RPG Codex Review: The Banner Saga

RPG Codex Review: The Banner Saga

Review - posted by Crooked Bee on Mon 15 June 2015, 16:52:26

Tags: Stoic Studio; The Banner SagaThe northern wind is stiff, but I could never tell with this featureless terrain if not for the red banner flapping. The combat variety may not be great, but I press on. I feel the game's heart and hear it sing its Nordic blues. Most of my characters are dead, and I blame the fake C&C for lulling me into a false sense of security. I am playing Stoic Studio's 2014 tactical RPG The Banner Saga.

So would my review go. But thankfully I am not the reviewer. It is rather the esteemed community member Bubbles. So have a few snippets from his take on the game:

Read the full article: RPG Codex Review: The Banner Saga

So would my review go. But thankfully I am not the reviewer. It is rather the esteemed community member Bubbles. So have a few snippets from his take on the game:

The past year has given us strong evidence to suggest that the RPG industry would be tremendously helped if our Canadian friends were to cease operations immediately and released all their herded up talent into the indie wilderness. Stoic, the studio behind The Banner Saga, follows in the tradition of other ex-BioWare developers who, upon leaving the company, suddenly began to exhibit a talent for making good role playing games (Daniel Fedor's NEO Scavenger being the most prominent other example). In fact, the crowdfunded Banner Saga is more successful at offering a “BioWare experience” than anything that company has put out since Dragon Age: Origins. This game features a compelling story, well-drawn characters operating under a constant threat of perma-death, choices with a wide variety of consequences, and a surprisingly complex and novel combat system that prevents the battles from feeling like repetitive trash combat. It is also very pretty.

[...] After close inspection, I can attest that Stoic's C&C system is quite cunningly implemented. Let us start with what would normally be the worst consequence of them all: you lose a battle against a horde of merciless enemies. Your heroes all fall unconscious on the battle field, and all hope is lost. What happens now? Reload to last save? That would be the bland, safe choice, allowing you to simply redo the battle until you get it right and can reap the rewards of victory. So, no, that is not what happens. Instead, a text window pops up and tells you how you got saved. Usually, some of your nameless supporting troops rushed to your aid and hurtled themselves onto the spears of your enemies, thus paying the ultimate price in the service of a smooth gameplay experience. Rarely, one of your less important companions made a heroic sacrifice, forever removing himself from your party roster in the process. Sometimes you wake up, battered and defeated, without really knowing what happened. Much e-blood has already been spilled over this mechanic; many of the game's harshest critics absolutely abhor the fact that it is (almost) impossible to get a game over screen from a party wipe. Other, more tolerant and progressive minds have come to appreciate the advantages of this implementation.

[...] The Banner Saga has a good battle system. Before the game's release, the system was tested in a multiplayer Free-to-Play game – The Banner Saga: Factions – which was released a full year before the single player game. Being able to study their players in a competitive environment provided Stoic with ample opportunities to discover the weaknesses of their systems design; the result has been a highly polished battle system that feels well thought out and fully coherent. That is not to say that this system is uncontroversial; in fact, it is probably the most hotly debated aspect of the game.

[...] The Banner Saga is an immensely unique, and, by no coincidence, immensely good game that combines great artistic design and robust C&C mechanics with a highly entertaining and deceptively complex battle system. The Banner Saga has only a few outright flaws; the shoddy dialogues and the constant need to click-click-click through them line by line are a blemish on an otherwise engaging narrative. Moreover, the startling lack of enemy variety and the relatively dumb AI keep the battle system from realizing its potential for true tactical greatness. The game's system of choices and consequences also has far less of an impact on the story than Stoic's PR department has been trying to claim; nonetheless, it still offers an engaging and immersive range of decisions that will directly influence your battle performance and can occasionally result in major character deaths.

I suspect that The Banner Saga will always be the subject of great controversy; it has a kind of self-assured swagger, flaunting all of its little weirdnesses and weaknesses without making much of an effort to look like a typical tactical cRPG or a typical casual story game. The game features heaps upon heaps of idiosyncratic gameplay systems, like the strange combination of a broad C&C system with a fully pre-determined linear story, the fact that you will rarely if ever be able to see a "game over" screen, the "sit back and immerse yourself" approach to map travel, and a whole slew of novel and deeply unrealistic combat mechanics. You may choose to accept or reject these mechanics according to your personal preferences; all I can tell you is that all of these elements stand in the service of a fully coherent and extremely tightly designed gameplay experience that I deeply enjoyed playing through.

[...] After close inspection, I can attest that Stoic's C&C system is quite cunningly implemented. Let us start with what would normally be the worst consequence of them all: you lose a battle against a horde of merciless enemies. Your heroes all fall unconscious on the battle field, and all hope is lost. What happens now? Reload to last save? That would be the bland, safe choice, allowing you to simply redo the battle until you get it right and can reap the rewards of victory. So, no, that is not what happens. Instead, a text window pops up and tells you how you got saved. Usually, some of your nameless supporting troops rushed to your aid and hurtled themselves onto the spears of your enemies, thus paying the ultimate price in the service of a smooth gameplay experience. Rarely, one of your less important companions made a heroic sacrifice, forever removing himself from your party roster in the process. Sometimes you wake up, battered and defeated, without really knowing what happened. Much e-blood has already been spilled over this mechanic; many of the game's harshest critics absolutely abhor the fact that it is (almost) impossible to get a game over screen from a party wipe. Other, more tolerant and progressive minds have come to appreciate the advantages of this implementation.

