RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Arnold Hendrick on Darklands (with Retrospective by Josh Sawyer)

RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Arnold Hendrick on Darklands (with Retrospective by Josh Sawyer)

Codex Interview - posted by Crooked Bee on Wed 13 June 2012, 12:46:52

Tags: Arnold Hendrick; Darklands; Josh Sawyer; MicroProse; Retrospective InterviewDarklands, released by Microprose in 1992, is a party-based "sandbox" computer role-playing game set in the Holy Roman Empire during the 15th century, and one of the most important titles in the history of the genre. In today's installment of our RPG Codex Retrospective Interview series, we present you with an interview with Lead Designer on Darklands, Arnold Hendrick himself, as well as a retrospective on Darklands written by our guest contributor, Obsidian Entertainment's Josh Sawyer, Lead Designer on Icewind Dale II, Neverwinter Nights 2 and Fallout: New Vegas, who also kindly agreed to serve as a guest co-interviewer, Darklands being, as he writes in the article, "one of the CRPGs closest to my heart." Have a snippet from Josh Sawyer's retrospective:

As well as from the interview with Arnold Hendrick:

I strongly suggest you read the interview in full: RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Arnold Hendrick on Darklands (with Retrospective by Josh Sawyer)

We are grateful to Arnold and Josh for their time! Special thanks are also due to Jaesun, Monolith and Zed for their feedback and suggestions.

The Magic Candle was the most unusual CRPG I had played to that point, but I wasn't prepared for Darklands. It used 15th century history for almost everything: canonical hours, Medieval currency, alchemical formulae, Catholic saints, practical arms and armor of the era, period-accurate names and spellings for cities, traditional music, mythic conceptions of satanic Templars – the works.

It also bucked so many CRPG conventions that it took me a while to wrap my head around it. Instead of making a party of characters of different races and classes, you developed them along life paths, Traveller-style, in five year increments. You could, in fact, have a party with a grizzled knight, a young bandit, a hapless mystic of affective piety, and an 80 year-old alchemist (whom you most certainly would not abandon for his potent potions five minutes into gameplay!) And as previously mentioned, there were no alignments, no levels, no experience points – just a learn-by-doing skill system and a big open world. I felt like the game gave me the freedom to explore “Greater Germany” as I saw fit.

Not that it was a forgiving exploration. Darklands was a wonderful open world game, one that rarely warned travelers about dangers lurking in a Raubritter's castle or what you might encounter while stumbling through the Black Forest. You could find yourself arguing with a demon in Latin at the Devil's Bridge, fleeing from the Wild Hunt after you've interrupted the witches' High Sabbath, or praying for a saint's intercession as you await public execution in a town square.

It also bucked so many CRPG conventions that it took me a while to wrap my head around it. Instead of making a party of characters of different races and classes, you developed them along life paths, Traveller-style, in five year increments. You could, in fact, have a party with a grizzled knight, a young bandit, a hapless mystic of affective piety, and an 80 year-old alchemist (whom you most certainly would not abandon for his potent potions five minutes into gameplay!) And as previously mentioned, there were no alignments, no levels, no experience points – just a learn-by-doing skill system and a big open world. I felt like the game gave me the freedom to explore “Greater Germany” as I saw fit.

Not that it was a forgiving exploration. Darklands was a wonderful open world game, one that rarely warned travelers about dangers lurking in a Raubritter's castle or what you might encounter while stumbling through the Black Forest. You could find yourself arguing with a demon in Latin at the Devil's Bridge, fleeing from the Wild Hunt after you've interrupted the witches' High Sabbath, or praying for a saint's intercession as you await public execution in a town square.

As well as from the interview with Arnold Hendrick:

Josh Sawyer: Your background is in military history, but there's a fair amount of social history in Darklands. When you set out to design Darklands, did you always intend for it to be set in the 15th century Holy Roman Empire, or did you consider other times and places? What about the setting most appealed to you?

You’re correct, my academic training is in history, and my specialty is military history. However, any decent military historian should be aware of the social, political and economic issues surrounding warfare. At the very start, I wanted the Darklands' “hook” to be that it would be use some beliefs from the era to “justify” fantastical elements, rather than trotting out the usual bog-standard wizards, clerics, bards, etc. Where possible, I like my game designs to provide an insight into history – a “you are there” feel. When searching for tactical tradeoffs and interesting details, why goof around conjuring up stuff when there is plenty of interesting historical material to use?

I was also aware that no RPG set in a pre-medieval era had been successful. This meant the earliest conceivable period was the Dark Ages after the fall of western Rome. Given how risky the project already was, I decided the time period had to include some things familiar to fantasy gamers. This included all types of armor up to and including full plate. This in turn meant a full panoply of weaponry, from swords, axes, maces and bows, to hammers, bills, halberds, crossbows and longbows. This virtually required the game to be set in the late 1300s to 1400s.

If the game were set in France or Britain, it would inevitably be drawn into the events of the Hundred Years War (1330s to 1440s), on which I lacked sufficiently detailed material at that time. Germany’s chaotic “robber knight” (raubritter) era became an obvious choice, especially since the very chaos of the period gave me consider “historical license.”

RPG Codex: You probably had a lot of plans and ideas for a possible sequel to Darklands that had to be left unrealized, or at least a lot of ideas that did not make it into the game due to time and resource constraints. What were some of the things that had to be cut or that you planned for a sequel?

A true sandbox game would have more quests and activities than the characters could perform in any normal lifetime! I had originally hoped to have many quest storylines, not just one apocalyptic one. However, that was impractical given the growing time and cost. If the game had become an instant smash hit, then we could have done sequels with more storylines.

There is a lot more you can do with German history in that period. You can also add in things about the Hussites in Bohemia, the power of the Hanseatic League, the fall of the Teutonic Order, and rising Polish kingdom under the great Jagiellon dynasty. Adventures involving the struggle between the various papal factions could have been very interesting: the catholic church had three competing popes in the early 1400s.

