Of all the things to come out of the

golden age of pulp science fiction, the strange pseudo-religious cult of Scientology has been among the least welcome.

The man who would found the cult was a charismatic fabulist named L. Ron Hubbard. After dropping out of university at age 21 in 1932, he resolved to make his living by doing what he most enjoyed: telling tall tales. Luckily, he lived in New York City, the heart of the pulp-publishing industry.

Hubbard proved unusually prolific even by the standards of the pulps, churning out multiple stories every week. He wrote in any genre that paid, from westerns to mysteries, but he showed a particular affinity for science fiction. Although his prose was dubious, his stories had a gonzo over-the-top energy about them that soon made his name a significant draw on magazine covers. One might say that Hubbard was the pulpiest of pulp writers. While authors like Isaac Asimov, Jack Williamson, and

Ray Bradbury sometimes defied the lurid blurbs and cover art that accompanied their work to present stories of surprising thoughtfulness and texture, an L. Ron Hubbard story was exactly what it appeared to be on the surface: all flashing ray guns, whizzing spaceships, and heaving female bosoms. And that sort of thing, of course, was exactly what so many of the eager adolescents boys who bought the pulps were looking for.

The beginning of the Second World War marked the end of the first heyday of the pulps, as most of their writers were inducted into one form or another of military service. Hubbard parlayed a peacetime reserve commission into a regular officer’s posting in the Navy, but his wartime record proved a decidedly inglorious one. He was given the command of a submarine chaser in 1943, only to be relieved of that duty within a month for using a populated island off the coast of Mexico for gunnery practice. He never came close to meeting the enemy in any of his postings, which saw him mostly sitting behind desks in port-side offices.

After the war, he made his way to Hollywood, where he became involved for some time with a semi-serious cult that embraced Thelema,

Aleister Crowley’s egoistic and hedonistic take on spiritualism. Here he learned hypnotism; indeed, the group became something of a training ground for his future as a cult leader. He moved back to New York City after a year or so and resumed writing for the pulp market, which was now enjoying a postwar second wind. But he already had grander schemes in mind.

In the December 1949 issue of

Astounding, the most prestigious science-fiction magazine in the business, the already legendary editor John W. Campbell made the first mention in print of Dianetics, Hubbard’s new “science of the mind.” “This is not a hoax,” he wrote. “Its power is almost unbelievable.” Campbell hardly had a reputation for gullibility, and his willingness to take every word that fell from Hubbard’s lips on this subject as gospel truth became a source of considerable wonder among his stable of more skeptical writers. Nevertheless, believe in Dianetics he did, turning his magazine into a soapbox for Hubbard’s vaguely Freud-like — but, as Hubbard would be the first to point out, not

Freudian — theories about an “analytical mind” and a “reactive mind,” the latter being the subconscious product of often unremembered traumas that constantly undermined one’s attempts to be one’s best self. The only way to become a “Clear” — i.e., free of the reactive mind’s toxic influence — was to undergo a series of “audits” aimed at locating and rooting out the hidden traumas, or “engrams,” as Hubbard called them.

Hubbard would teach ordinary people to become auditors, and together they would become the vanguard of a new, Clear society free of most current worldly woes. Every medical problem from near-sightedness to cancer, Hubbard claimed, could be cured by purging the reactive mind that was their wellspring. Ditto societal problems. What were wars, after all, but products of the mass reactive-mind psychosis?

Published in book form in May of 1950, Dianetics was roundly condemned from the start by professional psychologists, who saw it, reasonably enough, as unmoored to any shred of real scientific evidence and potentially dangerous to the mental health of its more vulnerable practitioners. This rejection spawned in Hubbard a lifelong hatred of traditional psychology; he would pass the sentiment on to the cult he would found, among whom it remains a fundamental tenet to this day.

Nonetheless, Dianetics enjoyed a substantial degree of mainstream attention and even acceptance for a few years. For war veterans in particular, dealing with an overtaxed Veterans Administration that still had little understanding of post-traumatic-stress disorders, its promise of a quick fix for their pain was very appealing indeed.

Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health climbed high on the bestseller lists, and Hubbard, suddenly making more money than he had ever seen in his life, busied himself with making still more of it, by setting up a nationwide network of Dianetic Research Foundations peddling auditing sessions for neophytes and auditing courses for those who wished to make the leap from patient to therapist. In terms of sheer numbers of people actively engaging with his ideas, the early 1950s was by far the most successful period of Hubbard’s life.

