RPG Codex Retrospective Review: The Elder Scrolls: Arena (1994)

RPG Codex Retrospective Review: The Elder Scrolls: Arena (1994)

Review - posted by Crooked Bee on Wed 13 May 2015, 15:06:44

Tags: Bethesda Softworks; The Elder Scrolls: ArenaOnce upon a time, in a land far, far away from Australia, there was a good company called Bethesda Softworks. During that fabled time, Bethesda used to release computer role-playing games, mostly open world (like their masterpieces Daggerfall and Morrowind) but also dungeon-crawling (like the underappreciated Battlespire). Unfortunately, the company went (creatively) bankrupt just after the release of the last Elder Scrolls game, Morrowind, in 2002, and all that remains of it now is the name.

It wasn't the 1996 Daggerfall that started the Elder Scrolls series' rise to fame, though. It was the simpler, half-forgotten The Elder Scrolls: Arena from 1994. In this look back at the often neglected title, esteemed community member Deuce Traveler tells you why Arena can, despite its shortcomings, be worth playing today - and how the experience of playing it differs from its less than stellar reputation. Have a snippet:

Read the full article (with pictures!): RPG Codex Retrospective Review: The Elder Scrolls: Arena (1994)

It wasn't the 1996 Daggerfall that started the Elder Scrolls series' rise to fame, though. It was the simpler, half-forgotten The Elder Scrolls: Arena from 1994. In this look back at the often neglected title, esteemed community member Deuce Traveler tells you why Arena can, despite its shortcomings, be worth playing today - and how the experience of playing it differs from its less than stellar reputation. Have a snippet:

I had originally never intended to play The Elder Scrolls: Arena, as I'd heard enough about this imperfect creation from other RPG fans to keep me away from it. It was said that the game is unbalanced. That it feels incomplete. That its main quest and characters are shallow when compared with that of contemporary RPGs such as the Ultima games or Betrayal at Krondor. But in the end, I decided to give the game a go as part of a larger project I am working on, in order to ascertain these facts for myself. What I found was a game that is indeed quite unbalanced, with many gameplay elements that feel rushed and incomplete, and a main story arc filled with cliche fantasy tropes. And yet, the game was a total joy to play, like a B-movie that manages to be greater than the sum of its faults.

[...] Arena's main quest dungeons are surprisingly evocative. Certainly not the initial dungeon, which is a simple exercise in hacking and slashing, but the game's later dungeons are scattered with clues, which deliver deeper lore and all sorts of tales of tragedy. These tales speak of better times and ancient kingdoms felled long ago through wars and betrayals. For example, one memorable moment takes place upon entering an early dungeon, an abandoned keep where you find a sign forbidding violence and promoting peace within, followed by bloodstains and skeletal remains on the floor further down the hall. Deeper inside, you find messages suggesting that the last defenders of the keep were retreating further in hopes of finding safety. You find no further messages by them, a grim reminder that Tamriel is quite the dangerous world despite the power of the Imperial government.

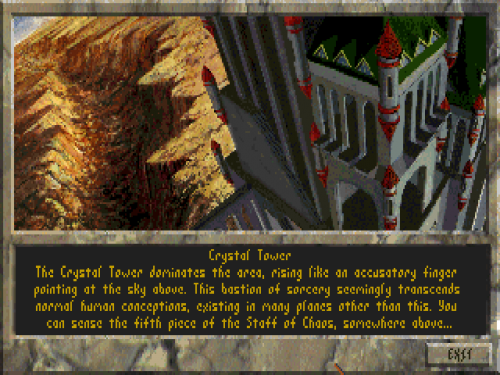

The main quest dungeons are also fairly diverse in terms of aesthetic presentations. There's the initial dungeon which looks like a cross between a prison and a sewer, dungeons which take place in fallen and decrepit keeps, towers, outdoor gardens, and the game's final dungeon which starts in a palace. As the game progresses, your enemies change and become more difficult, though the last third becomes a bit repetitious through overuse of the same difficult monsters. Exploration is rewarded, with randomly generated treasure laying in hidden vaults off the direct paths. Sometimes keys have to be discovered before you can progress, and environmental hazards such as pits and lava are not uncommon. At times, you might even have to answer a riddle in order to proceed through a dungeon unmolested, encouraging even veteran players to fall towards the habit of saving the game constantly in case a mistaken reply has dire consequences. Often, failure to answer a riddle correctly will result in a tough combat encounter from which you can continue on if you survive, but there is at least one occasion where failure to answer correctly can break the quest line. In summary, dungeon explorations ranges between the interesting and the frustrating, but rarely is it boring.

