RPG Codex Interview: Chris Avellone at Digital Dragons 2016

RPG Codex Interview: Chris Avellone at Digital Dragons 2016

Codex Interview - posted by Infinitron on Sun 5 June 2016, 00:32:19

Tags: Chris Avellone; Fallout 3 (Van Buren); Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic III; Wasteland 2On his second day at the Digital Dragons convention in Cracow last month, Codex representative Jedi Master Radek met up with former Obsidian creative director and current freelancing man of mystery Chris Avellone, who was there to give a talk. He arrived with a big list of questions contributed by our users, and in the resulting 54 minute interview, Chris answered every last one. There's a lot to unpack here, including new information about the unique mechanics in Black Isle's cancelled Fallout 3 (AKA Van Buren) and about Obsidian's unsuccessful pitch for Knights of the Old Republic 3. I'll quote those parts:

However, as interesting as those answers are, I have a feeling they might not be the most commented on part of this interview. You'll understand when you read the full article: RPG Codex Interview: Chris Avellone at Digital Dragons 2016

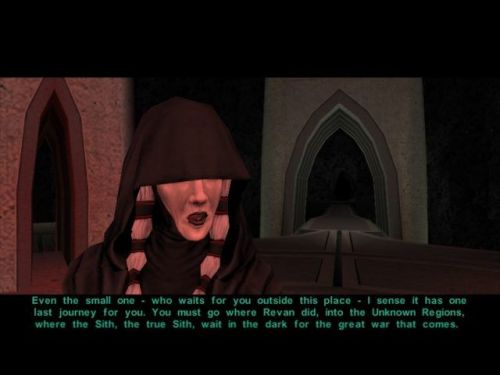

JMR: What was the storyline for the third KotOR game? What would the player do in the Sith Empire? Was it going to be structured like the first two KoTORs: prologue, four planets and then the ending? Or something else?

MCA: So it was gonna be a little bit different. So basically, I think I've said this before, but the player would be following Revan's path into the Unknown Regions, and he goes very, very deep into the Unknown Regions and finds the outskirts of the real Sith Empire. And that's a pretty terrifying place. The intention was that it would be structured on a basic level like KotOR 1 and KotOR 2, but what would happen is you'd have a collection of hubs, but every hub you went to had an additional circuit of hubs, that you could choose which ones you optionally wanted to do to complete that hub, or you could do them all. But ultimately there was just a lot more game area in KotOR 3, just because the Sith Empire was just so fucking big. But yeah, so, on some level it was a similar structure, but it was intended to... so one of our designers, Matt MacLean, had this idea for Alpha Protocol mission structure, where what would happen is, you'd sort of go to a hub, but it wasn't really a hub, it was like a big mission you had to do as an espionage agent, but then there were like six surrounding missions, that central mission, and you didn't have to do any of them, but by doing some of those, you would cause a reaction in the main target mission that could even make your job worse or easier. Or you could choose to try and do all of them, and he let each of them like cater to like, a speech skill, or stealth mission, or shoot 'em up mission, and that would cause different reactivity. And I always liked that, because I felt like you were being given a larger objective, but you were getting a lot more freedom in how to accomplish it and how to set the stage, so it was easier for your character. And that's kind of the mission structure I would have liked to have bring to KotOR 3, because I thought it was much more intelligent design.

JMR: When you worked on Van Buren, what aspect of it did you like the most?

MCA: I liked the idea that the interface was kind of like a mini-dungeon you could explore. The idea when Van Buren was... your Pip-Boy actually didn't start out with all its functionality. Like you had some basic programs, so it acted like a normal interface, but the more you did certain things in the environment, like if you discovered, like, how to set off a fire alarms or you set a fire in a building and the fire alarms went off, suddenly a new functionality of your Pip-Boy, ”Here, let me find all the emergency exits for you!” And then suddenly all of those would be lit up on the map. And you're like, “Oh, wait a minute, I can use this as like a tracking mechanism to figure out where all the exits are.” And you could do that for things like fire suppression system, things like... like where the power sources are in buildings. You could use it to do autopsies on robots and steal their programs, and suddenly your Pip-Boy sort of became like this arsenal that you could use to sort of like navigate the environment. That was cool. And the other thing was... the adversaries in Van Buren could also use your Pip-Boy against you to both cloak their location and track where were you going, so you could actually end up in like a Pip-Boy war, where you're trying to track down each other using a Pip-Boy. So we tried to do a little bit of that in Fallout: New Vegas - Dead Money, where the Botherhood of Steel guy was trying to use the... which basically could have taken over your Pip-Boy, but that was axed, and they were like, “No, you can't do that”, so like, “Oh, shit.”

JMR: Van Buren was supposed to have another party in the world that would wander around and complete quests. Can you tell us how that was supposed to work?

MCA: Yeah, basically what they would do is they would go to alternate locations, and they had their own agenda path they were trying to follow to accomplish certain objectives. And the trick with them is each one of the rival party members actually had a separate agenda, which they didn't fully share with everybody else in the party. So sometimes they would do certain things at locations where it worked with one of their agendas but nobody else's, but the other guys wouldn't know about it, so you could use that against them, where you're like, ”Well you know that guy in that location left a note for us to follow you”, and they're like, “Oh my god! Are you a traitor?” [shooting sounds] But... it was basically a very heavily scripted NPC mechanic, where we were like, we're trying to increase reactivity and the sense the world was moving on. So, when the player characters would go to one location and do a bunch of stuff, they would be notified that something else was happening in the location and those guys would take care of the quests in an area or conquer that location, and you were like, “Oh, shit”, like, “We gotta move.” But it was all intended to give the sense that something else was happening in the world without waiting for you.

MCA: So it was gonna be a little bit different. So basically, I think I've said this before, but the player would be following Revan's path into the Unknown Regions, and he goes very, very deep into the Unknown Regions and finds the outskirts of the real Sith Empire. And that's a pretty terrifying place. The intention was that it would be structured on a basic level like KotOR 1 and KotOR 2, but what would happen is you'd have a collection of hubs, but every hub you went to had an additional circuit of hubs, that you could choose which ones you optionally wanted to do to complete that hub, or you could do them all. But ultimately there was just a lot more game area in KotOR 3, just because the Sith Empire was just so fucking big. But yeah, so, on some level it was a similar structure, but it was intended to... so one of our designers, Matt MacLean, had this idea for Alpha Protocol mission structure, where what would happen is, you'd sort of go to a hub, but it wasn't really a hub, it was like a big mission you had to do as an espionage agent, but then there were like six surrounding missions, that central mission, and you didn't have to do any of them, but by doing some of those, you would cause a reaction in the main target mission that could even make your job worse or easier. Or you could choose to try and do all of them, and he let each of them like cater to like, a speech skill, or stealth mission, or shoot 'em up mission, and that would cause different reactivity. And I always liked that, because I felt like you were being given a larger objective, but you were getting a lot more freedom in how to accomplish it and how to set the stage, so it was easier for your character. And that's kind of the mission structure I would have liked to have bring to KotOR 3, because I thought it was much more intelligent design.

JMR: When you worked on Van Buren, what aspect of it did you like the most?

MCA: I liked the idea that the interface was kind of like a mini-dungeon you could explore. The idea when Van Buren was... your Pip-Boy actually didn't start out with all its functionality. Like you had some basic programs, so it acted like a normal interface, but the more you did certain things in the environment, like if you discovered, like, how to set off a fire alarms or you set a fire in a building and the fire alarms went off, suddenly a new functionality of your Pip-Boy, ”Here, let me find all the emergency exits for you!” And then suddenly all of those would be lit up on the map. And you're like, “Oh, wait a minute, I can use this as like a tracking mechanism to figure out where all the exits are.” And you could do that for things like fire suppression system, things like... like where the power sources are in buildings. You could use it to do autopsies on robots and steal their programs, and suddenly your Pip-Boy sort of became like this arsenal that you could use to sort of like navigate the environment. That was cool. And the other thing was... the adversaries in Van Buren could also use your Pip-Boy against you to both cloak their location and track where were you going, so you could actually end up in like a Pip-Boy war, where you're trying to track down each other using a Pip-Boy. So we tried to do a little bit of that in Fallout: New Vegas - Dead Money, where the Botherhood of Steel guy was trying to use the... which basically could have taken over your Pip-Boy, but that was axed, and they were like, “No, you can't do that”, so like, “Oh, shit.”

