Also yeah, he does regret posting that Episode 3 story

Feature by

Jeremy Peel Contributor

Published on March 1, 2023

“I was deranged,” says

Half-Life writer Marc Laidlaw of his decision to publish the plot of Episode 3 as fanfiction. “I was living on an island, totally cut off from my friends and creative community of the last couple decades, I was completely out of touch and had nobody to talk me out of it. It just seemed like a fun thing to do… until I did it.”

Laidlaw first discovered that community in the mid 90s, in the office of Valve, where Gabe Newell and team were already hard at work on Half-Life. “I’d seen bits and pieces of the levels they were working on, but as soon as I heard the name, I just got this amazing buzz,” Laidlaw says. “I could see the whole world they were aiming at somehow, and I felt it was a collective vision. This is one reason it’s so weird to me when people try to attribute authorship to me that I’ve never felt. It was all there when I got there, in embryo.”

Watch on YouTube

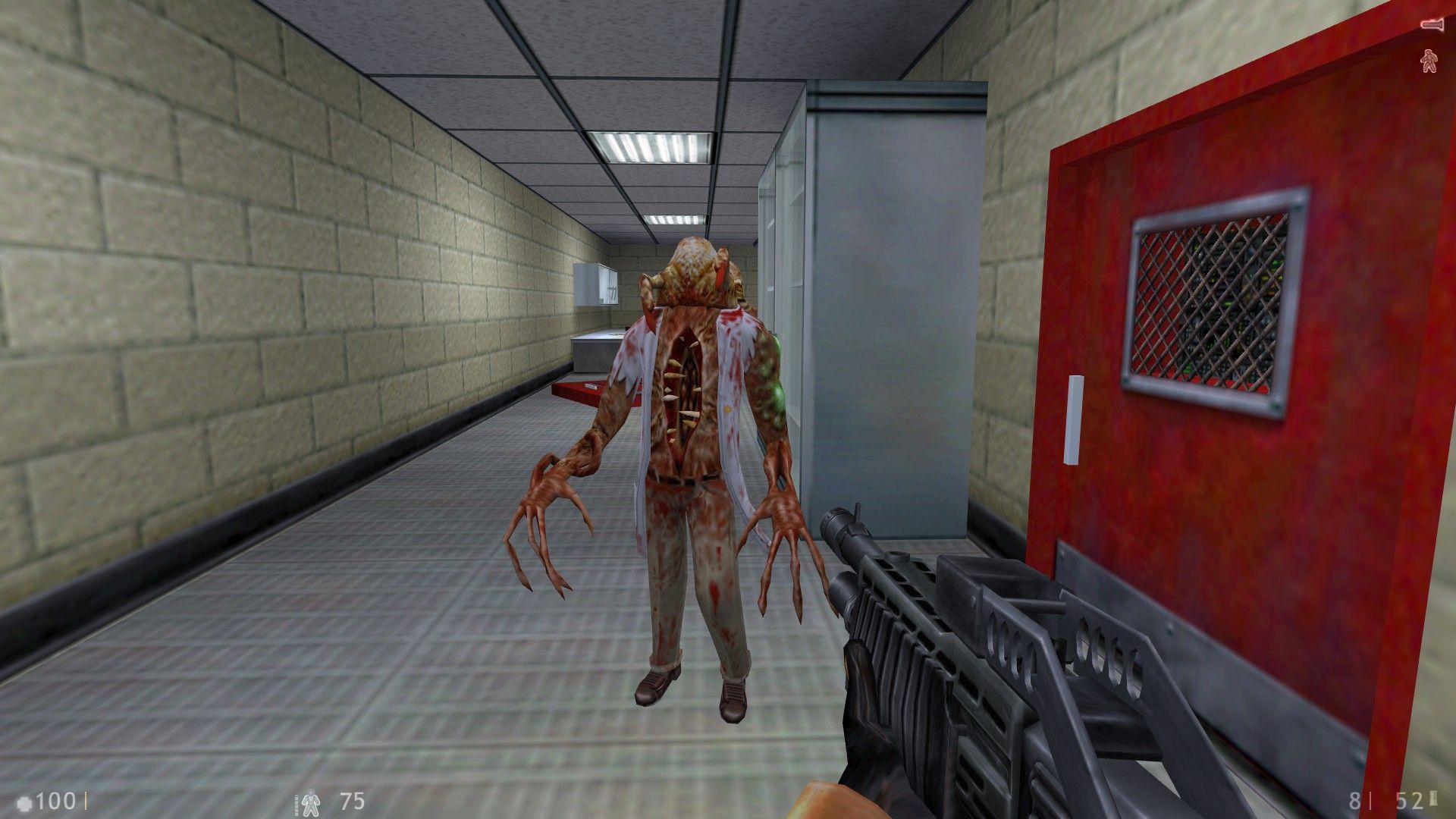

Half-Life was already recognisable as the FPS that would change everything: the disaster at the government lab, the dimensional breach, the battle to break through to Xen and end an alien incursion. Originally, Valve planned to tell its story more traditionally through third-person cutscenes. But when they ran out of time, the team doubled down on the unbroken first-person perspective and found unexpected strengths in it. “The main one was simply the chance to not wake you from the dream,” Laidlaw says. “You were supposed to be alone in this vast scary environment, but also alone in your head, and you could be whoever you wanted to be in that world.”

That loneliness became a defining characteristic of a campaign that only ever granted you temporary friends - an endless succession of AI tagalongs. In fact, by modern standards, there’s very little dialogue in Half-Life. Rather, Laidlaw had the dev team explain the stories they were trying to tell, and helped them solve narrative problems through level design. “Lots of traps and detours and obstacles and occasional moments of breakthrough,” he says. “Really good level design tells its own story. You don’t need NPCs popping up to tell you what to do if your visual grammar is clear enough. Then when characters do pop up, they can say lines of dialogue that make them feel like characters instead of signposts.”

