RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Michael Cranford on Bard's Tale, Interplay, and Centauri Alliance

RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Michael Cranford on Bard's Tale, Interplay, and Centauri Alliance

Codex Interview - posted by Crooked Bee on Fri 27 September 2013, 17:25:03

Tags: Broderbund Software; Centauri Alliance; Interplay; Michael Cranford; Retrospective Interview; The Bard's Tale; The Bard's Tale II: The Destiny KnightRPG Codex Retrospective Interviews is a series that grew out of our fascination with the rich history of computer role-playing games. It focuses on developers and individual titles that made a unique or significant contribution to the genre, aiming to cover a developer's career and approach to RPG design or, respectively, the most relevant aspects of the game in question and the design philosophy behind it.

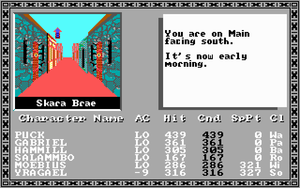

In 1985, Interplay released Tales of the Unknown: Vol. I: The Bard’s Tale, their own “Wizardry killer” designed and programmed by Brian Fargo’s high school friend Michael Cranford. The game was a smashing success for the company. As Fargo said in his 2011 Matt Chat interview, The Bard’s Tale I “was the product that put us on the map, it was the thing that made us earn significant royalties so we could bring the company to the next level.” In an important way, it was Michael Cranford who kick-started Interplay’s future as RPG developer and publisher. At the same time, Cranford was unhappy about the contract Interplay offered him and left the company after The Bard’s Tale II release. In 1990, he designed his last game, Centauri Alliance, a unique sci-fi CRPG published by Brøderbund for the Apple II and Commodore 64. The choice of platforms coupled with the game’s delayed release turned out to be really unfortunate for its publicity and sales, and no further titles in the Centauri Alliance universe were made. Currently Michael Cranford is CEO at Ninth Degree.

In this interview, Michael talks about the Bard’s Tale series, Interplay, his falling out with Brian Fargo, as well as Centauri Alliance and Brøderbund. We are grateful to Michael for taking his time to do this interview.

(Photo courtesy of Michael Cranford himself.)

How did your idea to, as you put it elsewhere, "blow Wizardry away" originate? In what ways did you intend your games to be different from Wizardry from a design standpoint?

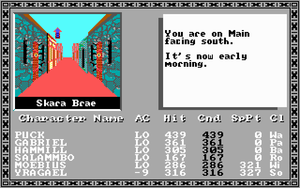

Wizardry III (1983) vs Bard's Tale I (1985), both for DOS. Even as late as 1987, at the time Bard's Tale II had already been released, Wizardry IV still kept the wireframe dungeons.

Why did you decide to make the Bard and his music the central part of the game’s concept? What did you like the most about that character class?

In another interview, you have said that you intended Bard’s Tale II to be tough but not as tough as it turned out to be, and blamed that on a lack of playtesting. The game's manual lists three playtesters - I assume that wasn't enough? How much time did you have to playtest the game?

On the other hand, high difficulty definitely remains an important part of the Bard’s Tale legacy and some people like the series for that. What is your stance on having RPGs that only appeal to really “hardcore” players? And what was your own style of play when it came to P&P sessions – how “hardcore” were the pen and paper adventures you DMed?

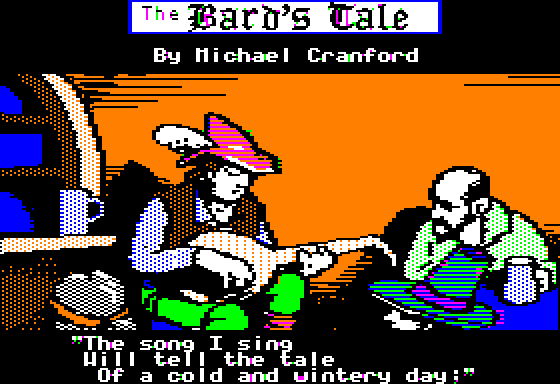

Apple II title screen for Tales of the Unknown: Vol. I - The Bard's Tale, as the first game in the series was officially called.

When entering the stables in Bard's Tale I, we are told that the horses have been eaten by monsters. Was it intended at any time during the development of BT1 to implement the purchasing of horses to perhaps exit the city of Skara Brae after Mangar's spell of eternal winter was destroyed? Or was there ever to be any plot or additional dungeons or secret passages involving the stables?

The real-time puzzles called “snares” in Bard’s Tale II are good in concept, but they also seem to be one of the more frustrating parts of the game. How did you come up with the idea for them? Were you happy with the implementation of snares and how they were received?

Bard’s Tale II also allowed the player to summon monsters to join the group. What inspired that idea?

