RPG Codex Review: Tale of Wuxia

RPG Codex Review: Tale of Wuxia

Codex Review - posted by Infinitron on Fri 25 October 2019, 20:11:11

Tags: Heluo Studio; Tale of Wuxia[Review by Darth Roxor]

Ancient Chinese secret

Hey. Let me ask you something. Did you ever feel like your favourite RPGs suffered from a critical lack of explosive flying roundhouse kicks? Were you ever of the impression that you really missed having a calligraphy skill? And wouldn’t you agree that a zither would make for an excellent weapon?

If you answered “yes” to any of these questions, odds are you might need more wuxia in your life. It is also very likely that you haven’t heard of the one game that can satisfy all your crazy Chinese kung fu cravings. That game is called Tale of Wuxia.

It was released in 2016 by Heluo Studio from China, which is how you know that it’s the real deal and not some cheap gweilo knockoff. Though actually it’s a remake of the studio’s earlier game from 2001, known as “Legend of Wulin Heroes” (it was never released outside China, I believe), which was a tactical RPG/princess maker based on wuxia novels by the writer Jin Yong.

You’ve probably never heard of any of the names and titles mentioned in this introduction. I know I hadn’t before trying this game. Not to mention it took me years before I did give it a spin. And the only thing I can say is that I regret it took me so long to do it.

So you want to be a xia

Tale of Wuxia’s main tagline is that it “has been dedicated to providing gameplayers with a player-defined platform, where they can customize their own Wuxia” (“Wuxia” is Chinese for “martial hero”), so as you may imagine, character building is an important part of this game.

And what a platform for character building it is! When you look at the system at first, you might get suspicious, because it has all the elements that don’t work in most other games, and which lend themselves to a great many trap builds. I’m talking of course about the multitude of statistics (there are around 40 things to raise), and the fact that seemingly useless things (“tea-making”, “calligraphy”) are coupled with what looks like obviously superior options (combat stats). In another game, you’d identify the dump stats, pump your sword skill to maximum and set sail to victory.

This is not at all the case in Tale of Wuxia. Here, all the statistics, from floriculture to martial arts, are useful to some degree, for a number of reasons. For starters, most combat styles in the game scale off two abilities – a primary combat skill and a secondary skill. For example, there’s a Taoist sword-fighting style, whose effectiveness is influenced by your skill in calligraphy. Similarly, a throwing weapon style will need high chess-playing. A zither (yes, the musical instrument) fighting style requires a high score in music. So on and so forth.

Also, a word on how the styles actually work. Apart from being influenced by a primary weapon skill and a secondary support skill, they usually give you a set of three unique moves in combat, though the most basic ones may be limited to two moves. All the moves require energy (mana, more or less) to perform, while the higher-tier abilities are only unlocked when you reach enough proficiency in a given style, and they also go on cooldown when used. Switching between styles in combat is possible, but it puts all the better abilities on cooldown, so effective switching requires a modicum of planning to pull off. The move sets are all clearly focused on a specific purpose, and the abilities often work best in combos. To follow the example of the Taoist sword style – the first, basic attack gives you a mana shield, the second move buffs you with vampirism (leeching both health and energy from damaged enemies), and the third is an area-wide slash that ignores armour. Proper combination of the three can leave you almost unkillable.

The versatility and flexibility when it comes to the combinations of skills and fighting styles gives tremendous freedom and breadth to the character system. The ways of building your wuxia are numerous, and you might switch between different styles many times throughout the course of the game – whether it’s because a new one you’ve just unlocked is more powerful than what you had before, or because you got bored of the old one and want to try something different.

Furthermore, raising various skills to high levels often gives you various long-term boons. These might be unlockable choices in adventures, skill check opportunities, or entirely unique events that are triggered only at certain skill thresholds.

There’s also a nice synergy between the above aspects, as the events you unlock often serve to let you gain new combat styles, which might not even be related to the skill that triggered a given adventure. Of course, these events will also net you experience, new acquaintances, items and the like.

Another element that ties all these parts together are the “internal arts”. These are basically passive abilities that boost your character’s performance, and their functionalities vary wildly. Some simply give stat bonuses (some of which keep rising the longer combat goes on), but others are more involved, and may give you a poisoning aura, let you move freely through enemy zones of control, periodically remove debuffs, etc.

Obviously the final piece of the puzzle that makes the system whole is equipment. You don’t get to play dress-up too much in Tale of Wuxia, as you can only have three items equipped at a time (a weapon, an armour, an accessory), but the bonuses they provide are still significant. Apart from the obvious features like boosting your attack and defence, your gear will also grant you additional abilities, which are not unlike the internal styles.

When you combine all these parts – stats, combat styles, internal arts and equipment – you can get so many, so different character builds and playstyles, it’s honestly almost overwhelming. You can mould your character into an unbreakable, ever-regenerating bulldozer, an artful dodger, a toxic avenger, a mass-slicer and dicer, Cacofonix, a ranged pinner and kiter, an immortal swordsman, a fan-slapping paralyser… and more. Or combinations thereof. It’s completely crazy, and it’s unlike anything I’ve seen in an RPG.

It is without doubt one of the best character systems I’ve ever had the pleasure to witness, if not the best. All the elements are in perfect synergy. There are no dump stats. The number of possible character builds is impossible to give, and getting them running is extremely satisfying. And most importantly, all the aspects come to a very elegant meeting in combat, which is the real meat and focus of the game, while also remaining relevant outside of it. I don’t know how much time and planning it must have taken the developers to establish this monster of a system, but I can give them the greatest praise for pulling it off.

With all that said, you might still be wondering how the character building process actually works in practice. This is also fairly interesting. As you start the game, your stats are all randomly rolled, and you have no influence whatsoever on this, apart from rerolling everything from scratch. The character generator also assigns three random traits to your character, which define your personality or attitude towards others – you might be chivalrous, which gives additional damage based on your “morality” stat, or smart, which makes you focus better on complex tasks, or nimble, which ups your dodge rating, and so on.

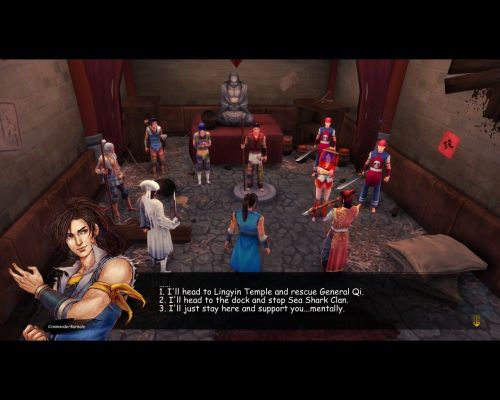

After that, the vast majority of your stat gains will be achieved through an “education” interface that is similar to all assorted princess maker games. It’s basically a choose-your-own-adventure layer that lets you train, stroll around in search of trouble, craft items and meet other people. This might sound simple and unexciting, but suffice to say – character building builds character.

