RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Richard Seaborne on Escape from Hell, Myraglen, and Prophecy

RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Richard Seaborne on Escape from Hell, Myraglen, and Prophecy

Codex Interview - posted by Crooked Bee on Mon 26 January 2015, 19:40:04

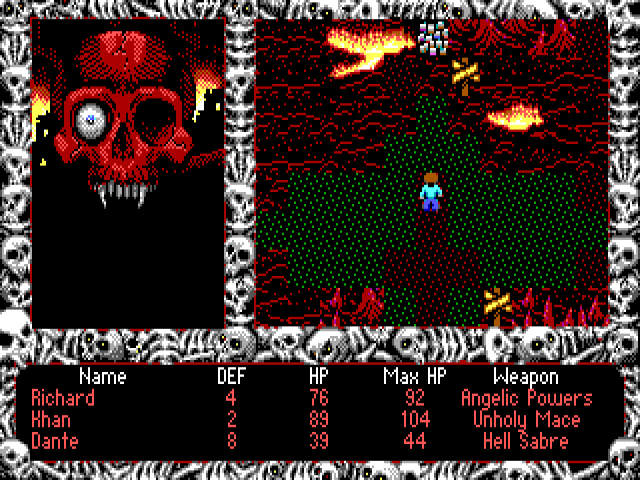

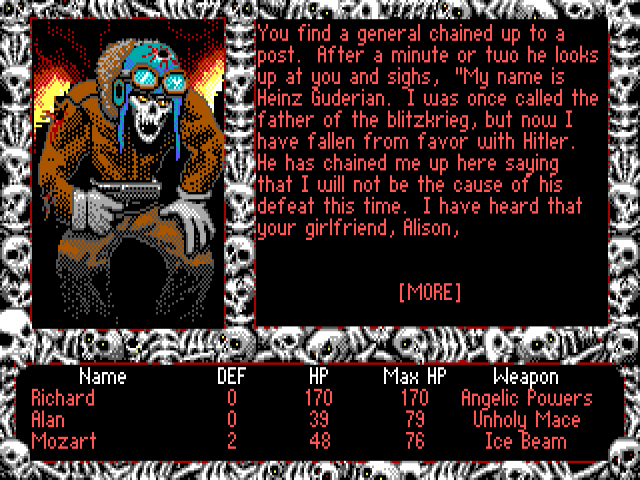

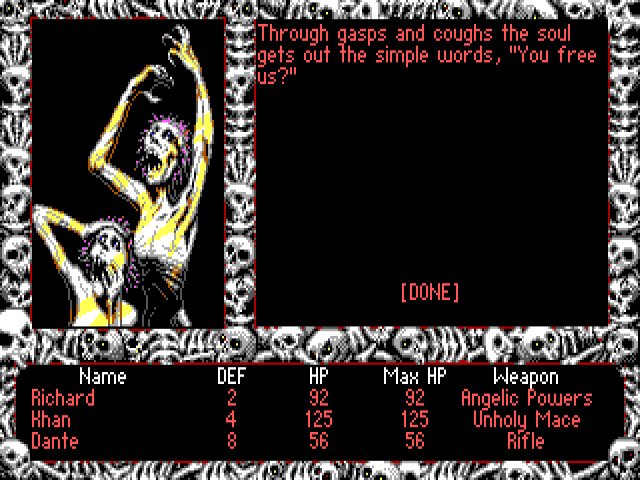

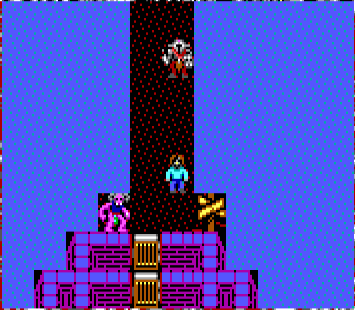

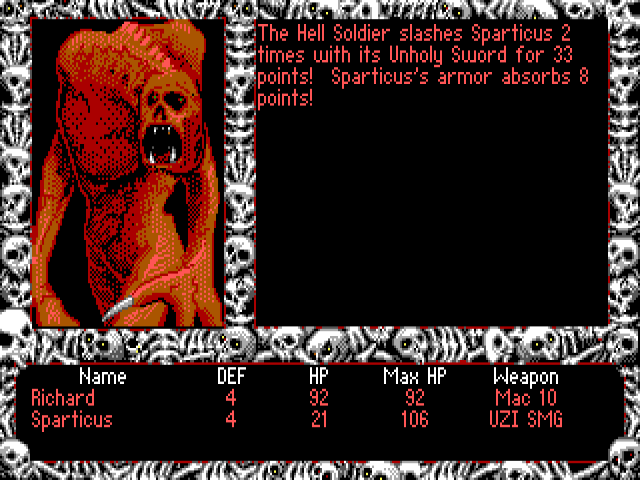

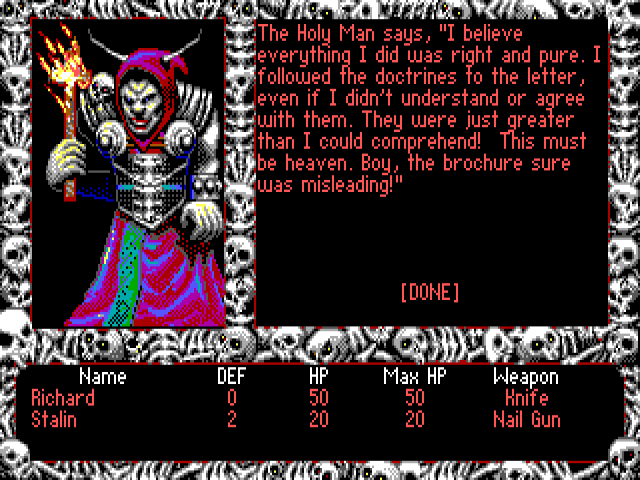

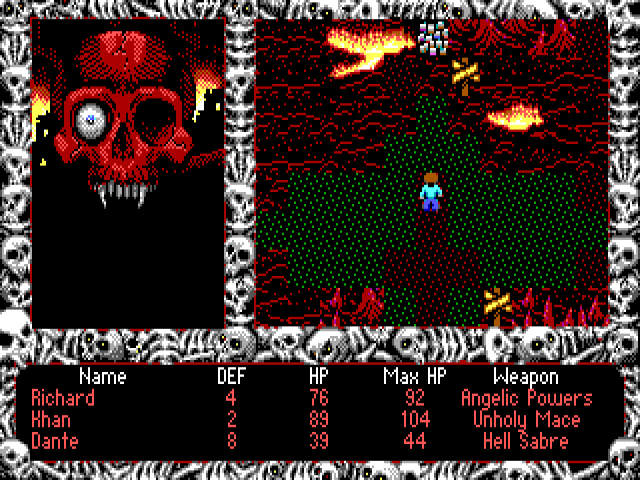

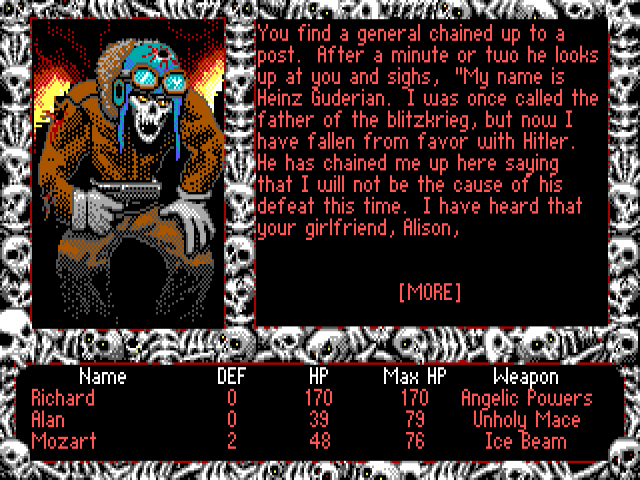

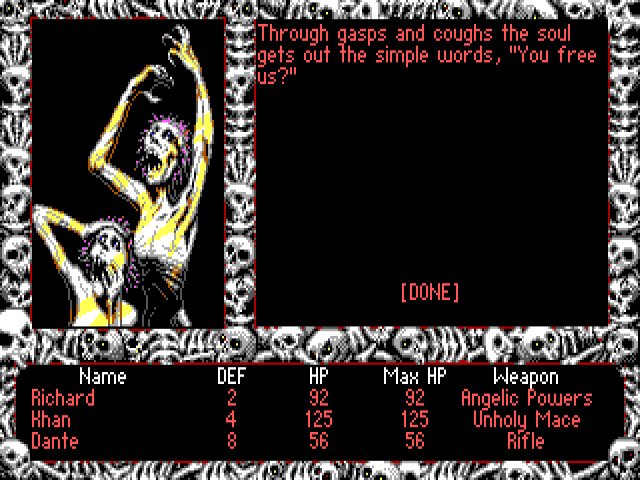

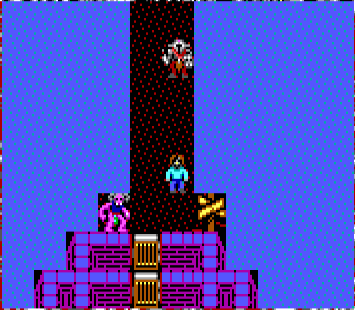

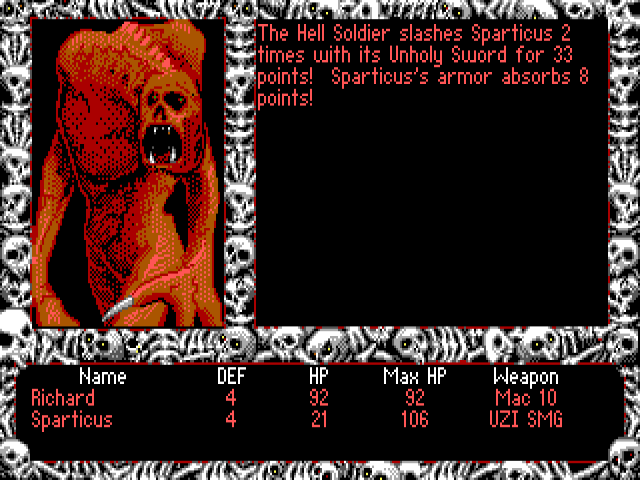

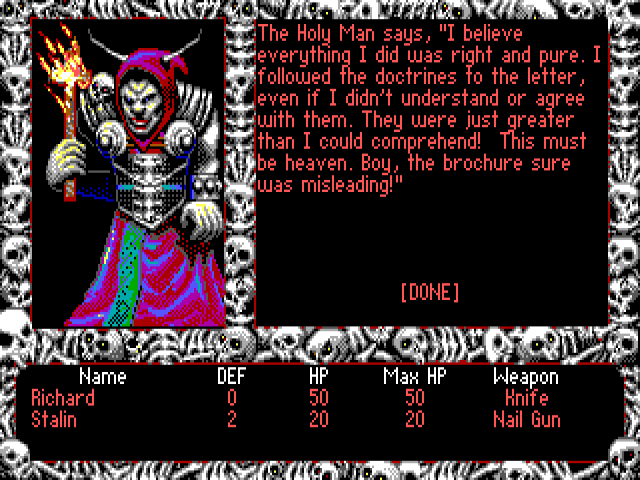

Tags: Activision; Electronic Arts; Escape from Hell; Prophecy: The Fall of Trinadon; Retrospective Interview; Richard Seaborne; Tower of MyraglenThis month, January 2015, marks the 25th anniversary of one of the most unique titles in CRPG history, Electronic Arts' 1990 Escape from Hell, designed by Richard L. Seaborne. Imagine something like Wasteland -- a party-, skill-based top-down RPG -- that has you band together with famous historical and literary figures, from Genghis Khan to Hamlet, and explore, literally, the circles of Hell. Along the way, you fight the likes of Al Capone and Satan, learn new skills from Thucydides and Wyatt Earp, among many others, and solve your own and the denizens' problems, which Hell has in spades, with one overarching goal: escaping back to the real world.

