RPG Codex Book Review: Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play

RPG Codex Book Review: Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play

Review - posted by Crooked Bee on Sun 27 May 2012, 20:13:21

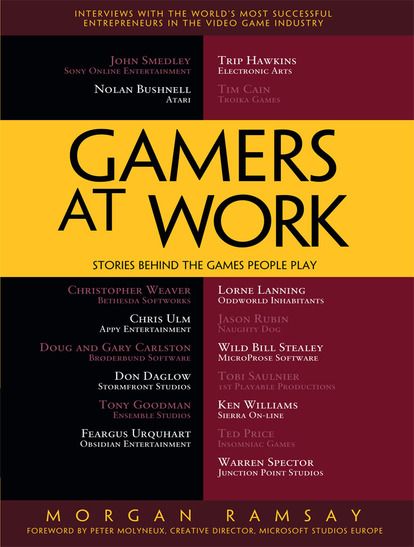

Tags: Book; Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play; Morgan RamsayMorgan Ramsay, Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play, Apress, 2012, 356pp., $29.99 (pbk), ISBN 9781430233510.

[Reviewed by grotsnik]

Morgan Ramsay’s Gamers At Work: Stories Behind The Games People Play features seventeen in-depth interviews with a diverse bag of industry figures, exploring their various experiences in starting up their own companies: Warren Spector, Tim Cain, Nolan Bushnell, EA founder Trip Hawkins, Stormfront’s Don Daglow, Sierra Online’s Ken Williams, Oddworld’s Lorne Lanning, John Smedley, Bethesda’s Christopher Weaver, Naughty Dog’s Jason Rubin, Feargus Urquhart, Doug and Gary Carlston, Tony Goodman of Age of Empires fame, Ted Price, Chris Ulm and Tobi Saulnier. (It also comes with an odd little four-paragraph foreword by Peter Molyneux, who reflects upon such troubling universal questions as, “Could we see a day when the framework of a game helps us cross a cultural divide?” while saying nothing to indicate that he’s actually read any of the interviews.) Within, the interviewees explain their business practices and the structures of their organisations, go back over the games and the decisions that brought them success, as well as, frequently, the mistakes that led to corporate sell-out or disaster.

So do these insights add up to an essential guide for would-be industry types everywhere, a cornucopia of wisdom, business acumen and genius for start-up developers and publishers everywhere to abide by, as the book’s introduction and marketing suggest? Well... no, to get it out of the way from the beginning, of course they don’t. For one thing, the interviewees’ success stories are all too much built on good fortune, timing and circumstance to provide serious reference points; most notably, the initial rise of Doug and Gary Carlston’s publishing start-up Broderbund Software seems to have been almost entirely a result of their impressing a prestige-obsessed Japanese developer by putting a copy of Harvard Magazine on their coffee table (“Oh! Hahvahd!” was apparently the delighted exclamation). Certainly there’s some perfectly laudable advice on how to handle a team - don’t treat your workers like cattle to be milked until they collapse! Make provision for them if they lose their jobs! - but it’s unlikely to shock anyone who isn’t already a CEO.

And it’s when the interviewees are prompted explicitly for their thoughts on a winning business formula, too, that they tend to fall back on obvious generalities; President of Sony Online John Smedley defines his secret to success as ‘You get people who say “Hey, I have a great idea”, and everybody says, “Yeah, that is a great idea. Let’s do that.”’ Christopher Weaver’s answer is less Dude-ish, if ultimately, in a robotic kind of way, just as unhelpful; “The way that you become a real force is to have enough quality teams that you can asynchronously develop and release triple-A products and capitalise on their quality at the same time your previous product is converting from its main sell cycle to a secondary one. If you can get the multiple timelines to overlap properly, you can keep the sine wave at positive values.” Ah.