That is because you have to balance a ton of things during the education mode. Obviously there’s training, which raises your very important stats. But that won’t let you unlock most of the good stuff that is “hidden” in the various events that you come across while strolling. However, skipping training like that will anger your master, which means you’ll have to do chores around the martial arts school every now and again to gain his affection back. It’s also important to keep high relations with most of the other characters you meet, especially your fellow disciples, since this can have huge consequences on how events, primary and secondary, may progress. Then there’s your character’s mood, which drops or improves depending on what tasks he finds boring, and which influences your experience gain. And finally, all these activities take stamina to perform, and your stamina pool for every “time period” during education is severely limited.

Obviously, during education you won’t be going only through CYOAs, as the phase is generously interspersed with various combat encounters or long excursions into cities. The most important aspect of these, apart from breaking any monotony that might arise from pressing the “train toughness” button too many times, is that these encounters let you put your character to the test, and give you great feedback on what you’re doing right or wrong. The game might be brutal if you build your character badly, but it gives you ample time and opportunity to identify your mistakes and correct them as necessary. Which is also very welcome, because for a longer while the complexity of the character system can simply leave you overwhelmed and confused. So every time you get stomped, it gives you another occasion for drawing conclusions.

Tale of Whoopass

With all this character building done, it’s time to discuss how the other major part of the game works. The part where you perform blazing somersaults to knock out evil henchmen and other ne’er-do-wells.

The combat engine in Tale of Wuxia is pretty standard when you look at the big picture. It’s turn-based, there’s a hex-grid, a bunch of combatants, each of them is limited to one move and one action per turn, etc. Every character has a pool of health (which can range from 1000 to 25000, so we’re talking big numbers), and depleting it means getting knocked out of the fight. They also have energy (“mana/stamina”, as mentioned before), which is required to take any action in combat, and whose management can be fairly important for low-cooldown/high-energy cost movesets, because if it goes down too much, you won’t be able to act at all. And of course there’s movement, which determines how many hexes you can cross a turn (it ranges from 1 to 5).

Characters have a number of secondary stats as well, which are no less important to how combat flows. Evasion lets you dodge attacks, counter lets you respond to attacks with free ones of your own, critical rate is obvious and so is accuracy. You also have percentage reductions to the opponent’s critical and counter rates, as well as a general defence stat for a flat damage reduction.

Overall, the system may look generic, but it serves as a solid foundation for interplay between special abilities, enemy composition, tactical opportunities and prayers to the gods of dice. And Tale of Wuxia makes use of this in very good, sometimes even spectacular, ways.

The true core of this game’s combat is putting your character build into practice and watching how ridiculously strong of a combo you’ve managed to devise. The dozens of special abilities available to you through internal arts and fighting styles make for a very exciting brew, particularly when you combine them with min-maxed ability scores that further serve to define your combat performance. Going for a poison-focused build lets you simply stand around and watch everyone get sapped of health and energy alike until they drop down and die. Pumping counter and combining it with an appropriate style will let you counterattack almost every time, while simultaneously accumulating critical chance. Pumping dodge may be risky, but it can also result in effective invulnerability.

However, all these combinations, and then some, are also available to your enemies, and you may find one day that your immovable object meets an unstoppable force. If you stumble upon enemies who more or less hard counter you, or are able to disable one of the key components of your build, it’s time to start improvising. Fortunately, given how you’ll usually develop your character along multiple branches, if you think hard enough, you may still find an ace up your sleeve that might just carry you through whatever hard fight that’s giving you trouble, even if it’s not as strong on paper as your “default” style.

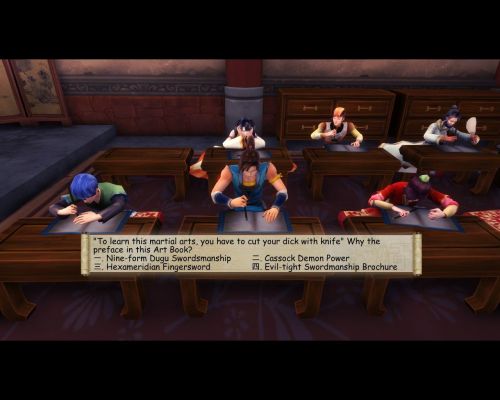

But there is one big issue about all these abilities, mechanics and sub-mechanics. Namely that some of them are very obscure and can be figured out largely by accident, some don’t match when it comes to their descriptions and actual effects, and some others still have names so very vague or uninformative, you’ll never guess what they do before trying them out (e.g. would you ever consider that “Teleportation Walk” is a buff that reflects incoming damage back at enemies?), especially since the game is pretty bad when it comes to documentation. There is no manual, the pop-up tooltips aren’t always very helpful, and the general state of English can be pretty damn broken, but more on this later. So in other words, be prepared to experiment a lot. Or find a guide on the Internet that has all the abilities and effects listed, if only for quick reference.

Nevertheless, to come back to the previous point, hard fights in this game are really plentiful. The best part perhaps is that Tale of Wuxia keeps ramping up the difficulty all the time, sometimes even to ridiculous degrees, just to keep you on your toes and remind you that there are always bigger fish out there. I would say there are a few “chokepoints” here, whose sole purpose is to encourage you to keep practising and making your character stronger. Each time during my playthrough when I thought I had achieved “god status”, and could not possibly imagine having trouble in a fight ever again, Tale of Wuxia then decided to show me how terribly wrong I was. And perhaps the best thing about this approach is that the vast majority of lost fights don’t lead to game over. You’ll still typically miss out on a lot of rewards and such, but apart from key combat encounters, mostly in the final stages of the game, losing is not the end, so if you’re a reasonable human being who can draw conclusions from failure, it’s difficult to find yourself in an “unwinnable” game state.

Another thing that can influence fights in a major way are the numbers of combatants on all sides. Usually, you don’t fight alone, and there are always some bros around to lend you a hand. Their relative usefulness varies a lot, and their presence in a fight can even depend on their attitude towards your character. The same is of course true for your enemies, and while you will get into fights against single ruffians from time to time (don’t be fooled, these are often not at all easy), typically they will have advantage in numbers, sometimes even considerable, depending on how many faceless mooks come to accompany their bosses.

Now a big problem here is that during “grand fights”, enemies will often be spawned directly onto the battlefield in pre-set locations as the encounter goes on. This is most often scripted in some way, so they may spawn after a number of turns, or when a certain character is knocked out, so needless to say, it can catch you with your pants down pretty badly. Even worse, the enemy spawning is a bit clunky, especially when it’s set to trigger after the entire enemy force is wiped out. Fortunately, it’s not a critical nuisance in this game, at least it didn’t feel like one to me, but every now and again it can be rather frustrating.

Still, you can’t say that scoundrels jumping out of nowhere is ill-fitting for the wuxia theme. In fact, the wuxia-appropriate whoopass to be had in this game adds a lot of charm to the fights. Whether you stand against an unpleasant Tibetan monk who is at odds with Chinese Buddhism, or unmask an evil poisoner cook in a fancy restaurant, or take part in a competition for the title of the master swordsman, the brawls are very lively and memorable. There are many times where you will start combat with a chuckle, and continue to smile as the situation progresses.