JMR: Van Buren was supposed to have another party in the world that would wander around and complete quests. Can you tell us how that was supposed to work?

MCA: Yeah, basically what they would do is they would go to alternate locations, and they had their own agenda path they were trying to follow to accomplish certain objectives. And the trick with them is each one of the rival party members actually had a separate agenda, which they didn't fully share with everybody else in the party. So sometimes they would do certain things at locations where it worked with one of their agendas but nobody else's, but the other guys wouldn't know about it, so you could use that against them, where you're like, ”Well you know that guy in that location left a note for us to follow you”, and they're like, “Oh my god! Are you a traitor?” [shooting sounds] But... it was basically a very heavily scripted NPC mechanic, where we were like, we're trying to increase reactivity and the sense the world was moving on. So, when the player characters would go to one location and do a bunch of stuff, they would be notified that something else was happening in the location and those guys would take care of the quests in an area or conquer that location, and you were like, “Oh, shit”, like, “We gotta move.” But it was all intended to give the sense that something else was happening in the world without waiting for you.

However, as interesting as those answers are, I have a feeling they might not be the most commented on part of this interview. You'll understand when you read the full article: RPG Codex Interview: Chris Avellone at Digital Dragons 2016

[Interview by Jedi Master Radek]

Jedi Master Radek: A few years ago, you said you had an idea for a Star Wars RPG set during the Empire era. Could you tell us more about it?

Chris Avellone: Yeah... so that game was set during the dark times of the Republic when everything was falling apart, but there were still a few scattered Jedi lying around. The premise was that you'd be one of those Sith and you'd go around hunting down and killing Jedi. However, then I read the Dark Horse comic series called “Dark Times” that was written by Randy Stradley and that story was far better than any story I could have come up with. [laughs] So yeah, that was the premise, basically. You'd be one of the Imperial agents and/or Darth Vader, and then you would just go around hunting down and killing all the Jedi.

JMR: You said on Twitter you were involved in the preproduction of Tyranny. How much of it will be shown in the final game? Was this involvement only on the design documents level or will we get some of your writing in the actual game?

MCA: There is none of my writing in Tyranny. And the preproduction period was all I was involved with, so I actually don't know how much of that stuff will actually show up in the final game.

JMR: How much, if any, of your actual writing is in Wasteland 2? Nathan Long said you left after finishing design documents for your locations.

MCA: I didn't do any dialogue writing for characters. I did the revisions and contributed to the story document, the vision document and a lot of work on the area design documents which weren't the final areas that got implemented. But that was the work that I did on Wasteland 2, yeah.

JMR: The environmental descriptions in the Ag Center, were they your work or Nathan's?

MCA: I remember doing a few samples lines for that, but I don't think the final ones made it in.

JMR: How is it like working with Larian? How is it different from working with Obsidian or inXile?

MCA: The story process on Larian is as collaborative as inXile and more collaborative than Obsidian. There's a lot more writers involved in the storyline for Larian, about the same level for inXile, and what we do is we all get on to Skype and Google Documents and then we sort of have like a remote meeting, where we talk through each of the plot points one by one and try and make sure that it's compelling, it's interesting, and we just keep doing that until the story feels right. We've moved on from the story and now we're doing the player character origin story, which is kind of like the background you can choose for your character, and that's currently what I'm involved with right now. I got to write the Undead origin story, which is pretty cool.

JMR: You said some of your inspirations for Torment came from Japanese RPGs.

MCA: [laughs]

JMR: How much are you interested in Japanese culture? Do you have favorite Japanese movies or anime?

MCA: I do have a few animes that I like, I like Samurai Champloo. I also liked Cowboy Bebop. I really liked a series called Trigun. I like Attack on Titan, even through I didn't like it at first. But mostly the influence from Japanese RPGs came from how they did their companion design. What I always liked about JRPGs is I felt like they always gave you enough time to get to know the companion character and try them out before moving on to the next guy. Because some of the trap that Western RPGs fall into is they'll introduce a few characters at the beginning that you get really attached to, but then when you meet a new character you don't want to switch out because you're comfortable with the old guy. Japanese RPGs stage it so everybody gets equal screen time at the beginning, and it's staggered out. And then at the end, they let you choose, but you've been introduced to all the characters sort of at once, in stages, and I think that works a lot better.

JMR: What part of your work that was cut was the most difficult to let go of?

MCA: None of it. Part of a narrative designer's job is that you don't really get attached to anything and you're supposed to make sure that the content fits with the direction for the title. The most difficult part was how it was handled. I got to hear second-hand that it was gonna be cut and later on the creative lead apologized to me about it. But that didn't really change how the process worked. And what I... I mean, the changes happened and I was happy to make the changes but I thought the entire thing was held extremely poorly.

JMR: It was me who found out about the Van Buren trademark.

MCA: [laughs] Eh, good for you! Good job! What's up, detective?

JMR: Could you please tell us how work on the project is going?

MCA: [smiling mischievously] Oh, I couldn't say something like that! No, that would be saying too much! [laughs]

JMR: Don't you owe the Codex some troll drawings?

MCA: So I had a question about that. I actually don't know what drawings those are. I thought I'd already given them, all the troll drawings. So I drew one on Twitter and sent it to them right before this interview. So that's one less drawing, but if they have a list of stuff that I haven't delivered, please let me know.

JMR: Fans really want an RPG with MCA as lead writer again. Will that ever happen? Even if it means working for Larian, inXile or any other company that shows interest? Many of us think that when you only write a character or two, or assume a strictly supervisory role, then that waters down the Avellone experience.

MCA: So I absolutely would be a lead writer again. It depends on the company. I did not want to be a lead writer at Obsidian. I would be a lead writer at another company. The issue with Larian is they already have a story structure in place. And the same thing with inXile. But under the right circumstances I absolutely would do it again.

JMR: Great! I can't wait, I've been waiting ten years for this!

MCA: [smiling] Yeah.

JMR: What would a company need to offer you to join them? Full creative control over your projects? Something else?

MCA: [thinks for a while] So... a number of companies have offered me a great deal to do my own project. The issue is that I really can't do it right now. And the problems are... there's a lot of stuff going on with family and also I can't work anywhere full-time until all that stuff is resolved. So that's kind of a challenge.

JMR: You said during the conference that you're working on an unannounced project to be announced later this year. Is it an RPG?

MCA: Oh... I can't even say anything about it beyond that it's coming. [laughs] I think if I gave any details that actually would be too much, but shouldn't be too much longer. [laughs]

JMR: Aw... I was actually going to ask if it's a new IP or not, or are you working with a company you worked with previously or not, but you won't answer I guess...

MCA: Yeah. Unfortunately I couldn't say anything. I'd love to, I'm happy to talk about it after it's announced but...

JMR: What work of fiction you have experienced in recent months has inspired you the most, and in what way?

MCA: [thinks for quite a while] That is a good question. Um... [thinks for a while] So... what have I read recently? That actually... well, there's a few things. Oddly enough, I've been reading The Great Gatsby. [laughs] And what I really like is the metaphor usage in the book. So much so that I think about how that could be used as weapons. [laughs] The other thing is... I've been reading Brandon Sanderson's Steelheart series and I'm kind of a sucker for superheroes and supervillains. And even though I didn't like the first book, I did like the second book much more. And I'm enjoying the third book right now, mostly because the ideas they have for the supervillain powers are really interesting to read. And it's kind of fun to try and figure out what each villain's weakness is. And... so I'm enjoying that a lot.

