Although Brazil is a huge country that is recognized worldwide, foreigners know very little about us beside the usual Carnaval, Football, Caipirinha & Bossa Nova (ok, and big butts) cliches.

Which is sad, as our myths and culture offer a refreshing change from done-to-death themes and settings we see in gaming. I never saw a game making good use of our art, music, beliefs and folklore, of legends like the Saci, Mula-sem-Cabeça, Caipora, Boitatá, Curupira and many others.

Hell, we even have a "ancient mysterious language" in the form of Tupi-Guarani, a language spoken by natives that has woven itself into our own Portuguese, distancing us from Portugal. Many Brazilian words come from Tupi, especially names - sometimes with surprising meanings.

Ipanema, for example, is the name of one of the most well-known beaches in Rio de Janeiro (and that one song everyone knows). Few know that Ipanema actually means "bad water" in Tupi-Guarani.

Of course, having a rich, original culture that no one else using it is a great opportunity to impress people with charming and exotic titles, like

Xilo, an award-winning 2011 indie game prototype:

Xilo is EXTREMELY Brazilian, in almost every aspect possible.

The visual style (based on local woodcut art), the soundtrack (baião), the enemies (all from our folklore, like the Mula Sem Cabeça - a headless flaming mule), the main character (a cangaçeiro), the poems (cordel literature), the enviroment (sertão, a semi-arid region in northeastern Brazil), etc...

It's a game by Brazilians, for Brazilians, as few people outside our borders can understand or relate to what's going on. Sadly, games such strong and "exotic" cultural tones often devolves into a curiosity, an oddity - not a "real" game. It's first A Brazilian Game (wow!), second a platformer.

The spiced giant robot

Koichi Iwabuchi is a Japanese scholar, famous for coning the expression "mukokuseki" - or "Culturally Odorless" - to describe how Japanese exports like Walkmans, Anime and Video Games were easily accepted worldwide. He claims it was because they didn't carry strong Japanese cultural values that could put off foreigners - what he calls "Cultural Odor".

While it was true decades ago, with Mario,

Dragon Quest, Castlevania, Astroboy and even

Pokémon, it's a bit harder to look at modern JRPGs, Animes and Mangas and say the same thing.

Thus, to me a more relevant concept is his theory about the opposite phenomena - the moment when this "Cultural Odor" become a "Cultural Fragrance", adding to the appeal of the product.

It's obvious that this appeal is very restricted. Saying a game is from Japan can create high expectations depending on the audience, but saying a game is from Brazil usually results in lines like "are there even computers in Brazil?", or an aversion to an unusual culture they don't understand.

Xilo, as mentioned

above, is a game with a heavy "odor", not a "fragrance".

However, each culture has its own particularities, that unique way of doings things that cannot be easily described. It's not an odor nor a fragrance, that you immediately say "oh, this is definitely Japanese!", but a subtle, unusual element you can't describe at first. An exotic spice.

I believe that

Chroma Squad, a tactical RPG inspired by Japanese tokusatsu shows, has such "spice":

Chroma Squad is also unmistakably Brazilian, but probably only to Brazilians.

You see, the "Inspired by Saban's

Power Rangers™" disclaimer that was legally forced into the game is rather untrue. While most countries only became aware of Japanese tokusastu shows with

Power Rangers in 1993, Brazil has a long history with them. Tokusastu shows came as early as 1964 with

National Kid, which was a huge success here - even thought it flopped in Japan.

Since then, countless similar shows aired here, like

Ultraman, Specterman, Lionman, Changeman, Jiraya, Kamen Rider, Cybercops, etc... all on national TV, with a large audience and tie-in products like toys,

music albums and even

circus shows. And they weren't like

Power Rangers, remade with local actors - they had Japanese actors, locations and theme songs (plus poorly translated dialogs).

Chroma Squad also has an unique humor, influenced by local shows like

Os Trapalhões and an icon of Latin America:

El Chavo del Ocho - a show from the 70's that still reprises here every day.

These elements and influences are felt in the game, in its jokes, references and dialog, but it doesn't become an "odor" that puts off foreigners - like if it was based on Capitão 7, a Brazilian hero no one ever heard about. Rather, it's a global game with a distinct "spice" that could only be produced here. Only in Brazil you would have this unique cultural mishmash of "low-budget" casual humor,

theme songs sang in Japanese (like

the tokusatus that aired here, not like

Power Rangers) and monsters designed after SpongeBob SquarePants, Teletubbies and Pop-Up Pirate.