As far as CRPG settings go, there has hardly been a more unorthodox one. And the character portraits were fantastic, too.

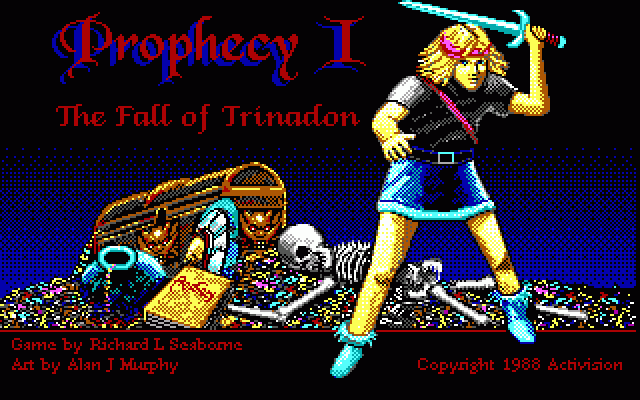

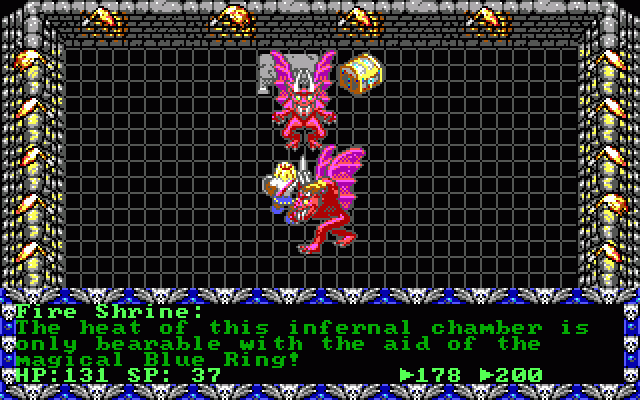

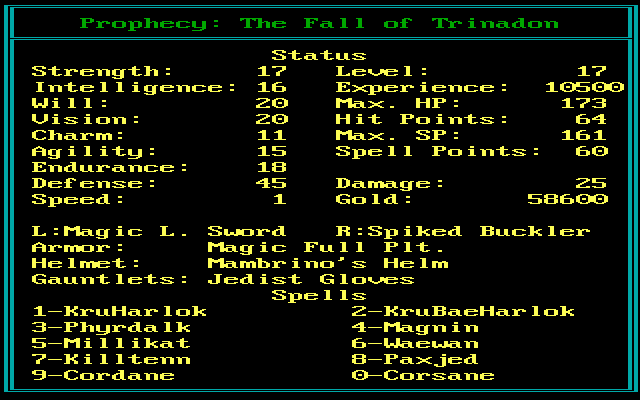

To celebrate the game's anniversary, we've interviewed Richard Seaborne, who currently works at Microsoft, about Escape from Hell along with two other RPGs he worked on, Tower of Myraglen (1987) for the Apple ][GS and Prophecy: The Fall of Trinadon (1989) for the PC. Here's an excerpt:

Read the full interview for many more details about Richard's games, as well as things like team sizes, D&D modules, nudity warning labels, IBM PC vs Apple ][GS, and Trip Hawkins' and other senior EA people's involvement with Escape.

As far as CRPG settings go, there has hardly been a more unorthodox one. And the character portraits were fantastic, too.

To celebrate the game's anniversary, we've interviewed Richard Seaborne, who currently works at Microsoft, about Escape from Hell along with two other RPGs he worked on, Tower of Myraglen (1987) for the Apple ][GS and Prophecy: The Fall of Trinadon (1989) for the PC. Here's an excerpt:

Prophecy’s spell system was especially interesting. You could memorize up to 10 spells, and also increase their effects, etc. (including making the area of effect larger), by adding the proper prefix to the spell name. What made you go for a system like that?

Prophecy’s spell system was fun to make. I think people really enjoy controlling things where their decisions and actions materially change things in the games they play. And they delight in seeing their creations come to life or even blow up in surprising failure. The magic is that their actions had consequence, and they can get better. I wanted the player to feel like an alchemist that could craft their own magic spells according to consistent rules for any situation, seeing magic as a science they could control once learned.

I imagined players would really like having the ability to “program” their own spells through a spell language that included a prefix power amplifier, effect inverter, and foundational spell function. Spells included implicit properties (fire, ice, poison, harm, heal, etc.) and targeting (individual, missile, area of effect/AOE, etc.). A heal spell could be reversed with an inverter to make the spell harm, and a harm spell could be reversed to heal. Spells had a sense of physics too, so if you cast an AOE spell in too small of a space the blast would ricochet off walls and keep expanding through corridors until its “volume” filled its effect area. Adding the most powerful modifiers to an AOE spell could fill most of the screen with a powerful blast, which might be bad for the player if they were in the path of destruction.

How did Electronic Arts end up publishing Escape from Hell? Were they involved in the process of development, and did they influence the final product in any way?

I had always admired Electronic Arts (EA) for their game quality and innovation, and so pitched the concept of Escape from Hell to them not long after Prophecy had shipped. I learned quite a bit about formal planning and ideation while working with EA. I spent nearly six months of the total 12-month development cycle in pre-production, developing engine technology and tools that would ultimately be the foundation of the game and refining the concept with some of EA’s leaders including Trip Hawkins, Bing Gordon, and Dave Albert. It was during this process that Escape changed from a serious traditional RPG to the contemporary grim comedy RPG.

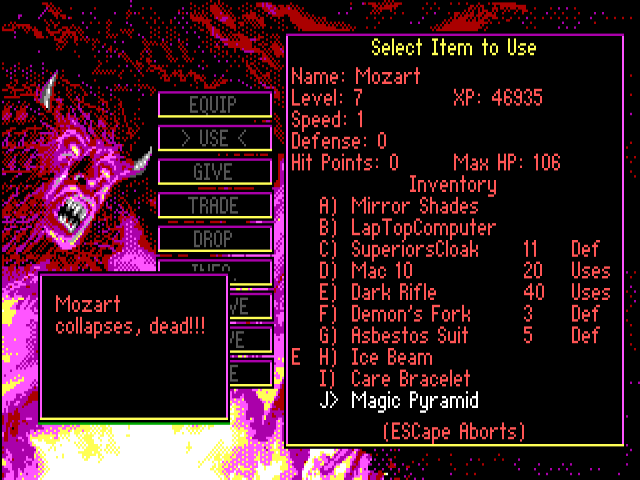

Perhaps the biggest influence that EA had on Escape from Hell was the business pragmatism of Cost of Goods (COGs) and Return on Investment (ROI). They made the decision to reduce the number of discs the game shipped on in half because retailers demanded the game be available on both 5¼” and 3½” discs. It was an unfortunate time in the industry where many computers had just one disc drive size, and so EA had to ship on both disc sizes. To keep costs down, they required Escape to get a lot smaller so the same COGs would cover both disc types.

You can imagine how that went down in terms of the game’s vision and scope – a lot less character and monster art, 9 circles of Hell collapsed to 3 planes of Hell, time & dimensional shift opportunity reduction, and a lot of loose end tying up with these changes. EA offered a Technical Director to help with compression algorithms to fit as much as possible on the discs and a professional writer to brainstorm and help the narrative be as cohesive as possible within the revised scope.

Escape from Hell was released in January 1990, so that January 2015 marks its 25th anniversary. I'm very interested in the way you feel about the game now. Let me put it this way: what is your first thought whenever the game's name comes up? Retrospectively, are you fully satisfied with what kind of game Escape from Hell turned out to be?

Disappointed. Disheartened. Proud. It’s a bit mixed as you can tell.

Escape shipped and had its place in history. I firmly believe it would have been better if it hadn’t had its media budget cut in half, forcing it to miss out on all Nine Circles of Hell, signature art for key characters, more demons, monsters, & gear, and more map & script variances according to player actions, party members, and Trident time control. On the other hand, I am proud to have contributed to the early era of CRPG’s, influencing a lot of features, design tenants, and concepts in many games over these twenty-five years.

Prophecy’s spell system was fun to make. I think people really enjoy controlling things where their decisions and actions materially change things in the games they play. And they delight in seeing their creations come to life or even blow up in surprising failure. The magic is that their actions had consequence, and they can get better. I wanted the player to feel like an alchemist that could craft their own magic spells according to consistent rules for any situation, seeing magic as a science they could control once learned.

I imagined players would really like having the ability to “program” their own spells through a spell language that included a prefix power amplifier, effect inverter, and foundational spell function. Spells included implicit properties (fire, ice, poison, harm, heal, etc.) and targeting (individual, missile, area of effect/AOE, etc.). A heal spell could be reversed with an inverter to make the spell harm, and a harm spell could be reversed to heal. Spells had a sense of physics too, so if you cast an AOE spell in too small of a space the blast would ricochet off walls and keep expanding through corridors until its “volume” filled its effect area. Adding the most powerful modifiers to an AOE spell could fill most of the screen with a powerful blast, which might be bad for the player if they were in the path of destruction.

How did Electronic Arts end up publishing Escape from Hell? Were they involved in the process of development, and did they influence the final product in any way?

I had always admired Electronic Arts (EA) for their game quality and innovation, and so pitched the concept of Escape from Hell to them not long after Prophecy had shipped. I learned quite a bit about formal planning and ideation while working with EA. I spent nearly six months of the total 12-month development cycle in pre-production, developing engine technology and tools that would ultimately be the foundation of the game and refining the concept with some of EA’s leaders including Trip Hawkins, Bing Gordon, and Dave Albert. It was during this process that Escape changed from a serious traditional RPG to the contemporary grim comedy RPG.

