RPG Codex Retrospective Review: Pillars of Eternity Revisited

RPG Codex Retrospective Review: Pillars of Eternity Revisited

Codex Review - posted by Infinitron on Tue 4 July 2017, 20:09:19

Tags: Obsidian Entertainment; Pillars of Eternity; Pillars of Eternity: The White March[Review by Grunker]

It is a cruel friend, nostalgia. It initially aided me as I outgrew my childhood, letting me hold on to at least some of the love I once had for this cartoon or that toy.

Then, as critical awareness evolved with age, the same nostalgia that once tinted my proverbial glasses with a rose hue reminded me that all I had left for many of the things I used to love was exactly that: nostalgic reverence. There was no legitimate reason to enjoy so much of what I once cherished.

This is especially pronounced when it comes to video games. Nostalgia was the last remaining barrier between cynical rejection and adoration for several games that I used to like. Neverwinter Nights, for example, plays poorly and the story is a cavalcade of the worst fantasy clichés, yet it takes itself seriously. I also recently replayed the original Knights of the Old Republic, which was a thoroughly disappointing experience. The gameplay is an awkward abomination of over-the-shoulder shooting and tactical RPG. The writing is so childishly blunt it has Sith characters laughing maniacally with voice acting borrowed straight from saturday morning cartoons as they commit everything from schoolboy pranks to vile acts of torture.

Other games that still hold up as a whole show cracks where none were visible before. The combat of the Might & Magic series has very little interesting going on and rarely takes advantage of the game's luxurious spell selection. Westwood's 'Lands of Lore' is pretty, but otherwise the game pales when compared to other, better games in its genre. One such better game is Wizardry 8, but excepting the most fanatic fans, anyone who has played it will admit that this old-school titan has an excessive amount of fights that take needlessly long to complete, making an otherwise excellent game a veritable slog even as early as the midgame.

Though it amounts to heresy around these parts, even mighty Fallout has blemishes: simplistic combat and a shallow, unbalanced character system being the worst.

The part of adulthood that is harshest towards enjoyment of video games is developing the curiosity to sample some actual great literature and watch a few of the choicest films. Exposure to actual quality might bring you to the realization that the games industry is stuck in a juvenile rut, and has been since the inception of the medium. These days, I find that nearly no piece of entertainment that I used to enjoy as a kid can withstand the full thrust of adult cynicism.

Except, perhaps, the Infinity Engine games.

That Bridge Crossing From Tomorrow to Yesterday

They are not perfect games - far from it - and I cannot deny a personal bias here, in that so many of the games' fundamentals appeal to my tastes specifically. Excepting Planescape: Torment, none of them certainly constitute art in any sense of the word. But perhaps their innocent ambition to combine damned good gameplay with narratives that have little ambition besides facilitating frolicking adventures is precisely why they still hold up.

The first Baldur's Gate, for instance, takes you on what might be the closest video games have ever gotten to recreating the immaculate excitement of the earliest D&D adventure modules. All that is absent is starting the party at an inn. That part is delayed until an hour into the game, where you pick up Khalid and Jaheira, whose story around a table filled with character sheets, dice and empty coke cans would most certainly begin with the words "you're sitting in an inn. Gorion's ward enters."

In the same vein, Icewind Dale is a magnificent tour of the combat-heavy, almost wargame-like dungeon crawls of the eighties, seasoned with the long-forgotten craft of actual, evocative fantasy art and locales. People past the emotional age of 14 who look at Icewind Dale's artwork will feel a natural inclination to weep at how modern works of fantasy choose to depict their worlds.

If these images do not ignite your imagination, perhaps you also think the prequels had better lightsaber duels?

Bringing up the rear, Planescape: Torment has by far the weakest gameplay but the strongest story and one I was surprised to find, when I replayed it last year, holds up to the scrutiny of a critical adult, now well-versed in media that aspire to more than entertainment. Torment explores its themes proficiently, the story is constantly surprising and there is actual depth there: motifs integral to humanity that are worth discussing. Most of all though, it is wonderful; with some new marvel or impossible phenomena awaiting you on every area load.

The sequel to Baldur's Gate, 'Shadows of Amn', does what any great sequel to a good game should: damned near carbon copies the entirety of what works including graphics and audio resources, ramps up the stakes in the story, refines the writing and expands on the systems and gameplay already in place. It also starts to show the path that will ultimately doom BioWare's brand of RPGs, with a few of the companions acting like annoying and whiny teenagers in the middle of a world-shaking conflict. Mostly though, the experience holds up. Overall, the writing certainly matured from the almost non-writing of the original Baldur's Gate's side quests (siding with the druids on the grounds of aloe vera balm, anyone?). Irenicus is a strong villain, voiced by an even stronger actor in what is arguably the best performance of his career.

In all but Torment's case, the IE games' conceit of coupling modern RTS-like gameplay with the tactical, squad-based combat of traditional D&D succeeds completely, despite the concept being so at odds with itself. The games give you the frantic thrills of StarCraft's rushed micromanagement with greater input required per unit and the tactical control of a pause-button.

What might be the most direct predecessor to the Infinity Engine games bears mention here: without the unique ingenuity of 1992's 'Darklands', had Baldur's Gate's gameplay ever assumed the form it did? Maybe – but surely someone, somewhere at Black Isle or BioWare must have fired up Microprose's historical RPG and thought, "hey, this is pretty cool".

This style of gameplay, dubbed 'RTwP' (Real Time with Pause), was BioWare's attempt to bridge the tactical construct of yesterday's dungeon crawls with the, at the time, insanely popular top-down strategy gameplay of tomorrow, StarCraft having just been released. The mutated compromise they developed as a result is often criticized, but not for entirely respectful reasons. Most criticism boils down to the fact that there is little overlap between the people who enjoy the fast-paced, action-per-minute-driven battles of an RTS and the people who enjoy pondering endlessly over decisions in a turn-based game. For those strange creatures who do appreciate the mix, the Infinity Engine set the standards for everything that would follow. Add in some modern coding with modder DavidW's "Sword Coast Stratagems", which balances a few systems and makes the AI surprisingly sophisticated for an engine released in 2000, and the result is a combat experience iterated upon to near perfection, perhaps more so than any other game in computer RPG history.

What will probably be your first dragon fight in Shadows of Amn awaits you at the end of a major side quest with its own a score of subquests and a lengthy dungeon crawl.

Somehow, even the terribly outdated character system – "Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, 2nd edition" – with its poor balance and horrid lack of character customization options, has been gracefully woven into these games. The designers correctly chose to focus their efforts on AD&D's spell system, which might be the one part of the game worth preserving. Much of the actual enjoyment of an IE-game is pausing to set up a particularly devastating spell, then unpausing and controlling the positioning of your characters, adapting to the new state of the battlefield.

Systems & Sorcery

The character system is worth dwelling on as we start to delve into the IE games' spiritual descendant, Pillars of Eternity. (And no, we are not counting Dragon Age here, because despite an honest attempt from the first game, Dragon Age 2 and 3 made it quite clear that BioWare had no actual ambition of refining the formula, but rather meant to capitalize on nostalgia for the IE games).

Pillars of Eternity is nothing if not the story of how to rethink an iconic character system. In so many facets of its development, Pillars stays true to the IE formula: the combat controls are so similar only hardcore fans who have played the IE games multiple times can tell the difference. Graphically, the game interposes avatar sprites of characters on gorgeous 2D images. You have six party members who bark at each other and at you, and you have a completely open world map with smaller "point of interest" locations to visit, sometimes gated by story progression. Exploration is handled by "painting" a black background consisting of fog of war with your characters' line of sight as you move through the area. When you click on an non-party character, it brings up a dialogue screen with multiple, fully written-out lines of responses for you to choose between.

The character system on the other hand has undergone an overhaul so massive that any resemblance to the original remains almost symbolic. Yes, both systems are class-based, yes both systems have you level-up to gain new abilities and yes, there is even a remnant of the "Vancian" spell system in there, since spells are limited to daily castings – though even here, the system lacks the trademark D&D spell memorization.

To understand how and why Pillars of Eternity takes such an extensive departure from the genre's D&D origins, we must take a moment to discuss the character system of the IE games, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, 2nd edition, in more detail.