Speaking of progress, another factor that keeps the gameplay fresh is how Tale of Wuxia keeps throwing new things at you at regular intervals. These can range from new options unlocked in education mode, new major places to visit, recurring characters growing in power, or even whole new systems and layers, like party building and an open world, which is introduced all of a sudden in the final chapter of the game!

Unfortunately, this open world kind of sucks. A lot about it feels rushed, there’s not really much to do on the overland map apart from going from place to place, and worse, most of these places you’ve already been to at this point in the game. Even worse yet, there’s not a whole lot of new content added to them, if any, before you trigger its spawning by advancing the main storyline. And by far the worst, some events influence the in-game time, or their appearance depends on it, and there’s no way of quickly passing the clock – so if some situation leaves you in the middle of nowhere at midnight, and you hate walking around in the dark, you’re sore out of luck.

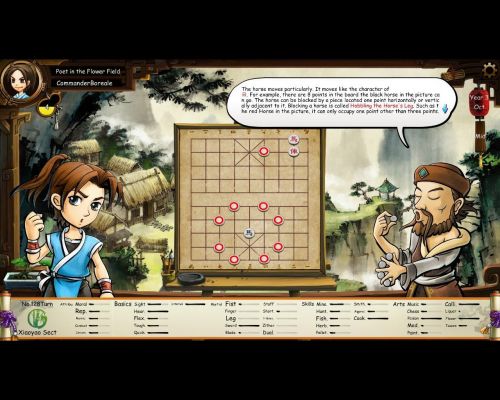

To continue with what doesn’t work too well, you also have to know that while Tale of Wuxia lets you do many things and undertake various colourful activities, most of the things that aren’t covered by CYOA sequences, combat or 3D exploration are presented in the form of minigames. These minigames are not very good. In fact, the best you can say about some of them is that they end fast, because they are as unimaginative as it can get – there’s one with matching two hidden objects, there’s one where you’re a turret shooting animals, and another one that’s literally whack-a-mole. There are more, of course, and not a single one of them really feels like it’s adding anything to the gameplay. Fortunately, and this is by far the best thing about the minigames, which ought to be stressed, is that by and large they are completely avoidable. You don’t have to partake in them if you don’t want to, except for a very few instances, and I’m not even sure if these aren’t skippable in some way as well.

However, odds are you will unwittingly expose yourself to them during the game’s tutorial/introduction, which features a starter village so horrible, so terrible it makes Hommlet look like an exciting adventure. If you end up playing Tale of Wuxia, please consider just girding your loins and powering through the starter village – it’s not going to be pleasant, and you might put yourself on the brink of ragequit (I know it happened to me), but what follows is more than worth the pain, and I can’t stress this enough.

Everybody was kung fu fighting

A few words on worldbuilding, characters and the story must be said, because this is another area where Tale of Wuxia shows a number of very well-implemented ideas.

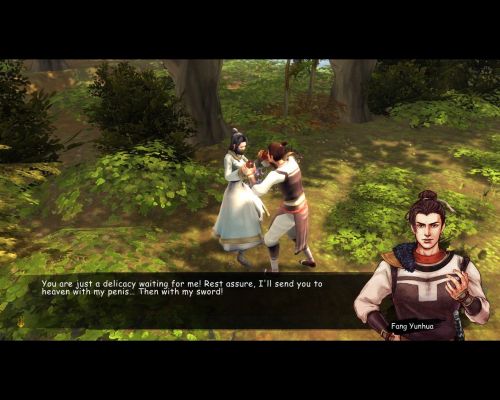

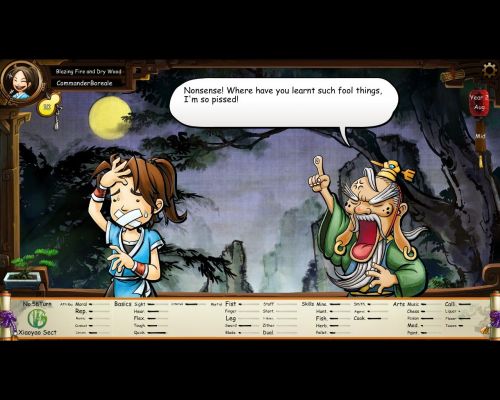

For starters, the general writing and tone of the game is very solid. For the most part, it’s pretty hilarious and tongue-in-cheek, but it also knows how to be serious when it has to be, and some of the more dramatic scenes that play out throughout the game can be fairly gripping.

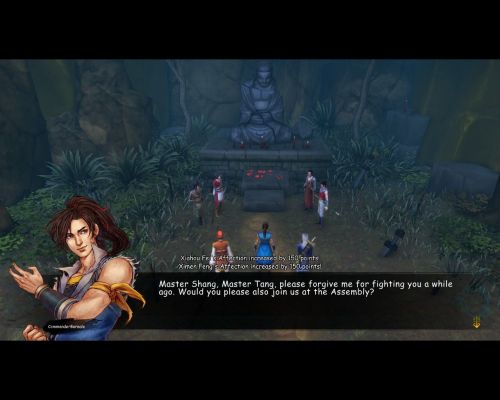

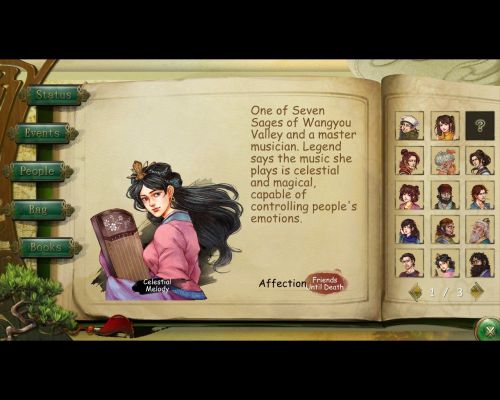

The most important part that makes the “writing” shine is the colourful cast of characters. The game doesn’t have a lot of NPCs, but they are all incredibly well fleshed-out, and even if you get lost among their similar-sounding Chinese names, you’ll soon start recognising them very easily thanks to their particular personalities and attributes. It also helps a lot that the characters have recurring roles throughout the game, and they may change from friends to foes, from allies to adversaries, or just stay on the sidelines and come along for the ride. This is yet another thing that profits tremendously from the fact that most fights in this game aren’t “lethal” – since people rarely die for real in combat, it reduces the number of “throwaway” characters to a minimum, and each time it does happen, it feels like a really big deal. It’s also fun to watch them develop and advance together with yourself as you progress through the game.

I would even go as far as saying that you become emotionally engaged with some of the major NPCs, because in the grand scheme of things they are so distinctive and prominent that you can’t not care about them. They are a bit like the Diegos and Miltens from Gothic in that sense. Interacting with them is also genuinely fun, and some of the inter-character relations are very well thought out and presented – for example, the dynamics between yourself, your fellow disciples, and your master almost always provide something memorable, whether it’s some bout of silliness, an extended sparring session, or internal struggles with envy and buried pasts.

