RPG Codex Review: Monte Cook's Numenera

RPG Codex Review: Monte Cook's Numenera

Review - posted by Grunker on Sun 19 January 2014, 23:30:51

Tags: Monte Cook; Numenera; Torment: Tides of NumeneraWritten and edited by Alex

Minor edits by Grunker

Numenera is a table top role playing game, released last year by Monte Cook, who has a long credentials list, but should probably be most well known around here for his work in several of the AD&D 2nd Edition Planescape supplements, as well as being one of the designers of D&D 3rd edition. Numenera began as a Kickstarter, and managed to do very well, totaling $517,255 (from a goal of only $20,000). The main rule book was released in August, together with the Numenera Player's Guide. Already, supplements and an adventure are planned for the setting, as well as a brand new game with its own Kickstarter, The Strange. But perhaps more important for the Codex, Numenera is also planned to be the setting for the upcoming game, Torment: Tides of Numenera, which also promises to be a spiritual successor for local favorite Planescape: Torment. A book called Numenera Player's Guide was also released, but its contents are actually just the first chapters from the Numenera book, covering character creation and basic dice rolling rules.

I have tried to review the game as fairly as I could. Still, there are many ways to play RPGs, and while there isn't really a right way to do it, people will still have biases and preferences. In particular, a lot of advice, wording, and rules in Numenera make the game seem pretty clearly geared for "episodic" play, as opposed to "sandbox" play. I won't go into the exact differences here, as there is a whole host of play-styles that can fit under each word, but the basic idea is that sandbox games play more like a wargame campaign, with a greater focus on how things are done, while episodic games play more like a fiction story, with a greater focus on what is done.

Now, I am much more of a sandbox guy myself. Rather than trying to simply ignore my own preferences, however, I have tried to make them clear in my comments. Feel free to ignore these if the mentioned viewpoint doesn't matter for you, though! Furthermore, I am not at all implying that Numenera is awful for sandboxes. In fact, I think it could work great with just a few choice modifications.

For the purpose of this review, I have played this game with a few fellow Codexers (Excidium, Darth Roxor, Jaedar, herostratus, Reject_666_6 and Mystary!). We had only two sessions of play, playing the first introductory adventure that came with the book. I admit this is far from ideal, but I believe even this short play time, coupled with my reading of the book should be enough to make true (if not very deep) criticism of the game.

Numenera is a thick core book, over 400 pages long. Inside is a description of the system and setting of game, as well as gaming materials such as monsters, NPCs and even some sample adventures. The book also has a section on Game Mastering and three appendices.

System-wise, the game is rather simple. Mr. Cook has apparently drawn from the "indie" game scene. I say "indie", because the RPG market already is very independent, and there are independent authors for pretty much any kind of RPG nowadays. But when I say "indie", I mean games done in the spirit of RPG Forge and Story Games. At any rate, Numenera uses mechanics and game elements similar to those in games such as The Shadow of Yesterday, Fate and Apocalypse World (though I suppose Mr. Cook may have found them somewhere else).

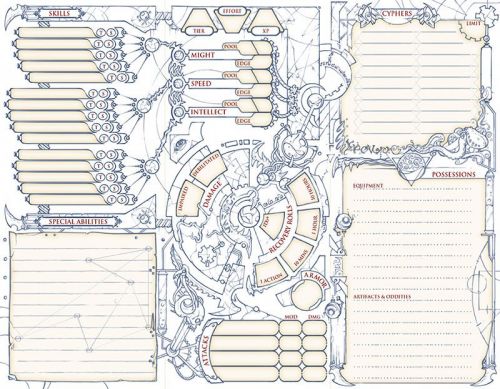

The game has a unified resolution system (the way you determine success or failure of actions). Whenever a PC attempts an action, the GM will define difficulty, between 0 and 10. The player then roll a 20 sided dice, trying to score a number greater than three times the difficulty of the action. Thus, if an action has difficulty 5, you need to roll 15 or more on a D20 to attempt it. At first, this would mean actions with a difficulty of 7 or more are impossible, but it is also possible to reduce the difficulty through various means: namely assets, skills and effort. I will go over these more thoroughly later, but effort is specially important here. Monte wanted to make a game where the players decided how much effort they would put in each action. So, in Numenera, player characters don't have static attribute scores, like in D&D, but attribute pools. They can choose to spend the points in these pools to change the difficulty of actions. For instance, if hitting an enemy with your spear would be difficulty 4, you could choose to spend a few points of your might pool to reduce it to 3 (or even further down to 2 or 1 or 0, making the action an assured success).