It’s this approach that resulted in Half-Life’s trademark flow and perfect pacing - as well as a lot of black comedy, in which scientists were pulled into vents and belched out again in pieces. Half-Life’s continuous and consistent fiction left you with the sense you were passing through a cross-section of a larger world, rather than a set of fairly narrow levels. Nowhere was this more keenly felt than in its famous opening train ride, into the bowels of Gordon Freeman’s unorthodox and intimidating workplace. That came about when Laidlaw and level designer Brett Johnson decided to fix up some of the latter’s ruined lab areas and bring them to the rest of the team.

“It solved the problem of how to start the game,” Laidlaw says. “The plan up until that point had been to start immediately after the disaster, as the smoke cleared. But after all the work of building broken levels, it seemed like a waste not to get more use out of them. Then we just worked backwards from there to flesh out the preceding events. These were all economical ways of doing storytelling with the architecture - which was my whole obsession. The narrative had to be baked into the corridors.”

Half-Life’s NPCs were primordial. Besides the G-Man, they were all repeating archetypes - scientists and security guards who shared the same voices. For Half-Life 2, Newell tasked Valve’s team with upgrading these characters from automatons to people - developing animated facial features, and mouths that bent into all the right shapes to match their recorded lines. “We had to develop the story in ways that supported all that,” Laidlaw says. “More and better dialogue, richer characters.” As a result, the writer and his colleagues welcomed Gordon into the family of Eli and Alyx Vance. Back then, it was a big swing - action games hadn’t dared tackle anything so domestic, but Laidlaw considers family the “basic dramatic unit”.

“We looked for ways to unify characters and give the experience more coherence,” he says. “As we revised our story outlines, lots of characters suddenly ended up related to each other.”

The wider Black Mesa science team became another kind of family, albeit a far more dysfunctional one. Hal Robins’ generic scientist became the quavering, comic Dr Kleiner, and Black Mesa’s administrator - the same who had pushed for Half-Life 1’s precipitous, disastrous experiment to go ahead - became Dr Breen, the villain who would berate Gordon for misapplying his doctorate in theoretical physics. “If Gordon just popped up in this dystopian future, since he’s a mute conduit with no distinguishing characteristics of his own, how would we even know this was the same guy? By building a community around him, we were able to give him a shape,” Laidlaw says.

