RPG Codex Review: Disco Elysium

RPG Codex Review: Disco Elysium

Codex Review - posted by Infinitron on Tue 5 November 2019, 16:03:47

Tags: Disco Elysium; ZA/UM[Review by bataille]

Fear and Trembling

When I first came upon a short description of Disco Elysium in 2016, I couldn’t help but feel nostalgic. A lot about it reminded me of my college years: from the ambition to change the world to the whiff of highly metaphysical alcoholism that usually accompanies designs so grand. I pictured: scruffy-haired young men in ill-fitting blazers and their makeup-averse amicas, all of them choking on cigarette smoke in a bohemian cafe slash cheap diner. They’re trying to arrive at a hard conclusion: is Kant shit? What about that pompous blowhard Hegel? And when the conversation becomes a bit too heated for the Monday afternoon, someone exclaims: Sartre is the shittiest of them all! Everybody laughs, nods in agreement, and the discussion is taken in another, seemingly unrelated direction.

Having played through the game, I can say that this first impression was both right and wrong. What the mise-en-scène lacked was a board game or two, a pocketful of D&D campaign notes, maybe a pair of loaded *cursed* dice. The unmistakable quixotic aspirations were there. Lots of them.

Disco Elysium is the anxiety-driven, doubt-ridden, schizopolitan brainchild of an Estonian studio called, a bit arrogantly, ZA/UM. In the video game terms, it resembles an RPG/adventure with an unusually strong emphasis on narrative, character study, and failing at life, spectacularly. Dungeon crawling, epic adventuring, kobold-slaying: all of it is cast aside in favour of the exquisitely penned world-building, characterization, and human interaction. Its ambition is no less than an attempt to break out of the standard Skinner box cRPG structure and probe at what lies beyond that particular pleasure principle. If that sounds imposing, boring, or discouraging, then I’d say it’s a call to arms - this disco groove may prove deeply therapeutic for a soul made coarse by the endless stream of inconsequential power fantasies and colourful yet insipid distractions.

The smallest church in Saint-Saëns

Instead of giving us the usual freedom to become a soon-heroic, god-chosen nobody, Disco Elysium puts the player in the tear-and-alcohol-soaked shoes of a particular *somebody*. That somebody has a name, a face (sort of), a semblance of life, and a long history of destructive self-abuse, all of which slowly resurface during the course of the game.

While it may seem somewhat restrictive to disallow self-insertion in a cRPG, it helps the story to focus on the inner turmoil of our character as much as on the people and events that surround him. After all, the game’s original title used to be No Truce With The Furies, and that alone illustrates pretty well how important it must have been for the authors to have a singular ruined soul at the epicenter of the narrative. Since one obviously cannot construct effective personal drama for all possible player avatars (the only guaranteed common trait being player agency), the authors made the furies torment our hero through his prior life. It’s one of the instances where Disco Elysium’s PC-centric pen-and-paper origins shine through and affect the standard cRPG conventions. The scope is narrower but more focused, intimate, intense. A bit like that other text-heavy RPG with a set protagonist.

To dial it back a little and return us to the dimension of *computer* role-playing games and their freedom to play as whomever thou wilt, ZA/UM employs an obscure literary trope known as “total retrograde amnesia.” Or was it a selective memory wipe? A mere pretense fueled by shame? Repressed memories? Something more supra-natural? The reason for blanking out is up to the player to establish later down the line. Whatever the cause, only our past is set in stone, and it is for us to decide what kind of person we will become by the time all hell inevitably breaks loose.

The first step on the path of self-discovery is to distribute 8 points between the four main attributes: intelligence, psyche, physique, and motorics. Each attribute governs 6 thematically appropriate skills that may range from something as simple as Logic or Endurance to the more esoteric Inland Empire and Shivers. I highly recommend everyone to read their full descriptions, even if you don’t plan on investing in some of the skills. Besides providing clues and tips on what attributes to pick for certain archetypes, they’re simply a joy to read.

What really stands out when you start familiarizing yourself with the skills is how difficult it may be to fit some of them into the existing RPG categories. It takes a bit of time with the game to truly get what Esprit de Corps is really about, for example. What do Shivers actually do? What’s the difference between Drama and Suggestion? The skill selection might be the player’s first encounter with the experimental side of Disco Elysium, a sign of things to come. It only gets weirder - and sadder.

After a binge of world-ending proportions, our nameless, featureless, and pantsless hero wakes up on the floor, in a room, in a city, on a continent; all of them totally unknown and mysterious (except maybe the floor). How does one proceed under such arcane circumstances? By initiating an inner monologue of course! But who does the talking? Your skills, my liege. Depending on your choices during character creation, it may be Inland Empire lamenting that we didn’t get to see what was on the other side of the killer debauch, or Logic trying to piece something together from what little information about our current situation we have, or Pain Threshold welcoming the anguish that comes with being alive. They start talking when you regain some of your higher cognitive faculties and don’t shut up until the credits roll.

