RPG Codex Review: Torment: Tides of Numenera

RPG Codex Review: Torment: Tides of Numenera

Codex Review - posted by felipepepe on Sun 12 March 2017, 08:50:47

Tags: inXile Entertainment; Torment: Tides of NumeneraWhat does one life matter? What can change the nature of man? And did Torment: Tides of Numenera, InXile's spiritual successor to Planescape: Torment, deliver on its promises?

For the past two weeks these have been the questions puzzling RPG fans - or at least those who aren't playing Horizon: Zero Dawn, Nier: Automata or just waiting for Mass Effect: Andromeda, that is. The press loved InXile's latest game, but the audience seems less convinced. Sales have been poor next to previous big Kickstarter RPGs, anger erupted from cut content and the reception has been mixed both on our forums and on Steam (two places that rarely agree). Making a successor to the Codex's #1 RPG of all time is obviously no simple task, so esteemed contributor Prime Junta took the job of measuring InXile's success. Here's an excerpt from the full piece:

Read the full article: RPG Codex Review: Torment: Tides of Numenera

For the past two weeks these have been the questions puzzling RPG fans - or at least those who aren't playing Horizon: Zero Dawn, Nier: Automata or just waiting for Mass Effect: Andromeda, that is. The press loved InXile's latest game, but the audience seems less convinced. Sales have been poor next to previous big Kickstarter RPGs, anger erupted from cut content and the reception has been mixed both on our forums and on Steam (two places that rarely agree). Making a successor to the Codex's #1 RPG of all time is obviously no simple task, so esteemed contributor Prime Junta took the job of measuring InXile's success. Here's an excerpt from the full piece:

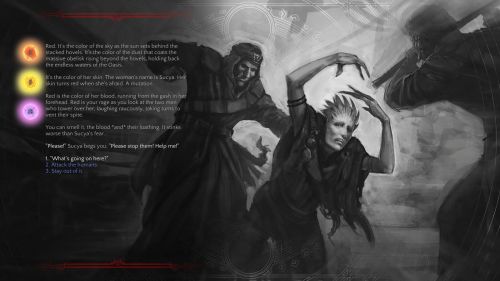

The fatal flaw of Torment: Tides of Numenera is timidity. It is terrified of stepping out of the shadow of its ancestor, to proudly do its own thing. Instead, it imagines Torment can be captured in a formula. It apes its forms without understanding its substance. If Planescape: Torment is a monk struggling with a kôan, "What can change the nature of a man?" a red-hot iron ball in his throat which he can neither swallow nor spit out, Tides is a philosophy freshman crying into his red wine, in love with the profundity of his navel. Planescape: Torment's characters embody that central question: the succubus who took a vow of chastity, the enslaved warrior-monk from a people defined by their escape from slavery, the fragment of a collective consciousness who developed a sense of self. Tides' characters... talk about it. They're painted sticks parroting lines written for them, not flesh-and-blood characters living, breathing that question.

For example, consider companion vision quests. I achieved the best outcomes for all of the companions I had with me without even paying much attention to them, as the game goes out of its way to make absolutely sure you don't miss anything. If you've forgotten to talk to your companion, they'll remind you. If you've missed a quest trigger, the character in the next step of that vision quest will react anyway, even helpfully asking you to bring that character to him if he isn't with you at the time. Keep clicking on things, and eventually you'll get a menu to click on, giving your companion ending A, B, or C. The conversations themselves are shallow, and it doesn't matter much what you say in them as you end up in the same place anyway. You don't have any reason to care, beyond shallow feel-good humanitarianism. This is only similar in form with Planescape: Torment, where companion dilemmas are also resolved primarily through conversation. There, however, you won't even meet one of your potential companions if you don't, out of pure curiosity, buy a trinket from a merchant and then fiddle with it, attempting to figure out what it does, and exploring the Unbroken Circle of Zerthimon with Dak'kon reveals as many searingly painful truths about you as it does about him.