Gordon Freeman is canonically a fan of Laidlaw. In his locker at Black Mesa, below his diploma and to the right of a Thermos flask, are two books: The Orchid Eater and The 37th Mandala, the latter of which won the 1996 International Horror Guild Award for Best Novel. Laidlaw blames Valve prankster John Guthrie. “I remember him snickering about it,” he says. “By the time I saw them, nobody was allowed to make any more map changes.”

Laidlaw doesn’t remember any debate about giving Gordon a speaking part as the characters around him evolved. Rather, the hero’s peers started cracking jokes about his silence. “We had the example of Duke Nukem, and wanted to do the opposite,” Laidlaw says. “Our original vision for Gordon was that we didn’t even want to show him on box art. We wanted the player to bring their imagination to this character, and let them talk to themselves as they play, and let that be Gordon’s voice.”

Levity came in many forms, including a singing vortigaunt hidden in a cave off the beaten path, whose chanting ended with a hacking cough. “That was a recording of Gabe when he was in his Tuvan throat singing phase,” Laidlaw says. “He would practice in the elevator and in the parking garage.”

Breen made for a fascinating antagonist - a collaborator slowly feeding his fellow citizens to the alien Combine, who truly believed that appeasement was humanity’s best hope. Speaking down to City 17 from lofty television screens, he was a rationalist rather than a populist - oppressing with appeals to reason, not emotion.

“We knew that we were going to have these monologues running in the background of scenes for aural texture,” Laidlaw says. “When you write something like that, you have to convince yourself that maybe there’s some substance to these arguments.” Breen was influenced by Father Karras, the sociopathic prophet of Thief II: The Metal Age. “He provides an incredible radio show while you’re sneaking around doing thievish things,” Laidlaw says. “I was appalled at myself when I went back years later and listened to those Karras broadcasts, and realised how much I lifted from Thief.”

City 17 itself was defined by Bulgarian art director Viktor Antonov, who guided Valve toward the muted, quietly devastating characteristics of repression in Eastern Europe. “Viktor brought a visionary style that catalyzed a lot of experiments we’d made up until the time of his arrival, so that we could stop floundering, pick an approach, and start honing,” Laidlaw says. “I just tried to match the vibe, to the extent I did, and didn’t really look outside the game for that.”

In the episodic expansions that followed Half-Life 2’s launch, as the Free Man’s legend grew, Laidlaw increasingly played with the fact that the player was always winging it. “Good thing you know what you’re doing,” said Alyx as you disappeared into the heart of City 17’s Citadel to prevent its radioactive core from exploding. Gordon had no masterplan, and to an extent, neither did his writer - who employed the G-Man’s imprisonment of Gordon as a tool to ensure the protagonist could always be mothballed for later.

“I’m not sure I liked it,” Laidlaw says. “I just didn’t know what we could do about it given the way the games had to unfold, as a series of products delivered over time. Half-Life 1 was supposed to be a one-off so the vague resolution at the end was fine for what it was. When we started realizing that this all was going to have to lead somewhere, then we had to wonder where? You’re caught between wondering whether there’s going to ever be another game, and whether this series is going to go on forever. Each of those scenarios demands a different kind of strategy - do you converge or do you open up?”

Laidlaw was initially hired to write for Prospero, the lost early Valve game designed to combine Tomb Raider and his beloved Myst in a sci-fi setting. “It had trouble finding its identity, especially in the industry at that time,” he says. “And before we could go much farther down that road, Half-Life suddenly needed all hands on deck.”

The best Valve could do was cling to a design philosophy of leveraging cutting-edge tech to make engaging games, then making story decisions to support what they’d built. “The story never drives the tech,” Laidlaw says. “I had always hoped that we’d stumble into a more expansive vocabulary or grammar for storytelling within the FPS medium, one that would let you do more than shoot or push buttons, or push crates. Ultimately, I just got tired of the FPS altogether, as a form, and less interested in trying to solve the story problems inherent in a Half-Life style of narrative.”