The easiest way to understand how you interact with your skills is to imagine the bicameral mind and-- that’s it, actually. That is exactly how it’s done. The player is in control of what the cop (ah, that’s one mystery solved) says and does, and your skills do most of the background thinking, guiding you to failure and regret (and an occasional triumph).

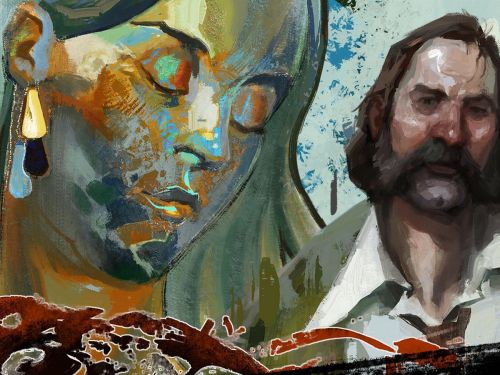

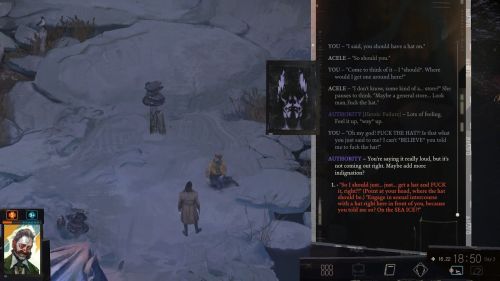

Oddly enough, each of them has a distinct personality and a... portrait. In a lesser RPG, these could have been templates for the player’s potential party members. They’re chatty, opinionated, and, most importantly, often fallible. Half Light, the mix of a psychotic barbarian and a scaredy-cat which is supposed to represent your fight-or-flight response and vigilance in the face of danger, will misjudge the gravity of a situation as often as assess one correctly. Despite its strong-willed facade, Authority often acts as a feeble sleazeball that tries to exploit its position in the warrior caste and use it as a lever to subjugate other people and get RESPECT. Conceptualization is just a third year humanities student always looking for opportunities to turn life into a living canvas. Fair enough. 24 almost-people to see you through this week-long hangover.

Not all skills are created equal, though, and some of them lack a particular “bang,” be it their practical application or even the number of times they’re used. Savoir Faire and Pain Threshold rarely if ever pop up. A couple of others mostly just produce flavour text (which is barely criticism in Disco’s case). The skills, however, are grouped in such a way that every attribute has bread-and-butter and novelty skills alike, so you don’t need to worry: if you heavily specialize in an attribute, you’ll always have friends like Rhetoric or Suggestion to steer you to excellence.

My personal uncontested favourite is Inland Empire. Aptly named after a David Lynch film, it’s a skill that’s for the most part concerned with the otherness of everyday phenomena, Jungian shadow, and ontological rifts in reality. It has an appetite for everything mysterious, unexplained, weird, and hidden from the uninitiated. Inland Empire always chimes in when a door, a threshold, or a transitory state comes up; it’s the part of your psyche that wonders what’s hidden on the dark side of the Moon. The writers themselves are obviously in love with both the skill and what it stands for as Inland Empire directly engages with some of the central themes and events of the story in a particularly meaningful way. If you’re dead set on finally catching up with the everfleeting Miracle, you probably should pick Inland Empire as your signature skill, giving it the little crown it deserves.

Unlike a myriad of hidden (and static) skill checks that provide information and insight, obstacles and conflicts in Disco Elysium are usually resolved with a dice roll. To determine whether you conquer a challenge or not, an invisible game master rolls 2d6, adds your skill value to the result, and compares it against the difficulty rating. Some of them are one-time opportunities while others can be retried at a later point in the game. The challenges themselves range in scale and daring: from raising your hand to pick up an article of clothing to actively unveiling humanity-defining existential mysteries. It’s not necessary to pass them all to get to the end, so you probably shouldn’t feel bad about failing some. Besides, your failures more often than not bring about such spectacular, grotesque, or simply funny results that you can’t help but roll with them.