[...] Arena's main quest dungeons are surprisingly evocative. Certainly not the initial dungeon, which is a simple exercise in hacking and slashing, but the game's later dungeons are scattered with clues, which deliver deeper lore and all sorts of tales of tragedy. These tales speak of better times and ancient kingdoms felled long ago through wars and betrayals. For example, one memorable moment takes place upon entering an early dungeon, an abandoned keep where you find a sign forbidding violence and promoting peace within, followed by bloodstains and skeletal remains on the floor further down the hall. Deeper inside, you find messages suggesting that the last defenders of the keep were retreating further in hopes of finding safety. You find no further messages by them, a grim reminder that Tamriel is quite the dangerous world despite the power of the Imperial government.

The main quest dungeons are also fairly diverse in terms of aesthetic presentations. There's the initial dungeon which looks like a cross between a prison and a sewer, dungeons which take place in fallen and decrepit keeps, towers, outdoor gardens, and the game's final dungeon which starts in a palace. As the game progresses, your enemies change and become more difficult, though the last third becomes a bit repetitious through overuse of the same difficult monsters. Exploration is rewarded, with randomly generated treasure laying in hidden vaults off the direct paths. Sometimes keys have to be discovered before you can progress, and environmental hazards such as pits and lava are not uncommon. At times, you might even have to answer a riddle in order to proceed through a dungeon unmolested, encouraging even veteran players to fall towards the habit of saving the game constantly in case a mistaken reply has dire consequences. Often, failure to answer a riddle correctly will result in a tough combat encounter from which you can continue on if you survive, but there is at least one occasion where failure to answer correctly can break the quest line. In summary, dungeon explorations ranges between the interesting and the frustrating, but rarely is it boring.

Read the full article (with pictures!): RPG Codex Retrospective Review: The Elder Scrolls: Arena (1994)

[Review by Deuce Traveler]

This cover is all lies.

I had originally never intended to play The Elder Scrolls: Arena, as I'd heard enough about this imperfect creation from other RPG fans to keep me away from it. It was said that the game is unbalanced. That it feels incomplete. That its main quest and characters are shallow when compared with that of contemporary RPGs such as the Ultima games or Betrayal at Krondor. But in the end, I decided to give the game a go as part of a larger project I am working on, in order to ascertain these facts for myself. What I found was a game that is indeed quite unbalanced, with many gameplay elements that feel rushed and incomplete, and a main story arc filled with cliche fantasy tropes. And yet, the game was a total joy to play, like a B-movie that manages to be greater than the sum of its faults.

Arena was the first attempt at creating an RPG by Bethesda Softworks, a company better known at the time for its sports and action titles. The game's cover art and title do not match at all with the game that was actually released, and that's because Bethesda had initially planned to create an action game where a team of gladiators would fight their way up through a circuit of competitions with the goal of eventually becoming the Grand Champions. The code to make this game never really came together, and instead the game was redesigned, with stronger RPG elements shoe-horned in. The team-based action game was repackaged and shipped as a buggy, single character action roleplaying game, which would later be partially fixed by official patches. And so The Elder Scrolls series was born, with an origin story which would forever feed the critics of both its style and the habits of its developer.

As I mentioned before, Arena's background story is pure vanilla fantasy. There's a king that needs rescuing from an evil wizard, and you are the only one who can collect the magical artifacts needed to save said king and defeat said wizard. The game's unique spin on this fantasy trope is that your quest giver is dead, and she gives you guidance throughout your quest as a disembodied spirit. It's worth mentioning that is the first occurrence of the now familiar Elder Scrolls opening, where your character starts off as a prisoner. You begin in a rather simple dungeon which you have to escape. In this tutorial-like introduction, the game holds your hand by providing several safe areas where you can sleep to restore your hit points, and there's no time limit for you to escape your confines either. Because of this, you can easily explore the entire dungeon, discovering randomly generated equipment which can be quite powerful for your low level character.

Of course, you'll need the right kind of character to survive. Arena allows players to create a character from one of eight different races, the same races which would become integral to the established Elder Scroll lore. The player can also select one of 18 different character classes, which encompass all manner of melee, ranged and spellcasting specialists. Although attributes play an important role in character building, there's no sign of the skill system that we would come to know in later Elder Scroll games. You cannot create your own custom character class, so character creation essentially revolves around choosing a race that maximizes the benefits of the class you want to play. For instance, a 10th level Assassin gets a 30% chance of making a melee strike that does triple damage. Pick the Redguard race, which gets significant damage bonuses for melee attacks, and your high level assassin Redguard will be slaughtering his or her way through the game's later dungeons. If you just want to get into the game and play though, you can opt to answer a series of ethical questions and have it choose your character class for you. In my opinion, although you can have a lot of fun with melee and ranged characters in Arena, its most enjoyable element is breaking the game as a spellcaster. More on that later!

After you escape the introductory dungeon, you find yourself in Arena's first city. The cities, as well as the game world of Tamriel itself, are quite large, housing the numerous abodes of the general population (which can be plundered by thief players), several inns, blacksmiths, temples for healing, mage guilds, and so forth. The game tries to give a distinct feel for each of the major regions of Tamriel, with the Khajiit residing in the desert climes of Elsweyr while the Nords live in snow-filled Skyrim. The architecture is also a bit different from place to place, with details such as stained glass windows and different varieties of statues spicing up the view. Townspeople you converse with can offer you surprisingly accurate directions for reaching shops and whatnot, which is especially impressive when one considers the time period this game was made in. They also tell you rumors which add further to the game's lore.