It is impossible to make a concise statement on the vision behind Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, because their simply was none. In the rulebook's foreword, creator Gary Gygax speaks of a creating a consistent framework for games, of adding uniformity to campaigns and of shedding the arbitrary distinctions so often present in rules systems at the time. He even speaks of the need for BALANCE™, which is ironic since it has made the Lead Designer of Pillars of Eternity, Josh Sawyer, so reviled by the same grognards who revere Gygax and who claim system design was perfected with AD&D.

Yet in the substance, Gygax' intro reads like a politician's glorious statement of intent before he inevitably breaks every campaign promise.

To start with, AD&D's biggest sin is that it is arbitrary in the most literal sense of the word: "based on random choice or personal whim, rather than any reason or system." The irony that Gygax himself mentions arbitrariness as a hazard to avoid in system design is completely baffling considering the fact that arbitrariness might well be considered the defining trait of AD&D.

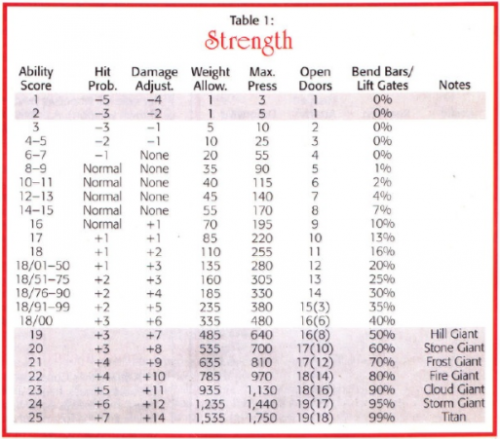

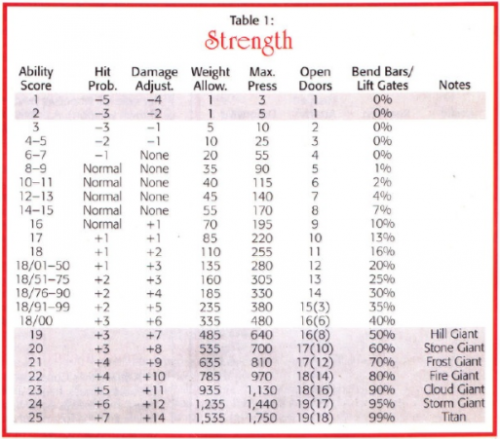

Why do all attributes go from 3 to 25 specifically? Why does Strength have a special 01-100 sub-attribute only if you are a specific class and only if you have a score of exactly 18? What is the reasoning behind the reversal of the to-hit roll, asking you to go backwards on the number line instead of forward? Why do Clerics only have access to seven spell levels while Wizards have access to nine? Why do you roll for hit points until level 10 at which point you gain minor, static increases? Why does a Ranger need 150,000 experience points to progress from level 8 to 9, while a Wizard needs 45,000? Why must an Illusionist have a minimum Dexterity of 16? Why do Clerics gain bonus spells for high Wisdom, while a Wizard gains no similar bonus for high Intelligence? Why is it easier to save against the same spell cast from a rod or wand rather than if a mage cast it? Why is the difficulty of resisting a spell based solely on the target's level and not on the caster's? Why are certain combinations of multi-classing restricted from certain races? Why does dual-classing work on an entirely separate system, and how do you forget everything you learned about shooting a bow and arrow because you decide after 10 years of rangering to pick up clericing? Why is there a specific attribute for "bending bars" and why is it handled by a percentile roll when "Open Doors" is not? Why do thieving-abilities work on a completely different, percentile-based system compared to other skills and class features?

Why, why, why, why, why?

"No no, I assure you, everything in this table was implemented with the utmost care to abstract reality and make for good gameplay." Riiiiiight.

The answer to all of these questions – the answer to almost any question regarding the system design of AD&D – is: "because the designer felt that is how it should be."

Or in more modern terms: for shits and giggles.

In addition, AD&D is actually a fairly simplistic system despite the "advanced" moniker. Most level-ups will result in a hit-point gain, perhaps a THAC0 increase (or decrease, depending on how you want to look at it) and little else, unless of course you happen to be casting spells, in which case you might be granted a couple of spell slots. How many times do you level up in the IE games, only to simply click "OK" and move on? Paradoxically, AD&D at once embodies this superficial simplicity yet is designed to be more convoluted than is actually necessary for the thin substance it represents.

I really only included this picture to hammer home the point that modern fantasy art ain't got shit on the 80's and 90's.

Most of the very best tactical cRPGs of the past are great despite the shackles of AD&D, not because of them. Of the AD&D games, the one praised the most for its character system is Wizardry 8, which offers a staggering range of classes, races and customization options, all of which are viable in the game. Yet this praise is also damning to AD&D, because Wizardry 8's system is so heavily modified you can barely recognize Dungeons & Dragons beneath it all.

Gary Gygax is worthy of respect for putting more narrative, context and adventure into what was once merely wargames. If not for him, we would have never experienced the wonder of roleplaying games backed by interesting and unique gameplay systems. The fact is, though, that AD&D is massively inferior to nearly every rules system that has followed it.

Which brings us to Pillars of Eternity.

This Ain't Tabletop No More

It was no surprise when Lead Designer Josh Sawyer admitted that lack of licensing was not the only reason that Pillars of Eternity would free itself from the chains of D&D. After all, the most fine-tuned version of D&D, the 3rd edition update 'Pathfinder', is based on an open license and completely free to use.

Rather, Sawyer's personal distaste of the system played a significant role.

The switch from D&D is the single-most impacting change that Pillars of Eternity makes to Ye Olde Infinity Engine, and as the original Kickstarter rolled out, it was an oft-cited reason to be skeptical of the game. I was among the skeptics since for all my dislike of AD&D I love the version of Dungeons & Dragons that followed it. This system, called "3.5" for short, is, despite its non-existing game balance, an incredibly fun sandbox in which to customize RPG characters and toy around with different builds. If you crave balance to the degree that Josh Sawyer does, D&D 3.5 and Pathfinder are kryptonite, but if you love having an infinite array of character customization options at your disposal, they just about represent the pinnacle of RPG design.

Josh Sawyer wanted something else. He wanted to finally bring RPGs fully into the digital realm. He insisted that tabletop and computer RPGs were so different that rules systems needed to be designed with the specific medium in mind. And he wanted what has made him infamous amongst the basement-dwelling, character sheet-loving "grognards" of the tabletop world: game balance.

Knowing that Sawyer was going to design a new system from the ground up was my main concern about Pillars. The open license version of D&D 3.5, available free for everyone to use, could have saved Obsidian and Sawyer a vast amount of effort. As Sawyer began posting development logs however, it became clear that he had a strong vision for RPG system design, and curiosity quickly substituted skepticism.

Clearly a man who understood the Infinity Engine, had extensive tabletop experience and a precise idea of how to evolve RPG design. The terrible dad jokes came with the territory.

Would Sawyer deliver a game with the core of the IE games intact but with their sole, lackluster component fixed?

In that case, count me in.

Le Petit Éternité

When I first finished Pillars of Eternity, it was with an odd sensation of disappointed near-fulfillment. Like I just eaten a fine meal seasoned with ash. Everything from the gameplay to the story showed infinite promise, but nothing quite delivered on the theoretical potential.

Very early in the development process, Lead Designer Josh Sawyer vocalized his dislike of total fail states in system design. Central to this dislike was a distaste for 'hard counters', like a fire elemental being completely immune to fire damage. For this reason, Sawyer also initially designed Pillars of Eternity's system with no misses, substituting them with "grazes" that dealt less damage. He also based his armor-system on gradual damage reduction rather than outright evasion. Furthermore, Sawyer announced his goal was to make every skill, talent and attribute of his system useful. Not necessarily equally good – but the intention was to make sure that there were no "traps" – abilities which were downright awful.

In theory, I lauded these goals, which were predictably criticized by grognards everywhere for being implicitly poor design. The grognardian criticism was based on the idea that there must be bad abilities and pitfalls in order for players to feel rewarded for building a good character. I certainly do not mind systems that do this – I am an avid Pathfinder player in my spare time, after all – but I also fail to see why it should be a general rule. With Pillars of Eternity, Sawyer was attempting to give the player a framework of classes and abilities that they could toy around with to their heart's content, safe in the knowledge that all combinations of assets in the system would at least provide some measure of functionality.

Cries of "OMG WHY IS STRENGTH IMPORTANT FOR A WIZARD" quickly rose as Sawyer laid out his plans to balance the classic attributes of an RPG. The criticism was that the system had been gamified to the point where it no longer abstracted reality, while Sawyer maintained that mechanics existed to play well and be balanced. Thus, every attribute should have something to offer every class.