What also adds a lot of colour to the cast is obviously the wuxia theme. Since every skill and ability is related to martial arts, this makes everyone a practitioner of kung fu, whether they are a painter, a musician, a chessmaster, a beggar or a drunkard. And again, this ties very well to the rest of the game and its themes and systems – good luck if you ever find yourself in the middle of an argument between a master painter and a calligrapher about whose discipline is better both as an art and a fighting style!

There is also a great sense of closure to your relations with certain characters as the game nears its end. Depending on the path you choose, you may find yourself put against your friends, or former friends, in combat, but this time it’ll be a fight to the death. This provokes “emotional responses” from your character, which result in very nasty debuffs. Similarly, if you have your friends as allies in those key fights, you may in turn get buffs that are almost supercharge-tier. Not to mention that the entire course of these battles may change drastically depending on your ties with certain characters. It works as an excellent practical “ending slide” of sorts for those NPCs. Because in most other games, the information whether, in the end, someone hates your guts or would go through fire and water for you would be given as some text on an ending slide. Here, your relationships and their fruits are given actual, practical significance.

As you might imagine, with so many different NPCs and with a character system so intricate, Tale of Wuxia has incredible nonlinearity. There are a number of major paths to go through in the main storyline, also with lots of branching within these paths, and a metric ton of endings, some of which are very hard to get and require you to work the entire game for them. A few are even so obscure or difficult to achieve that you could easily call them “secret”. It’s also necessary to get at least some of them to fully piece the puzzle that is the main plot – because if you go through the game once, you will only see one “side” of the story, and the significance of many of its parts will escape you completely. In this regard, Tale of Wuxia is sort of similar to Age of Decadence – you have to make an effort to figure out what’s going on.

Though some more light can be shed on the story through the unlockable prologue. It consists of a few chapters that present the events that would later result in the main plot. The prologue answers a few questions and doubts you may have after finishing the game once, and each of its chapters unlocks individually as you progress through the game proper, though it beats me how that works in detail – I only realised the prologue was there after I was done with my playthrough.

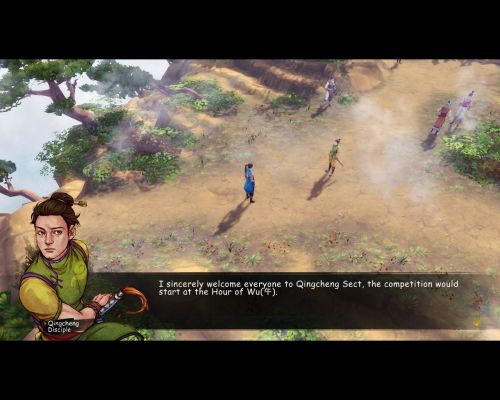

Another thing that works in favour of the story and individual events is that some of them have imposed time limits, which force you to plan ahead, choose priorities and not waste time. In the CYOA mode, this typically works by giving you a deadline for some event happening on a specific day, well in advance too. As there’s also a 3D exploration mode in the game, which for the most part, before the overland map is unlocked, puts you in big cities, time plays an important role there as well. You never spend more than a full day in a city, and the clock ticks on at its own pace in real time, whereas many side quests and such can only be triggered or accomplished before a specific hour. Some of them can also be mutually exclusive, and not only due to the strict time-frame.

Unfortunately, what can sometimes keep the writing down in a significant manner is the broken state of this game’s translation, which also gets progressively worse as it goes on. For the first half or so, the English is awkward with bouts of strangeness, and in the second half it often feels like machine translation that’s never been put through any sort of editing. It has to be said though, that the practical effect of this is most often limited to dialogues feeling weird or unintentionally comical, because the actual parts that matter (particularly for the main plot) are perfectly understandable without the need of putting too much effort into it. Unless, of course, you stumble upon dialogue nodes that are left untranslated, in Chinese. Or the dialogue options are like that. Or there’s a “puzzle” with untranslated content – bonus points if the answer is given to you explicitly because the translator gave up.

It also has a negative effect on what we might call Tale of Wuxia’s “deep lore”. Because this lore is very deep, and from what I can tell it’s primarily based on real Chinese history, folklore, religion, and of course on wuxia tales and novels. In some ways, this is actually a very cool thing, especially if you’re a stranger to the subject matter, because it still feels like it’s putting you in a whole another world, but at the same time the basis in reality makes it much more “convincing” compared to most other invented gameworlds, and some of the bits and pieces that you recognise make you feel smart, simple as that. You might even say that this game can work as a sort of Chinese Darklands thanks to this aspect.

However, the broken translation makes absorbing all this information somewhat hard at times, and even worse, when Tale of Wuxia decides to lecture you on some of the finer points of Chinese calligraphy, it becomes really really really freaking wordy. Reading the gargantuan walls of text on deep lore is already a challenge in itself, especially when there are multiple ones in quick succession, not to mention that some of them are so big that they even need to use a smaller font to fit in dialogue bubbles. But when you combine the walls of text with awkward translation, you will more often than not just fast-forward through them without reading, and that is never a good thing.

Rong Rong

Obligatory chapter on tech stuff.

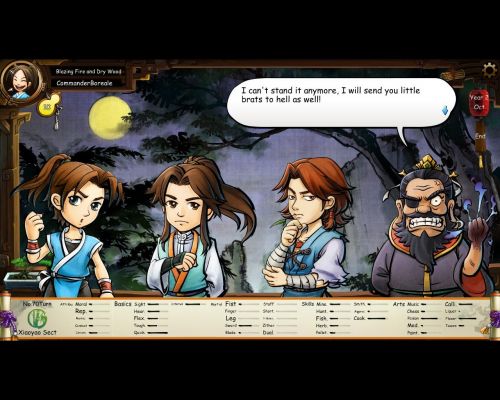

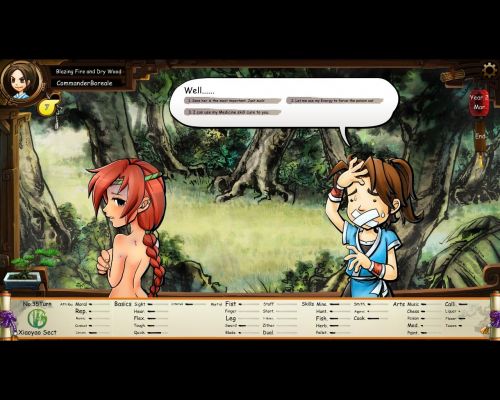

Graphics-wise, Tale of Wuxia is a mixed bag. Generally speaking, it’s divided into two big parts – the drawn CYOA interface, and the 3D exploration mode. I think the art for the CYOAs can be charming, and I like how characters have multiple “avatars” that present their various moods – it makes the otherwise static sequences much more lively and dynamic. Of course, the artstyle is very “Asian cartoony” for the lack of a better expression, so it may rub you the wrong way, and at times it really does feel a tad too weird. The 3D view on the other hand is nothing to talk about. It’s functional, I suppose, but it won’t grab any rewards for style or attractiveness.

Sounds are okay, though nothing special, but the music is very nice. It’s properly oriental, with many traditional instruments used, and though the game recycles the tunes quite often, they are pleasant enough to never really get old. The only exception is the combat theme, which is much more… modern-y and action-y, suffice to say.

