which were published by Activision. Here's an excerpt:

Fargo and his old high-school buddy Michael Cranford had been dreaming of doing a CRPG since about five minutes after they had first seen Wizardry back in 1981. Cranford had even made a stripped-down CRPG on his own, published on a Commodore 64 cartridge by Human Engineered Software under the title Maze Master in 1983 to paltry sales. Now Fargo convinced him to help his little team at Interplay create a Wizardry killer. It seemed high time for such an undertaking, what with the Wizardry series still using ugly monochrome wire frames to depict its dungeons and monsters and available only on the Apple II, Macintosh, and IBM PC — a list which notably didn’t include the biggest platform in the industry, the Commodore 64. Indeed, CRPGs of any sort were quite thin on the ground for the Commodore 64, decent ones even more so.

[...] Soon the game was far enough along for Fargo to start shopping it to publishers. His first stop was naturally Activision. One of Jim Levy’s major blind spots, however, was the whole CRPG genre. He simply couldn’t understand the appeal of killing monsters, mapping dungeons, and building characters, reportedly pronouncing Interplay’s project “nicheware for nerds.” And so Fargo ended up across town at Electronics Arts, who, recognizing that Trip Hawkins’s original conception of “simple, hot, and deep” wasn’t quite the be-all end-all in a world where all entertainment software was effectively “nicheware for nerds,” were eager to diversify into more hardcore genres like the CRPG. EA’s marketing director Bing Gordon zeroed in on the appeal of one of Cranford’s relatively few expansions on Wizardry, the character of the bard. He went so far as to change the game’s name from Shadow Snare to The Bard’s Tale to highlight him, creating a lovable rogue to serve as the star of advertisements and box copy who barely exists in the game proper: “When the going gets tough, the bard goes drinking.” Beyond that, promotingThe Bard’s Tale was just a matter of trumpeting the game’s audiovisual appeal in contrast to the likes of Wizardry. Released in plenty of time for Christmas 1985, with all of EA’s considerable promotional savvy and financial muscle behind it, The Bard’s Tale shocked even its creators and its publisher by running neck-and-neck in sales for months with the long-awaited Ultima IV that appeared just a few weeks later. Interplay had come into the big time; Fargo’s days of scrabbling after any work he could find looked to be over for a long, long time to come.

The inevitable Bard’s Tale sequel was completed and shipped barely a year later. Another solid hit at the time on the strength of its burgeoning franchise’s name, it’s generally less fondly remembered today by fans. It seems that Michael Cranford and Fargo had had a last-minute falling-out over royalties just as the first Bard’s Tale was being completed, which led to Cranford literally holding the final version of the game for ransom until a new agreement was reached. A new deal was brokered in the nick of time, but the relationship between Cranford and Interplay was irretrievably soured. Cranford was allowed to make The Bard’s Tale II: The Destiny Knight, but he did so almost entirely on his own, using much of the tools and code he and Interplay’s core team had developed together for the first game. The lack of oversight and testing led to a game that was insanely punishing even by the standards of the era, one that often felt sadistic just for the sake of it. Afterward Cranford parted company with Interplay forever to study theology and philosophy at university.

Despite having rejected The Bard’s Tale themselves, Activision was less than thrilled with Interplay’s decision to publish the games through EA, especially after they turned into exactly the sorts of raging hits that they desperately needed for themselves. Fargo notes that Activision and EA “just hated each other,” far more so even than was the norm in an increasingly competitive industry. Perhaps they were just too much alike. Jim Levy and Trip Hawkins both liked to think of themselves as hip, with-it guys selling the future of art and entertainment to equally hip, with-it buyers. Both were fond of terms like “software artist,” and both drew much of their marketing and management approaches from the world of rock and roll. Little Interplay had a tough task tiptoeing between these two bellicose elephants.

[...] By 1987, then, Brian Fargo had established his company as a proven industry player. Over many years still to come with Fargo at the helm, Interplay would amass a track record of hits and cult touchstones that can be equaled by no more than a handful of others in gaming’s history. They would largely deliver games rooted in the traditional fantasy and science-fiction tropes that gamers can never seem to get enough of, executed using mostly proven, traditional mechanics. But as often as not they then would garnish this comfort food with just enough innovation, just enough creative spice to keep things fresh, to keep them feeling a cut above their peers. The Bard’s Tale would become something of a template: execute the established Wizardry formula very well, add lots of colorful graphics and sound, and innovate modestly, but not enough to threaten delicate sensibilities. Result: blockbuster. The balance between commercial appeal and innovation is a delicate one in any creative field, games perhaps more than most. For many years few were better at walking that tightrope than Interplay, making them a necessary perennial in any history of games as a commercial or an artistic proposition. The fact that this blog strives to be both just means they’re likely to show up all that much more in the years to come.

