- Joined

- Apr 24, 2015

- Messages

- 20,912

http://burdenofcommand.com/the-heart-of-war

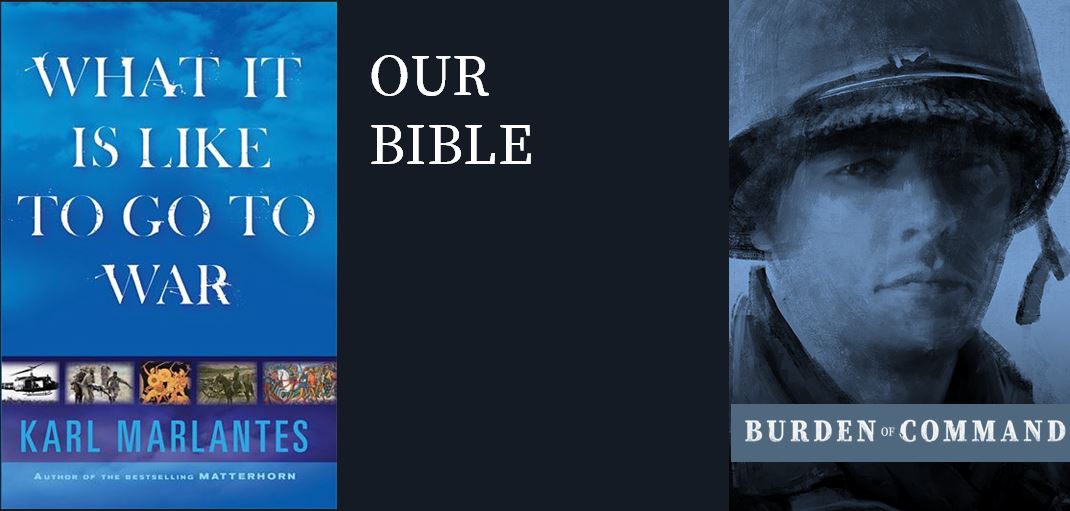

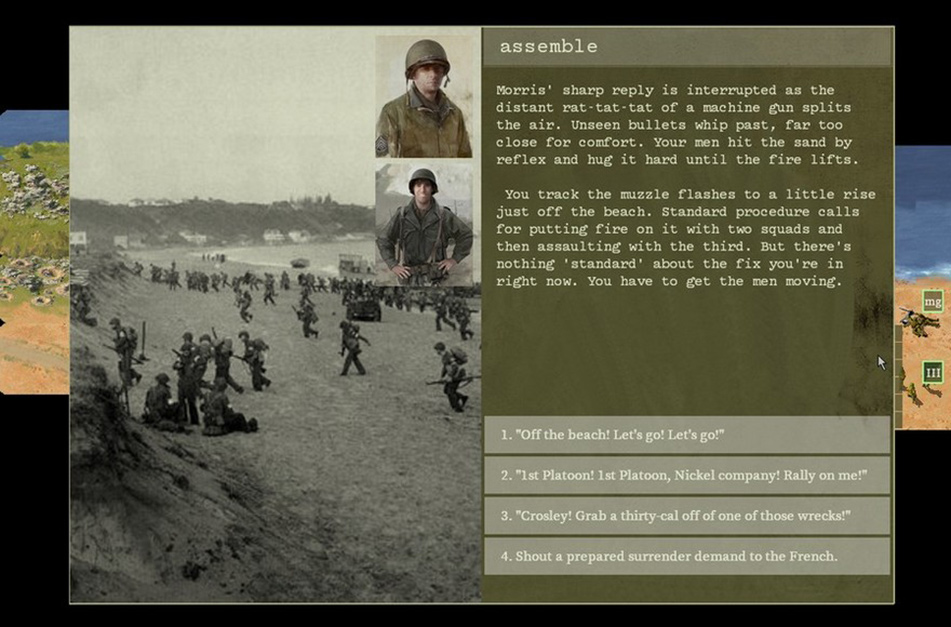

Many engaging games have war’s trappings but do they have its heart? For example, In Call of Duty, the battlefield is visceral and your squad mates human. But with its near instant restarts, your death is only an inconvenience. Given the high rate at which you personally off endless enemies, their deaths soon become a simple power trip. In other games, your generalship but not your humanity is tested as you dispatch historically accurate “units” at an abstract distance.