Bard’s Tale I only took place in one town, whereas the second game has six towns as well as a large world to explore. Was that the direction you wanted the series to take from the start? If so, why hadn’t you implemented a larger gameworld in the first game as well?

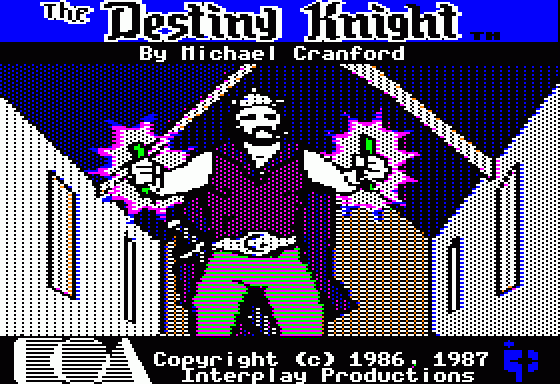

Apple II title screen for The Bard's Tale II: The Destiny Knight, the second game in the series - and the last one designed by Michael Cranford. For The Bard's Tale III, Bill "Burger" Heineman took over after Cranford had a falling out with Fargo and left Interplay.

To approach the same question from a different angle, Bard's Tale II was released only about a year after the release of the original Bard's Tale and included quite a few enhancements over the original (huge gameworld, banks, casinos, ranged combat, more spells, real time snares, more monster abilities and monster inventory, etc.). How was so much accomplished in such a small window?

Personally I loved the level design in the Bard’s Tale games – with all the spinners, anti-magic zones, darkness zones, etc. How did you approach designing the layout of the games’ dungeons, and what are your favorite Bard’s Tale I and/or II levels (if you can recall that)?

There is a story (I don’t know to what extent it is true) told by “Burger” Heineman as well as by Brian Fargo about how you held the Bard’s Tale floppy disk hostage in order to make Fargo change the terms of the deal between you and Interplay. Could you tell us your side of that story, if you feel like talking about it?

In general, how would you describe your experience of working with Interplay and Brian Fargo? What are the moments you remember most and least fondly about it? In hindsight, do you think something could have been done for you to stay at Interplay and further develop the ideas you had in mind for the Bard’s Tale series?

After Bard’s Tale II, you not only left Interplay, you said you were also disillusioned by the industry as a whole – and so you went back to the university to study philosophy and theology. Could you tell us more about your experience with the industry at the time and what about it made you feel the way you did?

Have you played Bard’s Tale III or Dragon Wars? If you have, what are your thoughts on those games? What did you enjoy about them, and what did you not?

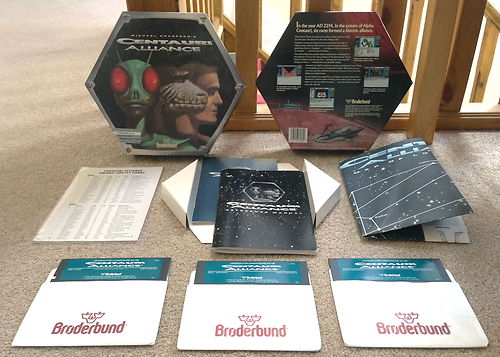

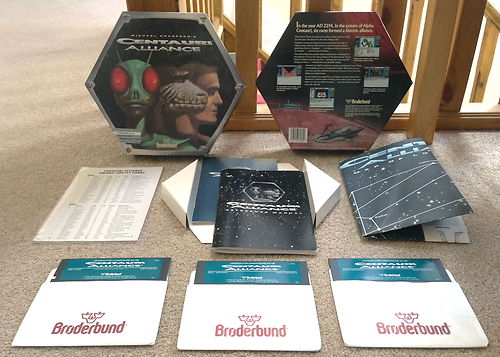

Centauri Alliance came in a hexagon-shaped box which included a manual, a field guide, a psionic ability chart and a huge star map.

Could you tell us how you got to work with Brøderbund on Centauri Alliance?

Was it your or Brøderbund’s decision to develop the game exclusively for the Apple II and Commodore 64 platforms (which ultimately contributed to its relative obscurity)? Why didn’t you create an Amiga or DOS version of Centauri Alliance after you were done with the Apple II and C64 ones?

You say the Centauri Alliance development got stalled. Why did that happen?

The “RPG side” of Brøderbund, and the company’s history at the time of Centauri Alliance's release, remains relatively little known to this day. Coud you tell us more about the people you interacted with at Brøderbund, and what you enjoyed (or didn’t enjoy) about the company culture and atmosphere there at the time? How supportive were they about your project?