Meanwhile, starting the late ‘90s, Jonathan Sumption has been slowing putting out an absolutely incredible multi-volume historyof the Hundred Years War. It is one of those seminal works that will be the defining history of the period for decades to come, much like S.E.Morison’s history of US Naval Operations in WWII or Oman’s history of the Peninsular wars. Armed with Sumption’s work, some great RPGs set in the Hundred Years War period are now possible.

You’re correct, my academic training is in history, and my specialty is military history. However, any decent military historian should be aware of the social, political and economic issues surrounding warfare. At the very start, I wanted the Darklands' “hook” to be that it would be use some beliefs from the era to “justify” fantastical elements, rather than trotting out the usual bog-standard wizards, clerics, bards, etc. Where possible, I like my game designs to provide an insight into history – a “you are there” feel. When searching for tactical tradeoffs and interesting details, why goof around conjuring up stuff when there is plenty of interesting historical material to use?

I was also aware that no RPG set in a pre-medieval era had been successful. This meant the earliest conceivable period was the Dark Ages after the fall of western Rome. Given how risky the project already was, I decided the time period had to include some things familiar to fantasy gamers. This included all types of armor up to and including full plate. This in turn meant a full panoply of weaponry, from swords, axes, maces and bows, to hammers, bills, halberds, crossbows and longbows. This virtually required the game to be set in the late 1300s to 1400s.

If the game were set in France or Britain, it would inevitably be drawn into the events of the Hundred Years War (1330s to 1440s), on which I lacked sufficiently detailed material at that time. Germany’s chaotic “robber knight” (raubritter) era became an obvious choice, especially since the very chaos of the period gave me consider “historical license.”

RPG Codex: You probably had a lot of plans and ideas for a possible sequel to Darklands that had to be left unrealized, or at least a lot of ideas that did not make it into the game due to time and resource constraints. What were some of the things that had to be cut or that you planned for a sequel?

A true sandbox game would have more quests and activities than the characters could perform in any normal lifetime! I had originally hoped to have many quest storylines, not just one apocalyptic one. However, that was impractical given the growing time and cost. If the game had become an instant smash hit, then we could have done sequels with more storylines.

There is a lot more you can do with German history in that period. You can also add in things about the Hussites in Bohemia, the power of the Hanseatic League, the fall of the Teutonic Order, and rising Polish kingdom under the great Jagiellon dynasty. Adventures involving the struggle between the various papal factions could have been very interesting: the catholic church had three competing popes in the early 1400s.

Meanwhile, starting the late ‘90s, Jonathan Sumption has been slowing putting out an absolutely incredible multi-volume historyof the Hundred Years War. It is one of those seminal works that will be the defining history of the period for decades to come, much like S.E.Morison’s history of US Naval Operations in WWII or Oman’s history of the Peninsular wars. Armed with Sumption’s work, some great RPGs set in the Hundred Years War period are now possible.

I strongly suggest you read the interview in full: RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Arnold Hendrick on Darklands (with Retrospective by Josh Sawyer)

We are grateful to Arnold and Josh for their time! Special thanks are also due to Jaesun, Monolith and Zed for their feedback and suggestions.

RPG Codex Retrospective Interviews is a series that grew out of our fascination with the rich history of computer role-playing games. It focuses on developers and individual titles that made a unique or significant contribution to the genre, aiming to cover a developer's career and approach to RPG design or, respectively, the most relevant aspects of the game in question and the design philosophy behind it.

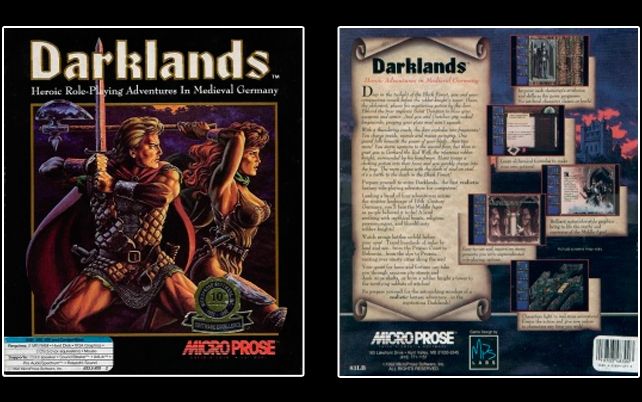

Darklands, released by Microprose in 1992, is a party-based "sandbox" computer role-playing game set in the Holy Roman Empire during the 15th century, and one of the most important titles in the history of the genre. The player visits real historical locations, encounters creatures that inhabitants of Europe believed in at the time, prays to Catholic saints to trigger certain events, and brews alchemical potions instead of casting spells the traditional way. Darklands' sheer ambition and scope, meticulously researched historical background, freedom of exploration, unorthodox skill-based character development system, and unique text-based interface for quests make it immediately stand out among other CRPGs even to this day.

Today we present you with an interview with Lead Designer on Darklands, Arnold Hendrick himself, as well as a retrospective on Darklands written by our guest contributor, Obsidian Entertainment's Josh Sawyer, Lead Designer on Icewind Dale II, Neverwinter Nights 2 and Fallout: New Vegas, who also kindly agreed to serve as a guest co-interviewer, Darklands being, as he writes below, "one of the CRPGs closest to my heart."

A Darklands Retrospective

by Joshua E. Sawyer

Darklands Interview with Arnold Hendrick, Lead Designer

RPG Codex: Before you started developing computer games, you had been involved with a number of board games, such as Trireme (1980), Barbarian Prince (1981), Star Viking (1981) and Grav Armor (1982). How did you move on to video games?

RPG Codex: How did it happen that you got hired by Microprose, and what was the atmosphere and company culture like at Microprose when you worked there?

RPG Codex: Can you give us a rundown of the things you have been involved with since Microprose closed and what you are up to these days?

RPG Codex: Before Darklands, you designed a number of simulation and strategy games for Microprose, such as Gunship (1986), Red Storm Rising (1988), M1 Tank Platoon (1989) and Silent Service II (1990), and you are also co-credited for the original design of Sid Meier's Pirates! (1987). What were your goals with these games, and how did your work on them influence the way you approached Darklands?

