RPG Codex Review: Blackguards 2

RPG Codex Review: Blackguards 2

Review - posted by Crooked Bee on Fri 6 March 2015, 19:54:42

Tags: Blackguards 2; Daedalic EntertainmentAs every German denizen of the Codex knows, deutsche Rollenspiele sind ausnahmslos ein Grund zur Freude. So it was in Blackguards' case, too, which made us genuinely happy. Can we say the same about Blackguards 2? Of course we can, especially when it is reviewed by esteemed community member Bubbles - an authentic German and a true patriot:

Read his review, replete with fitting captions and insightful commentary, and share in his pride and joy. See him cut to the chase:

Or analyze the strategic minutiae while never losing sight of the bigger picture:

Not to mention taking the game's knee-jerk detractors to task:

Only to deliver the pointed, well thought-out conclusion:

Are you man enough to enjoy Blackguards 2? The full review - one of our best to date, if you ask me - has all the answers: RPG Codex Review: Blackguards 2

The German people take pride in excellence. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the quality of German RPGs: from the classic Realms of Arkania trilogy through the transgressive Albion and the ground breaking Ambermoon to the blockbuster Gothic and Risen franchises, the thread of German game design winds through the very DNA of role play gaming. Even the greatest American games draw upon German talent: who could imagine a Planescape: Torment without Guido Henkel, or a Pillars of Eternity without J.E. Sawyer? Germany's game developers have taken their work ethic from the manual labourers who built the Autobahn and dug the great coal pits of the Ruhrgebiet: they labour in the service of a greater good, striving tirelessly towards perfection.

Read his review, replete with fitting captions and insightful commentary, and share in his pride and joy. See him cut to the chase:

Blackguards 2 is simpler, sleeker, slimmer than its predecessor; it is a mellow sort of game.

Or analyze the strategic minutiae while never losing sight of the bigger picture:

In fact, Blackguards 2 nicely facilitates aggressive gameplay by removing all death penalties and auto-healing and resurrecting your group after every battle, even when they are isolated in the middle of a dungeon. In the first game, players were forced into a resource management metagame that required them to sacrifice resources (money, potions, or camping supplies) to regenerate missing hp and mana and cure the “wounds” debuff after battle. The problem with this system was obvious: if you spent all your money, drank all your potions, wasted your camping supplies by resting after every battle, and then had to sell your weapons to be able to afford healing, you might end up in a situation where it was absolutely impossible to progress in the game. As a hardened veteran of German RPGs I never encountered any problems with this system myself, but it is easy to imagine a less conscientious fan from the new world running into severe trouble with this kind of dead end mechanic.

Not to mention taking the game's knee-jerk detractors to task:

The game's detractors have made great sport of the fact that the scope of the optional content in BG2 does not come close to the amount and variety of side quests in even just the third chapter of the original Blackguards. However, this decreased focus on optional content has given Daedalic more time to work on the most complex features of the core game; specifically, on the boss fights and the AI, as well as on the core cast of characters and the story itself.

Only to deliver the pointed, well thought-out conclusion:

Playing Blackguards 2 after Blackguards 1 is remarkably similar to the experience of playing Dragon Age 2 after Dragon Age: Origins. Some players will prefer the first game for its sheer volume and “old school” flair, while others will be drawn to its sleeker, more assured successor. Some will appreciate BG2's greater focus on storytelling, its unique depiction of mental illness, the tightly progressing story suffused with a malodorous air of inevitability, the greater emphasis on companion interactions, the deft use of negative space in map design as well as in character development, and the tight focus on high-density, high-volume wave combat.

Are you man enough to enjoy Blackguards 2? The full review - one of our best to date, if you ask me - has all the answers: RPG Codex Review: Blackguards 2

[Review by Bubbles]

The German people take pride in excellence. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the quality of German RPGs: from the classic Realms of Arkania trilogy through the transgressive Albion and the ground breaking Ambermoon to the blockbuster Gothic and Risen franchises, the thread of German game design winds through the very DNA of role play gaming. Even the greatest American games draw upon German talent: who could imagine a Planescape: Torment without Guido Henkel, or a Pillars of Eternity without J.E. Sawyer? Germany's game developers have taken their work ethic from the manual labourers who built the Autobahn and dug the great coal pits of the Ruhrgebiet: they labour in the service of a greater good, striving tirelessly towards perfection.

In recent years, Daedalic Entertainment, based in Europe's cultural capital of Hamburg, Germany, has applied this work ethic to the adventure genre. Today, Daedalic are virtually the only remaining major developer of complex and well-written adventure games. Imagine, then, what such a team of professionals, masters in marrying complex gameplay to transcendent storytelling, could achieve in the exalted sphere of role play gaming. After years of public exhortations, Daedalic finally made their first cautious entry into the RPG genre in early 2014. Blackguards was a well-received sleeper hit that offered players an intriguing combination of tactical turn based combat with a harrowing story of death, betrayal, and heroism, built on the foundation of the German “The Dark Eye” setting (in essence, a subtly tweaked and expanded version of the American “Dungeons and Dragons” system).

Blackguards was not a perfect game: its provocatively challenging gameplay proved a turn-off to those who found no joy in complexity, while the game's laser-like focus on a simple, linear, yet wholly sufficient central narrative served to alienate dedicated explorers, romantic souls, and compulsive collector types alike. Blackguards's strengths, however, were in areas that had long since lain fallow in modern RPGaming: it offered a remarkable amount of freedom in character creation and development that put any party based game since the Realms of Arkania trilogy to shame. While the game consisted almost entirely of combat (and at least 40 hours worth of combat at that), the designers did their utmost to make every encounter unique, challenging, and – in my purely subjective opinion – quite simply interesting to play through. The standards that Blackguards has set in encounter design will very likely remain an industry benchmark for generations to come.

Now, less than one year later, Daedalic has released Blackguards 2. Their design approach was different this time around. Almost every aspect of the gameplay has undergone a radical change; generally speaking, these changes involved cutting out the most daunting and complex gameplay mechanics, and replacing them with simpler, more accessible substitutes.

Let us start with the areas where the changes are most obvious:

Character Creation and Development

In the first Blackguards, a character's base attributes directly influenced every aspect of their combat performance. A warrior with high Strength hit for more damage, even with weapons he had little training in; a mage with high Constitution had a better chance of resisting wound debuffs and status effects. Success rolls for spell casters also checked attributes; a spell that emphasized physical effects may have rolled against the caster's Strength, while an illusion spell may have checked their Charisma. Finally, passive perks and new combat moves were only unlocked for purchase based on hard attribute requirements.

The spell system added a further intricacy by attaching different xp costs to improving different spells, based on the spell's power. Burst of Flame – mostly a single target spell – was cheaper to improve than the large AoE spell Fireball. In a game with no xp grinding opportunities, this mechanic encouraged you to gauge whether the more powerful spells were indeed worth the investment, or whether you would be better off diversifying your tactical portfolio by investing in multiple cheaper spells. This was especially important since spells could fail; trying to cast a spell that checked attributes your mage had neglected (like Strength) required you to make a substantial xp investment in the spell just to achieve a 60 or 70% success rate. Since even a spell with a 70% success rate could potentially fail hundreds of times in a row, this system could occasionally be extremely frustrating; still, it worked well enough in the absence of better alternatives.

One particular wrinkle of the system was that attributes could be directly increased with xp, just like talents and spells; thus, you might get into a situation in which increasing your Intelligence improved a mage's prowess with Intelligence-based spells more than directly investing xp in those spells would have done, while also unlocking further perks. Simply put, the character system rewarded careful and methodical thinking. Conversely, distributing your xp without much thought could make for an immensely joyless gameplay experience.

