What Is Wyrdsong, the ‘Coming Together’ of RPG Houses Bethesda and Obsidian?

Fallout and Skyrim Veteran Jeff Gardiner tells us about his new RPG.

When Jeff Gardiner left Bethesda last year after 16 years working on games like Fallout 3, 4, 76, The Elder Scrolls: Skyrim, and Oblivion, he wasn’t doing so with the intent of starting his own studio. In fact, he didn’t know what he wanted to do.

Gardiner at first tried taking a break “to see if the fantasy of just playing games all day was going to be fulfilling,” but it wasn’t. He then interviewed for some high level roles at studios, and thought about consulting. None of that spoke to him.

At the time, Gardiner was also reading a book called First Templar Nation by Freddy Silva – an alternative history book about the origins of the Knights Templar, specifically in Portgual. Coincidentally, he had just visited many of the castles and locations mentioned in the book prior to the COVID-19 pandemic on a trip with his wife. As he continued to think along the lines of mythology, ritual, and the nature of reality, Gardiner found himself inspired.

Eventually, on the advice of a friend, he put together a pitch deck and began shopping around his new game idea. Netease bit, to the tune of $13.2 million. And thus Something Wicked Games was born – a studio collaboration between Gardiner and Obsidian veteran Charles Staples – to work on Gardiner’s idea: Wyrdsong.