What Gamers At Work does do, though, is provide an unusually diverse series of self-portraits, as the industry figures provide highly subjective retrospectives on their careers and business practices and, in doing so, reveal a great deal about how they'd like to paint themselves, their careers, and the industry itself. ‘Wild’ Bill Stealey’s interview, amusingly, cuts back and forth between an obvious sweaty man-crush on Sid Meier and a deranged obsession with his own past in the Air Force; in one characteristic sequence, he recalls reacting with upright military horror at the sight of Sid pirating competitors’ games in order to ‘review’ them; “As an Air Force Academy graduate, I can’t review games without paying for them. That’s what we called quibbling at the Air Force Academy.” Elsewhere, Trip Hawkins throws a bit of a hissy fit when Ramsay asks him, perfectly innocently, if there were any co-founders at EA. (Apparently there weren't, and anyone who says otherwise is a liar.) Tony Goodman, having previously insisted that he's in the business to "make the world a better place", rhapsodises about the freakishly decadent Roman-style orgy laid on for him by Microsoft. which apparently climaxed with a 400-pound lion escaping from its cage. A few of the characters emerge as honest and genuinely given to self-criticism; others, inevitably, are rather more prone to self-delusion (an otherwise candid Ken Williams at one point refers to Phantasmagoria I and II as “one of the greatest series ever made”. Oh, Ken); and at least one or two, despite their own best efforts, come across as unsurprisingly unpleasant, cut-throat and self-concerned. Nearly all of them, however, do have interesting - or at the very least, telling - stories about their careers.

And, of course, many of these stories result in good old-fashioned insider bitching; astonishingly enough, the big mistakes almost always turn out to have been the fault of someone else. Rubin talks about the “spite and contractual misbehavior” at Universal. Hawkins and Bushnell excoriate, for very different reasons, Atari, while the Chuck E. Cheese magnate also snipes at the “dim” executives at Warner. ‘Wild’ Bill Stealey claims that Hawkins tried to push towards merging EA and Microprose in the late ‘80s, a fact which Hawkins certainly leaves out of his recollections in his own interview (it’s a pity Ramsay doesn’t appear to have conducted a follow-up chat to pursue this particular line of enquiry). And Tim Cain chastises Atari for rushing the development of TOEE, and Activision, all too gently, in my opinion, for their mishandling of Bloodlines.

The specificity of Gamers At Work’s intent ends up being one of the book’s real strengths; it helps prevent sprawl in interviews about careers sometimes spanning several decades, but more importantly, it encourages the interviewees towards straightforward, nuts-and-bolts answers about how their companies grew and functioned, without giving them much opportunity to stray into self-aggrandising PR blather (though one or two still manage to do so; Tony Goodman memorably justifies selling Ensemble Studios off to Microsoft with the phrase, “I wanted to enrich myself by enriching my employees”, and boasts of asking all job applicants “esoteric questions” such as “What are your hopes and dreams in life?”). But the pure focus on entrepreneurialism can also be limiting and frustrating; it’s hard, for example, not to come away aggrieved by a retrospective interview with Warren Spector that skips past the entire first twenty years of his career in order to discuss in depth his project with startup studio Junction Point, Epic Mickey for the Nintendo Wii.

It also means that when the business-folk do let slip an intriguing (or, as frequently, depressing) comment about their thoughts on game design, Ramsay tends to ignore it and return to discussing turnovers, salaries and mergers. Given the chance, I’d have liked to see him press Hawkins on his awful assertion that challenge in games is no longer relevant, since it’s “too intimidating and embarrassing to fail...there’s nothing wrong with helping players release hormones like dopamine and feel good about themselves.” (This is the same Hawkins who rather more poetically heralded the Playstation 2 as “a new canvas for humanity that takes us back to our nature” and “as important as the printing press” - the printing press being that other well-known invention apparently good for nothing more than doping its users into a false sense of achievement.)

Ramsay works his interviewees gently; the majority of his questions are little more than prompts to keep things moving along. It’s the right approach, professional without being too controlling, and it usually does its job admirably well in leading his subjects through their careers one moment at a time. There is, however, a problem throughout with the book’s editing. A number of exchanges simply don’t go anywhere, and could have been excised or merged into other answers without damaging the flow of the interviews. Sometimes Ramsay throws in a question that makes his subject clam up, as when he tries to encourage Nolan Bushnell to talk about how Atari ‘recovered’ post-1983 (the magnificently brusque response: “It never did.”), which is fine - but we shouldn’t be reading this rough-around-the-edges stuff in the final manuscript. Once or twice, too, interviewer and interviewee get drawn into a chummy, irrelevant diversion that goes on too long; fun though it must have been for Ramsay to listen to Bushnell explaining the mechanics of multilevel pinball machines, or Gateway to/Treasures of the Savage Frontier designer Don Daglow theorising at length about baseball strategy, this stuff really didn’t need to be kept on the record.

