Brian Fargo: The Maverick Who Made a Wasteland of the RPG

By

Julian Benson on 13 Jun 2015 at 2:00PM

You may only know him from his Kickstarter videos but Brian Fargo is one of the most influential figures in the games industry. The impact of his work can be felt in almost every game in every genre that’s been released in the last decade. And, today, he’s still revolutionising how the industry works.

As a teenager, Fargo was a socialite, splitting his time between his friends in the chess club, his D&D roleplaying group, and competing as an Olympic-hopeful sprinter. He could have gone onto university on a scholarship but that changed when his parents bought him an Apple II computer. Fargo fell into game development, spending his evenings and weekends programming games with his friend Michael Cranford.

In the summer of 1982, after finishing high school, Fargo started making games under the label of Saber Software. He roped in Cranford from his D&D group to draw the artwork and convinced another friend to help him out with some of the engine code, and together they made an adventure game called

The Demon’s Forge.

Fargo licensed this cover art despite there being no scene like it in The Demon’s Forge, something that would cause him to receive confused phone calls for years to come.

Fargo licensed this cover art despite there being no scene like it in The Demon’s Forge, something that would cause him to receive confused phone calls for years to come.

When it came to promoting the game, Fargo showed off a stroke of devious genius. He had only $5,000 to develop and market the game, so he spent half of that to buy a single ad in a magazine called Softalk, one of the only nationwide computer magazines around at the time. He’d then call up retailers from his home phone and say he was trying to find a copy of

Demon’s Forge, a game he’d seen in that month’s copy of Softalk. The retailer would say they’d look into it and then minutes later he’d get a call back his Saber Software line from the retailer who, not realising it was Fargo who had called before, would place an order.

This canniness for self-promotion is something that would stand Fargo in good stead throughout his career.

Fargo was running the entire business himself, making copies of the disks, packaging them, and selling them on to retailers from his home. His success attracted the attention of Michael Boone, an old high school friend who had come into some money.

Boone fancied himself an entrepreneur, too, and wanted to start a software company, so he bought out Saber Software and brought Fargo in on the business. It was here Fargo got his first (dis)taste of corporate ownership.

“They made me the vice president and I started doing work for them,” Fargo said in a Gamasutra interview in 2013. “It became one of those things where there were too many chiefs and not enough Indians, and I was doing all the work.”

Boone was a volatile company to work for and one without a clear vision. The group had hired a set of developers–Fargo, “Burger” Bill Heineman (now Rebecca Heineman), Troy Worrell, and Jay Patel–but didn’t know what to do with them. One day Boone decided he didn’t want to be in the software business, he wanted to be in the whiteboard business, and fired them all on the spot.

Luckily, Fargo had been setting up a deal on the side. An old teacher from high school was looking for a programmer to do some contract work for the World Book Encyclopedia. Fargo took the $60,000 contract and, with the other fired developers from Boone, started a new studio: Interplay Productions.

After a few months of scrabbling for any development contract he could find, Fargo managed to get on Activision’s radar, and signed on to a three game contract. The team made two adventure games (

Mind Shadow and

Tracer Sanction), but, for their third game, Fargo wanted to move away from adventure games. He wanted to take on the biggest game on the market:

Wizardry.

“At the time

Wizardry was the big thing, it was the top seller,” Fargo told Matt Barton back in 2011. “In magazines you’d see the top selling software and you’d see Bizi Calc, which was like Excel, and you’d see a word processor, and then you’d see

Wizardry. It was the de facto standard.”

Wizardry

Wizardry had tapped into the popularity of D&D and reworked its rules into a dungeon crawler. You would guide a party into black & white tunnels filled with monsters, fighting your way deeper and deeper into a set of virtual mines. The game had been a massive success on the Apple II but its developers had been slow to port it to other platforms and hadn’t updated its technology since release.