Blackguards 2 scuttles all of these mechanics with an admirable clarity of purpose. Attributes have been removed. All spells cost an equal amount of xp, though they are by no means equally useful. Most Spells cannot fail at all. Meanwhile, weapons have a higher base to-hit chance even at low talent values and are also easier to master, since increasing a weapon talent now automatically grants the damage bonus – along with other perks – that used to be tied to strength and other attributes. Blackguards 2 is simpler, sleeker, slimmer than its predecessor; it is a mellow sort of game.

Simplicity, though much maligned in hardcore circles, is by no means a bad thing in and of itself – it helps games attract a broader demographic, reduces the potential for frustration, and can provide young gamers with a safe space to learn the basics of turn-based gameplay in a fun and entertaining manner. Moreover, simplifying complex mechanics can make a game much easier to balance. The first Blackguards had so many moving parts and interdependencies that some simplification in the service of creating a more balanced game might have been a very fine idea indeed.

Blackguards 2 is not, objectively speaking, more balanced than its predecessor. One paradigmatic example of BG2's various minor imbalances is the handling of magic-capable PCs. In the first game, the player was presented with a choice of whether his new character would be able to cast spells or not. A non-magic capable character would never be able to cast a single spell, but they had more xp to spend on physical talents and could wear heavy armour without penalties. A pure mage would have more burst damage power, but could run out of mana quickly, was weakly armoured, and had limited long-term damage potential. A hybrid character combining magic and some weapon talents could potentially be stronger than either of the pure options, but was more difficult to build due to relying on many different attributes and suffering harsh spellcasting penalties in iron armour.

In Blackguards 2, the main character Cassia starts as a magic-capable character with no xp penalty. Iron armour penalties only reduce the size of a character's mana pool and their mana regeneration (there is no spell failure after all) and can be completely removed by buying two perks that together cost less than mastering a single spell. If one chooses not to take these perks, one will still have enough mana to cast a buff spell or two per battle. There is also another perk that gives you extra armor if you have learned three spells. It is easy to see the value behind these changes: mages were more interesting to build in the first game, and playing interesting games is fun. Ergo, every player character can learn magic in the second game. And since every PC can cast spells, penalties for spell casters should be reduced, so that casting spells is fun even for people who prefer to play fighters. The logic is sound.

Have pure physical fighters been buffed to compensate for these changes? No. Instead, Blackguards 2 introduces a new stamina mechanic that functions exactly like mana (this seems a misstep, since it actually makes the game more complex) and limits the amount of special attacks a warrior can perform per battle. Special attack spam was the core gameplay mechanic for physical fighters in the first game, mainly balanced by the fact that the specials could decrease your hit chance against high-defense targets so far that using standard attacks or changing targets was occasionally preferable. Now, with the generally increased hit chance, this would no longer have been a viable balancing strategy; thus, Daedalic employs the stamina mechanic to introduce variety in gameplay.

A new character has 40 stamina, and 1 stamina regeneration per turn; the most useful special attacks cost at least 10 stamina. In practice, this means that physical fighters spend a lot of time auto attacking while waiting for their stamina to regenerate. It is up to the individual player to decide whether spamming auto attacks is superior to spamming special attacks, and I will pass no judgement on this matter.

The biggest positive change for warriors has been a much-requested fix to weapon damage; while the first game rolled “virtual dice” and left frustrated players burning their virtual game boxes after getting multiple bad rolls in a row, Blackguards 2 simply offers up a single number of sublime simplicity – you always hit for the same amount before damage resistances. No fuss, no mess, easy come, easy go.

On that note, the armour system has been changed from the flat absorption + percentage reduction hybrid system of the first game to purely percentage based resistances. This has served to make the armour mechanics much more accessible for neophyte players, who notoriously had to rely on a fan written manual to make even the slightest amount of sense of the Blackguards 1 system. Daedalic has further reduced any chance of confusion by including a sleek new stat summary on the inventory screen that immediately shows you character resistances, regeneration, and weapon damage. It is the most obvious change to the game's UI, and it is a very good one.

Archers, meanwhile, now have an ambush/overview mechanic that elevates their gameplay options almost to the level of a gun fighter in Shadowrun Returns (though the stamina mechanic unfortunately hampers variety). However, I have never noticed an enemy using the overview mode – it may very well be a player-exclusive ability. Additionally, there is a new cover mechanic that protects characters from ranged attacks if they are willing to spend a turn going into cover. Leaving cover also costs extra movement points, which means that the cover mechanic is best used very, very sparingly. Perhaps most thrillingly, Blackguards 2 introduces a major evolution in ranged combat design: if you press the “X” key (keys are not rebindable) while giving a move order to an archer, the game displays their potential hit chances from the new position. This is extremely cool. This feature alone makes the game well worth buying for toxophilites and should become a staple in all future turn based games.

As a gift to the fan base, Daedalic has also kept the original game's difficulty-based xp scaling fully intact for Blackguards 2. While I did not perform extensive testing with this mechanic, I tested a short and simple fight that awarded 800 xp in Hard mode, 1000 xp in Normal mode, and 1500 xp in Easy mode. Since the difficulty is perhaps a little on the low side in Hard mode, you may think of Easy difficulty as a sort of “story mode” intended for players in search of a triple-A experience and for reviewers on a second playthrough.

Finally, it is worth considering that mages can now achieve a very healthy amount of mana regeneration (I was generating 7 mana/turn after about ten hours of play), while many useful spells only cost 5 to 10 mana to cast. Consequently, I feel professionally comfortable in stating that pure mage and hybrid gameplay is more varied and powerful than pure melee or archer gameplay in Blackguards 2 – more varied and powerful than it was in the predecessor, in fact.

Battle, Enemy and Map Design

“Varied” is a dangerous word; players may attach certain expectations to it that can unfairly colour the actual gameplay experience. Take, for instance, the new combat mechanics in Blackguards 2. In principle, adding stamina, overview and cover systems and making spells easier to learn and cast increases gameplay variety beyond the already quite satisfying offerings of the first game. And yet there is, perhaps, some room for criticism when it comes to the actual combat experience. Here, too, variety is writ large – while the first game consisted mostly of objectives along the lines of “here is a fixed amount of enemies in a unique configuration, kill them and stay alive to win the map”, the sequel upends all expectations. From the first set of tutorial maps, you will notice that wave combat and unexpected spawn points have become core gameplay mechanics. Spiders drop from ceilings, insects fly in from their secret underground hives, innumerable swarms of footsoldiers spill forth from inconspicuous doorways.

This mode of gameplay has certain advantages; it makes it much easier to create tension when you discover that for every insect you strike down, another one flutters in to take its place (note the variation: this is not merely wave spawning, but replacement spawning), or when a mission gone bad confronts you with three new enemies spilling in every turn. However, those deeply concerned about immersion might find these mechanics to be somewhat upsetting. While the first game usually offered some means of stopping a wave (such as putting stones on top of lice holes), this instalment often leaves it opaque whether enemies will continue to spawn indefinitely, will resurrect instantly or after a few turns, or whether they will simply come in five or six waves that you can confidently mop up bit by bit without having to leave your starting position - if only because a wave of enemies may spawn right in the middle of the group. On the hardest difficulty, making the wrong assumption about how a given map's spawn mechanics work can force you to reload the battle; thus “guess the spawn mechanic” becomes as important an aspect of gameplay as the actual combat itself.

Unfortunately, the flexibility of the spawn systems also somewhat diminishes the newly added ability to position your soldiers before a battle. The areas for placement are often already quite small and constrained, so as not to break the careful balance of the maps. Once you start encountering maps with randomized spawn locations and flying insects dropping straight into your back line, the positioning feature starts to feel rather a bit limited in tactical utility.