I spoke before about walls of text having smaller fonts, and this is something that might be worth mentioning too. Tale of Wuxia does some technical things with the text to signal different aspects of speech or make certain characters stand out. This is mostly achieved through standard formatting measures, like different font sizes, colours, bold text, italics, etc. You might think it something obvious, but given how few games, and especially RPGs, utilise this kind of basic stuff, I figured it should be commended. Of course, the chosen basic font is less commendable, since it’s Comic Sans, and sometimes the colour-coding can get stupid, such as light yellow text on a white background, but those are fortunately rare cases.

It also has to be said that the game can be a bit rough to play, especially at the start, because of a number of minor annoyances that tend to pile up. The lack of documentation I mentioned before is one thing. Another is the fact that the UI is very clunky, and parts of it also didn’t survive translation very well – text can be all over the place or not fit tooltip windows, etc. But the most annoying things include not being able to switch fighting styles outside combat, which forces you to go through the cooldown resets for no good reason if you want to try something new or just adapt to a difficult fight, as well as not being able to reload the game in combat. Blocking saving in combat is perfectly fine, but if you want to “give up” and restart a fight that’s gone south, you pretty much have to restart the game or lose on purpose and fast-forward through the outro dialogues or whatever, and that tends to be incredibly bothersome, particularly for big, long fights.

The last thing that stuck with me when it comes to annoying bits is the “radiant AI” of some NPCs in exploration mode. As said before, there’s an in-game day/night cycle and clock, and some quests are related to the in-game time. Unfortunately, certain NPCs, including quest-givers and shopkeepers, happen to have completely unpredictable daily routines, so when you come back to a guy to finish a quest, it may turn out that he’d buggered off and is nowhere to be found. Have fun trying to look for him when you have other deadlines to attend to.

Joy be with you, dude

Tale of Wuxia took me completely by surprise. I can’t tell you what I’d expected before trying it, because I don’t think I even had any specific expectations other than “it’s probably going to be silly fun”. Suffice to say, it turned out to be much, much more than that.

I will reiterate what I said before, and I will do it with full conviction. This game has one of the best character systems I’ve ever seen in an RPG, if not the best, to the degree that it puts the vast majority of RPGs out there to complete shame. The influence character building has on combat and storytelling as well as on pure old-fashioned fun derived from the gameplay is astounding, and even more amazing is how well thought out it is, and how everything clicks together into one great package.

Because the character system is not its only advantage. The combat is exciting. The storytelling is solid. The nonlinearity is impressive. And the non-player characters are both complex and interesting.

Of course, as noted, it’s not without its problems, but their relative insignificance compared to the game’s good sides makes it easy to pay less attention to them and instead focus on what works, and what is fun.

I finished Tale of Wuxia in 34 hours, and I must say I was sad to see it end. The last chapter can drag a bit because of the awkward open world structure introduced during it, but the final fights are so damn crazy and fun, they more than make up for it, and also make you appreciate the journey as a whole. On reflection, these 30-ish hours of playtime are probably as optimal as you can get. The game ends gracefully before it can turn stale, and it leaves you with an appetite for more, which is very beneficial from the perspective of its branching plot structure and multitude of different character builds. It is definitely something I am going to come back to, and perhaps even in the very near future.

Ancient Chinese secret

Hey. Let me ask you something. Did you ever feel like your favourite RPGs suffered from a critical lack of explosive flying roundhouse kicks? Were you ever of the impression that you really missed having a calligraphy skill? And wouldn’t you agree that a zither would make for an excellent weapon?

If you answered “yes” to any of these questions, odds are you might need more wuxia in your life. It is also very likely that you haven’t heard of the one game that can satisfy all your crazy Chinese kung fu cravings. That game is called Tale of Wuxia.

It was released in 2016 by Heluo Studio from China, which is how you know that it’s the real deal and not some cheap gweilo knockoff. Though actually it’s a remake of the studio’s earlier game from 2001, known as “Legend of Wulin Heroes” (it was never released outside China, I believe), which was a tactical RPG/princess maker based on wuxia novels by the writer Jin Yong.

You’ve probably never heard of any of the names and titles mentioned in this introduction. I know I hadn’t before trying this game. Not to mention it took me years before I did give it a spin. And the only thing I can say is that I regret it took me so long to do it.

So you want to be a xia

Tale of Wuxia’s main tagline is that it “has been dedicated to providing gameplayers with a player-defined platform, where they can customize their own Wuxia” (“Wuxia” is Chinese for “martial hero”), so as you may imagine, character building is an important part of this game.

And what a platform for character building it is! When you look at the system at first, you might get suspicious, because it has all the elements that don’t work in most other games, and which lend themselves to a great many trap builds. I’m talking of course about the multitude of statistics (there are around 40 things to raise), and the fact that seemingly useless things (“tea-making”, “calligraphy”) are coupled with what looks like obviously superior options (combat stats). In another game, you’d identify the dump stats, pump your sword skill to maximum and set sail to victory.

This is not at all the case in Tale of Wuxia. Here, all the statistics, from floriculture to martial arts, are useful to some degree, for a number of reasons. For starters, most combat styles in the game scale off two abilities – a primary combat skill and a secondary skill. For example, there’s a Taoist sword-fighting style, whose effectiveness is influenced by your skill in calligraphy. Similarly, a throwing weapon style will need high chess-playing. A zither (yes, the musical instrument) fighting style requires a high score in music. So on and so forth.

Also, a word on how the styles actually work. Apart from being influenced by a primary weapon skill and a secondary support skill, they usually give you a set of three unique moves in combat, though the most basic ones may be limited to two moves. All the moves require energy (mana, more or less) to perform, while the higher-tier abilities are only unlocked when you reach enough proficiency in a given style, and they also go on cooldown when used. Switching between styles in combat is possible, but it puts all the better abilities on cooldown, so effective switching requires a modicum of planning to pull off. The move sets are all clearly focused on a specific purpose, and the abilities often work best in combos. To follow the example of the Taoist sword style – the first, basic attack gives you a mana shield, the second move buffs you with vampirism (leeching both health and energy from damaged enemies), and the third is an area-wide slash that ignores armour. Proper combination of the three can leave you almost unkillable.

The versatility and flexibility when it comes to the combinations of skills and fighting styles gives tremendous freedom and breadth to the character system. The ways of building your wuxia are numerous, and you might switch between different styles many times throughout the course of the game – whether it’s because a new one you’ve just unlocked is more powerful than what you had before, or because you got bored of the old one and want to try something different.

Furthermore, raising various skills to high levels often gives you various long-term boons. These might be unlockable choices in adventures, skill check opportunities, or entirely unique events that are triggered only at certain skill thresholds.

There’s also a nice synergy between the above aspects, as the events you unlock often serve to let you gain new combat styles, which might not even be related to the skill that triggered a given adventure. Of course, these events will also net you experience, new acquaintances, items and the like.

Another element that ties all these parts together are the “internal arts”. These are basically passive abilities that boost your character’s performance, and their functionalities vary wildly. Some simply give stat bonuses (some of which keep rising the longer combat goes on), but others are more involved, and may give you a poisoning aura, let you move freely through enemy zones of control, periodically remove debuffs, etc.

