On #Indiepocalypse:

What is really killing indie games

As you might have heard, indie games are heading towards the extinction, despite the fact that we’re now seeing more indie games released than ever.

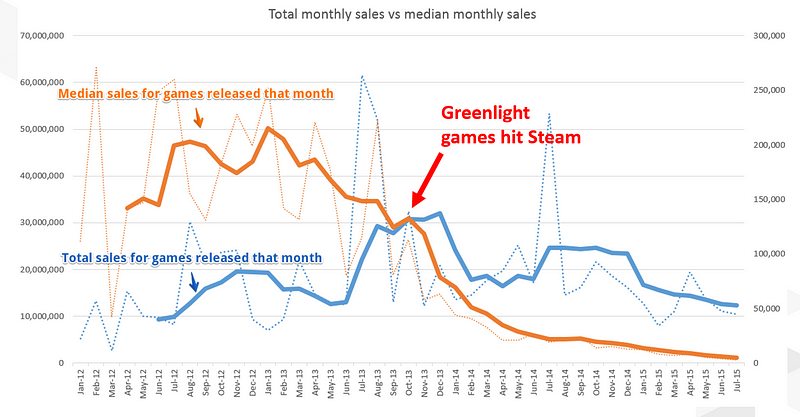

By now you’ve probably seen this graph a million times. It shows median ownership of games released each month on Steam in the last few years and as you can tell it has been dropping steadily since Greenlight introduction. Take a good look again, will you?

Ooh, scary!

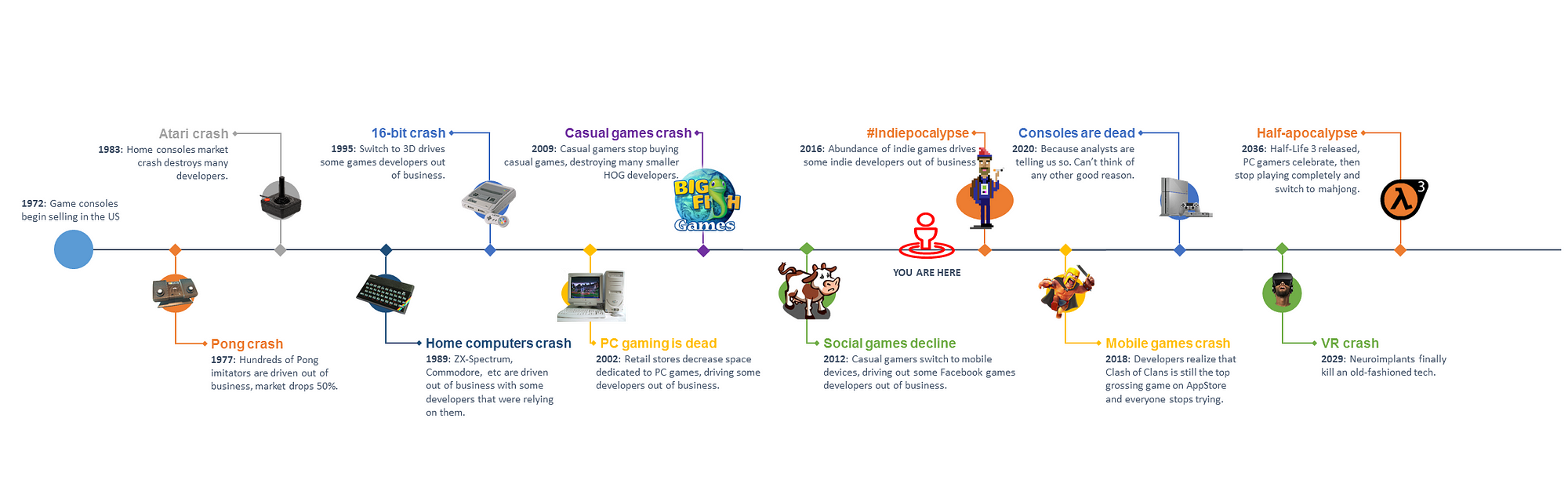

Is it the first time?

Games industry has been experiencing “apocalyptic events” every few years since the first Pong machines hit the market. In fact the first video games crash happened five years after this memorable date and was called “Pong crash” back then.

What happened is that many companies began to produce and sell their own Pong machines — clones of the original one. Market got flooded with the same games, competition became fierce and gamers (they didn’t call them gamers back then) got tired of Pong and went on to play something different. So, the overcrowded market of Pong machines crashed.

But the games industry, of course, didn’t.

In 1982 Atari, driven by incredible demand from stores, printed 2.5 million copies of movie tie-in game “E.T.”. Unfortunately for Atari, retail stores vastly overestimated the demand and sold only 1.5 million copies. Well, not “only” — 1.5M copies sold made E.T. the best selling game of 1982. Even today this number looks very impressive: GTA V for PC sold less in the same time frame.