JMR: What do you think of the approach of games like Dark Souls or Divinity: Original Sin to storytelling, where the player has to discover the plot rather than the plot shoving itself down the throat of the player? What are the advantages and disadvantages of this non-linear approach?

MCA: [surprised] Oh, okay. Yes, so... all right, so Dark Souls is one of the games that I use in the example of how visuals and very minimal prose can communicate a lot about a world, without someone talking at you. And what I really like about Dark Souls, I think, visual storytelling, they do a great job, but then with their inventory items, those also tell a story with very minimal attacks. So those are two things that I wish more narrative designers would pay attention to.

JMR: Are you good at playing Dark Souls? [couldn't resist]

MCA: Are you kidding? I'm not good at playing any games. I suck at everything! [laughs]

JMR: Well, there are no wolves in Dark Souls! [I meant wolf trash mobs. Sending MCA against Sif would be an act of cruelty]

MCA: [laughs] Yeah. Every game I play I get my ass kicked, but I still enjoy it. [laughs]

JMR: What's your dream project? Do you think you'll ever realize it? On the same note, hypothetically, if you didn't have to worry about financial returns, what game would you make?

MCA: So I don't care about financial returns anymore, because that doesn't make me happy. If I were to work on a dream project, I probably couldn't say too much about it, but it would probably have to wait for a little while until family stuff settles down, but um... it would probably not involve a lot of text. [laughs] It would probably be a story more conveyed through visuals.

JMR: How often does your feedback actually influence the final outcome of a game?

MCA: Do you mean feedback from players, or feedback from the player who'll play in the game?

JMR: No, I mean the feedback you give to other companies.

MCA: Um... [thinks for quite a while] Well, so, on Wasteland 2... we did have a story motivation meeting that... got a little debate-heavy because... no one could figure out a motivation for the Synths. Like no one... they're like, “Okay, well, we're not really sure why these guys are invading the wasteland” and I... so, during that meeting in about ten minutes I was able to break down what their motivation should be, and it was pretty simple because it was already the part of the gameplay loop. Like basically, the Synths' motivations was trying to basically convert as many humans and communities as possible to their way of thinking for spare parts. Like, that's pretty simple, but I think it just took a lot of back-and-forth discussions before that came about, and I actually don't know if that ended up being the final motivation in the game, but it certainly seemed to solve a lot of questions during that meeting. When I came to Numenera, um... [thinks for a while] I don't think that anything related to the story direction, they necessarily used for the end part of the game. The only thing that I asked to be done was just to make sure that each of the Tides you do in the game... that you feel that your interactions with those Tides was significant for the end encounter, but I think they had that covered anyway.

JMR: You actually designied the last part of Wasteland 2, the Synth base, yes? [I was trying to get information about the cut content at Seal Beach]

MCA: No... I worked on an area called the Refinery that I think got cut and then there was also um, another community, I think, near the end base but that also got downscaled at the end of the game. Most of my contributions were Highpool, Agricultural Center, and then one of the secret shrine locations, I think, was the only areas that survived.

JMR: Are there themes you do not include in your writing for fear of pissing people off?

MCA: Not people... not players. Publishers, for sure. There are certain franchises, where there are certain subjects they don't want you to talk about. And any other times I've attempted to include material that I think would be hotly debated, that's been cut.

JMR: What is more difficult for you? Creating concepts, like who is this guy, what are his motivations, his personality? Or doing the actual writing, bringing individuals to life with words?

MCA: So, doing the actual dialogue, writing, that's always the hardest. And I usually find that trying to do a concept for a character that you haven't written a word of dialogue for is sometimes a waste of time. Because once you start writing, that person becomes totally different. Like, once you start channeling the words, you don't always closely follow the concept anymore, you sort of let the character kind of pull you along where they want to go. So sometimes it ends up being different than the concept.

JMR: Which of your famous characters have ended up going in a different direction?

MCA: Um... Ulysses did. Kreia didn't. Um... the Disciple in KotOR 2 did. He turned into kind of a big pussy, but that for some reason, that's how he came out. Uh... the character Sand in Neverwinter Nights 2 was never supposed to be written that way. But then he just came out that way. Also, Grobnar in Neverwinter Nights 2 came out a lot differently and then the voice acting made him worse. Um... those are a few examples.

JMR: Creating stories you always have some ideas and motives in mind. How often does the audience misread them? Have you found any surprising interpretations of your work?

MCA: Oh yeah! So the first problem that usually occurs is someone assumes that I'm trying to push some real world political agenda or some real world religious philosophy into a character, and I never am. All I'm doing is I try and examine the world that character lives in, and then I give him a perspective. But people always seem to want to take it to a real word philosophy or religion or political agenda kind of place, when that's not the case at all. [laughs]

JMR: Well, that's what people do!

MCA: [laughs] Yeah they do, that's what they do. But then I feel bad because they make a very intelligent interpretation of what I did, and then I'm embarrassed because mine isn't very intelligent. [laughs] So that's kind of embarrassing. [laughs]

JMR: When you're not the lead designer on a game, the parts of it you're working on have to fit with somebody else's vision. What challenges does this pose? Have you ever found yourself complying with a vision you didn't like?

MCA: Do you mean, did I ever uphold like, a design direction I didn't agree with?

JMR: No, I mean motifs, themes, general concepts.

MCA: Um... [thinks for a while] That's a good question. Um... [thinks for a while] Well, I guess in Pillars of Eternity I didn't always quite understand the spirit recycling mechanic. Um... I didn't always understand how that worked with the spell system and other elements of the world. And I think the way I interpreted people living forever was a little bit different than everybody else. And also I got a little bit confused about um... well, I got confused about the fact that the central premise in Pillars is an interesting one, but I don't know if the story, including the stuff that I wrote, helps support that theme. Because in order for that theme to work, you need to emphasize how important the gods are in that world, and I never really got the sense they were really all that important.

JMR: What concept would you most like to explore in a future project? What concept do you think is overused in RPGs?

MCA: The idea of a chosen one. “Oh, I'm special”, especially when there's no real reason behind it, and... that's a problem. Another motif is, for some reasons you're the only one doing things. The rest of the world holds still while you take your time, I think that's kind of garbage. Also... [thinks for a while] This is kind of weird, but what I don't like is I feel there's a lot of games that introduce very interesting characters right from the outset, like in New Vegas, like you get Sunny Smiles and her dog. I would have liked to have her as a companion, but for some reason those characters never seem to be able to join your party which is kind of weird, and then they're kind of shuttled off and forgotten, which just is kind of bizarre. So I don't really understand why that happens, when in fact that's one of the best opportunities to introduce a companion character. And if it's up to me I try to make sure you can, but when games don't do that, that feels weird.

JMR: [flips through pages searching for the next question]

MCA: Oh, I'm sorry, also like one other thing... like, sometimes I think, uh... some writers fall into the trap that they have to explain everything to the player. Like they just give like a huge word vomit dump about like what everyone's thinking and what my grand plan is. And you know what, players aren't dumb. Like, you can seed that stuff around and players can make the logical leaps about what people's motivations are, why they want to do things, without them having to come out and say it. And sometimes when you get faced with exposition like that... I just shake my head and want to cry. Because it would have been far more interesting if you could help interpret what their motivations were and see how they came to be, rather than them just telling you how things happened. And that's kind of irritating.

JMR: When you talked... oh sorry, this is about Van Buren so I won't ask.

MCA: [laughs] I... you know, if such a project exists I would be happy to talk about it. But I can't talk about it. But good detective work, well done!

