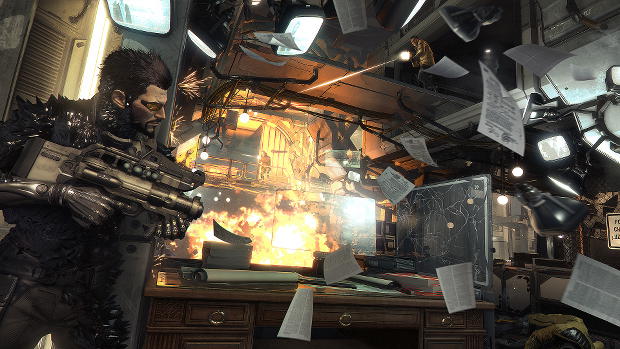

The Design And Politics Of Deus Ex Mankind Divided

At

Gamescom 2015, I had the opportunity to talk to

Deus Ex: Mankind Dividedgameplay director Patrick Fortier. We talked about feeling a sense of ownership over Deus Ex at last, expanding the language of its level design beyond vents, and the politics of a “mechanical apartheid.” Before I

asked him about the game’s ceilings.

RPS: It felt with HR like you were being extremely careful to be respectful to the original Deus Ex, since it was so beloved. I guess this time it feels like you’re making more of a sequel to your own game.

Patrick Fortier: I think so. I think the team feels that that bridge has been crossed in regards the original legacy of Deus Ex and rightly so. I think the fans were nervous originally when the Montreal team started tackling that. Who are they and are they going to be able to do that? But now it has to become its own thing.

It’s been really interesting to

watch some of the original Deus Ex team replaying their own game, and it was so similar, the problems and concerns and trials that they were going through originally. It’s the same thing. I think it’s really important: they had their style, they had their vision, and it was important to stay true to the fundamental pillars of what Deus Ex is, but you also need to have your own vision and flavour as well.

Who knows what happens with the franchise way down the line, but if somebody else ever takes it over they’re going to have to make it their own the way that Montreal made it their own as well. I think that’s really important. So in that sense, yeah, Mankind Divided [

official site] very much gets into that. It’s got the same flavour and style as Montreal has established for the franchise.

RPS: It looks perhaps like you’re expanding the language of Human Revolution, in terms of movement and abilities. How does that impact level design; are you doing things to expand beyond the dichotomy of ‘vent route’ and ‘ceiling beam route’?

Fortier: We are trying to expand it, mostly in the way things are laid out. In Human Revolution you tended to have things that were a little bit piecemeal. You’d have a room with a challenge in there, and that would be closed off with a corridor, and then another room and then another corridor. We’re trying to look at it and create these more circular areas where not only is it this 360 degree base you can infiltrate from the top, the basement, or by making your own hole in the wall, but also architecturally make it a bit more recognisable so it’s easier to project yourself. Who is living there and what are they actually doing there. It’s not just a compound with a series of rooms. That brings its own set of challenges from the gameplay perspective, but there’s been effort put into that.

But are there vents? Yes, there are vents.

RPS: Are the missions more integrated with the hubs, or is it still a case that you get on a VTOL and fly to enclosed locations?

Fortier: There’s still some of that, but there’s a lot of locations like the police station in Detroit [in Human Revolution]. That was its own self-contained little thing within the hub. We really like that approach, so there is a lot of that.

RPS: The Missing Link DLC for Human Revolution had a really great boss fight in it. Is the aim to make the boss fights in Mankind Divided more akin to that, than the rushed originals?

Fortier: That was definitely on the board from day one, when the project was started, that you can go through this game and not kill anybody. ‘Bosses are people too.’ That’s part of what’s been done there.

We also put a lot of work in the combat pillars because we felt we hadn’t quite nailed it in terms of feeling, especially in terms of the audience that comes more from… There aren’t that many games like Deus Ex. There are a lot of other shooters that are much more action-oriented and we wanted the DNA to feel a little more familiar to people who come in with that background.

Which is not to say that we wanted to warp the balance of things; actually, quite the opposite, because if we want to talk about choice and consequence then we have to give you a real choice. It has to be a viable option: that yeah, I have enough bullets and I have enough control that I could decide to tackle this in a combat way. Is that the best choice right now, because I have three guys with titan augmentations and a sentry above and a sniper? Maybe not, but if I have the tools and if you have the talent then you can get through it. So it was just to make sure that if you are going to do that, then it has to be as rich and as developed as the stealth approach, which we felt was really well done in Human Revolution.

RPS: With Human Revolution it felt like there was a pace difference between stealth and combat, or at least the nonlethal and lethal approaches. Stealth encouraged you to move slowly, to crawl, to get close to people in order to use melee takedowns. By comparison, some of the non-lethal tools you’ve shown in Mankind Divided allow for taking down enemies at range and with speed. Is that a deliberate decision to change the pace of the game?

Fortier: I see all the augmentations as tools, and they’re tools with which the player can express themselves, so there are tools to do that but it doesn’t mean… We didn’t warp the whole stealth pillar to say that it has to be faster. It can still be as deliberate and slow and methodical as it was before. You do have tools now though that if you do want to try to change the pace, you can exploit those tools to do that. The Icarus Dash is one example where you can dash straight into cover. You don’t have to use it for offensive capabilities. You can combine it with the cloak and you can be dashing quickly, taking some people out, and obviously there’s a balance there in terms of energy costs as to whether you’re able to do that through the whole map. You’re not going to have a whole lot of these Tesla ammunitions. But yeah, those possibilities are there to get that new breath of fresh air on the stealth capabilities.

