- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 99,616

Tags: Fallen Gods; Mark Yohalem; Wormwood Studios

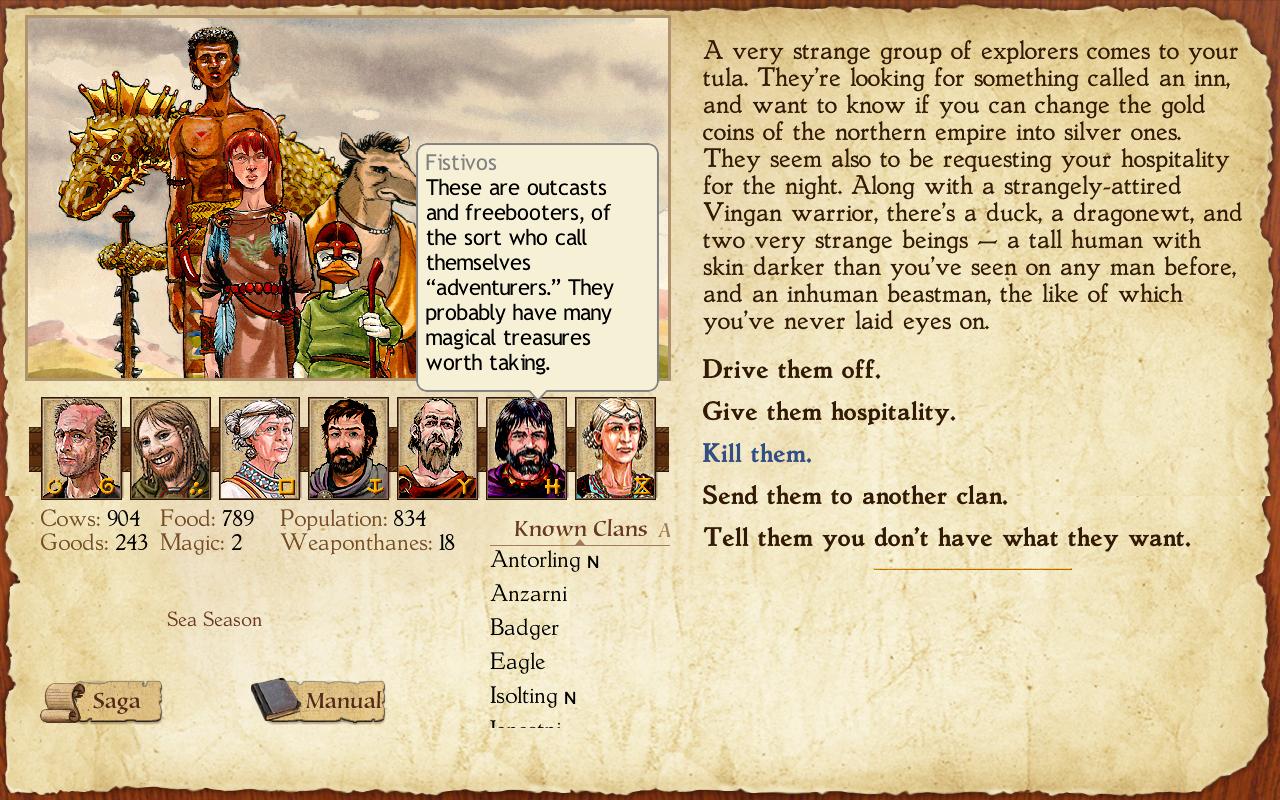

These Fallen Gods development updates are becoming more and more detailed. This month's update offers a comprehensive look at the eight character types who can become part of the player's warband, from the lowly churl to the powerful witch. Each description includes an animated image of the character, a sample of text from one of the game's events that involve the character, and details on where the character can be found, how the character can help you, and what it'll cost you to acquire and keep the character around. It's easily the longest update yet, so I'll just quote the framing text here:

A major part of Fallen Gods is winning men and women to your side in your struggle to clamber back to the Cloudlands. While few mortals are a match for a god, having their help means that you will not need to fight your foes alone, and their skills may mean the difference between overcoming an obstacle and being stymied in your quest.