Perhaps the biggest influence that EA had on Escape from Hell was the business pragmatism of Cost of Goods (COGs) and Return on Investment (ROI). They made the decision to reduce the number of discs the game shipped on in half because retailers demanded the game be available on both 5¼” and 3½” discs. It was an unfortunate time in the industry where many computers had just one disc drive size, and so EA had to ship on both disc sizes. To keep costs down, they required Escape to get a lot smaller so the same COGs would cover both disc types.

You can imagine how that went down in terms of the game’s vision and scope – a lot less character and monster art, 9 circles of Hell collapsed to 3 planes of Hell, time & dimensional shift opportunity reduction, and a lot of loose end tying up with these changes. EA offered a Technical Director to help with compression algorithms to fit as much as possible on the discs and a professional writer to brainstorm and help the narrative be as cohesive as possible within the revised scope.

Escape from Hell was released in January 1990, so that January 2015 marks its 25th anniversary. I'm very interested in the way you feel about the game now. Let me put it this way: what is your first thought whenever the game's name comes up? Retrospectively, are you fully satisfied with what kind of game Escape from Hell turned out to be?

Disappointed. Disheartened. Proud. It’s a bit mixed as you can tell.

Escape shipped and had its place in history. I firmly believe it would have been better if it hadn’t had its media budget cut in half, forcing it to miss out on all Nine Circles of Hell, signature art for key characters, more demons, monsters, & gear, and more map & script variances according to player actions, party members, and Trident time control. On the other hand, I am proud to have contributed to the early era of CRPG’s, influencing a lot of features, design tenants, and concepts in many games over these twenty-five years.

Read the full interview for many more details about Richard's games, as well as things like team sizes, D&D modules, nudity warning labels, IBM PC vs Apple ][GS, and Trip Hawkins' and other senior EA people's involvement with Escape.

This month, January 2015, marks the 25th anniversary of one of the most unique titles in CRPG history, Electronic Arts' 1990 Escape from Hell, designed by Richard L. Seaborne.

Imagine something like Wasteland -- a party-, skill-based top-down RPG -- that has you band together with famous historical and literary figures, from Genghis Khan to Hamlet, and explore, literally, the circles of Hell. Along the way, you fight the likes of Al Capone and Satan, learn new skills from Thucydides and Wyatt Earp, among many others, and solve your own and the denizens' problems, which Hell has in spades, with one overarching goal: escaping back to the real world.

As far as CRPG settings go, there has hardly been a more unorthodox one. Perhaps the only one directly comparable could've been Brian Fargo's Meantime, a canceled time travel RPG from the early 1990s (and, intriguingly, recently trademarked by Fargo again).

Unfortunately, Escape from Hell's original epic scope was cut down by the all too common constraints -- time, money, disk sizes, the usual -- and so only three of the originally planned nine circles made it in, and the multiple endings, innovative in their concept and variety, had to go, too. What remains, however, is still one of the most imaginative games from a highly creative CRPG era. I urge you to give it a try or, barring that, read my Let's Play.

To celebrate the game's anniversary, we've interviewed Richard Seaborne, who currently works at Microsoft, about Escape from Hell along with two other RPGs he worked on, Tower of Myraglen (1987) for the Apple ][GS and Prophecy: The Fall of Trinadon (1989) for the PC, the former a dungeon crawler with an overarching moral theme, nasty traps and ornate writing, and the latter a fairly large action RPG with a unique prefix-based spell system.

In the interview, Richard also talks about how he got into video game development, and the industry today compared to back then.

RPG Codex: To begin this interview, could you tell us a bit about how you got into video games, and computer role-playing games in particular? Did you come from pen and paper RPGs?

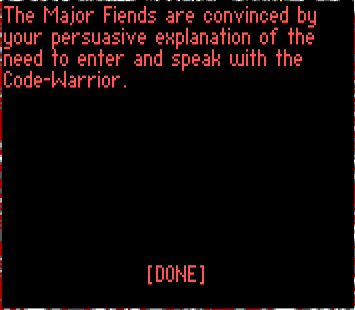

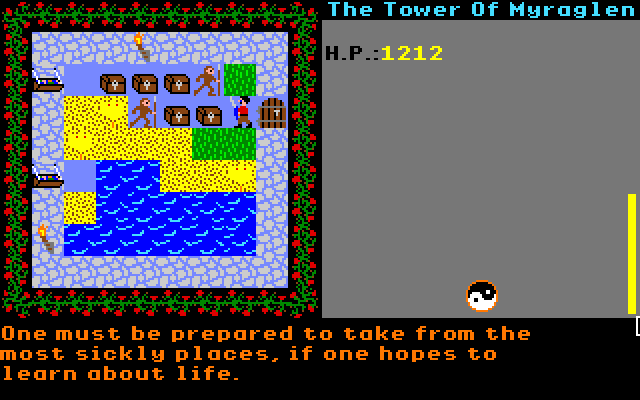

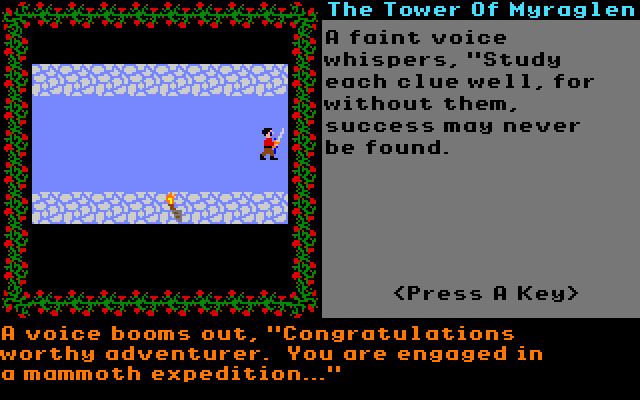

If I'm not mistaken, your first RPG was Tower of Myraglen (1987) for the Apple ][GS. It was a top-down action RPG taking place in a single dungeon and featuring some very ornate writing. How did the idea for the game’s concept and style originate?

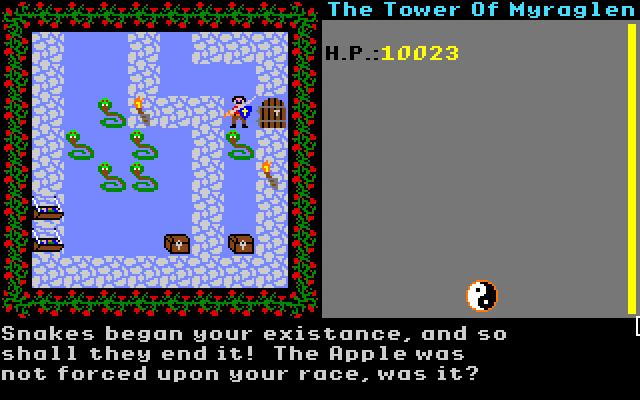

After Tower of Myraglen, you designed Prophecy: The Fall of Trinadon for the PC, published by Activision in 1989. It featured similar action-RPG gameplay to Tower of Myraglen, but with improved graphics, more complex character and inventory systems, and a large scope. Could you talk a bit about what your goals were with Prophecy? In particular, the graphics were really good for a 1989 DOS game – did a lot of effort go into that?

Prophecy’s spell system was especially interesting. You could memorize up to 10 spells, and also increase their effects, etc. (including making the area of effect larger), by adding the proper prefix to the spell name. What made you go for a system like that?

The title screen for Prophecy says "Prophecy I: The Fall of Trinadon," which, I assume, means it was supposed to be the first game in a series. What were your plans for the sequel(s), and why did those plans not come to fruition?

Your next (and, as far as I know, last) RPG was Escape from Hell (1990). It has a very unorthodox setting: it is a role-playing game set - literally - in Hell, and it also lets you recruit famous historical individuals to your party. Was there any particular inspiration for the game's concept? Or did you simply grow tired of fantasy clichés typical to the genre?

Your list of inspirations for Escape From Hell is really interesting. You mentioned Dante’s Inferno, among other things, and there is also Shakespeare and his creations, various popular fictive characters, ancient philosophers, all gathered in the underworld. Did you research the subject for the occasion or did you already have an interest in it prior to making the game? Was it a natural thing to include that sort of content in video games 25 years ago or was Escape from Hell more of an exception even back then? Games like Wasteland did include all sorts of popular culture references, but not the comparable amount of historical and literary references, which certainly makes Escape from Hell stand out.

How did Electronic Arts end up publishing Escape from Hell? Were they involved in the process of development, and did they influence the final product in any way?

The text on Escape from Hell’s box went, "WARNING: Contains nudity, violence and controversial images." How did the label come about, and were you happy with it? Do you think it influenced the game's reception?

Just like Fountain of Dreams (also published by EA in 1990), Escape from Hell’s presentation (from the overworld exploration and skill use to animated enemy portraits) looks very similar to another EA game, Wasteland (1988). A lot of websites simply assume Fountain and Escape used the Wasteland engine, but when I asked Brian Fargo about it recently, he told me that probably wasn’t the case since, in his words, “the Wasteland engine could barely be called an engine with all the hand coding you had to do.” He did not, however, completely exclude the possibility that some of the Wasteland code might have been used (even if he considered that improbable, too). Can you shed some light on that? Did you build Escape from Hell's engine from the ground-up, and do you know how much of the code was inherited from Wasteland?

Escape from Hell has a number of fairly unique features. One of those is using special tridents, scattered across Hell, to shape the environment by altering the surrounding landscape and time frame. The idea of shaping the gameworld to your advantage or disadvantage remains, I believe, fairly underexplored even today. Was this feature implemented as fully as you had initially envisaged it?

The game has an "anything goes" tone, but there also seems to be a certain logic behind it. The first few locations do a good job of showing Hell as an organized place, going the "Hell is a bureaucracy"/"bureaucracies are hell" route. The Hell Guard camp and Limbo go a long way of communicating that even in Hell, there are rules. Then Lucifer's Landing just gets blown up on a whim. After that, the illusion of an all-pervasive order is further ruined as we are introduced to the local struggle for power and revenge between Al Capone and Caesar, as well as to Hitler's plans for a coup. Am I overthinking this? I guess I'm just curious to know if there was a plan behind all this hellish madness.

The game is also subversive in that it makes use of some well-known mass murderers. There’s Al Capone, still a boss of the underworld albeit a different kind, and then there are Stalin and Hitler. I find these two interesting because most retrospectives about EFH tend to insist a great deal on the presence of Hitler—found in Dachau no less!—and get seemingly offended by the fact that he can be recruited as a party member, yet very little attention is paid to Stalin, available for recruitment at the start of the game. And Hitler would again appear in a video game two years later in Id Software’s Wolfenstein 3D, this time in the much more acceptable role of the final boss of the original game. Did you expect some controversy to spring up from the use of Stalin and Hitler? Was there even any reaction to that at the game’s release? Is there any reason that pushed you to sort some of these characters as villains (Al Capone) and others as allies (Hitler, Stalin)?