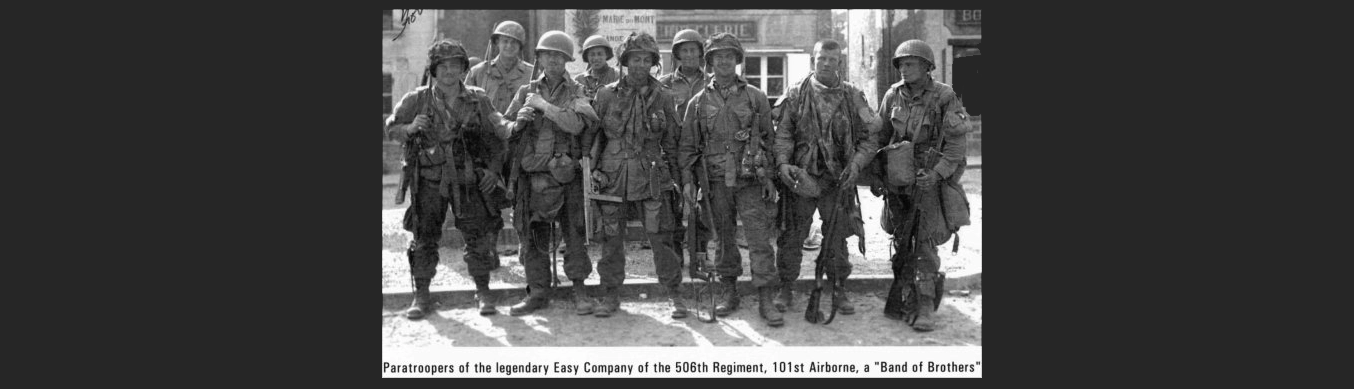

In Burden of Command, as in Band of Brothers or This War of Mine, death is not an inconvenience, not a power trip, but a burden.

Men fear death. This dev blog is about the mechanics of how you’ll overcome that fear to provide leadership on an emotionally authentic battlefield.