These “followers,” who together compose the god’s “warband,” are important thematically as well. While Norse sagas often focus on a single heroic figure, that hero is frequently defined by his relationship to his friends, family, and dependents. Thus, at the very outset,Beowulf’s skald tells us a young prince must “give[] freely while his father lives / so that afterwards in age when fighting starts / steadfast companions will stand beside him / and hold the line.” (Heaney Trans.) Interestingly, Beowulf ends with most of the king’s men running away from him, breaking the line, in his battle against the dragon. But even then, it is both thematically and tactically necessary for young Wiglaf to be there at his side to soften up the great dragon for Beowulf’s killing stroke.

There are sagas in which the protagonist is alone, but this is typically an abysmal and unusual situation—for instance, a consequence of being outlawed and cut off from human society, as in Grettir’s Saga or Egil’s Saga. The ordinary structure of these stories, reflecting the structure of the society from which they arose, is that a hero may outstrip other men and women, but he benefits from their wisdom, their rebukes, their shields, and ultimately their companionship. And from a narrative standpoint, they offer a chance for the hero to show his strengths and weaknesses in how he heeds or ignores that wisdom, bows to or refutes those rebukes, stirs or shakes the fighters who hold those shields, and wins or loses the hearts of those companions.

So too in Fallen Gods. Unlike many RPGs that make companions’ own goals, undertakings, personalities, and problems the focus of the narrative, Fallen Gods remains tightly focused on its titular protagonist. But unlike RPGs where companions are absolute non-entities, or where the hero has no companions at all, Fallen Gods uses followers as a means of enriching the god’s character and enhancing the player’s options. They will offer suggestions and reactions during events, and the player will be able to ask them to undertake tasks suited to their special skills. While followers do not have individual personalities, their sharply distinct classes (churls, woodsmen, fighters, priests, berserks, skalds, maidens, and witches) make them stand out from each other narratively, while also offering different strategic benefits at different costs.

Before going into detail about each class, it may be helpful to provide a framework for what kind of costs and benefits followers may present.

First, a follower must be located and persuaded to join the warband. Traveling to a location where the follower can be found (like a shrine or stronghold) can take days, and time is the player’s only irreplaceable resource. Once the player reaches the necessary location, the follower must be recruited. Some followers, like churls, will ask nothing; others, like fighters, will want gold; and yet others, like witches, will demand a much higher price.

Except for those that are “sworn,” a rare minority, followers must be kept happy or they will leave the warband. This requires feeding them every day; hunger eats the bonds of loyalty. Food costs either gold (if bought in town) or time (if gotten by hunting). The more followers you have (the warband can include up to five), the more food you need. Followers will also grow unhappy (and weakened) by status ailments such as being crippled (which halves might), cursed (which harms luck), or sick (which drains HP).

But even a healthy, well-fed follower will grow unhappy if the god errs. Few are fond of a god who flees or fails. And even success can be a matter of taste—the same wise restraint that impresses a priest may disgust a berserk, for instance. The player can gladden (and sometimes strengthen) a follower with the gift of an item, whether a lesser thing like a golden arm-ring or a great treasure such as Firebrand. But a gifted item is gone for good; the god can never get it back. Rest or a skald’s song can sometimes soothe the warband’s spirits, but the day thus lost cannot be regained, either.

Assuming the player can find and keep a warband, however, he gains an important edge inside and outside of combat. In battle, even a powerful god can be overwhelmed when faced with multiple foes. Followers are necessary to even the odds and prevent the god from being flanked or surrounded. And some followers, such as berserks, can do much more than merely soak up blows that would otherwise land upon the god: they can deal out death as well as their leader. Moreover, certain followers can help against certain types of foes (such as woodsmen against wolves) given their knowledge and skill.

Outside of battle, followers’ might and craft can provide the god with both generic benefits (such as the ability of a skald to raise morale, mentioned above) and special options inside of events. While events focus primarily on the god, his skills, and his choices, followers open paths in the choose-your-adventure-style events that otherwise would be unavailable—a maiden might be traded for a wurm’s wisdom; a witch might swindle dead men of their strength; a berserk might hoist a boulder too heavy for the god to lift; a priest might offer an old law to put a bitter feud to rest.

