RPG Codex Review: Jagged Alliance 3

RPG Codex Review: Jagged Alliance 3

Codex Review - posted by Infinitron on Sat 26 August 2023, 18:31:32

Tags: Haemimont Games; Jagged Alliance 3; THQ NordicIn retrospect, it's pretty wild that the long-awaited third installments of two different beloved roleplaying series from the 1990s were released within the span of three weeks this year. Haemimont Games' Jagged Alliance 3 has now been completely overshadowed by that other game, but given the franchise's track record over the past two decades, their achievement is no less impressive. A Jagged Alliance sequel received with near-unanimous positivity on our forums (give or take an ArchAngel). Such a feat could not go unrecognized, and so we present our extensive review, written by talented community member Strange Fellow. He finds that despite certain questionable combat mechanics, occasionally overly campy writing, and an overabundance of loot containers, Haemimont's game is a Jagged Alliance title worthy of the name. Here's an excerpt:

Read the full article: RPG Codex Review: Jagged Alliance 3

You’ll spend a lot of time juggling operations in the strategic view, but the real meat of the game takes place in the tactical view, where you control each individual mercenary in turn-based combat. This is where Jagged Alliance made a name for itself, and where any sequel absolutely needs to deliver.

And what do you know – it does. The game once again copies a number of its systems from Jagged Alliance 2, and since that is probably the pinnacle of the genre, as you’d expect it all works very nicely. The control you have over your mercenaries is very granular, and you can specify everything from whether they should be running, crouching or lying down, to exactly how many action points they should spend zeroing in on an enemy, as well as what part of the body to aim for. Unconventionally (though not for the franchise), chance to hit is not displayed, and you will have to eyeball each shot, while mercs provide helpful comments whenever they think a shot is likely to succeed or fail. It’s a great system, which strikes a good balance between uncertainty and feedback, and it’s nice to see it make its return.

There are other such nuances to the combat as well, which are not new to the series but are rarely seen elsewhere, especially these days. With the option to target body parts comes location-specific damage; so a shot to the leg will decrease movement, a shot to the arms will decrease accuracy, and so on. Guns fire bullets with real trajectories and real penetration, which means that a missed shot might hit something else, or a shot with a high-penetration weapon might travel right through the target and hit something else behind him. Cover can be destroyed, visual contact can be broken with smoke, characters can be suppressed by gunfire and flashbangs, and combatants can get panicked and lose their turn entirely.

Energy and morale are also in, although the energy and morale metres of the previous game have been replaced by a ladder of cumulative status effects. If forced to operate for a long time without a break, mercs will gain the “Tired” status, reducing their maximum action points by 1. If forced to keep going, they will eventually become “Exhausted”, losing another action point. On top of that, exhausted characters are liable to fall unconscious if they’re hit with more energy-draining attacks. Likewise with morale: it can drop to low or very low, decreasing AP, if mercs take significant damage or if someone dies, and rise when mercs score good kills, complete quests or progress in the campaign. Overall, the effect works out to be about the same as in the previous game, if presented in a slightly more cumbersome way.

One aspect of combat that deserves particular praise is the level of environmental destruction the game supports. You can break a lot of scenery in Jagged Alliance 3. Certain things you will not be able to blow up, such as the skeletons of larger buildings as well as bridges and other things essential to the traversability of the map. Still, the level of damage that you can do to most structures is impressive and a delight to play with. Level the second floor of a building with a rocket launcher, and have enemies rain down from above into the waiting arms of your knife-wielding melee specialist on the first floor. Blow the roof off a building with a grenade, then chuck a second one through the hole into the cluster of enemies huddled inside. It is simply great fun, and makes explosives specialists very valuable additions to your team, quite apart from their direct damage potential. There are plenty of sector designs that provide good opportunities to make use of their potential, too. It doesn’t reach the level of mayhem that you can cause in X-COM: Apocalypse or Silent Storm – the kings of the genre if all you want to do is raze the entire map – but it’s miles above most of the competition.

[...] There are other issues as well, and the most serious ones all have to do with how combat is initiated. Firstly, there’s the matter of stealth mode, and more broadly, enemy awareness in general. Enemies in this game are deaf, dumb and blind to a ridiculous degree. The vision range of your own mercs is more than twice as long as that of the enemies, which ensures that you'll always spot them before they spot you. Even in broad daylight you can freely run around in the open without having to be particularly careful. Engage stealth mode as well, which at the cost of movement speed makes your mercs even harder to detect, and you can run rings around enemies without them noticing. Now add the detection system, where enemies have detection bars that need to fill up before they’re considered to have spotted you, and the result is that the only time you won’t get to initiate combat yourself is if a patrol happens to walk right into one of your mercs while you’re busy controlling someone else.

And that’s not all. Alongside the stealth system there is a stealth kill system. Essentially, there is a percentage chance of an attack made from stealth to result in an instant kill. There are mercs who via perks and high stats have a higher chance of achieving stealth kills, and with these you are all but guaranteed that the first attack you make results in a fatality. Did I mention that you can re-enter stealth in the middle of combat? And that silenced weapons are so easy to come by that you can have several after the very first tutorial sector? It is an absurd system, and fundamentally warps balance in favour of long-range weapons – sniper rifles, in other words. The tragedy is that the balance in the utility of different weapon types is quite good otherwise, and every weapon type has its niche. It is a shame that by far the best strategy in terms of preserving the safety of your mercs is to ignore them. Perhaps bring along a single machine gun when things get hairy, but otherwise stick to silenced rifles and pick enemies off from stealth. The game doesn’t have to be played this way, but any other approach is far, far more likely to land your mercs in trouble.

The developers obviously realised that setting up devastating stealth ambushes was inordinately powerful, so they came up with a solution. Unfortunately their solution is, once again, terrible. What they did was allow the enemies a small quasi-turn at the beginning of combat to reposition themselves. In other words, whenever you start combat by shooting a bad guy, all his friends are allowed a moment to scurry for cover without there being anything you can do about it. This destroys any potential of a well-executed ambush – or it would, if you could not set up overwatch over every enemy and watch them get shot as they do their little scramble. In any case, it takes away your control of the situation. It would seem to be a natural thing, in a game about tactical operations with a small squad of elite soldiers who are vastly outnumbered, to reward the player for setting up a good ambush. Clearly, though, in Jagged Alliance 3 this is so absurdly easy to do that the player can’t be allowed to do it, so control must be taken away from him in however arbitrary a fashion. This is a textbook example of how bad design begets bad design.

And what do you know – it does. The game once again copies a number of its systems from Jagged Alliance 2, and since that is probably the pinnacle of the genre, as you’d expect it all works very nicely. The control you have over your mercenaries is very granular, and you can specify everything from whether they should be running, crouching or lying down, to exactly how many action points they should spend zeroing in on an enemy, as well as what part of the body to aim for. Unconventionally (though not for the franchise), chance to hit is not displayed, and you will have to eyeball each shot, while mercs provide helpful comments whenever they think a shot is likely to succeed or fail. It’s a great system, which strikes a good balance between uncertainty and feedback, and it’s nice to see it make its return.

There are other such nuances to the combat as well, which are not new to the series but are rarely seen elsewhere, especially these days. With the option to target body parts comes location-specific damage; so a shot to the leg will decrease movement, a shot to the arms will decrease accuracy, and so on. Guns fire bullets with real trajectories and real penetration, which means that a missed shot might hit something else, or a shot with a high-penetration weapon might travel right through the target and hit something else behind him. Cover can be destroyed, visual contact can be broken with smoke, characters can be suppressed by gunfire and flashbangs, and combatants can get panicked and lose their turn entirely.