For example, consider companion vision quests. I achieved the best outcomes for all of the companions I had with me without even paying much attention to them, as the game goes out of its way to make absolutely sure you don't miss anything. If you've forgotten to talk to your companion, they'll remind you. If you've missed a quest trigger, the character in the next step of that vision quest will react anyway, even helpfully asking you to bring that character to him if he isn't with you at the time. Keep clicking on things, and eventually you'll get a menu to click on, giving your companion ending A, B, or C. The conversations themselves are shallow, and it doesn't matter much what you say in them as you end up in the same place anyway. You don't have any reason to care, beyond shallow feel-good humanitarianism. This is only similar in form with Planescape: Torment, where companion dilemmas are also resolved primarily through conversation. There, however, you won't even meet one of your potential companions if you don't, out of pure curiosity, buy a trinket from a merchant and then fiddle with it, attempting to figure out what it does, and exploring the Unbroken Circle of Zerthimon with Dak'kon reveals as many searingly painful truths about you as it does about him.

Read the full article: RPG Codex Review: Torment: Tides of Numenera

[Review by Prime Junta]

Somewhere, some time, in an office or on an online hangout, a group of veteran writers and game designers got together to discuss their philosophical, thoughtful, text-heavy computer role-playing game. In that meeting, they decided that the game needed a skill check. That skill check: Healing, Lore: Natural. The action: gently massaging the rim of a giant alien’s sphincter. The objective: getting it to relax, so you and your party can crawl in.

By that point, the people who made that decision must have long since lost their way, forgetting everything they knew about what makes a game work. For they did know. They must have known: their previous work proves it. Kevin Saunders and George Ziets of Mask of the Betrayer. Brian Mitsoda of Vampire: Bloodlines. Colin McComb and Adam Heine, both veterans of Planescape: Torment. Last but definitely not least, Planescape: Torment’s creator Chris Avellone, drafted onto the team to “review and provide feedback on all creative elements of the game, including the story, characters, and areas.” [link]

Moment to moment, Torment: Tides of Numenera is a chore to interact with. Characters respond sluggishly. The camera jumps around at the slightest provocation. Hot spots respond poorly to clicks. The user interface is a busy and overly-animated mess. Its combat interludes – dubbed Crises – are ridiculously exploitable but tedious, as crowds of (often) continuously spawning enemies take an eternity to march around the field while taking their turn.

Most cRPGs have exploitable systems: it is inherent to any game which has systems complex enough to be enjoyable to play with. Tides, though, manages to have systems that are at the same time painfully simple, and painfully exploitable. This is because two features in the system almost entirely invalidate any character-building choices you might want to make: Effort, and the possibility to use any party member for almost any skill check. The Effort mechanic has you spending points from a Pool (Might, Speed, or Intellect) to boost your chances of success in whatever task you’re attempting. The cost in points is reduced by your Edge in the stat in question. This means that all you have to do to guarantee success in all skill checks past the first hour or so of the game is to specialise one of your party members in each stat, and then pick the right one for each check. This is beyond bad cRPG system design, it’s downright ridiculous – enjoyable only for players who want to feel awesome all the time, invariably succeeding at everything to which they turn their hand.

Fans of the Numenera pen-and-paper RPG are likely to be disappointed by Tides as well. The Numenera system never was a good fit for a cRPG, but it would have been possible to make a cRPG system that retained some of its unique features while adding the kind of complexity computers can easily handle. Cyphers – powerful single-use “magic” items that can do practically anything – are supposed to be front and centre; in Tides, they are at best a side dish, rarely worth using instead of a character’s own abilities. Moreover, many items that ought to be cyphers (specifically, those restoring Health or Pool points) are just ordinary consumables that don’t count toward a character’s cypher limit. Numenera’s unique rest mechanic is gone, replaced by bog-standard healing potion spam. The outcome is an uncomfortable mix of some of Numenera’s worst aspects and unimaginative, generic cRPG mechanics.

