The jaws of Oblivion: Saving the Elder Scrolls MMO

The long road to The Elder Scrolls Online’s latest update, One Tamriel

How do you take one of the biggest franchises in games and move it to an entirely different genre without losing what makes it special?

That was the question posed by the team at ZeniMax Media when it formed ZeniMax Online Studios in 2007. Its answer was

The Elder Scrolls Online, an ambitious project to take the world of Tamriel — made famous by single-player games like

The Elder Scrolls: Morrowind and

The Elder Scrolls: Oblivion — and reshape it into a massively-multiplayer online game.

But in 2011, four years after work began, studio director Matt Firor and his team started to think they might be on the wrong track. The feedback from internal playtests was mixed.

ESO was just OK, and OK wasn’t anywhere close to good enough.

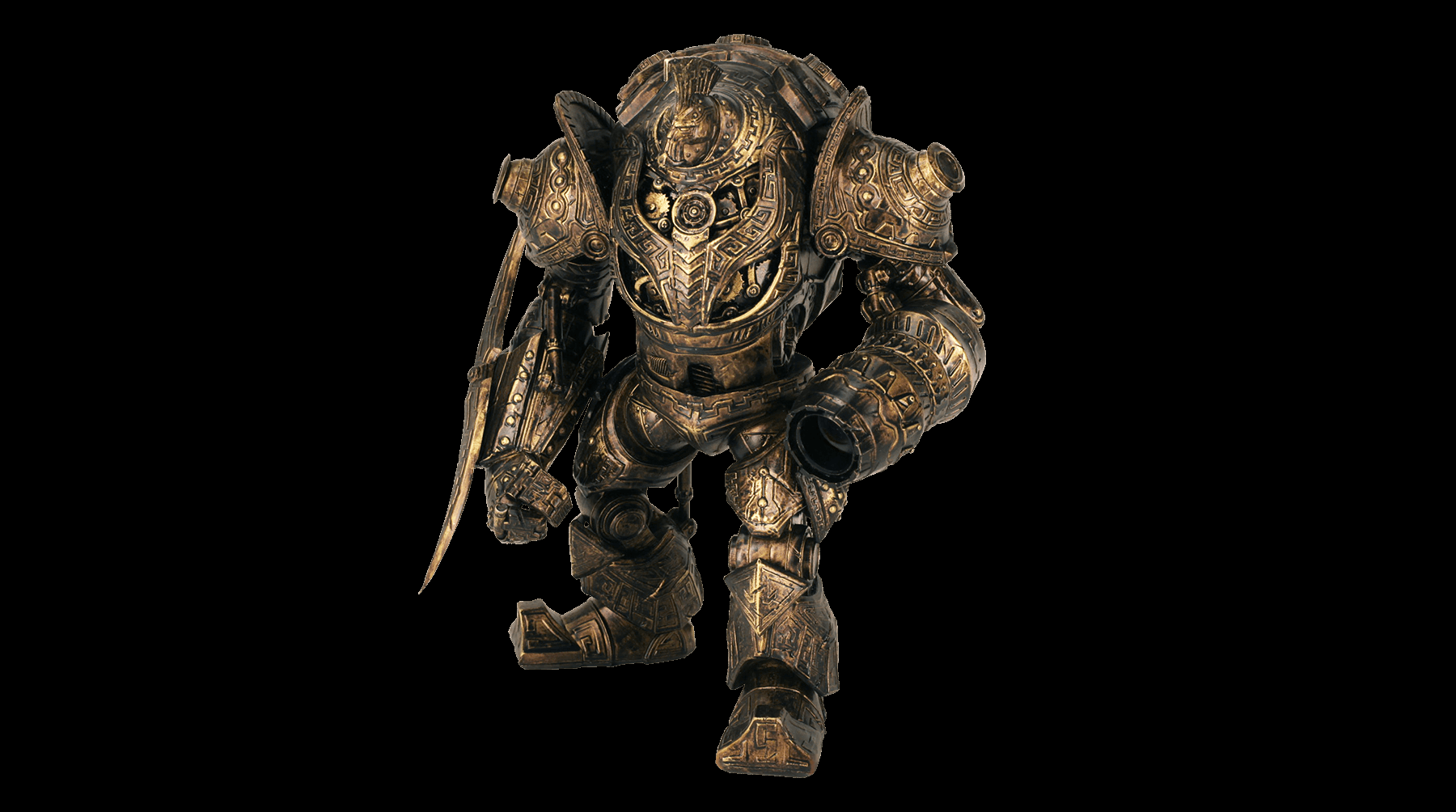

The Elder Scrolls Online: Tamriel Unlimited circa 2016.