Another unusual aspect of the system is that only players roll the dice. For instance, if a PC tries attacking a monster, the player will roll the dice to see if he is able to hit. But if the monster retaliates, the player again rolls the dice, to see if he manages to avoid the attack. The GM doesn't ever need to touch the dice in this game. NPCs' most important characteristic is their "level" value, that determines how competent they are all around. The level is the difficulty PCs will face when trying opposed actions against them. Thus, a level 5 monster needs a difficulty 5 test in order to be hit, to be avoided, to be fooled, etc. Of course, since this would be very dull taken straight, monsters usually have strengths and weaknesses. A thief NPC might be level 3, but act as if he was level 5 when trying to sneak or play dirty tricks on the PCs.

On the setting side, Monte wanted to create what looked like a medieval fantasy setting on first inspection, but turned out to be science fiction underneath. Thus, at its most familiar, Numenera seems somewhat similar to the middle ages Europe, though a version of it with a flair for the fantastic. Behind what most people take to be simply magic, however, lies ancient technology from previous civilizations. These artifacts give the game its name: they are the numenera.

The setting is actually supposedly our own Earth, though around a billion years in the future. In this long span of time, at least eight important civilizations rose and fell. They accomplished much: traveled to the stars, discovered other dimensions, moved the Earth so it wouldn't be destroyed by the expanding Sun and many other feats. At least a few, if not most of these, weren't humans, who supposedly became extinct long ago. Yet a new human civilization, just in its beginnings, has arisen. And they find themselves in a world full of wonders left behind by the previous people who lived there.

Although Numenera is a science fiction setting, the people in there are very medieval. They don't understand the super-science left behind by previous civilizations, and cloth them in superstition and myth. Thus, the world frequently wears a mask of medieval fantasy. The Steadfast, the least strange of the areas, even looks like a bunch of medieval European kingdoms, and look not that different from usual fantasy fare.

One of the most important aspects of the setting is the weird. This the the aesthetic of strange, dangerous and wonderful elements of super-science strewn around the setting and even the Steadfast can be pretty fantastic under its normalcy mask. Take the Iron Wind, a cloud of nanobots that reassembles all matter they find in their way, for instance. It is a dreaded climate condition that can leave people mutated and most likely dead, and even inert matter is changed by it. Because of the extreme technology of the ancient civilizations, no normal materials are considered really rare. Gold, for instance, is as plentiful as silver, iron or copper. Mutants, aliens and creatures from other dimensions can be found anywhere, though they are more common in the Beyond, the lands east of the Steadfast.

Since the Kickstarter, Numenera touted that its character creation system would revolve around describing characters in a single phrase of the type “I am an adjective noun who verbs”. What this actually means, is that when you create a character, you get to choose three aspects of him: type (the noun), descriptor (the adjective) and his focus (the verb). I believe this "adjective noun who verbs" aspect may have been meant as a way for Mr. Cook to convey how Numenera isn't focused at all in "power building", that is, trying to fine tune your character options to make the most powerful character possible. In fact, character creation mostly consists of selecting the three aspects in order. Still, some thought that this implied a more open and "ad hoc" system than it really is. Types, descriptors and foci are all detailed in the rules as sets of very mechanical advantages and sometimes disadvantages. That said, it is easy enough to create new ones, especially foci and descriptors.

There are three types of characters: nanos, who fill a niche similar to wizards in D&D, using "esoteries", which work more or less like spells; glaives, which are very much like warriors, able to use special "fighting moves", which are either special attack modes or specializations in some kind of fighting; and jacks, characters that focus on skills, and are able to learn a few fighting moves and esoteries too. Having only three types may seem too limiting, but it is important to note that the type is more like a general outline of the character. Think of the type as a class, if you will, while the descriptor is a sub-class, or prestige class.

The special abilities of each type is, in my opinion, one of the game's weak points. They are mostly rather limited, there are few of them, and you only get a very limited number of them. Each character starts with two special abilities, and may learn another one at each tier (the game's level equivalent, but there are only 6 tiers). It is possible to sacrifice other tier advancements for extra special abilities, but they still pale somewhat when compared with the powers of numenera or even foci. I don't mean to say they are underpowered, but they aren't as interesting or focused. On one hand, I can see this being the case because Monte didn't want them competing with either. The focus of the system are the numenera, and foci are supposed to be unique and interesting. Still, I think a much better idea would have been to make abilities that actually interact with the numenera.

I also am a bit annoyed that each time you get to a new tier, it is possible to change one of your selected abilities for another of the same or lower level. In other words, "respecing". Of course, it is easy enough to simply ignore this rule in your own game, but it is still a bit sad seeing MMO concepts like this creeping into pen and paper RPGs. To be fair, though, respecing can make sense for some characters, as their abilities can come from, for instance, installed biomechanical devices in their bodies. But in that case, why wouldn't they be able to change those whenever they want?

