-

Welcome to rpgcodex.net, a site dedicated to discussing computer based role-playing games in a free and open fashion. We're less strict than other forums, but please refer to the rules.

"This message is awaiting moderator approval": All new users must pass through our moderation queue before they will be able to post normally. Until your account has "passed" your posts will only be visible to yourself (and moderators) until they are approved. Give us a week to get around to approving / deleting / ignoring your mundane opinion on crap before hassling us about it. Once you have passed the moderation period (think of it as a test), you will be able to post normally, just like all the other retards.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Deus Ex Deus Ex 20th Anniversary - at least we get a remix album

NPC451

Literate

- Joined

- Jun 20, 2020

- Messages

- 46

grimace

Arcane

- Joined

- Jan 17, 2015

- Messages

- 2,116

I absolutely agree. The thematic elements are drowned out by the new instrumentation.

re: 01.Alexander Brandon, Michiel van den Bos - Alexander Brandon - So It Begins (Deus Ex Main Title)

The brassy bombastic bits were smoothed with some aggressive sand papering. The new remixes are aerodynamic and fly immediately past my ears.

The result is unremarkable futuristic elevator music.

grimace

Arcane

- Joined

- Jan 17, 2015

- Messages

- 2,116

1

Deus Ex: Main title theme PC Version (HQ)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7w3bgRdlanI

2

Deus Ex Soundtrack #Bonus- 'Deus Ex' (Orchestrated)

This rendition of the main theme was recorded with a live orchestra for the PS2 version, Deus Ex: The Conspiracy.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0H2v9TRESjQ

3

Conspiravision: Deus Ex Remixed: 01: So It Begins (Deus Ex Main Title)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G5YdnLKkg2U

4

Bonus: Fan Made

Tigran Papazyan Deus Ex - Main Theme (2019 OST Remake)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2m8THegimRI

Someone could make a poll with these options for favourite version of the Title Theme.

Deus Ex: Main title theme PC Version (HQ)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7w3bgRdlanI

2

Deus Ex Soundtrack #Bonus- 'Deus Ex' (Orchestrated)

This rendition of the main theme was recorded with a live orchestra for the PS2 version, Deus Ex: The Conspiracy.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0H2v9TRESjQ

3

Conspiravision: Deus Ex Remixed: 01: So It Begins (Deus Ex Main Title)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G5YdnLKkg2U

4

Bonus: Fan Made

Tigran Papazyan Deus Ex - Main Theme (2019 OST Remake)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2m8THegimRI

Someone could make a poll with these options for favourite version of the Title Theme.

AW8

Arcane

Some of the remixes are so different from the original that you can't even hear that it's a remix. The Paris Dance one is probably the worst of the ones I listened to, I can't even figure out which of the Paris Club tracks it's supposed to be a remix of. I checked the Hong Kong Club tracks as well to see if it was simply mis-named, but couldn't hear any similarity. It sounds like a random drum and bass song.

I like the NYC Streets remix, but overall, these remixes are unfortunately what the Special Edition is to Star Wars.

I like the NYC Streets remix, but overall, these remixes are unfortunately what the Special Edition is to Star Wars.

AureliusMMXII

Educated

LESS T_T

Arcane

- Joined

- Oct 5, 2012

- Messages

- 13,582

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)

How about that. The Nameless Mod retrospective: https://techraptor.net/gaming/features/deus-ex-20th-anniversary-nameless-mod-retrospective

Deus Ex 20th Anniversary: The Nameless Mod Retrospective

The 7-Year Journey to Create Forum City

If a game came out today that depicted a world ravaged by a viral outbreak, dehumanized by capitalism, in the throes of mass public riots, gripped by anti-government sentiment, and witnessing the progressive breakdown of American society amid the rise of China as an autonomous superpower, you might think it was too on-the-nose. Twenty years ago however, it was simply the setting of a radical, and somewhat prophetic video game, called Deus Ex.

Directed by System Shock producer Warren Spector and designed by future Dishonored creative director Harvey Smith, Deus Ex represented a profound leap in both storytelling and mechanical depth for first-person video games. The game placed players in the role of J.C. Denton, a cybernetically augmented United Nations Anti-Terrorism agent who gradually unravels a web of conspiracies gripping the dark cyberpunk future of 2052. Its sprawling world was dense with philosophical questions, conflicted morality, deep characters, and all the ingredients that make an instant classic; its character customization system and resulting player freedom is still imitated today.