A CHILL WIND

"Basically," Firor told Polygon last month, "the feedback was [already telling us] it’s not the next Elder Scrolls game.’"

And, at least chronologically speaking, it wasn’t.

The Elder Scrolls: Skyrim launched in November of 2011. It was the product of ZeniMax Online’s older sibling, Bethesda Game Studios. The game was a critical darling, giving the Elder Scrolls formula a kind of clarity and fidelity that enabled the franchise to add millions of new fans. It was a smash hit at retail and online and, to this day, it remains one of the most actively played games on PC.

But for Firor’s team,

Skyrim’s success led to an unexpected crisis. The potential audience for an Elder Scrolls MMO was bigger than ever before, piling on fans who were intimately familiar with what made the series so special — an expansive open world that players could lose themselves in.

Skyrim had changed player expectations completely. The bar hadn’t simply been raised for ZeniMax’s MMO. It had been welded into place in an entirely different location.

SKYRIM HAD CHANGED PLAYER EXPECTATIONS COMPLETELY.

So Firor and his team did the only thing they could: They set about rebuilding their vision for the game. It was a transformation so vast that when

ESO launched on Windows PC in April of 2014, the list of changes was barely halfway done.

Their work wasn’t over when the game changed its name to

The Elder Scrolls Online: Tamriel Unlimited, or when it launched on modern consoles just a few months later in June. They weren’t finished when the game abandoned its subscription model

in favor of something different, or when it launched five major pieces of downloadable content in quick succession.

And the transformation of

ESO won’t be truly complete until next Tuesday, on Oct. 18. That’s when the next free content update, called

One Tamriel, launches on PlayStation 4 and Xbox One.

Only then will

ESO finally achieve the goals Firor’s team set in early 2012.

To tell that tale, ZeniMax Online recently invited Polygon to its headquarters in Hunt Valley, Maryland. The story begins, like any good epic, in the middle of things.

CIVIL WAR

"Son, you’re in the wrong faction!"

Late last year, Pete Hines, vice president of public relations and marketing for ZeniMax Media’s publishing arm Bethesda Softworks was screaming at his youngest son in the next room.

He had had one job, and he’d screwed it up.

"I’ve played

Elder Scrolls Online on PC and I’ve played it at home on the Xbox One," Hines told Polygon. "One day, my youngest son asked, ‘Hey dad, can I try

ESO?’ I said, ‘Yeah sure. Here ya go!’ And I loaned him my copy and set him up with an account."

ESO is unique among MMOs in that it’s built with a single, unified server infrastructure. The entire game is hosted on what ZeniMax calls its megaservers, a proprietary system that lumps all the players more or less together in the same virtual world.

With MMOs that had come before, games like

World of Warcraft and Matt Firor’s previous project,

Dark Age of Camelot, player communities were separated into various shards. Each shard was a mirror image of an identical game world, and players on different shards could never interact with each other.

But players in

ESO have always played in the same world and on the same megaservers, hundreds of thousands of them at one time. And yet, a year and a half after it had launched, there was still something keeping them apart.

In the fiction of

ESO, the Aldmeri Dominion, the Daggerfall Covenant and the Ebonheart Pact are locked in a three-way battle for control of the continent of Tamriel. Set in a timeline hundreds of years before the events of

Morrowind,

Oblivion and

Skyrim, this war is the central narrative element that drives

ESO.

Some of the first promotional images ever shared for The Elder Scrolls Online highlighted a three-way battle for control of Tamriel.

It’s also what kept Hines and his son from playing together.

"I told my son, ‘By the way: This is the faction that I’m in, this is my character and you should join my faction so we can play together.’

"At the time, he was 11 or 12, and of course he doesn’t listen or he didn’t remember. When he got around to playing, he joined a different faction. He and his friends had been playing and playing and playing, and one weekend he said, ‘Hey dad, we should play

ESO together!’ I said, ‘Let’s go!’ And we went, and we both loaded up the game and we went to go play and I’m yelling, ‘Tyler! You’re in the wrong faction!’"

Hines said that he could have made another character to play with his son, but he had already grown attached to his character.