It would be unfair to be too critical of the spawn systems, since they bring with them some truly novel challenges. I encountered, for example, a battle against a camp of hunters in the wilderness who kept their captured jungle animals in subterranean holes barred by gates. At the beginning of the fight, the hunters would open the gates and unleash a horde of tigers, monkeys, and toxic killer slugs, who beelined straight for the party (presumably having been tamed by their captors) while the hunters shot poison arrows at me. The holes were deep and dark, disgorging a steady stream of beasts every few turns. There was no way of telling if the animals would spawn indefinitely or not.

Since I was unwilling to risk a full wipe and waste half an hour on an infinite spawn, I chose to quickly rush out to close all the gates, weaving a path through vicious slug beasts while dodging ranged attacks. Sitting back and just killing the oncoming monstrosities from cover could have led to sure-fire failure. Being coaxed into this kind of proactive “move forward or die” gameplay should appeal greatly to those players who are fed up with the relatively “slow and steady” approach found in other modern turn based games like XCOM and Divinity: Original Sin.

In fact, Blackguards 2 nicely facilitates aggressive gameplay by removing all death penalties and auto-healing and resurrecting your group after every battle, even when they are isolated in the middle of a dungeon. In the first game, players were forced into a resource management metagame that required them to sacrifice resources (money, potions, or camping supplies) to regenerate missing hp and mana and cure the “wounds” debuff after battle. The problem with this system was obvious: if you spent all your money, drank all your potions, wasted your camping supplies by resting after every battle, and then had to sell your weapons to be able to afford healing, you might end up in a situation where it was absolutely impossible to progress in the game. As a hardened veteran of German RPGs I never encountered any problems with this system myself, but it is easy to imagine a less conscientious fan from the new world running into severe trouble with this kind of dead end mechanic.

Those fights that do not include constantly re-spawning, resurrecting, or invincible enemies tend to be quite easy; they basically amount to hitting anthropomorphic bags of hit points until they die and you get a victory screen. If you keep your mages on healing duty and use the occasional haste spell to combat the slow entropic force of a half dozen soldiers chipping away at your fighters, you are not likely to have a hard time on any of these “kill all enemies to win” battles. Alternatively, one may make profitable use of the “Cold Shock” spell that deals medium damage to all enemies on the map without a target limit; thus, one can easily eradicate ten or fifteen weak enemies within the first two turns of gameplay. A few times I noticed that enemies would stay in their own area and wait around for my characters to approach; in those cases my mages could simply stay in their starting position, casting Cold Shock and waiting for their mana to regenerate, thereby slowly clearing the entire map of enemy soldiers.

I mention soldiers specifically because they are the dominant type of enemy in the game. This makes fine sense, since Cassia and her group are fighting a professional army, but it does rather limit enemy variety. I would say that about 65 percent of all enemies in BG2 are uniformed swordfighters, spearfighters, and archers of slightly varying power levels, as well as melee insectoids. There are also new magical enemies in the form of sand creatures, bone and wood constructs as well as returning enemy types from the game like spiders, undead, lice, lizard people, etc., though they are all far less prominently featured than the common footsoldier/insect monster.

You will spend quite a lot of your time in combat watching the enemy walk around the battlefield. Many of the battle arenas in Blackguards 2 are really quite a bit larger than they need to be, which can cause some minor tedium issues when combined with the inherent slowness of the turn based movement system. In fact, the designers have specifically created a number of set pieces where your party spawns on one end of the map and the enemies far, far off on the other end, perhaps with one or two hidden traps and a couple of crates or bushes in between. In those cases it is best practice to spam Cold Shock and otherwise skip your party's turns until enemies get into weapon range while the enemy group slowly, carefully, and with measured step advances towards your position. Since there is no way to speed up the enemy animations, you can spend a few minutes out of every battle just watching enemy troops take turns walking around, taking cover, getting out of cover, or taking ultra-long-range pot shots with their bows with a stated hit chance of 0%. Of course, your own animations can feel quite ponderous as well. This is particularly evident on “escape” maps where your party needs to move towards a distant, oh so distant goal past hordes of constantly spawning enemies. My preferred strategy for most of these battles was to manoeuvre a single unit to the finish line while letting the others wait around for the enemies to come and kill them; that way, one may still win the map (all living units escaped, no death penalties) while having to spend less time pointlessly shuffling the whole group across the map. However, this experience could still be smoothed out by adding a “suicide” button to the battle UI.

Battles against archers are also uniquely time intensive, as the camera slowly pans from your group across the map to the archer firing his bow, then follows the arrow flying back towards your group for a couple of seconds, only to see it miss your party member. Then it pans back to the next archer. For those situations it pays to have a piece of stimulating entertainment available on a secondary device. Although the camera movement and various animations only amount to about an hour or two of added playing time (out of 15 hours total), it does feel rather longer when you are in the middle of a heated battle.

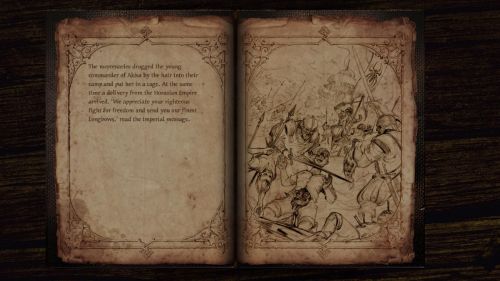

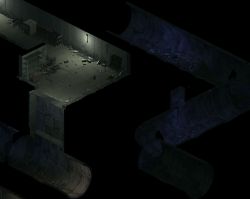

A normal sized map zoomed out to the maximum. Not pictured: enemy archers (left), player archers (right).

The developers have attempted to spruce up the vast expanses that double as battle arenas by furnishing some of the maps with interactive environmental objects like dangling chandeliers or collapsible bridges. However, in practice the effort of manoeuvring enemies into these objects rarely has any noticeable effect on the tide of battle. One particularly problematic environmental mechanic involves the use of strategically placed organs (the musical kind) that are linked to magical circles on the map. Play an organ, and some of the new enemies – like the insect people – are charmed to your side, as long as they are standing in the circle at that time and you've learned the right melody from one of the Creator bosses. Unfortunately, the math is a little shaky for this kind of puzzle; you need to dedicate at least two characters to setting up the trap (one at the instrument, one to lure the enemy into the circle) while spending multiple turns getting into position, which is usually enough time to just smash the enemy to pieces and be done with it. Most problematically, the battles against the bosses who guard the melodies are mid-to-late game content, while most of the puzzle battles can easily be beaten early on; in other words, once you can get the melody, you'll no longer have much use for it. Strangely, the game heavily features these puzzles and even advertises them on the overland map, so they were presumably intended to have some sort of intrinsic value. My advice to Daedalic would be to carefully reduce the amount of references to these organs in the game in future patches, as their advertised presence only serves as a sad reminder of a missed opportunity.

Army management and Conquest

Speaking of opportunities, Blackguards 2 also features an intriguing new addition to the somewhat old-fashioned “fight 100 battles with the same group of people” gameplay of its predecessor; now, you can command your own army! After completing the three hour tutorial, Cassia is gifted a reasonably loyal group of devoted fanatics – swordfighters, spearfighters, and archers – who are basically identical to the enemy army (this makes for suitably subtle political commentary).

You can select two of these mercenaries, drawn from an infinite supply, to accompany your party of four into most battles, though for the really big set pieces (the kind where 25 enemy units all take their turns while you read a good book and enjoy yourself splendidly) you are allowed to bring more. Since they are just nameless peons, the precepts of realistic game design dictate that they may not be even remotely competitive with your main party; consequently, these unnamed followers best serve as meat shields and as occasional ranged support for melee heavy parties.