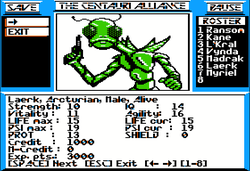

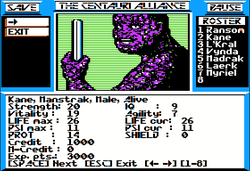

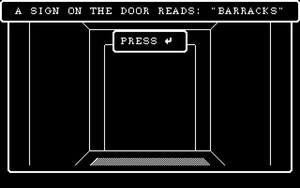

Centauri Alliance's combat screen as seen on the C64. Combat areas in the game differ in size; black squares are obstacles that cannot be crossed.

In Centauri Alliance, you went from the Bard's Tale-style combat to a hex grid, introducing a unique compromise between the first person menu-based combat and the full-blown tactical isometric combat characteristic of e.g. the Goldbox games - your party moved around on the hex grid but was only represented by a single sprite. What motivated that design decision, and why didn't you go for a Goldbox-like combat?

For Centauri Alliance, you created a huge sci-fi universe with unique races. What were your inspirations for the game's setting? How did you approach designing the psionic abilities - and in particular, what motivated you to introduce the shape-changing ("metamorph") skills exclusive to the Praktor race?

Can you tell us more about the sci-fi book you're working on?

"This could turn into the next big science fiction series," said the 1990 QuestBusters review of Centauri Alliance. Were the first game's sales too poor for Brøderbund to be interested in turning it into a series? Did you have plans for Centauri Alliance II, and if so, what can you recall about them?

Despite the mixed reviews that Bard’s Tale II’s real-time snares received, you also added timed puzzles to Centauri Alliance (such as running through a maze to shut down the reactor before it explodes). Do you believe real-time elements can add something to a turn-based RPG?

Speaking of real-time elements, why were random encounters in BT1 and BT2 checked in real time instead of each time you moved or turned? Sometimes you would end up with multiple battles in the same square since you didn't even have time to distribute new loot before being beset by a new monster group.

Do you have any thoughts on the ongoing "oldschool" RPG revival fueled by Kickstarter projects like Project Eternity or Wasteland 2 and indie titles like Legend of Grimrock? Even a major publisher like Ubisoft is now designing Might and Magic X as a grid- and turn-based first-person RPG in the vein of World of Xeen. Why do you think oldschool RPGs are making a comeback?

Ultima 1 went to Ultima 9, Wizardry went from 1 to 8, and even Might and Magic has a number 10 in the works. Bard's Tale stopped at 3, but where do you think the Bard's Tale series would be if it had continued to this day and if you were still working on it? What are the main things you would change about the series' design today compared to that of the original Bard’s Tale games?

Do you happen to have any plans for remakes or Kickstarter projects? Generally, do you see yourself working in video games again?

Thank you for your time.

Special thanks go to the people who submitted their questions for this interview! Your contribution was much appreciated.

If you enjoyed this interview, be sure to check out the other ones in our retrospective interview series.

In 1985, Interplay released Tales of the Unknown: Vol. I: The Bard’s Tale, their own “Wizardry killer” designed and programmed by Brian Fargo’s high school friend Michael Cranford. The game was a smashing success for the company. As Fargo said in his 2011 Matt Chat interview, The Bard’s Tale I “was the product that put us on the map, it was the thing that made us earn significant royalties so we could bring the company to the next level.” In an important way, it was Michael Cranford who kick-started Interplay’s future as RPG developer and publisher. At the same time, Cranford was unhappy about the contract Interplay offered him and left the company after The Bard’s Tale II release. In 1990, he designed his last game, Centauri Alliance, a unique sci-fi CRPG published by Brøderbund for the Apple II and Commodore 64. The choice of platforms coupled with the game’s delayed release turned out to be really unfortunate for its publicity and sales, and no further titles in the Centauri Alliance universe were made. Currently Michael Cranford is CEO at Ninth Degree.

In this interview, Michael talks about the Bard’s Tale series, Interplay, his falling out with Brian Fargo, as well as Centauri Alliance and Brøderbund. We are grateful to Michael for taking his time to do this interview.

(Photo courtesy of Michael Cranford himself.)

How did your idea to, as you put it elsewhere, "blow Wizardry away" originate? In what ways did you intend your games to be different from Wizardry from a design standpoint?

I loved the game, and spent many long hours playing it in my apartment in Berkeley. As a programmer, the limitations of the game were obvious to me (largely a result of the fact that it was programmed in Pascal on a computer with 48K of memory). I had already begun to develop videos games in assembly language, and it struck me that I could provide a much bigger, more graphical, memory-efficient, and detailed game than Wizardry. While I couldn’t then play and enjoy it myself, I knew that I would reach and enthrall tens or hundreds of thousands of people like me, if I did build something better.