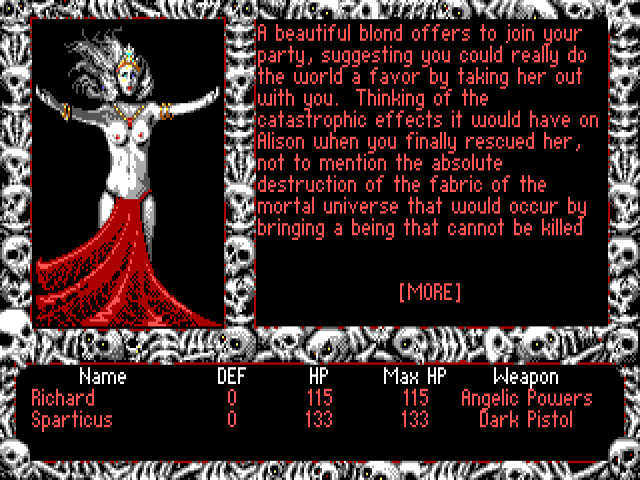

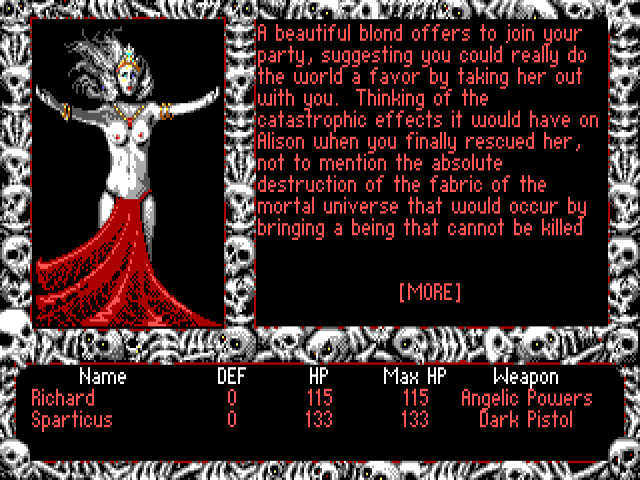

Escape from Hell sometimes hints at alternative endings that don’t seem to have been implemented. The message you get when recruiting Blonde suggests the possibility of rescuing her from Hell instead of Alison, "the catastrophic effects it would have on Alison," and "the absolute destruction of the fabric of the mortal universe that would occur by bringing a being that cannot be killed into it." Similarly, warning you against teaming up with Hitler, Charon implies that Satan may "irrevocably obliterate every last of them, maybe even the entire circle of Hell" if you bring Hitler to the Devil's Fortress. Were any of these endings even planned?

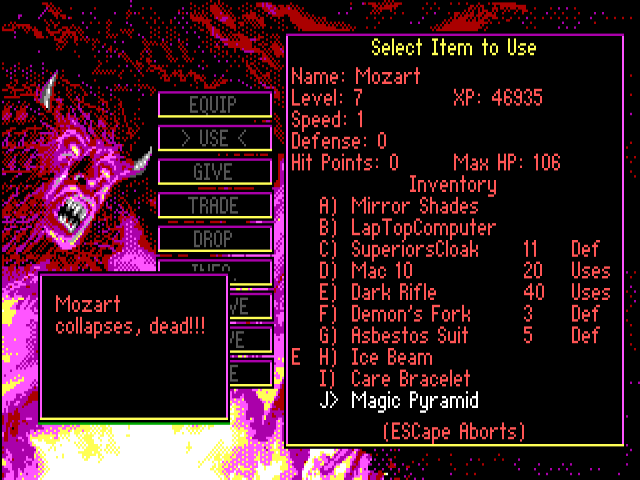

Speaking of endings, an obvious bad ending could have involved being evil enough for the gates of Hell not to let you out. Messing around with the game's files in a hex editor, I came across a hidden attribute that would fit that kind of ending, called “Alignment.” What is the story behind it?

In general, there are some locations and subplots in Escape from Hell that I thought felt somewhat unfinished. How many of the features, quests, skills, items, etc., did you have to scrap? Could you name some of the more interesting content that you could not or did not have time to implement?

Escape from Hell was released in January 1990, so that January 2015 marks its 25th anniversary. I'm very interested in the way you feel about the game now. Let me put it this way: what is your first thought whenever the game's name comes up? Retrospectively, are you fully satisfied with what kind of game Escape from Hell turned out to be?

You said you were refining the game's concept with EA’s senior people like Trip Hawkins (the founder and CEO), Bing Gordon (who, from what I've gathered, was EA's head of marketing and also an occasional project manager at the time), and Dave Albert (the producer). I'd be curious to hear how those meetings went, how frequent they were, and what kinds of things those people would push for. In general, what was the dynamics of the creator - producer - marketing department - CEO relationship back in those days?

You developed games for Apple ][GS (Tower of Myraglen, Sea Strike, Monte Carlo) and then for DOS (Prophecy, Escape from Hell). What was your experience moving from one platform to the other?

For Tower of Myraglen and Prophecy, you collaborated with two graphical designers, Jeff Lefferts and Alan Murphy respectively. Alan worked with you on Escape from Hell, too, whose full title even reads “Richard & Alan’s Escape from Hell.” Could you tell us a bit about Jeff and Alan, and how you got to work with them?

How did you end up going from coding and designing games – from creating your own games, basically – to, it would seem, focusing more on the technical and managerial aspects in the 1990s and 2000s, as Technical Director, Project Manager, and Studio Manager with EA and Microsoft? What does your current work at Microsoft involve?

The industry has changed a lot for sure, and the team sizes have grown (although there are some very successful small-team indie games, too). But I wonder what this has meant not only for developers or games, but also for the big companies. As someone who both created games himself and has worked in director roles at EA and Microsoft, perhaps you could offer your perspective on this. Obviously, from what you said, business pragmatism was very important in those days as well. However, during all these years, have you noticed any evolution or change in the way big companies like EA operate? Relatedly, to what extent is a leadership role today different from what it was in the '90s?

Have you thought of going back to writing games yourself? After all, as you wrote in Tower of Myraglen, "some curves only turn you around in the end."

Thank you very much for your time.

Special thanks to felipepepe and Gragt for their help with the interview.

If you enjoyed this interview, be sure to check out the other ones in our retrospective interview series.

Imagine something like Wasteland -- a party-, skill-based top-down RPG -- that has you band together with famous historical and literary figures, from Genghis Khan to Hamlet, and explore, literally, the circles of Hell. Along the way, you fight the likes of Al Capone and Satan, learn new skills from Thucydides and Wyatt Earp, among many others, and solve your own and the denizens' problems, which Hell has in spades, with one overarching goal: escaping back to the real world.

As far as CRPG settings go, there has hardly been a more unorthodox one. Perhaps the only one directly comparable could've been Brian Fargo's Meantime, a canceled time travel RPG from the early 1990s (and, intriguingly, recently trademarked by Fargo again).

Unfortunately, Escape from Hell's original epic scope was cut down by the all too common constraints -- time, money, disk sizes, the usual -- and so only three of the originally planned nine circles made it in, and the multiple endings, innovative in their concept and variety, had to go, too. What remains, however, is still one of the most imaginative games from a highly creative CRPG era. I urge you to give it a try or, barring that, read my Let's Play.

To celebrate the game's anniversary, we've interviewed Richard Seaborne, who currently works at Microsoft, about Escape from Hell along with two other RPGs he worked on, Tower of Myraglen (1987) for the Apple ][GS and Prophecy: The Fall of Trinadon (1989) for the PC, the former a dungeon crawler with an overarching moral theme, nasty traps and ornate writing, and the latter a fairly large action RPG with a unique prefix-based spell system.

In the interview, Richard also talks about how he got into video game development, and the industry today compared to back then.

RPG Codex: To begin this interview, could you tell us a bit about how you got into video games, and computer role-playing games in particular? Did you come from pen and paper RPGs?

Richard Seaborne: The story may be a bit long but I hope it may inspire storytellers and game makers to stay true to their dreams and passion…

I’ve always loved games, ever since my parents took a loan out to buy an Apple ][ computer back in 1977 to teach themselves how to become programmers. I was about 10 years old then. In between their using the computer, I managed to get some time playing Breakout and Star Trek loaded from cassette tape. I found myself frustrated with both games, especially not being able to win Star Trek. My answer was to teach myself how to program Basic so I could modify the games and change the rules so that I had more photon torpedoes and abilities. I suppose it was my own Kobayashi Maru that made me see programming as a super power that could unlock things I wanted to achieve.

A few years later, my step-father took me to a hobby shop in an effort to find something we might connect over. That’s where I discovered Dungeons & Dragons, something that would change my life forever. My imagination lit up with D&D’s fantastic lore, intricate rules, and weaving of stories, puzzles, and combat into compelling challenges and quests. Over the years I found myself drawn to playing the role of Dungeon Master and crafting my own epic adventures for others to enjoy.

As I grew older, I wrote several D&D adventure modules and submitted them to TSR Hobbies, Inc. (the company behind Dungeons & Dragons) in hopes of being published, but was turned down (many times over despite my repeated submissions… all turned down). Two of my favorite D&D modules that I wrote were The Tower of Myraglen and The Gendorian Empire: The Fall of Trinadon. I also wrote a few computer games on the Apple ][ and submitted them to Apple and Broderbund Software, likewise in hopes of being published, but was declined. It was really disheartening, but I just loved role playing games and computer games. I couldn’t give up on my dream of telling stories and creating computer games.

Much later while in High School, I heard about the new Apple ][GS computer that was going to come out. I decided this was my chance to combine my learning from years of writing adventure modules and computer games (even if never published) to make a game on this new computer. I managed to get a summer job and save everything I earned to buy a ][GS and I relentlessly worked for over the next year to translate the adventure module of The Tower of Myraglen into a computer game on the Apple ][GS.

There was this little company called Electronic Arts (EA) that was a couple hours away from where I lived and so rather than mail in my submission of a yet unfinished game on the Apple ][GS (and likely get rejected again), I imagined it was possible to just show up and meet someone in the lobby. They would be so impressed they would publish my game. Well, that may have been naïve… but it actually worked… sort of!

I couldn’t find EA; their location wasn’t easy to find… it was in a new development, not on the maps I had. But then I stumbled upon PBI Software’s business sign hanging outside an industrial complex (as it turns out only a few blocks from EA). I recognized PBI from reading computer game magazines. Once inside their lobby, their President happened to hear me talking to the receptionist about my game and miraculously agreed to look at it right then. He said that if I would add features that took advantage of his company’s audio and memory cards, he would publish my game. I signed a contract with PBI Software to publish The Tower of Myraglen that very day, and went to town finishing it and added a lot of digital audio and effects to deliver according to my publishing terms.