Death Here is Thy Victory

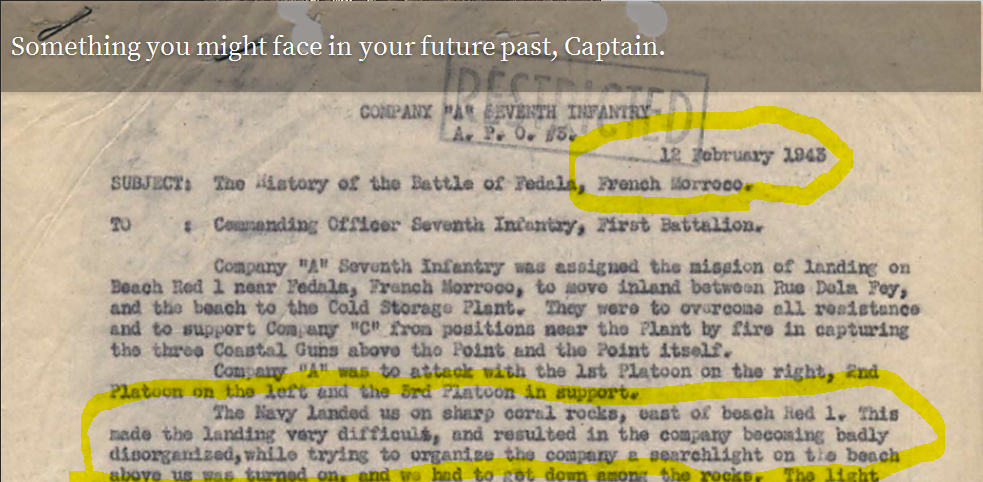

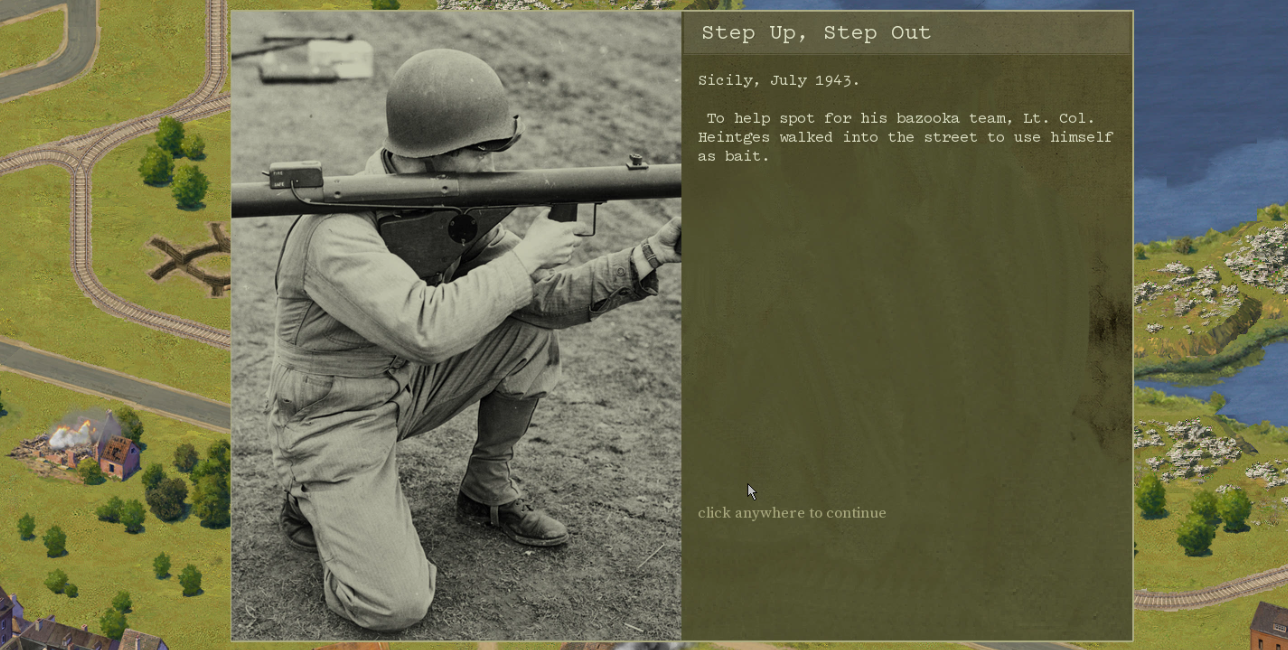

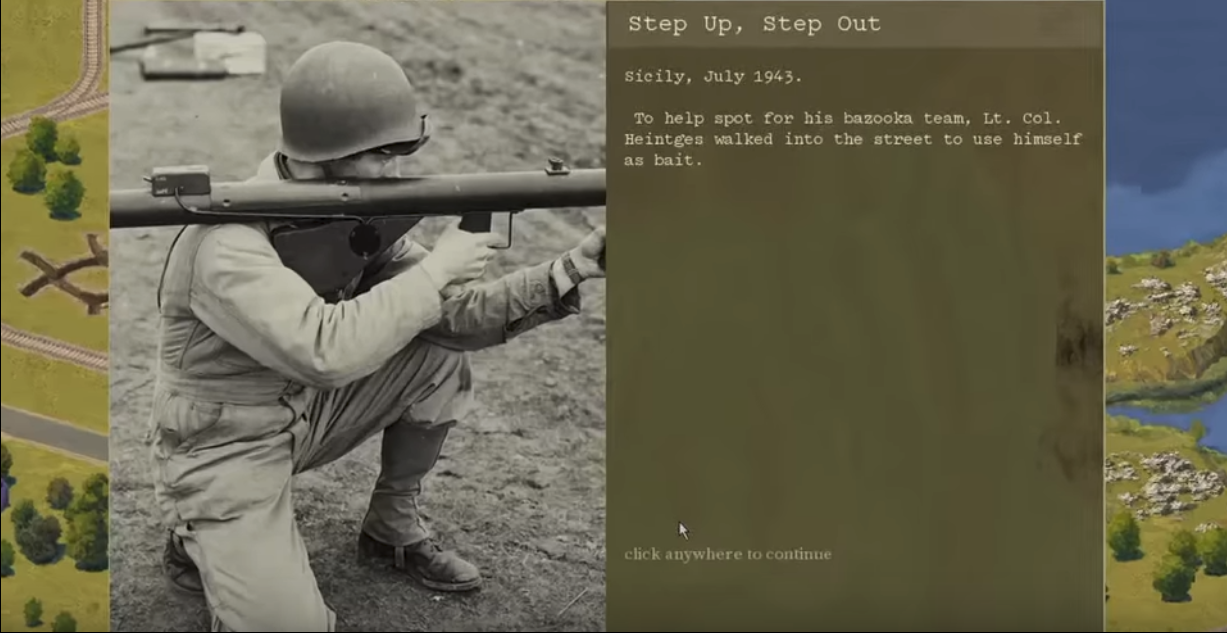

Step into the open unprepared in Burden of Command and you and your men will swiftly become casualties. Burden of Command features Permadeath. When men die they stay dead. Their lives are your burden. There is no “plot armor“ for your young lieutenants.