Your army's general is Faramud, a man of great religious conviction and mediocre skill who only participates in combat when his God decrees it so (one may see another sly piece of political satire here). Far more interesting are the three special recruits you can find throughout the game; a battle mage who drowns enemy armies in fireballs, an assassin who can kill enemy soldiers in a singular strike, and a very large ogre.

These companions can fill the slot of a regular mercenary, which creates a rather interesting shift in difficulty when you unlock them. For instance, the battle mage comes with two high quality mana potions in her inventory, which she dutifully replenishes after every battle. Thus, she is able to put out a tremendous amount of AoE damage by just casting fireballs and chugging potions. Your regular heroes, perpetually wary of spending all their cash on consumables, will not be able to compete with this kind of damage output. This creates a rather interesting battle dynamic where an auto-levelled companion becomes more powerful in combat than the warriors on your core team. At first this kind of balance adjustment might be difficult to adapt to, but it will soon feel exhilarating when you burn down a dozen end game enemies in just two or three turns.

But how do you know what an “end game enemy” is in a game without character levels? This issue was addressed in Blackguards 1 by dividing the game into successive chapters; thus, the developers had tight control over game progression and were able to hand craft their own idiosyncratic difficulty curve in line with their artistic vision. The sequel, however, takes place on an non-linear world map, which poses a major challenge to balancing efforts. How do you maintain challenging gameplay when the player can just avoid difficult battles or grind side quests?

Thankfully, the developers were able to address this issue with verve and panache. Most importantly, they decided to accelerate overall character progression. While a non-magical character in the first game could spend the first 40-50 hours of a hard mode game distributing points between various sensible options – attributes, talents and base stats – a warrior in Blackguards 2 can reach a near-optimal build after about 14 hours due to lower progression costs (in Easy mode, you can get there shortly after the tutorial). Furthermore, character progression is roughly logarithmic: you gain the biggest improvements by investing your first xp in maxing out your main weapon talent or in maxing out mana regen and getting one or two good spells. Since the most drastic changes in character power happen in the early game, and early game freedom is constrained by the extensive tutorial, the actual open world experience is only mildly affected by character progression.

Instead, Daedalic has tied character power closely to equipment. As in the first game, you will find yourself buying most of your equipment from stores, but this time the developer spiced things up with a clever twist. A major benefit of armour is its ability to form “sets”, which, if completed, can confer extremely powerful bonuses, particularly to mana regeneration. During my playthroughs, I found that I could often find most parts of a given set in my army's camp store, but not all of them. Sometimes the missing piece was given out for completing a certain battle, sometimes I had to upgrade the store's inventory before it became available. The converse is also true – sometimes you complete a boss battle, loot an almost complete set from the enemy, but have to keep searching high and low for that darn headpiece before the bonus kicks in. This delicate balance between store bought and looted equipment gives players a sense of profound gratification without having to offer too much powerful loot too early.

In fact, the most concrete benefits from the map battles come in the form of passive boosts - “+10 fire resistance to your footsoldiers”, “equipment upgrade for spear fighters”, “upgraded store inventory”, “unlock the Assassin”, and so forth. All of these bonuses are openly listed on the overworld map, so you can plan your path towards the best bonuses and focus on clearing those areas right from the start.

There is also an “intel” system in place; you can pay exorbitant sums of money to the beggar Riz in exchange for valuable pre-battle information (“this map features a melody puzzle”, “there are footsoldier enemies here”, and so forth). This system could theoretically be gamed by saving, paying for the intel, and then reloading; however, it should be assumed that most gamers would not resort to this kind of fun-killing degenerate gameplay. You can also gather intelligence from prisoners if you select the right interrogation options. This boils down to Riz or one of your companions telling you “this girl is aggressive, but dumb”, and then giving you the option to either threaten her or lie to her. Which option is the correct one? Play Blackguards 2 to find out!

One of the peculiarities of the conquest-based reward system is that it becomes very tempting for so-called “power gamers” to collect all the bonuses before reaching the final battle, even though the narrative goes to great pains to create a sense of terrifying urgency. The developers have addressed this issue by making most of the overworld areas part of the main plot while keeping the side content short and reasonably sweet. The game has 20 overworld areas, each containing one battle arena – though cities and boss lairs can contain two or even three arenas – as well as extra main story fights that trigger at certain points during the game. Of these 20 areas, two are part of the tutorial, one unlocks the final battle, four are the lairs of main quest bosses, and at least four more must be cleared to connect all of them. That leaves a quite respectable, but by no means overwhelming nine extra battle areas, plus about 5-6 short side battles as optional parts of the gameplay experience, clocking in at two to three hours total of optional combat fun. Furthermore, the developers have managed to improbably extend the game's length even further, much like a favourite piece of chewing gum, by featuring enemy counter attacks on already conquered territory that occur after every three map battles. Unless your heroes are already present in the same area, you will have to fight these battles with “guards”. This amounts to a horde of footsoldiers fighting another horde of footsoldiers on a previously used map with an extra option to put down a few traps before battle. Turns can take a long time in these battles, and no xp or loot reward of any kind is offered.

The game's detractors have made great sport of the fact that the scope of the optional content in BG2 does not come close to the amount and variety of side quests in even just the third chapter of the original Blackguards. However, this decreased focus on optional content has given Daedalic more time to work on the most complex features of the core game; specifically, on the boss fights and the AI, as well as on the core cast of characters and the story itself.

Bosses and AI

In Blackguards 2, you will be fighting five major bosses, as well as a number of less dangerous named enemies. Four of the major bosses are spell casters – the so-called “creators”, who command magical creatures. Since the game's combat system heavily favours mages, it seems eminently sensible that the bosses would also wield magic. However, in a peculiar, audacious, intriguingly puzzling twist on standard game design, the main challenge in these battles does not derive from the spell casting or even from the boss enemies themselves.

I will briefly describe the most complex boss battle of the game, with changed monster and character names so as not to spoil more content than necessary.

In one battle, your core party – no followers are allowed into boss battles – is dumped into a small corridors with six gates branching out. Two levers are presented at one end of the corridor, protected by the boss Brunhilde and her giant louse pet. You need to reach the levers to continue; however, the louse blocks the entire corridor, has a large radius knockdown sweep, can take heroes out of combat temporarily, deals high ranged damage, heals itself every turn and resurrects if killed. Meanwhile, the mage goes through a fixed rotation of buff spells, casting a damage field at the center of the corridor, and occasionally enraging a hero. If a hero approaches her, she may launch into a vicious melee attack with her staff that can easily kill the character within a few turns. She also automatically heals every turn. The first challenge of the map lies in getting a hero past the louse in order to pull the levers, not trigger the mage's melee attack, and stay alive long enough for the other heroes to complete a puzzle behind the corridor gates that only works if they have certain types of weapons equipped and are not enraged by the mage at an inopportune moment. Then, after 15-20 minutes of gameplay, Brunhilde will enter her final phase, Dragonball style, and there will be another fight altogether.

If you have the wrong weapon composition, you need to replay both this battle and the previous one to re-equip; if you do not have enough healing, cannot kill the louse quickly enough or lure it out of position fast enough to last through the puzzle, or cannot kill SuperBrunhilde, you need to lower the difficulty or go someplace else.

The other boss battles are generally much simpler. All the boss battles are built around footsoldiers, pets, and secondary enemies as the primary obstacles on the way to the next lever or death pit while the enemy mages tend to devote themselves to buffing and/or a short damage phase. A certain penchant for guarded levers and invulnerable bosses is also in evidence. Loot for all bosses generally consisted of minor artefacts and incomplete armor sets.

Only Brunhilde stood out as a more involved battle that offered a complex challenge and required a well-planned strategy and a well-rounded party to take on – which was perhaps rather unfair, given how the rest of the game was designed. Indeed, there has been a tremendous outcry of disapproval from the fanbase about that particular fight, and Brunhilde and her pet have already been adjusted to more manageable levels.