I’ve always loved games, ever since my parents took a loan out to buy an Apple ][ computer back in 1977 to teach themselves how to become programmers. I was about 10 years old then. In between their using the computer, I managed to get some time playing Breakout and Star Trek loaded from cassette tape. I found myself frustrated with both games, especially not being able to win Star Trek. My answer was to teach myself how to program Basic so I could modify the games and change the rules so that I had more photon torpedoes and abilities. I suppose it was my own Kobayashi Maru that made me see programming as a super power that could unlock things I wanted to achieve.

A few years later, my step-father took me to a hobby shop in an effort to find something we might connect over. That’s where I discovered Dungeons & Dragons, something that would change my life forever. My imagination lit up with D&D’s fantastic lore, intricate rules, and weaving of stories, puzzles, and combat into compelling challenges and quests. Over the years I found myself drawn to playing the role of Dungeon Master and crafting my own epic adventures for others to enjoy.

As I grew older, I wrote several D&D adventure modules and submitted them to TSR Hobbies, Inc. (the company behind Dungeons & Dragons) in hopes of being published, but was turned down (many times over despite my repeated submissions… all turned down). Two of my favorite D&D modules that I wrote were The Tower of Myraglen and The Gendorian Empire: The Fall of Trinadon. I also wrote a few computer games on the Apple ][ and submitted them to Apple and Broderbund Software, likewise in hopes of being published, but was declined. It was really disheartening, but I just loved role playing games and computer games. I couldn’t give up on my dream of telling stories and creating computer games.

Much later while in High School, I heard about the new Apple ][GS computer that was going to come out. I decided this was my chance to combine my learning from years of writing adventure modules and computer games (even if never published) to make a game on this new computer. I managed to get a summer job and save everything I earned to buy a ][GS and I relentlessly worked for over the next year to translate the adventure module of The Tower of Myraglen into a computer game on the Apple ][GS.

There was this little company called Electronic Arts (EA) that was a couple hours away from where I lived and so rather than mail in my submission of a yet unfinished game on the Apple ][GS (and likely get rejected again), I imagined it was possible to just show up and meet someone in the lobby. They would be so impressed they would publish my game. Well, that may have been naïve… but it actually worked… sort of!

I couldn’t find EA; their location wasn’t easy to find… it was in a new development, not on the maps I had. But then I stumbled upon PBI Software’s business sign hanging outside an industrial complex (as it turns out only a few blocks from EA). I recognized PBI from reading computer game magazines. Once inside their lobby, their President happened to hear me talking to the receptionist about my game and miraculously agreed to look at it right then. He said that if I would add features that took advantage of his company’s audio and memory cards, he would publish my game. I signed a contract with PBI Software to publish The Tower of Myraglen that very day, and went to town finishing it and added a lot of digital audio and effects to deliver according to my publishing terms.

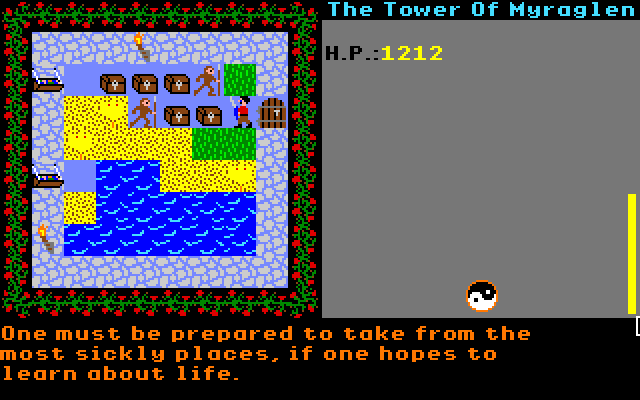

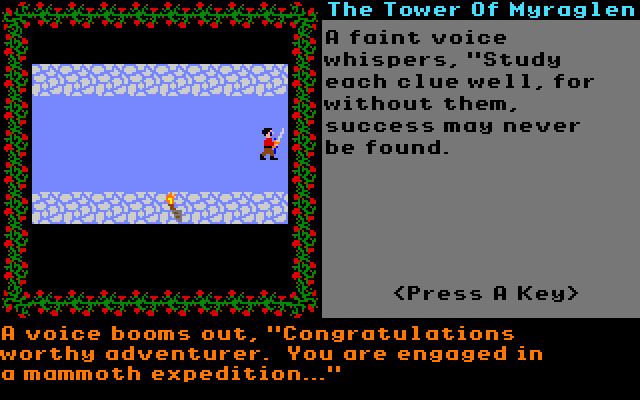

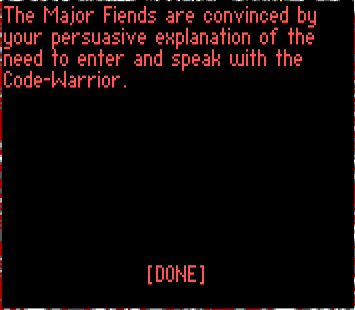

If I'm not mistaken, your first RPG was Tower of Myraglen (1987) for the Apple ][GS. It was a top-down action RPG taking place in a single dungeon and featuring some very ornate writing. How did the idea for the game’s concept and style originate?

That’s right, my first published RPG was Tower of Myraglen. It was actually based on an adventure module I wrote for Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) many years earlier. I always loved stories that put the player in conflict with contextual right and wrong, where their sense of ethical decisions change based on the situation.

The premise of Tower was that once a game changing power is possessed, how do you keep it in check? You know, absolute power corrupts… with great power comes great responsibility… The Arch Wizard defeated evil through creating the ultimate weapon (the medallion of soul stealing), only to find himself falling victim to his own desires and without consequence became his own worst enemy and gradually went mad. He locked himself and his uber weapon away so no one else could abuse the medallion or suffer the same situation. Of course, following fantasy tropes of the era, the player must retrieve the weapon to save the day against a new evil… and the cycle may repeat.

Inspired by games like Temple of Apshai and Ultima, I designed Tower’s top-down narrative interface to mirror the experience of playing D&D, with each room having a brief description, much as a Dungeon Master would detail, and laid out on screen like it might be on a “Battle Mat” with tile art, objects, characters, and monsters.

The premise of Tower was that once a game changing power is possessed, how do you keep it in check? You know, absolute power corrupts… with great power comes great responsibility… The Arch Wizard defeated evil through creating the ultimate weapon (the medallion of soul stealing), only to find himself falling victim to his own desires and without consequence became his own worst enemy and gradually went mad. He locked himself and his uber weapon away so no one else could abuse the medallion or suffer the same situation. Of course, following fantasy tropes of the era, the player must retrieve the weapon to save the day against a new evil… and the cycle may repeat.

Inspired by games like Temple of Apshai and Ultima, I designed Tower’s top-down narrative interface to mirror the experience of playing D&D, with each room having a brief description, much as a Dungeon Master would detail, and laid out on screen like it might be on a “Battle Mat” with tile art, objects, characters, and monsters.

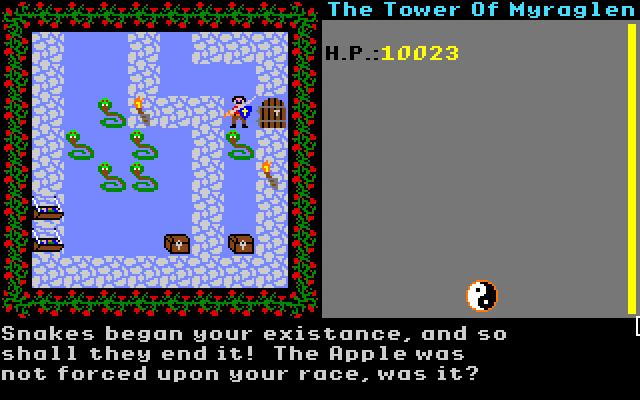

After Tower of Myraglen, you designed Prophecy: The Fall of Trinadon for the PC, published by Activision in 1989. It featured similar action-RPG gameplay to Tower of Myraglen, but with improved graphics, more complex character and inventory systems, and a large scope. Could you talk a bit about what your goals were with Prophecy? In particular, the graphics were really good for a 1989 DOS game – did a lot of effort go into that?

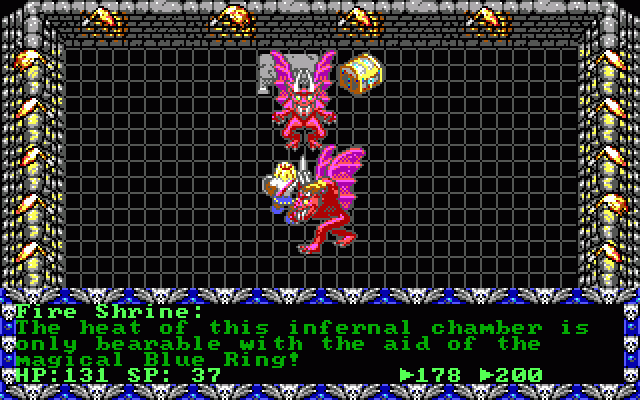

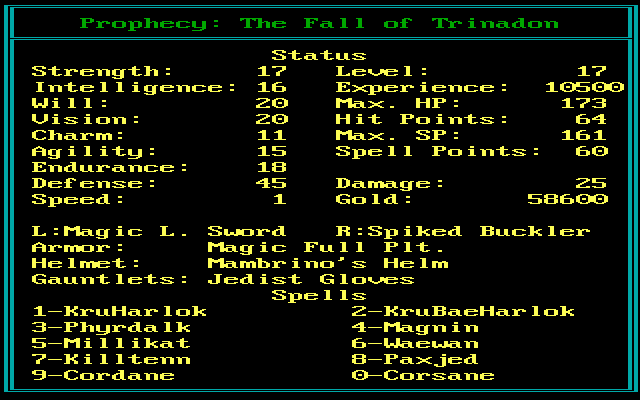

I really loved Prophecy: The Fall of Trinadon. It was based on a D&D module I wrote years before and refined through game play with friends. I wanted to make it into an action RPG that blended arcade action with role playing storytelling, inventory and gear evolution, skill progression, and spells. I really wanted the player to feel like their decisions, gear selection, and spell choices made a difference. I wanted the interface to be seamless with movement and combat happening quickly and automatically according to the situation.

The graphics had to be better looking and faster than I’d done before to make the experience feel immersive and support arcade action. I focused on taking advantage of the best graphics card of the time, 256-color MCGA/VGA, and dynamically down-res art to lesser video cards (16-Color EGA/TGA, 4-Color CGA). I was able to bring on Alan Murphy, one of the artists that worked on Atari’s Gauntlet, to create the art for Prophecy; he really upped the ante for visuals in the era, bringing coin-op arcade and fantasy genre art experience to personal computer games.

The graphics had to be better looking and faster than I’d done before to make the experience feel immersive and support arcade action. I focused on taking advantage of the best graphics card of the time, 256-color MCGA/VGA, and dynamically down-res art to lesser video cards (16-Color EGA/TGA, 4-Color CGA). I was able to bring on Alan Murphy, one of the artists that worked on Atari’s Gauntlet, to create the art for Prophecy; he really upped the ante for visuals in the era, bringing coin-op arcade and fantasy genre art experience to personal computer games.