"It seems like such a small thing," Hines said. "But you make these choices in the game, and you start investing all this time in a character. One of us could have started over again, but that totally defeats the purpose.

"It’s just funny that little things like that are so frustrating. Why can’t I just do this?"

"THEY’VE SPENT A LOT OF TIME DOING ADDITION BY SUBTRACTION."

The same factions that kept the Bethesda vice president from playing with his son are a holdover from the original design of

ESO from 2011, and maybe even earlier. While technically feasible given the megaservers on which everyone plays, the restriction was baked into the rules of the MMO at a foundational level.

It’s just one of the things that director Matt Firor and the team at ZeniMax Online have been trying to change since 2012.

"They’ve spent a lot of time doing addition by subtraction," Hines said. "Can you play with somebody who’s a vastly different level than you? Can you play with somebody who’s in a different faction? Can you go to other areas that are faction-specific if I’m not in that faction? And over the development they’ve made strides, and ever since launch day

One Tamrielhas been, in a lot of ways ... the last barrier that remains."

But there were many, many steps along the road to

One Tamriel.

PEAK MMO

Back in late 2011, Firor and his team had a working alpha up and running at the ZeniMax offices.

Firor recalls the initial round of in-house playtesting. That’s when the first alarm bells started going off. People, like Pete Hines who had been with the company around 12 years at that point, weren’t seeing the kind of things that they wanted to.

"People were saying, ‘This is a competent 2004-era MMO,’" Firor said. "We needed to make it much more than it was. If I was a

Skyrim player, and I'm going to transition to this, it could feel a

little different. I could see other people around me in the game world and everything. But it had to feel more like

Skyrim when you sat down and played. And it didn’t.

"So we made a list," Firor said, pointing to a whiteboard in the conference room where we sat with a PR representative. "A big list."

They had just 18 months to go before beta testing.

And early version of The Elder Scrolls online from 2011.

One of the first things to go was the user interface. Multiple lines of user-configurable commands were dropped in favor of a lean, flexible set of skills on a single toolbar.

Next, they had to change the game’s targeting system. In a classic MMO, you can’t just swing your sword around at random or cast a fireball into the air. ZeniMax had to revamp its targeting systems to allow players to express themselves, just like in every other Elder Scrolls title. It had to feel like the single-player games.

Up until that point, most fans had only ever experienced an Elder Scrolls game in first-person. But the game that Firor’s team had built was third-person. So an ongoing project was to bake in an entirely different perspective. It involved reworking the game’s camera, player animations and even the game’s architecture. When it was first shared with the press in 2013 reactions were tepid, including those

here at Polygon. The system would continue to be refined over the next year.

An early version of The Elder Scrolls Online from 2011.

Perhaps the most tedious job was adding more interactive physical objects into the game world. One of the quirks of Elder Scrolls games is that nothing is bolted down. Some

Morrowind and

Skyrim players have developed a kind of in-game kleptomania, collecting random objects until they have

hundreds of pillows or entire 18-person place settings squirreled away in a chest somewhere. To meet that expectation,

ESO needed loot, and lots of it.

Every barrel, every box and every shelf fit for the purpose had to have something on it that players could make off with. A gang of nine interns was conscripted to spend weeks adding thousands of interactive objects into the game. The project came to be known internally as "Clickeyville."

One of the biggest early challenges was overhauling the game’s dialogue system. Instead of having little blocks of text hovering over character heads, ZeniMax wanted to bring the camera in tight on the faces of non-player characters. The team added a branching dialogue tree, which meant writing thousands of lines of new dialogue. Then, it had to get voice work done by dozens of actors, something which Firor said was originally outside the scope of the original project.

The Elder Scrolls Online circa 2013.

BEST IN SHOW

Even though they had barely scratched the surface of the proposed changes, by June of 2013 the team members at ZeniMax had a dramatically different game than they had started with. Gone were the dated, garish colors and cartoonish physical proportions of the avatars.

ESO was leaner, and felt more like the classic single-player experiences Elder Scrolls fans had grown to love.

And so Firor and his team took a build to E3 and held their breath.

"We had already had a lot of art done by that point," Firor said. "We already had a lot of world development done, so we really needed to finish changing the art style a little bit to make it a little darker and grittier. It was still a little too bright.

"We showed the game off to the E3 judges, and we had a very good showing."