JMR: I guess you won't say anything about Autoduel either.

MCA: [laughs] Yeah. Also... no, I'm sorry, go on.

JMR: No no, say what you wanted to say!

MCA: Oh no no, I'm sorry.

JMR: You come across as a very humble guy, always good-willed towards others. Were you always like that, or is it something you learned during your life?

MCA: Uh... well, that's a kind way of interpreting it. I guess the way I would interpret it is... it's always worthwhile to be pleasant and share respect to everybody, until the moment that you realize that they don't treat you the same way. And when you suddenly realize that some people are poison, those are the people... you're not mean to them, but you just cut them out of your life. You're like, “You know what? Having you in my circle or around me or knowing anything about me has proven to be poisonous in our relationship, and I can't have you in my life anymore.” But I try and be quiet about that, but I feel everybody else deserves a fair shot and I... I wasn't the most outgoing person in the world, and I always appreciated people that were nice to me and went out of their way to make me feel welcome and invited. But with the game community everybody's like that. We all like games, we all like the same interests. It's really easy to have a conversation. I rarely meet a mean game developer or a mean game player. Like everyone's just so nice, it's not hard to be nice to people who are nice in the first place.

JMR: You said on Twitter that you were going to work with the Fallout IP at the source. What did you mean?

MCA: Fallout IP at the...?

JMR: At the source.

MCA: No no no, I wasn't going to work on it. I would prefer to work at the source, and the reason for that is because they're in control of the lore. The problem is if you're... if you're one step removed from any franchise, whether it's Star Wars or Fallout or whatever, if you're not there, at the place that owns the actual lore, there is a lot of hoops you have to jump through to get stuff approved, and it's exhausting. So if I were to work on Fallout, what I want to do is actually work at the place where the lore is being developed. Not have it passed off to me for approvals and back and forth because... I don't think that's very efficient.

JMR: In a cut ending for Torment, there's a movie showing the Nameless One waking up in the mortuary without his memories. What player actions were meant to lead to this outcome?

MCA: [thinks for a while] Wait, there's a cut movie that shows that?

JMR: I don't know if it was a movie or if it was a planned ending...

MCA: That may have been an ending planned early on, I actually don't remember. But I do know that it was almost so impossible to get resources to do a movie. We did not have the freedom to do a lot of those. So we were actually lucky to get the movies that we did. And... Torment was a pretty small team, especially compared to Baldur's Gate [laughs]. So it's possible that was planned... but I don't remember that clearly, and also I'm guessing we probably just would never have the resources to do it anyway. So I'm not surprised if that would have been cut probably halfway through development. But it's certainly a viable ending. It would make sense to me.

JMR: Do you have any other unannounced projects besides the ones we spoke about before? Let's say, how many unannounced things are you working on now?

MCA: [thinks for a while] Quite a few. [laughs] And that's all I can say.

JMR: More than three?

MCA: Quite a few. [laughs]

JMR: Did you do any work on Dwarfs?

MCA: No... so, my work on Dwarfs was... I reviewed the work that Kevin Saunders and Brian Mitsoda did. Because Brian Mitsoda was the lead story writer for Dwarfs. And I think he did a really good job of sort of categorizing what each dwarf's personality was, what their character arc and abilities were. And Kevin did a good job of managing the project. My involvement was mostly on an advisory capacity, where I'm like “Okay here's my thoughts on the story, like, here's elements that I like, here's things that I think are working really well, here are things I think need to be shored up a little bit.” That was basically my involvement on Dwarfs.

JMR: Were the dwarfs party members?

MCA: Yes.

JMR: All of them?

MCA: Yeah, but you could only switch out two at a time, so like, you have a main character and then you'd be able to choose two dwarfs to join you in a party. And each of them had special powers and abilities, and you'd just switch them out.

JMR: Who was the villain?

MCA: [thinks for a while] Not sure I can say. Um... the dwarfs I'm gonna talk about but the villain I will leave for another time. [laughs] It was a really weird franchise, though. The fact that someone wanted to do Snow White and the Seven Dwarves as an RPG... I was like, “All right, that's weird.” [laughs] But then, they wanted to do it... a thousand years before Snow White. So you saw like, all the history that led up to the Snow White world, and that was really cool. And then I like got it, I'm like, ”Oh, okay, I understand why it's cool now”, so... but initially I didn't think it was very cool.

JMR: Was it a light-hearted or dark RPG?

MCA: Kind of around the middle.

JMR: There were talks ten years ago with White Wolf about Obsidian making a World of Darkness game in the Neverwinter Nights 2 engine. Do you have any idea what story you would have told in this game?

MCA: No... um, I don't even, I... gosh... so I wouldn't have done that. I don't recall it... I don't think it lends itself well to an isometric game, per se. I guess I'd have to see more elements of the design, but I don't know if I would have done a Neverwinter World of Darkness, but this is outside of... like, this is just my thoughts. Like, I don't recall anything like that nor would I have supported something like that.

JMR: You worked for some time on Hidden. Could you tell us something more about it?

MCA: What was this?

JMR: Hidden.

MCA: [thinks for a while, looks puzzled] Oh... wow, you're really good. No, I can't say anything about that. Unfortunately. [thinks for a while] Wow, you're good.

JMR: Actually, I got it yesterday from Feargus.

MCA: Oh, and what did Feargus say about it? Because then I can go off of what Feargus said.

JMR: [I related what I remembered of Feargus' description to Chris]

MCA: [thinks for a while] Oh, yeah... wow... yeah, that didn't happen. [looks at some distant point on the horizon] God... I can't say anything more, it'd just go bad.

JMR: What was the storyline for the third KotOR game? What would the player do in the Sith Empire? Was it going to be structured like the first two KoTORs: prologue, four planets and then the ending? Or something else?

MCA: So it was gonna be a little bit different. So basically, I think I've said this before, but the player would be following Revan's path into the Unknown Regions, and he goes very, very deep into the Unknown Regions and finds the outskirts of the real Sith Empire. And that's a pretty terrifying place. The intention was that it would be structured on a basic level like KotOR 1 and KotOR 2, but what would happen is you'd have a collection of hubs, but every hub you went to had an additional circuit of hubs, that you could choose which ones you optionally wanted to do to complete that hub, or you could do them all. But ultimately there was just a lot more game area in KotOR 3, just because the Sith Empire was just so fucking big. But yeah, so, on some level it was a similar structure, but it was intended to... so one of our designers, Matt MacLean, had this idea for Alpha Protocol mission structure, where what would happen is, you'd sort of go to a hub, but it wasn't really a hub, it was like a big mission you had to do as an espionage agent, but then there were like six surrounding missions, that central mission, and you didn't have to do any of them, but by doing some of those, you would cause a reaction in the main target mission that could even make your job worse or easier. Or you could choose to try and do all of them, and he let each of them like cater to like, a speech skill, or stealth mission, or shoot 'em up mission, and that would cause different reactivity. And I always liked that, because I felt like you were being given a larger objective, but you were getting a lot more freedom in how to accomplish it and how to set the stage, so it was easier for your character. And that's kind of the mission structure I would have liked to have bring to KotOR 3, because I thought it was much more intelligent design.

JMT: Sounds really cool.

MCA: Yeah, it was a great idea he had. He was very modest about it. I think he still gets mad when I bring it up. [laughs]

JMR: What functionalities and gameplay elements do you want to see in future RPGs?

MCA: Oh, less talking. More things that you see. More stuff that you do to interact with the environment. Like, one thing I like about Divinity is, they have in my opinion superior dungeon exploration mechanics. I think the way that you can manipulate the environment very easily to solve sort of environmental puzzles, I think it's really cool. And it makes me wish that other games would do, would follow their footsteps. But I'd like to see more ways for the player engaging with the dungeon environment that isn't just talking to NPCs and killing monsters.