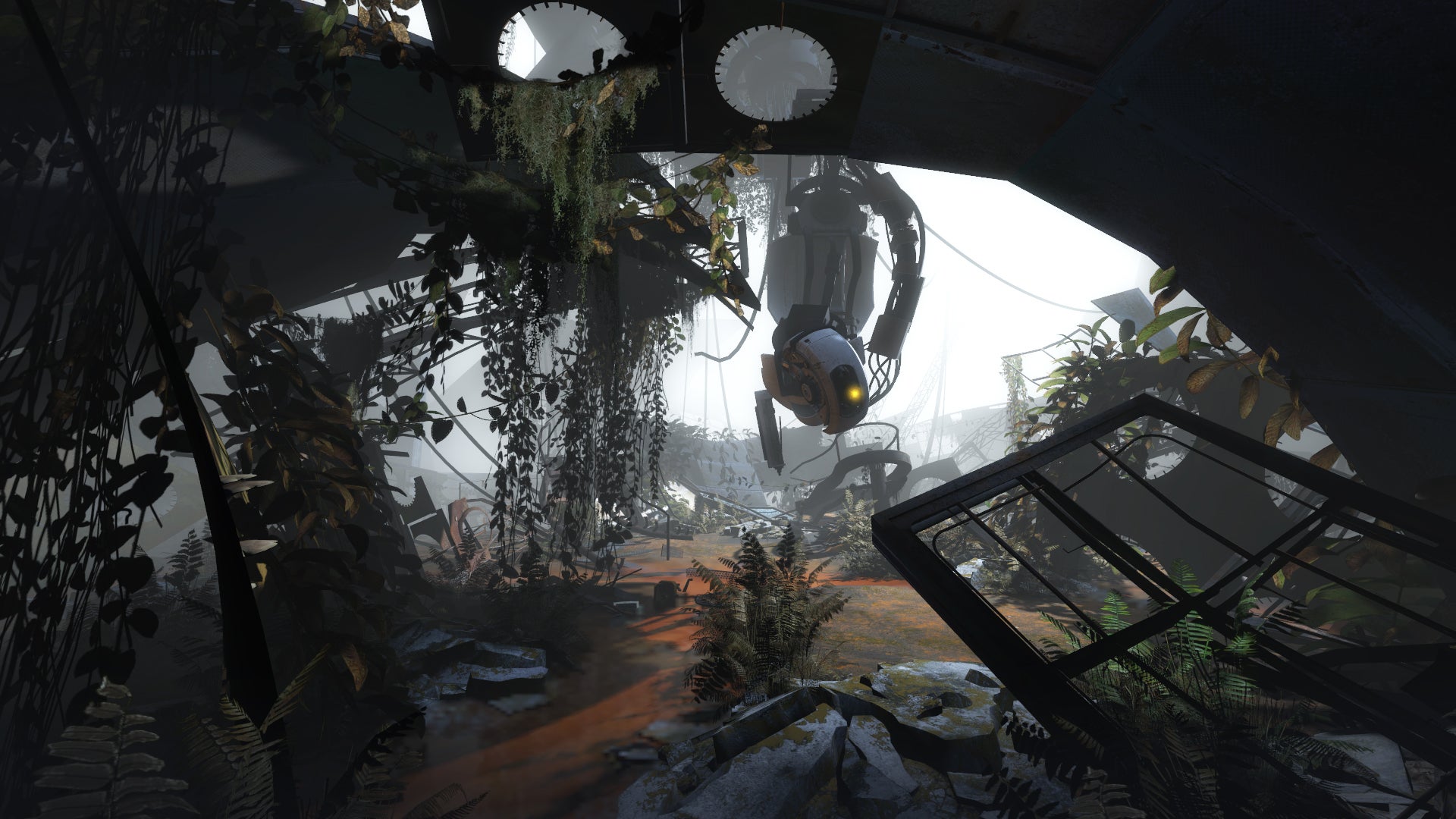

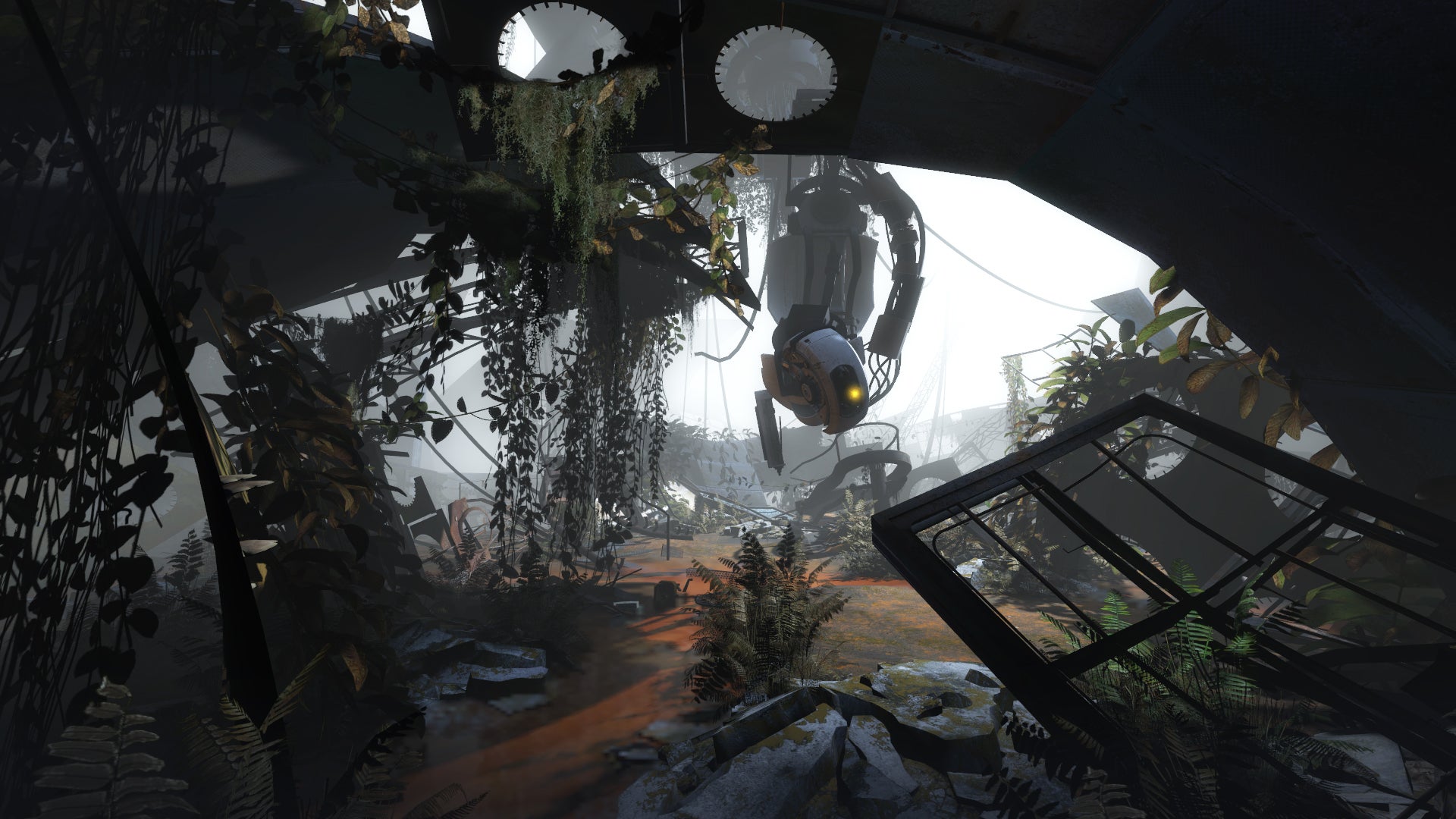

Laidlaw only envisioned a story for the series up until the end of Half-Life 2: Episode 3, which he never got to make. Shortly before leaving Valve in 2016, though, he was leading an early VR project dubbed Borealis, named after the infamous Aperture Science icebreaker teased in Episode 2. “It was too early to be building anything in VR,” he says. “When people are struggling with the basic tools they need to rough out a concept, it’s hard to convey any sort of vision, and it all evaporated pretty quickly.”

The crossover between the worlds of Half-Life and Portal wasn’t Laidlaw’s idea. “I didn’t want it to go there at all,” he says. “I just had to react as gracefully as I could to the fact that it was going there without me. It didn’t make any sense except from a resource-restricted point of view. Portal needed art, and rather than flounder forever looking for something completely new, it ended up drawing on something that looked very Combine-y.”