Another curious part of the character-building system is the Thought Cabinet. While you explore the oneiric gameworld and interact with its aborigines, a thought (or ten) may be born of your actions, words, attitudes. In a curious display of self-awareness, the cop puts the fruit of his experiences in a mental trunk where it’s kept in relative safety until he’s finally ready to internalise it. Naturally, coming to terms with a mode of thinking and *really* making it your own takes time and effort. The rigidity of this process subjects us to various thematically appropriate maluses: incoherent ramblings are a known side-effect of becoming the harbinger of end times. But even when it’s done, and there is no escaping Revacholian Nationhood squatting inside your brain-box 24/7, the adverse effects of *thinking* will not let go; they’ll merely mutate. On the bright side, there’s always something positive about being eaten alive by your own thought process, so every bit of wisdom yields a reward of some sort upon its internalisation (be it XP rewards for your spontaneous bouts of creativity, the heightened effects of a drug, or simple skill bonuses).

Much like the skills, thoughts are beautifully illustrated, except the portraits give way to more complex surrealist vignettes. Interestingly enough, the vignettes are not separate drawings: each of them is the part of a gigantic, intricate, and surprisingly visionary mural of intertwining chimeras.

Infinite Comedy

Unresolved police business. Property damage. The suspicious demeanor of a disco woman. A stuffed bird, posthumously injured in a drunken stupor. Problems rapidly pile up once we step out of our hotel room. The cafeteria manager is angry with us: we trashed his joint the night before, and apparently there’s a dead man hanging from a noose out back, stinking up the place. He points to the exit. A man in an orange bomber jacket, hands behind his back, is casting expectant glances in our direction. Maybe he knows who - or what - we are? Noticing bottles of spirits lining the shelves, Electrochemistry, our inner sex and drugs connoisseur, sings odes to narcotic substances and urges us to have some. Cut it out, it’s not the right time. Or is it?

The bomber turns out to be our new partner, Kim Kitsuragi, a mild-mannered, reserved, secretly stoic, and somewhat anal officer of the Revachol Citizen’s Militia, or the RCM for short. We, however crazy that may sound, are an RCM officer as well, albeit from a different precinct. Some days ago a security guard was lynched in Martinaise, and we were sent by the station to investigate - four days after the fact. Locals say he has been hanging from a tree for a week. But wait a second, what is Revachol? Martinaise? People keep mentioning these places like they are supposed to ring a bell. And shouldn’t a cop have a badge?

The amnesia angle of the story is framed so vividly it’s intoxicating. It’s impossible not to feel the cop’s sheer vertigo and confusion when he’s confronting the unknown, a world that seems more an etheric plane than a tangible place. Luckily for us, Kim and an ensemble of supporting characters are patient enough to guide us through the initial shock and give us a couple of pointers along the way. With a thorough reality low-down hours away, we don’t have a choice but to cope and do our job. Outside the hotel, streaks of cold rain anoint our swollen face. A sorrowful instrumental song begins playing; a tune so foreboding and melancholic it’d give Godspeed You! Black Emperor a run for their money. Standing in the rain, the cop takes a deep breath and lets Shivers take hold. His vision crystallizes. Martinaise is the ailing harbour district of the city of Revachol. It’s been 50 years since the Revolution failed, and a foreign offensive left the district in both ruins and economic servitude. Buildings are crumbling, shell craters and bullet holes riddle the waterfront. The other side of the river is dotted with rustic fisherman’s shacks. 6000 kilometers to the north, the world is ending. The Pale is encroaching on the oecumene.

As strange as it may sound, Elysium is a game about hauntings. The deserted streets of Martinaise and its collapsing houses are sparsely populated by odd, out-of-time characters, whose presence almost intrudes on this apocalyptic timescape. René, a former royalist soldier, spends his days in the shadow of the Revolution and its folly; he’s fully uniformed, grumpy, and completely unable to leave his past behind. Then there’s Lena, the life partner of a certain cryptozoologist, who still believes in and chases after a miracle she encountered decades ago. Or a vanished university student whose abandoned apartment sits unnoticed in a dusty hallway. The traces of his obsession with the life, ideas, and suicide of Kras Mazov, the father of Communism, are all that’s left of him. An empty flat haunted by the print of a young man obsessed with the ghost of a theoretician killed by a dream. A hauntological matryoshka doll of apparitions! Not to mention an entire commercial area that is apparently besieged by the spirits from a bygone era, some of whom still roam its intercom lines. It is in our cop’s heart, however, where the rattle of spectral chains is the loudest. The disco writers’ preoccupation with the past lingering in the present is truly fascinating. Any possible future seems thoroughly cancelled. The past stays unresolved indefinitely. 28 years until the final and decisive end of history.