Fargo knew he could make a better game, one with colour, sounds, music, and better art. He got in contact with his old friend Michael Cranford, who had done the art for

The Demon’s Forge, and contracted him to write the story and design the dungeons. But Activision didn’t want it. Then CEO Jim Levy

reportedly called Fargo’s idea“nicheware for nerds”. So Fargo took it to Activision’s competition, Electronic Arts.

EA signed Interplay immediately, inking a deal for Fargo’s team to make

Tales of the Unknown: Volume I - The Bard’s Tale. Interplay became one of the only studios to work for both Activision and EA at the same time. Half of the team was working on ports of the Activision adventure games while Fargo, Cranford, and Heineman worked on

The Bard’s Tale.

“One of the big things at the time was, they hated each other, Activision and EA,” Fargo told Gamasutra. “Just hated each other. We were maybe the only developer doing work for both companies at the same time and they would just grill me whenever they had the chance. Whenever there was any kind of leak, they'd say, "Did you say anything?" I was right in the middle, there. I always made sure to keep my mouth shut about everything.”

Work on

Bard’s Tale was going well until, a month from release, Cranford grew frustrated with his deal. He wanted royalties from the

Bard’s Tale sales, something no one on the team had because Fargo was insistent profits should be poured back into the games they were making.

Cranford took the master copy of the finished game hostage. Fargo was going from meetings with EA, telling them their game was complete, to negotiations with Cranford, trying not to let on to the publisher what was going on. Eventually Cranford got his royalties but, after his work on the

Bard’s Tale sequel, he’d never work with Fargo again.

Bard’s Tale was a phenomenal success, selling more than 300,000 copies. Not only did it shoot past

Wizardry in the charts, it eventually came to make close to 10 per cent of all of EA’s profits in 1985.

Over the next two years Interplay made three

Bard’s Tale games for EA, each larger and more complex than the last. But

Bard’s Tale was nothing on Fargo’s next idea.

Fargo had been a fan of George Miller’s

Mad Max films since he was a teenager. He wanted to create a game that captured that wasted Earth. He wanted to make an RPG but one with a richer story than

Bard’s Tale, one with more choices (and consequences). So, along with Ken St Andre, Michael Stackpole, and Liz Danforth they started designing one of the first open world games:

Wasteland.

Whereas each

Bard’s Tale was completed in a year,

Wasteland took Fargo’s team five years to finish. It was a sprawling epic of a game where players decisions rippled out through the game world, sometimes not causing repercussions in the story until hours later.

Critics and fans loved it, even now,

Wasteland is still included on ‘Best of’ lists. though it would be 25 years till Fargo got to make a sequel.

Fargo had worked out by 1988 that the real money in the games industry came from publishing, EA and Activision had mopped up on the success of his games so he wanted to move Interplay into the publishing business (a move EA didn’t take kindly to).

When Interplay announced it was going to self-publish

Battle Chess, a game inspired by the animated chess set in

Star Wars, EA cancelled

Bard’s Tale IV. The team was three months away from release. Fargo renamed the in-production

RPG Dragon Warsand had the team go through the code and remove any reference to

Bard’s Tale and, because it didn’t have any before, throw in some dragons. (As with

The Demon’s Forge, Fargo would get calls for years about the mismatch of the cover art and the game’s content.)

EA would hold onto the

Bard’s Tale name for the next 27 years, preventing Fargo from making a full-blooded sequel.

Along with

Battle Chess, Interplay started publishing games and fostering new talent. One of the first games it published was from a studio called Silicon and Synapse, first a game for the SNES called

RPM Racing, then

Lost Vikings. Fargo offered to buy the studio, but the team who had grown larger with its partnership with Interplay, remained separate and renamed themselves Blizzard.

Fargo published a mech game from another startup. Shattered Steel wasn’t a success but Fargo kept working with the group, he saw something in the studio, sure that Bioware would amount to something.