That’s an understatement. Critics voted

The Elder Scrolls Online the best role-playing game at E3 2013.

"We were confident," Firor said. "And with good reason. But maybe we shouldn’t have been so confident."

The next major phase was a proper beta test, which launched in September 2013. It was, to use Firor’s phrasing, a "true beta." The goal was to break the game, early and often. But fans weren’t expecting that.

"In the beta, we basically let people play for a while, and then we would let too many people into the game — on purpose — and the servers would crash."

While the ZeniMax engineering team had intended to invite a bunch of guinea pigs in to quietly stress test its megaservers behind closed doors, players just wanted to be left alone to play. It was another example of his team misjudging what fans expected from

ESO and, Firor said, a decision that haunts him to this day. But he still stands by his team’s decision.

"We only had one chance to launch the game," he said, "and it had to be stable. And, as it turns out, at launch it was pretty stable. But we had burned a lot of our bridges with a lot of our beta players.

"When you hear the term beta these days, players are thinking that this game must be ready for release and we just want some people to come play it. It was not fun for them throughout the days of the beta. A lot of the players were under non-disclosure agreements at the time, but we had internal bulletin boards and they were just full of hate. All we heard was, ‘Your game is not ready for launch. It crashes all the time.’ Even though all the communications we had with them was along the lines of, ‘Welcome to the beta. By the way, this is a stress test. The game will crash

many times. We are going to be intentionally messing with it.’

"INTERNAL BULLETIN BOARDS ... WERE JUST FULL OF HATE."

"But that does not sink in when you’re talking to 100,000 people on a message board," That’s how many players his team needed to invite to get 2,500 of them online at the same time for testing.

"You just lose connection with that big of a population."

Firor blames the bad private beta experience in late 2013 for giving

ESO a lasting bad reputation — a reputation for bugs, crashes and poor performance. It was a pre-conceived notion that colored the next, even larger beta in early 2014.

That second beta had more than

five million people register to play it.

"Once a story gets out, it’s a kind of collective wisdom," Firor said. "Then it becomes the truth, and that’s just the way that it works. When we went to our next beta, and we actually got up to well over over 150,000 people on servers at one time, that was the one where we wanted to see what our real maximum player count was.

"We got them all in, and it crashed. And that was the last one that was under NDA, and as soon as we dropped the NDA, people were saying online, ‘Hey, it's OK. The game itself is OK, but boy is it unstable.’ People picked up on that when they began writing reviews, or just talking about it on the internet."

In reality though, the ZeniMax megaservers worked. And they worked well. It was a strong foundation, but it had cost the team goodwill in order to build it.

An map of Tamriel

THE DAM BREAKS

When the game finally launched, at first on Windows PC in April 2014, there were bugs. But, Firor said, they were completely different bugs than his team encountered during the beta.

Some of them were inside the game’s social systems, like chat and account management. By having such a large beta group, the team at ZeniMax let in more than a few bad apples. Bot makers and gold farmers ran rampant on day one, gobbling up resources at an incredible rate until their characters were banned, and then simply spooling up another character. In their down time, they polluted regional chat with spam messages for illegal offers. It took a while to get them under control, but meanwhile the quest progression system began to break down.

All over

ESO, players were unable to complete key objectives, which prevented them from moving into certain regions of the game world. Players began to pile up, like water rising against a dam in a river. But the dam, in this instance, was infinitely high. With no way over the top of broken quests, players fanned out looking to glitch their way through.

"When those problems started happening," Firor said, "players would just move around the game in ways that we weren't envisioning, looking for things to do. And then the bug would show up in other places. Players weren’t moving through the game in the way that we had envisioned. We had that bug fixed in three weeks, but that was a big problem and we should never have launched with it."

"THAT WAS A BIG PROBLEM AND WE SHOULD NEVER HAVE LAUNCHED WITH IT."

For a while, teams of ZeniMax customer service agents — Firor won’t say how many — headed into the game world to find players individually, and manually move them around the bug and over the dam. Eventually, the bug was squashed and the team moved on to other issues.

Otherwise, Firor said, the launch of

ESO was relatively smooth. The megaservers performed well. Even with the pernicious quest progression bug, things like player population balancing, login queues and other quirks of the MMO genre were not outside the norm at launch. But

ESO already had a bad reputation which had been earned, perhaps unjustly, during the beta.