JMR: How do you view your career? Is there something you regret not having done?

MCA: [thinks for quite a while] Um... no. I feel like... if not then... I now get to work on everything that I want to work on. Like, it started with Wasteland 2, I'm like, “I already worked on Wasteland.” I had to work on Fallout. Now there's a whole selection of people and companies that I can work with freely and there's no obstacles to it. So... I don't regret anything. I think if I had only one regret, it's that I didn't go out into the game world earlier. I was worried that... a game company was my only life, and there wasn't anything outside that. And that's my only regret.

JMR: What do you think of the pragmatic approach to game design versus creative approach to game design?

MCA: Do you mean in terms of like approaching it from like, resources and budget and things like that, or do you mean... is that what you mean by pragmatic?

JMR: Yes, actually, yes.

MCA: Well, I guess I've never been in a position where I have unlimited funds and unlimited time, and I also think being in that position is very dangerous, because really bad games and bad media get made that way. Mostly because people don't feel any pressure whatsoever to wrap things up and finish things. So I'll be honest, like, I usually try and do a blend of both, because I've been so trained that there's never enough time to do everything that you want. So you need to start locking stuff down early and making realistic decisions as early as possible, because the game will be better for it.

JMR: In the game industry you need to make compromises - compromises on difficulty, scope, mechanics, innovation and accessibility - to actually deliver a successful product. But at what point do those compromises become too much? Is there a point where a game can completely lose any creativity and artistic merit because of those compromises?

MCA: The only compromises that immediately jump to mind as being the worst is when QA is compromised. And the willingness to fix whatever QA finds as compromise, that's the first problem. Because at that point it's pretty clear that noone really cares about the end product, they just want it out. And that's a little thing I call “quality when convenient”, and the problem is there's a certain period in about every project where everybody's like, “Oh, quality! We're gonna make this the best thing ever. It's gonna be like so innovative, it's gonna be great!” And then the moment there's any hardship, everyone gives up. And they're like, “Oh god! Get it out the door. I don't care how many bugs there are.” And if you've worked for two years on a project and people around you started taking that attitude, that's death. Like, you're just like, “Why did we work so hard and put so much love in this game if you just don't care about it and you're not willing to sacrifice for it?” Because every sacrifice you make like that, you may think you're doing the right thing, you're like, “Oh well, in terms of budget this makes sense to cut it like this.” But then you like, you don't consider... like, people don't consider reputation, they don't consider what that says to your public, they don't consider what it says to the players and sometimes to make a really good game, like, you have to sacrifice. It sucks, like, you go into death. Like, you spend more money than you wanted to, but in the end I feel it's worth it, because every time you deliver a quality product, like where it's polished and... not everyone has to love it, but you made a quality game. People respect you reputation-wise for that. And every time you compromise that just weakens your reputation, bit by bit, until noone trusts you anymore. And that's just a sad way to be. Um... okay, but in terms of creative compromise... so, I feel like we had a bit of this on... on Wasteland 2, but when I say that I mean there were people that didn't want certain features in the game. And sometimes that made sense and at other times I felt like they were always willing to listen to our reasons for why we weren't gonna include it. And the fact that they knew that we were listening to them and we had a really good, well-thought out answer for why that was gonna be the case, I think that helped our argument. Because like, “You know what? Okay, I don't a hundred percent agree with it, but they did take the time to personally explain it to me, they included all the details for the reasoning as to why they did it.” And then sometimes those people become our best advocates, because then they take those ideas and when somebody else has the same question, they're able to speak about it. So that works out pretty well. It doesn't work in every single situation, but that's been my experience.

JMR: What's your favorite Obsidian game, and why?

MCA: [thinks for quite a while] I don't think I have one. I think my favorite game is probably... is just the ones back at Black Isle. Like, I mean, I... even though it didn't see the light of day I really loved working on Van Buren. I really liked working on Fallout 3, I liked the pen-and-paper game for Fallout 3. But there... most of the games that I liked were back at Black Isle.

JMR: When you worked on Van Buren, what aspect of it did you like the most?

MCA: I liked the idea that the interface was kind of like a mini-dungeon you could explore. The idea when Van Buren was... your Pip-Boy actually didn't start out with all its functionality. Like you had some basic programs, so it acted like a normal interface, but the more you did certain things in the environment, like if you discovered, like, how to set off a fire alarms or you set a fire in a building and the fire alarms went off, suddenly a new functionality of your Pip-Boy, ”Here, let me find all the emergency exits for you!” And then suddenly all of those would be lit up on the map. And you're like, “Oh, wait a minute, I can use this as like a tracking mechanism to figure out where all the exits are.” And you could do that for things like fire suppression system, things like... like where the power sources are in buildings. You could use it to do autopsies on robots and steal their programs, and suddenly your Pip-Boy sort of became like this arsenal that you could use to sort of like navigate the environment. That was cool. And the other thing was... the adversaries in Van Buren could also use your Pip-Boy against you to both cloak their location and track where were you going, so you could actually end up in like a Pip-Boy war, where you're trying to track down each other using a Pip-Boy. So we tried to do a little bit of that in Fallout: New Vegas - Dead Money, where the Botherhood of Steel guy was trying to use the... which basically could have taken over your Pip-Boy, but that was axed, and they were like, “No, you can't do that”, so like, “Oh, shit.”

JMR: That sounded really ambitious.

MCA: Oh, it actually wasn't too hard, actually most of it just involved rewriting quest text and some of the interface prompts, and that was pretty much about it. But I think they just thought it was too weird.

JMR: Van Buren was supposed to have another party in the world that would wander around and complete quests. Can you tell us how that was supposed to work?

MCA: Yeah, basically what they would do is they would go to alternate locations, and they had their own agenda path they were trying to follow to accomplish certain objectives. And the trick with them is each one of the rival party members actually had a separate agenda, which they didn't fully share with everybody else in the party. So sometimes they would do certain things at locations where it worked with one of their agendas but nobody else's, but the other guys wouldn't know about it, so you could use that against them, where you're like, ”Well you know that guy in that location left a note for us to follow you”, and they're like, “Oh my god! Are you a traitor?” [shooting sounds] But... it was basically a very heavily scripted NPC mechanic, where we were like, we're trying to increase reactivity and the sense the world was moving on. So, when the player characters would go to one location and do a bunch of stuff, they would be notified that something else was happening in the location and those guys would take care of the quests in an area or conquer that location, and you were like, “Oh, shit”, like, “We gotta move.” But it was all intended to give the sense that something else was happening in the world without waiting for you.

JMR: Was it one party or more?

MCA: One.

JMR: Their activity... was it scripted to occur at certain times, or triggered by player actions?

MCA: Sometimes it was time, and sometimes it was events. Sometimes if the player characters did something specific, the other party would have to react to it. And then other times it was time-based, just like in Fallout. I don't know how well would it have worked, but I wanted to try it. [laughs]

JMR: It's a great concept. Would you try it again in a future game?

MCA: Sure.

JMR: What are the strong points of your writing? Why isn't gaming isn't recognized as a storytelling medium like movies or books? What is lacking in video game storytelling?

MCA: I think a lot of computer games stories don't focus on the player enough. I think some writer gets it into their head that they want to tell a story about the world that isn't really involved with the player. The player just gets injected to it. I think that's the biggest problem. Ideally a computer game story very selfishly focuses on the player, and pays attention to the stuff that he does and reacts very specifically to that character, rather than trying to tell a completely separate story, where the player just happened to be along and happened to influence, but it isn't really about him at all.

JMR: Do you prefer playing predefined characters like The Nameless One from Torment or blank slate characters like the Bhaalspawn from Baldur's Gate?

MCA: Um... [thinks for a while] No, I don't really think I have a preference, I think... no, I don't think I do.