But of course, it’s only one side of the 1 reál coin. It wouldn’t be possible to survive the wasteland if not for Dionysus’ wine. Disco is all about empathy, connection (as shallow and fragile as it may be), and anodic dance vibes. A feast in time of death is a feast nonetheless. Don’t get me wrong, in Disco, there’s plenty of life, laughter, and the inebriation they bring. The characters stave off The Pale as best they can, and it’s a heartwarming performance indeed. The ghosts, though… there’s too many of them. They are more prominent, they wail louder and chill you deeper. Their ghoulish touch is what you’ll feel long after the curtains have been drawn.

Arguably, Disco Elysium’s greatest achievement is how almost uncannily organic the way in which the subtext is woven into the narrative is. Its ability to paint on both literal and allegorical levels simultaneously deserves a warm applause. Sure, it misfires a couple of times, but that barely detracts from the finesse on display. A comparison with Latin American magical realism would be quite trite, but that’s what it feels like for the most part. Symbolic meaning can be casually and mostly effortlessly assigned to the different parts of the text. The end result is a nifty and tight second layer of meaning that complements the main textual stratum. Although it’s worth noting that it might not always be optional. I can see how some players may feel unsatisfied with the story’s resolution if they don’t engage in a bit of critical reading at the end. But again, the fantastic elements are contextualised well enough to make sense even when taken at face value.

It’s tempting to characterize Disco as a metamodernist game. In the main bulk of its writing, it manages to almost entirely avoid irony and postmodern distance in favor of earnestness and openness. The text is rarely if ever bastardised by the shopworn collage and intertextual techniques. But it’s not entirely naive either: it’s fully conscious of the historical context in which it was created, and yet it isn’t held back by the knowledge. The authors aren’t afraid to coin a plethora of unusual composite words (Zaum, but not really), to meaningfully employ music and art to enhance the impact of their litterae, to push the envelope until they bleed and their hearts give out. Wisely, the grotesque pomo abominations are kept in a pen and only let out to serve the goals of New Sincerity. A metafictional subplot is a curious divergence from the ethos, not the norm. Of the new and old, the former reigns supreme.

It’d be less painful to let go: she has long turned her back on you. But who could muster the courage to do so?

Seize the means of representation

Existentialism as a creative modus is inherently politically neutral, and Disco’s writers don’t seem to have qualms with the fact (at least on the surface). Political themes mainly serve as a backdrop, and the player’s four possible political affiliations-communism, fascism, ultraliberalism (wheeze), moralism-are played for laughs. Consciously avoiding the unsavory label of agitprop (surely, ideologically supercharged RPGs should be classified as torture devices), ZA/UM often presents the entire spectrum in an exaggerated, even comical manner. Prepare for your inner communist to be a walking cliché that ceaselessly rants about the plight of the working class, the fangs on those capitalist superpredators, and the inevitable redistribution of their wealth. From the half-opposite side of the political compass you’ll hear the fascist’s colourful tirades about immigrants ruining everything and the onset of a plague of civilization-destroying degeneracy. Only radical centrists are going to enjoy the lulling peace of total and unequivocal neutrality should they choose to walk the Middle Path.

The political stuff is pretty basic (and outdated) due to the somewhat constraining timeline of the setting. In this world, there has never been Frankfurt School, Ccru, or Landian NRx. When Kurvitz and Co don’t use political themes to further define Disco Elysium’s wonderful cast of characters, they seem to be perfectly content with poking fun at the shortcomings and disappointments of modernist sensibilities. Yeah, yeah, the annihilating anti-ontological supercloud of death is approaching, voiding every conceivable political action and turning it into farce. I’m okay with that explanation, but to me it looks like they are just not very interested in that stuff. It’s also understandable since the existentialist approach limits how broadly you can cover the topics that are outside of your characters’ immediate perception. Total war is a good compromise.

Although I must say, our cop’s politically flavoured zaniness is a bit jarring when juxtaposed with, say, René’s straightforward monarchist reaction. There may be an in-universe explanation for this dissimilitude (spoilers!), but that doesn’t really change anything in the text itself.

However, despite all the negative political neutrality, the authors’ sympathies are fairly obvious, if only hinted at. Most of those hints are spoilery. Some: not so much. The tare-collecting mini-game, for instance, unambiguously points at one particular plight that suffocates the working class residents of Martinaise. The district is steeped in agonizing, tare-producing drunks whose impressive output allows the RCM officer to live another day. The coastal ruins sing in unison with the cop’s own revenant past. The failure of the Revolution is a festering wound on Martinaise’s bloated face. It’s not an ideologue’s shallow party sympathy either. It feels like a deep, nostalgic longing for what the Revolution, any revolution ultimately stands for: a hope for a future. This sympathy may seem blood red at first, but really, its shade is a tad more… pale.