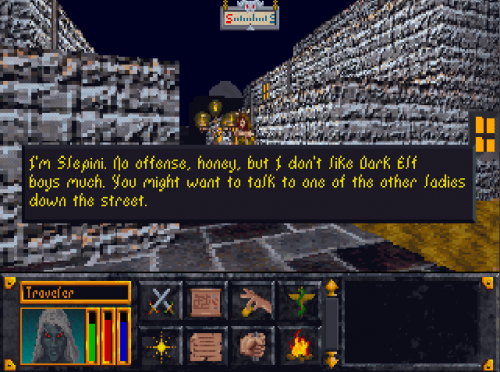

How exactly the people of Tamriel react to you depends on the region you are in and your character's race. When I played a dark elf, I was treated well in my home region of Morrowind, while the people of Hammerfell treated me with snide disdain. It's a nice touch which suggests greater problems in the Empire that the Imperial government cannot easily resolve, due to a deep history of animosity between the regional factions. As a side note, the rulers of the various cities of Arena are all lily white no matter what region they reside in, though it seems to me that this might be due to development limitations rather than because the Imperial government has installed Imperials from Cyrodiil on every single throne. Similarly, it's worth mentioning that Arena's Khajiit look quite human, while in later games they become furry cat people.

Arena has a day-night cycle, which is of importance to the player as shops will close at night, the streets will clear of everyone except thieves and ladies of ill repute, and various humanoids will invade the towns, doing no damage but mingling with their less than savory citizens. In fact, your character is the only one they will attack on sight, leading me to suspect that they have some sort of commercial relationship with the good townsfolk. Maybe the people lock up for the night and leave the city to the orcs and goblins in order to allow these crude visitors to shop on the black market and proposition the local prostitutes. And then your puritan character, who can't do any of those things no matter what dialogue options you choose, shows up in town and interrupts these profitably nocturnal libertarian transactions, resulting in angered humanoids and non-interference from the townsfolk towards whom you have just caused a financial loss. If anybody has another theory on why the citizenry and monsters seem to get along while you are always jumped upon approach, I would love to hear it!

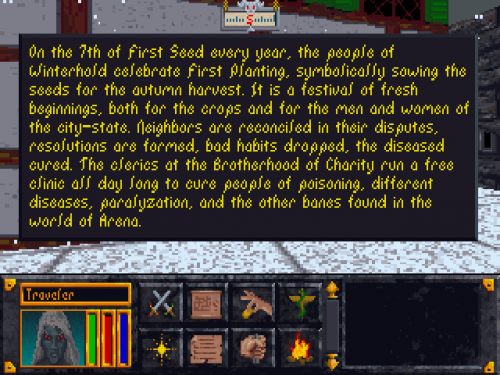

On occasion, you might enter a town or city right when they are in the midst of a local holiday, and while that may mean celebrations with alcohol and debauchery for most people, for your character it basically means discounts at shops. Inns are probably the most important establishment for any player, open at night and serving as a place to rest and restore hit points without interruption. You'll often use them simply to wait out the night so you can shop during the day. Temples are for healing characters who aren't equipped with potions or talented in magic, and the mage guilds are vitally important for those who wish to identify items, learn new spells, purchase magical equipment or design their own magic. Finally, blacksmiths can sell you armor and weapons, and also repair them as they become worn from use. Of course, all of these wonderful services cost money, and so off you will go in pursuit of lucrative side quests and dungeons.

It's like getting a quest to go get a quest. Luckily, he can also tell me where to find the palace.

Arena's towns have plenty of side quests available, most of which consist of escort and FedEx-type missions, made slightly more interesting through the imposition of time limits. Unfortunately, they normally don't pay as well as a quick jaunt into the nearest dungeon, and so I found these mundane quests not worth the hassle. Sometimes, though, you'll be sold some information that reveals the location of a valuable magical artifact. These treasure hunting side quests are worth completing, as they can result in an important boost to your equipment loadout. However, even they feel quite dull in comparison to the more unique main quest dungeons. As big as Arena may seem, it has a lot of filler locations that exist only to give the illusion of size rather than delivering any actual substance or unique lore. This, of course, remains a problem in every Elder Scrolls game that came after it.