Energy and morale are also in, although the energy and morale metres of the previous game have been replaced by a ladder of cumulative status effects. If forced to operate for a long time without a break, mercs will gain the “Tired” status, reducing their maximum action points by 1. If forced to keep going, they will eventually become “Exhausted”, losing another action point. On top of that, exhausted characters are liable to fall unconscious if they’re hit with more energy-draining attacks. Likewise with morale: it can drop to low or very low, decreasing AP, if mercs take significant damage or if someone dies, and rise when mercs score good kills, complete quests or progress in the campaign. Overall, the effect works out to be about the same as in the previous game, if presented in a slightly more cumbersome way.

One aspect of combat that deserves particular praise is the level of environmental destruction the game supports. You can break a lot of scenery in Jagged Alliance 3. Certain things you will not be able to blow up, such as the skeletons of larger buildings as well as bridges and other things essential to the traversability of the map. Still, the level of damage that you can do to most structures is impressive and a delight to play with. Level the second floor of a building with a rocket launcher, and have enemies rain down from above into the waiting arms of your knife-wielding melee specialist on the first floor. Blow the roof off a building with a grenade, then chuck a second one through the hole into the cluster of enemies huddled inside. It is simply great fun, and makes explosives specialists very valuable additions to your team, quite apart from their direct damage potential. There are plenty of sector designs that provide good opportunities to make use of their potential, too. It doesn’t reach the level of mayhem that you can cause in X-COM: Apocalypse or Silent Storm – the kings of the genre if all you want to do is raze the entire map – but it’s miles above most of the competition.

[...] There are other issues as well, and the most serious ones all have to do with how combat is initiated. Firstly, there’s the matter of stealth mode, and more broadly, enemy awareness in general. Enemies in this game are deaf, dumb and blind to a ridiculous degree. The vision range of your own mercs is more than twice as long as that of the enemies, which ensures that you'll always spot them before they spot you. Even in broad daylight you can freely run around in the open without having to be particularly careful. Engage stealth mode as well, which at the cost of movement speed makes your mercs even harder to detect, and you can run rings around enemies without them noticing. Now add the detection system, where enemies have detection bars that need to fill up before they’re considered to have spotted you, and the result is that the only time you won’t get to initiate combat yourself is if a patrol happens to walk right into one of your mercs while you’re busy controlling someone else.

And that’s not all. Alongside the stealth system there is a stealth kill system. Essentially, there is a percentage chance of an attack made from stealth to result in an instant kill. There are mercs who via perks and high stats have a higher chance of achieving stealth kills, and with these you are all but guaranteed that the first attack you make results in a fatality. Did I mention that you can re-enter stealth in the middle of combat? And that silenced weapons are so easy to come by that you can have several after the very first tutorial sector? It is an absurd system, and fundamentally warps balance in favour of long-range weapons – sniper rifles, in other words. The tragedy is that the balance in the utility of different weapon types is quite good otherwise, and every weapon type has its niche. It is a shame that by far the best strategy in terms of preserving the safety of your mercs is to ignore them. Perhaps bring along a single machine gun when things get hairy, but otherwise stick to silenced rifles and pick enemies off from stealth. The game doesn’t have to be played this way, but any other approach is far, far more likely to land your mercs in trouble.

The developers obviously realised that setting up devastating stealth ambushes was inordinately powerful, so they came up with a solution. Unfortunately their solution is, once again, terrible. What they did was allow the enemies a small quasi-turn at the beginning of combat to reposition themselves. In other words, whenever you start combat by shooting a bad guy, all his friends are allowed a moment to scurry for cover without there being anything you can do about it. This destroys any potential of a well-executed ambush – or it would, if you could not set up overwatch over every enemy and watch them get shot as they do their little scramble. In any case, it takes away your control of the situation. It would seem to be a natural thing, in a game about tactical operations with a small squad of elite soldiers who are vastly outnumbered, to reward the player for setting up a good ambush. Clearly, though, in Jagged Alliance 3 this is so absurdly easy to do that the player can’t be allowed to do it, so control must be taken away from him in however arbitrary a fashion. This is a textbook example of how bad design begets bad design.

Read the full article: RPG Codex Review: Jagged Alliance 3

[Review by Strange Fellow]

Jagged Alliance 3 review

Not at all in the same way that Carlsberg is probably the best beer in the world, Jagged Alliance is probably the best turn-based tactics video game series in the world. It is a perfect blend of small-scale squad management, hilarious action-movie homages and excellent turn-based combat. Jagged Alliance 2 might be my favourite game of all time.

That’s precisely why my reaction when a new game was announced was: not this shit again. The Jagged Alliance games that have been released this century are best described in words not appropriate for a family-friendly magazine such as this. Suffice it to say that each of the studios that made them was forced to shutter its doors more or less immediately, in a rare example of karmic justice in the video game industry.

This time, the live grenade was handed to Bulgarian outfit Haemimont Studios. But this time, it was not going to be a spinoff. This time it was going to be the real deal, in the form of a numbered entry. Marketing tricks aside, when news began to surface about the game, it became clear that this was indeed a more ambitious attempt at a true sequel than the drivel we’d been served for the past 20 years. They’d even snagged Ian Currie. It was at least worth a closer look.

The game takes place in the former French colony of Grand Chien, which has been taken over by a terrorist group called the Légion, led by a mysterious character known only as the Major. The Légion have kidnapped the president, and who better to save him than Laptop Guy and his private mercenary company of choice, the Association of International Mercenaries, A.I.M. for short.

As usual, saving the day is achieved through taking over the entire country by shooting a busload of enemies, while keeping the campaign running via careful budgeting. Like previous games in the series, Jagged Alliance 3 operates on two levels, blending strategy and RPG elements: the strategic view is used to command squads around the world map and engage in various automated operations, while the tactical view is used for fighting and chatting with NPCs.

Don’t Cry For Me Grand Chien

The strategic layer will be very familiar to those who have played Jagged Alliance 2, as it has been replicated almost exactly. The game world is divided into a square grid of sectors, and in true Chutes and Ladders fashion the game starts you off as far away from your goal as possible. The mercenaries at your disposal are grouped into squads, which you can move around from sector to sector in pausable real time. Most sectors have enemies in them, and once your mercs have cleared a sector of enemies, it’s considered to be under your control.

Different sectors provide different bonuses when conquered. The most important type of sector is the diamond mine, of which there are five in the game and which represent your only steady source of income. The amount of cash each mine generates is tied to the loyalty score of the nearest city, which can be raised by liberating city sectors, repelling enemy counterattacks, and doing favours for its inhabitants. Once a city sector is under your control, you can train militia which will protect the sector against enemy offensives. The reason you need cities and mines is that mercenaries don’t work for free; they will need to be paid on a regular basis, and if you can’t afford their salaries they’ll pack their things and leave.

The main thrust of a standard campaign is to traverse the country sector by sector, clearing cities and mines and establishing your own troops to protect them, as you slowly paint the map blue. In addition to training militia, you can have your mercenaries train each other, bandage their wounds, and repair their gear. If this all sounds familiar, it’s because not a thing has changed about this dynamic since the previous game. It’s even still the case that militia can only be trained so much by mercenaries, with further advancement only possible through combat, and that mines will eventually run dry after a period (now this will happen to every mine, rather than just one).

Having said this, there are a few minor additions to the formula. The country of Grand Chien is not a single landmass, and as such, not all travel can be done on foot. There are now port sectors, which allow your mercs to take boat rides to any water-adjacent sector. Unfortunately, ports aren’t as strategically important as they sound. They don’t as a rule function as city sectors, so training militia for them is not possible, and the enemy will not station troops in them or send attack squads after them. The whole system ends up being barely an inconvenience, and the usual approach of clicking on whichever sector you want to travel to works the same whether the destination is accessible by road or sea. Taking a boat costs money, but this too is negligible.