On the surface, Sawyer reached his goals. Pillars of Eternity had plenty of customization options even on release. A multitude of talents, backgrounds and races with unique and spiffy racial traits made every character feel fairly unique. Due to the vast range of classes to choose between it certainly felt like you were diving into the best character customization since Neverwinter Nights 2 (which, incidentally, was also developed with Josh Sawyer as Lead Designer and, for all its faults, has the most expansive character customization of any computer RPG).

More than anything else, Sawyer drew inspiration from the 4th edition of Dungeons & Dragons, which many consider to be a failed experiment, but which Sawyer lauded for its game balance and uniformity. 4th edition compromised on the fundamental difference in feel between classes to provide "something to do" during combat for all classes, to do away with the "boring auto-attacks vs. exciting spellcasting"-feel that characterized fighting and spellcasting classes respectively in earlier editions of D&D.

Yeah so there's no dynamism or marvellous fantasy concept in this picture to pique your narrative interest and it looks like a cartoon, BUT ISN't IT COOL HOW THE SWORD IS LIKE A GIANT RAZOR-SAWBLADE THING AND YOU CAN TOTALLY PLAY A DRAGON. Sic transit gloria mundi.

In many ways, Pillars of Eternity succeeded completely in shedding itself of the problems of older fantasy character systems while maintaining distance from some of the aspects of 4th edition that received the harshest criticism. Your fighter, though a simpler unit to control than your mage, did not just stand there and "auto-attack", but he wasn't just a melee spellcaster either - rather, he had a range of passive abilities which heavily influenced the outcome of fights. Paladins had less of these implicit battlefield-controlling options but had an array of spell-like buffs at their disposal.

The careful balancing and uniformity of Pillars' system came at a steep price, however: the changes you made to a character on creation and level up felt completely minuscule at the game's launch. A huge part of this was thanks to the universality of the abilities in the system and the fairly minor impact of each system asset.

Since the Mass Charm that worked so well for you in the last 20 encounters would work equally as well in the next 20, switching tactics was, for the vast majority of encounters, reduced to a matter of style. In dire cases, even gaining access to high levels of spells would yield no excitement, as the level 2 immobilizing spell you had grown so fond of would suit you just as well at level 10. Often, your character did not grow into new possibilities, unlocking doors that were formerly closed to her, but rather got additional, redundant choices.

This was probably the biggest weakness Pillars of Eternity dealt with at launch. And it was, despite my reluctance to award the AD&D grognards with a win here, precisely because the game did not have the necessary encounter variety to make up for the lack of hard counters. While I personally do not share the narrow-minded pessimism that hard counters are a necessity for tactical variety in combat, the simple fact is that Pillars of Eternity provided no alternative to make up for their absence. As such, the lack of immunities and complete fail states led to the problem that once you found any sort of working strategy, finishing the game was entirely trivial.

Even so, Pillars of Eternity's combat showed great promise. The Path of the Damned difficulty setting was like an expanded Sword Coast Stratagems mod, with meticulously placed monsters, additional enemies and increased battlefield complexity. Specifically, difficulty settings in Pillars of Eternity have different monsters appearing in the same encounters, but Path of the Damned rolls them all into the same encounter, increasing difficulty substantially. In addition, monsters are given a bump to all stats, as well as an Accuracy and Defense bonus on top. Even if the lack of competent AI and functional monster defenses really hurt the execution of Path of the Damned at launch, the principle of the design and the actual variety between difficulty levels, as opposed to simple hit point bumps, was something seen all too rarely in RPGs and games in general.

Sawyer also turned the extremely fast (even faster with the 'Haste' spell) and frantic combat of the IE games into a slower, more methodical beast by severely limiting the movement speed of characters and with the inclusion of the Engagement system that punished player and enemy alike for moving indiscriminately across the battlefield. This choice was controversial among dedicated fans of the original Infinity Engine games, as it further removed Pillars from its Real Time Strategy roots and made trash fights, which were no issue in the IE games, a slog to wade through. On the flip side, the deceleration also made movement and positioning a much more engaging and challenging part of the game.

The theory of a fantastic game was there, the basic structure of something greater than we currently had. If the problem was that lack of monster defenses and AI made otherwise great content trivial, maybe there was light at the end of the tunnel?

Halfway Between Inspired Originality and Tired Cliché is Nowhere at All

The game's setting, I suspect, was doomed to cause trouble. The player-base demanded a classic fantasy world, Obsidian wanted to deliver something that, like Torment, was intellectually challenging and Sawyer, being a history buff, wanted to ground it all historical realism.

Like a dish cooked with too many exotic spices causing the final product to be a tasteless mish-mash, the result was that Pillars felt surprisingly bland despite the multitude of interesting things going on. Pillars' themes of colonialism and religion seemed compelling and spoke of more mature ambitions than the average RPG, but it quickly became apparant that the execution left a lot to be desired.

Obsidian has handled the limitation of having to deliver an engrossing story within an established world well enough before: by using their writing to deconstruct the setting as in 'Knights of the Old Republic: The Sith Lords' or, as in Neverwinter Nights 2's expansion 'Mask of the Betrayer', by simply choosing an incredibly exotic part of the stock fantasy setting to excuse their trademark, eccentric writing. Unfortunately, Pillars' noble aspirations to include serious and stimulating writing clashed hard against the shackles of classic fantasy tropes. The core of Pillars of Eternity – the idea that souls are a tangible, world-defining fact – feels tacky and contrived for most of the game, and it is difficult to accept hard historicism delivered through the teeth of humanoid fire elementals and other loony fantasy characters that do not cause regular townsfolk to bat an eyelid.

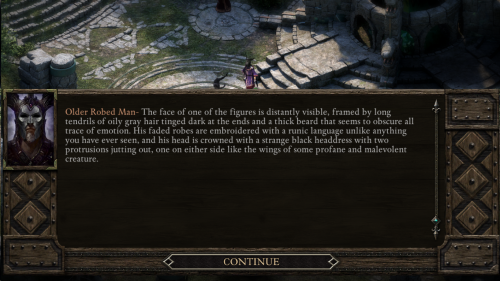

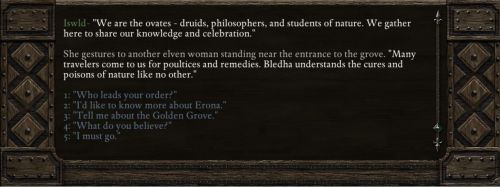

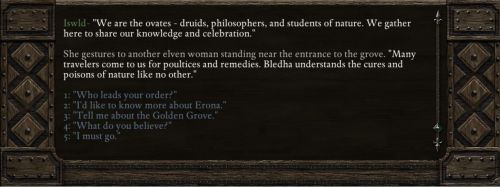

The main problem with the setting is that Pillars of Eternity is so concerned with delivering its heavy lore that most characters do not act like characters but rather deliver their lines much like walking Wikipedia articles. After playing Pillars of Eternity for a while, you start to dread clicking the 'Talk' icon hovering over random NPCs, because all too often, initiating dialogue is functionally identical to clicking hyperlinks on everyone's favorite, digital encyclopedia.

"Dump your descriptive text on me, please, mr. Random NPC." Real people do not talk like this. (Image blatantly stolen from RPG Codex user CptMace without permission.)

The odd part is that the lore of Pillars is deliberate genuinely different than that of most fantasy worlds and at times even fascinating. What makes it all fall apart is not the substance, but the delivery. Immersion in deep lore comes through context and meaning, not by a look-up in the in game character-equivalent of a campaign-setting book.

Our fault for asking Pallegina about her work. Apparantly it can't be explained without the use of some mystical language that seems to be a mix between English, Italian and gibberish. (Once again, the image was stolen from user CptMace in an act of intellectual theft most vile.)

A good contrast to the majority of the core game's writing is Durance. This gruff, sullen priest companion is an aggressive spin on Planescape: Torment's more reclined, crisis-of-faith character 'Dak’kon'. Durance exemplifies how to handle lore dumps in an engaging way. He is a passionate, engaged bullshitter whose story tells us everything about the Dyrwood without resorting to massive blocks of text with nothing but exposition. Instead of telling us literal facts about the setting like "Dyrwood is very independent and because of all the hardships its inhabitants are very driven and nationalist folk", we implicitly learn the lore of the region through Durance's teachings and the tall tales he tells. The stories Durance tells are themselves engaing; the lore we pick up on the way is merely incidental.