For readers of the Codex, the real draw is the Tim Cain interview, which covers ground from the problems within Interplay that led to his departure, to the creation of Arcanum and The Temple of Elemental Evil, to, finally, Bloodlines and the collapse of Troika. (Gold Box and Obsidian fans may also enjoy the Daglow and Urquhart chapters, respectively, although the former only really mentions his work on RPGs in passing, and the latter is one of the weaker interviews, focusing predominantly on the problems and benefits of using other developers' engines). Even if you've heard most of it before, it's a good read - and, incidentally, freely available in full as part of the book's Google Books preview - with frank analysis of the various petty conflicts and power struggles in Interplay's offices (Brian Fargo, interestingly, comes across as well-intentioned but genuinely blind to the tensions breaking up his workforce), and descriptions both of Troika's lax attitude towards business and their troubles dealing with Atari and Activision. In the end, he admits, "I didn't particularly enjoy running a business, and Leonard and Jason didn't either," which does perhaps make him an odd candidate for a book celebrating entrepreneurialism, but his passion for the games themselves and utter lack of interest in profiteering are certainly refreshing when they're coming from amongst so many hyper-ambitious suits.

The final impression the reader gets from the majority of these figures and where they see the gaming industry going in the near future, however, is edifying if not exactly cheering. Many of them now seem to be entirely focused on the mobile and casual browser-gaming experience. Chris Ulm of Appy Entertainment boasts of their “games for the rest of us”, “short blasts of fun” for mobile devices such as Zombie Pizza and FaceFighter, which allows its users to upload photographs of those they dislike onto their phones and then batter away at them virtually until their enemies’ faces are a mess of bruises. (A photograph of Mr Ulm’s face is conveniently featured at the very beginning of the interview.) Warren Spector enthuses, bizarrely, “I want...games like Deus Ex and the Ultima games and Disney Epic Mickey to go on after I’m retired”. The idea that these projects might not all necessarily belong in the same sentence simply doesn’t seem to occur to him; apparently he’s quite happy about where he's ended up and where we’re all headed. Still, even if many of the entrepreneurs’ recollections and self-examinations don’t inspire much hope for the industry as a whole, Gamers at Work is at least a frequently very engaging record of their individual pasts.

[Reviewed by grotsnik]

“I invested a lot of time with key editors (in gaming journalism), seeding the idea that Age Of Empires would be ‘revolutionary’ and become ‘a phenomenon’...When the first early previews began appearing, they were using the terms that we seeded: ‘revolutionary’ and ‘phenomenal’. These early opinions were then picked up and echoed by other publications, creating a snowball effect. Eventually, all the publications would get on board with this message just so they didn’t look out of touch.”

- Ensemble Studios’ Tony Goodman, on a better time for gaming journalism

“At least for me, it was totally opportunistic.”

- Nolan Bushnell

- Ensemble Studios’ Tony Goodman, on a better time for gaming journalism

“At least for me, it was totally opportunistic.”

- Nolan Bushnell

Morgan Ramsay’s Gamers At Work: Stories Behind The Games People Play features seventeen in-depth interviews with a diverse bag of industry figures, exploring their various experiences in starting up their own companies: Warren Spector, Tim Cain, Nolan Bushnell, EA founder Trip Hawkins, Stormfront’s Don Daglow, Sierra Online’s Ken Williams, Oddworld’s Lorne Lanning, John Smedley, Bethesda’s Christopher Weaver, Naughty Dog’s Jason Rubin, Feargus Urquhart, Doug and Gary Carlston, Tony Goodman of Age of Empires fame, Ted Price, Chris Ulm and Tobi Saulnier. (It also comes with an odd little four-paragraph foreword by Peter Molyneux, who reflects upon such troubling universal questions as, “Could we see a day when the framework of a game helps us cross a cultural divide?” while saying nothing to indicate that he’s actually read any of the interviews.) Within, the interviewees explain their business practices and the structures of their organisations, go back over the games and the decisions that brought them success, as well as, frequently, the mistakes that led to corporate sell-out or disaster.

So do these insights add up to an essential guide for would-be industry types everywhere, a cornucopia of wisdom, business acumen and genius for start-up developers and publishers everywhere to abide by, as the book’s introduction and marketing suggest? Well... no, to get it out of the way from the beginning, of course they don’t. For one thing, the interviewees’ success stories are all too much built on good fortune, timing and circumstance to provide serious reference points; most notably, the initial rise of Doug and Gary Carlston’s publishing start-up Broderbund Software seems to have been almost entirely a result of their impressing a prestige-obsessed Japanese developer by putting a copy of Harvard Magazine on their coffee table (“Oh! Hahvahd!” was apparently the delighted exclamation). Certainly there’s some perfectly laudable advice on how to handle a team - don’t treat your workers like cattle to be milked until they collapse! Make provision for them if they lose their jobs! - but it’s unlikely to shock anyone who isn’t already a CEO.

