RPG Codex Review: ATOM RPG

RPG Codex Review: ATOM RPG

Codex Review - posted by Infinitron on Wed 9 January 2019, 00:09:03

Tags: ATOM RPG; ATOM TeamAgainst all odds, the Atom Team's ATOM RPG has turned out to be one of 2018's most well-received titles and a strong contender for our next RPG of the year. Together with Pathfinder: Kingmaker, it forms the basis of an unexpected Russian RPG Renaissance which we hope will continue. That said, for most people ATOM is probably just a well-executed Fallout homage with some funny memes. Not so for the esteemed bataille however, who identified the game's more esoteric qualities early on. In fact, bataille found ATOM so inspired that she volunteered to review it for us, and did a damn fine job. Here's an excerpt from her literary analysis of the game:

Read the full article: RPG Codex Review: ATOM RPG

First, let’s address the enormous, almost embarrassingly fat elephant in the room before proceeding. The elephant that, before now, I have tried not to glance at too often.

ATOM RPG is exceedingly postmodernist. Actually, I’m fairly certain that it’s the most conventionally postmodernist game I have ever played. Virtually its every aspect is a citation. Its source may be an old Soviet song, a socialist realist film, an actor from the era of Perestroika, a novel written by a dissident, a controversial public figure, an internet meme (yikes), or Fallout. A lot of Fallout. At its most surface level, mechanically and story-wise, ATOM is made of Fallout. It’s got its own Iguana Bob, Richard Grey, The Followers, Rad-X, Vaults, FEV, the BoS, etc. Whether it’s part of the nostalgia motif, a set of homages, or plagiarism is for you to decide, but I think it fits the game’s fever dream feel very well.

It’s not Fallout 2, however, where the elements of its first part were deconstructed to inspect them from a different perspective, but rather a boxful of stuff to play with. In Atom Team’s hands, the borrowed material is clay to create a statue of Lenin with, tear it down, and then make a million other things following the same scenario. It’s playful, lively, and not preachy in any way.

A fair warning, though: like with any PM text, to enjoy ATOM fully, you’ll probably need to play it in Russian and be quite a prestigious Codexer who is no stranger to the 20th century Russian culture. Half the game’s population talks in direct quotes from literature, songs, films, or Soviet clichés. Knowing Sorokin, Yerofeyev, Zinovyev, and Shalamov is a must. Otherwise, you’ll be doomed to giggle at jokes about bigots assuming someone’s hunger level for the 40 to 50 hours required to finish the game. Which is funny enough, I guess, but the game’s main strength lies within the bounds of its literary exercises.

Otradnoye serves as a tutorial village (or as Shady Sands if we were to speak the elephant language), a place designed to be quite moderate in all aspects so as not to overwhelm a beginner. Its secrets are not too obscure; the mutated wildlife is easily dispatched; the quests are simple and easy to follow. The characters are mostly played straight, too.

It’s interesting to note that there are no generic NPCs. Not in Otradnoye, not anywhere else. Every character has their own name, dialogue, and a portrait. Even guards, farmers, and drunkards.

While the ominous implications of this are quite obvious, mostly, ATOM RPG doesn’t degenerate into filler conversations. I’d say only about 5 to 10 percent of all NPCs don’t have anything notable about them. Usually, even if they haven’t got a role in the grander scheme of things, people either have an interesting rumor to share or reference/parody/quote some other Russian text (thus amusing you a bit, hopefully).

Structurally, the conversations are pretty basic. If a character is not involved in a quest of some kind, you’ll only be able to ask them the same four questions. This highlights one somewhat major problem with the game’s dialogues: it seems that some of them have been done absentmindedly, almost on autopilot. More than once I have found myself scratching my head in surprise at some painfully obvious and stupid sentences. A few dozen conversations read (clearly unintentionally) like an unedited stream of consciousness. Again, it’s for you to decide if that’s a dadaist technique that deepens the artistic merit of ATOM or laziness/lack of time on the part of Atom Team.

But when conversations are good, they are witty, often times hilarious, and even touching. Death or misery is rarely the punch line to a joke. The writers are clearly in love with the strange and eccentric but never do they take sides. Be it a hypocritical cult leader, wacky conspiracy theorist, devoted red commissar, or time traveler who is often confused by his own omniscience, all of them are exaggerated to emphasize the qualities that make them tick.

ATOM RPG is exceedingly postmodernist. Actually, I’m fairly certain that it’s the most conventionally postmodernist game I have ever played. Virtually its every aspect is a citation. Its source may be an old Soviet song, a socialist realist film, an actor from the era of Perestroika, a novel written by a dissident, a controversial public figure, an internet meme (yikes), or Fallout. A lot of Fallout. At its most surface level, mechanically and story-wise, ATOM is made of Fallout. It’s got its own Iguana Bob, Richard Grey, The Followers, Rad-X, Vaults, FEV, the BoS, etc. Whether it’s part of the nostalgia motif, a set of homages, or plagiarism is for you to decide, but I think it fits the game’s fever dream feel very well.

It’s not Fallout 2, however, where the elements of its first part were deconstructed to inspect them from a different perspective, but rather a boxful of stuff to play with. In Atom Team’s hands, the borrowed material is clay to create a statue of Lenin with, tear it down, and then make a million other things following the same scenario. It’s playful, lively, and not preachy in any way.

A fair warning, though: like with any PM text, to enjoy ATOM fully, you’ll probably need to play it in Russian and be quite a prestigious Codexer who is no stranger to the 20th century Russian culture. Half the game’s population talks in direct quotes from literature, songs, films, or Soviet clichés. Knowing Sorokin, Yerofeyev, Zinovyev, and Shalamov is a must. Otherwise, you’ll be doomed to giggle at jokes about bigots assuming someone’s hunger level for the 40 to 50 hours required to finish the game. Which is funny enough, I guess, but the game’s main strength lies within the bounds of its literary exercises.