Some of these problems could be offset if encounters were well-designed, interesting, and exciting. There is a good underlying idea there: that you're able to do stuff besides combat, while in combat. You can talk to your enemies or interact with the environment, and in many cases there are non-violent ways to resolve the situation. Sadly, most encounters – dubbed Crises – consist of a massive mob of mostly identical enemies taking turns to hammer you. In some of them, they continuously spawn. All but one or two optional ones can be trivialised simply by spending some Effort to hide, and then doing whatever you need to do to resolve the Crisis – or, as in the case of one climactic fight in the endgame, just staying put as the enemy marches around aimlessly until the "survive this long to win" timer runs out. Worse, it takes ages for the enemy mobs to finish their turn. Quantity is not a substitute for quality, or an enjoyable, explorable, crisply-responding, fast-moving turn-based combat system.

"A world like no other" (as the Kickstarter pitched it) relies on atmosphere to pull the player in. Here, too, Tides fails to live up to its promise. With a few exceptions, maps are shoddily put-together with ill-fitting textures and flat, uniform lighting straight from a 1980s office. And it's not like there are a huge number of them: compared to either its current Kickstarter peers or Planescape Torment, Tides is a pretty small game as far as map space goes. There is a noticeable dearth of interiors: the Sagus Cliffs quest hub has two, not counting "dungeon" areas, and the Bloom isn't much better. In some cases it feels like these were last-minute cuts: for example, we have a clerk working on the stairs to the government building rather than inside in an office like you would expect.

Sound design is similarly insipid: you would imagine that the inside of a city-sized interdimensional predator sounds pretty scary, but all Tides manages is a few half-hearted hisses and gurgles spiced up with an altogether human heartbeat probably lifted off an FX collection. Mark Morgan, the composer for the original Planescape: Torment, wrote fifty tracks for the game, but somehow none of them manage to be the least bit memorable. They become background ambience or a generic combat soundtrack, not the emotional high points they are in Planescape: Torment or Fallout.

Tides' quests often have multiple resolutions, which sometimes have consequences down the line. The designs, however, are incredibly pat. If you need to find a bucketful of nanocrystal chicken teeth for the Grand Snord of Qweebloth, you can be sure that on the very same map, or at most the one right next to it, you will find a destitute merchant desperate to unload a shipment. While there isn't an actual quest compass, your journal will have a helpful tip suggesting you ask around the Impecunious Bazaar, since you're obviously too dim to figure it out yourself. Any sense of achievement or discovery you might have will get killed off the second, third, or fourth time everything "accidentally" lines up perfectly for you to solve your impossible problem of the day. The game is soporifically easy. At no point did I ever feel the least bit challenged, intellectually, tactically, ethically, philosophically, or otherwise, if frustration caused by a misclick during a Crisis doesn't count.

The biggest let-down, however, is the writing. It is a potluck of disparate ingredients that fails to make a coherent whole, while at the same time going on and on endlessly about a single theme. It is wordy, loaded with unnecessary adjectives and reams of description, most of which is of things you can see on the screen right in front of you. It is not improved by thinly-disguised backer NPCs referencing Don Quixote or lecturing about alien sex, or constant wink-wink-nudge-nudge references to Planescape: Torment. Everybody has something to say, but you're given precious few reasons to listen. With a few exceptions, it is uninspiring, dull, lacking in tension or any of the mystery or wonder that was the driving force of its ostensible spiritual ancestor. The game gives away the plot in the introductory infodump, and one half-hearted plot twist aside, the eventual dénouement is utterly predictable, and its resolution approaches Mass Effect 3 levels of let-down. This is a combat game for players who hate combat; a skill game for people who hate to fail; a story game for people who measure story by word count.

More words than the Bible. About as uneven writing also. Could stand cutting about the Old Testament’s worth.