RPS: How much research do you do into modern thinking around transhumanism? There’s a lot of complexity to it in the real world.

Fortier: The thing is, we’re two years after the events of Human Revolution, so a lot of that work was originally done by the Human Revolution team. Which isn’t to say that we don’t keep abreast of the developments or that we’re not interested in it, but some of those fundamental questions were explored and studied and documented in Human Revolution.

So, for sure, we’re still always interested, but there was less research on this one than the previous one. The world has been set and it’s much more about dealing with, what’s the new state of this world and how are people reacting to it? There’s the main story beats and you have to figure out what’s going on, but a lot of what I find to be really interesting is that a lot of the side quests explore much more personal stories of individuals. It makes you think. There’s the main thing going on with the conspiracy and the governments and blah blah blah, but in the everyday life of people who have lost a brother or a sister, or who are artists, or whatever walk of life that they come from, the consequences translate differently and you get to explore that and experience that as well.

RPS: With the “mechanical apartheid” stuff, it’s obviously a serious subject. What is the merit of discussing those kinds of issues in what is ultimately an action game? I’m playing devil’s advocate, but in Die Hard, Bruce Willis never strived to be politically relevant…

Fortier: I don’t feel it is an action game. I think we put so much energy into the lore, into the storytelling, into having every pillar contribute to creating this tangible world. The thing about it is, I don’t think we’re using the mechanical apartheid for shock value. We’re not doing it gratuitously. We’re actually dealing with a state of the world that’s logical with the events that transpired in the previous game, and that’s what we’re interested in. How would events like that shape the world and how would it affect people and how do you experience that, and we’re really exploring it with a lot of respect. You are going to go to see what people are living through, even the word ‘apartheid’, if you look at the defintiion, it comes from French for “to put apart”, to separate. It’s a literal description of the situation that our world is describing. It’s not a tagline. It’s not a little thing to get attention. It’s very much at the heart of the storyline that we’re exploring. We don’t feel at all like we’re being careless, we’re not just throwing it around.

RPS: The comparison I just drew was to Die Hard and I guess the difference is that videogames are much more about the world and worldbuilding, so does it therefore–

Fortier: See, again, I don’t really feel that, because we’re doing reviews right now in Montreal and we’re going through some of the streets in Prague, and we’re always making sure that every house has its number, every street has its name. That’s the level of detail that we go to creating this. It’s not just a backdrop. For us it’s a world. Who lives there? How come there’s stuff in this apartment? How come there’s not stuff in this apartment? What’s the story that it’s telling? Why is this piece of machinery here? Who built that? Whose this company?

We’re actually going into that level of detail. We know the background of this company and it’s like, ‘That’s a military company, they wouldn’t make a device like that,’ that’s the kind of conversation we have on the floor all the time. So for me it’s not just, you know, ‘We have a bunch of people, it looks cyberpunk-ish, or whatever’, we put a lot of thought into it.

RPS: That’s sort of what I was getting at. Is the political intrinsic to making a world at that level of detail? You can’t have a world without the political coming into it?

Fortier: Of course, yeah. Yeah. Because that’s the logical setup. That’s what would happen in the real world. There would be influences from the political; there’d be the people in the shadows pulling the strings; there’d be the people on the streets trying to deal with it, being given orders. You’re a cop, suddenly you’re told to go to Golem [a transhuman ghetto in Mankind Divided’s version of Prague], and maybe you don’t agree with the situation but you’re forced into that and you get to talk with every character you meet in the game. You might meet characters who are like that and experience the ambiguity of their situation, so that’s what makes it interesting and what makes it rich.

There’s a depth there. And it’s up to the player to decide how deep they want to go. If they don’t want to pay attention to that and they’re more gameplay-driven, and you want to see the next objective, and you just want to loot for bullets, then I think you’ll have a good time with our game. But if you want to spend a little more time and explore a little more, I think when you turn the game off at night there’s going to be some remnants of ideas and themes that are going to be dancing around in your head.

Especially as the years go by, because we’re dealing with things that are near-future, and some of these things are going to be more and more familiar. We’re going to be faced with these defintions. Where do you draw the line of good augments and bad augments? You get your teeth knocked out, you’re going to get it fixed, and it’s not with a natural thing. Nobody gives it a second thought. But what happens when you start doing something with your eyes that’s not only to bring it back to normal, but it actually enhances things. How are people going to look at you? We’re really close to dealing with these issues?

RPS: Human Revolution had the best ceilings of any game. The art on the ceilings, in multiple rooms, I know people had screenshots of those as their desktop wallpaper. Will the ceilings be as good in Mankind Divided?

Fortier: It depends. In Human Revolution, it was the golden age of the cyber renaissance. The dream was there: augmentations are going to be everywhere, everybody’s going to get them, and they have that palette and those colours. Now that dream is dying. Mankind Divided is much more about corporate feudalism coming back and kind of killing that. So you going to get different kinds of ceilings. The cyber renaissance is still out there, and you can still see glimpses of it, but it’s been pushed into the corners a little bit, so that’s going to affect the ceilings as well. [laughs]

RPS: This is the Star Wars: The Original Trilogy of ceilings, basically. The Millennium Falcon’s all rusty now.

Fortier: [laughing] Right, right.

This interview was originally exclusive to the RPS Supporter Program. Thanks for your funding!

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)