But of course Atari had to eat the expense of the remaining 1 million copies and it was almost enough to sink the company. That’s why contracts between retail stores and game publishers have been changed to only allow for partial return of unsold copies.

But, again, games industry didn’t crash. In fact, 1983 was very healthy year for the game sales, and most developers in 1983 didn’t suspect that we’d later call this “The big video game crash”. Because it wasn’t neither big, nor crash at all.

After that apocalyptic events continued to wipe out gaming industry every few years. Remember home computers crash, when ZX-Spectrum and Commodore games just disappeared from stores? I do, I was a hobbyist developer back then, working on games for ZX-Speccy.

Then, of course, was death of 2D games heralded by the arrival of PlayStation and now infamous death of PC games, when in 2002–2005 many retail stores in US stopped selling those. That’s why we have Steam now, but back then it was apparent to every observer that PC games are no more and we should just move to whatever Nintendo has in store.

General gaming audience might have missed the death of casual games with the arrival of social networks, when older female audience stopped buying hidden object games about sexy vampires and moved on to farm virtual land in Facebook games. Those are dead now too — thanks Apple and Google, you’ve killed a whole industry!

And now we’re here, at the dawn of #Indiepocalypse, that is sure to wipe every indie game and replace them with Clash of Clans clones.

What causes this?

Mirko Ernkvist

detailed three key drivers that lead to changes like this. Of course, he wasn’t talking about Indiepocalypse, but all his three factors apply here as well.

Disruptive technology — Unity, Unreal and many other ready available professional-grade tools made developing games seem easy. Even my son managed to make a simple platforming game in Unity when he was 13 years old.

That leads us to the second horseman of the apocalypse —

low barrier of entry. Because everyone now has access to necessary tools and education, everyone can, theoretically, develop a game. It leads to the flood of aspiring game developers, trying to create something new.

The flood creates the third key driver —

lack of differentiation. How many retro-style action platformers do we really need? Do we actually want this many bad-looking games with fake “8-bit” graphics? I mean, some of them are good, brilliant even, but how can you hope to find a great game when they all look the same?

Are we facing unique challenges?

Now let me take a detour from all this apocalyptic talk for a bit and brag about my hobby.

I’m a photographer. I love taking pictures, I take my camera everywhere and my friends are kind enough to let me snap a photo or two when they’re doing something interesting.

I hate everything else about photography. I’ve stopped developing my film the moment Kodak labs arrived, I was one of the first people to switch to digital cameras at cost of the picture quality and I’m so lazy that I only use presets in Lightroom, never ever going into manual adjustments or trouble of launching Photoshop. I don’t even have it installed, despite buying it couple of years ago.

Oh, but I love the bragging part.

I’m not great, but I’m good enough, so you might have seen my pictures. Here are Anna Bashmakova and Sergey Orlovsky trying the first Oculus VR Dev Kit. Quick snaps, but press seems to use these pictures a lot.

Fun fact: Anna isn’t amazed by virtual reality on this photo. She is trying not to fall down, because Oculus isn’t plugged in yet.

I even sold some of my pictures and was printed in Forbes, Wired, Official PlayStation and on cover of Chinese edition of Chip (they haven’t paid a dime though).

But because I don’t treat my photography as a business, it can’t financially sustain me or my family. I like taking pictures, it’s a great rewarding hobby, but I would never dare to call myself an indie just because I’m not taking it seriously enough. I’m not an indie, I’m an amateur.

Now, ten years ago, when digital cameras started to popup in every single device available (mostly in mobile phones, of course) photography was doomed.

You’re complaining about 6 thousand developers on Steam?

Try competing with 2 billion photographers taking

tens of millions pictures every single day!

And, despite that, or, actually, thanks to that, professional photography strives. There are more professional photographers than ever and art of photography was elevated, leading us to better and more visually interesting pictures than fifty years ago.

Amateur or indie?

I would go as far as to claim that I’m taking better pictures than an average professional photographer back then — I have access to better tools and I’m building on the knowledge and practices those amazingly talented people established.

As an indie or, let’s face it, amateur developers, you also have access to better tools than Sid Meier or Richard Garriot had back then. And you are also building on works of titans, using forty years of great games as a foundation and inspiration for your own.

But you’re not competing against Sid Meier of 1986. You’re competing against him (and many other talented developers) in 2016, where everyone has access to the same tools, knowledge and distribution platforms.

The fact that your game is better than most games in 1984, 1994, 2004 or 2014 doesn’t mean anything. Your game has to be better than everything that is going to be released this year or, preferably, next year as well.

This little device has doomed an entire industry. Or didn’t.