Otradnoye serves as a tutorial village (or as Shady Sands if we were to speak the elephant language), a place designed to be quite moderate in all aspects so as not to overwhelm a beginner. Its secrets are not too obscure; the mutated wildlife is easily dispatched; the quests are simple and easy to follow. The characters are mostly played straight, too.

It’s interesting to note that there are no generic NPCs. Not in Otradnoye, not anywhere else. Every character has their own name, dialogue, and a portrait. Even guards, farmers, and drunkards.

While the ominous implications of this are quite obvious, mostly, ATOM RPG doesn’t degenerate into filler conversations. I’d say only about 5 to 10 percent of all NPCs don’t have anything notable about them. Usually, even if they haven’t got a role in the grander scheme of things, people either have an interesting rumor to share or reference/parody/quote some other Russian text (thus amusing you a bit, hopefully).

Structurally, the conversations are pretty basic. If a character is not involved in a quest of some kind, you’ll only be able to ask them the same four questions. This highlights one somewhat major problem with the game’s dialogues: it seems that some of them have been done absentmindedly, almost on autopilot. More than once I have found myself scratching my head in surprise at some painfully obvious and stupid sentences. A few dozen conversations read (clearly unintentionally) like an unedited stream of consciousness. Again, it’s for you to decide if that’s a dadaist technique that deepens the artistic merit of ATOM or laziness/lack of time on the part of Atom Team.

But when conversations are good, they are witty, often times hilarious, and even touching. Death or misery is rarely the punch line to a joke. The writers are clearly in love with the strange and eccentric but never do they take sides. Be it a hypocritical cult leader, wacky conspiracy theorist, devoted red commissar, or time traveler who is often confused by his own omniscience, all of them are exaggerated to emphasize the qualities that make them tick.

Read the full article: RPG Codex Review: ATOM RPG

[Review by bataille]

A song is much more important

than any material possession:

it brings people together.

And that’s the most difficult and valuable of all.

Andrei Platonov. Doubting Makar.

Context

In 1991, the world saw the end of an era. Despite the common anxiety, not a single atomic bomb brought its demise. Outside: a promise of a bright future, free of The Party's weakened stranglehold; inside: poverty, depression, loss of identity and agency. A year later, necrorealism lost its status as an avantgarde art movement. Literature, film, visual art became disproportionately interested in decay, rot, and the undead. The orthodox eschatology seemingly disappeared, and the posthumous fate of the nation resembled that of a senselessly roaming ghoul. It would take another decade for the polite (if still confused) audience to become engorged with blood enough to move on and start looking for a new beginning. However, in some places, the gloom of the 90s persisted. The apocalypse cult had firmly planted its roots. While the emerging middle class was searching for an identity outside the borders of their native ruin, some people refused to assimilate into an increasingly globalized, homogeneous world. In this state of conscious undeath, they still dream of skeletonized brutalist cities stretching to the horizon and into the dead sun.

Atom Team, a Latvia-based game development studio responsible for ATOM RPG, may very well be of this nostalgic tribe, even if only partially. Having successfully raised $33 000 of $15 000 required to realize their dream of making a Soviet-flavored post-apocalyptic game, they released ATOM RPG in early access at the end of 2017. A little over a year later, the game reached its official 1.0 status to the subaudible fanfares of a dedicated yet somewhat small group of fans that the studio had amassed thanks to their overwhelmingly professional, friendly, and attentive interactions with the community. Even though the game is officially finished, Atom Team has promised to continue expanding and adding fresh content to it. This review is written with versions 1.0-1.04 in mind, hence some parts of the game may change.

Text

Unlike the real world, ATOM’s version of the USSR ended with a bang rather than a whimper. In 1986, a date suspiciously close to the beginning of Perestroika, Cold War came to an abrupt and violent halt. A decades-long rivalry finally ended in mutual nuclear annihilation. The divine broom swept most of the traces of humanity from the planet. However, not even atomic bombs could eradicate life entirely. With the exception of some mutated wildlife, the new and emerging world of post-apocalyptic 90s was not unlike its real-life counterpart: roaming gangs, rotting junkies, lawlessness, and a small number of decent people trying to make it through the anarchy.

The game is set in 2003, in the times when the past is all but forgotten, and the future hasn’t been written yet. Despite the apparent dissolution of the USSR, the denizens of this world still cling to their Soviet identity, even if it hurts their immediate interests. Unbeknownst to them, their desperate struggle to retain a modicum of their former self is assisted by a mysterious military organization called ATOM. With apparent parallels to the Brotherhood of Steel, they are a secretive, well-trained and equipped underground group whose goal is to preserve the Soviet legacy and bring the socialist utopia back to the Wasteland - this time without a mortal enemy to hold them back.

The player is given the role of a member of ATOM who is sent on a dangerous mission of locating a missing expedition led by enigmatic general Morozov. As expected, following his trail leads you to discovering the nature of ATOM, circumstances surrounding the nuclear war, great conspiracies, and possibly a new, greater life for the Wasteland. The most profound mystery of ATOM RPG, undoubtedly, is the [REDACTED] conducted in [REDACTED] to [REDACTED] forever. Better fasten your seatbelt!

This premise is familiar to anyone who has played Fallout, and it’s obvious that it’s been purposefully constructed this way to invoke a strong image of it. On the surface level, ATOM RPG’s script is a remix of Fallout’s story, sure, but it’s not a deconstruction. Many plot elements and world details have been lifted from the immortal post-apocalyptic adventure almost verbatim and then shuffled, seemingly randomly. Some major story points of Fallout have been reduced to gags while others retain their importance. Despite this almost damning characteristic, conceptually, it works in favor of both the ‘nostalgia for Fallout’ angle and creating some fitting imagery for ATOM RPG’s own universe. Without spoiling much, I’ll just say that the word ‘Unity’ becomes frighteningly appropriate in this game...

