Kickstarter’s next campaign

The original crowdfunder is loosening its rules and opening the floodgates

When NBC Nightly News aired a segment last week about the revival of the public television show

Reading Rainbow, the anchor didn’t pause to explain where the money came from. “Longtime host LeVar Burton launched a Kickstarter campaign to bring it back,” correspondent Janet Shamlian gushed, as the camera showed numbers ticking up on the project’s funding page. “His goal was $1 million in 35 days. He had it in 11 hours.”

In the past, Shamlian would have explained that Kickstarter was a crowdfunding website, or perhaps “a new kind of social network helping artists fund their projects,” as the network

explained it in 2011. No longer. People know what Kickstarter is now – the term is

eight times more popular on the internet than the generic “crowdfunding” – and they know how it works. They understand that projects don’t get funded until they hit their goals, they realize they won’t get their money back

if the project fails, and they get that Kickstarter is

not supposed to be a store.

Kickstarter has raised $981 million on its way to becoming a household name. Yet that money comes from a small number of projects: just 62,932 campaigns have been funded. If everyone has the potential to be a creator, as the crowdfunding movement would have us believe, there are many, many more people to reach.

That’s partly why the company is

announcing two major changes today aimed at presenting a "simpler, friendlier Kickstarter," in the words of co-founder and CEO Yancey Strickler. First, the rules for creators have been simplified from about 1,000 words to

less than 300, and previously banned products are allowed back on the platform. Second, projects can now opt to "Launch Now" and bypass Kickstarter’s approval process.

At first, the changes may seem like a capitulation to market forces over principles. In January, Indiegogo raised $40 million from its own investors,

the largest financing round for any crowdfunding startup, in part because its liberal acceptance policy has allowed it to grow fast. Campaigns on Indiegogo aren’t vetted, and its rules are ultra-simple: anything that isn’t illegal or dangerous, goes. "Indiegogo has no opinions," founder Slava Rubin told

The Fiscal Times. "It has no judgment." Indiegogo has hosted more than 200,000 campaigns in more than 200 countries compared to Kickstarter’s 149,541 in five countries.

By contrast, Kickstarter has always seemed a bit restrictive. "Everything on Kickstarter must be a project," the old rules began. "Every project on Kickstarter must fit into one of our categories." The rules prohibited ultraspecific things like sunglasses, bath and beauty products, hardware projects that offered rewards of more than one item, and software projects not run by developers. Charities and "fund my life"-style campaigns were blocked. Instead, Kickstarter emphasized its goal of funding creative ventures with a shareable result. When Kickstarter

rejected writer Brenda Winter Hansen for trying to raise money for workshop tuition, she went with Indiegogo.

Under the new rules, Hansen’s campaign might pass. In general, Kickstarter will now only prohibit things that are illegal, regulated, or dangerous, Strickler says. Pretty much anything else will fly, he says, as long as creators are honest about what they’re doing. Charity,

genetically modified organisms, and misleading photo-realistic renderings are still forbidden under the new rules, but sunglasses, bath and beauty products, and many items that were banned over time are back on.

Strickler has never been happy about the fact that a creator’s Kickstarter experience starts with an approval process. "You always hate saying no to someone," he says. "[But] for a brand or a community to have definition, there have to be rules. Every website in the world has a list of what’s on topic and what’s off-topic. But you want those to be as broadly defined and clearly understandable as possible, and I don’t think that’s always been the case."

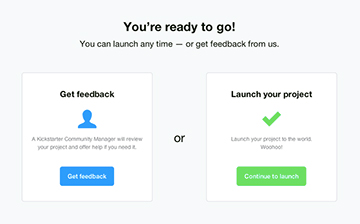

Kickstarter’s human approval process was never billed as an endorsement — it consisted of a simple check for rule violations that could take as little as five minutes. That check will now be done by an algorithm that looks at keywords in the campaign, the creator’s track record on Kickstarter, and other metrics to create a profile of the project and compare it to similar projects that have been approved, rejected, flagged, and removed. If the campaign passes the algorithmic check, the creator can choose to either launch without a human review or request feedback from the Kickstarter team.

This will speed up the approval process for new campaigns and give staffers time to work in more depth with creators, Strickler says. Kickstarter was already approving 78 percent of new campaigns, and 44 percent of those get fully funded, according to the company.

If the history of the company were divided into eras, Strickler would say there are roughly four. The first would be 2002 to 2009, Before Kickstarter, when Strickler and his co-founders Perry Chen and Charles Adler were dreaming up the site. The second would be 2009 to March of 2012, Before Double Fine — the first "blockbuster" project that collected

more than $3 million for a video game and raised expectations for funding levels. The next would be After Double Fine, which saw the famous "

Kickstarter is not a store" blog post and a number of multimillion-dollar projects.

This would be a new one, Strickler says. We’ll call it the Mature Era. The site is "the premier place" for crowdfunded projects, Strickler says, and the company boasts a brand recognition and community of repeat backers not found on other sites. Even though Indiegogo has surpassed it in size, Kickstarter’s campaigns are much

more likely to meet their goals and have raised more money total.

The question is whether Kickstarter can loosen up its rules without compromising its cachet and attracting

scams,

crazies, and

purveyors of schlock. "The world has changed in response to Kickstarter and we’re changing with it," Strickler says. Hopefully that doesn’t mean being overrun by knock-off Ray-Bans.

![Have Many Potato [2013] Codex 2013](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_potato2013.png)

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)