Triple Indies

and other new terms

That is the reason I don’t buy into “triple indie” argument that suggest that indie developers have to become bigger and make more expensive games. I mean, it might be a sound strategy for some developers, but it’s not the only solution.

I think it boils down not to “Indie vs AAA” or to “Indie vs Triple-I vs AAA” but to “Hobby vs Business”.

Many indie developers love making games just for the sake of making games. They don’t want to do marketing, because it’s distracting, they don’t want to do financial planning, because it’s boring and they don’t like calculating ROI or analytics, because it’s not why they’ve started developing games.

And you know what? It’s fine. I’m one of those people when it comes to photography. I understand them and I’m doing exactly the same. But I’m not mistaking my lack of business approach to my hobby for the oppressive environment that’s killing my attempts to make money. I’m the one responsible for not making money on my photography, not 2 billion people with pocket cameras and smartphones and certainly not Google Image Search.

So if you don’t want to treat game development as any other business, don’t call yourself an indie. You’re an amateur and people like you are moving our industry forward, but you’re probably not going to make a lot of money (if any) doing so.

If you treat game development as a business, do your homework, research the market, talk to the press and plan your finances, you’re running a business. And then it doesn’t really matter if you’re one guy in his basement hiring freelancers when needed, or a full team. Because you know how much money you have to spend and earn so you don’t go out of business. You don’t have to become “Triple Indie” if you don’t need that many people or games that big to survive.

Of course, you still might fail as any other business might. But your chances of surviving will be way higher than for amateurs that aren’t treating business as expected and only here to have fun making games.

The discovery problem

Steam is no longer a discovery mechanism. And even when it was, it wasn’t really a good one, because it would only allow you to find handful of new games available on a single digital store. Do you think people could find League of Legends on Steam? But it didn’t stop Riot.

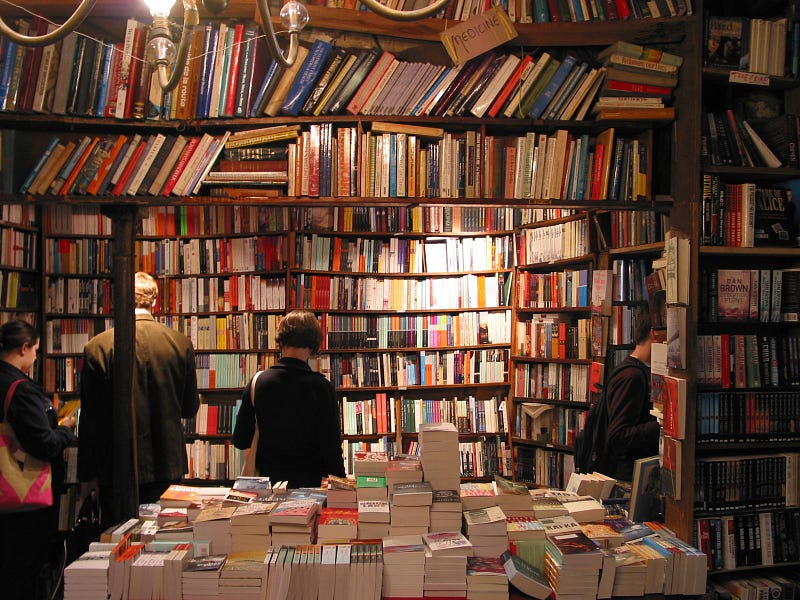

You shouldn’t treat Steam as your main promotional tool. It still could be useful in this regard, but Steam today is more like bookstore than classic games shop. When you walk into a bookstore, you wouldn’t probably be able to find a good book for you. I’ve just checked the bookstore nearby and all it had on “New and Top Selling” shelf were books about light spanking and bondage with young attractive millionaires and about surviving office politics. Both topics are probably related.

To buy a hard copy of “The Martian” by Andy Weir I had to walk to the back of the store and literally dig through hundred or so of sci-fi books. Works of Robert Heinlein, Arthur Clarke, and even Lee Harper for some reason are stacked in one place. You can’t find a book you want unless you know exactly what you’re looking for. That’s Steam today.

Seriously, this is Steam right now

Steam provides the means of selling the game and it also offers you some basic customer relations tools for free. But it by no means is a complete solution for game development, publishing and marketing and never claimed to be one.

So you’re left with your own means of marketing communications, which are plenty. Not only you have dozens of magazines, thousands of websites and blogs at your disposal, you also have access to hundreds of video programs — so called Youtubers. Imagine how hard it was getting your game in front of million viewers twenty years ago!

It’s not easy to market your game and it never was, but it’s now easier than ever: you no longer have to buy an expensive two-page advertisements in printed magazines or throw an all-expenses paid press events on Hawaii. Just get some of many thousands gaming enthusiasts with an audience interested in your game! If you can’t get any of them to pay attention to your game, why do you think gamers would?