ATOM RPG’s main menu greets us with a very suitable view: an unknown, apparently military man is walking away from the camera and into a ruined city. The sun is setting (rising?) in the background. We hear a nostalgic Soviet song ‘Blue Cities.’ Its lyrics paint a hazy picture where the past and future flow into each other forming the present. After a while, the man has gone, and the song has ended. Oppressive silence now accompanies the still city.

It becomes clear: ATOM is not a cautionary tale but a reminiscence.

For me, this picture was the first sign that indicated that I had been overly naive in thinking that ATOM RPG would be a mere repaint of Fallout. As it turned out later, its nostalgia longs not for Interplay’s game but for something more precious and unobtainable. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

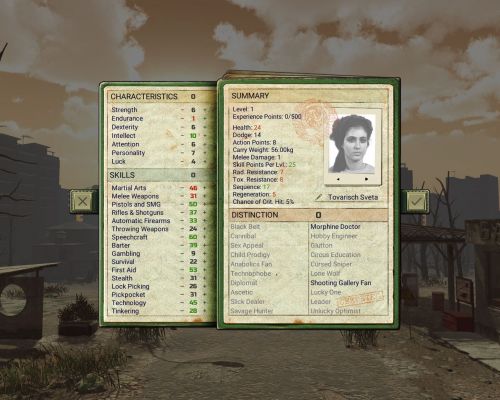

Clicking New Game takes you straight to the character creation screen.

[Attention] It reminds me of an iconic game from the old days.

[Success] Indeed, everything here is as you would expect from a Soviet Post-Apocalyptic Role Playing Game.

The most special and defining part of your character is their characteristics. Each of them affects the numeric values of skills and derived statistics such as Sequence, Health, or Action Points.

Unlike The Game, none of the characteristics can be neglected completely, and all of them often get checked in various in-game situations. Even the ones that don’t get as much use as Strength or Personality have some redeeming qualities that make dumping them yield some undesirable results. For example, endurance, for which there aren’t even half a dozen checks, governs the most important statistic of them all: health; even luck not only affects the outcomes of, supposedly, all skill checks you make, but its high values also allow you to safely bypass some of the most difficult fights in the game (in the world of ATOM RPG, crossing your fingers may prove more deadly for your opposition than a carpet bombing).

However, there are characteristics that are much more useful than the others. The Holy Trinity is Strength, Personality, Intellect - in that order.

Other than affecting a ton of the usual stuff like carry weight, health, melee damage, and being a requirement for wielding heavier weapons, Strength is also, unexpectedly, the primary source of intimidating responses in conversations. And it’s checked. All. The. Time. Of all characteristics, it’s possible that Strength checks allow for the most number of successful quest resolutions (topping even Personality).

Personality lacks any immediate impact on your character and mostly works as a narrative crutch that gives you access to quests, their peaceful resolutions, and more. It deserves the second place in our Trinity thanks to allowing you to recruit an otherwise unavailable companion. The added firepower is considerable. Ra-ta-ta-ta-ta goes the Soviet tap dance!

Finally, Intellect affects the number of skill points you get on level ups, one of the most important derived statistics. Other than that, it’s checked quite frequently and a tremendous help in quests and exploration.

The skills are much simpler. Most of them help you with one or two things: Weapon skills increase accuracy; Lock Picking allows you to open locks of various complexity; Survival raises the chance to avoid battles on the world map and gives meals more restorative power.

It’s important to note that characteristics are much more helpful for role-playing purposes than skills. Most of the checks in the game world require appropriate values in characteristics. And Speechcraft. Of course, Speechcraft. Other skills are checked fairly infrequently. I don’t think I encountered a single Stealth check in my entire playthrough. First Aid was checked to little effect once or twice. If you’ve got high enough Unarmed combat, some heads can be caved in during dialogue with a single key press. Pretty convenient.

Distinctions are your local traits, but compared to a certain other game, they impact your character quite a bit more. Morphine Doctor gives you +1 Intellect, +10 First Aid, and extra 50% to the chance to get addicted to substances. Cursed Sniper nets you +2 Attention and +7% hit chance to aimed shots in exchange for -2 Luck and -10% chance to hit enemies with regular shots. A lot of them have obvious roles in shaping a character. I haven’t noticed anything as egregious in its universal usefulness as Gifted or Good natured.

When you finally decide that your character is exactly right, you get the chance to select the level of difficulty. It’s a good time to stop and ponder the choice a little. You see, difficulty levels in ATOM RPG have a very important yet undocumented effect to them: they affect the amount of ability points you get on level ups. It’s 3 for Easy, 2 for Normal, and 1 for Expert.

And while the game is not very challenging even on Expert, some players may find it upsetting to receive lesser rewards at level ups (especially since the amount of awarded experience is already tied to difficulty).

Abilities themselves are somewhat simple bonuses like +10 to survival, +20% defense against being knocked down, -1 AP for attacks with pistols and submachine guns, or removing the malus for using shields. Frankly, they’re a bit underwhelming but serviceable enough.

As the convention dictates, you'll be able to take those brass knuckles away from him later. Along with his hands.

Right after the birth of your character, a short introductory vignette leaves them robbed, humiliated, and stranded in the unfamiliar wilderness. It’s a good time to gather some materials from your immediate surroundings and assemble a shiv or zip gun. The crafting system is fairly simple and mostly covers your equipment needs during the early stages of the game. With a little investment in Tinkering, you’ll be able to combine such useful items as glue, mushrooms, and old newspapers to great effect.