And it’s when the interviewees are prompted explicitly for their thoughts on a winning business formula, too, that they tend to fall back on obvious generalities; President of Sony Online John Smedley defines his secret to success as ‘You get people who say “Hey, I have a great idea”, and everybody says, “Yeah, that is a great idea. Let’s do that.”’ Christopher Weaver’s answer is less Dude-ish, if ultimately, in a robotic kind of way, just as unhelpful; “The way that you become a real force is to have enough quality teams that you can asynchronously develop and release triple-A products and capitalise on their quality at the same time your previous product is converting from its main sell cycle to a secondary one. If you can get the multiple timelines to overlap properly, you can keep the sine wave at positive values.” Ah.

“In our culture, we still worship the richest guy. But come on, is that all? Is that really it? Is that how shallow we are? Is that all the fuck it’s about? Take a look around you. Did I see his sailboat? Fuck his sailboat and fuck him because the guy’s a turd.”

- Lorne Lanning, apparently not totally onboard with the message of the book

- Lorne Lanning, apparently not totally onboard with the message of the book

What Gamers At Work does do, though, is provide an unusually diverse series of self-portraits, as the industry figures provide highly subjective retrospectives on their careers and business practices and, in doing so, reveal a great deal about how they'd like to paint themselves, their careers, and the industry itself. ‘Wild’ Bill Stealey’s interview, amusingly, cuts back and forth between an obvious sweaty man-crush on Sid Meier and a deranged obsession with his own past in the Air Force; in one characteristic sequence, he recalls reacting with upright military horror at the sight of Sid pirating competitors’ games in order to ‘review’ them; “As an Air Force Academy graduate, I can’t review games without paying for them. That’s what we called quibbling at the Air Force Academy.” Elsewhere, Trip Hawkins throws a bit of a hissy fit when Ramsay asks him, perfectly innocently, if there were any co-founders at EA. (Apparently there weren't, and anyone who says otherwise is a liar.) Tony Goodman, having previously insisted that he's in the business to "make the world a better place", rhapsodises about the freakishly decadent Roman-style orgy laid on for him by Microsoft. which apparently climaxed with a 400-pound lion escaping from its cage. A few of the characters emerge as honest and genuinely given to self-criticism; others, inevitably, are rather more prone to self-delusion (an otherwise candid Ken Williams at one point refers to Phantasmagoria I and II as “one of the greatest series ever made”. Oh, Ken); and at least one or two, despite their own best efforts, come across as unsurprisingly unpleasant, cut-throat and self-concerned. Nearly all of them, however, do have interesting - or at the very least, telling - stories about their careers.

And, of course, many of these stories result in good old-fashioned insider bitching; astonishingly enough, the big mistakes almost always turn out to have been the fault of someone else. Rubin talks about the “spite and contractual misbehavior” at Universal. Hawkins and Bushnell excoriate, for very different reasons, Atari, while the Chuck E. Cheese magnate also snipes at the “dim” executives at Warner. ‘Wild’ Bill Stealey claims that Hawkins tried to push towards merging EA and Microprose in the late ‘80s, a fact which Hawkins certainly leaves out of his recollections in his own interview (it’s a pity Ramsay doesn’t appear to have conducted a follow-up chat to pursue this particular line of enquiry). And Tim Cain chastises Atari for rushing the development of TOEE, and Activision, all too gently, in my opinion, for their mishandling of Bloodlines.

The specificity of Gamers At Work’s intent ends up being one of the book’s real strengths; it helps prevent sprawl in interviews about careers sometimes spanning several decades, but more importantly, it encourages the interviewees towards straightforward, nuts-and-bolts answers about how their companies grew and functioned, without giving them much opportunity to stray into self-aggrandising PR blather (though one or two still manage to do so; Tony Goodman memorably justifies selling Ensemble Studios off to Microsoft with the phrase, “I wanted to enrich myself by enriching my employees”, and boasts of asking all job applicants “esoteric questions” such as “What are your hopes and dreams in life?”). But the pure focus on entrepreneurialism can also be limiting and frustrating; it’s hard, for example, not to come away aggrieved by a retrospective interview with Warren Spector that skips past the entire first twenty years of his career in order to discuss in depth his project with startup studio Junction Point, Epic Mickey for the Nintendo Wii.