But it wasn’t to last. As it became clear that Dianetics wasn’t actually allowing people to throw away their eyeglasses, much less curing cancer, the wave of earnest interest collapsed as quickly as it had built, to be replaced by scorn and ridicule. The research foundations went bankrupt one by one. Meanwhile John W. Campbell’s magazine never recovered from its editor’s tryst with pseudo-science. It gradually lost its status as science fiction’s most prestigious journal, declining into near irrelevance for the next generation of up-and-coming writers and readers.

With his Dianetics empire crumbling around him, Hubbard sent a telegram to his remaining loyalists announcing “important new material.” And with that material, at a stroke, he turned the pseudo-science of Dianetics into the pseudo-religion of Scientology. Spinning a yarn that he might once have sold to the pulps, he told of a race of immortal beings, existing outside the bounds of space and time, known as the Thetans. (The similarity of the name to Crowley’s Thelema was perhaps telling.) The Thetans had created the universe on a lark, only to get themselves trapped within it. Now, they constituted the souls of human beings, but had forgotten their true nature. But never fear: Hubbard could help a person unlock her inner Thetan, thereby attaining superpowers the likes of which immortality was only the beginning. The first official chapter of his Church of Scientology was founded on February 18, 1954.

Whereas Dianetics had aimed to clear the whole world as quickly as possible, Scientology was for a small group of chosen ones able to recognize its spiritual potency. The true believers lumped everyone else in the world — especially those who had been exposed to Scientology and had chosen to reject it — under the contemptuous category of “wog.” In other words — to put it into terms a cynic can understand — Hubbard had switched from extracting a little bit of money from each of many people to extracting a whole lot of money from each of relatively few people. Early Scientology courses were cheap or even free, but progressing down the “Bridge to Total Freedom” required paying more and more for each successive step. Soon the most dedicated members were giving virtually everything they earned to the church. And it never ended; there was always a further, even more expensive level of enlightenment to be achieved, courtesy of a founder who could always dash one off whenever it was needed. His training with the pulps, it seemed, was still paying dividends.

The full story of the Church of Scientology is as complicated as it is bizarre, encompassing pitched battles with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Internal Revenue Service, and many a foreign government, along with a culture of secrecy and paranoia that only got more pronounced from year to year. The church’s history intersects with that of late-20th-century history more generally in often surprising, usually sinister ways. For example, Charles Manson flirted with Scientology while in prison, and later applied some of the techniques of control and manipulation he had learned from it when he started The Family, his own murderous cult of personality.

Perhaps the strangest period of Scientology was that spanning from 1966 to 1975, during which Hubbard, still nursing unrequited dreams of naval heroism, sailed a “fleet” of dilapidated ships, crewed by enthusiastic and comely if dangerously unskilled young followers, all over the world. Much of the current church’s symbology and iconography, such as the “Sea Org” which serves as a sort of elite honor guard for its most precious people and secrets, still dates from this period, as does a policy of harsh paramilitary discipline. For Scientology, claimed Hubbard, was now at war with an outside world bent on destroying it. Journalists and psychologists were its greatest enemies of all, to be shown no mercy whatsoever.

Scientology could and did ruin the lives of its critics. The classic cautionary tale became that of the investigative journalist Paulette Cooper, who in 1971 published an extremely critical history of L. Ron Hubbard and his church under the title of

The Scandal of Scientology. She was subjected to a years-long campaign of abuse, taking the form of some twenty separate lawsuits, along with constant harassing phone calls and even break-ins to her apartment. Scientologists wrote her phone number on bathroom walls (“For a good time, call…”), passed out fliers in her neighborhood peddling her alleged services as a prostitute, and sent bomb threats to their own church in her name; these they then referred to the FBI, leaving Cooper to battle criminal charges with a sentence of up to fifteen years in prison. “For months, my anxiety was so terrible I could taste it in my throat,” Cooper says. “I could barely write, and my bills, especially legal ones, kept mounting. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t sleep.”