The fatal flaw of Torment: Tides of Numenera is timidity. It is terrified of stepping out of the shadow of its ancestor, to proudly do its own thing. Instead, it imagines Torment can be captured in a formula. It apes its forms without understanding its substance. If Planescape: Torment is a monk struggling with a kôan, "What can change the nature of a man?" a red-hot iron ball in his throat which he can neither swallow nor spit out, Tides is a philosophy freshman crying into his red wine, in love with the profundity of his navel. Planescape: Torment's characters embody that central question: the succubus who took a vow of chastity, the enslaved warrior-monk from a people defined by their escape from slavery, the fragment of a collective consciousness who developed a sense of self. Tides' characters... talk about it. They're painted sticks parroting lines written for them, not flesh-and-blood characters living, breathing that question.

For example, consider companion vision quests. I achieved the best outcomes for all of the companions I had with me without even paying much attention to them, as the game goes out of its way to make absolutely sure you don't miss anything. If you've forgotten to talk to your companion, they'll remind you. If you've missed a quest trigger, the character in the next step of that vision quest will react anyway, even helpfully asking you to bring that character to him if he isn't with you at the time. Keep clicking on things, and eventually you'll get a menu to click on, giving your companion ending A, B, or C. The conversations themselves are shallow, and it doesn't matter much what you say in them as you end up in the same place anyway. You don't have any reason to care, beyond shallow feel-good humanitarianism. This is only similar in form with Planescape: Torment, where companion dilemmas are also resolved primarily through conversation. There, however, you won't even meet one of your potential companions if you don't, out of pure curiosity, buy a trinket from a merchant and then fiddle with it, attempting to figure out what it does, and exploring the Unbroken Circle of Zerthimon with Dak'kon reveals as many searingly painful truths about you as it does about him.

The same applies to your own quest. As you're chasing the Big Bad, you endure a ceaseless barrage of "but what does one life matter?" from a huge cast of bit players. In the final scene, you get to pick an item from a list: your choice for how your life mattered, that famous "legacy" inXile so relentlessly markets. Then you get to read a paragraph of text on an ending slide. Once again, the writers have completely failed to grasp what Planescape: Torment was all about. In its magnificent dénouement, it doesn't ask you to pick from a list of answers to choose what can change the nature of a man: that question was long since asked and answered, and represented only a stage on your journey. Instead, if you have struggled hard enough, it leaves you in a place where that question no longer matters. The monk has passed his kôan. The red-hot iron ball never was. That is true artistry, and something that cannot be recreated by slavishly aping forms.

Torment: Tides of Numenera is a mystery and a tragedy. A mystery: how could a five-million-dollar Kickstarter executed by veterans of the industry with so much experience and talent result in a fiasco of this magnitude? A tragedy: that such exciting, off-the-beaten-track, and creative ideas could fail so cruelly in the execution, and that the hopes of so many people could be so brutally crushed.

The brief flashes of creativity, ambition, and intelligence the game occasionally exhibits only serve to set its general failure in high relief. A handful of maps look good. The Bloom with its Maws is a genuinely cool idea, and some of that did make it all the way to the game. Some Crises can be resolved several ways: by talking, by interacting with the environment, sometimes in non-obvious ways. Some objectives have multiple ways to reach them, and many quests have multiple possible resolutions. Sometimes failing to solve a puzzle the “right” way gives surprising results. There is some consequence between quests; solving one problem one way might make it easier, or harder, to solve another problem later down the line. There are two somewhat-relatable companion characters in the game: one a Minsc with an Avellonian twist, another… a Lost Child who Shapes Gods. There are a few Meres – choose-your-own-adventure text interludes inside a character’s memories – which rise above the general amateur-hour level, notably one at the end of a long-running sidequest. These islands of quality are a credit to their creators because that standard was clearly not a requirement from the people in charge of the project. They are a sad reminder of what could have – should have – been.