[...] The Banner Saga has a good battle system. Before the game's release, the system was tested in a multiplayer Free-to-Play game – The Banner Saga: Factions – which was released a full year before the single player game. Being able to study their players in a competitive environment provided Stoic with ample opportunities to discover the weaknesses of their systems design; the result has been a highly polished battle system that feels well thought out and fully coherent. That is not to say that this system is uncontroversial; in fact, it is probably the most hotly debated aspect of the game.

[...] The Banner Saga is an immensely unique, and, by no coincidence, immensely good game that combines great artistic design and robust C&C mechanics with a highly entertaining and deceptively complex battle system. The Banner Saga has only a few outright flaws; the shoddy dialogues and the constant need to click-click-click through them line by line are a blemish on an otherwise engaging narrative. Moreover, the startling lack of enemy variety and the relatively dumb AI keep the battle system from realizing its potential for true tactical greatness. The game's system of choices and consequences also has far less of an impact on the story than Stoic's PR department has been trying to claim; nonetheless, it still offers an engaging and immersive range of decisions that will directly influence your battle performance and can occasionally result in major character deaths.

I suspect that The Banner Saga will always be the subject of great controversy; it has a kind of self-assured swagger, flaunting all of its little weirdnesses and weaknesses without making much of an effort to look like a typical tactical cRPG or a typical casual story game. The game features heaps upon heaps of idiosyncratic gameplay systems, like the strange combination of a broad C&C system with a fully pre-determined linear story, the fact that you will rarely if ever be able to see a "game over" screen, the "sit back and immerse yourself" approach to map travel, and a whole slew of novel and deeply unrealistic combat mechanics. You may choose to accept or reject these mechanics according to your personal preferences; all I can tell you is that all of these elements stand in the service of a fully coherent and extremely tightly designed gameplay experience that I deeply enjoyed playing through.

Read the full article: RPG Codex Review: The Banner Saga

[Review by Bubbles]

The Banner Saga: Chapter One

Kickstarter, the great disappointer, makes fools of us all. Ambitious mammoth projects have gobbled up millions of gamer dollars and launched to great fanfare, only to dash upon the jagged rocks of developer incompetence. Thus with Pillars of Eternity, thus with Wasteland 2, and thus, no doubt, with countless other miserable failures to come. Where are the great games of our modern era? Whither the creative force, the clarity of vision that drove the RPG genre to greatness in the past? Whither the industry veterans, the self-assured maniacs who could produce industry-changing ideas on command? Whither the stern, yet noble managers of yesteryear, the wizened masterminds capable of turning out sleek, polished, and eminently enjoyable gaming experiences? It turns out they were working at BioWare all along.

In fact, the past year has given us strong evidence to suggest that the RPG industry would be tremendously helped if our Canadian friends were to cease operations immediately and released all their herded up talent into the indie wilderness. Stoic, the studio behind The Banner Saga, follows in the tradition of other ex-BioWare developers who, upon leaving the company, suddenly began to exhibit a talent for making good role playing games (Daniel Fedor's NEO Scavenger being the most prominent other example). In fact, the crowdfunded Banner Saga is more successful at offering a “BioWare experience” than anything that company has put out since Dragon Age: Origins. This game features a compelling story, well-drawn characters operating under a constant threat of perma-death, choices with a wide variety of consequences, and a surprisingly complex and novel combat system that prevents the battles from feeling like repetitive trash combat. It is also very pretty.

Saga of Banners

If I had to guess how Stoic used their Kickstarter budget for this game, I would wager that they spent most of their money on visual and sound design. The Banner Saga's score presents a surprisingly effective combination of moody chants and rousing battle marches, featuring plenty of drums, string instruments, and grizzled Icelandic singers. It complements the gameplay nicely, providing the proper backdrop for a lonely journey through a harsh northern landscape. The game's locations also offer unique sound work; when woodcutters are around, you will hear axes and labourer's chatter, while a settlement of cattle herders presents you with a symphony of gentle mooing sounds. Visually, the game shows off a distinct 2D art style with a rich colour palette, suffused with intricate details. Particularly noteworthy are the rotoscoped combat animations, which manage to express a tremendous amount of kinetic energy. With so many modern RPGs featuring limp melee animations, it is very nice to a see a game where the combatants actually contort their bodies and visibly take time to recover while swinging their heavy weapons around. The fact that the game's visual design is also fully coherent and without any obvious flaws should generally not be worthy of note, much less of praise; however, after seeing so many strange problems with recent games – I recall the mismatched NPC models in Wasteland 2 and the sloppy area lighting and perspective issues in the Shadowrun games – it is nice to see an indie RPG that simply looks consistently good. But is there any depth to the design? Is “great style” just shorthand for shallow narrative design and simple gameplay? Let us investigate.