L. Ron Hubbard himself withdrew even further from public view when his declining health forced him to return to land in 1975. There was great concern within the church that he might soon be arrested on charges of fraud and tax evasion — indeed, this had been one of Hubbard’s ostensible motivations for taking to the sea in the first place — but there was also a degree of embarrassment that the pot-bellied old man was anything but a poster child for the perfect physical fitness and eternal youth he had so long promised his followers. He thus spent the last few years of his life in complete isolation at secret locations, apparently being controlled by more than he continued to control the church’s senior leadership.

He died — or, as the church put it, “moved forward to his next level of research” — on January 27, 1986. By that time, a mad struggle for control of the organization he had founded had been underway for years, and had largely been won already by one David Miscavige, who was still just 25 years old at the time of Hubbard’s death. He consolidated his power in the aftermath, and remains in charge to this day of an organization that is more insular and secretive than ever.

Miscavige’s most far-reaching innovation, which he began to implement even well before Hubbard’s death, was the so-called “celebrity strategy.” Eager to attract prominent people with enviable lifestyles for promotional purposes, Miscavige opened a special “Celebrity Centre” in Hollywood. It boasted, as the journalist Janet Reitman describes it, “39 hotel rooms, several theaters and performance spaces, a screening room, an upscale French restaurant, a casual bistro and coffee bar, tennis courts, and an exercise room and spa.”

The profession of actor may appear glamorous from the outside, but it can be almost unbelievably brutal from the inside, even for those who have achieved a degree of success. In this respect, the profession defies direct comparison to almost any other. An actor must face constant, detailed, explicit critiques of her appearance, her voice, her way of holding herself and moving — in short, of her very

being. Thus Scientology found in Hollywood a receptive audience for the doctrines of personal empowerment and self-belief that it had always used to lure new members into the fold. The movie stars John Travolta and Tom Cruise became the most visible celebrity faces of Scientology, but it spread its tendrils throughout the entertainment industry, snaring countless other names both recognizable and obscure — for in Hollywood, today’s obscurity may be tommorow’s marque name, as Miscavige understood very well. Better, then, to sign them

all up.

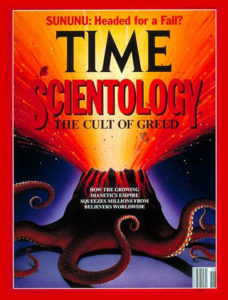

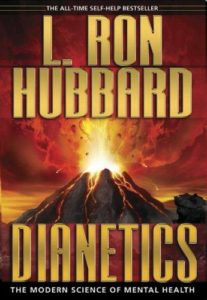

Since the publication of Paulette Cooper’s book in 1971, most journalists, well aware of the pain said book had brought upon its author, had chosen to keep their distance from the church. But finally, in its issue dated May 6, 1991,

Time magazine ran the first lengthy exposé of Scientology in a generation, under the byline of one very brave reporter named Richard Behar. The hook for his piece was the tragic story of Noah Lottick, a “normal, happy” 24-year-old who had given all of his money to the church in the span of seven months, then committed suicide by jumping from a tenth-story window. “We thought Scientology was something like Dale Carnegie,” said the young man’s grieving father. “I now believe it’s a school for psychopaths. Their so-called therapies are manipulations. They take the best and the brightest people and destroy them.”

Other affecting personal tragedies were sprinkled amidst the article’s accusations of financial malpractice, eavesdropping, and harassment, all products of what Behar labelled “a thriving cult of greed and power,” worthy of comparison to the Mafia. Like so many cults, the Scientologists showed a marked tendency to prey upon the most vulnerable:

Harriet Baker learned the hard way about Scientology’s business of selling religion. When Baker, 73, lost her husband to cancer, a Scientologist turned up at her Los Angeles home peddling a $1300 auditing package to cure her grief. Some $15,000 later, the Scientologists discovered that her house was debt free. They arranged a $45,000 mortgage, which they pressured her to tap for more auditing until Baker’s children helped their mother snap out of her daze. Last June, Baker demanded a $27,000 refund for unused services, prompting two cult members to show up at her door unannounced to interrogate her. Baker never got the money and, financially strapped, was forced to sell her house in September.

Predictably, the Church of Scientology sued

Time for libel. It would take almost ten years for the magazine to win a final legal victory, on the basis that everything reported in the story was substantially accurate.