The game falls far short of its promise. The Kickstarter campaign and its subsequent updates showed off carefully-crafted, dynamic scenes with animated elements, parallax layers, dynamic lighting, an old-school UI, full, competently-acted voiceover, and hand-painted, beautiful and characterful concept art and portraits. All of this was watered down or removed outright. We were shown a rotating water wheel; we got a few animated, looping textures; parallax layers were replaced with a hastily-cloned background image masked with a quick fog effect; moody, dynamic lighting by even, flat illumination. Standards everywhere are appallingly low. This does not look, sound, feel, read, or play like a five-million-dollar labour of love by veteran industry professionals. It is not the Planescape: Torment successor we were hoping for. It is not even a tribute. It is barely even a pastiche. Only time will tell if we ever will see one. In the meantime, the Brothel for the Slaking of Intellectual Lusts remains open for business, as Ravel spins her webs in her maze and the Dustmen silently toil in the Mortuary, and in the Fortress of Regrets transcendence and a ghost of unrequited love await a grim planewalker scarred with a thousand deaths.

~ * ~

When I returned to the Kickstarter pitch, I almost got excited all over again. This game was going to be so beautiful...

Valley of Broken Promises

Live orchestra. Cut. Ruins of Ossiphagan. Cut. The Toy. Another companion. The Order of Flagellants and Austerities. Cut, cut cut. Lacunae, Hall of Lingering Reflections, yet another companion, another exit from the Castoff’s labyrinth, Voluminous Codex, the Oasis of M’Ra Jolios, player stronghold, Fathoms, foci, legacies, joinable factions, Italian localisation, all gone. Concept art where HR Giger meets the pre-Raphaelites turned into clumsy photo overpaints. Teaser videos with an old-school UI, full voiceover, and moody, dynamic lighting turned into silent scenes on flatly lit, hastily put-together maps.

To make it worse, inXile attempted to sweep all these cuts under the rug. They hoped that somehow the tens of thousands of fans who pledged for the project and cheered it on through every update wouldn’t notice, or wouldn’t care. When caught, they attempted to weasel out of some of them, claiming that the endgame area is the player stronghold, or that they didn’t really cut the Oasis, just decided to make the Bloom the second major hub – this, after running a successful post-Kickstarter funding drive specifically to “restore George Ziets’ Bloom design and fully implement it according to his original vision.” [link]

If inXile ever wants to stick its snout in the crowdfunding trough again, it needs to regain the trust of its fans. After a betrayal of this magnitude, that is going to be a tall order. A good start would be to come clean: to candidly explain what went wrong and where, how that five million in crowdfunding money was spent, and how a group this good could have such low standards for the quality of their work, and ultimately produce so little. They had the budget. They had the talent. They even had a ready-made isometric cRPG engine and asset production pipeline. What happened here?

Or hey, they could always sell DLC armour to console players. Guess that’ll work too.

Somewhere, some time, in an office or on an online hangout, a group of veteran writers and game designers got together to discuss their philosophical, thoughtful, text-heavy computer role-playing game. In that meeting, they decided that the game needed a skill check. That skill check: Healing, Lore: Natural. The action: gently massaging the rim of a giant alien’s sphincter. The objective: getting it to relax, so you and your party can crawl in.

By that point, the people who made that decision must have long since lost their way, forgetting everything they knew about what makes a game work. For they did know. They must have known: their previous work proves it. Kevin Saunders and George Ziets of Mask of the Betrayer. Brian Mitsoda of Vampire: Bloodlines. Colin McComb and Adam Heine, both veterans of Planescape: Torment. Last but definitely not least, Planescape: Torment’s creator Chris Avellone, drafted onto the team to “review and provide feedback on all creative elements of the game, including the story, characters, and areas.” [link]

Moment to moment, Torment: Tides of Numenera is a chore to interact with. Characters respond sluggishly. The camera jumps around at the slightest provocation. Hot spots respond poorly to clicks. The user interface is a busy and overly-animated mess. Its combat interludes – dubbed Crises – are ridiculously exploitable but tedious, as crowds of (often) continuously spawning enemies take an eternity to march around the field while taking their turn.