Outfitted with powerful artifacts like telnyashka and makeshift knuckledusters, you’re finally ready to leave for Otradnoye, the first step in your arduous journey. And that’s when things start getting really interesting in ATOM RPG.

Intertext

First, let’s address the enormous, almost embarrassingly fat elephant in the room before proceeding. The elephant that, before now, I have tried not to glance at too often.

ATOM RPG is exceedingly postmodernist. Actually, I’m fairly certain that it’s the most conventionally postmodernist game I have ever played. Virtually its every aspect is a citation. Its source may be an old Soviet song, a socialist realist film, an actor from the era of Perestroika, a novel written by a dissident, a controversial public figure, an internet meme (yikes), or Fallout. A lot of Fallout. At its most surface level, mechanically and story-wise, ATOM is made of Fallout. It’s got its own Iguana Bob, Richard Grey, The Followers, Rad-X, Vaults, FEV, the BoS, etc. Whether it’s part of the nostalgia motif, a set of homages, or plagiarism is for you to decide, but I think it fits the game’s fever dream feel very well.

It’s not Fallout 2, however, where the elements of its first part were deconstructed to inspect them from a different perspective, but rather a boxful of stuff to play with. In Atom Team’s hands, the borrowed material is clay to create a statue of Lenin with, tear it down, and then make a million other things following the same scenario. It’s playful, lively, and not preachy in any way.

A fair warning, though: like with any PM text, to enjoy ATOM fully, you’ll probably need to play it in Russian and be quite a prestigious Codexer who is no stranger to the 20th century Russian culture. Half the game’s population talks in direct quotes from literature, songs, films, or Soviet clichés. Knowing Sorokin, Yerofeyev, Zinovyev, and Shalamov is a must. Otherwise, you’ll be doomed to giggle at jokes about bigots assuming someone’s hunger level for the 40 to 50 hours required to finish the game. Which is funny enough, I guess, but the game’s main strength lies within the bounds of its literary exercises.

Otradnoye serves as a tutorial village (or as Shady Sands if we were to speak the elephant language), a place designed to be quite moderate in all aspects so as not to overwhelm a beginner. Its secrets are not too obscure; the mutated wildlife is easily dispatched; the quests are simple and easy to follow. The characters are mostly played straight, too.

It’s interesting to note that there are no generic NPCs. Not in Otradnoye, not anywhere else. Every character has their own name, dialogue, and a portrait. Even guards, farmers, and drunkards.

While the ominous implications of this are quite obvious, mostly, ATOM RPG doesn’t degenerate into filler conversations. I’d say only about 5 to 10 percent of all NPCs don’t have anything notable about them. Usually, even if they haven’t got a role in the grander scheme of things, people either have an interesting rumor to share or reference/parody/quote some other Russian text (thus amusing you a bit, hopefully).

Structurally, the conversations are pretty basic. If a character is not involved in a quest of some kind, you’ll only be able to ask them the same four questions. This highlights one somewhat major problem with the game’s dialogues: it seems that some of them have been done absentmindedly, almost on autopilot. More than once I have found myself scratching my head in surprise at some painfully obvious and stupid sentences. A few dozen conversations read (clearly unintentionally) like an unedited stream of consciousness. Again, it’s for you to decide if that’s a dadaist technique that deepens the artistic merit of ATOM or laziness/lack of time on the part of Atom Team.

But when conversations are good, they are witty, often times hilarious, and even touching. Death or misery is rarely the punch line to a joke. The writers are clearly in love with the strange and eccentric but never do they take sides. Be it a hypocritical cult leader, wacky conspiracy theorist, devoted red commissar, or time traveler who is often confused by his own omniscience, all of them are exaggerated to emphasize the qualities that make them tick.

One of the core qualities of ATOM RPG is the polyphony of its texts. I’ve never met a preachy character whom I’d comfortably call a raisonneur. All those distinct voices form an almost non-hierarchical constellation where every star’s got a fair amount of time to shine (even if it results in their becoming supernovae). Today, when writing in games lacks almost any sort of tasteful framing for its author’s beliefs, it’s very refreshing not to be constantly told about ‘evil’ this and ‘virtuous’ that.

Unfortunately, there are a few party poopers that are consistent across everything that’s written in ATOM RPG. Their names are Typos, Inelegant Syntax, and Wrong Punctuation. It shows that the game still needs a bit of work, but these problems are quite solvable, and with the amount of post-release support Atom Team has been providing so far, I’m sure they’re going to be ironed out eventually.

It’d be unthinkable if such an eclectic cast of characters didn’t include some restless souls to adventure with. From a faithful wolfhound to an undercover ATOM operative to a legendary Soviet writer, our companions form a balanced roster of both mundane and eccentric personalities.

Without a doubt, the most prominent of them is Hexogen, a doppelgänger of the Russian writer Alexander Prokhanov. Hexogen is equally unhinged, energetic, talented, and outspoken as his real-life counterpart. Out of all companions, he probably has the most to say about the player’s actions and decisions. I can only imagine how difficult it was to exaggerate Prokhanov’s character for the purposes of writing Hexogen due to him being as outstanding as he is. On a side note, I’ve been told that Atom Team has tried to write Hexogen’s lines as close to Prokhanov’s writing style as possible; however, I’d say that he talks more like Andrei Platonov instead.

Speaking of writing styles: I don’t think it’s a coincidence that it is Hexogen who has seen so much work and love from the developers. ATOM RPG’s atmosphere evokes the feel of Prokhanov’s books in more than one way. Their dreamy, feverish, unreal qualities have clearly left a lasting impression on the game’s writers. Quite an influence if you ask me.