RPG Codex: Darklands immediately stands out as the only CRPG among your Microprose titles. Why did you decide the game had to be a role-playing and not a strategy or action game? Did you look to other role-playing games (computer or pen and paper) for inspiration?

Josh Sawyer: Your background is in military history, but there's a fair amount of social history in Darklands. When you set out to design Darklands, did you always intend for it to be set in the 15th century Holy Roman Empire, or did you consider other times and places? What about the setting most appealed to you?

Josh Sawyer: Darklands features a number of mechanics that were unusual for CRPGs of the time, most notably the lack of classes, levels, and experience points. What were your motivations and goals when you were designing the character mechanics?

Josh Sawyer: Historical games like Darklands go "hard" on accurate detail, with those details often driving mechanical concepts. How do you approach balancing historical accuracy with good gameplay if they are in conflict?

Josh Sawyer: Darklands presents a mythic version of Europe in which the allegations of King Philip IV of France against the Knights Templar are true: many Templars are full-fledged Satanists taking orders from a demon called Baphomet. Additionally, the world view of later writers like Kramer and Sprenger and Jean Bodin, in which witches lurk around every corner, was presented reality in Darklands' Greater Germany. Did you have any concerns about portraying these elements of historical slander and hysteria as part of the game?

Josh Sawyer: In your interview on Matt Chat, you discussed the lack of reaction from Catholics about the portrayal of the Catholic Church in Darklands. Though many officials of the church in the game were presented in a negative light, being a "good Catholic" (learning about and praying to saints, opposing evil) was mechanically the most advantageous way to play the game (and the only way the story works out). Do you think this may have influenced players' perceptions?

RPG Codex: Darklands' combat is real-time with pause, an unorthodox thing for a CRPG at the time. Why did you choose to go for this kind of combat gameplay? Would not party-based historical simulation rather call for turn-based as the more tactical kind of combat?

Josh Sawyer: Darklands features an interesting blend of menu-driven gameplay, world map exploration, and small-scale combat maps. You've previously discussed that the game was initially conceived as having a lot of combat, but that you had other plans in mind as well. How were these other features conceived and developed?

RPG Codex: What were the main challenges involved in designing a "sandbox" CRPG of Darklands' proportions, from both a managerial and design standpoint?

RPG Codex: You probably had a lot of plans and ideas for a possible sequel to Darklands that had to be left unrealized, or at least a lot of ideas that did not make it into the game due to time and resource constraints. What were some of the things that had to be cut or that you planned for a sequel?

RPG Codex: What, in your view, has changed about video game, and in particular CRPG, design today compared to the time you were designing Darklands? Are there certain design trends that are worrisome to you or, on the contrary, that you especially appreciate?

RPG Codex: In a past interview, you said Microprose's downfall had to do with the way designers who worked there were only thinking about the games they wanted to make and not about the budget or people power required. Microprose, like many others at the time, was mainly about gaming, not business, and the business aspect suffered because of that. Would you agree that today we seem to have the opposite, "business first, gaming second" kind of situation, and what is your stance on that?

RPG Codex: Given the recent Kickstarter success stories of Tim Schafer and Brian Fargo, what do you think of crowdfunding as a way of independent video game publishing and would you consider turning to Kickstarter to fund a sequel or a spiritual successor to Darklands? Ideally, if given enough time and resources, how would you go about creating a game like Darklands today?

RPG Codex: Thank you for your time!

We thank J.E. Sawyer for contributing to the interview and writing up the retrospective. Thanks are also due to Jaesun, Monolith and Zed for their feedback and suggestions.

Darklands, released by Microprose in 1992, is a party-based "sandbox" computer role-playing game set in the Holy Roman Empire during the 15th century, and one of the most important titles in the history of the genre. The player visits real historical locations, encounters creatures that inhabitants of Europe believed in at the time, prays to Catholic saints to trigger certain events, and brews alchemical potions instead of casting spells the traditional way. Darklands' sheer ambition and scope, meticulously researched historical background, freedom of exploration, unorthodox skill-based character development system, and unique text-based interface for quests make it immediately stand out among other CRPGs even to this day.

Today we present you with an interview with Lead Designer on Darklands, Arnold Hendrick himself, as well as a retrospective on Darklands written by our guest contributor, Obsidian Entertainment's Josh Sawyer, Lead Designer on Icewind Dale II, Neverwinter Nights 2 and Fallout: New Vegas, who also kindly agreed to serve as a guest co-interviewer, Darklands being, as he writes below, "one of the CRPGs closest to my heart."

A Darklands Retrospective

by Joshua E. Sawyer

Last year, I took a wandering tour through Germany to visit the village in Ostallgäu where my grandmother was born. Along the way, I played Darklands on the train for old time's sake. I wanted my party in the game to adventure in the historical locations that matched my current travels.* The experience reminded me of all of the positive ways it had influenced me: personally, academically, and in how I think about game design.

By the time I was a sophomore in high school, I had already played a lot of CRPGs, starting with Bard's Tale and hitting full stride with SSI's “Gold Box” D&D games. I'd seen a variety of settings and styles of games, all sorts of systems and mechanics. I figured I “got” CRPGs reasonably well. When my friend, Tony, told me about Darklands, I wasn't quite sure what to make of it. I remember the conversation going something like this:

“So it's historical... and everyone's human?”

“Yeah.”

“And there's no classes, no alignment... ?”

“No levels, no experience points. You raise most of your skills just by using them. Your characters can die of old age.”

“...?”