Learn the Art of Suppression

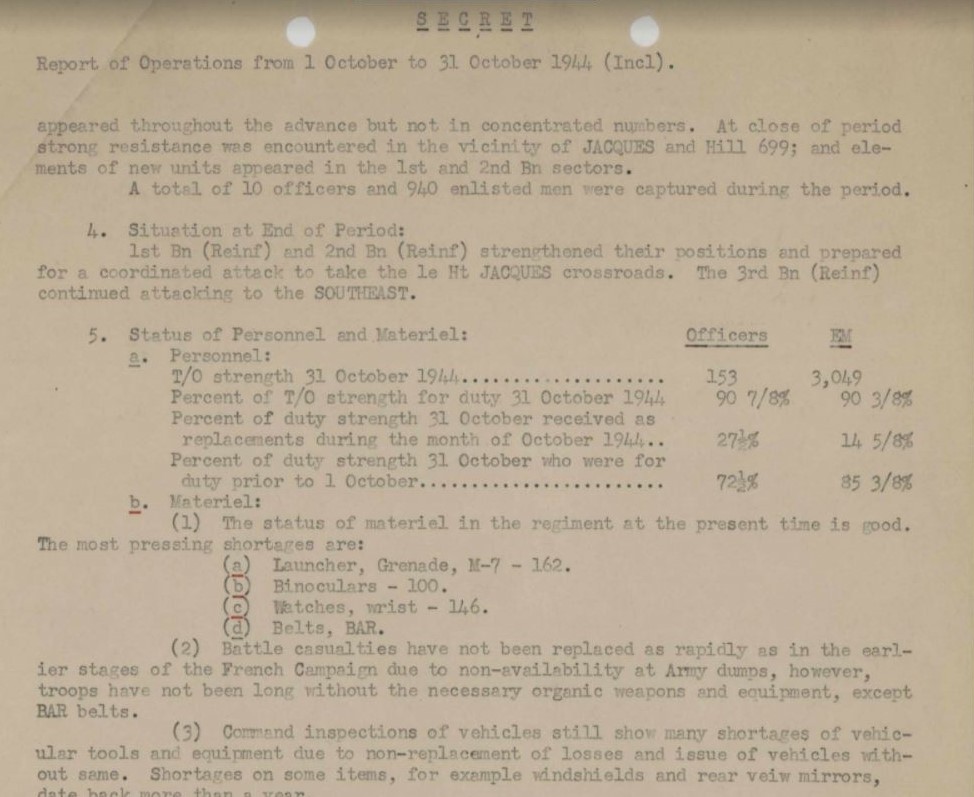

To keep your men alive you must first learn to suppress the enemy. Unlike many games, tactical success is not about marksmanship, it is about fear. Because men fear death they take cover when bullets fly. As a consequence, casualties from small arms fire are low. In WWII approximately 8000 bullets were fired per casualty inflicted. In addition, when men take cover their own marksmanship drops dramatically (it’s hard to aim when you’re fearing for your life).

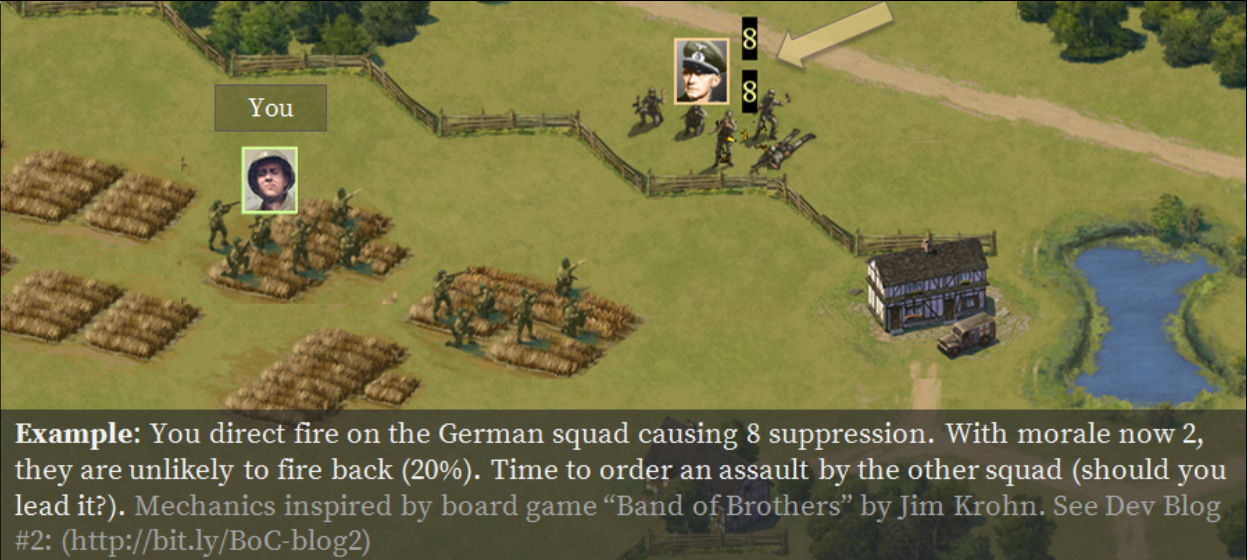

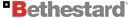

In Burden of Command the fear of death is represented by Morale. High Morale units do as commanded. Like firing at the enemy.

Low Morale units do not. A squad with ten Morale has a 100% chance of doing what you order. A squad with five Morale has a 50% chance, a squad with one Morale, a 10% chance, and so forth. Firing at the enemy lowers their Morale. This effect is called Suppression.

Your goal as a battlefield commander is to maintain your unit’s Morale while suppressing the enemy. On real battlefields firing goes up when the ‘boss’ is near. Similarly, in Burden of Command, you and your subordinate leaders’ Command Presence (stacking a leader with a unit) increases Morale. Further you can Rally men (which removes suppression) as well as Direct Fire to increase Suppression on the enemy.