The dominant visual motif of The Banner Saga – in fact, it is part of the title, shown behind the title and sprawled over the title screen, – is the great red banner of the group of travellers whose story is told in the course of the game. As the group embarks on its journey through a war-torn Nordic fantasy realm, that banner unfurls to an implausible length, stretching itself like a shelter over a troop of dozens of peasants and soldiers. About an hour into the game, the banner's meaning is explained by the young girl who mends and maintains it; its fabric is embroidered with the stories of the people who travel beneath it, telling their history as they live it. Thus, the Banner is not an empty symbol designed to look vaguely cool and help out the marketing department; it is a piece of narrative expression that forms the core of the game's visual design. Smaller, multi-coloured banners pervade the game's UI; from skill banners to combat reward banners to menu option banners, just about every aspect of visual design has been carefully shaped to include the game's central motif.

The advantages of such a strong focus on art design are most apparent when the group is on the road. As part of the strictly linear storyline, the characters choose their own destinations and auto-travel without any player input, traversing a 2D landscape from right to left or from left to right until they reach a settlement. Player control is confined to choosing when to set up camp and dealing with random event windows that pop up during the journey. These journeys could, potentially, be immensely boring, serving as nothing more than glorified screen savers wasting player time until the next gameplay segment arrives. However, as the rolling hills of the background landscape combined with the gently undulating movements of the banner and the moody pieces of travelling music, I found myself actually, genuinely immersed in the scenery. I got the impression that what I was seeing and what I was hearing was worth paying attention to. In fact, one of the game's greatest strengths lies in those unexpected moments when, after a long journey, the travel music transitions into a different tune, the terrain begins to change, and you witness a new uplifting or terrifying (usually terrifying) sight coming into view. This strong sense of atmosphere keeps the travelling sequences engaging throughout most of the game's 15-hour playing time. Only the final journey feels like it drags on for a few minutes longer than it should, and fells rather dull and exhaustive. There is a perfectly very good thematic reason to evoke this kind of response at this stage in the story, but intentional tedium is still tedium.

The game's setting is mostly standard fantasy stuff, but with enough mysterious details to be interesting in its own right. During the opening cutscene, you are informed that the gods have died, abandoning their followers, while the sun has stopped in the sky. Humans have made peace with another race, the Varl, horned giants (notice the similarity to Dragon Age 2's Qunari) who are perpetually in decline because they are all male and thus cannot breed. Their common enemy are the Dredge – an ancient race lurking in the frozen wastelands to the north – who have been mysteriously silent as of late. The idea of a post-Götterdämmerung world being able to move forward and sustain itself on the basis of pure mortal tenacity is a reasonably intriguing conceit for an RPG setting, and the game makes good use of that concept while launching its multiple human and Varl protagonists into an ever escalating series of catastrophes. Keep in mind, however, that this is very much a “heroes' journey” type of narrative. All of your playable characters (over 20 in total, with three POV characters who can make decisions in dialogues and event windows)are fully pre-defined in their identities, and while one or two of them will turn out to be proper scum, the others are Good People. Though they will find themselves confronted with a number of difficult morally grey decisions, they would never dream of doing anything too awful to anybody.

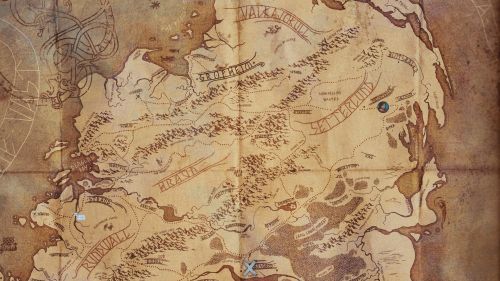

Lore junkies will also find themselves well served by the in-game map, which serves as the game's primary lore hub. Every location name links to a short paragraph that provides background info on the area, its history, its creatures, or the cultures that live there. These entries not only describe all the places you will visit during the game, but also many other unvisited locations that flesh out the setting (a wise move, considering that the game has been planned as the first part of a trilogy). Unfortunately, while I am generally in favour of packing as much optional lore into a game as you can muster, in this case I am forced to wonder if this was truly a wise use of Stoic's writing resources. The Banner Saga's dialogue, by no means an unimportant aspect of the game, ranges in quality between passable and awful. The writers have clearly paid heed to the fact that audiences do not want their fantasy heroes to speak ye owlde yngeliske anymore, but they seem to have overcorrected a bit. Most characters – and especially the Varl – sound like 21st century community theatre players putting on an improvised production of “Beowulf in New York.” I can see the logic behind that decision; making the characters sound “just like normal people” appeals to empathetically atrophied casual players while also saving money on writers who can actually create and maintain a distinctive way of speaking. However, in execution it comes across as a noteworthy flaw, a regrettable concession that hampers an otherwise coherent effort at creating a unique identity for the setting.

The game also offers an ample amount of second person narration to describe battles scenes and general movement (the art in dialogues is mostly static) and to present the player with decisions and random events on the road. The narration does not use as many modern mannerisms as the dialogue, though it often struggles in its efforts to sound like high prose. Still, if you can tolerate monstrous similes like “terror sweeps over the caravan like a pox,” you will find the narration to be perfectly serviceable.