With EA still in control of the

Wasteland license, Fargo was forced to come up with a new series when he wanted to return to the post-nuclear war setting. He licensed an RPG ruleset called GURPS and set his team to work on a game called

Fallout. He wanted to capture the moral bleakness, black humour, and violence of apocalyptic stores of Mad Max and Swan Song by Robert McCammon.

With the game deep in production, Fargo showed

Fallout’s intro video to GURPS’ creator Steve Jackson:

Jackson was repulsed by

Fallout’s violence and refused to let the team use his ruleset unless Interplay toned it down. But Fargo refused. “I had certain sensibilities of what

Fallout should be,” Fargo said in the Barton interview, “so we dropped out of the Steve Jackson deal and created our own system.”

The team had to build a whole new ruleset to line the core of

Fallout. The hard work paid off;

Fallout was a huge success for Interplay. And, its trailer, which so repulsed Jackson, has gone down in history as one of the best game videos ever made. When Bethesda revealed

Fallout 4 last week it begins with an homage to those famous opening shots.

The team went on to make

Fallout 2, Planescape Torment, and the

Icewind Dalegames. Fargo published Bioware’s first big hit,

Baldur’s Gate. Interplay led the industry in the 90s, producing a string of RPGs which are today still considered the best in the genre.

At the same time Fargo published the first game from a small team called Treyarch, the studio that went on to to make

Call of Duty: Black Ops for Activision, one of best selling games

of all time. He also discovered and published Parallax’s Descent and Volition’s

Freespace games–seminal space shooters which are still being improved with mods today.

Despite these classic games, Interplay was losing money. It was publishing lots of games that just weren’t selling enough to make big profits for the team. Eventually Fargo took the company public and a French group called Titus bought up a stake in the business. Fargo didn’t get on with his new owners and, in 2002, resigned.

Without him Interplay never released another classic and shrank from more than 500 employees to today’s meagre ten.

Fargo formed the appropriately named InXile Entertainment in 2003 and bought back the rights to

Wasteland from EA. For nine years he tried to get a publisher to give him the money to make a sequel to his classic RPG but, even though Bethesda’s

Fallout 3had been a huge success, Fargo couldn’t get funding to make his return to the post-apocalyptic setting.

Then, Double Fine made history by funding an old-school adventure game through Kickstarter.

Fargo saw his chance and took it. In April 2012 he launched a campaign to raise $900,000 to make

Wasteland 2:

When the campaign closed a month later he had raised nearly $3 million.

Wasteland 2still stands as one of the highest funded projects on Kickstarter. Following his success a string of industry veterans raised money through the crowdfunding platform, emulating Fargo and Double Fine’s success.

A year later Fargo returned to Kickstarter, this time to fund a successor to another Interplay classic,

Planescape Torment.

Torment: Tides of Numenera raised more than $4.1 million.

Fargo embraced this interaction with a community and released the first public build for

Wasteland 2 through Steam Early Access, the largest developer to do so. It was met with huge success raising funds that, like in his days on

Bard’s Tale, were taken and poured straight back into development.

When

Wasteland 2 was released in 2014 it was an immediate hit, securing InXile’s future.