Antiviral

I don’t think that Disco Elysium is the greatest game of them all or something like that. To think that, one would need to place it in the old and tired hierarchy of cRPGs. Doing so would be missing the entire point. DE is not the best; it’s unlike the rest: in its form, attitude, inspirations, aesthetic principles. An alien from the art planetoid that has brought a taste of real disco with it. I’d say it’s a didactic tale more than anything else. It shows that video games can be a vessel for more than various shades of entertainment and outsider art: the lesson is liberating as much as it is traumatic. It’s not very clear how to proceed from this point forward, but god knows, the medium needed this wake-up call.

Let’s stay up a while.

Fear and Trembling

When I first came upon a short description of Disco Elysium in 2016, I couldn’t help but feel nostalgic. A lot about it reminded me of my college years: from the ambition to change the world to the whiff of highly metaphysical alcoholism that usually accompanies designs so grand. I pictured: scruffy-haired young men in ill-fitting blazers and their makeup-averse amicas, all of them choking on cigarette smoke in a bohemian cafe slash cheap diner. They’re trying to arrive at a hard conclusion: is Kant shit? What about that pompous blowhard Hegel? And when the conversation becomes a bit too heated for the Monday afternoon, someone exclaims: Sartre is the shittiest of them all! Everybody laughs, nods in agreement, and the discussion is taken in another, seemingly unrelated direction.

Having played through the game, I can say that this first impression was both right and wrong. What the mise-en-scène lacked was a board game or two, a pocketful of D&D campaign notes, maybe a pair of loaded *cursed* dice. The unmistakable quixotic aspirations were there. Lots of them.

Disco Elysium is the anxiety-driven, doubt-ridden, schizopolitan brainchild of an Estonian studio called, a bit arrogantly, ZA/UM. In the video game terms, it resembles an RPG/adventure with an unusually strong emphasis on narrative, character study, and failing at life, spectacularly. Dungeon crawling, epic adventuring, kobold-slaying: all of it is cast aside in favour of the exquisitely penned world-building, characterization, and human interaction. Its ambition is no less than an attempt to break out of the standard Skinner box cRPG structure and probe at what lies beyond that particular pleasure principle. If that sounds imposing, boring, or discouraging, then I’d say it’s a call to arms - this disco groove may prove deeply therapeutic for a soul made coarse by the endless stream of inconsequential power fantasies and colourful yet insipid distractions.

The smallest church in Saint-Saëns

Instead of giving us the usual freedom to become a soon-heroic, god-chosen nobody, Disco Elysium puts the player in the tear-and-alcohol-soaked shoes of a particular *somebody*. That somebody has a name, a face (sort of), a semblance of life, and a long history of destructive self-abuse, all of which slowly resurface during the course of the game.

While it may seem somewhat restrictive to disallow self-insertion in a cRPG, it helps the story to focus on the inner turmoil of our character as much as on the people and events that surround him. After all, the game’s original title used to be No Truce With The Furies, and that alone illustrates pretty well how important it must have been for the authors to have a singular ruined soul at the epicenter of the narrative. Since one obviously cannot construct effective personal drama for all possible player avatars (the only guaranteed common trait being player agency), the authors made the furies torment our hero through his prior life. It’s one of the instances where Disco Elysium’s PC-centric pen-and-paper origins shine through and affect the standard cRPG conventions. The scope is narrower but more focused, intimate, intense. A bit like that other text-heavy RPG with a set protagonist.

To dial it back a little and return us to the dimension of *computer* role-playing games and their freedom to play as whomever thou wilt, ZA/UM employs an obscure literary trope known as “total retrograde amnesia.” Or was it a selective memory wipe? A mere pretense fueled by shame? Repressed memories? Something more supra-natural? The reason for blanking out is up to the player to establish later down the line. Whatever the cause, only our past is set in stone, and it is for us to decide what kind of person we will become by the time all hell inevitably breaks loose.

The first step on the path of self-discovery is to distribute 8 points between the four main attributes: intelligence, psyche, physique, and motorics. Each attribute governs 6 thematically appropriate skills that may range from something as simple as Logic or Endurance to the more esoteric Inland Empire and Shivers. I highly recommend everyone to read their full descriptions, even if you don’t plan on investing in some of the skills. Besides providing clues and tips on what attributes to pick for certain archetypes, they’re simply a joy to read.

What really stands out when you start familiarizing yourself with the skills is how difficult it may be to fit some of them into the existing RPG categories. It takes a bit of time with the game to truly get what Esprit de Corps is really about, for example. What do Shivers actually do? What’s the difference between Drama and Suggestion? The skill selection might be the player’s first encounter with the experimental side of Disco Elysium, a sign of things to come. It only gets weirder - and sadder.