Prophecy’s spell system was especially interesting. You could memorize up to 10 spells, and also increase their effects, etc. (including making the area of effect larger), by adding the proper prefix to the spell name. What made you go for a system like that?

Prophecy’s spell system was fun to make. I think people really enjoy controlling things where their decisions and actions materially change things in the games they play. And they delight in seeing their creations come to life or even blow up in surprising failure. The magic is that their actions had consequence, and they can get better. I wanted the player to feel like an alchemist that could craft their own magic spells according to consistent rules for any situation, seeing magic as a science they could control once learned.

I imagined players would really like having the ability to “program” their own spells through a spell language that included a prefix power amplifier, effect inverter, and foundational spell function. Spells included implicit properties (fire, ice, poison, harm, heal, etc.) and targeting (individual, missile, area of effect/AOE, etc.). A heal spell could be reversed with an inverter to make the spell harm, and a harm spell could be reversed to heal. Spells had a sense of physics too, so if you cast an AOE spell in too small of a space the blast would ricochet off walls and keep expanding through corridors until its “volume” filled its effect area. Adding the most powerful modifiers to an AOE spell could fill most of the screen with a powerful blast, which might be bad for the player if they were in the path of destruction.

I imagined players would really like having the ability to “program” their own spells through a spell language that included a prefix power amplifier, effect inverter, and foundational spell function. Spells included implicit properties (fire, ice, poison, harm, heal, etc.) and targeting (individual, missile, area of effect/AOE, etc.). A heal spell could be reversed with an inverter to make the spell harm, and a harm spell could be reversed to heal. Spells had a sense of physics too, so if you cast an AOE spell in too small of a space the blast would ricochet off walls and keep expanding through corridors until its “volume” filled its effect area. Adding the most powerful modifiers to an AOE spell could fill most of the screen with a powerful blast, which might be bad for the player if they were in the path of destruction.

The title screen for Prophecy says "Prophecy I: The Fall of Trinadon," which, I assume, means it was supposed to be the first game in a series. What were your plans for the sequel(s), and why did those plans not come to fruition?

Yeah, the game’s title was a real give-away about my hope of making Prophecy into a series.

Being an independent freelance developer without deep pockets added difficulty in delivering experiences that went beyond a single product. Publishers in the era sought to diversify their investment risk across different genres and typically wanted to see how a game performed at retail before signing a sequel or derivative game, leaving Prophecy II in a “wait & see” situation that I couldn’t afford to wait around. I had to find another publisher wanting an RPG in their portfolio, but due to contract terms with Activision for Prophecy, I wasn’t able to write its sequel for another publisher. And so there was no Prophecy II, leaving me to instead conceive Escape from Hell for Electronic Arts.

Being an independent freelance developer without deep pockets added difficulty in delivering experiences that went beyond a single product. Publishers in the era sought to diversify their investment risk across different genres and typically wanted to see how a game performed at retail before signing a sequel or derivative game, leaving Prophecy II in a “wait & see” situation that I couldn’t afford to wait around. I had to find another publisher wanting an RPG in their portfolio, but due to contract terms with Activision for Prophecy, I wasn’t able to write its sequel for another publisher. And so there was no Prophecy II, leaving me to instead conceive Escape from Hell for Electronic Arts.

Your next (and, as far as I know, last) RPG was Escape from Hell (1990). It has a very unorthodox setting: it is a role-playing game set - literally - in Hell, and it also lets you recruit famous historical individuals to your party. Was there any particular inspiration for the game's concept? Or did you simply grow tired of fantasy clichés typical to the genre?

I’ve always had a fascination with experiences that cast light on fundamental ideological conflicts of good and evil. You can see those elements in Tower and Prophecy. I’ve always loved the fantasy setting, but there’s just something really cool about the purity of Hell. The real question for me was the tone and flexibility of what the player can do in Hell…

Escape from Hell was originally envisioned as a serious RPG descent into The Inferno modeled after Dante’s Inferno, but evolved quickly away from the traditional tropes into a contemporary grim comedy that could instead poke fun at almost anything and break any rules people expect in a game or RPG. The player would likely relate more to a modern Hell, and let me create without the prescriptive dungeon crawler expectations – as you said, “anything goes”.

I found inspiration in the era from Larry Niven’s and Jerry Pournelle’s book Inferno, the comic Stig’s Inferno, movies Beetlejuice and Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, and a splash of Guns & Roses Appetite for Destruction. It really came down to trying to give the player things to believe in, to understand, and master… and then change it all up. I wanted people to be surprised at every turn, like “Seriously!? Shakespearean characters are trotting alongside Hitler to overthrow Al Capone, who happened to become an Arch Devil!?” (I really liked the audacity, if not insanity of the Escape from Hell storyline.)

Escape from Hell was originally envisioned as a serious RPG descent into The Inferno modeled after Dante’s Inferno, but evolved quickly away from the traditional tropes into a contemporary grim comedy that could instead poke fun at almost anything and break any rules people expect in a game or RPG. The player would likely relate more to a modern Hell, and let me create without the prescriptive dungeon crawler expectations – as you said, “anything goes”.

I found inspiration in the era from Larry Niven’s and Jerry Pournelle’s book Inferno, the comic Stig’s Inferno, movies Beetlejuice and Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, and a splash of Guns & Roses Appetite for Destruction. It really came down to trying to give the player things to believe in, to understand, and master… and then change it all up. I wanted people to be surprised at every turn, like “Seriously!? Shakespearean characters are trotting alongside Hitler to overthrow Al Capone, who happened to become an Arch Devil!?” (I really liked the audacity, if not insanity of the Escape from Hell storyline.)

Your list of inspirations for Escape From Hell is really interesting. You mentioned Dante’s Inferno, among other things, and there is also Shakespeare and his creations, various popular fictive characters, ancient philosophers, all gathered in the underworld. Did you research the subject for the occasion or did you already have an interest in it prior to making the game? Was it a natural thing to include that sort of content in video games 25 years ago or was Escape from Hell more of an exception even back then? Games like Wasteland did include all sorts of popular culture references, but not the comparable amount of historical and literary references, which certainly makes Escape from Hell stand out.

I definitely had a fascination with the concept of Hell, ancient philosophy, and literature, which helped a lot to get me started. But I had to do a lot of research to make the game. I purchased references and spent a lot of time at numerous libraries. I went through books, anthologies, compilations, art collections, and magazines. The rich historical materials mixed with contemporary culture was a trove of compelling content. The real challenge was sifting through it and conceiving a way to put it all together in a way people would find interesting.

Making lists and lists of characters, their loves & hates, what made them famous (or infamous in most cases), how they might manifest in Hell, and imagined interactions with their “fellow Hell mates” was fun. Riffing with others to hear their reactions to the ideas was critical to refining what worked and what didn’t. Of course, different people picked up on different things based on their own background and some things just resonated with a small subset of people (but in a big way). Ideas that were impactful generally made the cut and found their way into Escape.

I think RPG’s relied a lot on good stories back then because the graphics and sound were so much weaker than they are now, therefore they were more dependent on the content to inspire and reward the player’s imagination. I really enjoy games, movies, and TV that have historical or pop culture references. When people “get it” they feel a real sense of reward and accomplishment. Escape took that idea pretty far with indexing more heavily than most any RPG in its use of history, literature, and pop culture.

Making lists and lists of characters, their loves & hates, what made them famous (or infamous in most cases), how they might manifest in Hell, and imagined interactions with their “fellow Hell mates” was fun. Riffing with others to hear their reactions to the ideas was critical to refining what worked and what didn’t. Of course, different people picked up on different things based on their own background and some things just resonated with a small subset of people (but in a big way). Ideas that were impactful generally made the cut and found their way into Escape.

I think RPG’s relied a lot on good stories back then because the graphics and sound were so much weaker than they are now, therefore they were more dependent on the content to inspire and reward the player’s imagination. I really enjoy games, movies, and TV that have historical or pop culture references. When people “get it” they feel a real sense of reward and accomplishment. Escape took that idea pretty far with indexing more heavily than most any RPG in its use of history, literature, and pop culture.

How did Electronic Arts end up publishing Escape from Hell? Were they involved in the process of development, and did they influence the final product in any way?

I had always admired Electronic Arts (EA) for their game quality and innovation, and so pitched the concept of Escape from Hell to them not long after Prophecy had shipped. I learned quite a bit about formal planning and ideation while working with EA. I spent nearly six months of the total 12-month development cycle in pre-production, developing engine technology and tools that would ultimately be the foundation of the game and refining the concept with some of EA’s leaders including Trip Hawkins, Bing Gordon, and Dave Albert. It was during this process that Escape changed from a serious traditional RPG to the contemporary grim comedy RPG.

Perhaps the biggest influence that EA had on Escape from Hell was the business pragmatism of Cost of Goods (COGs) and Return on Investment (ROI). They made the decision to reduce the number of discs the game shipped on in half because retailers demanded the game be available on both 5¼” and 3½” discs. It was an unfortunate time in the industry where many computers had just one disc drive size, and so EA had to ship on both disc sizes. To keep costs down, they required Escape to get a lot smaller so the same COGs would cover both disc types.

You can imagine how that went down in terms of the game’s vision and scope – a lot less character and monster art, 9 circles of Hell collapsed to 3 planes of Hell, time & dimensional shift opportunity reduction, and a lot of loose end tying up with these changes. EA offered a Technical Director to help with compression algorithms to fit as much as possible on the discs and a professional writer to brainstorm and help the narrative be as cohesive as possible within the revised scope.

Perhaps the biggest influence that EA had on Escape from Hell was the business pragmatism of Cost of Goods (COGs) and Return on Investment (ROI). They made the decision to reduce the number of discs the game shipped on in half because retailers demanded the game be available on both 5¼” and 3½” discs. It was an unfortunate time in the industry where many computers had just one disc drive size, and so EA had to ship on both disc sizes. To keep costs down, they required Escape to get a lot smaller so the same COGs would cover both disc types.

You can imagine how that went down in terms of the game’s vision and scope – a lot less character and monster art, 9 circles of Hell collapsed to 3 planes of Hell, time & dimensional shift opportunity reduction, and a lot of loose end tying up with these changes. EA offered a Technical Director to help with compression algorithms to fit as much as possible on the discs and a professional writer to brainstorm and help the narrative be as cohesive as possible within the revised scope.

The text on Escape from Hell’s box went, "WARNING: Contains nudity, violence and controversial images." How did the label come about, and were you happy with it? Do you think it influenced the game's reception?