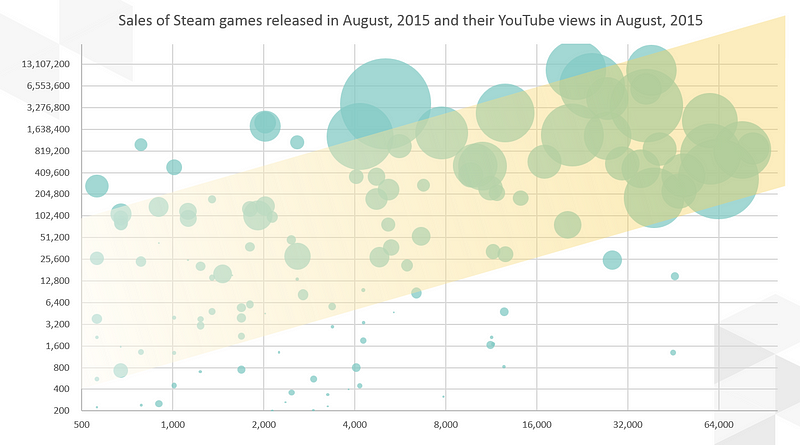

Here is a graph about Youtube views and game sales for all paid games released in August, 2015.

Please note that both scales on this graph are logarithmic

As you can see YouTube exposure strongly correlates with sales even in the first month after game release. The correlation becomes stronger as the time passes.

Of course, it might also mean that Youtubers are more likely to cover good games that are more likely to sell well.

Back to that scary graph

Remember that graph from the beginning of the article that you’ve seen a million times? I’m going to show it again, sorry.

I honestly have a point to prove here, just go with it

Now that we’re aware about difference between business and hobby, let’s take a look at top 10 selling games each month and what does it take to be at least #10 on Steam?

Not so scary now! Some falloff is attributed to recent games not being bundled yet

Hey, not so bad! It seems that nobody is dying and monthly top ten games aren’t affected by the influx of three hundred new games every month. Who would have thought?

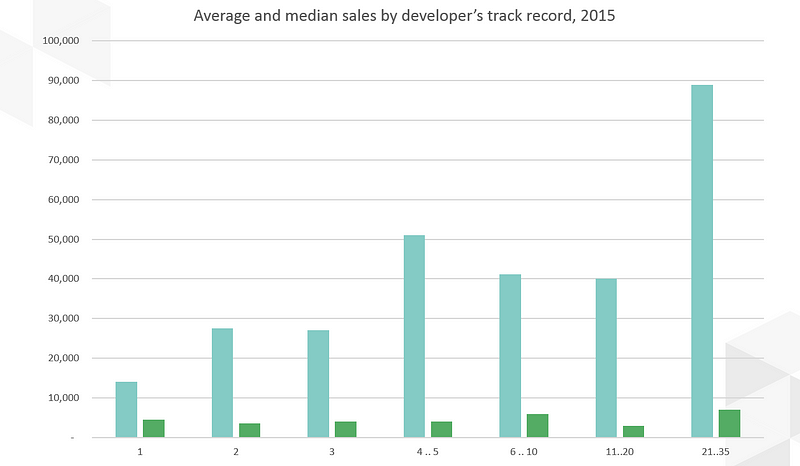

Let’s take a good look on developers entering the market vs developers creating their second or third game. Unsurprisingly developers with at least one game published on Steam, have better sales on average than newcomers. And this effect increases over time.

Of course we can’t tell who is treating their gaming company as hobby and who as a business.

But here is another finding — it doesn’t really matter if your first game sold a lot of copies or not. There is no correlation between the sales of the first game and chances of releasing the second one. All it matters is that you survive your first game, learn from it and have enough resources and willpower to continue.

It is harder for first games than before.

Yes, established developers have an advantage over newcomers. It’s true in every business environment — that’s why we have brands, loyalty programs, customer support and many other things that do not really help our first product (or the first sale), but lay a foundation for continued relationships with our clients.

Summary

So, what is really killing indie games and are they dying at all?

It would seem that the main culprit are indie games themselves.

The rising quality bar leads to more indie games failing, but it also leads to better games and that’s ultimately is what we’re here for — to create amazing experiences for our customers.

Steam did what everyone wanted — it stopped being Arstotzka-style border guard between game developers and gamers, allowing everyone to sell their games.

It was always your responsibility to create and market your game. You can’t expect some automated discovery algorithm or third-party service to just bring you money and fame. And while it is in fact harder marketing the games in the “holy 2013” way (put your game on Steam, receive money, brag on Twitter), it’s now possible to market your game in many other new ways that, of course, involve a lot of work.

If you want to stay in business of making games, you should treat it as business.

![Have Many Potato [2013] Codex 2013](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_potato2013.png)

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)