Obviously the final piece of the puzzle that makes the system whole is equipment. You don’t get to play dress-up too much in Tale of Wuxia, as you can only have three items equipped at a time (a weapon, an armour, an accessory), but the bonuses they provide are still significant. Apart from the obvious features like boosting your attack and defence, your gear will also grant you additional abilities, which are not unlike the internal styles.

When you combine all these parts – stats, combat styles, internal arts and equipment – you can get so many, so different character builds and playstyles, it’s honestly almost overwhelming. You can mould your character into an unbreakable, ever-regenerating bulldozer, an artful dodger, a toxic avenger, a mass-slicer and dicer, Cacofonix, a ranged pinner and kiter, an immortal swordsman, a fan-slapping paralyser… and more. Or combinations thereof. It’s completely crazy, and it’s unlike anything I’ve seen in an RPG.

It is without doubt one of the best character systems I’ve ever had the pleasure to witness, if not the best. All the elements are in perfect synergy. There are no dump stats. The number of possible character builds is impossible to give, and getting them running is extremely satisfying. And most importantly, all the aspects come to a very elegant meeting in combat, which is the real meat and focus of the game, while also remaining relevant outside of it. I don’t know how much time and planning it must have taken the developers to establish this monster of a system, but I can give them the greatest praise for pulling it off.

With all that said, you might still be wondering how the character building process actually works in practice. This is also fairly interesting. As you start the game, your stats are all randomly rolled, and you have no influence whatsoever on this, apart from rerolling everything from scratch. The character generator also assigns three random traits to your character, which define your personality or attitude towards others – you might be chivalrous, which gives additional damage based on your “morality” stat, or smart, which makes you focus better on complex tasks, or nimble, which ups your dodge rating, and so on.

After that, the vast majority of your stat gains will be achieved through an “education” interface that is similar to all assorted princess maker games. It’s basically a choose-your-own-adventure layer that lets you train, stroll around in search of trouble, craft items and meet other people. This might sound simple and unexciting, but suffice to say – character building builds character.

That is because you have to balance a ton of things during the education mode. Obviously there’s training, which raises your very important stats. But that won’t let you unlock most of the good stuff that is “hidden” in the various events that you come across while strolling. However, skipping training like that will anger your master, which means you’ll have to do chores around the martial arts school every now and again to gain his affection back. It’s also important to keep high relations with most of the other characters you meet, especially your fellow disciples, since this can have huge consequences on how events, primary and secondary, may progress. Then there’s your character’s mood, which drops or improves depending on what tasks he finds boring, and which influences your experience gain. And finally, all these activities take stamina to perform, and your stamina pool for every “time period” during education is severely limited.

Obviously, during education you won’t be going only through CYOAs, as the phase is generously interspersed with various combat encounters or long excursions into cities. The most important aspect of these, apart from breaking any monotony that might arise from pressing the “train toughness” button too many times, is that these encounters let you put your character to the test, and give you great feedback on what you’re doing right or wrong. The game might be brutal if you build your character badly, but it gives you ample time and opportunity to identify your mistakes and correct them as necessary. Which is also very welcome, because for a longer while the complexity of the character system can simply leave you overwhelmed and confused. So every time you get stomped, it gives you another occasion for drawing conclusions.

Tale of Whoopass

With all this character building done, it’s time to discuss how the other major part of the game works. The part where you perform blazing somersaults to knock out evil henchmen and other ne’er-do-wells.

The combat engine in Tale of Wuxia is pretty standard when you look at the big picture. It’s turn-based, there’s a hex-grid, a bunch of combatants, each of them is limited to one move and one action per turn, etc. Every character has a pool of health (which can range from 1000 to 25000, so we’re talking big numbers), and depleting it means getting knocked out of the fight. They also have energy (“mana/stamina”, as mentioned before), which is required to take any action in combat, and whose management can be fairly important for low-cooldown/high-energy cost movesets, because if it goes down too much, you won’t be able to act at all. And of course there’s movement, which determines how many hexes you can cross a turn (it ranges from 1 to 5).

Characters have a number of secondary stats as well, which are no less important to how combat flows. Evasion lets you dodge attacks, counter lets you respond to attacks with free ones of your own, critical rate is obvious and so is accuracy. You also have percentage reductions to the opponent’s critical and counter rates, as well as a general defence stat for a flat damage reduction.

Overall, the system may look generic, but it serves as a solid foundation for interplay between special abilities, enemy composition, tactical opportunities and prayers to the gods of dice. And Tale of Wuxia makes use of this in very good, sometimes even spectacular, ways.

The true core of this game’s combat is putting your character build into practice and watching how ridiculously strong of a combo you’ve managed to devise. The dozens of special abilities available to you through internal arts and fighting styles make for a very exciting brew, particularly when you combine them with min-maxed ability scores that further serve to define your combat performance. Going for a poison-focused build lets you simply stand around and watch everyone get sapped of health and energy alike until they drop down and die. Pumping counter and combining it with an appropriate style will let you counterattack almost every time, while simultaneously accumulating critical chance. Pumping dodge may be risky, but it can also result in effective invulnerability.

However, all these combinations, and then some, are also available to your enemies, and you may find one day that your immovable object meets an unstoppable force. If you stumble upon enemies who more or less hard counter you, or are able to disable one of the key components of your build, it’s time to start improvising. Fortunately, given how you’ll usually develop your character along multiple branches, if you think hard enough, you may still find an ace up your sleeve that might just carry you through whatever hard fight that’s giving you trouble, even if it’s not as strong on paper as your “default” style.

But there is one big issue about all these abilities, mechanics and sub-mechanics. Namely that some of them are very obscure and can be figured out largely by accident, some don’t match when it comes to their descriptions and actual effects, and some others still have names so very vague or uninformative, you’ll never guess what they do before trying them out (e.g. would you ever consider that “Teleportation Walk” is a buff that reflects incoming damage back at enemies?), especially since the game is pretty bad when it comes to documentation. There is no manual, the pop-up tooltips aren’t always very helpful, and the general state of English can be pretty damn broken, but more on this later. So in other words, be prepared to experiment a lot. Or find a guide on the Internet that has all the abilities and effects listed, if only for quick reference.

Nevertheless, to come back to the previous point, hard fights in this game are really plentiful. The best part perhaps is that Tale of Wuxia keeps ramping up the difficulty all the time, sometimes even to ridiculous degrees, just to keep you on your toes and remind you that there are always bigger fish out there. I would say there are a few “chokepoints” here, whose sole purpose is to encourage you to keep practising and making your character stronger. Each time during my playthrough when I thought I had achieved “god status”, and could not possibly imagine having trouble in a fight ever again, Tale of Wuxia then decided to show me how terribly wrong I was. And perhaps the best thing about this approach is that the vast majority of lost fights don’t lead to game over. You’ll still typically miss out on a lot of rewards and such, but apart from key combat encounters, mostly in the final stages of the game, losing is not the end, so if you’re a reasonable human being who can draw conclusions from failure, it’s difficult to find yourself in an “unwinnable” game state.