A more interesting addition is outpost sectors. These are usually heavily guarded, and when under enemy control periodically generate attack squads which are sent out to retake nearby player-controlled sectors. They are prime targets for both the player and the enemy, and will provide some of the most challenging battles outside of set-piece events, especially if you happen to go in at a time when it’s full of fresh attack squads. Also roaming around the map are diamond shipments generated by region-controlled mines and heading out of the country. These can be intercepted for a significant cash prize. While you would by no means call Jagged Alliance 3 a deep strategic simulation, these additions are a welcome step towards making the world feel more dynamic as compared to its predecessors. The implementation of enemy designated attack squads also facilitates the execution of a certain major plot event in a very pleasing fashion, by having stuff actually happen in a systemic way rather than simply flipping script switches.

It is a shame that the experience is marred by an abysmal UI. While the UI for the combat view is functional enough, the strategic UI is a mess of submenus and lack of clarity. If you’ve played Jagged Alliance 2, you will recall that all mercenaries under your employ will be shown on the same page, and assigning them tasks and moving them about was as simple as two mouse clicks. Here, you will need to navigate a submenu called Operations, where you can assign tasks on a per-squad basis. This menu is extremely unwieldy. For example, the repair operation lets you queue up items to be fixed, but this queue is extremely short, so to repair all your gear you will often need to start the repairing operation several times as the mercs finish the four items you’ve assigned them to. What’s more, mercs will only repair gear in their squad’s possession, which means that if you happen to have multiple squads in the same sector, the second squad will need to drop their gear if they want it repaired. As for travelling, you cannot change the route mid-travel. You will first need to cancel travel, wait as the mercs make their way to the centre of the nearest sector, then resume with the updated route. While you’re doing this, other operations continue and may be completed while you’re fiddling, pausing the game constantly as you wonder why nothing’s happening. You can't tell at a glance how many militiamen there are in a sector, or even where your own squads are. The time progression has only one speed, which is sometimes too fast and sometimes awfully slow. In general, every single action has been made to require a few more mouse clicks and just a little more hassle as compared to the previous game, while the actual functionality hasn’t changed at all.

Another issue with the strategic part of the game is money. You start off with a little bit of cash, which is enough to hire a couple of the less expensive mercenaries for a couple of weeks. But eventually their contracts will run out, and you’ll also want to hire more bodies, which means that one of your primary objectives at the start of the game will be to generate income. It's a good system that keeps you from dawdling, at least in theory. And in the early parts of the game money can indeed be tight, especially if you’ve hired some of the more expensive mercs, or if you’re forced to spend significant time resting and healing your squad. However, this very quickly stops being a concern. The issue is very simple: mines generate too much money. If you’ve taken over two of the five mines in Grand Chien, you’re essentially set for life, and there’s no real reason to pursue the other ones, at least until one of yours runs dry.

That’s half the reason why money is so abundant. The other half is that there’s really nothing to spend it on. There is no Bobby Ray’s or a Micky O’Brien in this game, on whom you could unload some of your cash in exchange for weapons and other items; your only real expense will be mercenary contracts, and that’s not enough. Even if you invest in several squads and fill them up with the most expensive mercenaries you will not have to worry. To be sure, you could buy yourself quite a bit of leeway in the previous games as well, but it was never as easy as it is here. Presumably, mine income is something that can be tuned very easily, so by the time you read this there may well be a patch or a mod that improves things. As it is, the balance is off.

Tacticulations

You’ll spend a lot of time juggling operations in the strategic view, but the real meat of the game takes place in the tactical view, where you control each individual mercenary in turn-based combat. This is where Jagged Alliance made a name for itself, and where any sequel absolutely needs to deliver.

And what do you know – it does. The game once again copies a number of its systems from Jagged Alliance 2, and since that is probably the pinnacle of the genre, as you’d expect it all works very nicely. The control you have over your mercenaries is very granular, and you can specify everything from whether they should be running, crouching or lying down, to exactly how many action points they should spend zeroing in on an enemy, as well as what part of the body to aim for. Unconventionally (though not for the franchise), chance to hit is not displayed, and you will have to eyeball each shot, while mercs provide helpful comments whenever they think a shot is likely to succeed or fail. It’s a great system, which strikes a good balance between uncertainty and feedback, and it’s nice to see it make its return.

There are other such nuances to the combat as well, which are not new to the series but are rarely seen elsewhere, especially these days. With the option to target body parts comes location-specific damage; so a shot to the leg will decrease movement, a shot to the arms will decrease accuracy, and so on. Guns fire bullets with real trajectories and real penetration, which means that a missed shot might hit something else, or a shot with a high-penetration weapon might travel right through the target and hit something else behind him. Cover can be destroyed, visual contact can be broken with smoke, characters can be suppressed by gunfire and flashbangs, and combatants can get panicked and lose their turn entirely.

Energy and morale are also in, although the energy and morale metres of the previous game have been replaced by a ladder of cumulative status effects. If forced to operate for a long time without a break, mercs will gain the “Tired” status, reducing their maximum action points by 1. If forced to keep going, they will eventually become “Exhausted”, losing another action point. On top of that, exhausted characters are liable to fall unconscious if they’re hit with more energy-draining attacks. Likewise with morale: it can drop to low or very low, decreasing AP, if mercs take significant damage or if someone dies, and rise when mercs score good kills, complete quests or progress in the campaign. Overall, the effect works out to be about the same as in the previous game, if presented in a slightly more cumbersome way.

One aspect of combat that deserves particular praise is the level of environmental destruction the game supports. You can break a lot of scenery in Jagged Alliance 3. Certain things you will not be able to blow up, such as the skeletons of larger buildings as well as bridges and other things essential to the traversability of the map. Still, the level of damage that you can do to most structures is impressive and a delight to play with. Level the second floor of a building with a rocket launcher, and have enemies rain down from above into the waiting arms of your knife-wielding melee specialist on the first floor. Blow the roof off a building with a grenade, then chuck a second one through the hole into the cluster of enemies huddled inside. It is simply great fun, and makes explosives specialists very valuable additions to your team, quite apart from their direct damage potential. There are plenty of sector designs that provide good opportunities to make use of their potential, too. It doesn’t reach the level of mayhem that you can cause in X-COM: Apocalypse or Silent Storm – the kings of the genre if all you want to do is raze the entire map – but it’s miles above most of the competition.

A little more on sectors: they are no longer uniformly sized, which means that unimportant sectors, not belonging to a city nor offering any special services, can often be quite small. Other sectors, particularly important ones like military bases, are much bigger – bigger indeed than in any of the previous games. Sectors are also quite varied, with everything from featureless savannah to urban streets and fortified military complexes. Additionally, the transition to fully-3D environments means multi-story buildings, guard towers, and natural elevation which serves to further distinguish sectors. There is also a day and night cycle as well as a weather system, which can affect combat in different ways – night reduces vision range, rain muffles noise, and so on. All in all, the variety is excellent, and no two important sectors feel the same.

It all adds up into a very enjoyable combat system which feels and controls like Jagged Alliance 2 in more ways than not. It is particularly good in bigger, more protracted encounters as the fighting settles into a rhythm. Injured characters can’t be healed instantly, as taking significant damage causes wounds which decrease maximum HP – though, disappointingly, don’t have an impact on AP and won’t start bleeding like they used to do. It nevertheless means that keeping a wounded merc in the fight is a risky proposition, and you will want to prioritise retreating with those while calling in others to bandage them, as the rest hold the line against enemies. The combat is generally a little too easy even on the hardest difficulty, so these situations will be rarer than they should; when they happen, though, they’re a perfect example of what makes combat in these games so compelling.