The timing of this article is highly significant for our purposes: it was read by Richard Garriott, who had recently decided that

Ultima VII should have a “real bad guy” as the antagonist for the first time since

Ultima III. “Richard came up with the initial idea,” remembers Raymond Benson, the game’s head writer, “but I’m pretty sure I came up with everything the Fellowship did, as well as their various tenets and beliefs.”

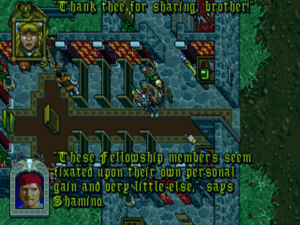

Of all the many and varied threads taken up by

Ultima VII, that of the Fellowship is the most thoroughgoing. This isn’t surprising on the face of it, given how important the Fellowship is to the game’s overarching plot. What is surprising, however, is how subtle and even wise — not words I use often in connection with CRPGs, believe me! — the game’s depiction of the cult really is. Taken as a whole, the Fellowship’s practices demonstrate a canny understanding of how non-stupid people can be convinced to believe in really stupid things, and how they can be convinced — or coerced — to dedicate their lives to them. Indeed, although the direct inspiration for the Fellowship is Scientology, the understanding of cultish behavior which

Ultima VII demonstrates applies equally to many of them. “It wasn’t just Scientology we were knocking,” says Benson, “but all kinds of religious cults.”

Separated at birth? L. Ron Hubbard…

..and Batlin.

The Guardian, the disembodied spirit of evil who’s the prime motivator behind the Fellowship, prefers to hide behind the scenes. The cult’s ostensible founder and public face is instead an unprepossessing fellow named Batlin, who carefully cultivates an everyman persona. In the

Book of the Fellowship included with the game — quite possibly the only game manual ever to be written from the point of view of the eventual villain — he speaks of his “humble hope that these words may be for thee a dawning, or at least, a type of awakening.” He is a “traveller” just like you are, who has stumbled upon a form of enlightenment, and he “would very much appreciate sharing the rewards with you.”

This is the modern face of the cult leader, couched in a superficial aura of approachability. Hubbard too dressed casually and encouraged those around him to call him “Ron.” Yet it is indeed a facade; the leader is in fact

not an everyman. The affectation of humility is an act, meant to demonstrate the leader’s superior character. He may be a fellow traveler, but the fact remains that he became enlightened while the rest of the world did not; he is, by definition,

special, as any cultist who takes his affectation of humility too seriously and challenges his edicts in any way will quickly learn. The Fellowship, like Scientology, is as hierarchical an organization as ever existed.

Still, the impression of casual normality conveyed by the leader is essential to the recruitment process. No one consciously signs up for a cult; people are captured by an innocuous pitch for self-improvement that seems to offer considerable rewards for little investment of time, energy, or money. It’s only after the recruit is inside that the balance begins to subtly shift and the cult begins to demand more and more of all three.

Scientology has studied the recruitment process long and hard, adopting approaches that lean more on theories of marketing than religion. The first pitch says nothing about Thetans; it restricts itself to the relatively more grounded psuedo-science of Dianetics, described as a self-help program that helps one to live a more effective life. The corporate banality of it all smacks of nothing so much as a dodgy vacation-timeshare pitch. In her book on Scientology, Janet Reitman describes her own first encounter with the church in New York City:

At various times during the year, clusters of attractive young men and women are posted on street corners, where they offer free “stress tests” or hand out fliers. Ranging in age from the late teens to the early twenties, they are dressed as conservatively as young bank executives.

On a hot July morning several years ago, I was approached by one of these clear-eyed young men. “Hi!” he said, with a smile. “Do you have a minute?” He introduced himself as Emmett. “We’re showing a film down the street,” he said, casually pulling a glossy, postcard-sized flier from the stack he held in his hand. “It’s about Dianetics — ever heard of it?”

I was escorted to a small screening room to watch the free introductory film. After the film, a woman came into the screening room and told me that she’d like me to fill out a questionnaire. She began her pitch gently. Laurie delivered a soft sell for Scientology’s “introductory package”: a four-hour seminar and twelve hours of Dianetics auditing, a form of consuling that cost $50. “You don’t have to do it,” Laurie said. “It’s just something I get the feeling might help you.” She patted my arm.

That initial request for $50 will grow in a remarkably short time to hundreds, then thousands of dollars, all absolutely required for one to reach the coveted status of Clear and commune with one’s inner Thetan.