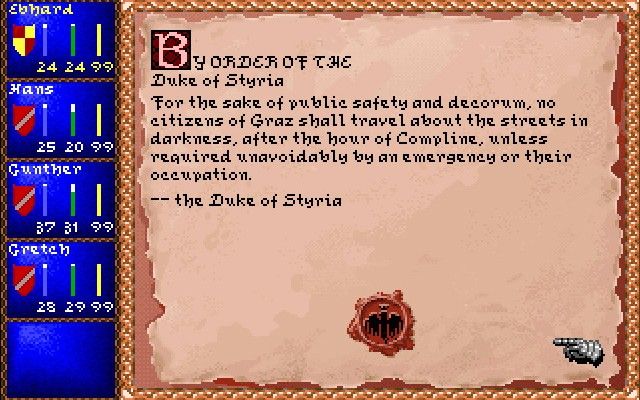

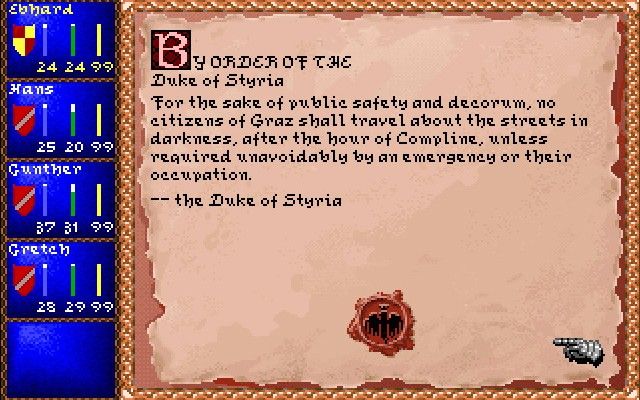

The Magic Candle was the most unusual CRPG I had played to that point, but I wasn't prepared for Darklands. It used 15th century history for almost everything: canonical hours, Medieval currency, alchemical formulae, Catholic saints, practical arms and armor of the era, period-accurate names and spellings for cities, traditional music, mythic conceptions of satanic Templars – the works.

It also bucked so many CRPG conventions that it took me a while to wrap my head around it. Instead of making a party of characters of different races and classes, you developed them along life paths, Traveller-style, in five year increments. You could, in fact, have a party with a grizzled knight, a young bandit, a hapless mystic of affective piety, and an 80 year-old alchemist (whom you most certainly would not abandon for his potent potions five minutes into gameplay!) And as previously mentioned, there were no alignments, no levels, no experience points – just a learn-by-doing skill system and a big open world. I felt like the game gave me the freedom to explore “Greater Germany” as I saw fit.

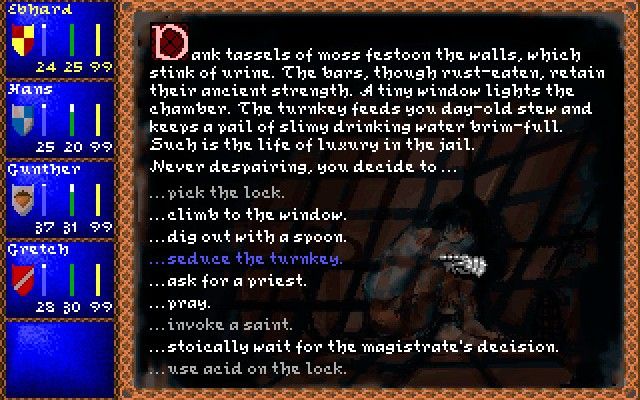

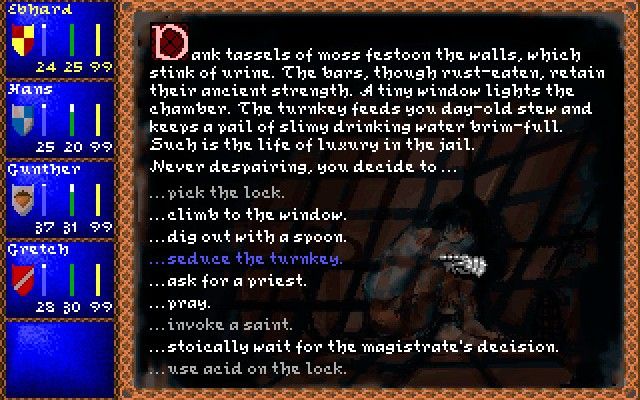

Not that it was a forgiving exploration. Darklands was a wonderful open world game, one that rarely warned travelers about dangers lurking in a Raubritter's castle or what you might encounter while stumbling through the Black Forest. You could find yourself arguing with a demon in Latin at the Devil's Bridge, fleeing from the Wild Hunt after you've interrupted the witches' High Sabbath, or praying for a saint's intercession as you await public execution in a town square.

Darklands created a fantastic world out of the “mundane” myths of historical Europe. It developed an equivalent of “Radiant Story”-style quests almost twenty years before Skyrim, and it had a real-time with pause combat system six years before Baldur's Gate. Most importantly, it gave players like me a new way to think about what CRPGs could be and a greater appreciation for all of the fantastic things we can find in history books. For those reasons, it will always be one of the CRPGs closest to my heart.

* Last year's party didn't quite made it to München before I flew home, but I'm sure they'll get there before the alchemist keels over.

By the time I was a sophomore in high school, I had already played a lot of CRPGs, starting with Bard's Tale and hitting full stride with SSI's “Gold Box” D&D games. I'd seen a variety of settings and styles of games, all sorts of systems and mechanics. I figured I “got” CRPGs reasonably well. When my friend, Tony, told me about Darklands, I wasn't quite sure what to make of it. I remember the conversation going something like this:

“So it's historical... and everyone's human?”

“Yeah.”

“And there's no classes, no alignment... ?”

“No levels, no experience points. You raise most of your skills just by using them. Your characters can die of old age.”

“...?”

The Magic Candle was the most unusual CRPG I had played to that point, but I wasn't prepared for Darklands. It used 15th century history for almost everything: canonical hours, Medieval currency, alchemical formulae, Catholic saints, practical arms and armor of the era, period-accurate names and spellings for cities, traditional music, mythic conceptions of satanic Templars – the works.

It also bucked so many CRPG conventions that it took me a while to wrap my head around it. Instead of making a party of characters of different races and classes, you developed them along life paths, Traveller-style, in five year increments. You could, in fact, have a party with a grizzled knight, a young bandit, a hapless mystic of affective piety, and an 80 year-old alchemist (whom you most certainly would not abandon for his potent potions five minutes into gameplay!) And as previously mentioned, there were no alignments, no levels, no experience points – just a learn-by-doing skill system and a big open world. I felt like the game gave me the freedom to explore “Greater Germany” as I saw fit.