However, not all is roses. Alongside all the good stuff, there is a set of problems which drags the experience down significantly. One of these is how turn interruptions are handled. The series, up until now, has allowed each combatant to save up unspent action points from his team’s turn, giving him the chance to interrupt the opponents’ turn and use his remaining AP for whatever. Jagged Alliance 3 instead implements an overwatch system. Characters can now use their unspent AP to specify an overwatch area, and will then open fire on any enemy who enters it.

On the face of it, this is not a strictly negative change – the main effect is a reduction of control, and as such ought to make interruptions less devastating for both player and computer. However, there is one big problem: most enemies suck at using overwatch. While you, the player, will frequently blanket an area with overwatch zones (it is one of the most effective ways to play the game, as enemies running towards you like lemmings is one area where the game conforms to tradition), enemy troops will not make much use of this mechanic at all. Usually, it is only machine gunners who will take overwatch positions, and even then, only if they can place the overwatch cone directly over one of your mercs. They will never overwatch in anticipation of your approach, ever. Remember how you had to be careful when entering buildings or rounding corners in previous games, because there might be an enemy standing ready to interrupt you just on the other side? You will be able count on one hand the number of times this happens to you in Grand Chien. The elimination of this worry puts a definite damper on close quarters operations. The good news is that later on in the game, more advanced enemies with appreciably better AI show up, and these do at least make liberal use of overwatch even if they’re not carrying machine guns. But the problem persists that you will not have to worry about unwittingly running into enemy fire during your turn.

There are other issues as well, and the most serious ones all have to do with how combat is initiated. Firstly, there’s the matter of stealth mode, and more broadly, enemy awareness in general. Enemies in this game are deaf, dumb and blind to a ridiculous degree. The vision range of your own mercs is more than twice as long as that of the enemies, which ensures that you'll always spot them before they spot you. Even in broad daylight you can freely run around in the open without having to be particularly careful. Engage stealth mode as well, which at the cost of movement speed makes your mercs even harder to detect, and you can run rings around enemies without them noticing. Now add the detection system, where enemies have detection bars that need to fill up before they’re considered to have spotted you, and the result is that the only time you won’t get to initiate combat yourself is if a patrol happens to walk right into one of your mercs while you’re busy controlling someone else.

And that’s not all. Alongside the stealth system there is a stealth kill system. Essentially, there is a percentage chance of an attack made from stealth to result in an instant kill. There are mercs who via perks and high stats have a higher chance of achieving stealth kills, and with these you are all but guaranteed that the first attack you make results in a fatality. Did I mention that you can re-enter stealth in the middle of combat? And that silenced weapons are so easy to come by that you can have several after the very first tutorial sector? It is an absurd system, and fundamentally warps balance in favour of long-range weapons – sniper rifles, in other words. The tragedy is that the balance in the utility of different weapon types is quite good otherwise, and every weapon type has its niche. It is a shame that by far the best strategy in terms of preserving the safety of your mercs is to ignore them. Perhaps bring along a single machine gun when things get hairy, but otherwise stick to silenced rifles and pick enemies off from stealth. The game doesn’t have to be played this way, but any other approach is far, far more likely to land your mercs in trouble.

The developers obviously realised that setting up devastating stealth ambushes was inordinately powerful, so they came up with a solution. Unfortunately their solution is, once again, terrible. What they did was allow the enemies a small quasi-turn at the beginning of combat to reposition themselves. In other words, whenever you start combat by shooting a bad guy, all his friends are allowed a moment to scurry for cover without there being anything you can do about it. This destroys any potential of a well-executed ambush – or it would, if you could not set up overwatch over every enemy and watch them get shot as they do their little scramble. In any case, it takes away your control of the situation. It would seem to be a natural thing, in a game about tactical operations with a small squad of elite soldiers who are vastly outnumbered, to reward the player for setting up a good ambush. Clearly, though, in Jagged Alliance 3 this is so absurdly easy to do that the player can’t be allowed to do it, so control must be taken away from him in however arbitrary a fashion. This is a textbook example of how bad design begets bad design.

The combination of the scramble turn and the general inattentiveness of enemies produces other silliness as well. If you happen to be running a squad more oriented around close quarters combat, a strategy that is just as effective – although not as risk-free – is to simply run at a cluster of enemies full tilt. They are so slow to react that by the time combat starts, your mercs will be standing right next to them. The mandatory scramble for cover will happen, but nobody will run very far, and enemies will very rarely attack or overwatch, meaning that you start combat in close proximity to enemies that have no hope of retaliating during your turn. With a properly built squad, mopping them up is a routine exercise, and the only thing you will have to worry about are reinforcements from further away. In other words, you’re free to choose your flavour of exploit, all because of two poorly thought-out systems which, ironically, were presumably put in place to make the start of combat less frustrating. The fact is that they’re way more frustrating because they’re so dumb.

As a consequence of the above, by far the best part of combat is when player and enemy compete on more or less equal terms – that is, after combat has started, both sides have found their footing, and the turns pass normally. To be fair, this is how it has always been: the best moments in the previous games (and, I would argue, in all such games) are also when an encounter has had time to settle, and the player is forced to react to enemy turns by heading off advances, bandaging the wounded and trying to find ways for your own guys to safely move forward. As I’ve already mentioned, this is where Jagged Alliance 3 is at its most engaging. The further you get in the game, the more the combat shines, as set-piece maps get bigger, you get more tools to play with, and enemies become more threatening and more numerous. It culminates in an end-game that brings out the absolute best the game has to offer, with player and enemy mortar fire, explosives, smoke grenades and overwatch zones blanketing the battlefield and waves of bad guys bearing down on your mercs. Those are the highlights – but even early on, for all its problems, combat in this game is more often than not great fun.

Igor came to the wrong neighbourhood. | The Geneva convention is more like a set of guide lines, anyway.

RPG stands for rocket-propelled grenade

Even though fighting is obviously the main dish, there are other things to do in the tactical view as well. Once the dust settles, you can choose to engage with the game’s RPG elements and solve people’s problems through dialogue instead. There’s always been some debate as to whether the Jagged Alliances could truly be called role-playing games. With this one, the RPG credentials have been strengthened considerably, both in terms of character development and the way characters interact with the world.

Let’s start with quests. The previous games had them, but this game has a lot more of them. In fact, the focus on side quests and NPC interaction in general is arguably where the third game sets itself most apart from its predecessors. Firstly, it has a proper dialogue system such as you would find in full-blooded RPGs, complete with explicit skill and stat checks. Secondly, it has more than a fair bit of choice and consequence. Some of the larger quests also have multiple parts to them and will require you to visit sectors all over the map. The upshot is that you’ll spend a lot of time talking to NPCs and solving their problems for them.

One of the biggest quests in the game deals with M.E.R.C., the rival company of A.I.M. from the previous game. You're told early on that the guys from M.E.R.C. were hired some time before you were and for the same mission, and needless to say, they failed miserably. Finding out what happened to that ill-fated venture forms the basis of a series of side quests as you follow the journeys of several M.E.R.C. mercenaries across Grand Chien. This is entirely optional, but amounts to several hours’ worth of unique content in several different sectors. More: two of the five diamond mines in the game also have side quests attached to them, as they’re held by third parties who seize the opportunity to use you for their own ends before they’ll hand over their respective deeds. The same is true of the central hospital of the region, whose associated side quest can be considered this game’s equivalent of the alien mine from Jagged Alliance 2. In fact, every city has at least a few side quests for your mercs to complete, and many other important sectors have people in them who require your help.