Unfortunately, The Banner Saga is, at its heart, a mobile game. This is rarely noticeable during gameplay, since the UI is well designed and scales very nicely to desktop resolutions. There is, however, one simple, stupid flaw that stands out. Most RPGs present multiple lines of dialogue at once while a character speaks – for example, by showing a dialogue window. Other games show dialogue in speech bubbles or scrolling past. The Banner Saga, on the other hand, presents only a tiny snippet of dialogue at a time and forces you to constantly keep clicking to keep reading. A character may launch into a lengthy monologue on the secret fate of all life, and the game will present this speech line by line, immaculately chopped up into thin horizontal slices that stretch across the very bottom of the screen. Meanwhile, 95% of the screen space is reserved to a static image of the speaking character standing around and generally looking elegantly inexpressive. The game also likes to present curt exchanges between characters, and it does not automatically advance the dialogue (likely because there is usually no voice acting to dictate the pace). Thus, you read a five-word line of dialogue – “Hey, how are you doing?” –, hit the space bar, read a six word line – “I'm fine, but thanks for asking!” –, hit the space bar, and so on and so forth. This kind of choppy reading experience does not do the flow of dialogue any favours; in fact, it only draws more attention to the general blandness of the dialogues.

The Art of Choice and Consequence

Thankfully, skipping through dialogue lines is not the greatest gameplay challenge that The Banner Saga has to offer. In fact, the game has been heavily marketed as a multifaceted choice & consequence experience, redefining the classic industry paradigm of “the chosen one must choose” for a new generation of gamers. Let me quote directly from the official website: “Every decision you make in travel, conversation and combat has a meaningful effect on the outcome as your story unfolds.” Does that sound appealing to you? As usual, it is all a miserable pack of lies. What the game really offers is a strange combination between a very linear story and an extensive C&C system; this system relies largely on minor gameplay adjustments while manipulating the player with the threat of harsher consequences. And actually, this works out rather well.

To understand how consequences are implemented in TBS, one must first consider its save game system. The Banner Saga uses a system that only saves at specific checkpoints. There is one save slot for “minor checkpoints”, which is overwritten immediately after every important decision and battle, as well as when you quit the game. There are also multiple permanent save files for “major checkpoints”, which only occur occasionally. At the end of my playthrough, these major saves were between 5 minutes and one hour apart. It is possible to be faced with a tough decision and immediately discover that you made the wrong choice, only to realize that the game has just overridden your most recent save game and you would have to replay three long battles to be able to make a different choice. Choices can also have delayed consequences that may only appear one, two, or, in one case, a full ten hours after they were made. Anybody who has experience with different types of RPG may see a potential problem with this implementation: on the one hand, you have a highly linear story-driven game that constantly propels you forward along the path laid out by the developers. On the other, you have the promise of “meaningful” choices and consequences in a war torn world, which could – and, by all rights, should – include a lot of really, really bad things happening to you if you are being stupid.. How can the consequences be meaningful if the story is so linear? Can a story-driven RPG really afford to punish its players with long-term “bad” consequences that might force them to restart a ten hour old save game and play through the same content again? Why would the developer choose such a system for their game?

After close inspection, I can attest that Stoic's C&C system is quite cunningly implemented. Let us start with what would normally be the worst consequence of them all: you lose a battle against a horde of merciless enemies. Your heroes all fall unconscious on the battle field, and all hope is lost. What happens now? Reload to last save? That would be the bland, safe choice, allowing you to simply redo the battle until you get it right and can reap the rewards of victory. So, no, that is not what happens. Instead, a text window pops up and tells you how you got saved. Usually, some of your nameless supporting troops rushed to your aid and hurtled themselves onto the spears of your enemies, thus paying the ultimate price in the service of a smooth gameplay experience. Rarely, one of your less important companions made a heroic sacrifice, forever removing himself from your party roster in the process. Sometimes you wake up, battered and defeated, without really knowing what happened. Much e-blood has already been spilled over this mechanic; many of the game's harshest critics absolutely abhor the fact that it is (almost) impossible to get a game over screen from a party wipe. Other, more tolerant and progressive minds have come to appreciate the advantages of this implementation.

The Banner Saga has, fundamentally, six different means of punishing and rewarding the player for gameplay choices: Renown gains, item rewards, morale modifiers, changes to the amount of civilians and fighters following you, temporary loss of heroes, and permanent loss of heroes. Those are quite a lot of moving parts, but they are balanced surprisingly well against each other. The most important variable is Renown, which acts both as the party's shared xp pool and as the game's sole currency. Every time you gain Renown for your group (usually by killing enemies), you can decide to level up one of your heroes, buy an item for the group, or buy food for your entourage of faceless fighters and civilians. All three investments can improve your combat capability, which in turn makes it easier to earn more Renown in later battles. However, there are major differences between the investments that can make it difficult to decide on an optimal path. Levelling up a fighter makes them stronger, but becomes progressively more expensive as they increase in level. Furthermore, a character will only qualify for a level up once they have killed a certain amount of enemies; a weak group member who keeps getting knocked out at the start of battle cannot be pumped up to greatness with your Renown. Levelling also only affects that specific character – if you lose them, temporarily or permanently, the entire investment will become useless to you. On the other hand, buying an item gives you access to a major stat boost that can be freely equipped and unequipped on different characters. Here the game presents a different type of hurdle: store inventories are randomly generated, making it possible to never find anything good to purchase. You can also find very powerful items during your travels that can potentially make your store bought items mostly or completely redundant. It is quite easy to gauge which purchases are worth making if you are on your second or third playthrough, or if you are the kind of fool who cheats themselves out of a very fine gameplay experience by using a walkthrough. During my first playthrough, playing blindly, I constantly found myself fretting whether a store purchase or a level up would be the better investment. Sometimes I made a truly idiotic choice without realizing it until much later.