Most cRPGs have exploitable systems: it is inherent to any game which has systems complex enough to be enjoyable to play with. Tides, though, manages to have systems that are at the same time painfully simple, and painfully exploitable. This is because two features in the system almost entirely invalidate any character-building choices you might want to make: Effort, and the possibility to use any party member for almost any skill check. The Effort mechanic has you spending points from a Pool (Might, Speed, or Intellect) to boost your chances of success in whatever task you’re attempting. The cost in points is reduced by your Edge in the stat in question. This means that all you have to do to guarantee success in all skill checks past the first hour or so of the game is to specialise one of your party members in each stat, and then pick the right one for each check. This is beyond bad cRPG system design, it’s downright ridiculous – enjoyable only for players who want to feel awesome all the time, invariably succeeding at everything to which they turn their hand.

Fans of the Numenera pen-and-paper RPG are likely to be disappointed by Tides as well. The Numenera system never was a good fit for a cRPG, but it would have been possible to make a cRPG system that retained some of its unique features while adding the kind of complexity computers can easily handle. Cyphers – powerful single-use “magic” items that can do practically anything – are supposed to be front and centre; in Tides, they are at best a side dish, rarely worth using instead of a character’s own abilities. Moreover, many items that ought to be cyphers (specifically, those restoring Health or Pool points) are just ordinary consumables that don’t count toward a character’s cypher limit. Numenera’s unique rest mechanic is gone, replaced by bog-standard healing potion spam. The outcome is an uncomfortable mix of some of Numenera’s worst aspects and unimaginative, generic cRPG mechanics.

Some of these problems could be offset if encounters were well-designed, interesting, and exciting. There is a good underlying idea there: that you're able to do stuff besides combat, while in combat. You can talk to your enemies or interact with the environment, and in many cases there are non-violent ways to resolve the situation. Sadly, most encounters – dubbed Crises – consist of a massive mob of mostly identical enemies taking turns to hammer you. In some of them, they continuously spawn. All but one or two optional ones can be trivialised simply by spending some Effort to hide, and then doing whatever you need to do to resolve the Crisis – or, as in the case of one climactic fight in the endgame, just staying put as the enemy marches around aimlessly until the "survive this long to win" timer runs out. Worse, it takes ages for the enemy mobs to finish their turn. Quantity is not a substitute for quality, or an enjoyable, explorable, crisply-responding, fast-moving turn-based combat system.

"A world like no other" (as the Kickstarter pitched it) relies on atmosphere to pull the player in. Here, too, Tides fails to live up to its promise. With a few exceptions, maps are shoddily put-together with ill-fitting textures and flat, uniform lighting straight from a 1980s office. And it's not like there are a huge number of them: compared to either its current Kickstarter peers or Planescape Torment, Tides is a pretty small game as far as map space goes. There is a noticeable dearth of interiors: the Sagus Cliffs quest hub has two, not counting "dungeon" areas, and the Bloom isn't much better. In some cases it feels like these were last-minute cuts: for example, we have a clerk working on the stairs to the government building rather than inside in an office like you would expect.

Sound design is similarly insipid: you would imagine that the inside of a city-sized interdimensional predator sounds pretty scary, but all Tides manages is a few half-hearted hisses and gurgles spiced up with an altogether human heartbeat probably lifted off an FX collection. Mark Morgan, the composer for the original Planescape: Torment, wrote fifty tracks for the game, but somehow none of them manage to be the least bit memorable. They become background ambience or a generic combat soundtrack, not the emotional high points they are in Planescape: Torment or Fallout.

Tides' quests often have multiple resolutions, which sometimes have consequences down the line. The designs, however, are incredibly pat. If you need to find a bucketful of nanocrystal chicken teeth for the Grand Snord of Qweebloth, you can be sure that on the very same map, or at most the one right next to it, you will find a destitute merchant desperate to unload a shipment. While there isn't an actual quest compass, your journal will have a helpful tip suggesting you ask around the Impecunious Bazaar, since you're obviously too dim to figure it out yourself. Any sense of achievement or discovery you might have will get killed off the second, third, or fourth time everything "accidentally" lines up perfectly for you to solve your impossible problem of the day. The game is soporifically easy. At no point did I ever feel the least bit challenged, intellectually, tactically, ethically, philosophically, or otherwise, if frustration caused by a misclick during a Crisis doesn't count.