While we may be inclined to be lenient towards Pillars' task here – explaining such a vast body of lore through short bursts of text – consider how Planescape: Torment had a much more confusing, lore-heavy world, yet most of what we know of Sigil, we are told through its characters acting, behaving and being themselves. Our knowledge of the Mercykillers is not derived from Vhailor's 6-page rant about the structure of the order, but through debating its principles with him. We know of the Sensates not because we read the Codex entry in our journal, but because we go to the Sensorium and delve into the sensory stones. We come to understand the ideology of these factions because we experience their fundamentals for ourselves rather than having it explained to us through meager description. To prove this is not simply the famous rose-tinted glasses talking, there are actually exceptions. The Harmonium, a faction you may not even remember despite playing Torment, make up a rare example of Torment faltering, leaning on dry description to explain their place in sigil.

But mostly, Torment is more elegant than this. We know that Dak'kon doubts himself not because he tells us "Oh by the way, protagonist, I currently have a crisis of faith" but because we slowly come to that realization ourselves by talking to him and experiencing the increasing fragility with which he describes the teachings of Zerthimon, until he finally reveals to us that we have surpassed his own understanding.

Even Edér, who so frequently receives praise for being well-written in comparison to other companions in Pillars of Eternity, often downrights tells us about his core emotions outright, rather than just letting that show through his stories about his brother.

Hold up Dak'kon, I don't get it. Are you saying you have a crisis of faith? Why not just tell us "I have a crisis of faith," then?

Paint With All the Colors of the Ashtray

Pillars of Eternity also champions the new wave of RPG dialogue writing that uses desaturated, descriptive text in between a character's sentences to describe the scene, the mood or the appearance of the character. You know the kind:

"So-and-so", the massive man said with a stern countenance, his breath smelling like the crotch of a Glanfathan crone. "But also this-and-this", he added with a playful gleam in his eye, making you dread his erotic intentions.

Paradoxically, the fact that the developers have chosen to desaturate the colors of this descriptive text show that somewhere, deep down, they realise its extraneousness. As much as it must pain writers who had their initial inspiration and experience from the world of books, we are reading dialogue in a video game here, not a novel. What the characters say is meant to convey the emotion and poignancy of the scene. Simply describing facial expressions and emotional states is akin to a movie using voice-over to explain the innermost thoughts of its characters. Even when David Lynch does it, it rarely, if ever, works.

There is a place for this kind of stage-setting, but only if it used for a specific purpose - to characterize an important trait of a character or draw the player's attention to a specific circumstance. All too often, however, Pillars of Eternity and other, modern RPGs use the gimmick merely for fluff, filling the dialogue with a needless abundance of wordiness that players quickly learn to gloss over. In the end, the desaturation of the descriptive text becomes a convenient measure for players to quickly skip over reading it and, more often than not, nothing is lost as a result.

Planescape: Torment had a lot of descriptive text because everyone you met was a weird demon/angel hybrid with hollow space-eyes that held the cosmic horrors of the endless planes. It also did not color the text differently, because when it was used, it was just as important as the dialogue. Do I really need an essay to describe how a Dyrwoodan hobo chews his food before he spouts what might be a relevant line of dialogue?

One novel concession that does work in Pillars of Eternity, however, are the text adventures. Instead of overtaking the dialogue screen with superfluous text, these small, contextual puzzles constitute an entire mechanic of their own, allowing the developers to take your character through events that cannot be handled by the game's core engine. The text adventures allow you to rescue people from burning buildings, test your character's attributes and skills in innovative ways and close off or open up hidden paths through areas. A few seem unnecessary and have too few implications in the game or only exist to describe things you can plainly see from looking at an area, but many represent well-timed shifts in game pace. They slot naturally into the game and give Pillars of Eternity a tabletop feel that the Infinity Engine games rarely produce.

It is a mechanic so naturally fitted to roleplaying games that I would not mind if it became a staple in the genre, included in nearly every game.

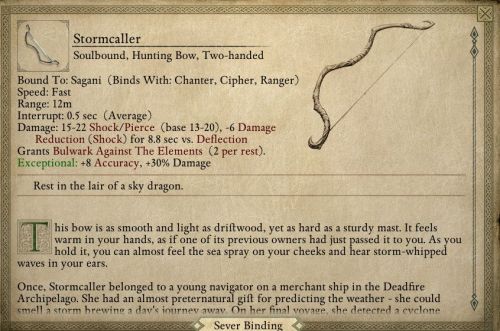

The White March expansion improved on the text adventures in most ways. Above, a text event with multiple skill checks, attribute checks, different results if you send in specific companions as well as more than a few success and fail states. Below, a text event that can grant you one of the special Soulbound weapons from the expansion - weapons with special upgrade requirements and related quests.

All in all, I have no wish to be too rough on the setting and style, here. Most of it is crafted so methodically and with such an eye for detail it sets itself squarely apart from much of the fantasy slog video games present us with. How many other fantasy roleplaying games manage to discuss so pertinent themes as colonization of wild habitats, structural determinism and the essence of governance without becoming preachy or pretentious?

The graphical representation of it all is also sublime, and everything from the gorgeous backdrops to the details in the dialogue box is beautifully painted.

It is simply that while Pillars of Eternity's setting has more serious aspirations than most RPGs, it fails to live up to them.

(For further reading on how many of Pillars' problems with over-exposition and infatuation with "deep lore" are genre-wide, I recommend RPG Codex user Darth Roxor's excellent editorial on the subject.)

All Is Not Well That Ends Well

Pillars of Eternity's story bases itself entirely on a twist-and-reveal gimmick. The twist in itself is executed fairly well, and the last one or two hours of the game, after entering Sun in Shadow, is where the story starts to take shape and become enjoyable. In that final part, the game provides both the player and the villain with much-needed motivation and contextualizes the setting in an interesting way.

Until that point, however, everything is nonsensical and veiled, to the point where you, as a player, lose interest.

One of the main causes is the complete lack of reason we are given to care about the main villain, Thaos. In fact, up until the very end, we literally know nothing about him. To compare him to the villains of Baldur's Gate, Thaos' ambition is initially clouded like Sarevok's, but as a character Sarevok is so simple and menacing, even a child can guess that his motives are cataclysmic. Baldur's Gate chose a simpler route than Pillars of Eternity and, as a result, does not have to dwell much on its antagonist. Irenicus is more complex than Sarevok and because of this, the game dedicates significantly more screen time to him. His story unfolds step by step, giving us clues to his exile, his lost love and his aspirations to godhood to keep us interested. The very starting area of Baldur's Gate II and the following cutscene is entirely devoted to setting up Irenicus' character because he is so important to the plot.

Thaos is not only even more complex, but also more than just the main villain. He is the central figure around which every single element of the main story - including you, the protagonist - revolves. Yet even the most minute details of his murky reasoning and hidden alliances are completely obfuscated until the very end of the game. In exchange for a good reason to track him down, the writers fall back on the player's impending, but vaguely defined, doom, which just about ranks number one as far as forced motivation goes.

As Thaos is at the core of everything the game is attempting to "be about", this essentially means that the entire story of the game takes place during its final hours. Until then, we are just chasing a ghost because of an undefined connection to an event we did not understand that had an effect on us that is never explained, though we are told we have to chase Thaos, lest we expire.

So how do you make a story spanning over 80 hours work when you cannot give any details whatsoever until the last hour? The writers of Pillars of Eternity clearly could not answer that question. They tried desperately, even throwing Thaos' old love interest at us who, unsurprisingly, has nothing to say about the man, because remember: due to the game's twist, we cannot learn anything of substance about him until the end.