The final use of Renown is to purchase supplies that prevent your group from starving. At first blush, there is a bit of a problem with this mechanic, because you cannot actually lose your game due to starvation. You can theoretically get by just fine never buying any supplies, marching your entourage of bright-eyed peasants into the wilderness, and then watching them die a slow, horrible death while your heroes march onward unfazed and spend all their savings on level-ups and magic glitterdust. The game is not prepared for this “special” kind of player attitude and will consequently exhibit some rather odd behaviour. For instance, you might run into an event where 50 of your civilians go missing (old number: 0, new number: 0), and only 20 come back. The tragedy! The horror! You now have 20 civilians. This implementation has been sensibly criticised as a major oversight in the game's design, effectively turning a major tragedy (the total wipeout of the people you are meant to protect) into a mere gameplay nuisance.

However, starvation will also cause you to suffer a “morale loss”, which means that the combat capabilities of all your characters are decreased until you can cheer them up again. Furthermore, large battles will generally be more difficult due to the total lack of backup. Since almost every battle offers a second, optional follow-up engagement that rewards good players with extra Renown, you really want to be as strong as possible when you enter these battles. This is especially true because heroes that go down in battle can be “wounded” (i.e. badly debuffed) for several days of in-game time, potentially forcing your strongest fighters to sit out the next two or three major engagements. Thus, allowing your troops to starve is a terrible idea in terms of maximizing your gameplay performance. Lowering the difficulty cannot be used to easily circumvent this problem either, because Renown rewards also increase with difficulty. This is not enough to make the game easier on Hard mode than on Normal, because Hard has more and tougher enemies per battle; still, the increased renown rewards give you more build flexibility, which should dissuade you from lowering the difficulty unless you are encountering serious problems. Generally speaking, starvation only becomes an issue when the game wants you to be very short on supplies and, on top of that, you make a bad decision to invest your spare Renown in items or level ups instead. In that case, the player is punished, not just by lowered combat performance, but also by being forced through these silly sections of “lead a troop of bickering refugees that has zero people in it”. This is an immensely stupid immersion breaker that absolutely should not be in the game; still, it can be avoided by playing sensibly.

The idea of playing sensibly is key in The Banner Saga; since you cannot reload, every decision needs to be carefully weighed before you take it. And since every possible type of reward ultimately influences your combat experience, even the choices with small and trivial consequences will strengthen or weaken your heroes in the long term. These choices are usually presented through text windows that pop up during your travels, asking you to make decisions about whether the peasants or the fighters get the bigger share of your met supply (affecting morale), whether you take in a new group of peasants who might be criminals (and steal your items), how you resolve matters of justice among your group, or how you choose to scout a particularly dangerous area. Overall, the game offers an intricate mix of consequences to your actions; while most of the decisions reward being cautious, friendly, and attentive to details, you will also frequently come across cases that reward boldness, paranoia, or dishonesty instead. Sometimes you will run into situations where you know that somebody is lying to you, but you have no means of figuring out the truth; in those cases, you can stumble head first into failure without really doing anything “wrong”. I am rather fond of this implementation; it offers a measure of realistic unpredictability while still usually rewarding a methodical, well considered approach to problem solving.

This unpredictability is probably the system's greatest strength, as it infuses your decisions with a feeling of gravity. Early on, you are presented with a surprise death within your group. It is not immediately clear if you could have prevented it (no, you could not), but this death clearly communicates that even major characters can die at any moment, and that you might have to struggle to keep them safe. This actually bears out during the course of the game; sometimes as part of a fairly obvious “risk this person's life or save them?” decision, othertimes as the result of losing a crucial story battle, and yet more rarely as the delayed consequence of a seemingly minor decision you made hours ago. The story does, of course, still move forward in linear fashion, no matter what happens, and the NPCs' reactions to major deaths are generally limited to the immediate aftermath of the death. Your party roster is also large enough that all the optional deaths combined will not prevent you from reaching one of the (only very mildly different) endings – out of the 20+ available followers, there are six people (exactly one full group) whom you can always keep alive. However, it is absolutely possible to lose a max-level, well equipped core party member – and thereby a major investment of precious Renown – by making a single careless decision. This makes these deaths important enough to be taken very seriously, even if the storytelling is barely affected by them.