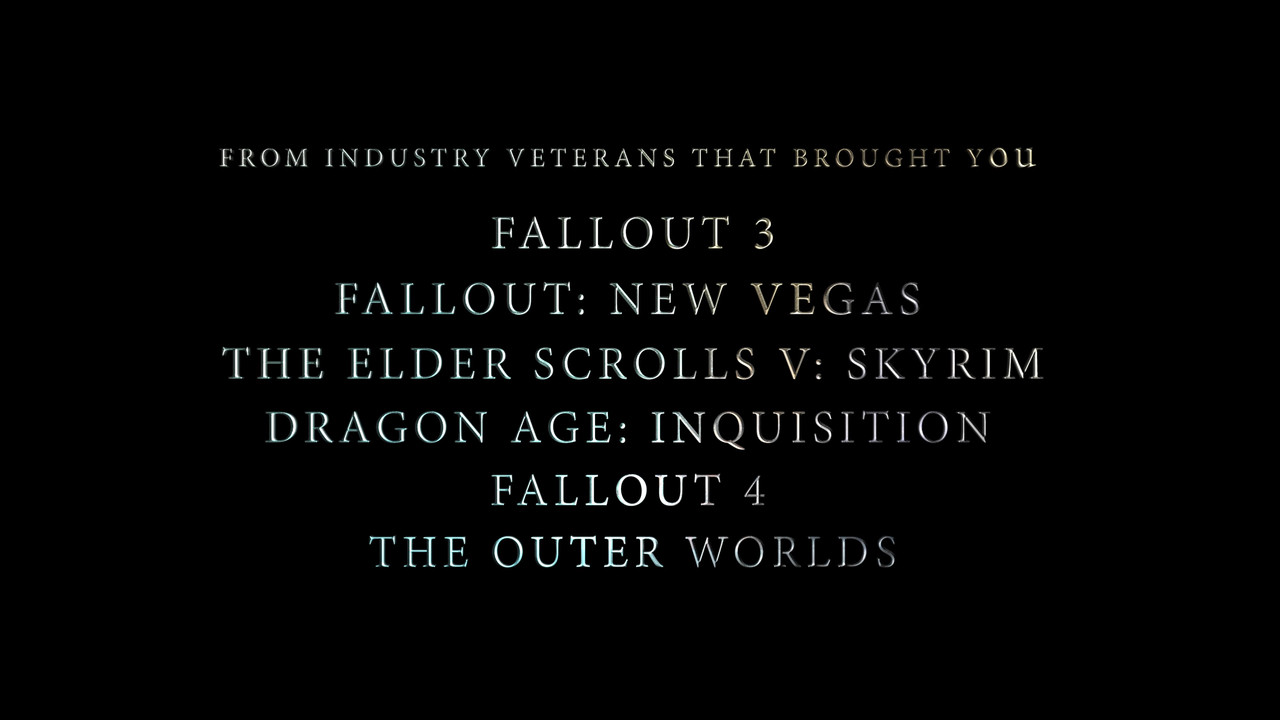

Wyrdsong is a “preternatural, occult, historical fantasy” game, and it’s going to be an open world RPG. It’s definitely single-player, no comment for now on multiplayer, and players can be “any race or gender” they want. It’s set in Portugal in the middle ages, and will explore themes around questioning the nature of reality, unreliable narrators, and the stories people tell themselves about their experiences. It is, he says, a “coming together of two great RPG houses” in its Bethesda and Obsidian DNA, and thus will include choices and consequences, Obsidian shades of grey, and in-depth dialogue trees. “We really want to have big, monumental elements you can only do in single-player games where you’re really affecting the world around you, and maybe other worlds as well,” Gardiner says.

But if between this description and the Opening Night Live teaser you still aren’t sure what Wyrdsong really

is, don’t worry. Gardiner isn’t 100% sure either, but that’s a good thing - it’s still quite early in development. Gardiner says that this very, very early development announcement is really more of a studio announcement for Something Wicked, but he wanted to “put a stake in the ground” in terms of the type of game he was making so he could attracted developers interested in helping him define more fully what Wyrdsong will be, collaboratively. He’s not interested in being an auteur.

“I don't want to have all these real detailed things that I can't wind back, or things that I am in love with and I can't get rid of. I want people to come and put their stamp on this game… I can give so many examples of my career where folks came in and just put things in the game that we didn't realize were there until we started playing it, or came to me with ideas that we moved the schedule around to make it accommodate. People got into this business and this job to have fun, right? They enjoyed making games, and I want to capture that spirit and excitement from people who've been doing it for a long time, but maybe don't still have that excitement and experience. Or new people. I'm really excited to bring some new people into this industry, and level them up, and share the joy that I've found here.”

There’s plenty of room to grow, too. At the moment, Something Wicked is only 13 people strong. Gardiner wants to aim for around 65-70 people, which he says is a “sweet spot” for making a compelling game that still lets everyone leave their mark on it. Helpfully, Something Wicked is fully remote, which Gardiner says is an approach he embraced following the COVID-19 pandemic – though he acknowledges it’s not necessarily an easy one in every respect.

“You have to be proactive in your approach to doing it,” he says. “If you just operate the way these studios have existed for the last 20 or 30 years, and assume those same things are true, I think you'll be in a lot of trouble in a full remote environment. I do think there might be difficulties with creative… There's people talking about watercooler moments, about getting to know people.

“Something Wicked Games is going to be very proactive in the fact that it is a remote-first culture. For instance, on Fridays, we're spending two hours just playing Valheim together right now, we're picking games. My concept artist is coming up with a Wyrdsong-themed [tabletop] RPG we're going to go through. This isn't about analyzing Valheim, it's about us coming together and chatting as we're playing a game. We plan on doing travel to get as many people together as possible over time, just here and there.”

Now that he’s in the driver’s seat, Gardiner is also interested in proactively building a certain kind of company culture: specifically, one that isn’t tied to the “milestones and requirements of larger organizations.” He recalls a time before Bethesda, he says, where he would often find himself on the hook for getting something done in a very timely, specific way, which he found “very onerous and difficult for the creative process.”

“I learned as a producer for years, that schedules are tools and they're guideposts, but they shouldn't be weaponized,” he says. “.I watched this talk by Steven Spielberg years ago, where he talked about the ‘crisis of faith’ that happens on every film. Despite the fact that he had the same crew and cast [on] every movie he's ever worked on, 80% of the way through, they're like, ‘What are we doing? How is this going to work?’ That happens in games too, but you have to walk through this stuff and get to the other side. It's about making smart, proactive decisions, listening to the people who are on the ground, making the content, not assuming you know things.”

Gardiner is candid that in this respect, as in all others, he’s learning as he goes. Though he’s run massive projects with up to 400 people involved before, it’s his first time running an entire studio. He’s in good company, too. Gardiner is the latest in a multi-year wave of game dev veterans who have left AAA companies such as

Bethesda,

Activision Blizzard,

Riot,

EA,

2K, and others to start their own ventures with smaller teams, big funding, and even bigger ideas. I ask Gardiner what he makes of the trend, and his own place within it.