It’s success spawned a lukewarm sequel in 2003 with Invisible War, and then a successful revival in 2011 with the prequel Human Revolution and its own sequel in 2016, Mankind Divided. The original game is fondly remembered in PC gaming communities with the meme, “every time you mention it, someone will install it.”

The game’s 20th anniversary lands on June 22, and there are almost as many ways to celebrate its legacy as there are ways to play the game itself. While it resonates today possibly more than it did in 2000—and it’s available on Steam—we wanted to celebrate by taking a look at one of the game’s most overlooked achievements. Seven years after its release, Deus Ex served as the basis for one of the most impressive mods of its generation, known only as The Nameless Mod.

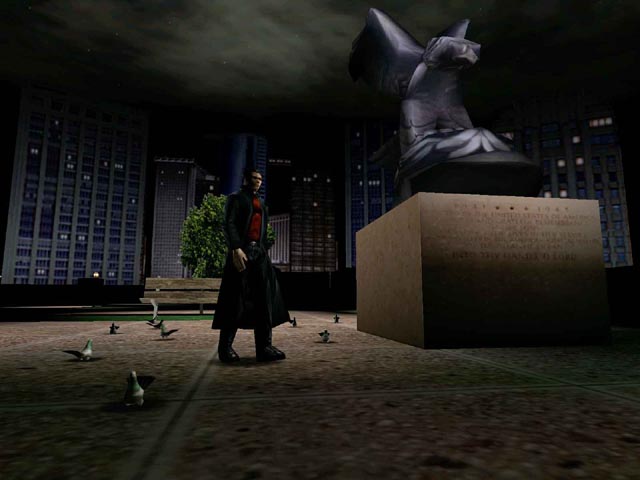

The original Deus Ex

The Origins of Deus Ex’s The Nameless Mod

Getting into games has always been hard, but in 2000, the tools available to beginners were either very expensive, or simply not available. Easily moddable games were often the best way to cut one’s teeth in game development, and Deus Ex had an active mod scene. Mods could range from being small texture or weapon packs, to larger mission packs and beyond. The Nameless Mod represented the largest and most complex kind of mod, known as a total conversion. A total conversion uses the modded game as a starting point to make an entirely new game, often including brand new assets, mechanics, and large teams.

Certainly, there is nothing else quite like The Nameless Mod. While it superficially resembles Deus Ex, The Nameless Mod takes place in Forum City, a virtual representation of the real Planet Deux Forums, an online community of fans. Nearly every character in the game corresponds to a real person who was active in the Planet Deus Ex community at the time, and is overflowing with references, in-jokes, and turn-of-the-century internet humor. The mod today is a barely comprehensible but fantastically endearing slice of internet culture prior to Web 2.0. It’s a game where your character will fight n00bz, sneak by firewalls, journey into old Gamespy message boards, and come across an entire in-game location dedicated to housing Deus Ex fanfiction. Wrapping one’s head around a mod this dense can be difficult 11 years on, so we tracked down two of The Nameless Mod’s creators to help lead us through a retrospective.

“I can’t play it,” says Jonas Wæver, lead designer, project director, and writer on The Nameless Mod, when asked about it 16 years after its development began. “I’ve tried to occasionally load it up again but I just cringe at the shitty writing. I can’t deal. I needed an editor so badly.”

Wæver is only half serious. The game’s 195,000-word script was written primarily by himself, spanning his life from 9th grade to the time he was writing his bachelor’s thesis. Nowadays, he makes games at developer Logic Artists, writing scripts three times the size.

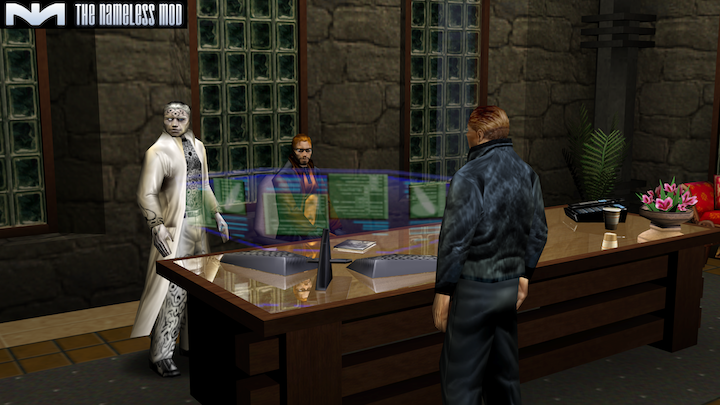

Using a foon weapon in The Nameless Mod

His true feelings are somewhat more complicated.