Not that it was a forgiving exploration. Darklands was a wonderful open world game, one that rarely warned travelers about dangers lurking in a Raubritter's castle or what you might encounter while stumbling through the Black Forest. You could find yourself arguing with a demon in Latin at the Devil's Bridge, fleeing from the Wild Hunt after you've interrupted the witches' High Sabbath, or praying for a saint's intercession as you await public execution in a town square.

Darklands created a fantastic world out of the “mundane” myths of historical Europe. It developed an equivalent of “Radiant Story”-style quests almost twenty years before Skyrim, and it had a real-time with pause combat system six years before Baldur's Gate. Most importantly, it gave players like me a new way to think about what CRPGs could be and a greater appreciation for all of the fantastic things we can find in history books. For those reasons, it will always be one of the CRPGs closest to my heart.

* Last year's party didn't quite made it to München before I flew home, but I'm sure they'll get there before the alchemist keels over.

Darklands Interview with Arnold Hendrick, Lead Designer

RPG Codex: Before you started developing computer games, you had been involved with a number of board games, such as Trireme (1980), Barbarian Prince (1981), Star Viking (1981) and Grav Armor (1982). How did you move on to video games?

I was at Heritage, a boardgame and miniatures company, as publishing director from 1979 to its demise at the end of 1982. In the process I designed a variety of boardgames and miniatures rules, as well as producing games by others. When the opportunity to join Coleco (a first generation console games company) appeared a couple months later in 1983, I jumped at it. I’ve been in computer games every since.

RPG Codex: How did it happen that you got hired by Microprose, and what was the atmosphere and company culture like at Microprose when you worked there?

Coleco’s computer game business was destroyed by the great console game “glut” of 1984 (the same over-supply of games that killed Atari). In 1985 I was job hunting again. A former Coleco co-worker suggested I talk to MicroProse. I became the first non-programming designer at that company. Having prior design experience in paper games, as well as prior computer game design and development put me in a unique position. I ended up working with Sid Meier on a variety of titles, recruiting a growing design staff into the company, and generally helping MicroProse grow. Unfortunately, we lacked process. Nobody was teaching project management as a discipline, so the development process was poorly organized by AAA development standards today. I do suspect it resembled many social game developers a few years back (when many actively avoided hiring game industry veterans).

In our defense at MicroProse, we were learning how to make PC games as we went along, and in many parts of the microcomputer software industry budget overruns and schedule slips were common during the 1980s. Nobody really understood how much effort was involved. Many persistently underestimated the time and cost of any new project. On the plus side, MicroProse had a great bunch of people. Virtually everyone was honestly trying to do their best and work together.

In our defense at MicroProse, we were learning how to make PC games as we went along, and in many parts of the microcomputer software industry budget overruns and schedule slips were common during the 1980s. Nobody really understood how much effort was involved. Many persistently underestimated the time and cost of any new project. On the plus side, MicroProse had a great bunch of people. Virtually everyone was honestly trying to do their best and work together.

RPG Codex: Can you give us a rundown of the things you have been involved with since Microprose closed and what you are up to these days?

I left MicroProse in 1995, shortly after the merger with Spectrum Holobyte that removed Bill Stealey from the company. Sid Meier departed about a year later. From ‘95-‘98 I worked with Stealey at his new company in North Carolina. However, I had already been bitten by the online gaming bug. As a result, I joined Kesmai in 1998, one of the few significant MMO companies in the world at that time. I’ve been in MMOs ever since, generally as a senior producer, often with senior design duties as well. I’ve dabbled in virtual worlds, and most recently was senior member of “The Amazing Society” studio of Gazillion Entertainment. After the success of our first product, Marvel Superhero Squad Online, Gazillion decided to close the studio, so I’m once more job hunting!

RPG Codex: Before Darklands, you designed a number of simulation and strategy games for Microprose, such as Gunship (1986), Red Storm Rising (1988), M1 Tank Platoon (1989) and Silent Service II (1990), and you are also co-credited for the original design of Sid Meier's Pirates! (1987). What were your goals with these games, and how did your work on them influence the way you approached Darklands?

We approached every game at MicroProse as a fresh slate. Even a sequel like Silent Service II (a WWII submarine game) got a completely fresh game design. I and one of the senior programmers at MicroProse (Jim Synoski) had wanted MicroProse to do a fantasy RPG for quite a while. We pointed to the continuing success of Origin’s Ultima series, not to mention various other titles, as a business justification. Eventually Bill Stealey gave in and allowed us to start on a shoestring budget. His main love was military simulation games, which strongly influenced internal projects except those initiated by Sid Meier.

RPG Codex: Darklands immediately stands out as the only CRPG among your Microprose titles. Why did you decide the game had to be a role-playing and not a strategy or action game? Did you look to other role-playing games (computer or pen and paper) for inspiration?

From a design standpoint, I took all my knowledge and experience of paper RPGs, the most influential of which was Traveller (GDW’s original version) and RuneQuest (Chaosium’s original version). I was also familiar with AD&D (then in its second edition), and back at Heritage in 1982 had even acted as editor and developer for a very minor paper fantasy RPG (Swordbearer). I was keenly aware of the general design issues. Most of all, I was very taken by Games’ Workshop original Warhammer fantasy RPG, which was set in late medieval Germany. That game caused me to look into medieval German history somewhat before Darklands.

Josh Sawyer: Your background is in military history, but there's a fair amount of social history in Darklands. When you set out to design Darklands, did you always intend for it to be set in the 15th century Holy Roman Empire, or did you consider other times and places? What about the setting most appealed to you?

You’re correct, my academic training is in history, and my specialty is military history. However, any decent military historian should be aware of the social, political and economic issues surrounding warfare. At the very start, I wanted the Darklands' “hook” to be that it would be use some beliefs from the era to “justify” fantastical elements, rather than trotting out the usual bog-standard wizards, clerics, bards, etc. Where possible, I like my game designs to provide an insight into history – a “you are there” feel. When searching for tactical tradeoffs and interesting details, why goof around conjuring up stuff when there is plenty of interesting historical material to use?