Fans of Baldur's Gate 2 and its mage battles may idiotically have hoped for similarly complex gameplay from its acronymsake. However, there is a very good reason why Blackguards 2 instead focuses on its strengths of wave spawn, invulnerability and resurrection mechanics. To put it bluntly, BG2's AI (“KI” in German) gives the impression of having been very carefully designed to command large hordes of hastily trained footsoldiers possessed of thoroughly unexceptional intellect. This is the kind of soldier who sees three of his comrades step into a spiked wooden board trap in a wide open hallway and die in painful agony, then steps right into the same square; the kind of soldier who skips their turn while standing inside a burning bush.

However, putting this same AI in charge of a reasonably clear thinking character who has eight or nine distinct and powerful options in any given combat round – like a properly built mage – would constitute a grievous misuse of its specialized abilities. Thus, the bosses in Blackguards 2 rely on what a poster claiming to be Daedalic producer Johannes Kiel while deriving no imaginable benefit from said claim has called “different AIs [...] that are supposed to reflect their personalities.“ Since these bosses are, in their heart of hearts, fairly simple folk who only get two or three short conversations throughout the game (taunt the hero maniacally / negotiate conditions after defeat), it logically follows that they would also exhibit fairly simple behaviour and only cast one or two spells during combat. As an extreme example, one of the most arrogant and incompetent bosses in the game entered combat, gazed in silent contemplation at his assembled followers for a turn or two, and then jogged slowly towards the only thing that could properly defeat him, thereby taking himself out of commission without the party laying a single finger on him. There is a certain poetic beauty to this kind of AI scripting.

This conscious focus on character based gameplay marks a clear departure from the relatively thin gruel of Blackguards 1, whose central ludonarrative conceit of an audience-friendly “Taugenichts” hero (a German term referring to a person of limited vim and ability) stood at odds with the kind of challenging, nail-biter tactical gameplay usually only featured in chess and high-stakes poker. Here, too, Blackguards 2 forges new paths.

A Story of Choices and Consequences

Cassia, a noblewoman possessed of great beauty and intellect, has been unjustly imprisoned by the malicious Marwan, who has crowned himself ruler of the corrupt city of Mengbilla. Thus begins an epic story of madness, betrayal, and either revenge or greed or nihilism or more madness, depending on player choice, culminating in a final confrontation that will leave mature gamers of all ages glued to their keyboards. Thus the game's central conceit.

This kind of story deserves a grand stage, and the pre-release coverage has not been shy to point out the tremendous honour afforded to the Daedalic writing team: the story of Blackguards 2 is part of the official The Dark Eye canon.

Of course, Daedalic giveth and Daedalic taketh away; thus, what the erudite gamer gains in terms of epic, nuanced, action-packed storytelling is somewhat diminished by the fact that this story and its conclusion still had to be distilled into some sort of official version fit for printing on a very expensive piece of paper. The developers are surely familiar with the rather immersion-breaking solutions that BioWare had found for their own licenced game Knights of the Old Republic, but Daedalic have chosen a different path.

While keeping this review as spoiler free as possible, I will say only this much: the world of The Dark Eye is ruled by Gods, powerful beings who control the destinies of us all. Can a mere mortal, a mere gamer, really hope to contend with such forces? The Gods will steer our stories to the conclusion that pleases them; such is the nature of Fate.

With this detail cleared up, permit me to stress the intricate ways in which the other, less cosmically relevant characters can be manipulated and moulded. It is no accident that the core party of BG2 simply sees Cassia thrown together with the male element of Blackguards 1: Naurim, Zurbaran, and Takate. These are three guys nobody – and certainly not the canon – really gives a toss about, and manipulating their lives is one of the truest joys of playing this game. You can appeal to their basest desires, learn their darkest secrets, make them fall in pure and noble love with a not conventionally attractive serial poisoner, amplify their suicidal tendencies to your supreme advantage, and just plain kill the pigs once you are done with them. This is all good and proper.

It helps that Naurim et al. are generally more loathsome and pathetic than in the first game, so the choice to treat them well provides a certain amount of challenge in and of itself. To sweeten the deal, the developer has implemented a rudimentary loyalty system, similar to the approval system from Dragon Age: Origins. Make Naurim angry in conversation (not very difficult) and he gets “Naurim's Wrath 1/3” which increases his endurance (though it is currently bugged and does nothing). Make him angry a few more times, and he finally gets the capstone bonus “Naurim's Wrath 3/3”, a mighty boon that possibly increases his resistance to knockdown effects by an unspecified amount (knockdown resistance is not currently explained or shown anywhere on the UI). Be friendly to him, and he gets another bonus entirely. These are choices with consequences.

Between the canonical story and Cassia's intricate manipulations of her gutter trash companions, there exists a delicate middle ground. What kind of person is Cassia? What does she want from life? Why does she want it? Here is where the game really shines, presenting an evolution of the classic Light Side-Dark Side system modernized for a 21st century audience. During her lengthy imprisonment (which in a fine bit of meta commentary, also doubles as a tutorial) she comes across the book “The Good Ruler”, which is possibly inspired by Machiavelli's Il Principe. The book not only serves as Cassia's trainer for spells, weapon skills, trapping, mana regeneration, her ability to endure physical pain, and so forth, but it also contains a crucial passage that informs her entire world view. The good ruler, it reads, rules either by love or by fear. “If you cannot rule by love, rule by fear. Love is the stronger bond, but fear is quicker.”

Thus, in a gentle, unobtrusive way, the game lays bare the central choice-and-consequence dynamic of the game. Cassia decides that she wants to rule. She will break out of prison, depose the fiendish Marwan – with whatever motivation the player chooses to give her – and then she will sit on Mengbilla's Shark Throne. Will she be a Loved ruler or a Feared one? You, the player, decide.

The various ways to shift your position on the Loved-Feared spectrum (helpfully given voice by the beggar Riz, who tells you “You are loved” or “They think you're a monster.” based on what you choose to do) emerge during gameplay. Once Cassia has raised her army of murderous maniacs, she directs them to conquer the region. When she takes a city, she can decide to have her legion kill the last stragglers – that makes her Feared and causes people to say uncouth things about her, but gives cash and xp. Alternatively, she can wait until she captures a handmaiden or a slave, and then decide to let them go. That makes her Loved, and may unlock a later dialogue in which the spared party returns to tell her that they are most grateful. Then she can go back, raze the city, and avoid being Feared because her Loved points cancel it out. She may also be given the opportunity to brutally torture someone, or to simply ask them nicely. Either choice will affect her Loved-Feared rating, which is communicated by means of a soft “ding” sound. The sound for gaining Fear points is the same as for Love points, so players will have closely analyse the dialogue options in order to determine which kind of points each option grants. If these choices seem opaque and hard to predict to you, worry not; the end game offers a (very realistically presented) way of changing your rating in case you screw up.

If you find these Telltale-esque charms less compelling than the promise of a simple, well-told story with fine voice actors, then I can give you a strong, unequivocal, no-nonsense recommendation for Blackguards 2. The German voice acting in particular is very, very good, particularly with the cultist Faramud chewing on his lines like the mentally unhinged antagonist in a Brechtian radio play. Cassia's voice actress also does a fine job portraying a woman unsure of her own sanity. Early in the tutorial, Cassia is bitten by a spider whose bite causes “madness or death”, and it is to her actress's great credit that she can maintain any sense of ambiguity in the matter at all.

BG2 also features a narrator, a suitably gruff, foreboding fellow who introduces and concludes almost every single battle with a short piece of commentary.