However, unlike many other games, even those with Morale, Suppression does not cause units to surrender or rout. Imagine seeing a stream of machine gun fire going over your head. Would you stand up in the face of it to surrender or run? Chances are, you wouldn’t, and most soldiers wouldn’t either.

To get the enemy to surrender you are going to have to close with them and assault.

“Fear of the Bayonet”

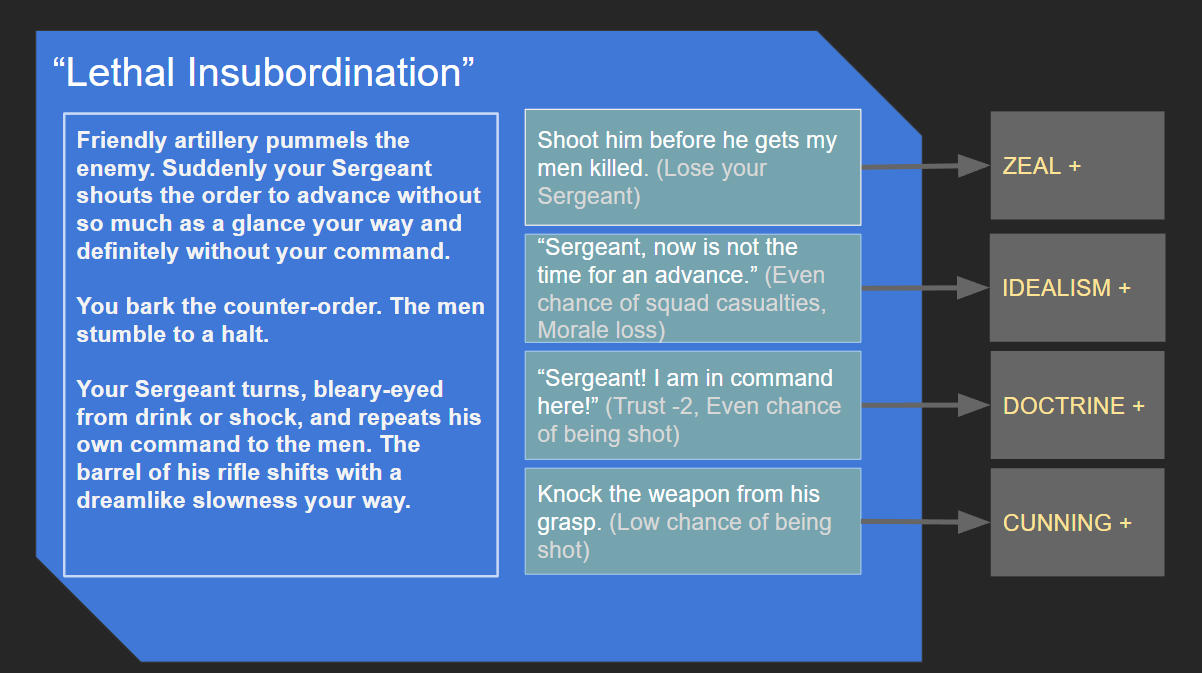

Only psychopaths want to fight hand to hand. In his fine book Brains and Bullets Leo Murray estimates that left to their own devices fewer than 20% of soldiers are willing to commit to a hand to hand assault. It will be your burden as a leader to motivate that other 80% into finishing the job.