The only thing that detracts from the experience of fraternizing with your comrades is their awful AI and pathfinding. Be prepared for them to go full Ian on your back and run to the other side of the map when you as much as take a step in the opposite direction. The ability to give orders to them in combat helps somewhat, but their crazy behavior spoils your impression of them as characters a bit.

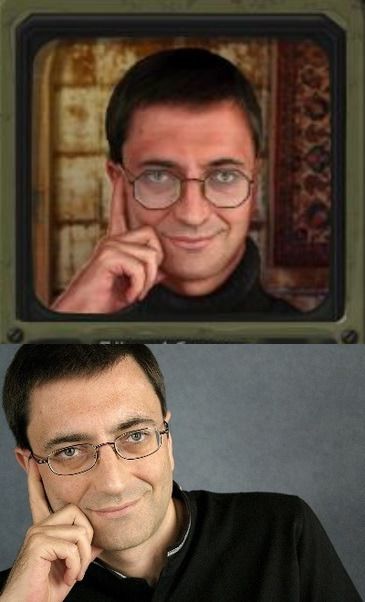

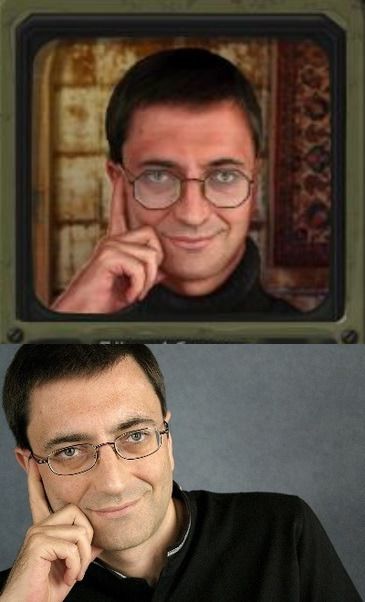

As for portraits, I can imagine it being one of the more polarizing aspects of ATOM RPG. Simply put, almost every portrait in the game uses the photo of a real person as its base. Try not to faint when you see the Russian version of The Three Stooges camping outside a military bunker. The famous rapper Pasha the Technician will see to all your engineering needs. Some bandits look like gangsters from a post-Perestroika TV series. Examples are almost as numerous as the characters in the game. I can only imagine how jarring that is going to be for the uninitiated. The rabbit hole goes exceptionally deep. Take a deep breath, and either relax and have fun or keep your eyes closed. Either way, you’re going to be traumatized - for better or for worse.

Dmitry Volchek, a poet, translator, book publisher. He has made Burroughs, Crowley, Robbe-Grillet, Artaud, and other fringe authors available for Russians. In ATOM RPG, he is one of Peregon’s politicians.

Metatext

As far as I see it, you, my dear reader, have two choices: play ATOM RPG as a Fallout clone or, if you’re feeling adventurous, try to approach it a bit differently.

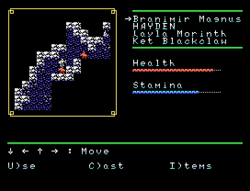

As a clone, it’s pretty solid. It’s got purty graphics, quests with multiple approaches to solving them, gunfights against a variety of human garbage, S.P.E.C.I.A.L. After helping out in Otradnoye, you’ll encounter the usual world map (and two extra empty ones with a couple of locations each; these desperately need more content), its own Necropolis, The Hub, Deathclaws. During your trip down the memory lane, the moody ambient soundtrack will remind you of Mark Morgan a lot. You’ll be able to level up, shoot a variety of rusty Soviet guns, and have generally good RPG fun. There’s nothing to say that you don’t already know. And if for some unthinkable reason you haven’t played Fallout yet, you’ve got bigger fish to fry than playing ATOM. But if you’re a fan, you’ll most likely have a mighty good time exploring this little DIY reimagining of a beloved game.

It’s a bit more ambiguous with the second approach. I’ve tried and, I feel, failed. I just couldn’t find a way to reconcile the game’s literary aspirations with its mechanical, ‘gamey’ parts. So I played it more or less like a book. As a book, ATOM RPG is of the kind that you’d find in the flat of a dead Henry Darger. I guess, our atomic team of dargers liked Fallout and RPGs more than angelic children and dadaist collaging, huh.

As Tim Cain once, allegedly, said, ‘My idea is to explore more of the world and more of the ethics of a post-nuclear world, not to make a better plasma gun.’ Atom Team has made a game that explores what it was like to be a curious kid basking in post-Dissolution Russia’s culture. The real one that is. And like in Fallout, ATOM the Game is, for the most part, a space for ATOM the Text to inhabit. ATOM RPG's exploration of its main theme goes much further, though.

At the end of the day, ATOM RPG is a singular artifact unlike any other. Thanks to their energetic, inquisitive, and truly alive writers, Atom Team has managed to successfully splice the cranks of our real world with the haze of post-apocalyptic nostalgia. If Hexogen, and to some extent Prokhanov, were to make a video game, I’m sure he’d create something that’d feel not unlike ATOM RPG.

It’s my sincerest belief that if we get more games like this one, our grandchildren won’t laugh at us as hard. And thank god for the strange and eccentric.

A song is much more important

than any material possession:

it brings people together.

And that’s the most difficult and valuable of all.

Andrei Platonov. Doubting Makar.

Context

In 1991, the world saw the end of an era. Despite the common anxiety, not a single atomic bomb brought its demise. Outside: a promise of a bright future, free of The Party's weakened stranglehold; inside: poverty, depression, loss of identity and agency. A year later, necrorealism lost its status as an avantgarde art movement. Literature, film, visual art became disproportionately interested in decay, rot, and the undead. The orthodox eschatology seemingly disappeared, and the posthumous fate of the nation resembled that of a senselessly roaming ghoul. It would take another decade for the polite (if still confused) audience to become engorged with blood enough to move on and start looking for a new beginning. However, in some places, the gloom of the 90s persisted. The apocalypse cult had firmly planted its roots. While the emerging middle class was searching for an identity outside the borders of their native ruin, some people refused to assimilate into an increasingly globalized, homogeneous world. In this state of conscious undeath, they still dream of skeletonized brutalist cities stretching to the horizon and into the dead sun.