In these ways, assembling a warband is both fun in itself and a critical strategic layer of the game. The player’s job is to plot a path to victory and decide what costs can (and must) be borne to make that path possible. To be sure, luck and experience both have a role to play alongside pure reason, but there is no single combination necessary for victory: Fallen Gods is about exploration, and the dynamics and possibilities unlocked by different followers is one of the things the player is encouraged to explore.

[...] Winning in Fallen Gods, or even just exploring its maze of paths and uncovering its secrets, will require assembling the right warband for particular challenges ahead. Such strategy will involve a mix of common sense (e.g., adding a woodsman before exploring a vast forest), in-game information gathering (e.g., finding out about a cave before attempting to delve its depths), and specific experience (e.g., knowing from having encountered certain events before that a certain follower would be helpful). As the player learns about the game’s lore and rules, he’ll become better at that kind of strategizing.

But Fallen Gods is different from more punishing rogue-likes that require the perfect combination of tools (and luck) to win. Our focus is more on ensuring thatevery combination of followers (and god skills and items) yields new and interesting opportunities for the player to engage with the game and make satisfying choices. You may not win every time, but our hope is that some new path will open or some new wrinkle will be found on an old path, such as a priest’s forlorn commentary on a witch’s misdeed, or a berserk’s catastrophic rush to battle that spoils a well-laid ambush. By wrangling with this cast of characters, the god—and, more importantly, the player who controls the god—will be able to show himself as not only a hero but a leader, for better and worse.

As usual, the update also includes a sample from the game's soundtrack - a particularly nice one this time, in my opinion. Next month's update sounds like it's going to be about event design.

These Fallen Gods development updates are becoming more and more detailed. This month's update offers a comprehensive look at the eight character types who can become part of the player's warband, from the lowly churl to the powerful witch. Each description includes an animated image of the character, a sample of text from one of the game's events that involve the character, and details on where the character can be found, how the character can help you, and what it'll cost you to acquire and keep the character around. It's easily the longest update yet, so I'll just quote the framing text here:

A major part of Fallen Gods is winning men and women to your side in your struggle to clamber back to the Cloudlands. While few mortals are a match for a god, having their help means that you will not need to fight your foes alone, and their skills may mean the difference between overcoming an obstacle and being stymied in your quest.

These “followers,” who together compose the god’s “warband,” are important thematically as well. While Norse sagas often focus on a single heroic figure, that hero is frequently defined by his relationship to his friends, family, and dependents. Thus, at the very outset,Beowulf’s skald tells us a young prince must “give[] freely while his father lives / so that afterwards in age when fighting starts / steadfast companions will stand beside him / and hold the line.” (Heaney Trans.) Interestingly, Beowulf ends with most of the king’s men running away from him, breaking the line, in his battle against the dragon. But even then, it is both thematically and tactically necessary for young Wiglaf to be there at his side to soften up the great dragon for Beowulf’s killing stroke.

There are sagas in which the protagonist is alone, but this is typically an abysmal and unusual situation—for instance, a consequence of being outlawed and cut off from human society, as in Grettir’s Saga or Egil’s Saga. The ordinary structure of these stories, reflecting the structure of the society from which they arose, is that a hero may outstrip other men and women, but he benefits from their wisdom, their rebukes, their shields, and ultimately their companionship. And from a narrative standpoint, they offer a chance for the hero to show his strengths and weaknesses in how he heeds or ignores that wisdom, bows to or refutes those rebukes, stirs or shakes the fighters who hold those shields, and wins or loses the hearts of those companions.

So too in Fallen Gods. Unlike many RPGs that make companions’ own goals, undertakings, personalities, and problems the focus of the narrative, Fallen Gods remains tightly focused on its titular protagonist. But unlike RPGs where companions are absolute non-entities, or where the hero has no companions at all, Fallen Gods uses followers as a means of enriching the god’s character and enhancing the player’s options. They will offer suggestions and reactions during events, and the player will be able to ask them to undertake tasks suited to their special skills. While followers do not have individual personalities, their sharply distinct classes (churls, woodsmen, fighters, priests, berserks, skalds, maidens, and witches) make them stand out from each other narratively, while also offering different strategic benefits at different costs.