I’ve also been an artist and writer most of my life, and an avid reader of fantasy fiction, and I had previously created and illustrated numerous D&D dungeons (for friends, nothing that was ever published). I knew that I could develop a plot for the game that was going to be more interesting than simply locating and finding a sword with a higher hit and damage rating.

I had a vision for abandoning Wizardry’s wireframe corridors and introducing framed animation of textured walls that moved toward you (a pseudo-3D effect). I wanted a world that looked more real than Wizardry’s. That was my primary design departure. I also wanted more magic involved in the game; hack and slash wasn’t as interesting to me.

I’ve also been an artist and writer most of my life, and an avid reader of fantasy fiction, and I had previously created and illustrated numerous D&D dungeons (for friends, nothing that was ever published). I knew that I could develop a plot for the game that was going to be more interesting than simply locating and finding a sword with a higher hit and damage rating.

I had a vision for abandoning Wizardry’s wireframe corridors and introducing framed animation of textured walls that moved toward you (a pseudo-3D effect). I wanted a world that looked more real than Wizardry’s. That was my primary design departure. I also wanted more magic involved in the game; hack and slash wasn’t as interesting to me.

Wizardry III (1983) vs Bard's Tale I (1985), both for DOS. Even as late as 1987, at the time Bard's Tale II had already been released, Wizardry IV still kept the wireframe dungeons.

Why did you decide to make the Bard and his music the central part of the game’s concept? What did you like the most about that character class?

I don’t remember that it started that way. I had worked for a few years for a company in the San Francisco area, doing platform conversions of arcade games, and during that time, there was a guy (Larry Holland) who was a musician and programmer, and he was the go-to guy for sound effects and music behind video games. I already had developed code to “stream” music by putting it into the interrupt on the Apple II (basically, a timer event that you could stuff code into), something I really hadn’t seen anyone else do. So I had it in my mind that I would have a bard class in the game who would cast a “spell” over a time duration with different effects to help the group, and that spell would be audible (background music). It’s possible there was a book that I read that inspired it, but if so, I don’t remember. It was just a natural combination of the code to stream and play music on the Apple, and a desire to emphasize interesting magical effects in the game. I also love music. This particular class simply stood out the most during development, because of the unique nature of the class and the musical aspect of the game, and we had a consultant who named the game after the bard class. I didn’t name the game. So the bard became central because people at Interplay and EA loved it.

In another interview, you have said that you intended Bard’s Tale II to be tough but not as tough as it turned out to be, and blamed that on a lack of playtesting. The game's manual lists three playtesters - I assume that wasn't enough? How much time did you have to playtest the game?

I personally didn’t play the game a lot; I guess what I came to learn was that developing games (and programming generally) was a lot more fun to me than playing them. Especially my own stuff. So I was constantly developing back then. I created a dungeon editor that made it possible (by BT2) for anyone to create dungeon levels and populate them with monsters, for example. I always had some new thing to work on, some problem to solve. I really should have spent more time playing my own game. I didn’t have any idea it would be that difficult. And I was a kid, you know? This was long before I learned that the best things in life are simple.

On the other hand, high difficulty definitely remains an important part of the Bard’s Tale legacy and some people like the series for that. What is your stance on having RPGs that only appeal to really “hardcore” players? And what was your own style of play when it came to P&P sessions – how “hardcore” were the pen and paper adventures you DMed?

I think all my dungeons were pretty challenging (but fun, because I could illustrate key characters, rooms, passageways, traps, etc., and use the illustrations to hide clues that people had to look for). Back in those days (in high school and at Berkeley) I really only played with people who were hardcore. Nowadays, it’s a different proposition, because the market for gaming is massive, and most of those people are not hardcore. If I were a consultant to Blizzard, for example, I’d recommend making the vast majority of the game accessible to housewives and 12 year olds. Then provide some rabbit holes for people who want something tougher, but I wouldn’t use those people as a starting point. I would start with something beautiful, otherworldly and engaging for the masses. I’d avoid the zombies, go action-adventure as a priority. I myself have been hardcore at points, but in the final equation, bringing joy to the greatest number of people is more rewarding than providing a virtual life for the few. More rewarding personally and spiritually, as well as financially.

Apple II title screen for Tales of the Unknown: Vol. I - The Bard's Tale, as the first game in the series was officially called.

When entering the stables in Bard's Tale I, we are told that the horses have been eaten by monsters. Was it intended at any time during the development of BT1 to implement the purchasing of horses to perhaps exit the city of Skara Brae after Mangar's spell of eternal winter was destroyed? Or was there ever to be any plot or additional dungeons or secret passages involving the stables?