JMR: In the wake of the RPG Renaissance, there have been many new games coming out like Dragonfall, Age of Decadence, Underrail, Serpent in the Staglands, Telepath Tactics and many more. Which of these less-known games have you played, and which are you definitely going to play? Have you been inspired by one?

MCA: So... I don't have a lot of time to play roleplaying games, unfortunately. Most of the games that I play I'm either testing builds of games that I'm working on and trying to find all the bugs and the story pacing problems. So that consumes a lot of my time. And then, when I get done with that, if I'm lucky I have fifteen to twenty minutes to play Darkest Dungeon before I go to bed. And Darkest Dungeon is not a very relaxing game. [laughs] But the titles that you quoted I haven't had a chance to try any of them yet. I did like the look and feel of Serpent in the Staglands, it gave me that old Ultima vibe. And I've heard really good things about Age of Decadence. I think that the creators sent me the demo to play a long time ago, but I... I think I played about an hour of that and gave them some feedback on it. But I didn't dive very deeply into Age of Decadence unfortunately, but I've heard nothing but good things about it.

JMR: Since we're talking about Serpent in the Staglands, you know the creators are running a new Kickstarter, Copper Dreams?

MCA: Oh, really? Oh fucking yay!

JMR: [frantically trying to explain the game]

MCA: So it's the same company? Okay, cool. Wow!

JMR: All the new cRPG offerings coming out these days have brought the genre back to life. People talk about them, people play them, and they're mentioned in the press quite often. How many young players are falling in love with the genre? Have you done any market research? Is the new generation of cRPG players large enough to sustain it?

MCA: Um, yeah... actually, so I don't have any market research, but there's two patterns that I've noticed. One is, there's a whole new group of players that enjoy the BioWare RPG, when it comes to character relationships, that never used to exist before. I think that's a good thing. The other thing that I've seen is, I think the Bethesda RPGs have gone so mainstream that a lot of people who normally wouldn't play an RPG will play a Bethesda RPG, which I think is a good thing for them. Anyway so, my feeling is the generation is growing, but they don't play all the RPGs in the genre, just certain specific ones.

JMR: Do you think that it's common to start out as a BioWare or Bethesda player and then move on to something more... let's say, heavy?

MCA: Well, I think it just depends on what your playstyle is. Um... [thinks for a while] I don't have a good answer for that. I think that people should just play things that, you know, they gravitate towards. I usually find, for example, like board game players tend to enjoy the more hardcore RPGs, a lot of stats and min-maxing and stuff like that. And then there's other players that play more casually and they just want to be... the middle of a good story and a good heroic epic, and they don't really care so much about what they're butchering or who they're shooting. They just want to get to the story and enjoy it.

JMR: Do you think pop culture has become too conservative, playing it too safe with its products? For example, Hollywood seems to be relying entirely on franchises and remakes these days. Even movies which are not remakes, like the new Star Wars movie, can turn out to be remakes in disguise.

MCA : Yes. So the answer is yes, and the reason for that is financial. It's because... my feeling is that they're worried they're not going to make as much money if they try and do something different. And because there's so much money being invested in large computer games and movies, that's what causes people to not want to veer away from what they think people will like. But I don't think that they're always right about what people like. They just are trying to play it safe. And that's kind of why I like a lot more of the indie projects, indie RPGs. I feel like they have more room to experiment and that's what makes them interesting.

JMR: Well, my list of questions is over.

MCA: Oh my god! Ta-tada! [laughs]

JMR: Maybe just one more question. Can you tell us something we don't know about the Alien RPG you were making?

MCA: Oh... [thinks for a while] I don't know, I might ask Obsidian about that, because I don't think there's anything more that I can say about it that I haven't already said. I'm just sorry it wasn't done. [laughs] That's what really sucked. I mean, we were really enjoying working on it, and the character concepts were really cool, and just... I have no idea why it didn't happen. So that's... I don't really know too much, so there's actually not a lot I could say. I'm sorry, I wish I had a more interesting answer. [laughs]

Jedi Master Radek: A few years ago, you said you had an idea for a Star Wars RPG set during the Empire era. Could you tell us more about it?

Chris Avellone: Yeah... so that game was set during the dark times of the Republic when everything was falling apart, but there were still a few scattered Jedi lying around. The premise was that you'd be one of those Sith and you'd go around hunting down and killing Jedi. However, then I read the Dark Horse comic series called “Dark Times” that was written by Randy Stradley and that story was far better than any story I could have come up with. [laughs] So yeah, that was the premise, basically. You'd be one of the Imperial agents and/or Darth Vader, and then you would just go around hunting down and killing all the Jedi.

JMR: You said on Twitter you were involved in the preproduction of Tyranny. How much of it will be shown in the final game? Was this involvement only on the design documents level or will we get some of your writing in the actual game?

MCA: There is none of my writing in Tyranny. And the preproduction period was all I was involved with, so I actually don't know how much of that stuff will actually show up in the final game.

JMR: How much, if any, of your actual writing is in Wasteland 2? Nathan Long said you left after finishing design documents for your locations.

MCA: I didn't do any dialogue writing for characters. I did the revisions and contributed to the story document, the vision document and a lot of work on the area design documents which weren't the final areas that got implemented. But that was the work that I did on Wasteland 2, yeah.

JMR: The environmental descriptions in the Ag Center, were they your work or Nathan's?

MCA: I remember doing a few samples lines for that, but I don't think the final ones made it in.

JMR: How is it like working with Larian? How is it different from working with Obsidian or inXile?

MCA: The story process on Larian is as collaborative as inXile and more collaborative than Obsidian. There's a lot more writers involved in the storyline for Larian, about the same level for inXile, and what we do is we all get on to Skype and Google Documents and then we sort of have like a remote meeting, where we talk through each of the plot points one by one and try and make sure that it's compelling, it's interesting, and we just keep doing that until the story feels right. We've moved on from the story and now we're doing the player character origin story, which is kind of like the background you can choose for your character, and that's currently what I'm involved with right now. I got to write the Undead origin story, which is pretty cool.

JMR: You said some of your inspirations for Torment came from Japanese RPGs.

MCA: [laughs]

JMR: How much are you interested in Japanese culture? Do you have favorite Japanese movies or anime?

MCA: I do have a few animes that I like, I like Samurai Champloo. I also liked Cowboy Bebop. I really liked a series called Trigun. I like Attack on Titan, even through I didn't like it at first. But mostly the influence from Japanese RPGs came from how they did their companion design. What I always liked about JRPGs is I felt like they always gave you enough time to get to know the companion character and try them out before moving on to the next guy. Because some of the trap that Western RPGs fall into is they'll introduce a few characters at the beginning that you get really attached to, but then when you meet a new character you don't want to switch out because you're comfortable with the old guy. Japanese RPGs stage it so everybody gets equal screen time at the beginning, and it's staggered out. And then at the end, they let you choose, but you've been introduced to all the characters sort of at once, in stages, and I think that works a lot better.

JMR: What part of your work that was cut was the most difficult to let go of?

MCA: None of it. Part of a narrative designer's job is that you don't really get attached to anything and you're supposed to make sure that the content fits with the direction for the title. The most difficult part was how it was handled. I got to hear second-hand that it was gonna be cut and later on the creative lead apologized to me about it. But that didn't really change how the process worked. And what I... I mean, the changes happened and I was happy to make the changes but I thought the entire thing was held extremely poorly.

JMR: It was me who found out about the Van Buren trademark.

MCA: [laughs] Eh, good for you! Good job! What's up, detective?

JMR: Could you please tell us how work on the project is going?

MCA: [smiling mischievously] Oh, I couldn't say something like that! No, that would be saying too much! [laughs]

JMR: Don't you owe the Codex some troll drawings?