Atom Team, a Latvia-based game development studio responsible for ATOM RPG, may very well be of this nostalgic tribe, even if only partially. Having successfully raised $33 000 of $15 000 required to realize their dream of making a Soviet-flavored post-apocalyptic game, they released ATOM RPG in early access at the end of 2017. A little over a year later, the game reached its official 1.0 status to the subaudible fanfares of a dedicated yet somewhat small group of fans that the studio had amassed thanks to their overwhelmingly professional, friendly, and attentive interactions with the community. Even though the game is officially finished, Atom Team has promised to continue expanding and adding fresh content to it. This review is written with versions 1.0-1.04 in mind, hence some parts of the game may change.

Text

Unlike the real world, ATOM’s version of the USSR ended with a bang rather than a whimper. In 1986, a date suspiciously close to the beginning of Perestroika, Cold War came to an abrupt and violent halt. A decades-long rivalry finally ended in mutual nuclear annihilation. The divine broom swept most of the traces of humanity from the planet. However, not even atomic bombs could eradicate life entirely. With the exception of some mutated wildlife, the new and emerging world of post-apocalyptic 90s was not unlike its real-life counterpart: roaming gangs, rotting junkies, lawlessness, and a small number of decent people trying to make it through the anarchy.

The game is set in 2003, in the times when the past is all but forgotten, and the future hasn’t been written yet. Despite the apparent dissolution of the USSR, the denizens of this world still cling to their Soviet identity, even if it hurts their immediate interests. Unbeknownst to them, their desperate struggle to retain a modicum of their former self is assisted by a mysterious military organization called ATOM. With apparent parallels to the Brotherhood of Steel, they are a secretive, well-trained and equipped underground group whose goal is to preserve the Soviet legacy and bring the socialist utopia back to the Wasteland - this time without a mortal enemy to hold them back.

The player is given the role of a member of ATOM who is sent on a dangerous mission of locating a missing expedition led by enigmatic general Morozov. As expected, following his trail leads you to discovering the nature of ATOM, circumstances surrounding the nuclear war, great conspiracies, and possibly a new, greater life for the Wasteland. The most profound mystery of ATOM RPG, undoubtedly, is the [REDACTED] conducted in [REDACTED] to [REDACTED] forever. Better fasten your seatbelt!

This premise is familiar to anyone who has played Fallout, and it’s obvious that it’s been purposefully constructed this way to invoke a strong image of it. On the surface level, ATOM RPG’s script is a remix of Fallout’s story, sure, but it’s not a deconstruction. Many plot elements and world details have been lifted from the immortal post-apocalyptic adventure almost verbatim and then shuffled, seemingly randomly. Some major story points of Fallout have been reduced to gags while others retain their importance. Despite this almost damning characteristic, conceptually, it works in favor of both the ‘nostalgia for Fallout’ angle and creating some fitting imagery for ATOM RPG’s own universe. Without spoiling much, I’ll just say that the word ‘Unity’ becomes frighteningly appropriate in this game...

ATOM RPG’s main menu greets us with a very suitable view: an unknown, apparently military man is walking away from the camera and into a ruined city. The sun is setting (rising?) in the background. We hear a nostalgic Soviet song ‘Blue Cities.’ Its lyrics paint a hazy picture where the past and future flow into each other forming the present. After a while, the man has gone, and the song has ended. Oppressive silence now accompanies the still city.

It becomes clear: ATOM is not a cautionary tale but a reminiscence.

For me, this picture was the first sign that indicated that I had been overly naive in thinking that ATOM RPG would be a mere repaint of Fallout. As it turned out later, its nostalgia longs not for Interplay’s game but for something more precious and unobtainable. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Clicking New Game takes you straight to the character creation screen.

[Attention] It reminds me of an iconic game from the old days.

[Success] Indeed, everything here is as you would expect from a Soviet Post-Apocalyptic Role Playing Game.

The most special and defining part of your character is their characteristics. Each of them affects the numeric values of skills and derived statistics such as Sequence, Health, or Action Points.

Unlike The Game, none of the characteristics can be neglected completely, and all of them often get checked in various in-game situations. Even the ones that don’t get as much use as Strength or Personality have some redeeming qualities that make dumping them yield some undesirable results. For example, endurance, for which there aren’t even half a dozen checks, governs the most important statistic of them all: health; even luck not only affects the outcomes of, supposedly, all skill checks you make, but its high values also allow you to safely bypass some of the most difficult fights in the game (in the world of ATOM RPG, crossing your fingers may prove more deadly for your opposition than a carpet bombing).

However, there are characteristics that are much more useful than the others. The Holy Trinity is Strength, Personality, Intellect - in that order.

Other than affecting a ton of the usual stuff like carry weight, health, melee damage, and being a requirement for wielding heavier weapons, Strength is also, unexpectedly, the primary source of intimidating responses in conversations. And it’s checked. All. The. Time. Of all characteristics, it’s possible that Strength checks allow for the most number of successful quest resolutions (topping even Personality).

Personality lacks any immediate impact on your character and mostly works as a narrative crutch that gives you access to quests, their peaceful resolutions, and more. It deserves the second place in our Trinity thanks to allowing you to recruit an otherwise unavailable companion. The added firepower is considerable. Ra-ta-ta-ta-ta goes the Soviet tap dance!