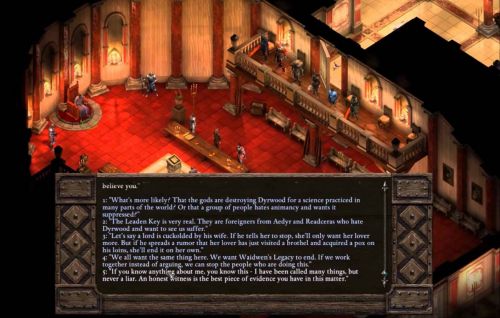

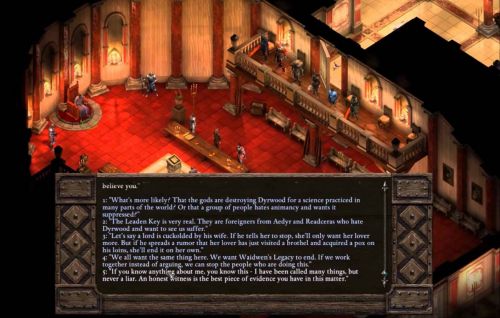

Pillars of Eternity is at its very weakest when it asks you to click through dialogue scenes of your character's past life as a member of Thaos' organization, The Leaden Key. Because the story must be devoid of actual meaning or detail to conceal the plot twist, these flashbacks are given to us using placeholder expressions like "The Inquisition" or "The Woman" - descriptors that describe nothing because we are not informed about their meaning until the end. The flashbacks exist to fool us into thinking the first 75 hours of the game has a main plot, when the reality is that most of it is told in the last five.

Where the main plot fails, however, Pillars of Eternity tells many smaller stories that work better. The childless Gilded Vale is a haunting place, expertly constructed and connected to every theme present in the rest of the game. Where the importance of souls seems overstated or under-explained in the game's main story, the Hollowborn are a brilliantly horrifying invention. Gilded Vale has been driven mad by the slow deterioration caused by the curse. Citizens react with mistrust, the artists have drawn a township and its surroundings in unrestrained decay, and the lord of the land has turned corrupt from personal grief and the burden of government. It is the story of King Théoden from Lord of the Rings, but instead of a literal Wormtongue whispering lies in his ear, it is circumstance that has driven Lord Raedric to madness and despair.

Everything from the way Raedric slumps in his chair to the lighting in the keep supports the themes at play in this story.

When Pillars of Eternity zooms out and attempts to juggle all of its themes in a large, overarching story, or when it tries to cram the detailed setting into characters spewing descriptive dialogue, it fails. But in a few places, when it zooms in, the obvious capabilities of Fenstermaker, Patel and Veras shine, as does Sawyer's interest in how mundane, historical troubles like childlessness can be given a creative fantasy spin and suddenly spark our imagination.

Would You Like Some Consequence With Your Choice

Gilded Vale also works as a vehicle for one of the main subplots: how the constant progress in the field of animancy is causing controversy through the Dyrwood. During your playthrough, many quests, faction interactions and companion banters point towards this Gordian knot of political strife: how will the administration of Defiance Bay handle the scientific developments in the field of soul manipulation?

Despite the writing's flaws, this plot is set up well enough and handled with a maturity that completely shames the majority of modern computer roleplaying games. Yet here, too, Pillars of Eternity undercuts its own designs. All threads in the animancy plot converge at a massive trial-like event, harking back to one of the most (cruel voices would say the only) lauded parts of Obisidian's earlier roleplaying effort, Neverwinter Nights 2. In Pillars, your character gets to be a deciding factor in how Defiance Bay – the capital of the game's region – reacts to the growing influence of animancy. As you argue your points, nobles, faction leaders and other characters present at the event comment on your progress and the way you have handled yourself during the game. Some use it to your advantage, highlighting certain actions you took as praiseworthy, while others condemn you for them. It is a majestic piece of reactivity that puts you on the edge of your seat as the game suddenly brings up choices you made on a whim and imbue them with new meaning. Will the citizens of Defiance Bay react favorably to animancy and view it as the key to ending the Hollowborn curse, or will they detest it for being its cause? In contrast to the player's status as 'THE WATCHER', which is entirely unearned by you as a player and forced on you by the writers, your role during the animancy hearings feels like the result of your own actions.

The main character gets a chance to argue her case based on past decisions at the final animancy hearings. Too bad none of it matters in the slightest.

And then, at the apex of the scene's tension, it all falls apart.

As Defiance Bay is about to make its choice, Thaos assumes control over an animancer present at the meeting and assassinates what is essentially the mayor of the city, causing everyone to side against animancy. The entirety of what you just witnessed – your every choice being weighed, you arguing your case, defending your past choices and listening to the NPCs commenting on them – is entirely nullified by the writing's heavy-handed intrusion.

Pillars of Eternity makes a big deal about giving you agency, and then explicitly annuls its own ambition because the main plots necessitates it.

Fortunately, Pillars of Eternity's reactivity is much more subtle and less defeated by its own plot in most other areas of the game. Once again, Raedric's Hold in Gilded Vale is a high point, with a staggering number of ways to reach the end of the quest, multiple solutions once you reach that end and a few long-term consequences, like the lord of the castle returning as a vampire. During my first playthrough, I completely missed an entire area of the castle with its own sub-quests as well several alternate ways to complete the main path.

Winter Came

Had I written this review before August 25, 2015, perhaps it would have ended here - with mixed feelings punctuated by the aforementioned metaphor of a finely cooked meal seasoned with toxic ash.

However, on this date, Pillars of Eternity changed from a promising, but unfulfilling, game, into a masterpiece.

'The White March', Pillars of Eternity's expansion, is a testimony to what iteration and continued passion for a project can do for quality. Its narrative removes the tiresome focus from the player's role as the writer-imparted chosen one, except when it uses that gimmick for the explicit purpose of clarifying details about the story and resolving the conundrums of its main plot step by step. The story is simpler this time, less ambitious and more connected to Pillars' roleplaying roots. In many ways, Stalwart and its surroundings take the lessons learned from Gilded Vale and blows them up to fit an entire expansion. We meet believable characters with clear motives here and more importantly: we keep pushing to reveal the secrets of the ominous Durgan's Battery, secrets that are exposed to us in satisfying bits, each bit both feeding us information and deepening the wider mystery. Rather than every step bringing us another nonsensical flashback, we instead meet characters with something on the line; people, monsters and artifacts that each give us a piece to the puzzle.

With regards to atmosphere and art, Sawyer uses The White March as an excuse to return to his dearly beloved Icewind Dale and borrows in no small part from places like Dorn's Deep. The White March takes what made those areas work and grounds them in a historicism that works much better this time, because this time, most of it is delivered as the incidental byproduct of what characters actually experience and not through tiresome exposition.

The areas of The White March and Durgan's Battery absolutely reach the same heights of quality that Icewind Dale climbed to some 15 years earlier.

Just when we think we have finally uncovered the riddles of the Dwarven bastion, the game throws an even greater enigma at us: the giant Eyeless, a seemingly cataclysmic force of invaders with unknown motives that are once again unveiled bit by bit (astute nerds will notice similarities between the Eyeless and the tytans of the 'Death Gate' cycle by Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman, names that should be familiar to any fan of cheesy fantasy pulp).

It is epic fantasy at its best, with twisted, divine logic affecting the lives of the common man. Even more gratifying is the high level area 'The Siege of Crägholdt.' This quest constitutes what is perhaps the most indulgent bit of nostalgic, old-school D&D module adventuring in any modern video game, complete with liches and cabals of mystical archmages that have invented and thus lended their names to many of the spells you sling during the rest of the game.

It is a shame that grognards are so disgusted with Pillars of Eternity. If they were not, they might play through Crägholdt on Path of the Damned difficulty and discover that the art of fun adventuring, epic wizardry and tough-as-nails dungeon delving is not lost as long as Josh Sawyer yet draws breath and someone is willing to pay him for churning out video games.

Pillars of Eternity with its expansion is also a massive game, filled with so much content that you could easily play four "games within the game": you could finish the game by completing nothing but the main quest, you could play the expansion, play the megadungeon of Od Nua or play the staggering number of side quests. All these chunks each amount to a full game in terms of content.

In some respects, this adds an outright insane amount of replayability and ensures the value to money ratio errs squarely on the side of value. On the other hand, some of the content is plain poorly designed, like the stronghold of Caed Nua which, in its end state, is a tacked on pseudo-system of the kind Josh Sawyer usually chastises when he talks system design (though the Bounty missions from the Warden's Lodge offers some of the most well-designed encounters in the game).

When Pillars was announced, I had doubts as to whether it would be able to deliver the same wealth of content as Shadows of Amn did before it. As I reached Twin Elms on my first playthrough, I was already glutted with gameplay, and another city the size of Baldur's Gate seemed excessive. With The White March on top, Pillars is easily one of the most content-rich RPGs ever made, and it is not advisable to consume all of its content in one playthrough.