That label represents a pretty interesting moment in time for the video game industry (pre ESRB). Movies had been rated for some time already and music had begun using those kinds of warning labels. EA was progressive in supporting Escape from Hell’s violent gameplay, profanity, and some upper-body nudity but also thought consumers should be informed to prevent potential backlash. Of course, they also imagined it might be an advertising tool to entice people to check it out. The labeling actually worked against the game in the end, with a number of retailers and even international regions declining to sell it.

Just like Fountain of Dreams (also published by EA in 1990), Escape from Hell’s presentation (from the overworld exploration and skill use to animated enemy portraits) looks very similar to another EA game, Wasteland (1988). A lot of websites simply assume Fountain and Escape used the Wasteland engine, but when I asked Brian Fargo about it recently, he told me that probably wasn’t the case since, in his words, “the Wasteland engine could barely be called an engine with all the hand coding you had to do.” He did not, however, completely exclude the possibility that some of the Wasteland code might have been used (even if he considered that improbable, too). Can you shed some light on that? Did you build Escape from Hell's engine from the ground-up, and do you know how much of the code was inherited from Wasteland?

I wrote Escape from Hell entirely from the ground up, using no code or tools from Wasteland or any other game. Although there’s no shared ancestry with Wasteland, I have to say that I’ve never minded the comparison because it was a great game. Actually, EA leveraged some of Escape’s down-res rendering code for other games.

It’s interesting to note that EA’s Executive Producer for Wasteland, Fountain, and Escape was the same person – Dave Albert. He was a great champion for EA’s RPG’s.

It’s interesting to note that EA’s Executive Producer for Wasteland, Fountain, and Escape was the same person – Dave Albert. He was a great champion for EA’s RPG’s.

Escape from Hell has a number of fairly unique features. One of those is using special tridents, scattered across Hell, to shape the environment by altering the surrounding landscape and time frame. The idea of shaping the gameworld to your advantage or disadvantage remains, I believe, fairly underexplored even today. Was this feature implemented as fully as you had initially envisaged it?

Escape from Hell was an open-world design with the player being able to explore as much or as little as desired to finish the game, offering opportunity to go back and replay with different party combinations, gear, and quest choices to see what might happen differently.

The Tridents were another vehicle for the player to change things up, controlling combat difficulty and encounter outcomes by cleverly manipulating the “world” and technology levels. The Trident concept to re-shape the world and time frame was something I would’ve loved to have done more with, but became difficult to employ effectively within the reduced three planes of Hell (instead of the envisioned nine circles).

The Tridents were another vehicle for the player to change things up, controlling combat difficulty and encounter outcomes by cleverly manipulating the “world” and technology levels. The Trident concept to re-shape the world and time frame was something I would’ve loved to have done more with, but became difficult to employ effectively within the reduced three planes of Hell (instead of the envisioned nine circles).

The game has an "anything goes" tone, but there also seems to be a certain logic behind it. The first few locations do a good job of showing Hell as an organized place, going the "Hell is a bureaucracy"/"bureaucracies are hell" route. The Hell Guard camp and Limbo go a long way of communicating that even in Hell, there are rules. Then Lucifer's Landing just gets blown up on a whim. After that, the illusion of an all-pervasive order is further ruined as we are introduced to the local struggle for power and revenge between Al Capone and Caesar, as well as to Hitler's plans for a coup. Am I overthinking this? I guess I'm just curious to know if there was a plan behind all this hellish madness.

One of the story tenets I’ve always looked at is to establish a backstory that is understandable, predictable, and resonates with some basic values… and then pull the rug out from under it so the player wants to right the wrong and set things back to the way they were.

The first level of Escape from Hell can be pretty overwhelming as an open-world RPG with a lot of things to do, places to go, gear to get, and NPC’s to acquire. The hope was that giving structure to the player’s first experience in Hell would help them adapt to the game and build expectations on how the game would proceed, anticipating the game would likely be a traditional gear up, complete quests, and kill the boss experience. The idea that Lucifer could just wipe out an entire city at a whim shattered the sense of security and predictability; the world was not “safe” or stable. Discovering there are underground movements opposing Lucifer was both ironic and tried to give the sense that maybe Lucifer was also not quite so all-seeing or all-powerful either. Finding out that some NPC’s would not adventure with others, or had opinions on things you did and places you went was intended to make the world feel alive.

So, was there a plan? Yes, sort of… mostly the vision was to setup a baseline, shatter it, put a new baseline, reset it, and so on. After all, that’s what Hell is…

The first level of Escape from Hell can be pretty overwhelming as an open-world RPG with a lot of things to do, places to go, gear to get, and NPC’s to acquire. The hope was that giving structure to the player’s first experience in Hell would help them adapt to the game and build expectations on how the game would proceed, anticipating the game would likely be a traditional gear up, complete quests, and kill the boss experience. The idea that Lucifer could just wipe out an entire city at a whim shattered the sense of security and predictability; the world was not “safe” or stable. Discovering there are underground movements opposing Lucifer was both ironic and tried to give the sense that maybe Lucifer was also not quite so all-seeing or all-powerful either. Finding out that some NPC’s would not adventure with others, or had opinions on things you did and places you went was intended to make the world feel alive.

So, was there a plan? Yes, sort of… mostly the vision was to setup a baseline, shatter it, put a new baseline, reset it, and so on. After all, that’s what Hell is…

The game is also subversive in that it makes use of some well-known mass murderers. There’s Al Capone, still a boss of the underworld albeit a different kind, and then there are Stalin and Hitler. I find these two interesting because most retrospectives about EFH tend to insist a great deal on the presence of Hitler—found in Dachau no less!—and get seemingly offended by the fact that he can be recruited as a party member, yet very little attention is paid to Stalin, available for recruitment at the start of the game. And Hitler would again appear in a video game two years later in Id Software’s Wolfenstein 3D, this time in the much more acceptable role of the final boss of the original game. Did you expect some controversy to spring up from the use of Stalin and Hitler? Was there even any reaction to that at the game’s release? Is there any reason that pushed you to sort some of these characters as villains (Al Capone) and others as allies (Hitler, Stalin)?

There was little reaction to most characters in Escape except for Hitler that I recall. I expected there might be negative reactions to characters who were in Hell that people felt did not belong there at all, but never thought there’d be a negative reaction to infamous characters like Hitler being in Hell because, well, THEY SHOULD BE IN HELL by most people’s opinions. The idea that you could recruit Hitler into your party was something that seemed to fit the outlandish premise of Escape. It just seemed like the perfectly absurd thing to do…

A bit of trivia here… Some people did anticipate there’d be a negative reaction to Hitler being in Hell and recruitable and encouraged me to make some changes in the game (which I did). The pentastar devil banner found throughout Hell included versions with swastikas in Hitler’s areas as a sign of his underground movement’s influence, but the feeling was that it made him appear “successful” in Hell, which was going too far. I ended up removing them from the game.

There wasn’t a logic for which characters would be recruitable beyond where the story made sense at the time. For example, I initially imagined Al Capone would run an entire underground smuggling operation using speakeasies as secret meeting places. But later I decided that Hitler running an underground resistance movement against the Devil was more interesting and would have broader awareness and offer more irony. The process was not nearly as logical as it could’ve been, I suppose… Instead, decisions were based on what felt more interesting at the time.

In the end, games, movies, TV, books, comics, etc., are fiction meant to entertain, inspire, and evoke emotions. Maybe they just pass the time, or maybe they teach us something. But they are fiction. I feel for those people who were offended; Escape was never intended to offend anyone or make any political statements. Escape sought to be fun and entertaining, in an absurd context. Nothing more than that.

A bit of trivia here… Some people did anticipate there’d be a negative reaction to Hitler being in Hell and recruitable and encouraged me to make some changes in the game (which I did). The pentastar devil banner found throughout Hell included versions with swastikas in Hitler’s areas as a sign of his underground movement’s influence, but the feeling was that it made him appear “successful” in Hell, which was going too far. I ended up removing them from the game.

There wasn’t a logic for which characters would be recruitable beyond where the story made sense at the time. For example, I initially imagined Al Capone would run an entire underground smuggling operation using speakeasies as secret meeting places. But later I decided that Hitler running an underground resistance movement against the Devil was more interesting and would have broader awareness and offer more irony. The process was not nearly as logical as it could’ve been, I suppose… Instead, decisions were based on what felt more interesting at the time.

In the end, games, movies, TV, books, comics, etc., are fiction meant to entertain, inspire, and evoke emotions. Maybe they just pass the time, or maybe they teach us something. But they are fiction. I feel for those people who were offended; Escape was never intended to offend anyone or make any political statements. Escape sought to be fun and entertaining, in an absurd context. Nothing more than that.

Escape from Hell sometimes hints at alternative endings that don’t seem to have been implemented. The message you get when recruiting Blonde suggests the possibility of rescuing her from Hell instead of Alison, "the catastrophic effects it would have on Alison," and "the absolute destruction of the fabric of the mortal universe that would occur by bringing a being that cannot be killed into it." Similarly, warning you against teaming up with Hitler, Charon implies that Satan may "irrevocably obliterate every last of them, maybe even the entire circle of Hell" if you bring Hitler to the Devil's Fortress. Were any of these endings even planned?

Yes, some of those scenarios and alternate endings were originally part of the vision. Some were just written into the script to hint and inspire imagination. I have to admit, too, that some fell on the cutting room floor due to scope changes by design and some I just forgot or missed.

I left some things specifically open ended in hopes of using them in a sequel, Hell on Earth, based on the premise that the Gates to Hell were not closed properly and all those NPC’s you interacted with entered the mortal world wreaking mayhem and requiring the player deal with the mess they made.

I left some things specifically open ended in hopes of using them in a sequel, Hell on Earth, based on the premise that the Gates to Hell were not closed properly and all those NPC’s you interacted with entered the mortal world wreaking mayhem and requiring the player deal with the mess they made.

Speaking of endings, an obvious bad ending could have involved being evil enough for the gates of Hell not to let you out. Messing around with the game's files in a hex editor, I came across a hidden attribute that would fit that kind of ending, called “Alignment.” What is the story behind it?

You’re right, the game tracked a number of stats; not all were visible. The entire game was built atop its map, combat, and script engine. The script engine allowed any message or event to be “programmed” to branch or trigger according to “stat” values. Alignment was very much a “goodness” spectrum rating stat, much like D&D.

It’s been a while, but I recall alignment was intended to allow or disallow entire story sequences, choices, and NPC’s joining/not joining. I wanted every action to have a consequence, but found that often the subtlety of invisible stats like alignment felt like bugs at times and so I don’t remember it being used much at all in the game. In retrospect, I think there was some great opportunity to do a lot more around alignment.

It’s been a while, but I recall alignment was intended to allow or disallow entire story sequences, choices, and NPC’s joining/not joining. I wanted every action to have a consequence, but found that often the subtlety of invisible stats like alignment felt like bugs at times and so I don’t remember it being used much at all in the game. In retrospect, I think there was some great opportunity to do a lot more around alignment.