The biggest let-down, however, is the writing. It is a potluck of disparate ingredients that fails to make a coherent whole, while at the same time going on and on endlessly about a single theme. It is wordy, loaded with unnecessary adjectives and reams of description, most of which is of things you can see on the screen right in front of you. It is not improved by thinly-disguised backer NPCs referencing Don Quixote or lecturing about alien sex, or constant wink-wink-nudge-nudge references to Planescape: Torment. Everybody has something to say, but you're given precious few reasons to listen. With a few exceptions, it is uninspiring, dull, lacking in tension or any of the mystery or wonder that was the driving force of its ostensible spiritual ancestor. The game gives away the plot in the introductory infodump, and one half-hearted plot twist aside, the eventual dénouement is utterly predictable, and its resolution approaches Mass Effect 3 levels of let-down. This is a combat game for players who hate combat; a skill game for people who hate to fail; a story game for people who measure story by word count.

More words than the Bible. About as uneven writing also. Could stand cutting about the Old Testament’s worth.

The fatal flaw of Torment: Tides of Numenera is timidity. It is terrified of stepping out of the shadow of its ancestor, to proudly do its own thing. Instead, it imagines Torment can be captured in a formula. It apes its forms without understanding its substance. If Planescape: Torment is a monk struggling with a kôan, "What can change the nature of a man?" a red-hot iron ball in his throat which he can neither swallow nor spit out, Tides is a philosophy freshman crying into his red wine, in love with the profundity of his navel. Planescape: Torment's characters embody that central question: the succubus who took a vow of chastity, the enslaved warrior-monk from a people defined by their escape from slavery, the fragment of a collective consciousness who developed a sense of self. Tides' characters... talk about it. They're painted sticks parroting lines written for them, not flesh-and-blood characters living, breathing that question.

For example, consider companion vision quests. I achieved the best outcomes for all of the companions I had with me without even paying much attention to them, as the game goes out of its way to make absolutely sure you don't miss anything. If you've forgotten to talk to your companion, they'll remind you. If you've missed a quest trigger, the character in the next step of that vision quest will react anyway, even helpfully asking you to bring that character to him if he isn't with you at the time. Keep clicking on things, and eventually you'll get a menu to click on, giving your companion ending A, B, or C. The conversations themselves are shallow, and it doesn't matter much what you say in them as you end up in the same place anyway. You don't have any reason to care, beyond shallow feel-good humanitarianism. This is only similar in form with Planescape: Torment, where companion dilemmas are also resolved primarily through conversation. There, however, you won't even meet one of your potential companions if you don't, out of pure curiosity, buy a trinket from a merchant and then fiddle with it, attempting to figure out what it does, and exploring the Unbroken Circle of Zerthimon with Dak'kon reveals as many searingly painful truths about you as it does about him.

The same applies to your own quest. As you're chasing the Big Bad, you endure a ceaseless barrage of "but what does one life matter?" from a huge cast of bit players. In the final scene, you get to pick an item from a list: your choice for how your life mattered, that famous "legacy" inXile so relentlessly markets. Then you get to read a paragraph of text on an ending slide. Once again, the writers have completely failed to grasp what Planescape: Torment was all about. In its magnificent dénouement, it doesn't ask you to pick from a list of answers to choose what can change the nature of a man: that question was long since asked and answered, and represented only a stage on your journey. Instead, if you have struggled hard enough, it leaves you in a place where that question no longer matters. The monk has passed his kôan. The red-hot iron ball never was. That is true artistry, and something that cannot be recreated by slavishly aping forms.

Torment: Tides of Numenera is a mystery and a tragedy. A mystery: how could a five-million-dollar Kickstarter executed by veterans of the industry with so much experience and talent result in a fiasco of this magnitude? A tragedy: that such exciting, off-the-beaten-track, and creative ideas could fail so cruelly in the execution, and that the hopes of so many people could be so brutally crushed.