Win Hearts: Trust

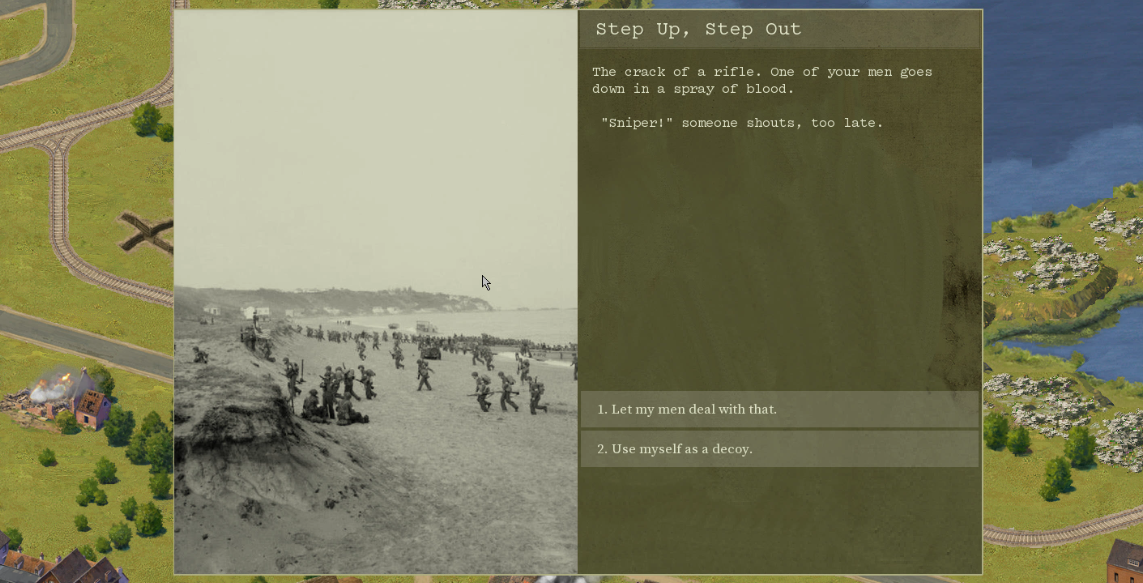

In Burden of Command the effect of your morale improving actions like Rallying, and Command Presence will be based on your men’s Trust in you. How do your build your Trust stat? By taking risks with the men. Every time you put your own life on the line alongside them, they take note, and your Trust increases. Of course, doing so means risking Suppression, wounds, or even death. It’s a tradeoff.

If you have gained Trust and lead the assault your Command Presence will make it more likely to happen. According to Brains and Bullets a “low authority” (Trust) leader can double the chance that those under his command will follow him in an assault. A “high authority” leader can more than triple that chance. Will you take the risks needed to earn that level of Trust?

Lead by Example

Trust is not always enough to get men to take terrifying actions like engaging in hand to hand combat. Sometimes you must lead by example. I recall once being at the scene of a bloody bike accident. Everyone froze, implicitly looking to someone else to take action, to lead the way. This common phenomenon is known as ‘diffusion of responsibility‘. However, once someone finally did take action, everyone swiftly joined in. This is “leading by example.”