After a binge of world-ending proportions, our nameless, featureless, and pantsless hero wakes up on the floor, in a room, in a city, on a continent; all of them totally unknown and mysterious (except maybe the floor). How does one proceed under such arcane circumstances? By initiating an inner monologue of course! But who does the talking? Your skills, my liege. Depending on your choices during character creation, it may be Inland Empire lamenting that we didn’t get to see what was on the other side of the killer debauch, or Logic trying to piece something together from what little information about our current situation we have, or Pain Threshold welcoming the anguish that comes with being alive. They start talking when you regain some of your higher cognitive faculties and don’t shut up until the credits roll.

The easiest way to understand how you interact with your skills is to imagine the bicameral mind and-- that’s it, actually. That is exactly how it’s done. The player is in control of what the cop (ah, that’s one mystery solved) says and does, and your skills do most of the background thinking, guiding you to failure and regret (and an occasional triumph).

Oddly enough, each of them has a distinct personality and a... portrait. In a lesser RPG, these could have been templates for the player’s potential party members. They’re chatty, opinionated, and, most importantly, often fallible. Half Light, the mix of a psychotic barbarian and a scaredy-cat which is supposed to represent your fight-or-flight response and vigilance in the face of danger, will misjudge the gravity of a situation as often as assess one correctly. Despite its strong-willed facade, Authority often acts as a feeble sleazeball that tries to exploit its position in the warrior caste and use it as a lever to subjugate other people and get RESPECT. Conceptualization is just a third year humanities student always looking for opportunities to turn life into a living canvas. Fair enough. 24 almost-people to see you through this week-long hangover.

Not all skills are created equal, though, and some of them lack a particular “bang,” be it their practical application or even the number of times they’re used. Savoir Faire and Pain Threshold rarely if ever pop up. A couple of others mostly just produce flavour text (which is barely criticism in Disco’s case). The skills, however, are grouped in such a way that every attribute has bread-and-butter and novelty skills alike, so you don’t need to worry: if you heavily specialize in an attribute, you’ll always have friends like Rhetoric or Suggestion to steer you to excellence.

My personal uncontested favourite is Inland Empire. Aptly named after a David Lynch film, it’s a skill that’s for the most part concerned with the otherness of everyday phenomena, Jungian shadow, and ontological rifts in reality. It has an appetite for everything mysterious, unexplained, weird, and hidden from the uninitiated. Inland Empire always chimes in when a door, a threshold, or a transitory state comes up; it’s the part of your psyche that wonders what’s hidden on the dark side of the Moon. The writers themselves are obviously in love with both the skill and what it stands for as Inland Empire directly engages with some of the central themes and events of the story in a particularly meaningful way. If you’re dead set on finally catching up with the everfleeting Miracle, you probably should pick Inland Empire as your signature skill, giving it the little crown it deserves.

Unlike a myriad of hidden (and static) skill checks that provide information and insight, obstacles and conflicts in Disco Elysium are usually resolved with a dice roll. To determine whether you conquer a challenge or not, an invisible game master rolls 2d6, adds your skill value to the result, and compares it against the difficulty rating. Some of them are one-time opportunities while others can be retried at a later point in the game. The challenges themselves range in scale and daring: from raising your hand to pick up an article of clothing to actively unveiling humanity-defining existential mysteries. It’s not necessary to pass them all to get to the end, so you probably shouldn’t feel bad about failing some. Besides, your failures more often than not bring about such spectacular, grotesque, or simply funny results that you can’t help but roll with them.

Another curious part of the character-building system is the Thought Cabinet. While you explore the oneiric gameworld and interact with its aborigines, a thought (or ten) may be born of your actions, words, attitudes. In a curious display of self-awareness, the cop puts the fruit of his experiences in a mental trunk where it’s kept in relative safety until he’s finally ready to internalise it. Naturally, coming to terms with a mode of thinking and *really* making it your own takes time and effort. The rigidity of this process subjects us to various thematically appropriate maluses: incoherent ramblings are a known side-effect of becoming the harbinger of end times. But even when it’s done, and there is no escaping Revacholian Nationhood squatting inside your brain-box 24/7, the adverse effects of *thinking* will not let go; they’ll merely mutate. On the bright side, there’s always something positive about being eaten alive by your own thought process, so every bit of wisdom yields a reward of some sort upon its internalisation (be it XP rewards for your spontaneous bouts of creativity, the heightened effects of a drug, or simple skill bonuses).

Much like the skills, thoughts are beautifully illustrated, except the portraits give way to more complex surrealist vignettes. Interestingly enough, the vignettes are not separate drawings: each of them is the part of a gigantic, intricate, and surprisingly visionary mural of intertwining chimeras.