The quests are generally competently written and follow the semi-serious, campy style of the rest of the series, but occasionally veer too far into silliness. You will encounter your usual shopkeepers, head hunters, mob bosses and tourists in distress, but also treasure-sniffing chickens and old lady gangs. The game is also rather too fond of its references, and there are sectors dedicated entirely to, among other things, Mad Max, a Cthulhu-worshipping cult, and a poem by Edgar Allan Poe. There isn’t anything clever about these references. They’re just there for the player to, as it were, see what they did there. This is about as lazy as video game writing gets, and that’s saying a lot. Fortunately they're not too common. Other questlines are much better, like the aforementioned hunt for M.E.R.C., which, if followed to its conclusion, culminates in one of the game’s best fights, while also tying into the main quest in an important way. You also have the choice of how it should be resolved, and your decision is reflected in the ending slides (yes, this game has ending slides). There are other quests as well which tie into the main plot – or other side quests – in unexpected but pleasing ways.

Mechanically, too, everything is competently done. Several quests have time limits, which work very well with the time economy that already exists in the strategic view. Again the M.E.R.C. business is an example: carry on with the campaign for too long, and relevant characters might simply be killed by enemies before you get a chance to talk to them. There are also plenty of skill checks around which can influence the resolution of quests (or decide if quests will be available to you in the first place). This means that you’ll want to hire specialists in each of the skills if you want to squeeze maximum content out of the game. Overall, the game ticks all the boxes you’d expect from a full-blooded CRPG, but without really excelling in any area. As for the main story, it’s a tad more involved than usual, and even features a plot twist, but it still remains largely in the background, and progresses almost incidentally as you conquer more and more of the map.

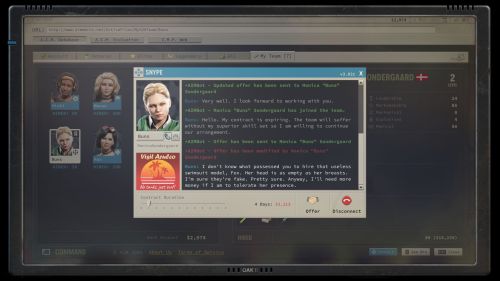

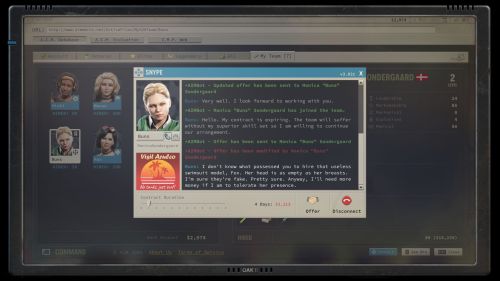

Now let’s turn to the playable characters. The uptick in the amount of time you’re expected to spend in conversation is reflected in the design of the mercenaries you can recruit, whose personalities are more fleshed-out than they’ve been previously. Mercs will frequently interject in conversation, making their opinions heard on a variety of subjects. Most of these interjections are pure flavour, but some can have more tangible effects. For example, having a merc who is a “Psycho”, a personality tag which is reserved for aggressive mercs such as Meltdown and Fidel, will sometimes provide opportunities to intimidate NPCs. Other personalities come with other benefits. This is a very enjoyable feature, which makes interacting with NPCs feel more dynamic than in most RPGs. As mentioned, the writing is generally fine, not terrible but not anything spectacular either, so the added fun of having your mercs bicker with the NPCs is very welcome, since it makes all the talking a lot more engaging than it otherwise would have been. It also increases replayability. In fact I would argue that this feature single-handedly takes dialoguing from being tedious to pleasant.

Proper effort has been made in other areas as well to give mercs proper characterisation. They each have colleagues they like and dislike, and will leave if they’re made to work with people they hate. They’ll also leave or demand a pay raise for a variety of other reasons, such as being idle for too long, getting injured too often or not killing enough bad guys. They will also chat with each other during moments of downtime. There are a whole lot of these little details, which, like in the previous games, makes not only the choice of individual mercs but also of which mercs to pair up an entertaining headache. After two and a half playthroughs, it doesn’t feel like I’ve seen half of all the unique interactions that mercs have between each other. It’s clear that a lot of effort has been put into this area of the game, and it’s effort well spent.

It would be even better, however, if the quality of each individual mercenary were less uneven. In general, Jagged Alliance 3 noticeably ramps up the pastiche factor. This has decidedly mixed results. One example of where the writing falls flat is Thor Kaufmann, a mercenary first appearing in Jagged Alliance 2. In that game, Thor was a vegetarian, and had a bit of a New Age vibe about him, but like most A.I.M. members, he was first and foremost a professional mercenary. In Jagged Alliance 3, however, hardly a single line of Thor’s dialogue is exempt from mentions of chakras, meditation and spiritual energy, to the point that his role as a hired killer feels entirely incidental. Not all characters are thus flanderised, but in the worst cases it is egregious. To be sure, there were some highly colourful characters in the previous games as well, and the fact that their personalities have changed is not in itself an issue; the problem is that mercs in this game have a lot more lines, so hearing the same joke repeated over and over again gets exponentially more tiresome.

Fortunately, these are the exception rather than the rule. The majority of mercs are enjoyable to have along, with a few standouts who produce eminently quotable lines of the kind you’d remember from the previous games. Some characters are fleshed out in natural ways – for example, Barry Unger is now a devout Catholic who will speak up, in his trademark halting English, when the conversation turns to religion. In other cases, the increased cheese factor works to the character’s benefit. It helps that the voice acting is of consistently high quality. Overall, the game succeeds quite well in providing the same sort of experience the previous games did, where you discover your own favourites as you play and where every squad configuration will lead to a unique campaign.

Igor is a good starting merc – his high health means that even if he gets knocked down, he will get up again. | Buns is more stuck-up than ever.

But more important than how characters sound is how they play. The core of the character system is unchanged from previous games, with each merc having physical stats in the form of health, strength, dexterity, agility and wisdom, as well as skills: marksmanship, mechanics, explosives, medical and leadership. Stats are the primary way by which mercs are distinguished from each other, and most have one skill as their area of expertise, while some are jacks-of-all-trades. Skills are raised by use throughout the game.

But there's a little more to it this time, as the roster has been given additional depth here as well. In addition to their stats, all mercenaries also now come with special traits as well as their own unique talent, which can affect various parts of the game. For example, Peter “Wolf” Sanderson’s talent speeds up all operations in the strategic view, such as militia training or weapon repair. Leili “Livewire” Idrisi’s talent, meanwhile, will reveal all enemy positions in a sector if the player has previously gathered intelligence about it. Traits are not unique but have similar effects; examples include “Ambidextrous” which boosts dual-wielding accuracy, and “Teacher” which speeds up militia training. Talents and traits vary wildly in usefulness. Some are game-alteringly powerful, like Livewire’s (you can imagine how much of an advantage it is to have every enemy position revealed at all times). Others are more reasonable, such as Kyle “Shadow” Simmons being able to run while in stealth mode, which is powerful but not outrageously so, while also being thematically appropriate.

In addition to unique talents, there is also a common perk tree that you can choose from whenever a merc levels up. Perks are purely combat-oriented, and each is tied to a particular stat, so you have your agility tree, your strength tree and so on. Examples of perk effects include improved critical chance with each aim level, 15 HP temporary hit points on a successful melee attack, or the ability to dodge the first enemy attack in a turn by falling prone. There are a variety of active and passive effects that will suit different roles – some improve damage, critical hit chance or accuracy in certain circumstances, while others provide temporary boosts in HP, AP or free movement. Particularly, the perk tree is friendly to melee characters, who will be able to accrue a lot of free movement and temporary hit points with the right perks, and the highest tier of perks offer such things as guaranteed critical hits with melee attacks, which is extremely powerful. Every role has its set of perks they really want, though, and many perks are also generally useful. Access to each perk is gated behind a stat threshold, and for a merc to be able to choose from the highest tier for a particular stat he will need a very high score. This means that mercs with high physical stats, on top of being tougher, stronger and faster, also have access to better perks later in the game.