The Fellowship recruitment process works much the same way. Every town you visit in Britannia has a Fellowship Hall — or, as it is known in the cult’s corporatese, a “Recreational Facility and Learning Center.” (One of the prime innovations of Scientology, and apparently of the Fellowship as well, was to turn religion into a corporate franchise operation.) While the town themselves are diverse, every Fellowship Hall looks the same, right down to the

Book of the Fellowship standing in a place of honor just inside each of their doorways. (“Books by L. Ron Hubbard lined the walls,” notes Reitman of her Scientology recruitment experience, “as did black-and-white photos of the man.”)

The people hanging about the Fellowship Halls all casually bring up the “Triad of Inner Strength”: “Strive For Unity,” “Trust Thy Brother,” “Worthiness Precedes Reward.” These three principles hardly represent major advances in moral philosophy; they simply say that people should work together whenever possible, should trust in the basic goodness of their fellow humans, and should do good work for the satisfaction of the work itself, understanding that external rewards will come of themselves in due course. The Triad of Inner Strength, in other words, is something most of us learned in grade school.

And yet, banally harmless though it sounds at first blush, the Triad of Inner Strength can all too easily be twisted into something less than benign, as Richard Garriott noted in an interview with Caroline Spector from around the time of

Ultima VII‘s release:

And so the Fellowship is this cult religion that is founded upon three principles. The first is Unity. To work for a better world, we all need to work together. If we work together, we’ll be better. This is your “go out and evangelize and convert them to our beliefs” syndrome.

The next thing after Unity is Worthiness. You should always strive to be worthy of that which you wish to receive. Always try to deserve that which you wish to receive. Which is another way of saying, you get what you deserve. Which means, as far as the Guardian is concerned, if you’ve been bad, he kills you. You obviously got what you deserved.

The third principle is called Trust. If you and I are going to work together in the same organization, like me and my brother Robert, we have to trust each other. If I constantly think that Robert’s going to stab me in the back, I won’t get any work done. We’d be constantly checking on each other, making sure that what we’re telling each other is the truth. So, you have to trust the other members of the Fellowship. If I tell you to carry this box from here to there, don’t ask me what’s in it. Just trust me.

Spector: Trust has a condition on it, though. The condition is that you do whatever I tell you to do without question.

Trust! Just trust me!

Spector: That’s really not trust.

I didn’t say it was really trust. I said that’s the word they use.

In practice, then, the Triad of Inner Strength leaves the members of the Fellowship ripe for all sorts of psychological manipulation. “Strive for Unity” and “Trust Thy Brother” militate against critical thinking among the membership, while “Worthiness Precedes Reward” can be used to justify all sorts of acts which the membership would otherwise view as heinous.

The recruitment pitch of both Scientology and the Fellowship culminates in a much-vaunted but borderline nonsensical personality test. The Scientology version poses questions like “Do you often sing or whistle for the fun of it?” and “Do you sometimes feel that your age is against you (too young or too old)?” The Fellowship’s questions are at least a bit more elaborate, and actually do offer some food for thought in themselves. In fact, they might remind you of some of the questions posed by a certain gypsy fortune teller at the beginning of

Ultima IV.

Thou art feeling depressed right now. Is it more likely because – A: Thou hast disappointed a friend, or B: A friend has disappointed thee?

At a festive gathering thou dost tell a humorous anecdote, and thou dost tell it very well, creating much amusement. Didst thou tell this comedic story because A: thou didst enjoy the response that thou didst receive from thine audience, or B: because thou didst want to please thy friends?

Thou art in a boat with thy betrothed and thy mother. The boat capsizes. In the choppy waters thou canst only save thyself and one other person. Who dost thou save from drowning, A: thy betrothed, or B: thy mother?

(Freud would have had a field day with that last one.)

Of course, whatever answers you give, on either cult’s test, the end result is always the same: you have much potential, but you need the counseling that only Scientology or the Fellowship can provide. (“Thou art a person of strong character, Avatar, but one who is troubled by deep personal problems that prevent thee from achieving thy true potential for greatness.”)