I was also aware that no RPG set in a pre-medieval era had been successful. This meant the earliest conceivable period was the Dark Ages after the fall of western Rome. Given how risky the project already was, I decided the time period had to include some things familiar to fantasy gamers. This included all types of armor up to and including full plate. This in turn meant a full panoply of weaponry, from swords, axes, maces and bows, to hammers, bills, halberds, crossbows and longbows. This virtually required the game to be set in the late 1300s to 1400s.

If the game were set in France or Britain, it would inevitably be drawn into the events of the Hundred Years War (1330s to 1440s), on which I lacked sufficiently detailed material at that time. Germany’s chaotic “robber knight” (raubritter) era became an obvious choice, especially since the very chaos of the period gave me consider “historical license.”

I was also aware that no RPG set in a pre-medieval era had been successful. This meant the earliest conceivable period was the Dark Ages after the fall of western Rome. Given how risky the project already was, I decided the time period had to include some things familiar to fantasy gamers. This included all types of armor up to and including full plate. This in turn meant a full panoply of weaponry, from swords, axes, maces and bows, to hammers, bills, halberds, crossbows and longbows. This virtually required the game to be set in the late 1300s to 1400s.

If the game were set in France or Britain, it would inevitably be drawn into the events of the Hundred Years War (1330s to 1440s), on which I lacked sufficiently detailed material at that time. Germany’s chaotic “robber knight” (raubritter) era became an obvious choice, especially since the very chaos of the period gave me consider “historical license.”

Josh Sawyer: Darklands features a number of mechanics that were unusual for CRPGs of the time, most notably the lack of classes, levels, and experience points. What were your motivations and goals when you were designing the character mechanics?

As a designer, I like to give players choices. Choices mean trade-offs and hopefully replayability. Players need the ability to make different, equally valid choices and see very different things happen.

The character generation system with its various tradeoffs, was something I always wanted to try since I first played Traveller. I liked the skill-based advancement system in various D&D competitors. The Darklands system was the result. You could mix fighting abilities with alchemy or religion for a character, but I “rigged” the systems to insure that it was virtually impossible to be good at everything. As a result, the best party has people of varied skills and specialities. I felt that there was a great deal of “fun” in creating various characters, seeing how they did when teamed up with other interesting characters.

All this is quite different from the “game as telling a story” philosophy popular in the last decade. The difficulty with storytelling is that each step of the story requires custom art assets and often gameplay, which is not especially replayable afterwards. Just because its different doesn’t make it better or worse.

The character generation system with its various tradeoffs, was something I always wanted to try since I first played Traveller. I liked the skill-based advancement system in various D&D competitors. The Darklands system was the result. You could mix fighting abilities with alchemy or religion for a character, but I “rigged” the systems to insure that it was virtually impossible to be good at everything. As a result, the best party has people of varied skills and specialities. I felt that there was a great deal of “fun” in creating various characters, seeing how they did when teamed up with other interesting characters.

All this is quite different from the “game as telling a story” philosophy popular in the last decade. The difficulty with storytelling is that each step of the story requires custom art assets and often gameplay, which is not especially replayable afterwards. Just because its different doesn’t make it better or worse.

Josh Sawyer: Historical games like Darklands go "hard" on accurate detail, with those details often driving mechanical concepts. How do you approach balancing historical accuracy with good gameplay if they are in conflict?

Gameplay and entertainment must always win over history. Not many people will buy and play a dull, boring, unplayable mess, no matter how “realistic” it may be. Therefore, gameplay must come first. However, all the little details and choices within a game can be drawn from history information or interpretations. Obviously there is an art to this. Sometimes a designer is forced into a particular historical interpretation or portrayal simply because it works best for the game.

Josh Sawyer: Darklands presents a mythic version of Europe in which the allegations of King Philip IV of France against the Knights Templar are true: many Templars are full-fledged Satanists taking orders from a demon called Baphomet. Additionally, the world view of later writers like Kramer and Sprenger and Jean Bodin, in which witches lurk around every corner, was presented reality in Darklands' Greater Germany. Did you have any concerns about portraying these elements of historical slander and hysteria as part of the game?

This is a great example of my previous point. Since the wealth of the templars was split between the crown and the church, I believe the demise of the templars was primarily to enrich the coffers of the French king, who was not coincidentally short of cash at the time. However, the existence of powerful demonic forces behind the Templars fits the storyline (as well as appealing to Sandy “Call of Cthulhu” Petersen, who wrote some of the bigger quests and storylines). Nevertheless, at least some commoners, lesser clergy and minor nobles believed the templars were guided by evil and/or satanic forces. If the game portrays the beliefs of SOME people in that period, it is remaining true to at least that most historical “accuracy.”

As for witchcraft hysteria, it definitely grew in the late 15th century into a massive horror in the 16th and 17th Centuries. The first major work about witches, Kramer & Sprenger’s Malleus Maleficarum, was published 1487. Scholarship strongly suggests that it did not spring from whole cloth. Modern historians have suggested that a few women may have encouraged such belief in witchcraft to give them some empowerment in a male dominated society. Personally, I prefer a broader view that fits witchraft persecutions and the Inquisition into reactions to a misogynistic larger pattern of social change. The centuries-old traditions of medieval society changed ever faster as greater trade, commerce, philosophical exchanges and increasing knowledge reshaped Europe.

As for witchcraft hysteria, it definitely grew in the late 15th century into a massive horror in the 16th and 17th Centuries. The first major work about witches, Kramer & Sprenger’s Malleus Maleficarum, was published 1487. Scholarship strongly suggests that it did not spring from whole cloth. Modern historians have suggested that a few women may have encouraged such belief in witchcraft to give them some empowerment in a male dominated society. Personally, I prefer a broader view that fits witchraft persecutions and the Inquisition into reactions to a misogynistic larger pattern of social change. The centuries-old traditions of medieval society changed ever faster as greater trade, commerce, philosophical exchanges and increasing knowledge reshaped Europe.