“I remember it with a lot of nostalgia. It’s fun, it’s unique, it has a lot of personality, but you can’t sell it to people. I think I’m a little sad that it’s such a dumb concept.”

Wæver had an interest in making games from a young age, although his options for getting into games professionally was limited in his native Denmark. After dabbling in Half-Life mods, he managed to land a one-week work experience opportunity at IO interactive, the Danish developer responsible for the Hitman series.

“I managed to get that work experience placement because I sent them a 40-page design document for a different Deus Ex mod that I had been planning, which was something about time police, and a very stupid story,” he recalled.

Jonas Wæver

“They asked me, ‘What do you want to be?’ And I said ‘Well, I kind of want to be a writer, don’t you guys have writers?’ And they’re like, ‘No, not really. We have a contract guy in the basement who occasionally produces text.’ Of course, Deus Ex was evidence that writers are completely a thing. They had three writers on the team. So I realized, okay, maybe there’s a chance.”

Work on Wæver’s time police total conversion mod slowed as he and his team gradually realized they didn’t know how to manage a project of that scope, and he soon joined the Planet Deus Ex forum community as a news editor. That’s when a news tip came through his email about a mod being made by a fellow forum member called Trestkon.

“He had managed to accumulate a team which had some programmers, it had some artists, and it had him as level designer. He didn’t have a story guy and he had no idea what story the mod would have,” said Wæver.

“His idea was he would make a mission set in the Deus Ex universe, but he would use people from the community as the characters. My contribution to that project was, ‘Why don’t we actually set it on the forums and make it a metaphor for the community itself.’ Which was a stupid idea,” Wæver said. “But it worked out.”

Trestkon's dual pistols of injustice

Seven Years of Scope

These days, Lawrence Laxdal is a virtual construction manager for PCL Construction, one of Canada’s largest general contractors for construction. He is passionate about engineering, and although evaluating technology is a major part of his job, he doesn’t immediately come across as a computer geek. But 16 years ago, most people who knew him best, knew him only by his online forum handle: Trestkon.

“I really don’t remember how I discovered that modding could be done,” said Laxdal. “There was a website on IGN’s network called Planet Deus Ex, and they had some very active forums. I’m sure I was probably looking for cheat codes or help on the game, and they had a really active modding section.”

Laxdal admits he had no modding skills of his own at the time but was inspired to make one after seeing other mods and being captured by the idea of making his own game. That’s when the concept of offering to include forum members in the game paid off.

“Everybody wanted to contribute and see themselves in the game, which ended up working out well because we attracted a lot of talent,” Laxdal said. “But also it took seven years to finish.”

Lawrence Laxdal

A couple weeks into the project, Laxdal’s news tip came through Wæver’s inbox, and the two would quickly solidify as the core of the team for the mod’s entire development.

“Without him it would have gotten nowhere,” Laxdal said of Wæver. “He was a huge driving factor in actually getting it done and having a cohesive story.”

While Wæver fell easily into his role as lead writer, Laxdal ended up becoming the primary project manager and jack-of-all-trades, learning to do all sorts of diverse tasks, from video editing, audio editing, marketing, coding, and personnel management.

“We had people with all sorts of different personalities and everybody was working remotely, so you kind of had to interpret what people were feeling and mediate disputes and know when to give and when to pull,” Laxdal explained. “For those seven years we worked more closely together than people do with their real coworkers.”

The aftermath of a shootout in The Nameless Mod

As a mod, everyone was bound solely by their passion for the project, since nobody was getting paid during development and there was no plan to monetize the game when it came time for release. This made “scope-creep” a constant problem throughout development, with various contributors insisting they implement their own personal ideas. Since they were giving their labor for free and the tone of the project was so silly, it could be hard to say no to these increasingly bizarre features. The game ended up stuffed with an almost unmanageable amount of content.

“Nobody on the team were professionals. Everything was chaos,” said Wæver. “I don’t think we got our first dedicated programmer until two years into the project.

“I would say that the most valuable thing I got from all of The Nameless Mod was I learned how to motivate people to do good work without being able to pay them,” Wæver added. “Being able to give feedback in an encouraging way without making people feel like they were getting whipped is a really valuable thing. It’s just about the best game development education that I could have gotten I think.”

Laxdal agrees that The Nameless Mod was a crucial experience for him. “It’s interesting to me how much preparation working on The Nameless Mod provided for this totally different job,” he said. “I didn’t have any special skills. I wasn’t the writer, I wasn’t the coder, but having to tie all those people together, I was always doing a little bit of everything. Knowing at least how something works has been invaluable in my career.”