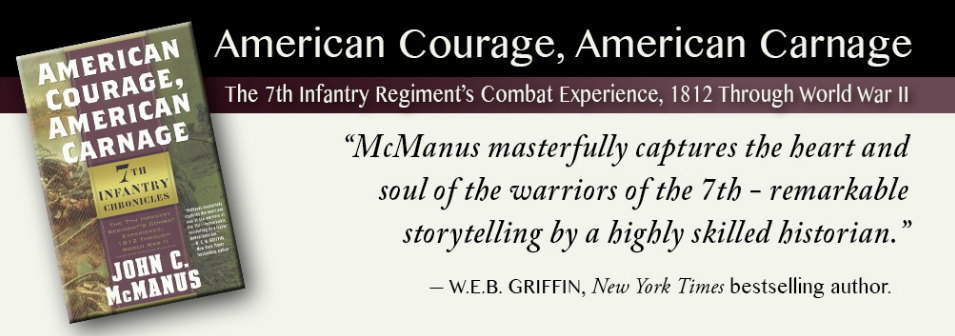

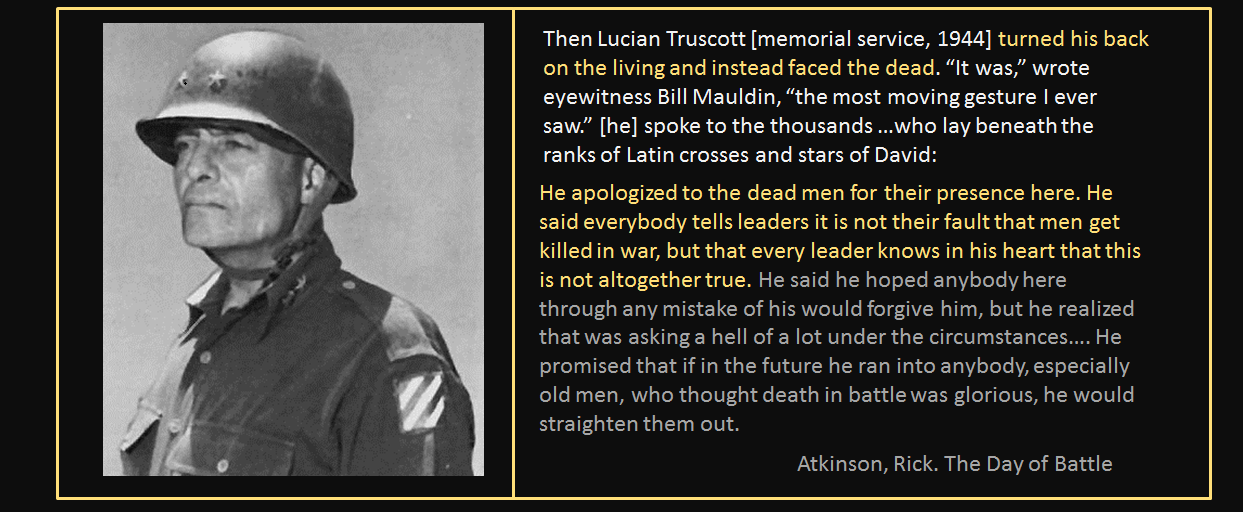

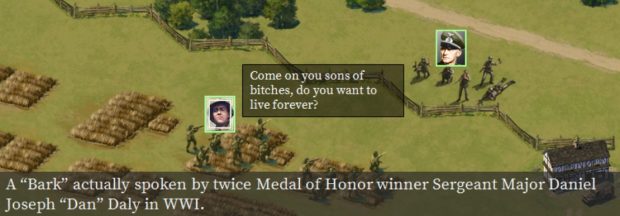

In his book on Omaha Beach on D-Day, our advising and playtesting historian John McManus describes how Colonel Taylor stood up under truly withering fire and shouted to the prostate soldiers around him “There are two kinds of men out here! The Dead! And those about to die! So let’s get the hell off this beach.”

You may remember that quote from the film The Longest Day, or how Captain Winters in Band of Brothers stood upright under machine gun fire, kicking soldiers in the rear and urging them up to assault. Their real life examples raised morale and led to victory.

In Burden of Command this is represented by a special leader action called Grandstanding. It can get Suppressed units back on their feet for the assault. But in doing so, you may risk losing Trust, becoming suppressed, or even killed…

Your Heart

We’ve discussed how you can take on the Burden of Command by leading through Rallying, Command Presence, and Trust. How you can overcome the dark heart of battle: the fear of death. But unless we create empathy, we will fail to make you personally feel the fear of death for your men, the emotionally personal Burden of Command.

We want to make you hesitate to order that assault, not because you fear losing a powerful “game unit,” but because you don’t want to lose Lieutenant Dearborn.

Next time we’ll focus on the artistic, narrative, and historical devices we use to create that empathy. The second part of the emotionally authentic experience that is Burden of Command.

![Lost%20Patrol,%20The%20(1990)(Ocean)(Disk%201%20of%202)[cr%20HZ][t%20+16%20HZ]_010.png](http://www.classicamiga.com/images/stories/jreviews/games/L/Lost%20Patrol,%20The%20(1990)(Ocean)(Disk%201%20of%202)[cr%20HZ][t%20+16%20HZ]_010.png)

![Glory to Codexia! [2012] Codex 2012](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_slushfund2012.png)