Firor blames

ESO’s review scores on that reputation more than anything else. The PC version of the game stands at 71

on Metacritic. What his team found strange was the distribution of those scores.

"Our reviews were crazy," Firor said. "If you go back and look at the reviews during that period they were ranged from 50 all the way to 90. People were all over the place. The problem that we had trying to parse this ... was no two reviewers actually picked the same things to knock us on. One would say that the audio is the best they had ever heard in a game, and then the next guy would say that the audio is terrible and the whole team should be fired. So it was across the board.

"Reviewers knew something was missing but they couldn't put their fingers on what it was."

The Elder Scrolls Online, circa 2016.

HOLD THE LINE

With the console launch at least a year away, the team came together with ZeniMax management. A decision had to be made on how to proceed ... or if they even

should proceed.

"We've all been in the industry for a long time here," Firor said, referring to himself and the read of the ZeniMax Online leadership in 2014. "One option was to cut and run. But when we talked to our senior management, that was never an option. They came to us and said, ‘It's not great. So what are you going to do about it?’"

It would take a lot of hard work, but after weeks of putting out fires inside the PC version of the game, Firor and the team knew one thing for certain — people were enjoying

ESO. While ZeniMax declined to share figures for this story, Firor said there was a substantial number of players spending a lot of time with the game.

"We had a dedicated core of people playing the hell out of the game, and they

loved it," Firor said. "

ESO was solid at its core, and we had the metrics backing that up. ... If the game was awful, that just would not happen."

And, thanks to the success of

Skyrim, there were even more players waiting to play it on modern consoles.

"WE HAD A SECOND CHANCE, AND NOT EVERY GAME GETS A SECOND CHANCE."

"We had a second chance," Firor said, "and not every game gets a second chance.

"Management looked at us and said, ‘You're the experts. You made the game and you know what’s wrong. Give us a plan, let's go over it and let's make sure it's the right thing to do.’"

With the PC version running more or less optimally, Firor said that ZeniMax focused on finishing the console version, all the while making the game more inviting for console players.

First, the team focused on making players’ actions feel more meaningful. Rather than letting players just hit a button and watch animations go off and health meters rise or fall, Firor and his team focused on player agency.

Combat was sped up and animations were trimmed down, all in the hope of shaving a few hundred milliseconds off the time between when a player hit a button and their character moved in the game. It doesn’t sound like much, but Firor says it was a months-long, cross-disciplinary effort that pulled in groups of artists and designers from across the entire development team. The result was a first-person fighting experience more on par with

Skyrim.

Next, the team revamped the facial animation system. When

ESO launched on PC, NPCs were little more than "sock puppets," said Firor, so his team went to work rebuilding them to be more expressive and lifelike. By the time the game was ready for PlayStation 4 and Xbox One,

ESO’s fully-voiced digital actors grinned, scowled and emoted in ways that hadn’t been possible just a few months before.

Changes made for the console game regularly fed back into the PC version, something that Firor said helped make the experience better for every player.

The Elder Scrolls Online, circa 2016

ANY GIVEN SUNDAS

After a six-month delay,

announced in December 2014, there was one major change that happened on the way to the console launch. On March 17,

The Elder Scrolls Online got a new name —

The Elder Scrolls Online: Tamriel Unlimited.

That same day, it also dropped its subscription model.

Players can still pay a monthly fee, but instead of allowing access to a game they already paid full price for, that membership gives them in-game currency — called crowns — to spend on things like cosmetic items and mounts. It now also offers access to all of the game’s content expansions, including new regions of Tamriel.

DLC is still available for purchase a la carte, but for subscribers it’s all completely free.

"I was one of the big proponents of that change," Hines said. "My thought was ... that if we didn’t require it, but we made it cool, that we would get a ton of subscribers. People would pay the fee just because they could, as opposed to us forcing them to pay it.

"Just like in the Elder Scrolls games themselves, players wanted to be able to choose. They just didn’t want to

have to do something."

ACTIVE PLAYERS ON PC NEARLY TRIPLED OVERNIGHT.

The gambit worked. On March 17, 2015

ESO had the same average number of players that it had had for most of the year. The next day, it had nearly three times that number.

"Our PC concurrency between the 17th and the 18th of March tripled," said director Matt Firor. "We didn't get a huge increase in sales on March 17th, but we got a lot of the people that used to play on PC to come back."