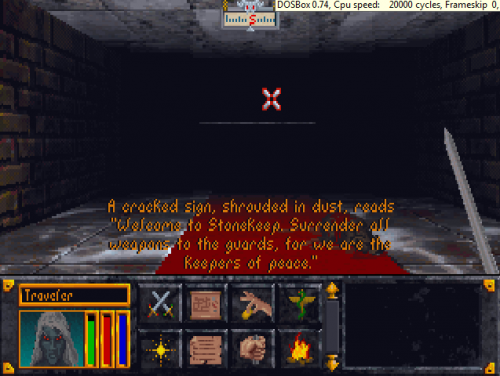

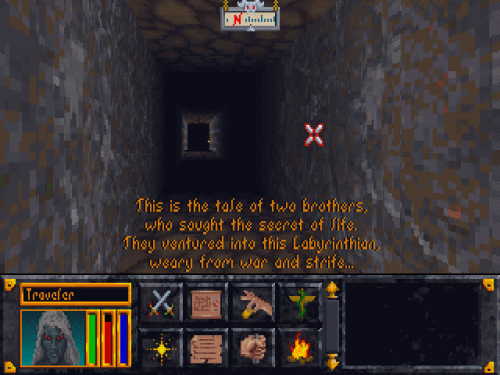

Arena's main quest dungeons are surprisingly evocative. Certainly not the initial dungeon, which is a simple exercise in hacking and slashing, but the game's later dungeons are scattered with clues, which deliver deeper lore and all sorts of tales of tragedy. These tales speak of better times and ancient kingdoms felled long ago through wars and betrayals. For example, one memorable moment takes place upon entering an early dungeon, an abandoned keep where you find a sign forbidding violence and promoting peace within, followed by bloodstains and skeletal remains on the floor further down the hall. Deeper inside, you find messages suggesting that the last defenders of the keep were retreating further in hopes of finding safety. You find no further messages by them, a grim reminder that Tamriel is quite the dangerous world despite the power of the Imperial government.

The main quest dungeons are also fairly diverse in terms of aesthetic presentations. There's the initial dungeon which looks like a cross between a prison and a sewer, dungeons which take place in fallen and decrepit keeps, towers, outdoor gardens, and the game's final dungeon which starts in a palace. As the game progresses, your enemies change and become more difficult, though the last third becomes a bit repetitious through overuse of the same difficult monsters. Exploration is rewarded, with randomly generated treasure laying in hidden vaults off the direct paths. Sometimes keys have to be discovered before you can progress, and environmental hazards such as pits and lava are not uncommon. At times, you might even have to answer a riddle in order to proceed through a dungeon unmolested, encouraging even veteran players to fall towards the habit of saving the game constantly in case a mistaken reply has dire consequences. Often, failure to answer a riddle correctly will result in a tough combat encounter from which you can continue on if you survive, but there is at least one occasion where failure to answer correctly can break the quest line. In summary, dungeon explorations ranges between the interesting and the frustrating, but rarely is it boring.

Arena's monsters can be quite dangerous when you first encounter them, especially when you are still learning their capabilities. Get too close to a monster who is tough in melee and it might quickly wipe the floor with you. Try to attack another from a distance with ranged attacks and you might find that it has deadly ranged attacks of its own. Many monsters in the late game are immune to weapons made from low quality materials, and are therefore impossible to defeat until you find something better in a dungeon or at a blacksmith's shop. Luckily, the monster AI is utterly stupid, and combat is buggy in a helpful sort of way. Enemies will often become stuck when trying to walk through partly open doorways, leaving them vulnerable to a number of tactics. They will also happily fire into their own ranks when trying to attack you from a distance, which is both incredibly helpful and incredibly funny. When it comes to efficiency, nothing quite beats casting a spell of Protection From Magic and then stepping into a crowd of fireball-slinging monsters.

In fact, there are many other glorious ways in which you can use spellcasting to completely break this game. Sure, you can cast Levitate to float over pits, and learn Cure Poison and Cure Disease spells in order to rid yourself of disastrous maladies. But you can also cast spells that allow you to destroy dungeon walls and take shortcuts through mazes, absorb the mana of incoming enemy wizard spells, or turn yourself invisible so you can gradually wear down your enemies while they stand and do nothing. If you play as a spellcaster, the game's final dungeon is incredibly easy - you absorb the mana of the spells flung at you and convert them into extremely deadly spells of your own that the enemy seems to have no immunity against. It's as if you are the only person in Tamriel that knows such spells despite the fact that they're available for purchase in every shop, gloriously carving a bloody path through your pitiful foes. But you can go even further than that if you drop the poorly designed official spells and spend some time creating your own. The trick is to lower the spells' base effects and jack up the per-level effects, which creates spells which have a similar casting cost to the official ones, but with a much greater effect in the late game. Here are some examples:

Fire Dart (Official Spell)

Targets: 1 target at range

Save vs Fire

Casting Cost: 5

Effect: 1-2 + 3-4/level damage

10th Level Caster Result: 31-42 damage, 36 on average

Wizard's Fire (Official Spell)

Targets: 1 target at range

Save vs Fire

Casting Cost: 13

Effect: 1-15 + 1-6/level damage

10th Level Caster Result: 11-75 damage, 43 on average

Vaarsuvius (My Custom Spell)

Targets: Touch

Save vs Fire

Casting Cost: 5

Effect: 1 + 1-20/level damage

10th Level Caster Result: 11-201 damage, 106 on average

My custom fire-based spell does require a touch attack, but since I found that I was usually better off closing in on the enemy anyway, it's obviously superior. I was having a hell of a time with ice golems before I made it. Look at the casting costs. My spell does more than twice the damage as Wizard's Fire for 38% of the cost.