MCA: So I had a question about that. I actually don't know what drawings those are. I thought I'd already given them, all the troll drawings. So I drew one on Twitter and sent it to them right before this interview. So that's one less drawing, but if they have a list of stuff that I haven't delivered, please let me know.

JMR: Fans really want an RPG with MCA as lead writer again. Will that ever happen? Even if it means working for Larian, inXile or any other company that shows interest? Many of us think that when you only write a character or two, or assume a strictly supervisory role, then that waters down the Avellone experience.

MCA: So I absolutely would be a lead writer again. It depends on the company. I did not want to be a lead writer at Obsidian. I would be a lead writer at another company. The issue with Larian is they already have a story structure in place. And the same thing with inXile. But under the right circumstances I absolutely would do it again.

JMR: Great! I can't wait, I've been waiting ten years for this!

MCA: [smiling] Yeah.

JMR: What would a company need to offer you to join them? Full creative control over your projects? Something else?

MCA: [thinks for a while] So... a number of companies have offered me a great deal to do my own project. The issue is that I really can't do it right now. And the problems are... there's a lot of stuff going on with family and also I can't work anywhere full-time until all that stuff is resolved. So that's kind of a challenge.

JMR: You said during the conference that you're working on an unannounced project to be announced later this year. Is it an RPG?

MCA: Oh... I can't even say anything about it beyond that it's coming. [laughs] I think if I gave any details that actually would be too much, but shouldn't be too much longer. [laughs]

JMR: Aw... I was actually going to ask if it's a new IP or not, or are you working with a company you worked with previously or not, but you won't answer I guess...

MCA: Yeah. Unfortunately I couldn't say anything. I'd love to, I'm happy to talk about it after it's announced but...

JMR: What work of fiction you have experienced in recent months has inspired you the most, and in what way?

MCA: [thinks for quite a while] That is a good question. Um... [thinks for a while] So... what have I read recently? That actually... well, there's a few things. Oddly enough, I've been reading The Great Gatsby. [laughs] And what I really like is the metaphor usage in the book. So much so that I think about how that could be used as weapons. [laughs] The other thing is... I've been reading Brandon Sanderson's Steelheart series and I'm kind of a sucker for superheroes and supervillains. And even though I didn't like the first book, I did like the second book much more. And I'm enjoying the third book right now, mostly because the ideas they have for the supervillain powers are really interesting to read. And it's kind of fun to try and figure out what each villain's weakness is. And... so I'm enjoying that a lot.

JMR: What do you think of the approach of games like Dark Souls or Divinity: Original Sin to storytelling, where the player has to discover the plot rather than the plot shoving itself down the throat of the player? What are the advantages and disadvantages of this non-linear approach?

MCA: [surprised] Oh, okay. Yes, so... all right, so Dark Souls is one of the games that I use in the example of how visuals and very minimal prose can communicate a lot about a world, without someone talking at you. And what I really like about Dark Souls, I think, visual storytelling, they do a great job, but then with their inventory items, those also tell a story with very minimal attacks. So those are two things that I wish more narrative designers would pay attention to.

JMR: Are you good at playing Dark Souls? [couldn't resist]

MCA: Are you kidding? I'm not good at playing any games. I suck at everything! [laughs]

JMR: Well, there are no wolves in Dark Souls! [I meant wolf trash mobs. Sending MCA against Sif would be an act of cruelty]

MCA: [laughs] Yeah. Every game I play I get my ass kicked, but I still enjoy it. [laughs]

JMR: What's your dream project? Do you think you'll ever realize it? On the same note, hypothetically, if you didn't have to worry about financial returns, what game would you make?

MCA: So I don't care about financial returns anymore, because that doesn't make me happy. If I were to work on a dream project, I probably couldn't say too much about it, but it would probably have to wait for a little while until family stuff settles down, but um... it would probably not involve a lot of text. [laughs] It would probably be a story more conveyed through visuals.

JMR: How often does your feedback actually influence the final outcome of a game?

MCA: Do you mean feedback from players, or feedback from the player who'll play in the game?

JMR: No, I mean the feedback you give to other companies.

MCA: Um... [thinks for quite a while] Well, so, on Wasteland 2... we did have a story motivation meeting that... got a little debate-heavy because... no one could figure out a motivation for the Synths. Like no one... they're like, “Okay, well, we're not really sure why these guys are invading the wasteland” and I... so, during that meeting in about ten minutes I was able to break down what their motivation should be, and it was pretty simple because it was already the part of the gameplay loop. Like basically, the Synths' motivations was trying to basically convert as many humans and communities as possible to their way of thinking for spare parts. Like, that's pretty simple, but I think it just took a lot of back-and-forth discussions before that came about, and I actually don't know if that ended up being the final motivation in the game, but it certainly seemed to solve a lot of questions during that meeting. When I came to Numenera, um... [thinks for a while] I don't think that anything related to the story direction, they necessarily used for the end part of the game. The only thing that I asked to be done was just to make sure that each of the Tides you do in the game... that you feel that your interactions with those Tides was significant for the end encounter, but I think they had that covered anyway.

JMR: You actually designied the last part of Wasteland 2, the Synth base, yes? [I was trying to get information about the cut content at Seal Beach]

MCA: No... I worked on an area called the Refinery that I think got cut and then there was also um, another community, I think, near the end base but that also got downscaled at the end of the game. Most of my contributions were Highpool, Agricultural Center, and then one of the secret shrine locations, I think, was the only areas that survived.

JMR: Are there themes you do not include in your writing for fear of pissing people off?

MCA: Not people... not players. Publishers, for sure. There are certain franchises, where there are certain subjects they don't want you to talk about. And any other times I've attempted to include material that I think would be hotly debated, that's been cut.

JMR: What is more difficult for you? Creating concepts, like who is this guy, what are his motivations, his personality? Or doing the actual writing, bringing individuals to life with words?

MCA: So, doing the actual dialogue, writing, that's always the hardest. And I usually find that trying to do a concept for a character that you haven't written a word of dialogue for is sometimes a waste of time. Because once you start writing, that person becomes totally different. Like, once you start channeling the words, you don't always closely follow the concept anymore, you sort of let the character kind of pull you along where they want to go. So sometimes it ends up being different than the concept.

JMR: Which of your famous characters have ended up going in a different direction?

MCA: Um... Ulysses did. Kreia didn't. Um... the Disciple in KotOR 2 did. He turned into kind of a big pussy, but that for some reason, that's how he came out. Uh... the character Sand in Neverwinter Nights 2 was never supposed to be written that way. But then he just came out that way. Also, Grobnar in Neverwinter Nights 2 came out a lot differently and then the voice acting made him worse. Um... those are a few examples.

JMR: Creating stories you always have some ideas and motives in mind. How often does the audience misread them? Have you found any surprising interpretations of your work?

MCA: Oh yeah! So the first problem that usually occurs is someone assumes that I'm trying to push some real world political agenda or some real world religious philosophy into a character, and I never am. All I'm doing is I try and examine the world that character lives in, and then I give him a perspective. But people always seem to want to take it to a real word philosophy or religion or political agenda kind of place, when that's not the case at all. [laughs]

JMR: Well, that's what people do!

MCA: [laughs] Yeah they do, that's what they do. But then I feel bad because they make a very intelligent interpretation of what I did, and then I'm embarrassed because mine isn't very intelligent. [laughs] So that's kind of embarrassing. [laughs]

JMR: When you're not the lead designer on a game, the parts of it you're working on have to fit with somebody else's vision. What challenges does this pose? Have you ever found yourself complying with a vision you didn't like?

MCA: Do you mean, did I ever uphold like, a design direction I didn't agree with?

JMR: No, I mean motifs, themes, general concepts.