“I think it's a combination of the times we're in, and the industry as a whole,” he replies. “Years ago, these independent studios, I worked at one, came out and they had these onerous milestones and very difficult things, and all these sort of ‘gotchas’ in their contracts. Some of the people were successful there, and they were scooped up by the bigger publishers. Some of them weren't, and they failed and they went away, so there were these years where there was no AAA development happening outside of big publishers. They’re big gambles, right?

“Listen, there's people who invest a lot of money in something, they want to return on that investment. They want to eliminate as many variables as possible to make sure that it's successful, all makes sense to me. But what I saw was this… democratization that's happened between the engines coming out, Unity, Unreal, and then COVID making work from home a lot more accessible and sustainable. I think the combination of that, plus there's been a lot of money in tech, so people can fund these studios and get them started. I can't wait to see what these independent developers make. I think a lot of people like me, we worked for years successfully, and we want to take a shot at making a game that is something of our own.”

Which brings us back to Wyrdsong. Gardiner’s calling it a AAA game, the definition of which can be vague, but when I ask him what he means by it he specifies it as “independent AAA” – an independent studio, setting its own goals, but making “a bigger game with a degree of polish that offers a large, complete feature set that will be a premium product for people to play.” Or, for a shorter definition: “a big, successful RPG.”

Both Gardiner and his co-founder Staples, as well as fellow studio members Paul Haban (Halo: Infinite, Starcraft 2, Heroes of the Storm) and Ekram Rasid (Fallout Shelter, Elder Scrolls: Blades) have plenty of experience and love for that genre, but they’re looking outside of their own past work for inspiration too. In games, Gardiner says Wyrdsong will take cues from the early work of developer Piranha Bytes (the Gothic series), Larian Studios’ Divinity series, Radon Labs’ Drakensang, and Baldur’s Gate. But he’s also looking outside of games, and in some unexpected places.

“I had the opportunity to go to Paris and to the Monet Museum. I realized that Monet makes his paintings similar to how we make games with LOD [level of detail], so the dots are really cool when you're far away from it, up front. I look for inspiration from all sorts of sources, and one of the things in particular for Wyrdsong was Robert Eggers' The Witch. It was a very popular movie, but for me it was more the elements of the unreliable narrator. The fact that you don't know if they're going insane, if you've seen it, if they're going crazy… I love that. I love to explore these sort of mythological histories and the idea that what if what these people experienced was actually real, or at least real to them? That's what reality is, reality is what's real to you, right?

“That's the point of Wyrdsong, just really delve into this. When you look at modern sci-fi and modern fantasy, they've gotten away from a lot of the Tolkien-esque things. Don't get me wrong, I love J.R.R Tolkien and all that, but there's all these questionings of realities in metaverses and multiverses, and how these things all sort of layer in combined. It's all fascinating to me, and to me, video games are the best way to express these topics.”

And of course, per the inspiration for the studio’s name, Gardiner is looking at Shakespeare.

“Shakespeare did this thing where when you expected something bad to happen, something funny would happen, and when you expected something funny to happen, something bad would happen,” he says. “I'm not trying to make a funny game or a terrifying game, I'm trying to make a game that where you don't know what to expect, and in fact, the things you expect are not what's going to happen.”

Though Wyrdsong is still very early in development, Gardiner hopes to have something to show in the coming year: “at least some teases of actual gameplay.” He wants to actively engage the community throughout development, referencing his previous comments about game development being a collaborative effort – that extends to the audience, too. That same audience’s response to the material he and Something Wicked creative will ultimately be the determiner of success for Wyrdsong, not just in sales, but in Gardiner’s mind as well.

“The most rewarding part of having been able to make these games for the last 20 years is when I wear a Fallout shirt at an amusement park, and some kid comes up to me and goes on and on about how the game was not just amazing, but how it actually helped them get through hard times or things,” he says. “So for me, success looks like if this game goes out, and there are people playing it and enjoying it and having those experiences, and just absolutely enamored with it in the way I am when I play other games.”

for this list.

for this list.