Here is the game's official protection spell, and mine:

Shield (Official Spell)

Casting Cost: 17

Effect: 15 + 5/level hit point shield

10th Level Caster Result: 70 hit point shield

ShieldsUp! (My Custom Spell)

Casting Cost: 15

Effect: 1 + 10/level hit point shield

10th Level Caster Result: 111 hit point shield

So for 2 mana points less, I get a shield spell that's more than 50% stronger than the game's version. The Codex could probably have loads of fun with a thread dedicated to creating wacky custom spells in Arena. Perhaps with more development time, the game would have had a better selection of purchasable spells available.

Because Arena's monsters are not all that varied in terms of behavior and tactics, killing them en masse is a breeze for a late game spellcaster with custom spells, but agonizingly repetitious for a non-spellcaster who can't do massive damage with single attacks. I can't imagine playing a thief or a fighter all the way to the end of this game, because the lack of spell power makes these characters very vulnerable to the hordes of enemy spellcasters found in its final dungeon. In contrast, as a spellcaster, the first time I saw a lich, I was a bit worried...until I killed it with three casts of a low cost attack spell that I had made. Liches are supposed to be the toughest monster in the game, but I was never once hurt by one. All they managed to do was charge up my mana, thanks to my spell absorption shell.

The game's main villain isn't very intimidating. I actually felt kind of sorry for him. He was throwing orcs at me when I had just completed a dungeon full of medusas and wraiths. He kept taunting me, telling me I couldn't stop him while I was busy killing off his minions, putting together the artifact pieces he had spent so much time on hiding, slaughtering all of personal guards in the final dungeon, and finally using the artifact he had mocked for being useless to end him. I found that my spellcaster was a much scarier threat than the end boss. His bug-ridden minions should have been working for me.

The corpses of dead animals in Arena, such as wolves and spiders, contain dozens of gold coins. I like to imagine they're from all the previous adventurers they've devoured. Unfortunately, not all of the game's oddities and bugs work in the player's favor. Sure, it was funny the first time I saw rats open a door so they could attack me. It wasn't as funny when a pack of wolves did the same thing and nearly killed my unprepared battlemage. Another time, I couldn't leave a room in the inn I was staying in because the innkeeper and another guest, who were nowhere nearby, had somehow become associated with its door. I had to click on different parts of the door until I found a spot that actually opened the darn thing so I could get out. And then there was the time I couldn't deactivate the steal functionality and kept getting into random fights with omniscient guards (another Elder Scrolls trope) because of it.

There's another glitch in Arena that causes enemies to sometimes become invisible, only appearing when they attack you. You might unknowingly walk by an enemy without seeing them until they are attacking you from behind, so you'll want to have the sound on so you can at least hear them. The game also has a lag problem, especially in its latter portions, which I attribute to the fact that there are more monsters in the late game dungeons, since it seemed to be reduced as I progressively killed them off. Finally, the game crashed during the ending cinematic, so I had to watch it on somebody's YouTube Let's Play.

All in all, I had a blast with Arena despite the negatives. That might be mostly because I had my custom-made god mode on (custom-made shield spell, custom-made fire resistance spell, custom-made spell absorption spell, and custom-made invisibility spell) and towards the end of the game was breaking pretty much everything. It was exactly the kind of bug-ridden incomplete game I had expected it would be. What was unexpected was the amount of fun I had playing it.

So now I have completed three Elder Scrolls games - Arena, Morrowind and Oblivion. Out of the three, Morrowind is the one that I enjoyed the most, and the one I would choose to come back to if given the choice. But gauging whether I'd rather play Arena or Oblivion is a tough choice. Oblivion has more responsive controls and is less prone to crashing. It also has more to do in it, mostly due to mods but also due to a rare few quality side quests like the Whodunit quest. If I had to choose one of them, it would be Oblivion with mods. But if we're talking unmodded and only playing through the main quest, I definitely choose Arena. The main quest of Oblivion is quite boring. The first Oblivion gate is interesting because of how alien the terrain looks, but then every single one of them after that looks and feels the same. Compare that to Arena, where it's obvious that much effort went into changing up the main quest dungeons. Both games suffer from limited bestiaries and dull non-main quest dungeons, but the main quest dungeon design is much better in Arena. Anyway, thanks for reading the review. I'm off to play Daggerfall.

This cover is all lies.