Even more importantly than a quick surge of players, people began to stick around. Again, Firor won’t say by how much, but the active player base began to grow. As it grew, review scores began to improve.

"One of the funny stories that I tell is that our Steam scores ... went from mostly negative, because people hated the subscription model, to mostly positive in about six weeks," Firor said. "If you did the numbers of what the review scores had to be to drag that number back up there, most of them were positive and in the 90s to drag the overall score back up that far."

Three months later, in June 2015,

ESO finally launched on PlayStation 4 and Xbox One. That’s when the big payoff finally came for Zenimax Online.

"All the servers completely melted at 12:01 am on launch day," Firor said. "Our North American server went down for fours hours, because so many more people were playing then we had thought were going to be playing."

"WE HAD NEARLY HALF A MILLION PEOPLE SIMULTANEOUSLY ON THE SYSTEM. IT WAS INSANE."

Zenimax was finally seeing the benefit of

Skyrim’s success as a massive wave of console players satisfied their urge for a new Elder Scrolls experience.

"Our forecasts were way too low," Firor said. "There was a lot of pent-up demand for the game. We had 235,000 people playing simultaneously on our two megaservers, and we had over 200,000 people in queues. So we had nearly half a million people simultaneously on the system. It was insane."

Today, more than a year after the console launch, the

ESO player base is roughly split into thirds. Thirty percent of the total population of the game exists on each of its major platforms — PlayStation 4, Windows PC/Mac and Xbox One.

All told,

over seven million players have tried the game. We pushed Zenimax to define that number more precisely. All it would say is that excludes beta players and free weekends on consoles and represents the number of actual players who have played the game.

Firor and his team consider it a massive achievement, and a testament to the health of the game.

The Elder Scrolls Online: Tamriel Unlimited launched One Tamriel on PC on Oct. 5, 2016. It will arrive on consoles on Oct. 18.

THE LONG MARCH

Even after changing the subscription model, even after the successful console launch, the work of improving

ESO — of bringing about the changes Firor and his team had envisioned way back in 2012 — still wasn’t finished.

"The way I always say this is, we worked hard for a year to launch the console versions of the game," Firor said. "Along the way, we made the game tons better. The game got better reviews, and we also changed the revenue model. But the list of things we came up with to add to the game got more and more interesting because, broadly speaking, it wasn’t items on the list. They were statements.

"One of our statements was that the game was just not broad enough. If you get into a specific system, it's very deep and that's cool. But the overall experience is not broad."

Firor said that for all the work his team had done,

ESO still didn’t keep players busy enough. You could go on quests and raid for high-end loot, but the game was still missing the kind of open-ended gameplay and lavish world building that was the hallmark of an Elder Scrolls game.

"When players log in, they could have three things that they could be doing," he said. "It should have probably been more like eight or nine things they could have been doing. I should just be able to go and steal things. I can do that in

Skyrim. I should be able to go and organically take down a group boss, maybe with some friends. The game felt a little too much like if players weren’t on a quest with someone, or being told a story or in a dungeon, there was nothing to do."

"THE GAME WAS JUST NOT BROAD ENOUGH."

The solution, Firor said, was to continuously build out new systems, new opportunities for open-world play that players could add to their in-game to-do lists, and to supplement that with massive new additions to the game world.

One of the first improvements was a new justice system. It took the many thousands of items in the game world and flagged them as being owned by certain NPCs. Just like in the single-player games, players in

ESO could finally make a living as a thief. A network of fences scattered throughout Tamriel limited the amount of goods players could sell off as not to destabilize the in-game economy, and guards all over the world were tasked with enforcing the law if anyone was caught stealing.

Another addition was a champion system, which allowed high-level players to further improve their skills with passive abilities. In

Skyrim, one of the end-game goals is the mastery of a single skillset, represented by lighting up all the stars in a constellation.

ESO’s champion system was a corollary to those constellations, and allowed for hardcore players to evolve their characters into an epic new tier.

New content rolled out at a grueling pace.

The Imperial City brought Cyrodiil, the hub zone from

Oblivion, into

ESO. Walking along its cobbled streets was meant to evoke nostalgia in console players, but it also contained massive new dungeons in the sewers below. Later came

Thieves Guild and

Dark Brotherhood, which added fan favorite questlines and occupations to the game

A tour of Orsinium, from The Elder Scrolls Online: Tamriel Unlimited circa 2016

ONE TAMRIEL

Orsinium, Firor said, is probably his team’s crowning achievement. Not only did it provide some of the most narratively rich quests in the game, Firor thinks it was one of the most technically challenging pieces of content for his team to make.