Infinite Comedy

“During these three days, I must have been alert, conscious and self-aware, feeling the continuity of memory, sure of my identity and existence. An event that followed them, though, eradicated them, just as one day death would erase all memory. It was my first experience of a kind of death and, since then, although unconsciousness itself was not to be feared, I saw memory as the key to sentience. I existed as long as I remembered.”

Christopher Priest, The Affirmation

Christopher Priest, The Affirmation

Unresolved police business. Property damage. The suspicious demeanor of a disco woman. A stuffed bird, posthumously injured in a drunken stupor. Problems rapidly pile up once we step out of our hotel room. The cafeteria manager is angry with us: we trashed his joint the night before, and apparently there’s a dead man hanging from a noose out back, stinking up the place. He points to the exit. A man in an orange bomber jacket, hands behind his back, is casting expectant glances in our direction. Maybe he knows who - or what - we are? Noticing bottles of spirits lining the shelves, Electrochemistry, our inner sex and drugs connoisseur, sings odes to narcotic substances and urges us to have some. Cut it out, it’s not the right time. Or is it?

The bomber turns out to be our new partner, Kim Kitsuragi, a mild-mannered, reserved, secretly stoic, and somewhat anal officer of the Revachol Citizen’s Militia, or the RCM for short. We, however crazy that may sound, are an RCM officer as well, albeit from a different precinct. Some days ago a security guard was lynched in Martinaise, and we were sent by the station to investigate - four days after the fact. Locals say he has been hanging from a tree for a week. But wait a second, what is Revachol? Martinaise? People keep mentioning these places like they are supposed to ring a bell. And shouldn’t a cop have a badge?

The amnesia angle of the story is framed so vividly it’s intoxicating. It’s impossible not to feel the cop’s sheer vertigo and confusion when he’s confronting the unknown, a world that seems more an etheric plane than a tangible place. Luckily for us, Kim and an ensemble of supporting characters are patient enough to guide us through the initial shock and give us a couple of pointers along the way. With a thorough reality low-down hours away, we don’t have a choice but to cope and do our job. Outside the hotel, streaks of cold rain anoint our swollen face. A sorrowful instrumental song begins playing; a tune so foreboding and melancholic it’d give Godspeed You! Black Emperor a run for their money. Standing in the rain, the cop takes a deep breath and lets Shivers take hold. His vision crystallizes. Martinaise is the ailing harbour district of the city of Revachol. It’s been 50 years since the Revolution failed, and a foreign offensive left the district in both ruins and economic servitude. Buildings are crumbling, shell craters and bullet holes riddle the waterfront. The other side of the river is dotted with rustic fisherman’s shacks. 6000 kilometers to the north, the world is ending. The Pale is encroaching on the oecumene.

As strange as it may sound, Elysium is a game about hauntings. The deserted streets of Martinaise and its collapsing houses are sparsely populated by odd, out-of-time characters, whose presence almost intrudes on this apocalyptic timescape. René, a former royalist soldier, spends his days in the shadow of the Revolution and its folly; he’s fully uniformed, grumpy, and completely unable to leave his past behind. Then there’s Lena, the life partner of a certain cryptozoologist, who still believes in and chases after a miracle she encountered decades ago. Or a vanished university student whose abandoned apartment sits unnoticed in a dusty hallway. The traces of his obsession with the life, ideas, and suicide of Kras Mazov, the father of Communism, are all that’s left of him. An empty flat haunted by the print of a young man obsessed with the ghost of a theoretician killed by a dream. A hauntological matryoshka doll of apparitions! Not to mention an entire commercial area that is apparently besieged by the spirits from a bygone era, some of whom still roam its intercom lines. It is in our cop’s heart, however, where the rattle of spectral chains is the loudest. The disco writers’ preoccupation with the past lingering in the present is truly fascinating. Any possible future seems thoroughly cancelled. The past stays unresolved indefinitely. 28 years until the final and decisive end of history.

But of course, it’s only one side of the 1 reál coin. It wouldn’t be possible to survive the wasteland if not for Dionysus’ wine. Disco is all about empathy, connection (as shallow and fragile as it may be), and anodic dance vibes. A feast in time of death is a feast nonetheless. Don’t get me wrong, in Disco, there’s plenty of life, laughter, and the inebriation they bring. The characters stave off The Pale as best they can, and it’s a heartwarming performance indeed. The ghosts, though… there’s too many of them. They are more prominent, they wail louder and chill you deeper. Their ghoulish touch is what you’ll feel long after the curtains have been drawn.