Arena was the first attempt at creating an RPG by Bethesda Softworks, a company better known at the time for its sports and action titles. The game's cover art and title do not match at all with the game that was actually released, and that's because Bethesda had initially planned to create an action game where a team of gladiators would fight their way up through a circuit of competitions with the goal of eventually becoming the Grand Champions. The code to make this game never really came together, and instead the game was redesigned, with stronger RPG elements shoe-horned in. The team-based action game was repackaged and shipped as a buggy, single character action roleplaying game, which would later be partially fixed by official patches. And so The Elder Scrolls series was born, with an origin story which would forever feed the critics of both its style and the habits of its developer.

As I mentioned before, Arena's background story is pure vanilla fantasy. There's a king that needs rescuing from an evil wizard, and you are the only one who can collect the magical artifacts needed to save said king and defeat said wizard. The game's unique spin on this fantasy trope is that your quest giver is dead, and she gives you guidance throughout your quest as a disembodied spirit. It's worth mentioning that is the first occurrence of the now familiar Elder Scrolls opening, where your character starts off as a prisoner. You begin in a rather simple dungeon which you have to escape. In this tutorial-like introduction, the game holds your hand by providing several safe areas where you can sleep to restore your hit points, and there's no time limit for you to escape your confines either. Because of this, you can easily explore the entire dungeon, discovering randomly generated equipment which can be quite powerful for your low level character.

Of course, you'll need the right kind of character to survive. Arena allows players to create a character from one of eight different races, the same races which would become integral to the established Elder Scroll lore. The player can also select one of 18 different character classes, which encompass all manner of melee, ranged and spellcasting specialists. Although attributes play an important role in character building, there's no sign of the skill system that we would come to know in later Elder Scroll games. You cannot create your own custom character class, so character creation essentially revolves around choosing a race that maximizes the benefits of the class you want to play. For instance, a 10th level Assassin gets a 30% chance of making a melee strike that does triple damage. Pick the Redguard race, which gets significant damage bonuses for melee attacks, and your high level assassin Redguard will be slaughtering his or her way through the game's later dungeons. If you just want to get into the game and play though, you can opt to answer a series of ethical questions and have it choose your character class for you. In my opinion, although you can have a lot of fun with melee and ranged characters in Arena, its most enjoyable element is breaking the game as a spellcaster. More on that later!

After you escape the introductory dungeon, you find yourself in Arena's first city. The cities, as well as the game world of Tamriel itself, are quite large, housing the numerous abodes of the general population (which can be plundered by thief players), several inns, blacksmiths, temples for healing, mage guilds, and so forth. The game tries to give a distinct feel for each of the major regions of Tamriel, with the Khajiit residing in the desert climes of Elsweyr while the Nords live in snow-filled Skyrim. The architecture is also a bit different from place to place, with details such as stained glass windows and different varieties of statues spicing up the view. Townspeople you converse with can offer you surprisingly accurate directions for reaching shops and whatnot, which is especially impressive when one considers the time period this game was made in. They also tell you rumors which add further to the game's lore.

How exactly the people of Tamriel react to you depends on the region you are in and your character's race. When I played a dark elf, I was treated well in my home region of Morrowind, while the people of Hammerfell treated me with snide disdain. It's a nice touch which suggests greater problems in the Empire that the Imperial government cannot easily resolve, due to a deep history of animosity between the regional factions. As a side note, the rulers of the various cities of Arena are all lily white no matter what region they reside in, though it seems to me that this might be due to development limitations rather than because the Imperial government has installed Imperials from Cyrodiil on every single throne. Similarly, it's worth mentioning that Arena's Khajiit look quite human, while in later games they become furry cat people.

Arena has a day-night cycle, which is of importance to the player as shops will close at night, the streets will clear of everyone except thieves and ladies of ill repute, and various humanoids will invade the towns, doing no damage but mingling with their less than savory citizens. In fact, your character is the only one they will attack on sight, leading me to suspect that they have some sort of commercial relationship with the good townsfolk. Maybe the people lock up for the night and leave the city to the orcs and goblins in order to allow these crude visitors to shop on the black market and proposition the local prostitutes. And then your puritan character, who can't do any of those things no matter what dialogue options you choose, shows up in town and interrupts these profitably nocturnal libertarian transactions, resulting in angered humanoids and non-interference from the townsfolk towards whom you have just caused a financial loss. If anybody has another theory on why the citizenry and monsters seem to get along while you are always jumped upon approach, I would love to hear it!

On occasion, you might enter a town or city right when they are in the midst of a local holiday, and while that may mean celebrations with alcohol and debauchery for most people, for your character it basically means discounts at shops. Inns are probably the most important establishment for any player, open at night and serving as a place to rest and restore hit points without interruption. You'll often use them simply to wait out the night so you can shop during the day. Temples are for healing characters who aren't equipped with potions or talented in magic, and the mage guilds are vitally important for those who wish to identify items, learn new spells, purchase magical equipment or design their own magic. Finally, blacksmiths can sell you armor and weapons, and also repair them as they become worn from use. Of course, all of these wonderful services cost money, and so off you will go in pursuit of lucrative side quests and dungeons.