If you want to shop outside of A.I.M., you can choose to make a single customised merc of your own through the I.M.P. website, whom you won’t have to pay a salary and who will never leave. This option provides an opportunity to fill any skill gaps in your squad as well as serving as a main character of sorts, if you prefer that. Taking the I.M.P. is not mandatory, however, and the poor portrait selection and horribly dull voice acting makes it much less interesting than A.I.M. mercs.

If you’re a purist, you may turn your nose up at the heightened emphasis on such elements as perks, traits, unique abilities, temporary HP and guaranteed crits in a Jagged Alliance game. All I can say is that they are at least well designed. They’re decently balanced and are not boring, there’s always a choice of good options whenever a merc levels up, and they provide real opportunities to specialise a merc for a particular job, be it stealthy ambusher, critical hit sharpshooter, speedy close-range fighter or resilient melee bulwark. What’s more, perks generally serve to improve the effectiveness of abilities mercs already have, rather than add new ones. Only one perk adds a new active ability, in the form of an attack that cancels overwatch. The rest simply make the stuff you’re already doing – moving, attacking, avoiding damage, and using items – more effective. A couple of the unique traits are too powerful, such that they warp the experience around them, but in general both traits and perks are implemented well. Crucially, they don’t exist merely to pave over the gaps of a bad combat system, because it would work well enough without them.

Now we come to the final way to develop your squad, which is through the acquisition of phat loot. There is a wide arsenal of weapons at the player’s disposal, divided into different types, each of which functions about like you’d expect: pistols are most common early on, and have low AP costs for attacking, but poor range; SMGs are like pistols, but fully automatic; knives are knives – they’re for stabbing people with; assault rifles are jacks-of-all-trades, machine guns are unwieldy but can fire off a lot of bullets very quickly, while shotguns and rifles excel at short and long range, respectively. (As usual, the video game shotgun is nothing at all like the real thing, but more like a very long melee weapon that can hit multiple enemies). There are also heavy-duty weapons like RPGs (the rocket-launching kind) and mortars.

Here, too, there are additions which will rankle if you’re a purist. In addition to its innate characteristics, each weapon type now comes with a unique special attack. SMGs have “Run and Gun”, which allows the wielder to fire off three short bursts while moving. Rifles can “Pin Down” an enemy, which lets the wielder spend the opposition’s turn taking aim, and if the target is still in view when the turn passes back to the player, take a free shot with increased accuracy and critical hit chance. Machine guns are the most devastating – they can be mounted in place, which makes the user unable to move but sets up overwatch over a specified area. While in this configuration, machine guns have high accuracy and, most significantly, can make a whole lot of overwatch attacks per turn. This ability is very strong, and it is usually less effective to have a machine gunner spend his turn firing than to find a good place to set up his gun ready to unleash hell upon the enemies as they attempt to make their approach. All weapon types are viable even into the end-game, and through perks it is possible to specialise mercs for any particular weapon.

As you’d expect, there is a selection of increasingly better guns of each type to be found as you progress in the game, along with a fair few unique named weapons, which sport improved damage, range, or crit chance over the normal versions. There is also a decently complex weapon modification system, which allows the fitting of scopes, stocks, handles and such onto compatible weapons. These modifications don’t have to be found, but are instead magicked into being from a miscellaneous “Parts” resource. Some advanced modifications do require additional components besides, but most require only Parts. And while kitting out a snazzy weapon with additional snazzy attachments can be fun, the system of Parts comes with some weaknesses. Remember I mentioned that silencers are too easy to come by? That’s because they only cost Parts. Then there is the fact that in most cases, a fully modified weapon will outclass a better weapon without modifications. This isn’t strictly a problem, as better weapons are often better precisely because they can fit more mods – but it also means that different types and tiers of guns will be more similar than they need to be, just because their innate characteristics are secondary to the fact that what they really are is an amalgam of modifications, and many of those modifications are the same across all weapons.

Scopes come with a variety of effects, like additional aim levels, decreased aiming costs or thermal vision.

Finally, the introduction of Parts brings us neatly onto a wider issue: the clicking.

The clicking

So you’ve arrived in a sector, killed the bad guys, and solved the civilians’ problems. Is there anything else to do? Yes there is: click on a whole lot of things.

If there is one activity Jagged Alliance 3 loves to make you do, it is to click on things. Remember the chests and lockers in previous games, and how they could sometimes be a pain to open? Fortunately, there weren’t too many of them. This game, on the other hand, has more points of interest in an empty forest than the average city sector did before. There will be herbs to gather in the wilderness providing medicine, mechanical salvage anywhere with houses or vehicles providing Parts, and hackable items in the form of radios or phones, providing either money or intel for nearby sectors. How one goes about hacking a rotary phone for cash I do not know, but Jagged Alliance 3 makes you do it over, and over, and over again. This is in addition to containers of loot, which are equally numerous. I would estimate that on average, each sector has in abundance of 20 such spots of interest. A lot of these are very small and/or hidden by the camera, making you have to zoom in and rotate the camera just right in order to make your mouse click register properly. Too often, also, the selected characters will simply run over to the object and stand there, not only making you click again but also forcing you to move your mercs out of the way again first. To make matters worse, these points of interest are not revealed until a mercenary is nearby, meaning that to get all the loot, you will need to zigzag across the entire sector. Then there are locked or trapped containers, which will require additional clicking as you select the merc with the highest skill to unlock or disarm the mechanism, and then more clicking to finally open it.

This may seem like severe nitpicking, but the fact is that you will spend so much time doing this that it takes a genuine toll on enjoyment. The rush of a completed battle will always be tempered by the prospect of having to spend time clicking, clicking, clicking around the entire sector to gather the fruits of your murder. There is a convenient menu accessible from the strategic view to examine and pick up all the loot in a sector, but naturally this does not include herbs, mechanical salvage, hackable objects, or loot in unopened containers, so it barely helps at all.

You might ask, if this is such a chore, why do it? Well, unless you are extremely careful (see: savescumming), your mercs will frequently be injured, and healing them up costs a lot of medicine. You will rarely have a comfortable stock, and even if you do, one or two battles going sideways will more or less deplete it. The same goes for parts. While repairing weapons costs nothing but time, weapon modifications as well as crafting ammunition and explosives have exorbitant costs. On the face of it, this is a good thing – scarcity makes for more compelling gameplay, after all – but when the remedy is so banal, you will find yourself wishing that meds and parts were as irrelevant as money. Moreover, loot from containers is, well, loot, and in such an equipment-centric game you will not want to skip what could be a character-defining piece of kit. Put simply, if you choose not to engage in the soul-crushing clicking, you will be putting yourself at a significant disadvantage. It is extremely frustrating.

This brings us to the inventory. Inventory management has never been a particularly big part of the series (if one discounts the 1.13 mod for Jagged Alliance 2, which cranks it up to 11). Nor, on the face of it, is it here. Each mercenary gets a number of inventory slots corresponding to their strength score. All items except bulkier weapons take up one slot each. In other words, nothing very exciting for the inventory-managing enthusiast, nor anything very different from the rest of the series. It’s arguably the simplest it’s ever been. There is one significant departure from tradition, however: all ammunition, in addition to meds and parts, is stored in a separate, shared inventory, unlimited in size. This means that mercs no longer need to carry clips with them, and will only run out of ammunition if there is none left in the shared store.