Before going into detail about each class, it may be helpful to provide a framework for what kind of costs and benefits followers may present.

First, a follower must be located and persuaded to join the warband. Traveling to a location where the follower can be found (like a shrine or stronghold) can take days, and time is the player’s only irreplaceable resource. Once the player reaches the necessary location, the follower must be recruited. Some followers, like churls, will ask nothing; others, like fighters, will want gold; and yet others, like witches, will demand a much higher price.

Except for those that are “sworn,” a rare minority, followers must be kept happy or they will leave the warband. This requires feeding them every day; hunger eats the bonds of loyalty. Food costs either gold (if bought in town) or time (if gotten by hunting). The more followers you have (the warband can include up to five), the more food you need. Followers will also grow unhappy (and weakened) by status ailments such as being crippled (which halves might), cursed (which harms luck), or sick (which drains HP).

But even a healthy, well-fed follower will grow unhappy if the god errs. Few are fond of a god who flees or fails. And even success can be a matter of taste—the same wise restraint that impresses a priest may disgust a berserk, for instance. The player can gladden (and sometimes strengthen) a follower with the gift of an item, whether a lesser thing like a golden arm-ring or a great treasure such as Firebrand. But a gifted item is gone for good; the god can never get it back. Rest or a skald’s song can sometimes soothe the warband’s spirits, but the day thus lost cannot be regained, either.

Assuming the player can find and keep a warband, however, he gains an important edge inside and outside of combat. In battle, even a powerful god can be overwhelmed when faced with multiple foes. Followers are necessary to even the odds and prevent the god from being flanked or surrounded. And some followers, such as berserks, can do much more than merely soak up blows that would otherwise land upon the god: they can deal out death as well as their leader. Moreover, certain followers can help against certain types of foes (such as woodsmen against wolves) given their knowledge and skill.

Outside of battle, followers’ might and craft can provide the god with both generic benefits (such as the ability of a skald to raise morale, mentioned above) and special options inside of events. While events focus primarily on the god, his skills, and his choices, followers open paths in the choose-your-adventure-style events that otherwise would be unavailable—a maiden might be traded for a wurm’s wisdom; a witch might swindle dead men of their strength; a berserk might hoist a boulder too heavy for the god to lift; a priest might offer an old law to put a bitter feud to rest.

In these ways, assembling a warband is both fun in itself and a critical strategic layer of the game. The player’s job is to plot a path to victory and decide what costs can (and must) be borne to make that path possible. To be sure, luck and experience both have a role to play alongside pure reason, but there is no single combination necessary for victory: Fallen Gods is about exploration, and the dynamics and possibilities unlocked by different followers is one of the things the player is encouraged to explore.

[...] Winning in Fallen Gods, or even just exploring its maze of paths and uncovering its secrets, will require assembling the right warband for particular challenges ahead. Such strategy will involve a mix of common sense (e.g., adding a woodsman before exploring a vast forest), in-game information gathering (e.g., finding out about a cave before attempting to delve its depths), and specific experience (e.g., knowing from having encountered certain events before that a certain follower would be helpful). As the player learns about the game’s lore and rules, he’ll become better at that kind of strategizing.

But Fallen Gods is different from more punishing rogue-likes that require the perfect combination of tools (and luck) to win. Our focus is more on ensuring thatevery combination of followers (and god skills and items) yields new and interesting opportunities for the player to engage with the game and make satisfying choices. You may not win every time, but our hope is that some new path will open or some new wrinkle will be found on an old path, such as a priest’s forlorn commentary on a witch’s misdeed, or a berserk’s catastrophic rush to battle that spoils a well-laid ambush. By wrangling with this cast of characters, the god—and, more importantly, the player who controls the god—will be able to show himself as not only a hero but a leader, for better and worse.

![Glory to Codexia! [2012] Codex 2012](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_slushfund2012.png)