It's like getting a quest to go get a quest. Luckily, he can also tell me where to find the palace.

Arena's towns have plenty of side quests available, most of which consist of escort and FedEx-type missions, made slightly more interesting through the imposition of time limits. Unfortunately, they normally don't pay as well as a quick jaunt into the nearest dungeon, and so I found these mundane quests not worth the hassle. Sometimes, though, you'll be sold some information that reveals the location of a valuable magical artifact. These treasure hunting side quests are worth completing, as they can result in an important boost to your equipment loadout. However, even they feel quite dull in comparison to the more unique main quest dungeons. As big as Arena may seem, it has a lot of filler locations that exist only to give the illusion of size rather than delivering any actual substance or unique lore. This, of course, remains a problem in every Elder Scrolls game that came after it.

Arena's main quest dungeons are surprisingly evocative. Certainly not the initial dungeon, which is a simple exercise in hacking and slashing, but the game's later dungeons are scattered with clues, which deliver deeper lore and all sorts of tales of tragedy. These tales speak of better times and ancient kingdoms felled long ago through wars and betrayals. For example, one memorable moment takes place upon entering an early dungeon, an abandoned keep where you find a sign forbidding violence and promoting peace within, followed by bloodstains and skeletal remains on the floor further down the hall. Deeper inside, you find messages suggesting that the last defenders of the keep were retreating further in hopes of finding safety. You find no further messages by them, a grim reminder that Tamriel is quite the dangerous world despite the power of the Imperial government.

The main quest dungeons are also fairly diverse in terms of aesthetic presentations. There's the initial dungeon which looks like a cross between a prison and a sewer, dungeons which take place in fallen and decrepit keeps, towers, outdoor gardens, and the game's final dungeon which starts in a palace. As the game progresses, your enemies change and become more difficult, though the last third becomes a bit repetitious through overuse of the same difficult monsters. Exploration is rewarded, with randomly generated treasure laying in hidden vaults off the direct paths. Sometimes keys have to be discovered before you can progress, and environmental hazards such as pits and lava are not uncommon. At times, you might even have to answer a riddle in order to proceed through a dungeon unmolested, encouraging even veteran players to fall towards the habit of saving the game constantly in case a mistaken reply has dire consequences. Often, failure to answer a riddle correctly will result in a tough combat encounter from which you can continue on if you survive, but there is at least one occasion where failure to answer correctly can break the quest line. In summary, dungeon explorations ranges between the interesting and the frustrating, but rarely is it boring.

Arena's monsters can be quite dangerous when you first encounter them, especially when you are still learning their capabilities. Get too close to a monster who is tough in melee and it might quickly wipe the floor with you. Try to attack another from a distance with ranged attacks and you might find that it has deadly ranged attacks of its own. Many monsters in the late game are immune to weapons made from low quality materials, and are therefore impossible to defeat until you find something better in a dungeon or at a blacksmith's shop. Luckily, the monster AI is utterly stupid, and combat is buggy in a helpful sort of way. Enemies will often become stuck when trying to walk through partly open doorways, leaving them vulnerable to a number of tactics. They will also happily fire into their own ranks when trying to attack you from a distance, which is both incredibly helpful and incredibly funny. When it comes to efficiency, nothing quite beats casting a spell of Protection From Magic and then stepping into a crowd of fireball-slinging monsters.

In fact, there are many other glorious ways in which you can use spellcasting to completely break this game. Sure, you can cast Levitate to float over pits, and learn Cure Poison and Cure Disease spells in order to rid yourself of disastrous maladies. But you can also cast spells that allow you to destroy dungeon walls and take shortcuts through mazes, absorb the mana of incoming enemy wizard spells, or turn yourself invisible so you can gradually wear down your enemies while they stand and do nothing. If you play as a spellcaster, the game's final dungeon is incredibly easy - you absorb the mana of the spells flung at you and convert them into extremely deadly spells of your own that the enemy seems to have no immunity against. It's as if you are the only person in Tamriel that knows such spells despite the fact that they're available for purchase in every shop, gloriously carving a bloody path through your pitiful foes. But you can go even further than that if you drop the poorly designed official spells and spend some time creating your own. The trick is to lower the spells' base effects and jack up the per-level effects, which creates spells which have a similar casting cost to the official ones, but with a much greater effect in the late game. Here are some examples:

Fire Dart (Official Spell)

Targets: 1 target at range

Save vs Fire

Casting Cost: 5

Effect: 1-2 + 3-4/level damage

10th Level Caster Result: 31-42 damage, 36 on average

Wizard's Fire (Official Spell)

Targets: 1 target at range

Save vs Fire

Casting Cost: 13

Effect: 1-15 + 1-6/level damage

10th Level Caster Result: 11-75 damage, 43 on average

Vaarsuvius (My Custom Spell)

Targets: Touch

Save vs Fire

Casting Cost: 5

Effect: 1 + 1-20/level damage

10th Level Caster Result: 11-201 damage, 106 on average

My custom fire-based spell does require a touch attack, but since I found that I was usually better off closing in on the enemy anyway, it's obviously superior. I was having a hell of a time with ice golems before I made it. Look at the casting costs. My spell does more than twice the damage as Wizard's Fire for 38% of the cost.