I don’t remember this, no. Everything was pretty much a closed box at the time, the platform was so limited, and there wasn’t an internet, to speak of. BT2 wasn’t a thought in my mind yet, and there wasn’t an obvious way to extend the game (as there would be now, in an online RPG). My guess is that this was just a plot twist or a shortcut so that we didn’t have to come up with a horse animation. BT1 was almost entirely my plot. We had a consultant but his ideas were pretty silly, and we abandoned almost all of them. On BT2 there was some input, as a result of my dungeon editor.

The real-time puzzles called “snares” in Bard’s Tale II are good in concept, but they also seem to be one of the more frustrating parts of the game. How did you come up with the idea for them? Were you happy with the implementation of snares and how they were received?

At the time I thought the snares were awesome, and I don’t remember receiving any negative feedback. But again, I think the playtesting was lacking. It was a few years later that someone told me that they were extremely difficult and frustrating.

My original name-concept for the game was “Shadowsnare,” I had a thought of a number of challenging and visual puzzles (to the limits of what a system could do at that time). Wizardry was just about finding and picking up items. I have always been intrigued by solving puzzles.

My original name-concept for the game was “Shadowsnare,” I had a thought of a number of challenging and visual puzzles (to the limits of what a system could do at that time). Wizardry was just about finding and picking up items. I have always been intrigued by solving puzzles.

Bard’s Tale II also allowed the player to summon monsters to join the group. What inspired that idea?

Just a creative idea that came to me, as best I can remember, in light of the capabilities already in the codebase. I was always trying to think of more magic to incorporate into the game. The idea of having a familiar or some entity that was controlled by magic was an idea from my earlier reading and role playing. The stats for monsters and players were so similar (something obvious to the programmer but not to anyone else), it made perfect sense to do this. I tried to think through everything that could be done, in light of the code, to make the game more interesting. When I was finishing BT1, I already had a lot of new ideas for the next one.

Bard’s Tale I only took place in one town, whereas the second game has six towns as well as a large world to explore. Was that the direction you wanted the series to take from the start? If so, why hadn’t you implemented a larger gameworld in the first game as well?

It didn’t occur to me, my thinking was more dungeon-centric. The idea of any adventure in the outdoors wasn’t really in my conceptual framework then. When I got to BT2, and recognized (with the dungeon editor) I had the capacity to create so many more dungeons with ease, it made sense to also build cities and spread them all out.

Apple II title screen for The Bard's Tale II: The Destiny Knight, the second game in the series - and the last one designed by Michael Cranford. For The Bard's Tale III, Bill "Burger" Heineman took over after Cranford had a falling out with Fargo and left Interplay.

To approach the same question from a different angle, Bard's Tale II was released only about a year after the release of the original Bard's Tale and included quite a few enhancements over the original (huge gameworld, banks, casinos, ranged combat, more spells, real time snares, more monster abilities and monster inventory, etc.). How was so much accomplished in such a small window?

I work very quickly, I always have. I can see programming problems in my head from beginning to end before I even sit down and start typing. On any scale. I don’t generate many bugs in my code, I can visually simulate the performance of code blocks in my mind, and check the output as I go. Then I can do it on a meta level also, for the entire project. I don’t really know how to explain it. I have no difficulty finishing projects as a result. Programming is time consuming but effortless for me, most of the time. It makes it harder to work with other coders on the same application without clear division of labor, because it doesn’t work the same for me with other people’s code. As for the creative concepts in BT2, many of these came to me toward the end of BT1. I probably also had some interaction with Brian Fargo, he always had great ideas. (He and I played D&D together in high school.) But a lot of it was simply knowing what was hard and what was easy, given the codebase. The code I had built made some of these things trivial additions to the game logic.

Personally I loved the level design in the Bard’s Tale games – with all the spinners, anti-magic zones, darkness zones, etc. How did you approach designing the layout of the games’ dungeons, and what are your favorite Bard’s Tale I and/or II levels (if you can recall that)?

I can’t recall anything about the dungeons now, lol. So long ago, and so much code generated since then. But I had built this dungeon editor, which was a top-down maze view of the dungeon level, and you could add walls, puzzles, traps, and monsters anywhere, visually. I am a creative person, it was easy to build the levels with the help of the editor. (Some other people contributed levels to BT2 as well.)

There is a story (I don’t know to what extent it is true) told by “Burger” Heineman as well as by Brian Fargo about how you held the Bard’s Tale floppy disk hostage in order to make Fargo change the terms of the deal between you and Interplay. Could you tell us your side of that story, if you feel like talking about it?