It is understandable why people might be extremely frustrated by this kind of consequence system, especially when it is not clearly communicated that a specific action might result in a death. I know that many RPG players strive towards a “perfect playthrough” and consider saving before every decision an essential part of their gaming experience. Others have no problem with harsh and permanent consequences, as long as they face a “fair challenge” where all the rules and major variables are laid open – or are, at the very least, solidly predictable – from the start. The Banner Saga is not likely to offer a satisfying experience to either of these types of player; it is a game for people who can tolerate, or even enjoy having to make irreversible choices without knowing how grave the consequences of their decision might be. I would describe this system as “immersive C&C”; the primary effect of this implementation is to create the impression of a realistically unpredictable world, where the difference between major and minor decisions cannot always be clearly seen. This is not “full” C&C; it does not offer a system of complex intertwining choices, and it does not offer any sort of non-linear or “emergent” gameplay. However, the consequences that it does offer are sufficiently meaningful and varied to keep the player engaged while leading him through a well told pre-defined story. It is a mixture that works very well in practice and keeps players both actively and passively engaged in their party's progress; this, I believe, is more than you can say for most other RPGs on the market today.

Viking Chess

A good battle system is well balanced. If a system is not balanced, then its designers have wasted time on coding options that are not worth using, on accommodating strategies that will never be efficient or appropriate, and on crafting animations and visual effects that most users will never see. Balanced battle systems offer a selection of development choices whose utility can change in the short term (depending on the circumstances of a given engagement) but roughly equals out in the long term. Unbalanced games offer clearly superior strategies that, once discovered, serve to greatly homogenize gameplay and character development. This approach is particularly accommodating to the dumb and the lazy – to those who would rather “just play” than to waste time with considering multiple approaches and choices. A good battle system is also mature and complete. It is immensely frustrating to discover that a carefully developed combat strategy has been based on incorrect descriptions or hidden bugs; it is yet more frustrating to discover that your well-honed character designs have been diminished or outright broken because the developer decided to push out a major rebalance patch in the middle of your playthrough.

The Banner Saga has a good battle system. Before the game's release, the system was tested in a multiplayer Free-to-Play game – The Banner Saga: Factions – which was released a full year before the single player game. Being able to study their players in a competitive environment provided Stoic with ample opportunities to discover the weaknesses of their systems design; the result has been a highly polished battle system that feels well thought out and fully coherent. That is not to say that this system is uncontroversial; in fact, it is probably the most hotly debated aspect of the game.

On the surface, combat in The Banner Saga looks quite harmless and traditional; you select up to six units to take into battle, equip them with stat boosting items, pre-position them on a battle map with a square grid, and then engage in turn based combat against your enemies, using melee weapons, ranged weapons, and magic. However, a closer look reveals that nearly every aspect of the design is implemented in a very non-traditional manner. When you select your units for battle, you also determine their action order in combat; the first unit drafted into the active party will also act first, the second unit second, and so forth. There is no initiative stat, nor any way to delay a friendly unit's turn in combat (at least not until you gain access to a special and very limited ability in the late game). Thus, your heroes' move order is almost exclusively determined during party selection. The items you can equip on your heroes are not weapons or armor, but magical talismans; these talismans are level restricted, so that a level 3 character can only carry a level 1 to 3 magical item. The pre-positioning areas often take unusual shapes; for example, you might be forced to carefully distribute your party in a diagonal line across the battlefield. The actual damage mechanics are also surprisingly complex; one particularly perplexing design choice is the Strength statistic, which not only determines a character's damage output, but also serves as their health pool. Thus, a combatant's damage dealing capability is directly proportional to their current health. Finally, the turn order between the friendly and enemy team alternates for every turn; you start with the first combatant on your team, then the enemy responds with his first character, and so on and so forth. If the enemy team has twelve members (about the maximum amount that you might encounter on Hard difficulty) and your team has six members, then the enemy will need twelve turns to move his entire party, while you will only need six turns; thus, every one of your characters will be able to move twice before the enemy has cycled through his group. Conversely, when there are only two enemies left, they will be able to move three times as fast as your group of six, potentially dealing serious damage despite being heavily outnumbered. This strict apportionment of turns only stops when one group has been reduced to a single member. That event triggers “pillage mode”, which is designed to let you swiftly bring about an inevitable conclusion without having to waste your time alternating turns; the winning party gets to move every member of their group once, and their enemy can move his single combatant once as well.

It is easy to see why players might respond badly to this kind of implementation; it has little to do with real world battles. In a game whose art and narrative design trade so heavily on atmosphere and immersion, it can seem very odd to be dropped into a turn based arena whose rules are designed towards creating complex challenges rather than emulating real life situations. And yet, it seems to me that these two disparate areas of the game are absolutely reliant upon each other to create a good, entertaining, and complete gameplay experience. Much as I like The Banner Saga's C&C elements, I will never find the basic task of “click one of three options and see what happens” to be as intellectually engaging as the challenge of weighing up five or six different possible combat moves in a single turn of battle. On the other hand, while the game's combat is certainly rich and interesting, it suffers from a distinct lack of enemy variety as well as from offering slightly too few unique setpieces; there are only so many battles I can fight against a big blob of the game's three main types of enemy – Small Dredge, Big Dredge, and Ranged Dredge – before my brain wants to be confronted with a genuinely novel situation again. The game also offers a decent variety of human enemies, but the nature of the plot makes encounters with them less common than they should be.