It also means that when the business-folk do let slip an intriguing (or, as frequently, depressing) comment about their thoughts on game design, Ramsay tends to ignore it and return to discussing turnovers, salaries and mergers. Given the chance, I’d have liked to see him press Hawkins on his awful assertion that challenge in games is no longer relevant, since it’s “too intimidating and embarrassing to fail...there’s nothing wrong with helping players release hormones like dopamine and feel good about themselves.” (This is the same Hawkins who rather more poetically heralded the Playstation 2 as “a new canvas for humanity that takes us back to our nature” and “as important as the printing press” - the printing press being that other well-known invention apparently good for nothing more than doping its users into a false sense of achievement.)

“I did have my own cutouts, because I was taller than Sid. Sid didn’t wear flight suits. I did. We made those cutouts because EA put up cutouts of Chuck Yeager, trying to sell an EA flying game. Those cutouts were only four-feet high. I made my cutout life-size - seven feet tall! I wonder if there’s a picture of those anywhere on the Web? I bet there is.”

- ‘Wild’ Bill Stealey

- ‘Wild’ Bill Stealey

Ramsay works his interviewees gently; the majority of his questions are little more than prompts to keep things moving along. It’s the right approach, professional without being too controlling, and it usually does its job admirably well in leading his subjects through their careers one moment at a time. There is, however, a problem throughout with the book’s editing. A number of exchanges simply don’t go anywhere, and could have been excised or merged into other answers without damaging the flow of the interviews. Sometimes Ramsay throws in a question that makes his subject clam up, as when he tries to encourage Nolan Bushnell to talk about how Atari ‘recovered’ post-1983 (the magnificently brusque response: “It never did.”), which is fine - but we shouldn’t be reading this rough-around-the-edges stuff in the final manuscript. Once or twice, too, interviewer and interviewee get drawn into a chummy, irrelevant diversion that goes on too long; fun though it must have been for Ramsay to listen to Bushnell explaining the mechanics of multilevel pinball machines, or Gateway to/Treasures of the Savage Frontier designer Don Daglow theorising at length about baseball strategy, this stuff really didn’t need to be kept on the record.

For readers of the Codex, the real draw is the Tim Cain interview, which covers ground from the problems within Interplay that led to his departure, to the creation of Arcanum and The Temple of Elemental Evil, to, finally, Bloodlines and the collapse of Troika. (Gold Box and Obsidian fans may also enjoy the Daglow and Urquhart chapters, respectively, although the former only really mentions his work on RPGs in passing, and the latter is one of the weaker interviews, focusing predominantly on the problems and benefits of using other developers' engines). Even if you've heard most of it before, it's a good read - and, incidentally, freely available in full as part of the book's Google Books preview - with frank analysis of the various petty conflicts and power struggles in Interplay's offices (Brian Fargo, interestingly, comes across as well-intentioned but genuinely blind to the tensions breaking up his workforce), and descriptions both of Troika's lax attitude towards business and their troubles dealing with Atari and Activision. In the end, he admits, "I didn't particularly enjoy running a business, and Leonard and Jason didn't either," which does perhaps make him an odd candidate for a book celebrating entrepreneurialism, but his passion for the games themselves and utter lack of interest in profiteering are certainly refreshing when they're coming from amongst so many hyper-ambitious suits.

The final impression the reader gets from the majority of these figures and where they see the gaming industry going in the near future, however, is edifying if not exactly cheering. Many of them now seem to be entirely focused on the mobile and casual browser-gaming experience. Chris Ulm of Appy Entertainment boasts of their “games for the rest of us”, “short blasts of fun” for mobile devices such as Zombie Pizza and FaceFighter, which allows its users to upload photographs of those they dislike onto their phones and then batter away at them virtually until their enemies’ faces are a mess of bruises. (A photograph of Mr Ulm’s face is conveniently featured at the very beginning of the interview.) Warren Spector enthuses, bizarrely, “I want...games like Deus Ex and the Ultima games and Disney Epic Mickey to go on after I’m retired”. The idea that these projects might not all necessarily belong in the same sentence simply doesn’t seem to occur to him; apparently he’s quite happy about where he's ended up and where we’re all headed. Still, even if many of the entrepreneurs’ recollections and self-examinations don’t inspire much hope for the industry as a whole, Gamers at Work is at least a frequently very engaging record of their individual pasts.

There are 17 comments on RPG Codex Book Review: Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play