Arguably, Disco Elysium’s greatest achievement is how almost uncannily organic the way in which the subtext is woven into the narrative is. Its ability to paint on both literal and allegorical levels simultaneously deserves a warm applause. Sure, it misfires a couple of times, but that barely detracts from the finesse on display. A comparison with Latin American magical realism would be quite trite, but that’s what it feels like for the most part. Symbolic meaning can be casually and mostly effortlessly assigned to the different parts of the text. The end result is a nifty and tight second layer of meaning that complements the main textual stratum. Although it’s worth noting that it might not always be optional. I can see how some players may feel unsatisfied with the story’s resolution if they don’t engage in a bit of critical reading at the end. But again, the fantastic elements are contextualised well enough to make sense even when taken at face value.

It’s tempting to characterize Disco as a metamodernist game. In the main bulk of its writing, it manages to almost entirely avoid irony and postmodern distance in favor of earnestness and openness. The text is rarely if ever bastardised by the shopworn collage and intertextual techniques. But it’s not entirely naive either: it’s fully conscious of the historical context in which it was created, and yet it isn’t held back by the knowledge. The authors aren’t afraid to coin a plethora of unusual composite words (Zaum, but not really), to meaningfully employ music and art to enhance the impact of their litterae, to push the envelope until they bleed and their hearts give out. Wisely, the grotesque pomo abominations are kept in a pen and only let out to serve the goals of New Sincerity. A metafictional subplot is a curious divergence from the ethos, not the norm. Of the new and old, the former reigns supreme.

It’d be less painful to let go: she has long turned her back on you. But who could muster the courage to do so?

Seize the means of representation

Existentialism as a creative modus is inherently politically neutral, and Disco’s writers don’t seem to have qualms with the fact (at least on the surface). Political themes mainly serve as a backdrop, and the player’s four possible political affiliations-communism, fascism, ultraliberalism (wheeze), moralism-are played for laughs. Consciously avoiding the unsavory label of agitprop (surely, ideologically supercharged RPGs should be classified as torture devices), ZA/UM often presents the entire spectrum in an exaggerated, even comical manner. Prepare for your inner communist to be a walking cliché that ceaselessly rants about the plight of the working class, the fangs on those capitalist superpredators, and the inevitable redistribution of their wealth. From the half-opposite side of the political compass you’ll hear the fascist’s colourful tirades about immigrants ruining everything and the onset of a plague of civilization-destroying degeneracy. Only radical centrists are going to enjoy the lulling peace of total and unequivocal neutrality should they choose to walk the Middle Path.

The political stuff is pretty basic (and outdated) due to the somewhat constraining timeline of the setting. In this world, there has never been Frankfurt School, Ccru, or Landian NRx. When Kurvitz and Co don’t use political themes to further define Disco Elysium’s wonderful cast of characters, they seem to be perfectly content with poking fun at the shortcomings and disappointments of modernist sensibilities. Yeah, yeah, the annihilating anti-ontological supercloud of death is approaching, voiding every conceivable political action and turning it into farce. I’m okay with that explanation, but to me it looks like they are just not very interested in that stuff. It’s also understandable since the existentialist approach limits how broadly you can cover the topics that are outside of your characters’ immediate perception. Total war is a good compromise.

Although I must say, our cop’s politically flavoured zaniness is a bit jarring when juxtaposed with, say, René’s straightforward monarchist reaction. There may be an in-universe explanation for this dissimilitude (spoilers!), but that doesn’t really change anything in the text itself.

However, despite all the negative political neutrality, the authors’ sympathies are fairly obvious, if only hinted at. Most of those hints are spoilery. Some: not so much. The tare-collecting mini-game, for instance, unambiguously points at one particular plight that suffocates the working class residents of Martinaise. The district is steeped in agonizing, tare-producing drunks whose impressive output allows the RCM officer to live another day. The coastal ruins sing in unison with the cop’s own revenant past. The failure of the Revolution is a festering wound on Martinaise’s bloated face. It’s not an ideologue’s shallow party sympathy either. It feels like a deep, nostalgic longing for what the Revolution, any revolution ultimately stands for: a hope for a future. This sympathy may seem blood red at first, but really, its shade is a tad more… pale.

Antiviral

I don’t think that Disco Elysium is the greatest game of them all or something like that. To think that, one would need to place it in the old and tired hierarchy of cRPGs. Doing so would be missing the entire point. DE is not the best; it’s unlike the rest: in its form, attitude, inspirations, aesthetic principles. An alien from the art planetoid that has brought a taste of real disco with it. I’d say it’s a didactic tale more than anything else. It shows that video games can be a vessel for more than various shades of entertainment and outsider art: the lesson is liberating as much as it is traumatic. It’s not very clear how to proceed from this point forward, but god knows, the medium needed this wake-up call.

Let’s stay up a while.