Indeed, this lack of variety in scenarios and enemy types is the combat system's only real flaw; its other elements are tightly and intelligently constructed. Consider, for instance, the implications of the health system for the role of a character in battle. In the stereotypical modern fantasy RPG (i.e. Dragon Age: Inquisition or Pillars of Eternity), you can find a more or less clear distinction between the classic MMO roles of tank, damage dealer, and healer. You want enemies to keep beating up the resistant character (the tank), the damage dealers trying to kill the enemy from a position of relative safety, and the healers keeping everybody alive. When health and damage output are combined into a single stat, this distinction becomes untenable. Any character with high Strength can be expected to deal high damage; they should stay at full health for as long as possible instead of wading into the middle of combat for the express purpose of being whaled on by every enemy. Since the Strength stat is thus pulling double duty in the game, being able to heal your characters would be immensely powerful; consequently, the player is given no access to in-combat healing at all. The fundamental challenge of The Banner Saga's combat is to deal as much damage as possible while remaining at full health for as long as possible. You will have access to a few archers and a mage, but that will not be enough to avoid swift melee attackers or enemy archers in the rather small arenas. What to do?

The most basic answer is “wear armor”. Within the terms of this combat system, armor acts like a secondary health pool that does not improve damage and can absorb blows that would otherwise diminish a character's health. A character can choose to attack either his opponent's health or his armor; directly attacking health is always possible, but the amount of damage is reduced by the amount of armor the opponent is currently wearing; in a worst case scenario, you will have a 20% chance of dealing 1 health damage with an attack against an enemy who may have 17 or 18 health. This would not be a wise use of your resources. Alternatively, you can attack the armor directly, dealing armor damage. The amount of armor a character has is measured as a pool of points, just like health; if you have 10 armor, you can take up to 10 armor damage. Losing armor value also causes you to lose damage reduction against attacks that target health. Thus, it is important for an attacker to calculate the correct moment when it is time to stop attacking armor and start attacking health instead. Since the same types of enemy can have varying amounts of base health and armor (and may have special abilities to regenerate their armor), you will have to re-evaluate your enemies' stats for every encounter. Thankfully, these stats are fully laid open; you can simply click on an enemy to learn everything about them. When you choose to attack an opponent, the game will allow you to preview the damage you can deal to their health or their armor in clear and absolute numbers; there is almost no damage randomization apart from those cases where you choose to attack the health of a heavily armored enemy and have less than 100% chance to hit. Because armor is so powerful, it is implemented as a character stat, and not as a function of itemization; if you want to be well-protected, you need to spec your character for it.

Do not be fooled into thinking that this trivializes combat. The alternating initiative order constantly changes whenever any unit leaves the battle; thus, you always need to carefully consider how your own moves interlink with enemy moves, and how killing an enemy will change the rhythm of combat. Yes, killing an enemy can be a bad move in The Banner Saga; leave them at 1 Strength and they will do very little damage while taking up a space in the queue that might otherwise be used by an elite monster. Let us fully ignore the “realism” of this design choice; this is not the yardstick by which this system needs to be measured. Instead, we should examine whether this mechanic is conducive to good gameplay. Are there risks in keeping weak enemies alive? Yes. Some enemies will retreat and summon reinforcements as soon as they reach low Strength. If you do not have an archer or a well-positioned mobile melee attacker coming up in the turn order (which can, of course, be anticipated through sensible planning), you will likely be unable to stop the summoning and end up in a worse position than if you had simply killed the enemy swiftly and decisively. Enemies can also use special abilities to greatly hamper you in combat; killing a low-Strength enemy before he can use his special is a much better choice than leaving him alive to debuff your troops or to violently push them out of position. Troops can also be specialized to destroy armor; this is particularly insidious with low-Strength troops, who may pose no threat to your troops' own Strength score, but who can tear off your armor and expose you to a massive blow from another, high-Strength enemy.

These specializations are handled through a simple, but meaningful stat system that manages to be reasonably well balanced to boot. Merging health and damage values has, at least for this game, proven to be a highly effective way at providing multiple sensible variations within character design. A character has five main stats: Strength, the core defensive and offensive stat, Armor, the dedicated defensive stat, Break, the dedicated anti-armor stat, Willpower (or “WP”), the pool for performing special feats in battle, and Exertion, the limit on how much Willpower a unit can spend in a turn. These stats are closely interlinked; Strength targets enemy Strength, but it does nothing against Armor. Armor protects your Strength and allows you to take hits without losing your damage dealing potential. Break allows you set up enemies to take heavier blows and decrease their damage potential more quickly; have a high-Break character attack a target's Armor, follow it up with an attack against Strength by a high-Strength character, and you will have done much more damage than if you had simply performed two Strength attacks. If you do not have a Break attacker coming up in the queue, if your melee attacker is just a little bit too far away from a high priority target, or if your Health and Break are low and you can do basically nothing with your standard attacks, it is time to use your Willpower. You can invest it straight up into dealing more damage: spend three WP to amplify a standard attack, and you deal three more Break or Health damage. This is assuming you have three Exertion; if you have only one Exertion, you can only spend one point per turn. You can use also use your Willpower to move farther; one WP, one more square. Or you can use it to fuel a special attack that can push an enemy away, destroy his armor, increase your own defenses, or hit multiple enemies in an area.