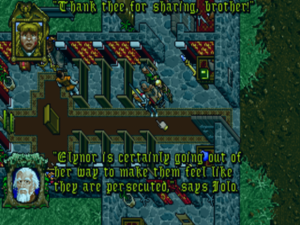

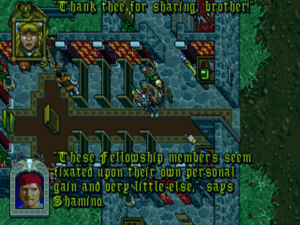

As you wander Britannia talking to Fellowship members — whatever else you can say about Batlin’s cult, it’s achieved a degree of market penetration of which Scientology can only dream — they all parrot the same lines when speaking of the organization. At first, you might be tempted to chalk this up to laziness on the part of the writing team. But later, as you realize that laziness simply isn’t a part of

Ultima VII‘s writerly personality, you realize that it’s been done with purposeful intent, to illustrate the subtle process of brainwashing that occurs once one begins to open oneself to a cult. And as this realization dawns, the parroting that started out as merely annoying begins to take on a sinister quality.

Indeed, the control of language constitutes an important part of a cult’s overall control of its members. Scientology has developed a veritable English dialect all its own, a strange mixture of tech speak, corporate speak, and messianic grandiosity. The word “love” is replaced by “affinity”; the verb “to audit” now means “to listen and compute.” Hubbard’s own writings — Scientology’s version of holy scripture — is the church’s “technology” or “tech.” More ominously, a “suppressive person” is someone who speaks critically of the church, thereby suppressing the truth of Hubbard’s wisdom in herself and in those around her; these people, Scientology’s version of heretics, are fair game for any sort of punishment. One former member and current suppressive person describes Scientology’s manipulation of language thusly:

It’s very, very subtle stuff, changing words and giving them a whole different meaning. It creates an artificial reality. What happens is, this new linguistic system undermines your ability to even monitor your own thoughts because nothing means what it used to mean. I couldn’t believe that I could get taken over like that. I was the most independent-minded idiot that ever walked the planet. But that’s what happened.

The Fellowship too manipulates language for its own ends, preferring convoluted purple prose to directness in such linguistic pillars as the Triad of Inner Strength. The core of the group’s philosophy is “sanguine cognition.” This is just another way of saying “cheerful knowledge,” Batlin helpfully tells us, which rather begs the question why he doesn’t instruct his followers to simply say the latter. The answer is that clear language illuminates its subject, whereas a cult’s mission is always to obscure the sheer banality of its teachings.

The languages of Scientology and the Fellowship alike are meant to highlight their status as

modern belief systems suitable for the modern world. This is important, for any argument for the absolute truth of a religion or life philosophy must carry with it the implied corollary that all

other current religions and life philosophies are false, or at least of lesser utility. Batlin has this to say about the system of virtues that arrived in Britannia at the time of

Ultima IV, more than 200 years ago in the series’s internal chronology:

As one who has followed the Eight Virtues, I know whereof I speak when I say that it is impossible to perfectly live up to them. Even the Avatar was unable to do so continuously and consistently. Can anyone say that they have been honest every moment of their lives? Can anyone say that they are always compassionate, valorous, just, sacrificing, honorable, humble, or spiritual at all times? The philosophy of the Eight Virtues does little more than emphasize our own personal deficiencies. I have met many adherents to the ways of the Virtues who are racked with guilt over what they perceive to be their spiritual failures, for that is what the Virtues are based upon. Having been shown our weaknesses, now is the time to strengthen them. The philosophy of The Fellowship has been created to eradicate the failures from one’s life. It is a philosophy based upon success and it enhances everything that has come before it.

It’s right here that

Ultima VII levels its most subtle but perhaps most important critique of Scientology and similar movements in our own world. A religion, some wag once said, is another person’s cult, and vice versa. I would push back against that notion to the extent that the great religions of the world, irregardless of their claim to objective truth, engage with the full scope of the human condition, including its fundamentally tragic nature. Religion engages with failure and weakness at least as much as it does with success and strength; it engages with pain and loss, with aging and death — because, as another wag once said, none of us gets out of this life alive.

So, a true religion grasps that it cannot deny the tragic realities of life, replacing them with some shallow notion of “success,” as if the ineffable mysteries of life were just a series of bullet points on a CV. As Sophocles and Shakespeare understood, much of life is pain, and true spiritual enlightenment is the ability to laugh in spite of that pain, not to deny its existence. True enlightenment requires one to get

outside of one’s self. Scientology and the Fellowship, on the other hand, are egotism masquerading as spirituality.