It's a subtle way of "leaking" our culture into the world, our humor, references and way of seeing things, even if under the guise of Japanese Tv shows. Eventually this can evolve and become a "fragrance", perhaps with people associating Brazil with an unique brand of humor, tone or theme - like how you know Russian games usually have a dry, bleak and desolate tone.

And there are more subtle and unexpected places this "spice" appears... like in alleys.

Alleys of the World

This is an alley from Detroit:

I saw this countless times in movies, games, video clips and news. It has the iconic fire stairs, trash cans, graffiti and dark, decaying "Batman parents died here" atmosphere.

Yet, for most of my life, this was alien to me. You see, here in São Paulo we don't have alleys like those, our buildings are either all built side-by-side or they have walls around them. We also don't have fire stairs. And we usually deposit our trash in the front of our buildings.

Alleys in São Paulo are entirely different. Here, they are either narrow passageways in favelas, or (extremely rare) small streets on the backside of walled houses, like these:

So I had never seen an alley like the one in Detroit until I traveled to the US, already in my mid-20s.

Why is this relevant? Because if you asked me to design a Detroit-style alley for a game, I would be very confused. Are these really the norm or just a cliche? Are they really dangerous? How long are they? Where those locked doors lead to? Are they usually this decayed? Can you park cars there? Can you drive across them? Do kids play there? How do you drop down the fire stairs? Does it go all the way up to the roof? Who collects the trash, how and when?

Of course, I can google or ask locals. But these things are tricky. There might be particularities I'm not even aware of, leading to incorrect assumptions and, as result, a design that feels off.

Take for example

Resident Evil 3: Nemesis. Now,

Resident Evil is a Japanese franchise, but the fictional Raccoon City is located in the US mid-west. Knowing that, take a look at this alley:

Does this look anything like the one in Detroit, or like any alley you've ever seen? Not to me, it didn't.

That is, until I had the chance to travel to Japan in 2012 and roam through the alleys of Tokyo:

It immediately clicked. I

felt in one of those

RE3 alleys. More than just the visual resemblance, it had the narrow passageway, the claustrophobic dark ambiance, the feeling that the top of the buildings had closed on themselves and swallowed the sky. And the bicycles, left without locks.

Although the

RE team was extremely talented and probably did a lot of research on American cities and their layouts, they could not avoid leaking their own culture and experience into the gaps.

Is this a bad thing? Not really,

Resident Evil 3 is a zombie game, set in a fictional city, where mega-corporations can send biological weapons to massacre the population... perfectly accurate portrayal of US architecture isn't a key feature here.

I'd say it's actually a plus, an unique "spice" the game has, that makes the streets and alleys feel threatening and "wrong", in a way you can't really explain.

Gauchos & their Mexican food

Another game I would like to mention is

Max Payne 3. Famously, it's set in São Paulo, and this time the location plays a vital role in the plot, as Max doesn't speak Portuguese nor the game offers subtitles to the Portuguese dialogs, so both Max and the players feel lost in a foreign country.

There was a lot of outrage from Brazilians over

Max Payne 3. First, Rockstar said São Paulo has "famous for its hot weather and funk music". That's Rio de Janeiro, amigo.

Then came things like hiring Portuguese actors to voice Brazilian characters, a "Gauchos" restaurant serving Mexican food and some VERY weird uses of our local folklore, among other bizarre things.

These little details all combined to create a São Paulo that, although had a skyline just like the one I see now looking through my window, doesn't feel like the city I live in.

A few weeks ago, Daniel Várvra wrote

an article about how he wants

Kingdom Come: Deliverance to be as authentic as possible, since it was never done before and foreigners will never be able to do it:

As a Czech, most foreign games and movies set in my own country seem to me at best ridiculous, because foreigners can’t even manage to capture properly the look of this country (Call of Duty, Metal Gear Solid 4, Forza 5 etc.), never mind our mentality and culture.

I agree with him, gringos tempering with my culture led to things like

Street Fighter's Blanka and

a soup-opera where a woman gives birth to a Curupira (a mythic guardian of the forests). It's a mess! But I think it's an entertaining, unique and "spicy" mess, that could never be created otherwise.