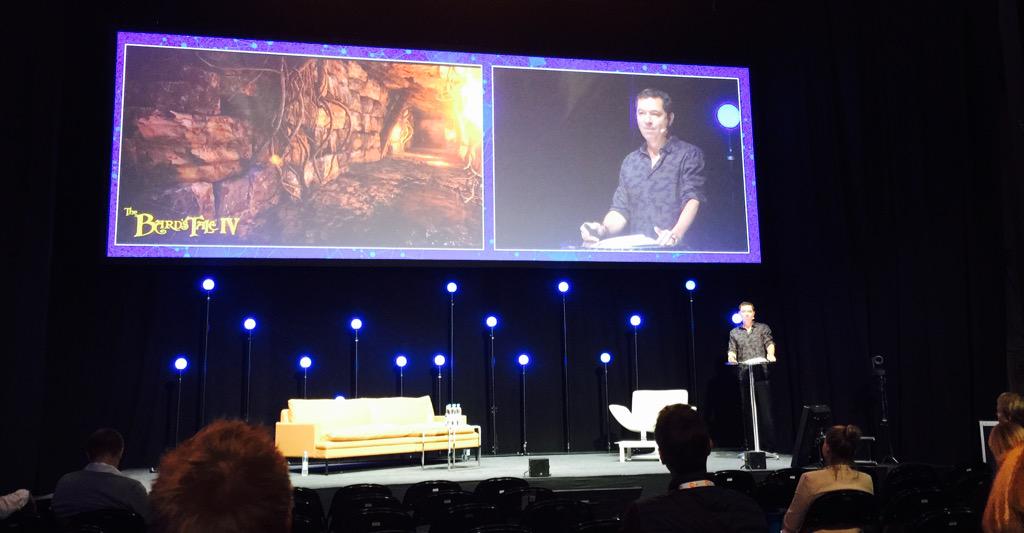

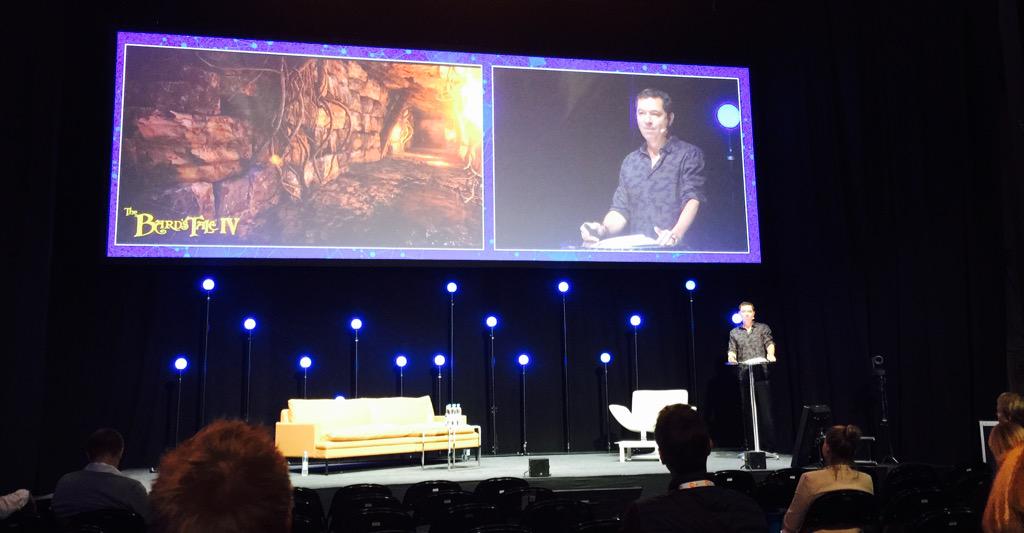

Now, 30 years after the original, Fargo’s finally making the fourth

Bard’s Tale game. Again he’s raising funds through Kickstarter, this time aiming for a $1.25 million target but he’s committing $1.25 million of InXile’s own money, earned from

Wasteland 2sales, to make a fully updated version of the dungeon crawler series in the Unreal 4 Engine.

It’s difficult to gauge the full impact of Fargo’s influence on the industry but he found pivotal work for the developers who formed Blizzard, Obsidian Entertainment, Bioware, Treyarch, and Volition. Studios that have shaped the industry with games RTSs like

StarCraft; MMOs like

World of Warcraft and

Star Wars: The Old Republic; RPGs like

Baldur’s Gate, Mass Effect, and

Fallout; and shooters like

Call of Duty: Black Ops. He’s also had a direct hand in the development of some of the industries greatest RPGs.

Simply put, without the boldness of Brian Fargo the games industry wouldn’t look like it does today.

![Glory to Codexia! [2012] Codex 2012](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_slushfund2012.png)