Well, first off, Heineman wouldn’t know anything about it, except perhaps what Brian might have told him. He was a quirky guy who sat in the corner of the office and had no role in the business operation of the company. Everything that happened was between me and Brian; there was no one else ever present.

When I first came to work at Interplay, I already had a game concept and a working prototype that looked like Wizardry. I built it when I was at Berkeley. I was debating if I should even show it to Brian, rather than just going to Brøderbund or EA or Activision on my own. Brian was a high school friend, so I decided to trust him with it, and I showed it to him. He said he could sell it, and we had a vague verbal understanding of what I would receive. I threw out some numbers and he was positive and agreeable. There were no written terms of any kind. I was a young guy without business experience, and Brian was my friend. It never occurred to me that I might be making a mistake.

Late in the development, I realized I had made one. I had a couple nights where I couldn’t get to sleep, I was so anxious. I was not in a position to enforce our verbal understanding, and I realized that I could have easily brought this to EA on my own. It was sold based on the prototype. I had built every part of the game single handedly, with the exception of composing the music. (My friend Larry Holland did that.)

When the game was nearly done (or maybe entirely done, actually; hard to remember now), Brian produced a contract. I do remember asking for it a number of times and feeling like I was being stalled. I had no idea what he was going to put in it. My memory is not spot-on from 28 years ago, so I am only speaking in general terms. If I am getting any part of this out of order, it’s not intentional. The rest of it is accurate.

The contract (in its initial version) offered me a fraction of what I was expecting, and there were some conditions that would limit my earnings. I talked it through with my friend’s dad, who was the CEO of a large civil engineering firm; he thought it was unacceptable, and urged me to hire an attorney. We ended up spending a significant amount of time negotiating, and in the final equation, I think both of us thought the resulting deal was unfair. I have no doubt that Brian was doing what he thought was right, and that he felt that what he offered me was reasonable. There was a lot of emotion at the time, on my part, but he is a good guy and a smart businessman. I have no resentment against him; I’m just frustrated I wasn’t smarter about all this. I heard his rationale in this very clearly at the time, and I understood where he was coming from. If the deal that we agreed on was presented at the beginning of the process, however, I would not have brought this to him at all.

Now, this story that I held a disk hostage to extort someone – that didn’t happen, I would never do that. Sitting on the source code until the deal I was promised was finally put in writing and honored – that is possible. I honestly can’t remember. But again, there was no pressure to change any terms. The deal I ended up accepting was not what I understood I would get, and not what I would have agreed to if I had. I am a person of my word. I didn’t make very much money from these games.

When I first came to work at Interplay, I already had a game concept and a working prototype that looked like Wizardry. I built it when I was at Berkeley. I was debating if I should even show it to Brian, rather than just going to Brøderbund or EA or Activision on my own. Brian was a high school friend, so I decided to trust him with it, and I showed it to him. He said he could sell it, and we had a vague verbal understanding of what I would receive. I threw out some numbers and he was positive and agreeable. There were no written terms of any kind. I was a young guy without business experience, and Brian was my friend. It never occurred to me that I might be making a mistake.

Late in the development, I realized I had made one. I had a couple nights where I couldn’t get to sleep, I was so anxious. I was not in a position to enforce our verbal understanding, and I realized that I could have easily brought this to EA on my own. It was sold based on the prototype. I had built every part of the game single handedly, with the exception of composing the music. (My friend Larry Holland did that.)

When the game was nearly done (or maybe entirely done, actually; hard to remember now), Brian produced a contract. I do remember asking for it a number of times and feeling like I was being stalled. I had no idea what he was going to put in it. My memory is not spot-on from 28 years ago, so I am only speaking in general terms. If I am getting any part of this out of order, it’s not intentional. The rest of it is accurate.

The contract (in its initial version) offered me a fraction of what I was expecting, and there were some conditions that would limit my earnings. I talked it through with my friend’s dad, who was the CEO of a large civil engineering firm; he thought it was unacceptable, and urged me to hire an attorney. We ended up spending a significant amount of time negotiating, and in the final equation, I think both of us thought the resulting deal was unfair. I have no doubt that Brian was doing what he thought was right, and that he felt that what he offered me was reasonable. There was a lot of emotion at the time, on my part, but he is a good guy and a smart businessman. I have no resentment against him; I’m just frustrated I wasn’t smarter about all this. I heard his rationale in this very clearly at the time, and I understood where he was coming from. If the deal that we agreed on was presented at the beginning of the process, however, I would not have brought this to him at all.

Now, this story that I held a disk hostage to extort someone – that didn’t happen, I would never do that. Sitting on the source code until the deal I was promised was finally put in writing and honored – that is possible. I honestly can’t remember. But again, there was no pressure to change any terms. The deal I ended up accepting was not what I understood I would get, and not what I would have agreed to if I had. I am a person of my word. I didn’t make very much money from these games.