Another thing that can influence fights in a major way are the numbers of combatants on all sides. Usually, you don’t fight alone, and there are always some bros around to lend you a hand. Their relative usefulness varies a lot, and their presence in a fight can even depend on their attitude towards your character. The same is of course true for your enemies, and while you will get into fights against single ruffians from time to time (don’t be fooled, these are often not at all easy), typically they will have advantage in numbers, sometimes even considerable, depending on how many faceless mooks come to accompany their bosses.

Now a big problem here is that during “grand fights”, enemies will often be spawned directly onto the battlefield in pre-set locations as the encounter goes on. This is most often scripted in some way, so they may spawn after a number of turns, or when a certain character is knocked out, so needless to say, it can catch you with your pants down pretty badly. Even worse, the enemy spawning is a bit clunky, especially when it’s set to trigger after the entire enemy force is wiped out. Fortunately, it’s not a critical nuisance in this game, at least it didn’t feel like one to me, but every now and again it can be rather frustrating.

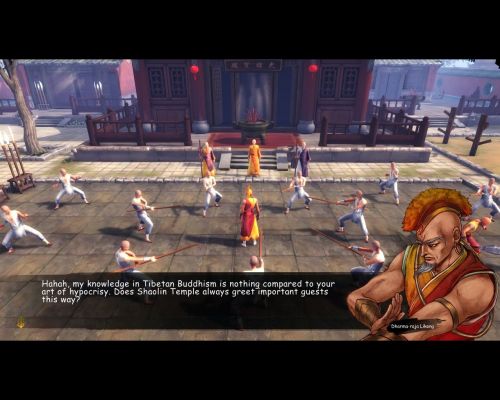

Still, you can’t say that scoundrels jumping out of nowhere is ill-fitting for the wuxia theme. In fact, the wuxia-appropriate whoopass to be had in this game adds a lot of charm to the fights. Whether you stand against an unpleasant Tibetan monk who is at odds with Chinese Buddhism, or unmask an evil poisoner cook in a fancy restaurant, or take part in a competition for the title of the master swordsman, the brawls are very lively and memorable. There are many times where you will start combat with a chuckle, and continue to smile as the situation progresses.

Speaking of progress, another factor that keeps the gameplay fresh is how Tale of Wuxia keeps throwing new things at you at regular intervals. These can range from new options unlocked in education mode, new major places to visit, recurring characters growing in power, or even whole new systems and layers, like party building and an open world, which is introduced all of a sudden in the final chapter of the game!

Unfortunately, this open world kind of sucks. A lot about it feels rushed, there’s not really much to do on the overland map apart from going from place to place, and worse, most of these places you’ve already been to at this point in the game. Even worse yet, there’s not a whole lot of new content added to them, if any, before you trigger its spawning by advancing the main storyline. And by far the worst, some events influence the in-game time, or their appearance depends on it, and there’s no way of quickly passing the clock – so if some situation leaves you in the middle of nowhere at midnight, and you hate walking around in the dark, you’re sore out of luck.

To continue with what doesn’t work too well, you also have to know that while Tale of Wuxia lets you do many things and undertake various colourful activities, most of the things that aren’t covered by CYOA sequences, combat or 3D exploration are presented in the form of minigames. These minigames are not very good. In fact, the best you can say about some of them is that they end fast, because they are as unimaginative as it can get – there’s one with matching two hidden objects, there’s one where you’re a turret shooting animals, and another one that’s literally whack-a-mole. There are more, of course, and not a single one of them really feels like it’s adding anything to the gameplay. Fortunately, and this is by far the best thing about the minigames, which ought to be stressed, is that by and large they are completely avoidable. You don’t have to partake in them if you don’t want to, except for a very few instances, and I’m not even sure if these aren’t skippable in some way as well.

However, odds are you will unwittingly expose yourself to them during the game’s tutorial/introduction, which features a starter village so horrible, so terrible it makes Hommlet look like an exciting adventure. If you end up playing Tale of Wuxia, please consider just girding your loins and powering through the starter village – it’s not going to be pleasant, and you might put yourself on the brink of ragequit (I know it happened to me), but what follows is more than worth the pain, and I can’t stress this enough.

Everybody was kung fu fighting

A few words on worldbuilding, characters and the story must be said, because this is another area where Tale of Wuxia shows a number of very well-implemented ideas.

For starters, the general writing and tone of the game is very solid. For the most part, it’s pretty hilarious and tongue-in-cheek, but it also knows how to be serious when it has to be, and some of the more dramatic scenes that play out throughout the game can be fairly gripping.

The most important part that makes the “writing” shine is the colourful cast of characters. The game doesn’t have a lot of NPCs, but they are all incredibly well fleshed-out, and even if you get lost among their similar-sounding Chinese names, you’ll soon start recognising them very easily thanks to their particular personalities and attributes. It also helps a lot that the characters have recurring roles throughout the game, and they may change from friends to foes, from allies to adversaries, or just stay on the sidelines and come along for the ride. This is yet another thing that profits tremendously from the fact that most fights in this game aren’t “lethal” – since people rarely die for real in combat, it reduces the number of “throwaway” characters to a minimum, and each time it does happen, it feels like a really big deal. It’s also fun to watch them develop and advance together with yourself as you progress through the game.

I would even go as far as saying that you become emotionally engaged with some of the major NPCs, because in the grand scheme of things they are so distinctive and prominent that you can’t not care about them. They are a bit like the Diegos and Miltens from Gothic in that sense. Interacting with them is also genuinely fun, and some of the inter-character relations are very well thought out and presented – for example, the dynamics between yourself, your fellow disciples, and your master almost always provide something memorable, whether it’s some bout of silliness, an extended sparring session, or internal struggles with envy and buried pasts.

What also adds a lot of colour to the cast is obviously the wuxia theme. Since every skill and ability is related to martial arts, this makes everyone a practitioner of kung fu, whether they are a painter, a musician, a chessmaster, a beggar or a drunkard. And again, this ties very well to the rest of the game and its themes and systems – good luck if you ever find yourself in the middle of an argument between a master painter and a calligrapher about whose discipline is better both as an art and a fighting style!

There is also a great sense of closure to your relations with certain characters as the game nears its end. Depending on the path you choose, you may find yourself put against your friends, or former friends, in combat, but this time it’ll be a fight to the death. This provokes “emotional responses” from your character, which result in very nasty debuffs. Similarly, if you have your friends as allies in those key fights, you may in turn get buffs that are almost supercharge-tier. Not to mention that the entire course of these battles may change drastically depending on your ties with certain characters. It works as an excellent practical “ending slide” of sorts for those NPCs. Because in most other games, the information whether, in the end, someone hates your guts or would go through fire and water for you would be given as some text on an ending slide. Here, your relationships and their fruits are given actual, practical significance.