Winter Wonderland

While the story is an improvement in its restrained simplicity, booting up The White March on patch 3.0 after playing Pillars in its original state is like playing a different game altogether. Iteration is often neglected and rushed in an industry where gamers demand to play even before games are released and publishers push for short deadlines. Even so, Josh Sawyer and his team managed to not only iterate on the systems and gameplay of Pillars of Eternity – they went at the task of updating the game with an almost autistic fervor. News of the latest patch surfaced this month.

In terms of gameplay, the constant updates, tuning and tweaking have paid dividends.

In a display of intellectual honesty that few designers can boast of, Josh Sawyer recognized his mistake and reintroduced counters as a larger part of the gameplay to incentivize tactics-switching. Obsidian's team refined the character system and made many talents more build-defining, while simultaneously diversifying abilities and nerfing strategies that were too efficient. The White March also features encounters that feel like Obsidian had a whole team of people who did nothing but plan out, test and re-test battles, filling areas with monsters placed in innovative and annoying combinations – especially on Path of the Damned difficulty – to encourage even further planning on the part of the player. Spamming the same abilities fight after fight is no longer an option, not only due to enemy resistances, but because of the placement, attack type and abilities of your opponents. Even a few, basic trash fights in difficult areas such as Longwatch Falls demand diverse tactics.

A slide from a talk by Josh Sawyer at the Game Designer's Convention, GDC. Note the acknowledgment of needing hard counters.

Speaking of Path of the Damned, this difficulty mode finally got its chance to shine with the AI updates and varying monster defenses. What is a push-over trash fight with a few fighter-likeSahuagin Lagufaeth on easy can become an all-out brawl with specialized casters, pesky, fast-attacking ranged units and a front of fighters that are hard to pass with your melee characters and which, if you do, will often switch priorities and attempt to finish your backline before you finish theirs.

Combat on the latest patch can still be trivialized by abuse – as is the case with every other RPG – but never has it been more difficult, and never have the challenges felt more diverse. Pillars of Eternity is a slower, more unwieldly version of RTwP combat than its Infinity Engine predecessors, and it lacks the epic mage battles of Baldur's Gate II. With the latest updates, the game makes up for these knocks with some of the best encounter design in RPG history, a finely tuned character system and a 'hardest' difficulty level that feels so different to play, it might as well be a different game altogether.

There are dragon fights that feature attacks patterns so diverse you will struggle between learning them and focusing on your own actions during combat. There are avalanches of dwarven tank fighters that whittle down your party's health and ability uses. You will face high level kobold (sorry, 'Xaurip') ambushes that engage you on three levels of the same area while you struggle to control the important enemies. One encounter features a massive, 20+ enemy skirmish with human mercenaries being mind-controlled by the Mind Flayer-like Vithracks. This encounter in particular will test your crowd-control capabilities and understanding of the Engangement system as enemy berserkers launch into the air and drop on your casters. It will also test your ability to focus on the correct enemies, which, by the way, may not be what they seem at first. Groups of ghosts will strain your reliance on your characters' abilities complementing each other as they take turns being paralyzed and thus taken out of the combat equation. Monks will play racket ball with your guys, spreading them over the entirety of the battlefield while you struggle to rally your troops and push back the onslaught. Impressively coded mages will sling a multitude of spells that change dynamically depending on your own combat actions and, if you are good enough, you will face off against two dragons AND an archmage (I had to give up on that one and solve it through dialogue – making it the only fight in Pillars I have not beat).

Fighting the archmage Concelhaut takes you back to your earliest, tabletop adventuring years, when your group would embrace the GM's Elminster or Mordenkainen cameos with glee. It's a cheap thrill, sure, but it's also part of what makes Dungeons & Dragons adventures fun.

The strength of these encounters is thanks in no small part to a continually updated AI. At launch, enemies in Pillars of Eternity would beeline towards the first character that provoked them into action, using repetitive attack patterns and a small array of skills while you wailed on them with whatever rote strategy first worked for you. Multiple patches corrected enemy behaviour, added abilities and defenses to boring enemies and padded out encounter diversity. Here, too, the obvious Sword Coast Stratagems-inspiration becomes apparant, as difficulty in White March arises from clever enemy targeting and ability selection just as much as from raw power.

In this sprawl of diversity and unique encounters, the hardest encounter that I did beat was a company of fanatic Magran-worshippers – mechanically, the encounter features some very nasty area of effect-spam by priests hidden behind self-buffing druids and a couple of tanks.

On top of the painstakingly detailed encounters, Pillars' character system has been expanded and diversified and the amount of possible builds and party compositions is staggering. Talents will greatly alter your character, and depending on what you pick, the same class can be a staunch supporter, an AoE-based damage dealer or a Zone-of-Control extending tank. Currently, the best melee build might actually be a self-buffing Wizard that functions much like the Fighter/Mages or yore, achieving momentary power surges through spellcasting. Discovering all these options, testing them out and finding that clever combinations will actually work is immensely satisfying. Even a few races can shape your entire build path; building a moonlike Paladin and specializing in the racial ability can make her an incredibly efficient healer.

My next playthrough will feature four paladins as the party's backbone, and while they will all pick up the same low-radius AoE damage abilities in the late game in an attempt to stack them on top of each other, their initial, different talents and combat styles will make them feel like four distinct characters. This is in no small part due to another sound success of Pillars of Eternity, making each weapon type and gear setup feel distinctive. In the original game, these differences were masked by poor design choices - mainly that rote strategies could defeat every encounter. In The White March, however, the differences between the weapon types shine.

If you are not paying attention, chances are as well that you will find some encounters oddly easy and some nearly impossible if you rely too much on the same strategies or are unwilling to have different weapon setups. The trick is that resistances, defenses and the armor type of your opponents have a huge impact on the number-crunching in the background, and switching attack types can be as important as changing the overall battle plan.

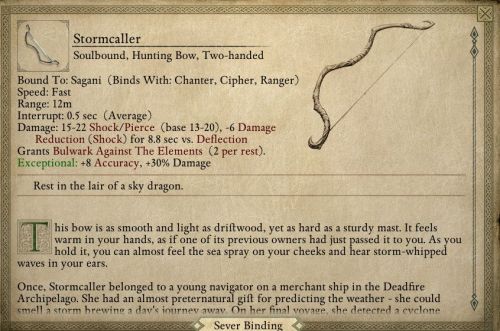

Besides killing creatures to unlock their abilities, Soulbound weapons feature requirements as diverse as meeting certain combat states (dominate multiple creatures or be revived during combat) or even have you go on pilgrimages to places in the game world only hinted at through a riddle in the item's description. Possibly the coolest version of artifacts in any computer RPG.

Itemization is another area of the game that has moved from simple sufficiency to elegant beauty. The amount of variety on display both in terms of basic gear types but also in unique equipment and item abilities has not been rivaled since Shadows of Amn. Everything from basic abilities like giving your characters another chance when they are reduced to 0 hit points to granting unique spells that can only be cast through that specific item to granting conditional immunities or buffing your character while prone. Choosing between these items is rarely a simple problem of just picking the one with the highest stats, but rather demands you factor in which enemies you are fighting, what your character build is and how your gear can become an extension of your character's abilities. Agonizing over which of all these items you are actually going to equip nevermind on which character is pure, clean RPG fun, and once you have played through the game once or twice, you will definitely have found items which inspire you to craft entire characters around them. To add to this diversity, new and very rare crafting ingredients dropped by bosses or given as quest rewards allow you to add unique enchantments on top of your favourite items.

It bears repeating that with patch 3.0 and The White March, combat and character customization in Pillars of Eternity has been iterated from a great idea with mediocre execution to something resembling flawless implementation. Excepting further games in the series, it is undoubtedly the closest you will ever come to playing Baldur's Gate II with the full Sword Coast Stratagems package – and, in many ways, it is superior. Some will find the sluggish control less appealing – it is for me – but there is no denying that the strategic variety is greater in all encounters save the most well-designed mage- and boss-battles in the Infinity Engine games. That The White March also features the most indulgent trip down D&D memory lane you are likely to play on a computer in a long time in the form of dungeon delving, lich battling and loot hunting makes the experience all the sweeter.

The lesson is that iteration is as important as having a good idea to begin with. In this regard, The White March mirrors the extensive patching and modding cycle of Baldur's Gate. Today, no die hard fan would play the Infinity Engine games without Sword Coast Stratagems, which represents one of the most detailed, iterative processes in RPG history.