In general, how would you describe your experience of working with Interplay and Brian Fargo? What are the moments you remember most and least fondly about it? In hindsight, do you think something could have been done for you to stay at Interplay and further develop the ideas you had in mind for the Bard’s Tale series?

It was mostly great. A great team, led by a guy that I admired and who was a true friend to me through high school. I was doing something that I loved. Hanging with a small, tight band of programmers was fun. We did a lot of things together. Nothing in particular stands out, but I enjoyed the time, until we got to the contract negotiation and negativity that I already mentioned. It was a little personal at the time, but then I grew up and let all that go. Just a lesson in life learned. I didn’t handle my part of all that well.

Brian asked me to leave after Bard’s Tale II, he was not happy with the process we went through to arrive at a deal. He told me he wanted me out for BT3 (which would put me at a lower royalty rate, and the fact was that with the tools and code in hand, they didn’t need me for it). The process also burnt me out, and I wanted to go back to school and do my next project on my own anyway.

There is some regret that we didn’t work things out, and that I didn’t stay to see Interplay grow into what it eventually became. That would have been fun. But I chose another path that was fulfilling.

Brian asked me to leave after Bard’s Tale II, he was not happy with the process we went through to arrive at a deal. He told me he wanted me out for BT3 (which would put me at a lower royalty rate, and the fact was that with the tools and code in hand, they didn’t need me for it). The process also burnt me out, and I wanted to go back to school and do my next project on my own anyway.

There is some regret that we didn’t work things out, and that I didn’t stay to see Interplay grow into what it eventually became. That would have been fun. But I chose another path that was fulfilling.

After Bard’s Tale II, you not only left Interplay, you said you were also disillusioned by the industry as a whole – and so you went back to the university to study philosophy and theology. Could you tell us more about your experience with the industry at the time and what about it made you feel the way you did?

As I mentioned, a story was spread about me, that made me out to be a bad guy. I never heard the whole thing, but when you tell me that someone says I extorted Brian to change the terms in our deal, the picture gets clearer. I also took an unscheduled trip late in the development process for a week and a half (it had been planned for 6 months, but I didn’t bother telling Brian until the contract was signed, as I was not sure we would come to agreement and that it would be relevant). The slander was disheartening for me. I’m a person that values and practices integrity; being characterized this way hurt me. I didn’t want to be part of it anymore, though I did do a deal with Brøderbund, and I worked with some wonderful people there.

Have you played Bard’s Tale III or Dragon Wars? If you have, what are your thoughts on those games? What did you enjoy about them, and what did you not?

I never played them.

Centauri Alliance came in a hexagon-shaped box which included a manual, a field guide, a psionic ability chart and a huge star map.

Could you tell us how you got to work with Brøderbund on Centauri Alliance?

I can’t remember the specifics, but I had a concept for a game similar to Bard’s Tale but much bigger and with a sci-fi theme. I likely made some calls, and they were interested in working with me.

Was it your or Brøderbund’s decision to develop the game exclusively for the Apple II and Commodore 64 platforms (which ultimately contributed to its relative obscurity)? Why didn’t you create an Amiga or DOS version of Centauri Alliance after you were done with the Apple II and C64 ones?

I had never developed for a PC at that point, so it was unknown territory for me. The big problem was that the development got stalled, and by the time it was finally done, the Apple and C64 had started to drop off. It wasn’t like that when the project started, the decline happened quickly. We may have discussed a Dos version, I don’t remember.

You say the Centauri Alliance development got stalled. Why did that happen?

There was a huge delay having the artist handle the animation. The way we did it, back then, was basically like a slide show; the animation required subtle changes to be made in a series. And the game was so big, that meant a ton of art. I think their resources were limited, and there were higher priority projects. Plus, I made the game too big anyway. So there was a very long wait for the artwork.

The “RPG side” of Brøderbund, and the company’s history at the time of Centauri Alliance's release, remains relatively little known to this day. Coud you tell us more about the people you interacted with at Brøderbund, and what you enjoyed (or didn’t enjoy) about the company culture and atmosphere there at the time? How supportive were they about your project?

Goodness, I cannot remember their names. They were terrific people. One guy in particular was in my area a lot, and was a real friend during the process. I don’t know that I was up there more than one time during the development, so I didn’t have a sense of the company’s commitment to RPG. They seemed very supportive, but there were production delays around getting the graphics/animation done that stalled the project by almost a year, I recall. They told me they were working on something called Carmen San Diego. : )

Centauri Alliance's combat screen as seen on the C64. Combat areas in the game differ in size; black squares are obstacles that cannot be crossed.