In general, there are some locations and subplots in Escape from Hell that I thought felt somewhat unfinished. How many of the features, quests, skills, items, etc., did you have to scrap? Could you name some of the more interesting content that you could not or did not have time to implement?

As we’ve talked about, six out of nine circles of Hell didn’t make it. We’ll all have to imagine the other six levels right up to the frozen wastelands of the Ninth Circle… and the many characters, monsters, demons, and items spread across them.

I think the biggest thing missing beyond the sheer size of the game is the lost artwork that forced a lot of re-used visuals, even for signature characters.

I think the biggest thing missing beyond the sheer size of the game is the lost artwork that forced a lot of re-used visuals, even for signature characters.

Escape from Hell was released in January 1990, so that January 2015 marks its 25th anniversary. I'm very interested in the way you feel about the game now. Let me put it this way: what is your first thought whenever the game's name comes up? Retrospectively, are you fully satisfied with what kind of game Escape from Hell turned out to be?

Disappointed. Disheartened. Proud. It’s a bit mixed as you can tell.

Escape shipped and had its place in history. I firmly believe it would have been better if it hadn’t had its media budget cut in half, forcing it to miss out on all Nine Circles of Hell, signature art for key characters, more demons, monsters, & gear, and more map & script variances according to player actions, party members, and Trident time control. On the other hand, I am proud to have contributed to the early era of CRPG’s, influencing a lot of features, design tenants, and concepts in many games over these twenty-five years.

Escape shipped and had its place in history. I firmly believe it would have been better if it hadn’t had its media budget cut in half, forcing it to miss out on all Nine Circles of Hell, signature art for key characters, more demons, monsters, & gear, and more map & script variances according to player actions, party members, and Trident time control. On the other hand, I am proud to have contributed to the early era of CRPG’s, influencing a lot of features, design tenants, and concepts in many games over these twenty-five years.

You said you were refining the game's concept with EA’s senior people like Trip Hawkins (the founder and CEO), Bing Gordon (who, from what I've gathered, was EA's head of marketing and also an occasional project manager at the time), and Dave Albert (the producer). I'd be curious to hear how those meetings went, how frequent they were, and what kinds of things those people would push for. In general, what was the dynamics of the creator - producer - marketing department - CEO relationship back in those days?

Although my contract gave me complete creative control, there was a lot more to making a game with a publisher back then. I needed to pass the publisher’s milestone reviews for creative, art, software builds, documentation, and business (ROI). The publisher owned packaging, art, and materials. The publisher’s marketing team had to love Escape and know how to position it to retail and consumers alike. I just wanted to make games, but this was a serious business about fun and entertainment. The result was a lot of interaction with many people with different levels of influence, which in many ways, was control.

The amount of time spent with each person varied. It’s been a while, so from what I recall...

Trip was involved only a few times directly, mostly in concept and milestone reviews. He seemed focused on making sure the game could be successful at retail, added value to the company’s portfolio, was innovative and of quality, and ultimately would yield return on investment. The biggest thing beyond greenlighting Escape at each review was Trip’s awesome 2-page document that he wrote detailing good game design considerations. It asked a lot of key questions that helped guide decisions for characters, storylines, control mechanics, user interface, graphics, game rules, progression, reward systems, etc.

Bing was involved directly and indirectly. He seemed to like being close to products and, because he was super creative, got excited about Escape due to its wide open creative setting. He had more ideas than I could keep up with; they seemed to just flow forth effortlessly. Some ideas felt, at the time, too wild for even Escape… but when I reflect back on everything I really wish I would have incorporated more of his ideas. There are few people I can ascribe the word genius to, but Bing was one of them.

Dave was a real champion for developers and RPG’s, and so was a perfect interface for independent freelancers to the publisher. He was an objective voice, a game editor, and an avid gamer that functioned as my ally and corporate interface. I met with Dave every week, sometimes twice a week. He kept EA informed on development progress and me informed of what marketing, business development, and executive views were. Most importantly, Dave gave me design and story feedback throughout development.

The amount of time spent with each person varied. It’s been a while, so from what I recall...

Trip was involved only a few times directly, mostly in concept and milestone reviews. He seemed focused on making sure the game could be successful at retail, added value to the company’s portfolio, was innovative and of quality, and ultimately would yield return on investment. The biggest thing beyond greenlighting Escape at each review was Trip’s awesome 2-page document that he wrote detailing good game design considerations. It asked a lot of key questions that helped guide decisions for characters, storylines, control mechanics, user interface, graphics, game rules, progression, reward systems, etc.

Bing was involved directly and indirectly. He seemed to like being close to products and, because he was super creative, got excited about Escape due to its wide open creative setting. He had more ideas than I could keep up with; they seemed to just flow forth effortlessly. Some ideas felt, at the time, too wild for even Escape… but when I reflect back on everything I really wish I would have incorporated more of his ideas. There are few people I can ascribe the word genius to, but Bing was one of them.

Dave was a real champion for developers and RPG’s, and so was a perfect interface for independent freelancers to the publisher. He was an objective voice, a game editor, and an avid gamer that functioned as my ally and corporate interface. I met with Dave every week, sometimes twice a week. He kept EA informed on development progress and me informed of what marketing, business development, and executive views were. Most importantly, Dave gave me design and story feedback throughout development.

You developed games for Apple ][GS (Tower of Myraglen, Sea Strike, Monte Carlo) and then for DOS (Prophecy, Escape from Hell). What was your experience moving from one platform to the other?

The PC was much easier and faster to develop for, sporting much more processing horsepower and professional mature tools. The PC compiler and assembler to write code was so much better than the Apple had; the PC was a professional platform for developers where Apple felt like a hobbyist platform.

Although the PC was faster than the ][GS, it was more complicated to support graphically due to it having so many different graphics card options. I spent quite a while writing graphics drivers and rendering solutions just to support so many different video cards. For nostalgic techies out there - the PC was much faster with at least a 4.77Mhz 16bit processor (most people had 7.16Mhz or better) while the ][GS had a 2.8Mhz 65C816 16bit processor.

Although the PC was faster than the ][GS, it was more complicated to support graphically due to it having so many different graphics card options. I spent quite a while writing graphics drivers and rendering solutions just to support so many different video cards. For nostalgic techies out there - the PC was much faster with at least a 4.77Mhz 16bit processor (most people had 7.16Mhz or better) while the ][GS had a 2.8Mhz 65C816 16bit processor.

For Tower of Myraglen and Prophecy, you collaborated with two graphical designers, Jeff Lefferts and Alan Murphy respectively. Alan worked with you on Escape from Hell, too, whose full title even reads “Richard & Alan’s Escape from Hell.” Could you tell us a bit about Jeff and Alan, and how you got to work with them?

Jeff Lefferts was a buddy from High School that played Dungeons & Dragons with our gaming crew, and when I was writing The Tower of Myraglen he offered to do the art for the game. It was great to create my first game with a friend.

Alan Murphy had been a professional video game artist with credits on one of my favorite coin-op arcade games, Atari’s Gauntlet. I met Alan during my work on Prophecy: The Fall of Trinadon. He was not only a great artist, but a really cool dude. Our industry was different then… I remember signing the contracts for Prophecy and Escape on the beaches in Santa Cruz and Capitola in California, respectively. We would riff about “what might be in Hell” and design ideas on the coast, enjoying drinks in beachside pubs and cafes…

Alan Murphy had been a professional video game artist with credits on one of my favorite coin-op arcade games, Atari’s Gauntlet. I met Alan during my work on Prophecy: The Fall of Trinadon. He was not only a great artist, but a really cool dude. Our industry was different then… I remember signing the contracts for Prophecy and Escape on the beaches in Santa Cruz and Capitola in California, respectively. We would riff about “what might be in Hell” and design ideas on the coast, enjoying drinks in beachside pubs and cafes…

How did you end up going from coding and designing games – from creating your own games, basically – to, it would seem, focusing more on the technical and managerial aspects in the 1990s and 2000s, as Technical Director, Project Manager, and Studio Manager with EA and Microsoft? What does your current work at Microsoft involve?

I love making games and all the complexities therein, balancing design, scope, and technology with production. The industry has changed a lot since I wrote my first games. Many companies have gone out of business, and a few have become hubs of publishing and development.

Games like Escape from Hell were one of the last “small team” games. Team sizes have climbed from a few people to hundreds of people. In order to drive quality and innovation, I decided to take on product and technology leadership roles. I’ve had to learn very different skills to manage and scale through others, but have found the fundamental principles of video game design and development remain true and scale to any team size. The biggest difference in my leadership roles is being less of an individual doer and more of an overall mentor, influencer, shaper, and reviewer that empowers others to pursue their passions and own and drive greatness. It’s a great job, being so close to entertainment, games, and awesome technologies… working with amazingly creative and smart people.

Games like Escape from Hell were one of the last “small team” games. Team sizes have climbed from a few people to hundreds of people. In order to drive quality and innovation, I decided to take on product and technology leadership roles. I’ve had to learn very different skills to manage and scale through others, but have found the fundamental principles of video game design and development remain true and scale to any team size. The biggest difference in my leadership roles is being less of an individual doer and more of an overall mentor, influencer, shaper, and reviewer that empowers others to pursue their passions and own and drive greatness. It’s a great job, being so close to entertainment, games, and awesome technologies… working with amazingly creative and smart people.

The industry has changed a lot for sure, and the team sizes have grown (although there are some very successful small-team indie games, too). But I wonder what this has meant not only for developers or games, but also for the big companies. As someone who both created games himself and has worked in director roles at EA and Microsoft, perhaps you could offer your perspective on this. Obviously, from what you said, business pragmatism was very important in those days as well. However, during all these years, have you noticed any evolution or change in the way big companies like EA operate? Relatedly, to what extent is a leadership role today different from what it was in the '90s?

Big games and correspondingly big teams just didn’t exist in the ’90s. There are teams of all sizes today, big and small, working on games of all sizes. There are far fewer big bets on huge games, but when they pay off, a new franchise is born or continues on. The development process and team management is necessarily different according to product and team size.

Small and big companies in the ‘90s and today share the same goal of making fun and entertaining experiences people want. They keep trying different approaches to find and cultivate sparks that become awesome games. There’s been a lot of evolution and churn in how big companies operate. Regardless of how things change though, at its core passionate people make great things. Big companies just have different problems than small companies, most notably how to inspire and empower passion within big distributed organizations that operate under deadlines and business performance targets.

Leadership and operations are closely tied, as your question poses… Being true to the game and who you are is the most important thing in leadership, whether it was in the ‘90s or now. I know that I’ve unintentionally offended people by saying contrarian views over the years, but I like to believe I’ve inspired others, too, by being forthright in what I think. Leadership, to me, is about inspiring and empowering others, being committed and taking risks alongside the team, driving accountability, setting goals, defining possible steps to achieve them, formalizing success measures, and establishing context for how people will work together. My leadership style has evolved over the years as I’ve adapted from small teams to large teams.