Likewise, Pillars of Eternity without the latest patch, The White March and Path of the Damned difficulty is a shadow of itself, unworthy of your attention. But the full game, polished and perfected as it is, is simply a joy to play - glorious in all its complexity, sprawling wealth of content and diverse challenges. The final product after two years of patching bodes well for Pillars of Eternity II: Deadfire, should the lessons be carried over. In terms of gameplay, Baldur's Gate II was a clear improvement on the original and if the same is the case with the sequal to Obsidian's first, Kickstarted game, some of the IE games might finally be knocked off their perch as my favourite games.

Conclusion

It is a harsh companion, nostalgia. It deceives you into thinking the magic of childhood remains magical and sours what should be enjoyment of modern marvels. So many Kickstarted games have fallen prey to its lies, implementing stock ideas that were already outdated at the time in misunderstood attempts to stay true to the source material. Other games from the industry at large have claimed to be "spiritual successors" to beloved games of yore, only to shed themselves of what made the original special in panicked attempts to appeal to modern audiences.

Pillars of Eternity: The White March is a rare phenomenon because it sorts through the past with clarity of vision, doing away with quaint mechanics and obsolete system design while holding onto what always worked, what was never broken to begin with.

The core game fumbled somewhat, trying to juggle the ambitions of tomorrow and yesterday and thus delivering a mediocre compromise. The writing of the main game cannot be saved, yet still shines bright in this nook and that cranny. What was added after release went back to the basics, removed the burdensome focus on the player character and focused on just delivering a damned good story. The gameplay has been iterated to perfection with the patience of tenacious custodians in the form of game designers and playtesters.

The game in its current state is, above all, mechanically elegant. Where nearly all other Kickstarted games were mismanaged, promised too much and delivered too little, Pillars of Eternity: The White March was gifted with the oversight of a restrained and professional project lead, a devoted team and an almost conscientious pledge to deliver on nearly all of its promises.

Actually playing Pillars of Eternity: The White March reminds me why I still own a PC. Nothing less.

A retrospective on the Infinity Engine games and Pillars of Eternity

It is a cruel friend, nostalgia. It initially aided me as I outgrew my childhood, letting me hold on to at least some of the love I once had for this cartoon or that toy.

Then, as critical awareness evolved with age, the same nostalgia that once tinted my proverbial glasses with a rose hue reminded me that all I had left for many of the things I used to love was exactly that: nostalgic reverence. There was no legitimate reason to enjoy so much of what I once cherished.

This is especially pronounced when it comes to video games. Nostalgia was the last remaining barrier between cynical rejection and adoration for several games that I used to like. Neverwinter Nights, for example, plays poorly and the story is a cavalcade of the worst fantasy clichés, yet it takes itself seriously. I also recently replayed the original Knights of the Old Republic, which was a thoroughly disappointing experience. The gameplay is an awkward abomination of over-the-shoulder shooting and tactical RPG. The writing is so childishly blunt it has Sith characters laughing maniacally with voice acting borrowed straight from saturday morning cartoons as they commit everything from schoolboy pranks to vile acts of torture.

Other games that still hold up as a whole show cracks where none were visible before. The combat of the Might & Magic series has very little interesting going on and rarely takes advantage of the game's luxurious spell selection. Westwood's 'Lands of Lore' is pretty, but otherwise the game pales when compared to other, better games in its genre. One such better game is Wizardry 8, but excepting the most fanatic fans, anyone who has played it will admit that this old-school titan has an excessive amount of fights that take needlessly long to complete, making an otherwise excellent game a veritable slog even as early as the midgame.

Though it amounts to heresy around these parts, even mighty Fallout has blemishes: simplistic combat and a shallow, unbalanced character system being the worst.

The part of adulthood that is harshest towards enjoyment of video games is developing the curiosity to sample some actual great literature and watch a few of the choicest films. Exposure to actual quality might bring you to the realization that the games industry is stuck in a juvenile rut, and has been since the inception of the medium. These days, I find that nearly no piece of entertainment that I used to enjoy as a kid can withstand the full thrust of adult cynicism.

Except, perhaps, the Infinity Engine games.

That Bridge Crossing From Tomorrow to Yesterday

They are not perfect games - far from it - and I cannot deny a personal bias here, in that so many of the games' fundamentals appeal to my tastes specifically. Excepting Planescape: Torment, none of them certainly constitute art in any sense of the word. But perhaps their innocent ambition to combine damned good gameplay with narratives that have little ambition besides facilitating frolicking adventures is precisely why they still hold up.

The first Baldur's Gate, for instance, takes you on what might be the closest video games have ever gotten to recreating the immaculate excitement of the earliest D&D adventure modules. All that is absent is starting the party at an inn. That part is delayed until an hour into the game, where you pick up Khalid and Jaheira, whose story around a table filled with character sheets, dice and empty coke cans would most certainly begin with the words "you're sitting in an inn. Gorion's ward enters."

In the same vein, Icewind Dale is a magnificent tour of the combat-heavy, almost wargame-like dungeon crawls of the eighties, seasoned with the long-forgotten craft of actual, evocative fantasy art and locales. People past the emotional age of 14 who look at Icewind Dale's artwork will feel a natural inclination to weep at how modern works of fantasy choose to depict their worlds.

If these images do not ignite your imagination, perhaps you also think the prequels had better lightsaber duels?

Bringing up the rear, Planescape: Torment has by far the weakest gameplay but the strongest story and one I was surprised to find, when I replayed it last year, holds up to the scrutiny of a critical adult, now well-versed in media that aspire to more than entertainment. Torment explores its themes proficiently, the story is constantly surprising and there is actual depth there: motifs integral to humanity that are worth discussing. Most of all though, it is wonderful; with some new marvel or impossible phenomena awaiting you on every area load.

The sequel to Baldur's Gate, 'Shadows of Amn', does what any great sequel to a good game should: damned near carbon copies the entirety of what works including graphics and audio resources, ramps up the stakes in the story, refines the writing and expands on the systems and gameplay already in place. It also starts to show the path that will ultimately doom BioWare's brand of RPGs, with a few of the companions acting like annoying and whiny teenagers in the middle of a world-shaking conflict. Mostly though, the experience holds up. Overall, the writing certainly matured from the almost non-writing of the original Baldur's Gate's side quests (siding with the druids on the grounds of aloe vera balm, anyone?). Irenicus is a strong villain, voiced by an even stronger actor in what is arguably the best performance of his career.

In all but Torment's case, the IE games' conceit of coupling modern RTS-like gameplay with the tactical, squad-based combat of traditional D&D succeeds completely, despite the concept being so at odds with itself. The games give you the frantic thrills of StarCraft's rushed micromanagement with greater input required per unit and the tactical control of a pause-button.

What might be the most direct predecessor to the Infinity Engine games bears mention here: without the unique ingenuity of 1992's 'Darklands', had Baldur's Gate's gameplay ever assumed the form it did? Maybe – but surely someone, somewhere at Black Isle or BioWare must have fired up Microprose's historical RPG and thought, "hey, this is pretty cool".

This style of gameplay, dubbed 'RTwP' (Real Time with Pause), was BioWare's attempt to bridge the tactical construct of yesterday's dungeon crawls with the, at the time, insanely popular top-down strategy gameplay of tomorrow, StarCraft having just been released. The mutated compromise they developed as a result is often criticized, but not for entirely respectful reasons. Most criticism boils down to the fact that there is little overlap between the people who enjoy the fast-paced, action-per-minute-driven battles of an RTS and the people who enjoy pondering endlessly over decisions in a turn-based game. For those strange creatures who do appreciate the mix, the Infinity Engine set the standards for everything that would follow. Add in some modern coding with modder DavidW's "Sword Coast Stratagems", which balances a few systems and makes the AI surprisingly sophisticated for an engine released in 2000, and the result is a combat experience iterated upon to near perfection, perhaps more so than any other game in computer RPG history.

What will probably be your first dragon fight in Shadows of Amn awaits you at the end of a major side quest with its own a score of subquests and a lengthy dungeon crawl.

Somehow, even the terribly outdated character system – "Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, 2nd edition" – with its poor balance and horrid lack of character customization options, has been gracefully woven into these games. The designers correctly chose to focus their efforts on AD&D's spell system, which might be the one part of the game worth preserving. Much of the actual enjoyment of an IE-game is pausing to set up a particularly devastating spell, then unpausing and controlling the positioning of your characters, adapting to the new state of the battlefield.