In Centauri Alliance, you went from the Bard's Tale-style combat to a hex grid, introducing a unique compromise between the first person menu-based combat and the full-blown tactical isometric combat characteristic of e.g. the Goldbox games - your party moved around on the hex grid but was only represented by a single sprite. What motivated that design decision, and why didn't you go for a Goldbox-like combat?

It was simply a code compromise. There needed to be a spatial dimension to combat; having a list of characters like in BT (with 3 on the front line to take physical damage) was too simplistic. I went with a compromise that was still simplistic. If there had been a SQL it would have evolved further.

For Centauri Alliance, you created a huge sci-fi universe with unique races. What were your inspirations for the game's setting? How did you approach designing the psionic abilities - and in particular, what motivated you to introduce the shape-changing ("metamorph") skills exclusive to the Praktor race?

I was an avid sci-fi reader. I can’t pinpoint where my influences were. Shape changing was something characteristic of characters in a number of books, and again, it was something that made sense in light of the code, to permit “magical” enhancements. I can’t remember much else leading to this. I obviously think in narrative. I have a sci-fi book partly written, in fact. No connection to Centauri Alliance. : )

Can you tell us more about the sci-fi book you're working on?

The book is set a few hundred years from now. It deals with a certain mutation or punctuated evolutionary turn that humans have taken which allows them to survive and fight back against a race that came here to take over and transform our planet. But the evolutionary turn happened decades before the aliens arrived, which allowed a generation of our species to survive. But that raises a question of how such a thing could have happened, in advance of the threat. There’s a smaller story of specific people in the broader tale, of course. That’s the broad strokes, wait for the book. And hopefully the movie. : )

"This could turn into the next big science fiction series," said the 1990 QuestBusters review of Centauri Alliance. Were the first game's sales too poor for Brøderbund to be interested in turning it into a series? Did you have plans for Centauri Alliance II, and if so, what can you recall about them?

This is probably the case, that the release on two platforms that were dropping out probably made this a disappointment. I don’t remember making money on it. If I had been up to speed on PC development, I might have been able to turn this in a direction that would have led to a second version. But hard to build a second if everyone running Dos never saw the first.

Despite the mixed reviews that Bard’s Tale II’s real-time snares received, you also added timed puzzles to Centauri Alliance (such as running through a maze to shut down the reactor before it explodes). Do you believe real-time elements can add something to a turn-based RPG?

Absolutely. I mean, my goal was always to simulate real-time. I just didn’t have a way to do it, or a vision for it, given the limitations of the platforms I was developing on. If I had stayed with this, I would have ultimately developed something like the big MMORPGs.

Speaking of real-time elements, why were random encounters in BT1 and BT2 checked in real time instead of each time you moved or turned? Sometimes you would end up with multiple battles in the same square since you didn't even have time to distribute new loot before being beset by a new monster group.

Hmm, I don’t remember the exact rationale. Again, though, I wanted to simulate reality. There was obviously a need for some tuning on this, though!

Do you have any thoughts on the ongoing "oldschool" RPG revival fueled by Kickstarter projects like Project Eternity or Wasteland 2 and indie titles like Legend of Grimrock? Even a major publisher like Ubisoft is now designing Might and Magic X as a grid- and turn-based first-person RPG in the vein of World of Xeen. Why do you think oldschool RPGs are making a comeback?

There is an aspect of it that the typical first-person shooter games can’t capture. Something like WoW has done a good job bringing strategic elements into gameplay, but the ability to sit and think and plan really does meet a different need than blowing things up that run at you.

Ultima 1 went to Ultima 9, Wizardry went from 1 to 8, and even Might and Magic has a number 10 in the works. Bard's Tale stopped at 3, but where do you think the Bard's Tale series would be if it had continued to this day and if you were still working on it? What are the main things you would change about the series' design today compared to that of the original Bard’s Tale games?

If it had been under my control, it would have had new versions and new worlds, and would have evolved and, I think, become an MMORPG. I’ve been doing internet application development now for many years, I might have been first to market on the concept, if I hadn’t walked away from game development. I can’t comment on the design in hindsight, it was the best we could do at the time. If I’d been on version 3 and later, it would have gotten even better.

Do you happen to have any plans for remakes or Kickstarter projects? Generally, do you see yourself working in video games again?

I’m open to it. I’m so busy doing other kinds of development, I haven’t been keeping up or determining where I can play a part. If someone out there has a suggestion, shoot me an email.

Thank you for your time.

Special thanks go to the people who submitted their questions for this interview! Your contribution was much appreciated.

If you enjoyed this interview, be sure to check out the other ones in our retrospective interview series.