MCA: Um... [thinks for a while] That's a good question. Um... [thinks for a while] Well, I guess in Pillars of Eternity I didn't always quite understand the spirit recycling mechanic. Um... I didn't always understand how that worked with the spell system and other elements of the world. And I think the way I interpreted people living forever was a little bit different than everybody else. And also I got a little bit confused about um... well, I got confused about the fact that the central premise in Pillars is an interesting one, but I don't know if the story, including the stuff that I wrote, helps support that theme. Because in order for that theme to work, you need to emphasize how important the gods are in that world, and I never really got the sense they were really all that important.

JMR: What concept would you most like to explore in a future project? What concept do you think is overused in RPGs?

MCA: The idea of a chosen one. “Oh, I'm special”, especially when there's no real reason behind it, and... that's a problem. Another motif is, for some reasons you're the only one doing things. The rest of the world holds still while you take your time, I think that's kind of garbage. Also... [thinks for a while] This is kind of weird, but what I don't like is I feel there's a lot of games that introduce very interesting characters right from the outset, like in New Vegas, like you get Sunny Smiles and her dog. I would have liked to have her as a companion, but for some reason those characters never seem to be able to join your party which is kind of weird, and then they're kind of shuttled off and forgotten, which just is kind of bizarre. So I don't really understand why that happens, when in fact that's one of the best opportunities to introduce a companion character. And if it's up to me I try to make sure you can, but when games don't do that, that feels weird.

JMR: [flips through pages searching for the next question]

MCA: Oh, I'm sorry, also like one other thing... like, sometimes I think, uh... some writers fall into the trap that they have to explain everything to the player. Like they just give like a huge word vomit dump about like what everyone's thinking and what my grand plan is. And you know what, players aren't dumb. Like, you can seed that stuff around and players can make the logical leaps about what people's motivations are, why they want to do things, without them having to come out and say it. And sometimes when you get faced with exposition like that... I just shake my head and want to cry. Because it would have been far more interesting if you could help interpret what their motivations were and see how they came to be, rather than them just telling you how things happened. And that's kind of irritating.

JMR: When you talked... oh sorry, this is about Van Buren so I won't ask.

MCA: [laughs] I... you know, if such a project exists I would be happy to talk about it. But I can't talk about it. But good detective work, well done!

JMR: I guess you won't say anything about Autoduel either.

MCA: [laughs] Yeah. Also... no, I'm sorry, go on.

JMR: No no, say what you wanted to say!

MCA: Oh no no, I'm sorry.

JMR: You come across as a very humble guy, always good-willed towards others. Were you always like that, or is it something you learned during your life?

MCA: Uh... well, that's a kind way of interpreting it. I guess the way I would interpret it is... it's always worthwhile to be pleasant and share respect to everybody, until the moment that you realize that they don't treat you the same way. And when you suddenly realize that some people are poison, those are the people... you're not mean to them, but you just cut them out of your life. You're like, “You know what? Having you in my circle or around me or knowing anything about me has proven to be poisonous in our relationship, and I can't have you in my life anymore.” But I try and be quiet about that, but I feel everybody else deserves a fair shot and I... I wasn't the most outgoing person in the world, and I always appreciated people that were nice to me and went out of their way to make me feel welcome and invited. But with the game community everybody's like that. We all like games, we all like the same interests. It's really easy to have a conversation. I rarely meet a mean game developer or a mean game player. Like everyone's just so nice, it's not hard to be nice to people who are nice in the first place.

JMR: You said on Twitter that you were going to work with the Fallout IP at the source. What did you mean?

MCA: Fallout IP at the...?

JMR: At the source.

MCA: No no no, I wasn't going to work on it. I would prefer to work at the source, and the reason for that is because they're in control of the lore. The problem is if you're... if you're one step removed from any franchise, whether it's Star Wars or Fallout or whatever, if you're not there, at the place that owns the actual lore, there is a lot of hoops you have to jump through to get stuff approved, and it's exhausting. So if I were to work on Fallout, what I want to do is actually work at the place where the lore is being developed. Not have it passed off to me for approvals and back and forth because... I don't think that's very efficient.

JMR: In a cut ending for Torment, there's a movie showing the Nameless One waking up in the mortuary without his memories. What player actions were meant to lead to this outcome?

MCA: [thinks for a while] Wait, there's a cut movie that shows that?

JMR: I don't know if it was a movie or if it was a planned ending...

MCA: That may have been an ending planned early on, I actually don't remember. But I do know that it was almost so impossible to get resources to do a movie. We did not have the freedom to do a lot of those. So we were actually lucky to get the movies that we did. And... Torment was a pretty small team, especially compared to Baldur's Gate [laughs]. So it's possible that was planned... but I don't remember that clearly, and also I'm guessing we probably just would never have the resources to do it anyway. So I'm not surprised if that would have been cut probably halfway through development. But it's certainly a viable ending. It would make sense to me.

JMR: Do you have any other unannounced projects besides the ones we spoke about before? Let's say, how many unannounced things are you working on now?

MCA: [thinks for a while] Quite a few. [laughs] And that's all I can say.

JMR: More than three?

MCA: Quite a few. [laughs]

JMR: Did you do any work on Dwarfs?

MCA: No... so, my work on Dwarfs was... I reviewed the work that Kevin Saunders and Brian Mitsoda did. Because Brian Mitsoda was the lead story writer for Dwarfs. And I think he did a really good job of sort of categorizing what each dwarf's personality was, what their character arc and abilities were. And Kevin did a good job of managing the project. My involvement was mostly on an advisory capacity, where I'm like “Okay here's my thoughts on the story, like, here's elements that I like, here's things that I think are working really well, here are things I think need to be shored up a little bit.” That was basically my involvement on Dwarfs.

JMR: Were the dwarfs party members?

MCA: Yes.

JMR: All of them?

MCA: Yeah, but you could only switch out two at a time, so like, you have a main character and then you'd be able to choose two dwarfs to join you in a party. And each of them had special powers and abilities, and you'd just switch them out.

JMR: Who was the villain?

MCA: [thinks for a while] Not sure I can say. Um... the dwarfs I'm gonna talk about but the villain I will leave for another time. [laughs] It was a really weird franchise, though. The fact that someone wanted to do Snow White and the Seven Dwarves as an RPG... I was like, “All right, that's weird.” [laughs] But then, they wanted to do it... a thousand years before Snow White. So you saw like, all the history that led up to the Snow White world, and that was really cool. And then I like got it, I'm like, ”Oh, okay, I understand why it's cool now”, so... but initially I didn't think it was very cool.

JMR: Was it a light-hearted or dark RPG?

MCA: Kind of around the middle.

JMR: There were talks ten years ago with White Wolf about Obsidian making a World of Darkness game in the Neverwinter Nights 2 engine. Do you have any idea what story you would have told in this game?

MCA: No... um, I don't even, I... gosh... so I wouldn't have done that. I don't recall it... I don't think it lends itself well to an isometric game, per se. I guess I'd have to see more elements of the design, but I don't know if I would have done a Neverwinter World of Darkness, but this is outside of... like, this is just my thoughts. Like, I don't recall anything like that nor would I have supported something like that.

JMR: You worked for some time on Hidden. Could you tell us something more about it?

MCA: What was this?

JMR: Hidden.

MCA: [thinks for a while, looks puzzled] Oh... wow, you're really good. No, I can't say anything about that. Unfortunately. [thinks for a while] Wow, you're good.

JMR: Actually, I got it yesterday from Feargus.

MCA: Oh, and what did Feargus say about it? Because then I can go off of what Feargus said.

JMR: [I related what I remembered of Feargus' description to Chris]

MCA: [thinks for a while] Oh, yeah... wow... yeah, that didn't happen. [looks at some distant point on the horizon] God... I can't say anything more, it'd just go bad.

JMR: What was the storyline for the third KotOR game? What would the player do in the Sith Empire? Was it going to be structured like the first two KoTORs: prologue, four planets and then the ending? Or something else?