Though at first it appears a mystery why the developers have chosen this approach in a game with otherwise reasonably complex systems (and which has also proven in abundance that it’s not shy of making the player engage in busywork), it seems likely that this was considered a necessary evil. You will pick up so much random crap, in the form of weapon modifications, non-cash valuables, twenty flavours of grenades, situationally useful gear like gas masks and night vision goggles, as well as lots and lots of quest items, that to add ammo into the mix would seem to tax the rudimentary inventory system beyond its limits. It is clear that the aim behind simplifying the way ammunition is handled was to cut down on inventory management. The thing is, I’m not sure why they bothered, since the inventory management is terrible anyway. There’s simply too much stuff, and if the developers wanted to make the inventory as unobtrusive as possible they should have either made each merc’s personal inventory bigger, or offloaded all the other stuff to a shared inventory rather than the ammunition. What we’ve been given is a compromise that won’t please anybody.

A lot of the problems mentioned in this section would appear to stem from the idea that the player is supposed to live off the land. As mentioned, the opportunities to buy or sell equipment are very limited, and you will mostly have to rely on what you can scrounge for yourself. However, the developers clearly weren’t able to think of ways to reconcile this idea with the equipment and utility item porn that the series has become known for, as well as the increased focus on non-combat activities, without creating a lot of mindless drudgery in the process.

Conclusion

What do we have here, then? At its core, we have a game that takes the Jagged Alliance formula, tries to replicate it faithfully, and largely succeeds. For every new feature it introduces to the series, there are two others that work more or less the same as they did in 1999. You will have noticed that a lot of the text in this review is devoted to the game’s faults. The reason for that is that most of its strengths can simply be summed up as: it’s like Jagged Alliance 2. That doesn’t take up a lot of screen space, but it is a big deal. It may sound negative to conclude that the parts that make this game good are the parts that Haemimont Studios stole from the game they were making a sequel to, while the wonky parts are the things they came up with themselves, but that’s mostly how it is. The new stuff ranges from decent to completely idiotic. The much expanded dialogue, quest, and character development systems are competently made, and take the series in a new direction – whether you’ll like them or hate them depends on your taste for such things. Meanwhile, everything having to do with how combat starts reeks of efforts to minimise frustration by giving the player unfair advantages and then giving the enemies different unfair advantages to compensate, resulting in a big mess.

But that’s small potatoes. The fact is that when I finished the game, I immediately started a second playthrough, not for reviewing purposes but because I was having so much fun. I then finished my second playthrough without having to take a break, which is something I very rarely do in a game. Simply put, Jagged Alliance 3 is the worst true entry in the series, but it is that: a true new entry in the series. It may not be the timeless classic we feel any sequel to Jagged Alliance 2 ought to be, as it’s dragged down by some truly baffling design decisions, wonky balance and a lot of horrible clicking, but it’s also the best game of its kind that we’ve had in twenty years.

If I were working for IGN, I would say that the game is too afraid to try new things, and hangs on to obsolete mechanics that don’t belong in the modern era. What I will say instead is that it gets the balance between old and new absolutely bang on, mostly respecting the old while not being afraid to try new things. Whether or not you will like the game depends entirely on how offensive you find the areas where the game tries new things and fails. There is a free demo available, so you can decide for yourself without spending a dime. I myself was sceptical at first, and while there is no denying the game’s flaws, I can safely say that Haemimont Studios won me over. If you like Jagged Alliance, give this a try.

Jagged Alliance 3 review

Not at all in the same way that Carlsberg is probably the best beer in the world, Jagged Alliance is probably the best turn-based tactics video game series in the world. It is a perfect blend of small-scale squad management, hilarious action-movie homages and excellent turn-based combat. Jagged Alliance 2 might be my favourite game of all time.

That’s precisely why my reaction when a new game was announced was: not this shit again. The Jagged Alliance games that have been released this century are best described in words not appropriate for a family-friendly magazine such as this. Suffice it to say that each of the studios that made them was forced to shutter its doors more or less immediately, in a rare example of karmic justice in the video game industry.

This time, the live grenade was handed to Bulgarian outfit Haemimont Studios. But this time, it was not going to be a spinoff. This time it was going to be the real deal, in the form of a numbered entry. Marketing tricks aside, when news began to surface about the game, it became clear that this was indeed a more ambitious attempt at a true sequel than the drivel we’d been served for the past 20 years. They’d even snagged Ian Currie. It was at least worth a closer look.

The game takes place in the former French colony of Grand Chien, which has been taken over by a terrorist group called the Légion, led by a mysterious character known only as the Major. The Légion have kidnapped the president, and who better to save him than Laptop Guy and his private mercenary company of choice, the Association of International Mercenaries, A.I.M. for short.

As usual, saving the day is achieved through taking over the entire country by shooting a busload of enemies, while keeping the campaign running via careful budgeting. Like previous games in the series, Jagged Alliance 3 operates on two levels, blending strategy and RPG elements: the strategic view is used to command squads around the world map and engage in various automated operations, while the tactical view is used for fighting and chatting with NPCs.

Don’t Cry For Me Grand Chien

The strategic layer will be very familiar to those who have played Jagged Alliance 2, as it has been replicated almost exactly. The game world is divided into a square grid of sectors, and in true Chutes and Ladders fashion the game starts you off as far away from your goal as possible. The mercenaries at your disposal are grouped into squads, which you can move around from sector to sector in pausable real time. Most sectors have enemies in them, and once your mercs have cleared a sector of enemies, it’s considered to be under your control.

Different sectors provide different bonuses when conquered. The most important type of sector is the diamond mine, of which there are five in the game and which represent your only steady source of income. The amount of cash each mine generates is tied to the loyalty score of the nearest city, which can be raised by liberating city sectors, repelling enemy counterattacks, and doing favours for its inhabitants. Once a city sector is under your control, you can train militia which will protect the sector against enemy offensives. The reason you need cities and mines is that mercenaries don’t work for free; they will need to be paid on a regular basis, and if you can’t afford their salaries they’ll pack their things and leave.

The main thrust of a standard campaign is to traverse the country sector by sector, clearing cities and mines and establishing your own troops to protect them, as you slowly paint the map blue. In addition to training militia, you can have your mercenaries train each other, bandage their wounds, and repair their gear. If this all sounds familiar, it’s because not a thing has changed about this dynamic since the previous game. It’s even still the case that militia can only be trained so much by mercenaries, with further advancement only possible through combat, and that mines will eventually run dry after a period (now this will happen to every mine, rather than just one).

Having said this, there are a few minor additions to the formula. The country of Grand Chien is not a single landmass, and as such, not all travel can be done on foot. There are now port sectors, which allow your mercs to take boat rides to any water-adjacent sector. Unfortunately, ports aren’t as strategically important as they sound. They don’t as a rule function as city sectors, so training militia for them is not possible, and the enemy will not station troops in them or send attack squads after them. The whole system ends up being barely an inconvenience, and the usual approach of clicking on whichever sector you want to travel to works the same whether the destination is accessible by road or sea. Taking a boat costs money, but this too is negligible.

A more interesting addition is outpost sectors. These are usually heavily guarded, and when under enemy control periodically generate attack squads which are sent out to retake nearby player-controlled sectors. They are prime targets for both the player and the enemy, and will provide some of the most challenging battles outside of set-piece events, especially if you happen to go in at a time when it’s full of fresh attack squads. Also roaming around the map are diamond shipments generated by region-controlled mines and heading out of the country. These can be intercepted for a significant cash prize. While you would by no means call Jagged Alliance 3 a deep strategic simulation, these additions are a welcome step towards making the world feel more dynamic as compared to its predecessors. The implementation of enemy designated attack squads also facilitates the execution of a certain major plot event in a very pleasing fashion, by having stuff actually happen in a systemic way rather than simply flipping script switches.