Finally, Intellect affects the number of skill points you get on level ups, one of the most important derived statistics. Other than that, it’s checked quite frequently and a tremendous help in quests and exploration.

The skills are much simpler. Most of them help you with one or two things: Weapon skills increase accuracy; Lock Picking allows you to open locks of various complexity; Survival raises the chance to avoid battles on the world map and gives meals more restorative power.

It’s important to note that characteristics are much more helpful for role-playing purposes than skills. Most of the checks in the game world require appropriate values in characteristics. And Speechcraft. Of course, Speechcraft. Other skills are checked fairly infrequently. I don’t think I encountered a single Stealth check in my entire playthrough. First Aid was checked to little effect once or twice. If you’ve got high enough Unarmed combat, some heads can be caved in during dialogue with a single key press. Pretty convenient.

Distinctions are your local traits, but compared to a certain other game, they impact your character quite a bit more. Morphine Doctor gives you +1 Intellect, +10 First Aid, and extra 50% to the chance to get addicted to substances. Cursed Sniper nets you +2 Attention and +7% hit chance to aimed shots in exchange for -2 Luck and -10% chance to hit enemies with regular shots. A lot of them have obvious roles in shaping a character. I haven’t noticed anything as egregious in its universal usefulness as Gifted or Good natured.

When you finally decide that your character is exactly right, you get the chance to select the level of difficulty. It’s a good time to stop and ponder the choice a little. You see, difficulty levels in ATOM RPG have a very important yet undocumented effect to them: they affect the amount of ability points you get on level ups. It’s 3 for Easy, 2 for Normal, and 1 for Expert.

And while the game is not very challenging even on Expert, some players may find it upsetting to receive lesser rewards at level ups (especially since the amount of awarded experience is already tied to difficulty).

Abilities themselves are somewhat simple bonuses like +10 to survival, +20% defense against being knocked down, -1 AP for attacks with pistols and submachine guns, or removing the malus for using shields. Frankly, they’re a bit underwhelming but serviceable enough.

As the convention dictates, you'll be able to take those brass knuckles away from him later. Along with his hands.

Right after the birth of your character, a short introductory vignette leaves them robbed, humiliated, and stranded in the unfamiliar wilderness. It’s a good time to gather some materials from your immediate surroundings and assemble a shiv or zip gun. The crafting system is fairly simple and mostly covers your equipment needs during the early stages of the game. With a little investment in Tinkering, you’ll be able to combine such useful items as glue, mushrooms, and old newspapers to great effect.

Outfitted with powerful artifacts like telnyashka and makeshift knuckledusters, you’re finally ready to leave for Otradnoye, the first step in your arduous journey. And that’s when things start getting really interesting in ATOM RPG.

Intertext

First, let’s address the enormous, almost embarrassingly fat elephant in the room before proceeding. The elephant that, before now, I have tried not to glance at too often.

ATOM RPG is exceedingly postmodernist. Actually, I’m fairly certain that it’s the most conventionally postmodernist game I have ever played. Virtually its every aspect is a citation. Its source may be an old Soviet song, a socialist realist film, an actor from the era of Perestroika, a novel written by a dissident, a controversial public figure, an internet meme (yikes), or Fallout. A lot of Fallout. At its most surface level, mechanically and story-wise, ATOM is made of Fallout. It’s got its own Iguana Bob, Richard Grey, The Followers, Rad-X, Vaults, FEV, the BoS, etc. Whether it’s part of the nostalgia motif, a set of homages, or plagiarism is for you to decide, but I think it fits the game’s fever dream feel very well.

It’s not Fallout 2, however, where the elements of its first part were deconstructed to inspect them from a different perspective, but rather a boxful of stuff to play with. In Atom Team’s hands, the borrowed material is clay to create a statue of Lenin with, tear it down, and then make a million other things following the same scenario. It’s playful, lively, and not preachy in any way.

A fair warning, though: like with any PM text, to enjoy ATOM fully, you’ll probably need to play it in Russian and be quite a prestigious Codexer who is no stranger to the 20th century Russian culture. Half the game’s population talks in direct quotes from literature, songs, films, or Soviet clichés. Knowing Sorokin, Yerofeyev, Zinovyev, and Shalamov is a must. Otherwise, you’ll be doomed to giggle at jokes about bigots assuming someone’s hunger level for the 40 to 50 hours required to finish the game. Which is funny enough, I guess, but the game’s main strength lies within the bounds of its literary exercises.

Otradnoye serves as a tutorial village (or as Shady Sands if we were to speak the elephant language), a place designed to be quite moderate in all aspects so as not to overwhelm a beginner. Its secrets are not too obscure; the mutated wildlife is easily dispatched; the quests are simple and easy to follow. The characters are mostly played straight, too.

It’s interesting to note that there are no generic NPCs. Not in Otradnoye, not anywhere else. Every character has their own name, dialogue, and a portrait. Even guards, farmers, and drunkards.

While the ominous implications of this are quite obvious, mostly, ATOM RPG doesn’t degenerate into filler conversations. I’d say only about 5 to 10 percent of all NPCs don’t have anything notable about them. Usually, even if they haven’t got a role in the grander scheme of things, people either have an interesting rumor to share or reference/parody/quote some other Russian text (thus amusing you a bit, hopefully).

Structurally, the conversations are pretty basic. If a character is not involved in a quest of some kind, you’ll only be able to ask them the same four questions. This highlights one somewhat major problem with the game’s dialogues: it seems that some of them have been done absentmindedly, almost on autopilot. More than once I have found myself scratching my head in surprise at some painfully obvious and stupid sentences. A few dozen conversations read (clearly unintentionally) like an unedited stream of consciousness. Again, it’s for you to decide if that’s a dadaist technique that deepens the artistic merit of ATOM or laziness/lack of time on the part of Atom Team.