[...] Soon the game was far enough along for Fargo to start shopping it to publishers. His first stop was naturally Activision. One of Jim Levy’s major blind spots, however, was the whole CRPG genre. He simply couldn’t understand the appeal of killing monsters, mapping dungeons, and building characters, reportedly pronouncing Interplay’s project “nicheware for nerds.” And so Fargo ended up across town at Electronics Arts, who, recognizing that Trip Hawkins’s original conception of “simple, hot, and deep” wasn’t quite the be-all end-all in a world where all entertainment software was effectively “nicheware for nerds,” were eager to diversify into more hardcore genres like the CRPG. EA’s marketing director Bing Gordon zeroed in on the appeal of one of Cranford’s relatively few expansions on Wizardry, the character of the bard. He went so far as to change the game’s name from Shadow Snare to The Bard’s Tale to highlight him, creating a lovable rogue to serve as the star of advertisements and box copy who barely exists in the game proper: “When the going gets tough, the bard goes drinking.” Beyond that, promotingThe Bard’s Tale was just a matter of trumpeting the game’s audiovisual appeal in contrast to the likes of Wizardry. Released in plenty of time for Christmas 1985, with all of EA’s considerable promotional savvy and financial muscle behind it, The Bard’s Tale shocked even its creators and its publisher by running neck-and-neck in sales for months with the long-awaited Ultima IV that appeared just a few weeks later. Interplay had come into the big time; Fargo’s days of scrabbling after any work he could find looked to be over for a long, long time to come.

The inevitable Bard’s Tale sequel was completed and shipped barely a year later. Another solid hit at the time on the strength of its burgeoning franchise’s name, it’s generally less fondly remembered today by fans. It seems that Michael Cranford and Fargo had had a last-minute falling-out over royalties just as the first Bard’s Tale was being completed, which led to Cranford literally holding the final version of the game for ransom until a new agreement was reached. A new deal was brokered in the nick of time, but the relationship between Cranford and Interplay was irretrievably soured. Cranford was allowed to make The Bard’s Tale II: The Destiny Knight, but he did so almost entirely on his own, using much of the tools and code he and Interplay’s core team had developed together for the first game. The lack of oversight and testing led to a game that was insanely punishing even by the standards of the era, one that often felt sadistic just for the sake of it. Afterward Cranford parted company with Interplay forever to study theology and philosophy at university.

Despite having rejected The Bard’s Tale themselves, Activision was less than thrilled with Interplay’s decision to publish the games through EA, especially after they turned into exactly the sorts of raging hits that they desperately needed for themselves. Fargo notes that Activision and EA “just hated each other,” far more so even than was the norm in an increasingly competitive industry. Perhaps they were just too much alike. Jim Levy and Trip Hawkins both liked to think of themselves as hip, with-it guys selling the future of art and entertainment to equally hip, with-it buyers. Both were fond of terms like “software artist,” and both drew much of their marketing and management approaches from the world of rock and roll. Little Interplay had a tough task tiptoeing between these two bellicose elephants.

[...] By 1987, then, Brian Fargo had established his company as a proven industry player. Over many years still to come with Fargo at the helm, Interplay would amass a track record of hits and cult touchstones that can be equaled by no more than a handful of others in gaming’s history. They would largely deliver games rooted in the traditional fantasy and science-fiction tropes that gamers can never seem to get enough of, executed using mostly proven, traditional mechanics. But as often as not they then would garnish this comfort food with just enough innovation, just enough creative spice to keep things fresh, to keep them feeling a cut above their peers. The Bard’s Tale would become something of a template: execute the established Wizardry formula very well, add lots of colorful graphics and sound, and innovate modestly, but not enough to threaten delicate sensibilities. Result: blockbuster. The balance between commercial appeal and innovation is a delicate one in any creative field, games perhaps more than most. For many years few were better at walking that tightrope than Interplay, making them a necessary perennial in any history of games as a commercial or an artistic proposition. The fact that this blog strives to be both just means they’re likely to show up all that much more in the years to come.

"Electronics Arts...were eager to diversify into more hardcore genres like the CRPG". The past is indeed a foreign country.