By contrast, the English voice actors provide the usual coarse inflections and stumbling rhythms that are inimical to the language. The script still makes the experience reasonably tolerable, but if Blackguards 2 offered the option to play with English text and German speech, I would strongly recommend it to all prospective foreign players. Hopefully an official patch will be provided to fix this issue.

Beyond the story of crazy Cassia and her curious Love-Fear barometer, the erudite player will also encounter a number of intriguing subplots and thematic connections. The companions all have some sort of family issue, the men around Cassia tend to underestimate her on account of her mad behaviour, and the villainous Marwan himself has a potentially interesting back story with our heroine that speaks to issues of gender politics and intimate relationships. Unfortunately, these angles are only explored superficially – often extremely superficially. Of course, the idea that a video game would, or, god forbid, should have anything useful to say about real world issues is completely ludicrous on its face; still, since the game does make an earnest effort to introduce these themes, it seems fair game to point out its inevitable shortcomings in this area.

Ultimately, I found it rather difficult to escape the unfortunate impression of squandered narrative potential. This was not aided by the fact that Blackguards 2 only has a truncated epilogue. You can choose between two minutely different outcomes for Cassia's story (on the Mass Effect 3 scale, they would be roughly equivalent to a carmine and a burgundy ending), but the hardcore choice and consequentialists who want to see ending slides or hard consequences to their early game actions will find no succour here. You can make dubious deals and tough decisions that look and feel like they should have dire long term consequences, but that are never again mentioned in the game at all. More esoteric features like stat-based dialogue choices or any acknowledgement of Cassia being a magic user are also absent. But is that kind of narrative responsiveness really something one should reasonably expect from a 15-hour budget game produced in less than a year? Not all video game narratives can be as grand as Game of Thrones, and not all heroines need to be as complex and emotionally resonant as Daenerys Targaryen; sometimes, a well-acted dialogue and a short ending cutscene are all it takes to bring a game to its natural conclusion.

Recommendation

Playing Blackguards 2 after Blackguards 1 is remarkably similar to the experience of playing Dragon Age 2 after Dragon Age: Origins. Some players will prefer the first game for its sheer volume and “old school” flair, while others will be drawn to its sleeker, more assured successor. Some will appreciate BG2's greater focus on storytelling, its unique depiction of mental illness, the tightly progressing story suffused with a malodorous air of inevitability, the greater emphasis on companion interactions, the deft use of negative space in map design as well as in character development, and the tight focus on high-density, high-volume wave combat.

Others will protest “Oh, but Blackguards 1 had heart! If it sang the Jazz, Louis Armstrong would be blowing its trumpet. Blackguards 2 lacks that “je ne sais quoi” (or “Ich weiß nicht was”) that makes a solid game fun! And it wasn't so bloody tedious with the five minute enemy turns and the endless respawns and so forth. I honestly didn't mind having a complex character creation system! Why couldn't they just make a better Blackguards 1?” I know that many readers will identify with these statements, and their points are, of course, no less valid.

In the end, the independently minded reader is free to make his or her own decision on the nature of the game based on the objective facts presented in this review. If you still feel utterly lost and confused, I would recommend starting with the cheaper, meatier Blackguards 1 and seeing where that takes you.

In recent years, Daedalic Entertainment, based in Europe's cultural capital of Hamburg, Germany, has applied this work ethic to the adventure genre. Today, Daedalic are virtually the only remaining major developer of complex and well-written adventure games. Imagine, then, what such a team of professionals, masters in marrying complex gameplay to transcendent storytelling, could achieve in the exalted sphere of role play gaming. After years of public exhortations, Daedalic finally made their first cautious entry into the RPG genre in early 2014. Blackguards was a well-received sleeper hit that offered players an intriguing combination of tactical turn based combat with a harrowing story of death, betrayal, and heroism, built on the foundation of the German “The Dark Eye” setting (in essence, a subtly tweaked and expanded version of the American “Dungeons and Dragons” system).

Blackguards was not a perfect game: its provocatively challenging gameplay proved a turn-off to those who found no joy in complexity, while the game's laser-like focus on a simple, linear, yet wholly sufficient central narrative served to alienate dedicated explorers, romantic souls, and compulsive collector types alike. Blackguards's strengths, however, were in areas that had long since lain fallow in modern RPGaming: it offered a remarkable amount of freedom in character creation and development that put any party based game since the Realms of Arkania trilogy to shame. While the game consisted almost entirely of combat (and at least 40 hours worth of combat at that), the designers did their utmost to make every encounter unique, challenging, and – in my purely subjective opinion – quite simply interesting to play through. The standards that Blackguards has set in encounter design will very likely remain an industry benchmark for generations to come.

Now, less than one year later, Daedalic has released Blackguards 2. Their design approach was different this time around. Almost every aspect of the gameplay has undergone a radical change; generally speaking, these changes involved cutting out the most daunting and complex gameplay mechanics, and replacing them with simpler, more accessible substitutes.

Let us start with the areas where the changes are most obvious:

Character Creation and Development

In the first Blackguards, a character's base attributes directly influenced every aspect of their combat performance. A warrior with high Strength hit for more damage, even with weapons he had little training in; a mage with high Constitution had a better chance of resisting wound debuffs and status effects. Success rolls for spell casters also checked attributes; a spell that emphasized physical effects may have rolled against the caster's Strength, while an illusion spell may have checked their Charisma. Finally, passive perks and new combat moves were only unlocked for purchase based on hard attribute requirements.

The spell system added a further intricacy by attaching different xp costs to improving different spells, based on the spell's power. Burst of Flame – mostly a single target spell – was cheaper to improve than the large AoE spell Fireball. In a game with no xp grinding opportunities, this mechanic encouraged you to gauge whether the more powerful spells were indeed worth the investment, or whether you would be better off diversifying your tactical portfolio by investing in multiple cheaper spells. This was especially important since spells could fail; trying to cast a spell that checked attributes your mage had neglected (like Strength) required you to make a substantial xp investment in the spell just to achieve a 60 or 70% success rate. Since even a spell with a 70% success rate could potentially fail hundreds of times in a row, this system could occasionally be extremely frustrating; still, it worked well enough in the absence of better alternatives.

One particular wrinkle of the system was that attributes could be directly increased with xp, just like talents and spells; thus, you might get into a situation in which increasing your Intelligence improved a mage's prowess with Intelligence-based spells more than directly investing xp in those spells would have done, while also unlocking further perks. Simply put, the character system rewarded careful and methodical thinking. Conversely, distributing your xp without much thought could make for an immensely joyless gameplay experience.

Blackguards 2 scuttles all of these mechanics with an admirable clarity of purpose. Attributes have been removed. All spells cost an equal amount of xp, though they are by no means equally useful. Most Spells cannot fail at all. Meanwhile, weapons have a higher base to-hit chance even at low talent values and are also easier to master, since increasing a weapon talent now automatically grants the damage bonus – along with other perks – that used to be tied to strength and other attributes. Blackguards 2 is simpler, sleeker, slimmer than its predecessor; it is a mellow sort of game.

Simplicity, though much maligned in hardcore circles, is by no means a bad thing in and of itself – it helps games attract a broader demographic, reduces the potential for frustration, and can provide young gamers with a safe space to learn the basics of turn-based gameplay in a fun and entertaining manner. Moreover, simplifying complex mechanics can make a game much easier to balance. The first Blackguards had so many moving parts and interdependencies that some simplification in the service of creating a more balanced game might have been a very fine idea indeed.

Blackguards 2 is not, objectively speaking, more balanced than its predecessor. One paradigmatic example of BG2's various minor imbalances is the handling of magic-capable PCs. In the first game, the player was presented with a choice of whether his new character would be able to cast spells or not. A non-magic capable character would never be able to cast a single spell, but they had more xp to spend on physical talents and could wear heavy armour without penalties. A pure mage would have more burst damage power, but could run out of mana quickly, was weakly armoured, and had limited long-term damage potential. A hybrid character combining magic and some weapon talents could potentially be stronger than either of the pure options, but was more difficult to build due to relying on many different attributes and suffering harsh spellcasting penalties in iron armour.