Josh Sawyer: In your interview on Matt Chat, you discussed the lack of reaction from Catholics about the portrayal of the Catholic Church in Darklands. Though many officials of the church in the game were presented in a negative light, being a "good Catholic" (learning about and praying to saints, opposing evil) was mechanically the most advantageous way to play the game (and the only way the story works out). Do you think this may have influenced players' perceptions?

Any game as complex as Darklands requires players capable of independent thought and judgment. Therefore, I can’t imagine any one computer game changing anyone’s religious views. I see nothing wrong with a game encouraging people to think about the role religion played in late medieval life. For example, the game allows the buying and selling of relics, something the modern Catholic church prohibits.

A interesting way to provide alternate views of an historical situation is a branching storyline. Alas, the piecemeal evolution of the game and the constant crush to get it done made it impossible to add this, much as I might have wished it.

A interesting way to provide alternate views of an historical situation is a branching storyline. Alas, the piecemeal evolution of the game and the constant crush to get it done made it impossible to add this, much as I might have wished it.

RPG Codex: Darklands' combat is real-time with pause, an unorthodox thing for a CRPG at the time. Why did you choose to go for this kind of combat gameplay? Would not party-based historical simulation rather call for turn-based as the more tactical kind of combat?

MicroProse had done a series of turn-based, hex-grid wargames a few years earlier. They were remarkably unsuccessful. Meanwhile, most successful RPGs in that time period were one-character real-time games like Ultima. I felt real-time with pause would appeal to more people than spending action points each “turn” to do various things with each character, much less deciding whether action resolution was “as you spend the points” or “simultaneously later.” The fact that action-point-spending games have died away suggests my judgment was correct.

One thing about the combat system that I still like is the armor penetration system combined with an endurance/death combat system. Heavily armored characters generally run out of endurance long before they die. Doing significant damage to heavily armored characters requires different weaponry than dealing with lighter armored foes. Therefore, weapon choice can and should vary depending on your opponents. A side benefit is that as long as someone in your party is still standing, there is a good chance that people won’t die. As a historical model it helps explain why late medieval battles rarely feature heavy casualties to heavily armored men on the winning side, while the losing side can suffer a serious loss of life. Agincourt in 1415 is a prime example.

One thing about the combat system that I still like is the armor penetration system combined with an endurance/death combat system. Heavily armored characters generally run out of endurance long before they die. Doing significant damage to heavily armored characters requires different weaponry than dealing with lighter armored foes. Therefore, weapon choice can and should vary depending on your opponents. A side benefit is that as long as someone in your party is still standing, there is a good chance that people won’t die. As a historical model it helps explain why late medieval battles rarely feature heavy casualties to heavily armored men on the winning side, while the losing side can suffer a serious loss of life. Agincourt in 1415 is a prime example.

Josh Sawyer: Darklands features an interesting blend of menu-driven gameplay, world map exploration, and small-scale combat maps. You've previously discussed that the game was initially conceived as having a lot of combat, but that you had other plans in mind as well. How were these other features conceived and developed?

The lead engineer on the game originally thought the game would be just combat (something like Diablo, which appeared four years later). I originally wanted more RPG, including a character generator and a menu-driven quasi-story system to link the battles. Originally I hoped to use a simple hypertext system to handle the whole menu mechanism, but the engineer who joined the project decided to write unique code. The strategic map terrain was originally envisioned as a mechanism for helping determine which kinds of battles a player would encounter. Eventually, most of the company’s design staff were drawn into quest generation.

RPG Codex: What were the main challenges involved in designing a "sandbox" CRPG of Darklands' proportions, from both a managerial and design standpoint?

The design was never completely mapped out at the start, not even in outline form. MicroProse had a very informal design methodology, strongly supported by Sid Meier, who always let his game designs “evolve” as he worked on them. As a result, I never appreciated all the effort the game would need until we were deep into it. This in turn meant that parts of the company crunched for more than a half year, struggling to get the game done and shipped. Under intense pressure to provide the company with revenue, we pushed it out with known bugs. We didn’t even know that some of the memory leak bugs meant that you had no chance of finishing certain mid-game quests, making it impossible to reach the endgame. This same bug also corrupted save game files, which really upset players! It took us an additional six months to find and fix all the serious bugs. This badly damaged the game’s success on store shelves.

RPG Codex: You probably had a lot of plans and ideas for a possible sequel to Darklands that had to be left unrealized, or at least a lot of ideas that did not make it into the game due to time and resource constraints. What were some of the things that had to be cut or that you planned for a sequel?

A true sandbox game would have more quests and activities than the characters could perform in any normal lifetime! I had originally hoped to have many quest storylines, not just one apocalyptic one. However, that was impractical given the growing time and cost. If the game had become an instant smash hit, then we could have done sequels with more storylines.

There is a lot more you can do with German history in that period. You can also add in things about the Hussites in Bohemia, the power of the Hanseatic League, the fall of the Teutonic Order, and rising Polish kingdom under the great Jagiellon dynasty. Adventures involving the struggle between the various papal factions could have been very interesting: the catholic church had three competing popes in the early 1400s.

Meanwhile, starting the late ‘90s, Jonathan Sumption has been slowing putting out an absolutely incredible multi-volume historyof the Hundred Years War. It is one of those seminal works that will be the defining history of the period for decades to come, much like S.E.Morison’s history of US Naval Operations in WWII or Oman’s history of the Peninsular wars. Armed with Sumption’s work, some great RPGs set in the Hundred Years War period are now possible.

There is a lot more you can do with German history in that period. You can also add in things about the Hussites in Bohemia, the power of the Hanseatic League, the fall of the Teutonic Order, and rising Polish kingdom under the great Jagiellon dynasty. Adventures involving the struggle between the various papal factions could have been very interesting: the catholic church had three competing popes in the early 1400s.