The brief flashes of creativity, ambition, and intelligence the game occasionally exhibits only serve to set its general failure in high relief. A handful of maps look good. The Bloom with its Maws is a genuinely cool idea, and some of that did make it all the way to the game. Some Crises can be resolved several ways: by talking, by interacting with the environment, sometimes in non-obvious ways. Some objectives have multiple ways to reach them, and many quests have multiple possible resolutions. Sometimes failing to solve a puzzle the “right” way gives surprising results. There is some consequence between quests; solving one problem one way might make it easier, or harder, to solve another problem later down the line. There are two somewhat-relatable companion characters in the game: one a Minsc with an Avellonian twist, another… a Lost Child who Shapes Gods. There are a few Meres – choose-your-own-adventure text interludes inside a character’s memories – which rise above the general amateur-hour level, notably one at the end of a long-running sidequest. These islands of quality are a credit to their creators because that standard was clearly not a requirement from the people in charge of the project. They are a sad reminder of what could have – should have – been.

The game falls far short of its promise. The Kickstarter campaign and its subsequent updates showed off carefully-crafted, dynamic scenes with animated elements, parallax layers, dynamic lighting, an old-school UI, full, competently-acted voiceover, and hand-painted, beautiful and characterful concept art and portraits. All of this was watered down or removed outright. We were shown a rotating water wheel; we got a few animated, looping textures; parallax layers were replaced with a hastily-cloned background image masked with a quick fog effect; moody, dynamic lighting by even, flat illumination. Standards everywhere are appallingly low. This does not look, sound, feel, read, or play like a five-million-dollar labour of love by veteran industry professionals. It is not the Planescape: Torment successor we were hoping for. It is not even a tribute. It is barely even a pastiche. Only time will tell if we ever will see one. In the meantime, the Brothel for the Slaking of Intellectual Lusts remains open for business, as Ravel spins her webs in her maze and the Dustmen silently toil in the Mortuary, and in the Fortress of Regrets transcendence and a ghost of unrequited love await a grim planewalker scarred with a thousand deaths.

~ * ~

When I returned to the Kickstarter pitch, I almost got excited all over again. This game was going to be so beautiful...

Live orchestra. Cut. Ruins of Ossiphagan. Cut. The Toy. Another companion. The Order of Flagellants and Austerities. Cut, cut cut. Lacunae, Hall of Lingering Reflections, yet another companion, another exit from the Castoff’s labyrinth, Voluminous Codex, the Oasis of M’Ra Jolios, player stronghold, Fathoms, foci, legacies, joinable factions, Italian localisation, all gone. Concept art where HR Giger meets the pre-Raphaelites turned into clumsy photo overpaints. Teaser videos with an old-school UI, full voiceover, and moody, dynamic lighting turned into silent scenes on flatly lit, hastily put-together maps.

To make it worse, inXile attempted to sweep all these cuts under the rug. They hoped that somehow the tens of thousands of fans who pledged for the project and cheered it on through every update wouldn’t notice, or wouldn’t care. When caught, they attempted to weasel out of some of them, claiming that the endgame area is the player stronghold, or that they didn’t really cut the Oasis, just decided to make the Bloom the second major hub – this, after running a successful post-Kickstarter funding drive specifically to “restore George Ziets’ Bloom design and fully implement it according to his original vision.” [link]

If inXile ever wants to stick its snout in the crowdfunding trough again, it needs to regain the trust of its fans. After a betrayal of this magnitude, that is going to be a tall order. A good start would be to come clean: to candidly explain what went wrong and where, how that five million in crowdfunding money was spent, and how a group this good could have such low standards for the quality of their work, and ultimately produce so little. They had the budget. They had the talent. They even had a ready-made isometric cRPG engine and asset production pipeline. What happened here?

Or hey, they could always sell DLC armour to console players. Guess that’ll work too.

There are 644 comments on RPG Codex Review: Torment: Tides of Numenera