Fighting off security robots in The Nameless Mod

Giving the Community a Voice

One of the most endearing parts of The Nameless Mod is the characters themselves, and according to the creators, the vibrant personalities found in Forum City were not all exaggerations.

“The community did these weird, almost roleplay-like things on the Planet Deus Ex board,” said Wæver. One of The Nameless Mod’s stranger factions, the Goats, and its rival, the Llamas, were based on real networks of forum users that pretended to be in cults that worshipped animals and mystical cutlery. The playfulness of the community was easy fodder for the developers.

The Nameless Mod’s villain, Scara B. King, was a real forum user who styled himself as an evil billionaire.

“His joke was that he was this super cynical multi-billionaire, and he would roleplay as that on the forums,” said Wæver. Though they accepted nearly everyone who wanted to be in the mod, Wæver worked with them to develop their character and in-game appearance. And once that was all done, it was time to give them a voice.

“That was the real achievement I think,” he recalled.

“At one point we decided that we were going to voice everything,” said Laxdal. “We went out to different websites that have voice actors for hire. Not for money, but who were willing to voice act. It was a nightmare.”

Originally Laxdal was pegged to voice the main character, Trestkon, but soon figured he wasn’t cut out for voice acting. That’s when they decided to spend money on their only paid contributor: a voice actor out of Germany named Jeremiah Costello.

Phasmatis, King Kashue, and Evil Invasion, three forum members represented inside The Nameless Mod

“I had to take the train to Hamburg, then spent the weekend sleeping in his recording studio on the floor,” said Wæver. “He just chewed through those lines, like 10-hour sessions, two days in a row, and then just got all of it done which was amazing.”

The work the team put into gathering voice talent resulted in a fully voiced game that sounds miraculously better than one would expect from what are essentially home recordings from the early 2000s with little quality control. But like everything else in the game, it came together in the end to create a wholly unique result.

The Nameless Mod released to the public on ModDB on March 14, 2009. It was met with positive reviews and industry recognition.

“Of course Warren Spector and Harvey Smith both sent us congratulations,” Wæver recalled.

Warren Spector | Credit: IMDb.

“I frequently wish that I could work on a game like The Nameless Mod again. It was a huge achievement and I’m really proud of it. I just wish that it was easier to explain to other people who don’t already know why it’s so impressive,” he laughed.

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 100,765

https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2020/07/23/warren-spector-on-deus-ex-20-years-on/

Warren Spector on Deus Ex, 20 years on

"I think luck played a big role!"

Deus Ex director Warren Spector has always had very precise ideas about what games should be. A formative D&D campaign run by science fiction author Bruce Sterling. who helped to define the cyberpunk genre, showed Warren the importance of collaborative storytelling early on. “In a book or a movie the writer or director simply tells the audience what they think about a topic. You have nothing to do but decide whether you agree or disagree with the statement being made. There’s nothing wrong with that, but in a game we can do something different – we can set up a situation and let players decide for themselves,” Spector tells me over email.

This is what Warren calls “shared authorship” – something that’ll make immediate sense to those who’ve played tabletop roleplaying games where the general shape of a story might be planned out by a Dungeon Master, but the details are left up to players who often improvise or go off script. “It’s about giving players the freedom to decide how to interact with the challenges the developer confronts them with.”

For example, in any given Deus Ex level, the beginning and end are often meticulously planned out, but the middle sections – how the player arrives at their goal – are given over to them. “We can ask questions like ‘do you kill that person or not?’ and let players decide how to answer through their choices. We can then show them the consequences. That strikes me as fundamentally different. It’s the developer asking a question and the player answering it, followed by the revealing of the consequences which then forces them to make more choices. Shared authorship of the experience.”

One of the joys of Deus Ex is found in breaking it. Overcoming obstacles earlier than intended, or in unexpected ways is part of the appeal of the genre, although Warren says that this wasn’t something they initially designed for.

“It was something that just fell unexpectedly out of the choice/consequence/recovery approach we took. We’d already seen hints of it in the games made at Looking Glass (makers of Underworld, System Shock, Thief) so we had an inkling it was coming. Deus Ex kind of took things to an extreme. We knew it was going to happen and so we tried to proof the game as much as possible,” Warren explains. This involved the team adding things like crates outside of map boundaries, so that when players inevitably jumped over into places they shouldn’t be, they could at least get back on track.