But when conversations are good, they are witty, often times hilarious, and even touching. Death or misery is rarely the punch line to a joke. The writers are clearly in love with the strange and eccentric but never do they take sides. Be it a hypocritical cult leader, wacky conspiracy theorist, devoted red commissar, or time traveler who is often confused by his own omniscience, all of them are exaggerated to emphasize the qualities that make them tick.

One of the core qualities of ATOM RPG is the polyphony of its texts. I’ve never met a preachy character whom I’d comfortably call a raisonneur. All those distinct voices form an almost non-hierarchical constellation where every star’s got a fair amount of time to shine (even if it results in their becoming supernovae). Today, when writing in games lacks almost any sort of tasteful framing for its author’s beliefs, it’s very refreshing not to be constantly told about ‘evil’ this and ‘virtuous’ that.

Unfortunately, there are a few party poopers that are consistent across everything that’s written in ATOM RPG. Their names are Typos, Inelegant Syntax, and Wrong Punctuation. It shows that the game still needs a bit of work, but these problems are quite solvable, and with the amount of post-release support Atom Team has been providing so far, I’m sure they’re going to be ironed out eventually.

It’d be unthinkable if such an eclectic cast of characters didn’t include some restless souls to adventure with. From a faithful wolfhound to an undercover ATOM operative to a legendary Soviet writer, our companions form a balanced roster of both mundane and eccentric personalities.

Without a doubt, the most prominent of them is Hexogen, a doppelgänger of the Russian writer Alexander Prokhanov. Hexogen is equally unhinged, energetic, talented, and outspoken as his real-life counterpart. Out of all companions, he probably has the most to say about the player’s actions and decisions. I can only imagine how difficult it was to exaggerate Prokhanov’s character for the purposes of writing Hexogen due to him being as outstanding as he is. On a side note, I’ve been told that Atom Team has tried to write Hexogen’s lines as close to Prokhanov’s writing style as possible; however, I’d say that he talks more like Andrei Platonov instead.

Speaking of writing styles: I don’t think it’s a coincidence that it is Hexogen who has seen so much work and love from the developers. ATOM RPG’s atmosphere evokes the feel of Prokhanov’s books in more than one way. Their dreamy, feverish, unreal qualities have clearly left a lasting impression on the game’s writers. Quite an influence if you ask me.

The only thing that detracts from the experience of fraternizing with your comrades is their awful AI and pathfinding. Be prepared for them to go full Ian on your back and run to the other side of the map when you as much as take a step in the opposite direction. The ability to give orders to them in combat helps somewhat, but their crazy behavior spoils your impression of them as characters a bit.

As for portraits, I can imagine it being one of the more polarizing aspects of ATOM RPG. Simply put, almost every portrait in the game uses the photo of a real person as its base. Try not to faint when you see the Russian version of The Three Stooges camping outside a military bunker. The famous rapper Pasha the Technician will see to all your engineering needs. Some bandits look like gangsters from a post-Perestroika TV series. Examples are almost as numerous as the characters in the game. I can only imagine how jarring that is going to be for the uninitiated. The rabbit hole goes exceptionally deep. Take a deep breath, and either relax and have fun or keep your eyes closed. Either way, you’re going to be traumatized - for better or for worse.

Dmitry Volchek, a poet, translator, book publisher. He has made Burroughs, Crowley, Robbe-Grillet, Artaud, and other fringe authors available for Russians. In ATOM RPG, he is one of Peregon’s politicians.

Metatext

As far as I see it, you, my dear reader, have two choices: play ATOM RPG as a Fallout clone or, if you’re feeling adventurous, try to approach it a bit differently.

As a clone, it’s pretty solid. It’s got purty graphics, quests with multiple approaches to solving them, gunfights against a variety of human garbage, S.P.E.C.I.A.L. After helping out in Otradnoye, you’ll encounter the usual world map (and two extra empty ones with a couple of locations each; these desperately need more content), its own Necropolis, The Hub, Deathclaws. During your trip down the memory lane, the moody ambient soundtrack will remind you of Mark Morgan a lot. You’ll be able to level up, shoot a variety of rusty Soviet guns, and have generally good RPG fun. There’s nothing to say that you don’t already know. And if for some unthinkable reason you haven’t played Fallout yet, you’ve got bigger fish to fry than playing ATOM. But if you’re a fan, you’ll most likely have a mighty good time exploring this little DIY reimagining of a beloved game.

It’s a bit more ambiguous with the second approach. I’ve tried and, I feel, failed. I just couldn’t find a way to reconcile the game’s literary aspirations with its mechanical, ‘gamey’ parts. So I played it more or less like a book. As a book, ATOM RPG is of the kind that you’d find in the flat of a dead Henry Darger. I guess, our atomic team of dargers liked Fallout and RPGs more than angelic children and dadaist collaging, huh.

As Tim Cain once, allegedly, said, ‘My idea is to explore more of the world and more of the ethics of a post-nuclear world, not to make a better plasma gun.’ Atom Team has made a game that explores what it was like to be a curious kid basking in post-Dissolution Russia’s culture. The real one that is. And like in Fallout, ATOM the Game is, for the most part, a space for ATOM the Text to inhabit. ATOM RPG's exploration of its main theme goes much further, though.

At the end of the day, ATOM RPG is a singular artifact unlike any other. Thanks to their energetic, inquisitive, and truly alive writers, Atom Team has managed to successfully splice the cranks of our real world with the haze of post-apocalyptic nostalgia. If Hexogen, and to some extent Prokhanov, were to make a video game, I’m sure he’d create something that’d feel not unlike ATOM RPG.

It’s my sincerest belief that if we get more games like this one, our grandchildren won’t laugh at us as hard. And thank god for the strange and eccentric.