As you might imagine, with so many different NPCs and with a character system so intricate, Tale of Wuxia has incredible nonlinearity. There are a number of major paths to go through in the main storyline, also with lots of branching within these paths, and a metric ton of endings, some of which are very hard to get and require you to work the entire game for them. A few are even so obscure or difficult to achieve that you could easily call them “secret”. It’s also necessary to get at least some of them to fully piece the puzzle that is the main plot – because if you go through the game once, you will only see one “side” of the story, and the significance of many of its parts will escape you completely. In this regard, Tale of Wuxia is sort of similar to Age of Decadence – you have to make an effort to figure out what’s going on.

Though some more light can be shed on the story through the unlockable prologue. It consists of a few chapters that present the events that would later result in the main plot. The prologue answers a few questions and doubts you may have after finishing the game once, and each of its chapters unlocks individually as you progress through the game proper, though it beats me how that works in detail – I only realised the prologue was there after I was done with my playthrough.

Another thing that works in favour of the story and individual events is that some of them have imposed time limits, which force you to plan ahead, choose priorities and not waste time. In the CYOA mode, this typically works by giving you a deadline for some event happening on a specific day, well in advance too. As there’s also a 3D exploration mode in the game, which for the most part, before the overland map is unlocked, puts you in big cities, time plays an important role there as well. You never spend more than a full day in a city, and the clock ticks on at its own pace in real time, whereas many side quests and such can only be triggered or accomplished before a specific hour. Some of them can also be mutually exclusive, and not only due to the strict time-frame.

Unfortunately, what can sometimes keep the writing down in a significant manner is the broken state of this game’s translation, which also gets progressively worse as it goes on. For the first half or so, the English is awkward with bouts of strangeness, and in the second half it often feels like machine translation that’s never been put through any sort of editing. It has to be said though, that the practical effect of this is most often limited to dialogues feeling weird or unintentionally comical, because the actual parts that matter (particularly for the main plot) are perfectly understandable without the need of putting too much effort into it. Unless, of course, you stumble upon dialogue nodes that are left untranslated, in Chinese. Or the dialogue options are like that. Or there’s a “puzzle” with untranslated content – bonus points if the answer is given to you explicitly because the translator gave up.

It also has a negative effect on what we might call Tale of Wuxia’s “deep lore”. Because this lore is very deep, and from what I can tell it’s primarily based on real Chinese history, folklore, religion, and of course on wuxia tales and novels. In some ways, this is actually a very cool thing, especially if you’re a stranger to the subject matter, because it still feels like it’s putting you in a whole another world, but at the same time the basis in reality makes it much more “convincing” compared to most other invented gameworlds, and some of the bits and pieces that you recognise make you feel smart, simple as that. You might even say that this game can work as a sort of Chinese Darklands thanks to this aspect.

However, the broken translation makes absorbing all this information somewhat hard at times, and even worse, when Tale of Wuxia decides to lecture you on some of the finer points of Chinese calligraphy, it becomes really really really freaking wordy. Reading the gargantuan walls of text on deep lore is already a challenge in itself, especially when there are multiple ones in quick succession, not to mention that some of them are so big that they even need to use a smaller font to fit in dialogue bubbles. But when you combine the walls of text with awkward translation, you will more often than not just fast-forward through them without reading, and that is never a good thing.

Rong Rong

Obligatory chapter on tech stuff.

Graphics-wise, Tale of Wuxia is a mixed bag. Generally speaking, it’s divided into two big parts – the drawn CYOA interface, and the 3D exploration mode. I think the art for the CYOAs can be charming, and I like how characters have multiple “avatars” that present their various moods – it makes the otherwise static sequences much more lively and dynamic. Of course, the artstyle is very “Asian cartoony” for the lack of a better expression, so it may rub you the wrong way, and at times it really does feel a tad too weird. The 3D view on the other hand is nothing to talk about. It’s functional, I suppose, but it won’t grab any rewards for style or attractiveness.

Sounds are okay, though nothing special, but the music is very nice. It’s properly oriental, with many traditional instruments used, and though the game recycles the tunes quite often, they are pleasant enough to never really get old. The only exception is the combat theme, which is much more… modern-y and action-y, suffice to say.

I spoke before about walls of text having smaller fonts, and this is something that might be worth mentioning too. Tale of Wuxia does some technical things with the text to signal different aspects of speech or make certain characters stand out. This is mostly achieved through standard formatting measures, like different font sizes, colours, bold text, italics, etc. You might think it something obvious, but given how few games, and especially RPGs, utilise this kind of basic stuff, I figured it should be commended. Of course, the chosen basic font is less commendable, since it’s Comic Sans, and sometimes the colour-coding can get stupid, such as light yellow text on a white background, but those are fortunately rare cases.

It also has to be said that the game can be a bit rough to play, especially at the start, because of a number of minor annoyances that tend to pile up. The lack of documentation I mentioned before is one thing. Another is the fact that the UI is very clunky, and parts of it also didn’t survive translation very well – text can be all over the place or not fit tooltip windows, etc. But the most annoying things include not being able to switch fighting styles outside combat, which forces you to go through the cooldown resets for no good reason if you want to try something new or just adapt to a difficult fight, as well as not being able to reload the game in combat. Blocking saving in combat is perfectly fine, but if you want to “give up” and restart a fight that’s gone south, you pretty much have to restart the game or lose on purpose and fast-forward through the outro dialogues or whatever, and that tends to be incredibly bothersome, particularly for big, long fights.

The last thing that stuck with me when it comes to annoying bits is the “radiant AI” of some NPCs in exploration mode. As said before, there’s an in-game day/night cycle and clock, and some quests are related to the in-game time. Unfortunately, certain NPCs, including quest-givers and shopkeepers, happen to have completely unpredictable daily routines, so when you come back to a guy to finish a quest, it may turn out that he’d buggered off and is nowhere to be found. Have fun trying to look for him when you have other deadlines to attend to.

Joy be with you, dude

Tale of Wuxia took me completely by surprise. I can’t tell you what I’d expected before trying it, because I don’t think I even had any specific expectations other than “it’s probably going to be silly fun”. Suffice to say, it turned out to be much, much more than that.

I will reiterate what I said before, and I will do it with full conviction. This game has one of the best character systems I’ve ever seen in an RPG, if not the best, to the degree that it puts the vast majority of RPGs out there to complete shame. The influence character building has on combat and storytelling as well as on pure old-fashioned fun derived from the gameplay is astounding, and even more amazing is how well thought out it is, and how everything clicks together into one great package.

Because the character system is not its only advantage. The combat is exciting. The storytelling is solid. The nonlinearity is impressive. And the non-player characters are both complex and interesting.

Of course, as noted, it’s not without its problems, but their relative insignificance compared to the game’s good sides makes it easy to pay less attention to them and instead focus on what works, and what is fun.

I finished Tale of Wuxia in 34 hours, and I must say I was sad to see it end. The last chapter can drag a bit because of the awkward open world structure introduced during it, but the final fights are so damn crazy and fun, they more than make up for it, and also make you appreciate the journey as a whole. On reflection, these 30-ish hours of playtime are probably as optimal as you can get. The game ends gracefully before it can turn stale, and it leaves you with an appetite for more, which is very beneficial from the perspective of its branching plot structure and multitude of different character builds. It is definitely something I am going to come back to, and perhaps even in the very near future.