“The reality is that we had an incredible team of designers led by Harvey Smith, who planned for things that, in another project, could have been game-breaking. They bent over backwards to ensure that the game didn’t break when players made choices that were… in a lot of cases, insane. We saw some of them during development and were able to paper over them before we shipped. Players discovered them over the years,” – things like the LAM ladders, where you could place trip mines on walls and use them to scale up bit by bit – “but luckily the game proved more robust than we had any right to expect. I think luck played a big role!”

“There was a lot of content that was easily missed in Deus Ex… I remember having arguments with people at Origin Systems about this years before Deus Ex came out. The prevailing wisdom among developers was that it was expensive and time-consuming to create content, so you wanted players to see everything. I never bought that idea.” Warren and the team at Ion Storm Austin took the opposite approach. Missing content was part of the concept from the start – it was foundational. “It was part of the contract we made with players.”

“I’ve always felt that you want players to have unique experiences – you want them to answer questions differently than other players and see different things as a result.” Warren even has a formula for this. “You want people seeing 70% of your content. But, and this is the critical point, each player should see a subtly different 70%, meaning that the other 30% absolutely belonged to them.” This was why there were such discrepancies when I would discuss Deus Ex with friends twenty years ago, and why sometimes someone would tell you about what had happened in their game and you would simply stare at them incredulously. “No two players would end the game having had the exact same experience, and no playthrough would be the same as the last. I think that’s one of the reasons for the game’s longevity.”

Warren has more than once stated that he isn’t bothered by either the sales or critical reception of his games. Instead, he measures success by the conversations players have around his games. “Some years ago, I gave a talk at The New School in New York and afterwards did something I never do – went out for drinks with folks who’d been in the audience. At the bar, one of them sat down next to me (he was a little drunk) and asked ‘how could you make that right-wing piece of propaganda?’. Before I could answer, another guy walked up and, having overheard, said ‘right-wing propaganda? It was left-wing from start to finish!” The fact is, they were both right I guess, based on how they’d played. I was really tickled by that.”

Warren’s favourite discussions are wrapped up with Deus Ex’s end game. “In a way it was kind of lame – we offered players a Lady or the Tiger situation, (or worse, something like the Match Game!). But as recently as last year I saw a discussion. People were arguing about them, ‘do you really think the world is better off with free will in a new dark age?’ versus ‘how could you go for an outcome where people gave up free will in exchange for peace?’ and so on. The fact that people were arguing about the potential state of the world rather than how to beat a boss made me super happy.”

Deus Ex is continually brought up as an example of a game that seems almost uncannily prescient. Increasingly so. Yes, there’s the fact its New York skyline was missing the Twin Towers, explained as being destroyed in a terrorist attack a year before 9/11 (an accident that had everything to do with the game engine’s technical limits). But it also explored big themes that were rare to see in games – social and economic inequality, revolution and socialism, artificial intelligence and the singularity and so on. I also can’t help but think of how it essentially tells a story about a law enforcement officer moving over to the other side, to the so-called ‘terrorists’.

Warren once said that when it comes to making games, if you don’t have anything to say then you’re wasting everyone’s time. I ask him if he still believes that. “I still believe it’s nice to have something to say – or, more precisely, interesting questions you want to discuss with players. It’s not for me to say what kinds of games people should make, but the fact is we wanted to address big ideas in Deus Ex. We extrapolated from current events back in the late ‘90s, which are sadly still relevant today. I mean, it’s a little freaky that the World Trade Center isn’t in the skyline. The kickoff to the story is the Gray Death, a pandemic that begins with coughing and a fever. The idea that the authorities aren’t always in the right. The risks associated with genetic manipulation, and the dangers of advanced AI. All of those had real-world corollaries back then. We gave everything a conspiratorial spin, of course, but basing your game on real events and fears gives you a better chance of achieving relevance compared with making another game about a space marine who stands between Earth and an alien invasion. I mean, come on – we can do better than that!”

CaffeineConquistador

Learned

- Joined

- May 19, 2018

- Messages

- 415

”...At the bar, one of them sat down next to me (he was a little drunk) and asked ‘how could you make that right-wing piece of propaganda?’. Before I could answer, another guy walked up and, having overheard, said ‘right-wing propaganda? It was left-wing from start to finish!” The fact is, they were both right I guess, based on how they’d played. I was really tickled by that.”

Has the game ever been accused of being antisemitic? The writers weren’t exactly shy about naming old monied family names.