The amount of points you can invest into each stat is limited by a character's class; thus, the classes provide some differentiation between builds with strong defensive capabilities (with a higher limit on the Armor stat and perhaps a defensive special ability) and stronger offensive capabilities (with an offensive special attack and higher limits on the Break and Exertion stats). This system confines ranged units into a damage dealing role; they simply do not have the Strength or the Armor to drop into a defensive melee position on demand. Melee units are generally more flexible; it is entirely possible to take a character with a high Armor limit and a defensive special and spec them for Break and Exertion, thereby creating a well-rounded and viable build. Health is generally useful for every type of character.

Knowing when to invest how much Willpower into which action is a science in itself, at least if you are playing on Hard mode. Even ranged characters – the closest the game has to a pure damage dealing type of character – need to carefully adjust their position to accommodate their short attack ranges, their weak defenses, and the peculiar limitations of their special attacks. For instance, one of the classes has a special attack that deals heavy damage to all characters (friend or foe) in a line, but only within a short range; you need to be on the lookout for opportunities to use this ability, and you should be ready to spend some of your Willpower to get yourself into position if need be. However, if you spend 1 WP on extending your movement range, you will still need to invest at least another 1 WP to fuel your special attack; you can only make both of these investments in the same turn if your Exertion is at least 2, otherwise you will need to wait another turn. You can also regenerate Willpower during combat through items and special actions.

Most importantly, you gain a single point of WP for every enemy unit you kill. These points are earned for the entire team and can be freely granted to the unit who can, in your humble opinion, make the best use of it. This mechanic provides you with yet another reason not to let weakened enemies stick around. However, it also slightly diminishes the value of a character's Willpower stat – particularly on harder modes, where the increased amount of enemies also means that you earn more WP in battle relative to your starting pool. This is the rare case in which the game's stat balance works better on Normal mode; nonetheless, Normal is generally so unchallenging that it is hard to recommend to anybody but the filthiest of casual players.

Melee combat adds yet another layer of complexity; the system makes do without any sort of engagement mechanic and instead focusses on area denial through sheer size. Friendly and enemy units are either one square in size (1x1) or four squares (2x2); in other words, they are either human-sized or Varl-sized. The battlefields are usually quite small – around 15x15 squares in size – so a party of six Varl-sized units will have to move around very carefully to avoid blocking each other off. Put two units one square apart from each other, and only human-sized units will be able to move between them; surround an enemy unit with Varl units on two sides, and your other melee attackers will have to take a long detour around the Varl to reach the enemy. However, the enemy will then also have a harder time reaching your ranged attackers, who can take reasonably safe positions behind the Varl. Sometimes, a unit's class can be the deciding factor; in addition to a relatively weak passive ability, each class also receives at least one special active ability. These abilities, when used in the right situation, can make a major impact on the flow of battle. Some attacks may target all the enemies surrounding a unit (good when fighting smaller enemies), while others can give all friendly units within attack range of a selected enemy an instant free attack (very good if you have brought a party of ranged attackers and small melee units). There are also class abilities that can change the dynamics of the battlefield in a long-term fashion, for instance by making minor adjustments to your party's turn order. This system is further enriched by enemy weaknesses like “Splinter”, which causes armored enemy units to deal close-range shrapnel damage to their own troops when they take armor damage, and a number of very strong enemy special attacks; thus, you are forced to select the proper mixture of offensive and defensive positioning for your units. In practice, all of these considerations are conducive to a unique brand of challenging gameplay that rewards tactical intelligence and foresight.

Unfortunately, the AI is not entirely up to the task of taking full advantage of this system; while it is reasonably smart in positioning itself and going after weaker targets when it is appropriate, they often use their special attacks in rather questionable ways, occasionally even dealing more damage to themselves than to their opponents. The combat system is sufficiently complex and flexible that even a dumb AI can cause significant trouble to the player; still, one cannot help but wonder what might have been possible if we were playing against a genuinely intelligent opponent.

Parting Remarks

The Banner Saga is an immensely unique, and, by no coincidence, immensely good game that combines great artistic design and robust C&C mechanics with a highly entertaining and deceptively complex battle system. The Banner Saga has only a few outright flaws; the shoddy dialogues and the constant need to click-click-click through them line by line are a blemish on an otherwise engaging narrative. Moreover, the startling lack of enemy variety and the relatively dumb AI keep the battle system from realizing its potential for true tactical greatness. The game's system of choices and consequences also has far less of an impact on the story than Stoic's PR department has been trying to claim; nonetheless, it still offers an engaging and immersive range of decisions that will directly influence your battle performance and can occasionally result in major character deaths.

I suspect that The Banner Saga will always be the subject of great controversy; it has a kind of self-assured swagger, flaunting all of its little weirdnesses and weaknesses without making much of an effort to look like a typical tactical cRPG or a typical casual story game. The game features heaps upon heaps of idiosyncratic gameplay systems, like the strange combination of a broad C&C system with a fully pre-determined linear story, the fact that you will rarely if ever be able to see a "game over" screen, the "sit back and immerse yourself" approach to map travel, and a whole slew of novel and deeply unrealistic combat mechanics. You may choose to accept or reject these mechanics according to your personal preferences; all I can tell you is that all of these elements stand in the service of a fully coherent and extremely tightly designed gameplay experience that I deeply enjoyed playing through.