In Blackguards 2, the main character Cassia starts as a magic-capable character with no xp penalty. Iron armour penalties only reduce the size of a character's mana pool and their mana regeneration (there is no spell failure after all) and can be completely removed by buying two perks that together cost less than mastering a single spell. If one chooses not to take these perks, one will still have enough mana to cast a buff spell or two per battle. There is also another perk that gives you extra armor if you have learned three spells. It is easy to see the value behind these changes: mages were more interesting to build in the first game, and playing interesting games is fun. Ergo, every player character can learn magic in the second game. And since every PC can cast spells, penalties for spell casters should be reduced, so that casting spells is fun even for people who prefer to play fighters. The logic is sound.

Have pure physical fighters been buffed to compensate for these changes? No. Instead, Blackguards 2 introduces a new stamina mechanic that functions exactly like mana (this seems a misstep, since it actually makes the game more complex) and limits the amount of special attacks a warrior can perform per battle. Special attack spam was the core gameplay mechanic for physical fighters in the first game, mainly balanced by the fact that the specials could decrease your hit chance against high-defense targets so far that using standard attacks or changing targets was occasionally preferable. Now, with the generally increased hit chance, this would no longer have been a viable balancing strategy; thus, Daedalic employs the stamina mechanic to introduce variety in gameplay.

A new character has 40 stamina, and 1 stamina regeneration per turn; the most useful special attacks cost at least 10 stamina. In practice, this means that physical fighters spend a lot of time auto attacking while waiting for their stamina to regenerate. It is up to the individual player to decide whether spamming auto attacks is superior to spamming special attacks, and I will pass no judgement on this matter.

The biggest positive change for warriors has been a much-requested fix to weapon damage; while the first game rolled “virtual dice” and left frustrated players burning their virtual game boxes after getting multiple bad rolls in a row, Blackguards 2 simply offers up a single number of sublime simplicity – you always hit for the same amount before damage resistances. No fuss, no mess, easy come, easy go.

On that note, the armour system has been changed from the flat absorption + percentage reduction hybrid system of the first game to purely percentage based resistances. This has served to make the armour mechanics much more accessible for neophyte players, who notoriously had to rely on a fan written manual to make even the slightest amount of sense of the Blackguards 1 system. Daedalic has further reduced any chance of confusion by including a sleek new stat summary on the inventory screen that immediately shows you character resistances, regeneration, and weapon damage. It is the most obvious change to the game's UI, and it is a very good one.

Archers, meanwhile, now have an ambush/overview mechanic that elevates their gameplay options almost to the level of a gun fighter in Shadowrun Returns (though the stamina mechanic unfortunately hampers variety). However, I have never noticed an enemy using the overview mode – it may very well be a player-exclusive ability. Additionally, there is a new cover mechanic that protects characters from ranged attacks if they are willing to spend a turn going into cover. Leaving cover also costs extra movement points, which means that the cover mechanic is best used very, very sparingly. Perhaps most thrillingly, Blackguards 2 introduces a major evolution in ranged combat design: if you press the “X” key (keys are not rebindable) while giving a move order to an archer, the game displays their potential hit chances from the new position. This is extremely cool. This feature alone makes the game well worth buying for toxophilites and should become a staple in all future turn based games.

As a gift to the fan base, Daedalic has also kept the original game's difficulty-based xp scaling fully intact for Blackguards 2. While I did not perform extensive testing with this mechanic, I tested a short and simple fight that awarded 800 xp in Hard mode, 1000 xp in Normal mode, and 1500 xp in Easy mode. Since the difficulty is perhaps a little on the low side in Hard mode, you may think of Easy difficulty as a sort of “story mode” intended for players in search of a triple-A experience and for reviewers on a second playthrough.

Finally, it is worth considering that mages can now achieve a very healthy amount of mana regeneration (I was generating 7 mana/turn after about ten hours of play), while many useful spells only cost 5 to 10 mana to cast. Consequently, I feel professionally comfortable in stating that pure mage and hybrid gameplay is more varied and powerful than pure melee or archer gameplay in Blackguards 2 – more varied and powerful than it was in the predecessor, in fact.

Battle, Enemy and Map Design

“Varied” is a dangerous word; players may attach certain expectations to it that can unfairly colour the actual gameplay experience. Take, for instance, the new combat mechanics in Blackguards 2. In principle, adding stamina, overview and cover systems and making spells easier to learn and cast increases gameplay variety beyond the already quite satisfying offerings of the first game. And yet there is, perhaps, some room for criticism when it comes to the actual combat experience. Here, too, variety is writ large – while the first game consisted mostly of objectives along the lines of “here is a fixed amount of enemies in a unique configuration, kill them and stay alive to win the map”, the sequel upends all expectations. From the first set of tutorial maps, you will notice that wave combat and unexpected spawn points have become core gameplay mechanics. Spiders drop from ceilings, insects fly in from their secret underground hives, innumerable swarms of footsoldiers spill forth from inconspicuous doorways.

This mode of gameplay has certain advantages; it makes it much easier to create tension when you discover that for every insect you strike down, another one flutters in to take its place (note the variation: this is not merely wave spawning, but replacement spawning), or when a mission gone bad confronts you with three new enemies spilling in every turn. However, those deeply concerned about immersion might find these mechanics to be somewhat upsetting. While the first game usually offered some means of stopping a wave (such as putting stones on top of lice holes), this instalment often leaves it opaque whether enemies will continue to spawn indefinitely, will resurrect instantly or after a few turns, or whether they will simply come in five or six waves that you can confidently mop up bit by bit without having to leave your starting position - if only because a wave of enemies may spawn right in the middle of the group. On the hardest difficulty, making the wrong assumption about how a given map's spawn mechanics work can force you to reload the battle; thus “guess the spawn mechanic” becomes as important an aspect of gameplay as the actual combat itself.

Unfortunately, the flexibility of the spawn systems also somewhat diminishes the newly added ability to position your soldiers before a battle. The areas for placement are often already quite small and constrained, so as not to break the careful balance of the maps. Once you start encountering maps with randomized spawn locations and flying insects dropping straight into your back line, the positioning feature starts to feel rather a bit limited in tactical utility.

It would be unfair to be too critical of the spawn systems, since they bring with them some truly novel challenges. I encountered, for example, a battle against a camp of hunters in the wilderness who kept their captured jungle animals in subterranean holes barred by gates. At the beginning of the fight, the hunters would open the gates and unleash a horde of tigers, monkeys, and toxic killer slugs, who beelined straight for the party (presumably having been tamed by their captors) while the hunters shot poison arrows at me. The holes were deep and dark, disgorging a steady stream of beasts every few turns. There was no way of telling if the animals would spawn indefinitely or not.

Since I was unwilling to risk a full wipe and waste half an hour on an infinite spawn, I chose to quickly rush out to close all the gates, weaving a path through vicious slug beasts while dodging ranged attacks. Sitting back and just killing the oncoming monstrosities from cover could have led to sure-fire failure. Being coaxed into this kind of proactive “move forward or die” gameplay should appeal greatly to those players who are fed up with the relatively “slow and steady” approach found in other modern turn based games like XCOM and Divinity: Original Sin.