A surprising example of this is

Max Payne 3's Chapter 10. Most of the game is spent on favelas or inside warehouses, garages and stadiums (or an airport train that really should, but does not exist). The only time in the entire game you visit downtown São Paulo is when you go to a bus graveyard.

"What the hell? Why didn't they use the Paulista Avenue or Mercadão instead of making shit up?!" said I while playing, before googling it and finding out that yes, São Paulo has a bus graveyard:

I was born in São Paulo, I lived here most of my life. Yet I saw things I had never seen before in a game made by foreigners that don't even speak Portuguese and only visited for a few days - precisely because they didn't live here and didn't care for its traditional landmarks.

Like Vávra, I still wish to see "my São Paulo" in a game, with all the quirks and locations only a local knows. But that doesn't mean I can't enjoy the São Paulo that Rockstar portrayed, the vistas they chose to show and design choices such as the bold "no subtitles" approach they went with.

Max Payne 3 is a game set in São Paulo that no one who lives in São Paulo could ever create. Here Rockstar found a foreign location to tell their story, players got lost in a foreign land and I saw my hometown portrayed and experienced through their foreign eyes, with a different flavor.

This is a healthy, interesting exchange, that bought something new to all of us.

All the Scotsman

I would love to see more of the culture of my country out there.

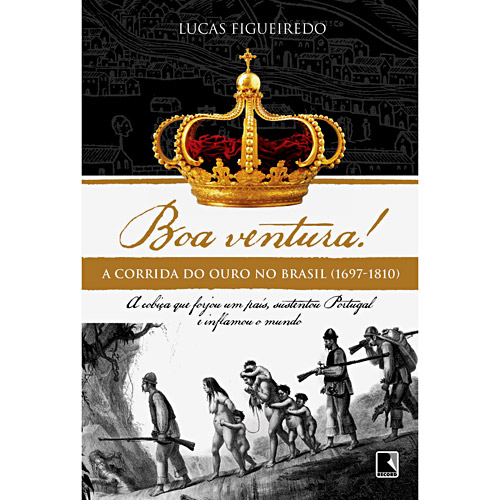

To see more people watching movies like

O Auto da Compadecida (aka

A Dog's Will), reading books like

Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands, listening to Raul Seixas (and not just

Garota de Ipanema), playing games based on the adventures of Cangaçeiros and Bandeirantes, of fugitive slaves and Italian immigrants, of 1864's imperial soldiers and 1964's anti-dictatorship rebels.

However, I don't think that's something only achievable by cramming those inside every game we make, or that it's something that only a True Born Son of Pátria Amada Brasil can help achieve.

Culture is a difficult thing to define, more even to limit. Trying to replicate the culture of others will certainly result in confusion and mistakes, with your own mentality, beliefs and experiences discreetly blending in though the gaps, no matter how hard you try to avoid it.

That would be an impossible barrier to surpass in a 100% accurate cultural and historical game, but most (none?) people aren't making those - they are trying to make interesting games.

As long as you aren't being racist or full of prejudice, then your take on a foreign culture can likely bring something new to the table, add some "spice" to the recipe, aiding both to you and those who you're borrowing from and allowing it to reach places and people it could never reach before.

Think of it as an unusual musical cover, like Pat Boone singing DIO:

Yeah, it's not a Metal song anymore, the heresy! But it will probably get at least a small smile from any metalhead, and it might even make your grandma get interested in what you're listening to. It speaks volumes of the quality of the song that someone so removed from the Heavy Metal scene would cover it, and the original will always be there for you to enjoy.

And so, I hope to one day play games about myths and traditions from Brazil, India, Korea, Nigeria, China, Poland, Mexico, Chile, etc... all made by locals, proudly showing their culture.

But I also eagerly await for the day I'll play a Brazilian RPG set in Medieval Poland, a Polish platformer set in Brazilian forests cities, an Indian RTS set in Greece, a Korean FPS set in the US, a Nigerian action game set in England and whatever other crazy combination anyone can come up with, with their cultures adding new elements to these games, spicing them up, offering new perspectives.

For this is the true richness of interacting with other cultures - not just telling your stories and hearing theirs, but bonding to create new ones. Or at least flavor them differently.

------------

PS: Just please stop with the monkeys roaming Brazilian streets, ok? That doesn't happen, I swear.

![Glory to Codexia! [2012] Codex 2012](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_slushfund2012.png)