The connection was well-advanced before Laidlaw realised it would have knock-on consequences for the Half-Life universe. “All we could do is then try to incorporate them somehow,” he says. “I felt like doing this made both universes smaller, but from a franchise branding perspective, that’s a good thing. I eventually did come up with a scenario in which we could connect Aperture and Black Mesa, and we had Borealis lying around from the earliest days of Half-Life 2, so I thought maybe we’d end up with some cool lore and backstory in the long run.”

Laidlaw’s plan for the rest of Half-Life’s story was, during the Borealis project, “very vague and diffuse”. “It’s important to say that every story we did was a thing we discovered along the way, as a team, and not as something I had an idea for and somehow drove people to execute,” he says. “The only way to figure out the story for a Half-Life game was to make the game. There’s no reason to think a thing I put down on paper was going to bear any relation to a final product.”

But of course, Laidlaw did ultimately put Episode 3 down on paper - and publicly. Shortly into his retirement, in August of 2017, the writer posted an epistolary short story on his website, in the voice of one Gertrude Fremont, PhD. “Dearest Playa,” it began. “I hope this letter finds you well. I can hear your complaint already, ‘Gertie Fremont, we have not heard from you in ages!’ Well, if you care to hear excuses, I have plenty, the greatest of them being I’ve been in other dimensions and whatnot, unable to reach you by the usual means.”

Aliases aside, what followed was very clearly recognisable as an outline for an unreleased Half-Life adventure which would wrap up the dangling story threads of Episode 2. The letter was widely interpreted as an admission that players would never get to see this conclusion in interactive form. Today, Laidlaw regrets ever publishing it.

"All the real story development can only happen in the crucible of developing the game."

It would have been best, he thinks, to have kept to himself and dealt with his isolation in ways that didn’t reflect on his former employer. “Eventually my mind would have calmed and I’d have come out the other side a lot less embarrassed,” he says. “I think it caused trouble for my friends, and made their lives harder. It also created the impression that if there had been an Episode 3, it would have been anything like my outline, whereas in fact all the real story development can only happen in the crucible of developing the game. So what people got wasn’t Episode 3 at all.” Instead, it was just a snapshot of where Laidlaw was at that time. “Deranged,” he repeats. “There’s really no other explanation.”

Laidlaw has otherwise kept his distance from Gordon, or Gertie. He didn’t consult on Half-Life: Alyx, despite reports to the contrary, but gave its writers his blessing. “I wouldn’t have wanted anyone second-guessing me, and I had total confidence in Jay Pinkerton and Erik Wolpaw to do good inventive work,” he says. “I intended to play it at some point but… I never got a PC, so I’m starting to think I probably never will play it. I don’t ever need to see another Combine soldier again, not even in VR.” The last place on Earth he’d ever want to go back to is City 17. “They nuked Black Mesa because of me,” he says. “Just so I wouldn’t have to see it again!”

Laidlaw had a fantasy that, having retired from games, he’d return to his original calling and publish novels again. In 2018, living through a post-flood lockdown on Kauai, he wrote Underneath The Oversea - the culmination of the lessons he’d learned in writing dialogue and plotting adventures at Valve. “I was pretty happy with it, and blithely sent it out for my agent to shop around,” he says. “And it was roundly rejected everywhere it went.” Ultimately, Laidlaw self-published on Kindle, to “zero notice”.

“What I hadn’t realised is that if you stop writing books for 20 years, everyone forgets who you are,” he says. “If you’re, say, around 60 years old, you’re going to be dead soon, so there’s not much reason for publishers to start trying to build an audience.” Today, he mostly makes music instead: “I can’t seem to stop chasing ever smaller audiences.”

Yet Laidlaw’s stories have entertained millions - even if, like Gordon, he’s very often chosen to take his voice out of it and let the corridors do the talking. “From my first visit to Valve, I had many conversations with people who shared my vision of integrating narrative and level design - specifically, how you would make that architecture do your storytelling,” he says. “I only wanted to think about the FPS experience. It just seemed the most involving and interesting for narrative, because it put you right into the middle of a story the way a novel did.”

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)