Meanwhile, starting the late ‘90s, Jonathan Sumption has been slowing putting out an absolutely incredible multi-volume historyof the Hundred Years War. It is one of those seminal works that will be the defining history of the period for decades to come, much like S.E.Morison’s history of US Naval Operations in WWII or Oman’s history of the Peninsular wars. Armed with Sumption’s work, some great RPGs set in the Hundred Years War period are now possible.

RPG Codex: What, in your view, has changed about video game, and in particular CRPG, design today compared to the time you were designing Darklands? Are there certain design trends that are worrisome to you or, on the contrary, that you especially appreciate?

I am never one to complain about the “direction” of gaming. I observe what does and does not work in various games, what makes and loses money. A designer must be informed by all this experience and knowledge in order to make a new “great” game. In a sense, any good designer must be a knowledgeable “games historian.”

In post-Darklands RPGs, I greatly admired Baldur’s Gate (1998) and its sequel. I consider them the finest and most polished “control a party” RPGs ever made. The original Diablo was a great one-character slug-fest with tons of replayability, but the interplay of story and characters was much less.

With the advent of Everquest in 1999, full 3D MMORPGs became the dominant form of RPG gaming through today. However, recent difficulties of SWTOR and 38 Studios suggest that the era of gigantic budget-busting MMORPGs is ending. There is still plenty of life left in the genre, provided you exercise business judgment and design creativity. I’d love a chance to lead an MMORPG team, especially after showing how a successful one can be done in just two years on a $15 million budget. Alas, I doubt it will happen. There are already too many other people occupying or trying to occupy all available positions.

Frankly, I believe the next “big” (financially viable) platform for RPGs is tablets. Look at the success of relatively unsophisticated games like Battleheart or Heroes vs Monsters on iOS!

In post-Darklands RPGs, I greatly admired Baldur’s Gate (1998) and its sequel. I consider them the finest and most polished “control a party” RPGs ever made. The original Diablo was a great one-character slug-fest with tons of replayability, but the interplay of story and characters was much less.

With the advent of Everquest in 1999, full 3D MMORPGs became the dominant form of RPG gaming through today. However, recent difficulties of SWTOR and 38 Studios suggest that the era of gigantic budget-busting MMORPGs is ending. There is still plenty of life left in the genre, provided you exercise business judgment and design creativity. I’d love a chance to lead an MMORPG team, especially after showing how a successful one can be done in just two years on a $15 million budget. Alas, I doubt it will happen. There are already too many other people occupying or trying to occupy all available positions.

Frankly, I believe the next “big” (financially viable) platform for RPGs is tablets. Look at the success of relatively unsophisticated games like Battleheart or Heroes vs Monsters on iOS!

RPG Codex: In a past interview, you said Microprose's downfall had to do with the way designers who worked there were only thinking about the games they wanted to make and not about the budget or people power required. Microprose, like many others at the time, was mainly about gaming, not business, and the business aspect suffered because of that. Would you agree that today we seem to have the opposite, "business first, gaming second" kind of situation, and what is your stance on that?

I don’t believe this is a question of “business vs gaming.” Making cool, attractive and interesting computer games takes man-years of work from a talented team. This is true even for facebook, tablet or mobile titles. You MUST have a functioning business to keep that team together and productive. Too much dreaming and insufficient attention to business means you’ll never make any games. Proper attention to business can give you a periodic opportunity to make great games. When you get that chance, don’t screw it up!

In an attempt to live by those words, since the 90s I have spent more and more time learning about project management. Thanks to a PMP, CSM, and multiple companies and projects practicing with them, I now know how to make great games without massive crunch time or bringing a studio to the brink of bankruptcy. Today I have the both the experience and professional skills to never allow the mistakes of the early 1990’s, or ever more recent disasters (such as 38 Studios).

However, simply having strong ability, experience and skill isn’t enough in today’s game industry. You also have to have to know the right people at the right time. The only reliable way to arrange this is to tirelessly promote yourself. Unfortunately for me, I don’t have the ego to do that.

In an attempt to live by those words, since the 90s I have spent more and more time learning about project management. Thanks to a PMP, CSM, and multiple companies and projects practicing with them, I now know how to make great games without massive crunch time or bringing a studio to the brink of bankruptcy. Today I have the both the experience and professional skills to never allow the mistakes of the early 1990’s, or ever more recent disasters (such as 38 Studios).

However, simply having strong ability, experience and skill isn’t enough in today’s game industry. You also have to have to know the right people at the right time. The only reliable way to arrange this is to tirelessly promote yourself. Unfortunately for me, I don’t have the ego to do that.

RPG Codex: Given the recent Kickstarter success stories of Tim Schafer and Brian Fargo, what do you think of crowdfunding as a way of independent video game publishing and would you consider turning to Kickstarter to fund a sequel or a spiritual successor to Darklands? Ideally, if given enough time and resources, how would you go about creating a game like Darklands today?

I have given some thought to kickstarter recently, and a number of people have mentioned it to me. Known quantities do have an easier time attracting kickstarter money, and a number of my games fall into that category. There are very interesting possiblities in building more polished and professional games for the upcoming “tablet platform war” between Win8, iOS and Android. The $1-$2 mil kickstarter might generate could be sufficient for a first title on one of those platforms.

Actually, a really cool sandbox MMORPG or single-player CRPG is possible as well. A discussion of how that might work is a whole article in itself. Unfortunately, development cost for PC MMORPGs and CRPGs is much higher than tablets. Any plan is unlikely to get much traction now that SWTOR has decisively proved that you can’t copy WoW’s success, no matter how good the license or how much you spend.

Actually, a really cool sandbox MMORPG or single-player CRPG is possible as well. A discussion of how that might work is a whole article in itself. Unfortunately, development cost for PC MMORPGs and CRPGs is much higher than tablets. Any plan is unlikely to get much traction now that SWTOR has decisively proved that you can’t copy WoW’s success, no matter how good the license or how much you spend.

RPG Codex: Thank you for your time!

We thank J.E. Sawyer for contributing to the interview and writing up the retrospective. Thanks are also due to Jaesun, Monolith and Zed for their feedback and suggestions.