It is a shame that the experience is marred by an abysmal UI. While the UI for the combat view is functional enough, the strategic UI is a mess of submenus and lack of clarity. If you’ve played Jagged Alliance 2, you will recall that all mercenaries under your employ will be shown on the same page, and assigning them tasks and moving them about was as simple as two mouse clicks. Here, you will need to navigate a submenu called Operations, where you can assign tasks on a per-squad basis. This menu is extremely unwieldy. For example, the repair operation lets you queue up items to be fixed, but this queue is extremely short, so to repair all your gear you will often need to start the repairing operation several times as the mercs finish the four items you’ve assigned them to. What’s more, mercs will only repair gear in their squad’s possession, which means that if you happen to have multiple squads in the same sector, the second squad will need to drop their gear if they want it repaired. As for travelling, you cannot change the route mid-travel. You will first need to cancel travel, wait as the mercs make their way to the centre of the nearest sector, then resume with the updated route. While you’re doing this, other operations continue and may be completed while you’re fiddling, pausing the game constantly as you wonder why nothing’s happening. You can't tell at a glance how many militiamen there are in a sector, or even where your own squads are. The time progression has only one speed, which is sometimes too fast and sometimes awfully slow. In general, every single action has been made to require a few more mouse clicks and just a little more hassle as compared to the previous game, while the actual functionality hasn’t changed at all.

Another issue with the strategic part of the game is money. You start off with a little bit of cash, which is enough to hire a couple of the less expensive mercenaries for a couple of weeks. But eventually their contracts will run out, and you’ll also want to hire more bodies, which means that one of your primary objectives at the start of the game will be to generate income. It's a good system that keeps you from dawdling, at least in theory. And in the early parts of the game money can indeed be tight, especially if you’ve hired some of the more expensive mercs, or if you’re forced to spend significant time resting and healing your squad. However, this very quickly stops being a concern. The issue is very simple: mines generate too much money. If you’ve taken over two of the five mines in Grand Chien, you’re essentially set for life, and there’s no real reason to pursue the other ones, at least until one of yours runs dry.

That’s half the reason why money is so abundant. The other half is that there’s really nothing to spend it on. There is no Bobby Ray’s or a Micky O’Brien in this game, on whom you could unload some of your cash in exchange for weapons and other items; your only real expense will be mercenary contracts, and that’s not enough. Even if you invest in several squads and fill them up with the most expensive mercenaries you will not have to worry. To be sure, you could buy yourself quite a bit of leeway in the previous games as well, but it was never as easy as it is here. Presumably, mine income is something that can be tuned very easily, so by the time you read this there may well be a patch or a mod that improves things. As it is, the balance is off.

Tacticulations

You’ll spend a lot of time juggling operations in the strategic view, but the real meat of the game takes place in the tactical view, where you control each individual mercenary in turn-based combat. This is where Jagged Alliance made a name for itself, and where any sequel absolutely needs to deliver.

And what do you know – it does. The game once again copies a number of its systems from Jagged Alliance 2, and since that is probably the pinnacle of the genre, as you’d expect it all works very nicely. The control you have over your mercenaries is very granular, and you can specify everything from whether they should be running, crouching or lying down, to exactly how many action points they should spend zeroing in on an enemy, as well as what part of the body to aim for. Unconventionally (though not for the franchise), chance to hit is not displayed, and you will have to eyeball each shot, while mercs provide helpful comments whenever they think a shot is likely to succeed or fail. It’s a great system, which strikes a good balance between uncertainty and feedback, and it’s nice to see it make its return.

There are other such nuances to the combat as well, which are not new to the series but are rarely seen elsewhere, especially these days. With the option to target body parts comes location-specific damage; so a shot to the leg will decrease movement, a shot to the arms will decrease accuracy, and so on. Guns fire bullets with real trajectories and real penetration, which means that a missed shot might hit something else, or a shot with a high-penetration weapon might travel right through the target and hit something else behind him. Cover can be destroyed, visual contact can be broken with smoke, characters can be suppressed by gunfire and flashbangs, and combatants can get panicked and lose their turn entirely.

Energy and morale are also in, although the energy and morale metres of the previous game have been replaced by a ladder of cumulative status effects. If forced to operate for a long time without a break, mercs will gain the “Tired” status, reducing their maximum action points by 1. If forced to keep going, they will eventually become “Exhausted”, losing another action point. On top of that, exhausted characters are liable to fall unconscious if they’re hit with more energy-draining attacks. Likewise with morale: it can drop to low or very low, decreasing AP, if mercs take significant damage or if someone dies, and rise when mercs score good kills, complete quests or progress in the campaign. Overall, the effect works out to be about the same as in the previous game, if presented in a slightly more cumbersome way.

One aspect of combat that deserves particular praise is the level of environmental destruction the game supports. You can break a lot of scenery in Jagged Alliance 3. Certain things you will not be able to blow up, such as the skeletons of larger buildings as well as bridges and other things essential to the traversability of the map. Still, the level of damage that you can do to most structures is impressive and a delight to play with. Level the second floor of a building with a rocket launcher, and have enemies rain down from above into the waiting arms of your knife-wielding melee specialist on the first floor. Blow the roof off a building with a grenade, then chuck a second one through the hole into the cluster of enemies huddled inside. It is simply great fun, and makes explosives specialists very valuable additions to your team, quite apart from their direct damage potential. There are plenty of sector designs that provide good opportunities to make use of their potential, too. It doesn’t reach the level of mayhem that you can cause in X-COM: Apocalypse or Silent Storm – the kings of the genre if all you want to do is raze the entire map – but it’s miles above most of the competition.

A little more on sectors: they are no longer uniformly sized, which means that unimportant sectors, not belonging to a city nor offering any special services, can often be quite small. Other sectors, particularly important ones like military bases, are much bigger – bigger indeed than in any of the previous games. Sectors are also quite varied, with everything from featureless savannah to urban streets and fortified military complexes. Additionally, the transition to fully-3D environments means multi-story buildings, guard towers, and natural elevation which serves to further distinguish sectors. There is also a day and night cycle as well as a weather system, which can affect combat in different ways – night reduces vision range, rain muffles noise, and so on. All in all, the variety is excellent, and no two important sectors feel the same.

It all adds up into a very enjoyable combat system which feels and controls like Jagged Alliance 2 in more ways than not. It is particularly good in bigger, more protracted encounters as the fighting settles into a rhythm. Injured characters can’t be healed instantly, as taking significant damage causes wounds which decrease maximum HP – though, disappointingly, don’t have an impact on AP and won’t start bleeding like they used to do. It nevertheless means that keeping a wounded merc in the fight is a risky proposition, and you will want to prioritise retreating with those while calling in others to bandage them, as the rest hold the line against enemies. The combat is generally a little too easy even on the hardest difficulty, so these situations will be rarer than they should; when they happen, though, they’re a perfect example of what makes combat in these games so compelling.

However, not all is roses. Alongside all the good stuff, there is a set of problems which drags the experience down significantly. One of these is how turn interruptions are handled. The series, up until now, has allowed each combatant to save up unspent action points from his team’s turn, giving him the chance to interrupt the opponents’ turn and use his remaining AP for whatever. Jagged Alliance 3 instead implements an overwatch system. Characters can now use their unspent AP to specify an overwatch area, and will then open fire on any enemy who enters it.