Here is the game's official protection spell, and mine:

Shield (Official Spell)

Casting Cost: 17

Effect: 15 + 5/level hit point shield

10th Level Caster Result: 70 hit point shield

ShieldsUp! (My Custom Spell)

Casting Cost: 15

Effect: 1 + 10/level hit point shield

10th Level Caster Result: 111 hit point shield

So for 2 mana points less, I get a shield spell that's more than 50% stronger than the game's version. The Codex could probably have loads of fun with a thread dedicated to creating wacky custom spells in Arena. Perhaps with more development time, the game would have had a better selection of purchasable spells available.

Because Arena's monsters are not all that varied in terms of behavior and tactics, killing them en masse is a breeze for a late game spellcaster with custom spells, but agonizingly repetitious for a non-spellcaster who can't do massive damage with single attacks. I can't imagine playing a thief or a fighter all the way to the end of this game, because the lack of spell power makes these characters very vulnerable to the hordes of enemy spellcasters found in its final dungeon. In contrast, as a spellcaster, the first time I saw a lich, I was a bit worried...until I killed it with three casts of a low cost attack spell that I had made. Liches are supposed to be the toughest monster in the game, but I was never once hurt by one. All they managed to do was charge up my mana, thanks to my spell absorption shell.

The game's main villain isn't very intimidating. I actually felt kind of sorry for him. He was throwing orcs at me when I had just completed a dungeon full of medusas and wraiths. He kept taunting me, telling me I couldn't stop him while I was busy killing off his minions, putting together the artifact pieces he had spent so much time on hiding, slaughtering all of personal guards in the final dungeon, and finally using the artifact he had mocked for being useless to end him. I found that my spellcaster was a much scarier threat than the end boss. His bug-ridden minions should have been working for me.

The corpses of dead animals in Arena, such as wolves and spiders, contain dozens of gold coins. I like to imagine they're from all the previous adventurers they've devoured. Unfortunately, not all of the game's oddities and bugs work in the player's favor. Sure, it was funny the first time I saw rats open a door so they could attack me. It wasn't as funny when a pack of wolves did the same thing and nearly killed my unprepared battlemage. Another time, I couldn't leave a room in the inn I was staying in because the innkeeper and another guest, who were nowhere nearby, had somehow become associated with its door. I had to click on different parts of the door until I found a spot that actually opened the darn thing so I could get out. And then there was the time I couldn't deactivate the steal functionality and kept getting into random fights with omniscient guards (another Elder Scrolls trope) because of it.

There's another glitch in Arena that causes enemies to sometimes become invisible, only appearing when they attack you. You might unknowingly walk by an enemy without seeing them until they are attacking you from behind, so you'll want to have the sound on so you can at least hear them. The game also has a lag problem, especially in its latter portions, which I attribute to the fact that there are more monsters in the late game dungeons, since it seemed to be reduced as I progressively killed them off. Finally, the game crashed during the ending cinematic, so I had to watch it on somebody's YouTube Let's Play.

All in all, I had a blast with Arena despite the negatives. That might be mostly because I had my custom-made god mode on (custom-made shield spell, custom-made fire resistance spell, custom-made spell absorption spell, and custom-made invisibility spell) and towards the end of the game was breaking pretty much everything. It was exactly the kind of bug-ridden incomplete game I had expected it would be. What was unexpected was the amount of fun I had playing it.

So now I have completed three Elder Scrolls games - Arena, Morrowind and Oblivion. Out of the three, Morrowind is the one that I enjoyed the most, and the one I would choose to come back to if given the choice. But gauging whether I'd rather play Arena or Oblivion is a tough choice. Oblivion has more responsive controls and is less prone to crashing. It also has more to do in it, mostly due to mods but also due to a rare few quality side quests like the Whodunit quest. If I had to choose one of them, it would be Oblivion with mods. But if we're talking unmodded and only playing through the main quest, I definitely choose Arena. The main quest of Oblivion is quite boring. The first Oblivion gate is interesting because of how alien the terrain looks, but then every single one of them after that looks and feels the same. Compare that to Arena, where it's obvious that much effort went into changing up the main quest dungeons. Both games suffer from limited bestiaries and dull non-main quest dungeons, but the main quest dungeon design is much better in Arena. Anyway, thanks for reading the review. I'm off to play Daggerfall.

There are 44 comments on RPG Codex Retrospective Review: The Elder Scrolls: Arena (1994)