In fact, Blackguards 2 nicely facilitates aggressive gameplay by removing all death penalties and auto-healing and resurrecting your group after every battle, even when they are isolated in the middle of a dungeon. In the first game, players were forced into a resource management metagame that required them to sacrifice resources (money, potions, or camping supplies) to regenerate missing hp and mana and cure the “wounds” debuff after battle. The problem with this system was obvious: if you spent all your money, drank all your potions, wasted your camping supplies by resting after every battle, and then had to sell your weapons to be able to afford healing, you might end up in a situation where it was absolutely impossible to progress in the game. As a hardened veteran of German RPGs I never encountered any problems with this system myself, but it is easy to imagine a less conscientious fan from the new world running into severe trouble with this kind of dead end mechanic.

Those fights that do not include constantly re-spawning, resurrecting, or invincible enemies tend to be quite easy; they basically amount to hitting anthropomorphic bags of hit points until they die and you get a victory screen. If you keep your mages on healing duty and use the occasional haste spell to combat the slow entropic force of a half dozen soldiers chipping away at your fighters, you are not likely to have a hard time on any of these “kill all enemies to win” battles. Alternatively, one may make profitable use of the “Cold Shock” spell that deals medium damage to all enemies on the map without a target limit; thus, one can easily eradicate ten or fifteen weak enemies within the first two turns of gameplay. A few times I noticed that enemies would stay in their own area and wait around for my characters to approach; in those cases my mages could simply stay in their starting position, casting Cold Shock and waiting for their mana to regenerate, thereby slowly clearing the entire map of enemy soldiers.

I mention soldiers specifically because they are the dominant type of enemy in the game. This makes fine sense, since Cassia and her group are fighting a professional army, but it does rather limit enemy variety. I would say that about 65 percent of all enemies in BG2 are uniformed swordfighters, spearfighters, and archers of slightly varying power levels, as well as melee insectoids. There are also new magical enemies in the form of sand creatures, bone and wood constructs as well as returning enemy types from the game like spiders, undead, lice, lizard people, etc., though they are all far less prominently featured than the common footsoldier/insect monster.

You will spend quite a lot of your time in combat watching the enemy walk around the battlefield. Many of the battle arenas in Blackguards 2 are really quite a bit larger than they need to be, which can cause some minor tedium issues when combined with the inherent slowness of the turn based movement system. In fact, the designers have specifically created a number of set pieces where your party spawns on one end of the map and the enemies far, far off on the other end, perhaps with one or two hidden traps and a couple of crates or bushes in between. In those cases it is best practice to spam Cold Shock and otherwise skip your party's turns until enemies get into weapon range while the enemy group slowly, carefully, and with measured step advances towards your position. Since there is no way to speed up the enemy animations, you can spend a few minutes out of every battle just watching enemy troops take turns walking around, taking cover, getting out of cover, or taking ultra-long-range pot shots with their bows with a stated hit chance of 0%. Of course, your own animations can feel quite ponderous as well. This is particularly evident on “escape” maps where your party needs to move towards a distant, oh so distant goal past hordes of constantly spawning enemies. My preferred strategy for most of these battles was to manoeuvre a single unit to the finish line while letting the others wait around for the enemies to come and kill them; that way, one may still win the map (all living units escaped, no death penalties) while having to spend less time pointlessly shuffling the whole group across the map. However, this experience could still be smoothed out by adding a “suicide” button to the battle UI.

Battles against archers are also uniquely time intensive, as the camera slowly pans from your group across the map to the archer firing his bow, then follows the arrow flying back towards your group for a couple of seconds, only to see it miss your party member. Then it pans back to the next archer. For those situations it pays to have a piece of stimulating entertainment available on a secondary device. Although the camera movement and various animations only amount to about an hour or two of added playing time (out of 15 hours total), it does feel rather longer when you are in the middle of a heated battle.

A normal sized map zoomed out to the maximum. Not pictured: enemy archers (left), player archers (right).

The developers have attempted to spruce up the vast expanses that double as battle arenas by furnishing some of the maps with interactive environmental objects like dangling chandeliers or collapsible bridges. However, in practice the effort of manoeuvring enemies into these objects rarely has any noticeable effect on the tide of battle. One particularly problematic environmental mechanic involves the use of strategically placed organs (the musical kind) that are linked to magical circles on the map. Play an organ, and some of the new enemies – like the insect people – are charmed to your side, as long as they are standing in the circle at that time and you've learned the right melody from one of the Creator bosses. Unfortunately, the math is a little shaky for this kind of puzzle; you need to dedicate at least two characters to setting up the trap (one at the instrument, one to lure the enemy into the circle) while spending multiple turns getting into position, which is usually enough time to just smash the enemy to pieces and be done with it. Most problematically, the battles against the bosses who guard the melodies are mid-to-late game content, while most of the puzzle battles can easily be beaten early on; in other words, once you can get the melody, you'll no longer have much use for it. Strangely, the game heavily features these puzzles and even advertises them on the overland map, so they were presumably intended to have some sort of intrinsic value. My advice to Daedalic would be to carefully reduce the amount of references to these organs in the game in future patches, as their advertised presence only serves as a sad reminder of a missed opportunity.

Army management and Conquest

Speaking of opportunities, Blackguards 2 also features an intriguing new addition to the somewhat old-fashioned “fight 100 battles with the same group of people” gameplay of its predecessor; now, you can command your own army! After completing the three hour tutorial, Cassia is gifted a reasonably loyal group of devoted fanatics – swordfighters, spearfighters, and archers – who are basically identical to the enemy army (this makes for suitably subtle political commentary).

You can select two of these mercenaries, drawn from an infinite supply, to accompany your party of four into most battles, though for the really big set pieces (the kind where 25 enemy units all take their turns while you read a good book and enjoy yourself splendidly) you are allowed to bring more. Since they are just nameless peons, the precepts of realistic game design dictate that they may not be even remotely competitive with your main party; consequently, these unnamed followers best serve as meat shields and as occasional ranged support for melee heavy parties.

Your army's general is Faramud, a man of great religious conviction and mediocre skill who only participates in combat when his God decrees it so (one may see another sly piece of political satire here). Far more interesting are the three special recruits you can find throughout the game; a battle mage who drowns enemy armies in fireballs, an assassin who can kill enemy soldiers in a singular strike, and a very large ogre.

These companions can fill the slot of a regular mercenary, which creates a rather interesting shift in difficulty when you unlock them. For instance, the battle mage comes with two high quality mana potions in her inventory, which she dutifully replenishes after every battle. Thus, she is able to put out a tremendous amount of AoE damage by just casting fireballs and chugging potions. Your regular heroes, perpetually wary of spending all their cash on consumables, will not be able to compete with this kind of damage output. This creates a rather interesting battle dynamic where an auto-levelled companion becomes more powerful in combat than the warriors on your core team. At first this kind of balance adjustment might be difficult to adapt to, but it will soon feel exhilarating when you burn down a dozen end game enemies in just two or three turns.

But how do you know what an “end game enemy” is in a game without character levels? This issue was addressed in Blackguards 1 by dividing the game into successive chapters; thus, the developers had tight control over game progression and were able to hand craft their own idiosyncratic difficulty curve in line with their artistic vision. The sequel, however, takes place on an non-linear world map, which poses a major challenge to balancing efforts. How do you maintain challenging gameplay when the player can just avoid difficult battles or grind side quests?

Thankfully, the developers were able to address this issue with verve and panache. Most importantly, they decided to accelerate overall character progression. While a non-magical character in the first game could spend the first 40-50 hours of a hard mode game distributing points between various sensible options – attributes, talents and base stats – a warrior in Blackguards 2 can reach a near-optimal build after about 14 hours due to lower progression costs (in Easy mode, you can get there shortly after the tutorial). Furthermore, character progression is roughly logarithmic: you gain the biggest improvements by investing your first xp in maxing out your main weapon talent or in maxing out mana regen and getting one or two good spells. Since the most drastic changes in character power happen in the early game, and early game freedom is constrained by the extensive tutorial, the actual open world experience is only mildly affected by character progression.