Systems & Sorcery

The character system is worth dwelling on as we start to delve into the IE games' spiritual descendant, Pillars of Eternity. (And no, we are not counting Dragon Age here, because despite an honest attempt from the first game, Dragon Age 2 and 3 made it quite clear that BioWare had no actual ambition of refining the formula, but rather meant to capitalize on nostalgia for the IE games).

Pillars of Eternity is nothing if not the story of how to rethink an iconic character system. In so many facets of its development, Pillars stays true to the IE formula: the combat controls are so similar only hardcore fans who have played the IE games multiple times can tell the difference. Graphically, the game interposes avatar sprites of characters on gorgeous 2D images. You have six party members who bark at each other and at you, and you have a completely open world map with smaller "point of interest" locations to visit, sometimes gated by story progression. Exploration is handled by "painting" a black background consisting of fog of war with your characters' line of sight as you move through the area. When you click on an non-party character, it brings up a dialogue screen with multiple, fully written-out lines of responses for you to choose between.

The character system on the other hand has undergone an overhaul so massive that any resemblance to the original remains almost symbolic. Yes, both systems are class-based, yes both systems have you level-up to gain new abilities and yes, there is even a remnant of the "Vancian" spell system in there, since spells are limited to daily castings – though even here, the system lacks the trademark D&D spell memorization.

To understand how and why Pillars of Eternity takes such an extensive departure from the genre's D&D origins, we must take a moment to discuss the character system of the IE games, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, 2nd edition, in more detail.

It is impossible to make a concise statement on the vision behind Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, because their simply was none. In the rulebook's foreword, creator Gary Gygax speaks of a creating a consistent framework for games, of adding uniformity to campaigns and of shedding the arbitrary distinctions so often present in rules systems at the time. He even speaks of the need for BALANCE™, which is ironic since it has made the Lead Designer of Pillars of Eternity, Josh Sawyer, so reviled by the same grognards who revere Gygax and who claim system design was perfected with AD&D.

Yet in the substance, Gygax' intro reads like a politician's glorious statement of intent before he inevitably breaks every campaign promise.

To start with, AD&D's biggest sin is that it is arbitrary in the most literal sense of the word: "based on random choice or personal whim, rather than any reason or system." The irony that Gygax himself mentions arbitrariness as a hazard to avoid in system design is completely baffling considering the fact that arbitrariness might well be considered the defining trait of AD&D.

Why do all attributes go from 3 to 25 specifically? Why does Strength have a special 01-100 sub-attribute only if you are a specific class and only if you have a score of exactly 18? What is the reasoning behind the reversal of the to-hit roll, asking you to go backwards on the number line instead of forward? Why do Clerics only have access to seven spell levels while Wizards have access to nine? Why do you roll for hit points until level 10 at which point you gain minor, static increases? Why does a Ranger need 150,000 experience points to progress from level 8 to 9, while a Wizard needs 45,000? Why must an Illusionist have a minimum Dexterity of 16? Why do Clerics gain bonus spells for high Wisdom, while a Wizard gains no similar bonus for high Intelligence? Why is it easier to save against the same spell cast from a rod or wand rather than if a mage cast it? Why is the difficulty of resisting a spell based solely on the target's level and not on the caster's? Why are certain combinations of multi-classing restricted from certain races? Why does dual-classing work on an entirely separate system, and how do you forget everything you learned about shooting a bow and arrow because you decide after 10 years of rangering to pick up clericing? Why is there a specific attribute for "bending bars" and why is it handled by a percentile roll when "Open Doors" is not? Why do thieving-abilities work on a completely different, percentile-based system compared to other skills and class features?

Why, why, why, why, why?

"No no, I assure you, everything in this table was implemented with the utmost care to abstract reality and make for good gameplay." Riiiiiight.

The answer to all of these questions – the answer to almost any question regarding the system design of AD&D – is: "because the designer felt that is how it should be."

Or in more modern terms: for shits and giggles.

In addition, AD&D is actually a fairly simplistic system despite the "advanced" moniker. Most level-ups will result in a hit-point gain, perhaps a THAC0 increase (or decrease, depending on how you want to look at it) and little else, unless of course you happen to be casting spells, in which case you might be granted a couple of spell slots. How many times do you level up in the IE games, only to simply click "OK" and move on? Paradoxically, AD&D at once embodies this superficial simplicity yet is designed to be more convoluted than is actually necessary for the thin substance it represents.

I really only included this picture to hammer home the point that modern fantasy art ain't got shit on the 80's and 90's.

Most of the very best tactical cRPGs of the past are great despite the shackles of AD&D, not because of them. Of the AD&D games, the one praised the most for its character system is Wizardry 8, which offers a staggering range of classes, races and customization options, all of which are viable in the game. Yet this praise is also damning to AD&D, because Wizardry 8's system is so heavily modified you can barely recognize Dungeons & Dragons beneath it all.

Gary Gygax is worthy of respect for putting more narrative, context and adventure into what was once merely wargames. If not for him, we would have never experienced the wonder of roleplaying games backed by interesting and unique gameplay systems. The fact is, though, that AD&D is massively inferior to nearly every rules system that has followed it.

Which brings us to Pillars of Eternity.

This Ain't Tabletop No More

It was no surprise when Lead Designer Josh Sawyer admitted that lack of licensing was not the only reason that Pillars of Eternity would free itself from the chains of D&D. After all, the most fine-tuned version of D&D, the 3rd edition update 'Pathfinder', is based on an open license and completely free to use.

Rather, Sawyer's personal distaste of the system played a significant role.

The switch from D&D is the single-most impacting change that Pillars of Eternity makes to Ye Olde Infinity Engine, and as the original Kickstarter rolled out, it was an oft-cited reason to be skeptical of the game. I was among the skeptics since for all my dislike of AD&D I love the version of Dungeons & Dragons that followed it. This system, called "3.5" for short, is, despite its non-existing game balance, an incredibly fun sandbox in which to customize RPG characters and toy around with different builds. If you crave balance to the degree that Josh Sawyer does, D&D 3.5 and Pathfinder are kryptonite, but if you love having an infinite array of character customization options at your disposal, they just about represent the pinnacle of RPG design.

Josh Sawyer wanted something else. He wanted to finally bring RPGs fully into the digital realm. He insisted that tabletop and computer RPGs were so different that rules systems needed to be designed with the specific medium in mind. And he wanted what has made him infamous amongst the basement-dwelling, character sheet-loving "grognards" of the tabletop world: game balance.

Knowing that Sawyer was going to design a new system from the ground up was my main concern about Pillars. The open license version of D&D 3.5, available free for everyone to use, could have saved Obsidian and Sawyer a vast amount of effort. As Sawyer began posting development logs however, it became clear that he had a strong vision for RPG system design, and curiosity quickly substituted skepticism.

Clearly a man who understood the Infinity Engine, had extensive tabletop experience and a precise idea of how to evolve RPG design. The terrible dad jokes came with the territory.

Would Sawyer deliver a game with the core of the IE games intact but with their sole, lackluster component fixed?

In that case, count me in.

Le Petit Éternité

When I first finished Pillars of Eternity, it was with an odd sensation of disappointed near-fulfillment. Like I just eaten a fine meal seasoned with ash. Everything from the gameplay to the story showed infinite promise, but nothing quite delivered on the theoretical potential.

Very early in the development process, Lead Designer Josh Sawyer vocalized his dislike of total fail states in system design. Central to this dislike was a distaste for 'hard counters', like a fire elemental being completely immune to fire damage. For this reason, Sawyer also initially designed Pillars of Eternity's system with no misses, substituting them with "grazes" that dealt less damage. He also based his armor-system on gradual damage reduction rather than outright evasion. Furthermore, Sawyer announced his goal was to make every skill, talent and attribute of his system useful. Not necessarily equally good – but the intention was to make sure that there were no "traps" – abilities which were downright awful.

In theory, I lauded these goals, which were predictably criticized by grognards everywhere for being implicitly poor design. The grognardian criticism was based on the idea that there must be bad abilities and pitfalls in order for players to feel rewarded for building a good character. I certainly do not mind systems that do this – I am an avid Pathfinder player in my spare time, after all – but I also fail to see why it should be a general rule. With Pillars of Eternity, Sawyer was attempting to give the player a framework of classes and abilities that they could toy around with to their heart's content, safe in the knowledge that all combinations of assets in the system would at least provide some measure of functionality.