What can I get out of this? It’s in this way, it seems to me, that they’re most depressingly modern of all.

And yet moral judgments, as the

Ultima series did such a good job of teaching us over the years, are seldom absolute. Me-focused self-help programs doubtless do do many people a great deal of good, as do Scientology and the Fellowship. For decades now, Scientology’s addiction-treatment programs have been recognized, sometimes reluctantly, as among the most effective in the world. The Fellowship too runs homeless shelters and treats serpent-venom addicts (serpent venom apparently being Britannia’s version of cocaine).

Assuming we believe in the notion of people as sovereign individuals, we must give them permission to believe strange things if they wish to do so. And, assuming we believe in the right of free speech, we must give them permission as well to try to convince others of their beliefs — even to try to convince others to join their group and behave as they do. Where do the limits lie? Efforts to outlaw Scientology in some countries of our own world have struck many as overreaching. But, likewise, the organization’s ongoing tax-exempt status in other countries strikes many as a travesty in its own right.

Of course, there are limits to the parallels between Scientology and the Fellowship. At the end of the day, the fact remains that

Ultima VII is a work of genre fiction. Our ingrained media literacy assures that, from the time when we first meet the Fellowship just minutes after starting the game, we know that they can’t possibly be up to anything good. Indeed, it’s almost a comfort to learn that the Fellowship is being directed by a spirit of manifestly bad intent. That’s the sort of thing we know how to deal with as players of CRPGs. By contrast, very few people in our real world — not even cult leaders —

believe themselves to be evil. Evil here is far more subtle, and often occurs in spite of — or sometimes because of — our best intentions. Those who pull the levers of Scientology are not the Guardian —

not disembodied spirits of evil cackling over their nefarious plans — but ordinary humans who, I would guess, honestly feel in their heart of hearts that they’re doing good.

Still, if it’s comfort which those of us who don’t believe Scientology on balance is a force for good are looking for, we can find some in the fact that the church is by all indications a shadow today of what it was at the time of

Ultima VII‘s release. It’s always been damnably difficult to collect hard numbers about the church’s membership at any point in its history, due to its consistent determination to exaggerate its size and influence. Yet, tellingly, even the exaggerations are much smaller today than they were two or three decades ago. Scientology today many have as few as 50,000 active members worldwide, down from a peak of perhaps 500,000 at the time of the

Time magazine article. Even its stranglehold on Hollywood has been considerably weakened, with many of its superstar converts having quietly backed away. Much of the veil of secrecy around the organization has been pierced, and Scientology’s penchant for retaliation against its critics doesn’t have the same silencing effect it once did. Today, tell-all memoirs about “my life in Scientology,” of wildly varying degrees of veracity and luridness, have became a veritable cottage industry in publishing. Their authors have found a form of safety in numbers; when Scientology has so many critics, it’s hard for it to go after each one of them with the old gusto, especially given its current straitened membership roles.

I suspect that Scientology will die out entirely in another generation or three. For all but the people whose lives it ruined (or saved) and those close to said people, it will go down in history as just another kooky cult, another proof of the eternal human penchant to believe weird things and to cede control of their lives to others in the name of those beliefs. Even as Scientology slowly dies, however, other cult-like belief systems promising love, wealth, and happiness — for a small price — will continue to arise. So, there will never be a shortage of real-world analogues for the Fellowship. Sadly,

Ultima VII‘s claim to thematic relevance is never likely to be in doubt.

(

Sources: the books

Inside Scientology: The Story of America’s Most Secretive Religion by Janet Reitman,

The Scandal of Scientology by Paulette Cooper,

The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction, edited by Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn, and

Ultima: The Avatar Adventures by Rusel DeMaria and Caroline Spector;

Time of May 6 1991. Online sources include online sources include

The Ultima Codex interview with

Raymond Benson, the comprehensive anti-Scientology resource

Operation Clambake, and Frederick Phol’s memories of Hubbard on

The Way the Future Blogs. I owe a special thank you to Hoki-Aamrel, whose

“The Fellowship and the Church of Scientology Compared” served as my spirit guide for researching this article. And my thanks go as well to Peter W., who pointed out in a comment to my previous article that

The Book of the Fellowship may be the only game manual ever written from the point of view of the villain.)

![Have Many Potato [2013] Codex 2013](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_potato2013.png)