It’s also one of the most beautiful.

Orsinium is the name of the Orc race’s ancestral capital city, long fallen into disrepair. The city itself is placed inside of a dramatic, snow-capped mountain valley and its towers rise to heights the developers couldn’t even dream of when the game was initially launched.

Players who travel there are offered a quest line that allows them to rebuild the Orsinium, which visibly changes over the course of the adventure. The tools needed to create that kind of environmental spectacle, Firor said, fundamentally changed what his team was able to create inside the game world.

"It's a very evocative story," Firor said. "But in the end, you are the one rebuilding the entire city. As you do the quest, the city gets remade until you're done and all the cranes are gone and the walls are perfect.

"Orsinium was actually started after the PC launch. We learned a lot from the content mistakes and tweaks that we had to make over the course of 2015, and we had to put that knowledge into Orsinium.

But the biggest technical hurdle in

Orsinium, Firor said, was the first implementation of level scaling. Low-level characters as well as high-level characters could travel there as soon as the DLC was released and participate in the same activities together. Players and enemies alike were altered in the background, imperceptibly to players, to make encounters challenging but not unfair.

In many ways,

Orsinium proved that

One Tamriel — an update that cuts against the grain of the traditional MMO model — was even possible.

One Tamriel removes all level restrictions from the game, allowing players to tour the game world at their leisure. It also removes the alliance restrictions that frustrated so many, preventing them from playing together with their friends.

The Elder Scrolls Online: Tamriel Unlimited circa 2016

"

One Tamriel is divorcing the idea of content level from player level," Firor said. "Remember

Oblivion when you walked out to the Imperial sewers for the first time? You thought, ‘I can go anywhere!’ Well now you finally can."

The background changes have been difficult and complex. Dynamic systems had to be created in order to make low-level players more powerful, and also to make high-level enemies less deadly. New loot tables, and new loot, have had to be generated for each of the game’s more than 300,000 enemies. Rare items and item sets have been regionalized, meaning that what a character looks like and how they fight is as much a factor of where they’ve been as how long they’ve played.

One Tamriel wouldn’t have been possible without the success of Orsinium, and neither could have even been conceived of if Zenimax Online hadn’t sat down in 2012, in the wake of

Skyrim, and made a bold plan to change

ESO.

Along the way, Firor said, the process has also changed his own conception of what an MMO can be.

"In the year 2014, and especially in the year 2016, what is an MMO?" he asked. "It's a rhetorical question of course. An MMO is, at this point, pretty much a technology and not to a game. When people

say MMO, what they really

mean is

EverQuest circa 2004.

World of Warcraft.

Dark Age of Camelot. Games that have a very specific set of features.

"AT IT'S HEART,

ESO REALLY IS A ROLE-PLAYING GAME."

"I would say that

Destiny is just as much an MMO as any other game that has ever been made. But it's not what you would think of as a traditional MMO. And we were in that category when we started

ESO. We were making a traditional MMO. But we ended up making something very different.

"At it's heart,

ESO really is a role-playing game. It just has all these other players in it. But if you call it an MMO, then a lot of the baggage comes in from 2004 which may or may not apply any more. ... It all comes from these arbitrary design decisions that we made so early on. Why can't I walk across two-thirds of the world? Because the design we made didn't set it up that way, which in 2016 is not necessarily the right answer."

"Now a player can finally go and do what they want to do, and have fun in an Elder Scrolls world and not feel tied to an arbitrary design decision and be able to play with one another. That's really what

One Tamriel is all about."

Firor and his team have already launched the update for PC players, and so far fan response seems to be good. But two thirds of their player base will be seeing the update for the first time next week.

Only time will tell if

One Tamriel provides the same kind of boost the change in the revenue model did.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7278505/DLC_ALLFinal.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/assets/3680835/bethesda_vgx.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7273161/Screenshot_20110628_142942.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7273133/Screenshot_20100525_093158.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7273235/eso_2013.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7273241/award.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7274505/OneTamriel_Map.png)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7273347/GroupBoss1Final.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7273377/DB_GoldCoastZoneCompletionFinal.png)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7273513/AdventureWithoutLimitsFinal.png)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7274247/RaceNameChangeFinal.png)