Speaking of biomechanical devices, each type also has a table with 20 possible "connections": ways in which you came into your abilities, and 3 backgrounds: explanations of why your character has special powers (stuff like being an engineered soldier, mutations causing psychic activity, etc). This is, in my opinion, the best part of the types. They help the GM and the players come up with ways for the players to represent and justify spending XP, as well as creating a connection between the world and the PC.

Moving on to descriptors, these are probably the least important aspect of character creation. Most descriptors give some attribute bonuses, and some skills. But a few have different aspects, such as disabilities (basically an inverse skill, an area where your character performs worse than normal), extra equipment or even less tangible benefits, such as a contact. I don't mean this as a criticism, though. Even if they don't matter that much, they can work well to define your character.

One issue with descriptors are the links. Each descriptor provides a few "links" for the initial adventure. That is, a small explanation of how your character got involved with the rest of the party. These can, of course, be ignored easily enough, especially if the party has decided on a common background or something. But the issue is that the provided links are all rather dry and mundane. I think Mr. Cook may have wanted to provide links that wouldn't get in the way of how you roleplay your PC, or maybe it is just that descriptors are so generic it is hard to base cool links on them. However, I think making them more like adventure seeds and hooks would have been a better idea.

The focus (plural foci) is probably the most interesting aspect of character creation. Your focus is a unique aspect of your character. In fact, no two PCs should have the same foci, and while NPCs might have similar abilities, the foci of a character still should be in some way unique. Foci are the verb of the "adjective noun who verbs". So, they are all in the form of an action, such as "Howls at the Moon", "Masters Defense", "Exists Partially out of Phase", etc. As these names indicate, some of the foci are rather more exotic than others. Still, they are all an important part of character identity. Thus each foci has a particular set of abilities it grants (usually one for each tier, though some grant two on one tier or another), all thematically linked. The "Commands Mental Powers" focus, for instance, begins by providing the ability to talk telepathically, and goes on allowing mental attacks, delving into the minds of others, taking mental control of enemies and even creating telepathic nets with several distant people being able to communicate together (if this seems like a disappointing final power, consider what a smart group of PCs, with a whole army and several competent generals can do with that).

While types had a bit of customization capacity by allowing players to choose a new power each tier, foci are more like a closed deal. This isn't a bad thing, I think, as the game really isn't about power building. There are, however, optional rules for changing and customizing the foci. The rule basically presents a list of possible substitutions for your power in a certain tier. While this may be welcome to people who liked a little more freedom in making their character, the available substitutions are always the same, no matter the focus. So, customization may actually backfire by making the focus less interesting and, well, focused. I think a better idea here would be just to ok with the GM custom changes or even a custom focus for your character. Some foci only really come into their own at later tiers as well, but this isn't that much of an issue.

At any rate, foci have more interesting aspects than just powers. All foci have suggestions for minor and major effects (the Numenera name for critical successes) and for GM intrusions (which is stuff that can happen in fumbles or when the GM "intrudes" in the story, more on that down below, in the rules section). Some of these have a lot of potential! For instance, the "Howls at the Moon" focus, which basically mean you are some kind of shapechanger or lycanthrope, has as a suggestion for his critical, the spread of his condition to the hit creature.

Many foci also provide extra starting equipment. Some of those are obvious like the "Masters Defense" focus, starting a shield. Others are more thematic or interesting, like the "Masters Mental Powers", which begins with a gem that increases his intellect attribute by 1 when worn on his forehead, but which will reduce it by 5 instead if it is lost or stolen. Another interesting aspect is that some foci interact with esoteries. For instance, "Bears a Halo of Fire" makes it so that any esoteries you use that have an energetic component use fire as their energy type. The onslaught spell, for example, might manifest itself as a burning explosion, or maybe a circle of fire.

On the downside of foci, connections, like links, are mostly too obvious even if not mundane. Connections are a "story" aspect of foci, that is, they are about defining the game world instead of defining rules. When you choose your focus, you must choose a PC with whom your powers work differently. The connection of someone who "Crafts Illusions" for instance, is immune to his deceit. In fact, the most common type of connection is someone who is immune to the powers of the focus. Now, again, this stuff being bland isn't so bad. But it feels a bit like a lost opportunity. The idea behind connections seems to be similar to the "HX" mechanic in Apocalypse World. There, each PC started with 1 to 3 connections with others. In AW, these connections were the initial point of the ongoing relationship between the PCs, which had an important mechanical aspect. In Numenera, connections are simply a way to add some spice to the initial party, it seems.

Another aspect I think could have used some work is the openness of the abilities each focus has. Some foci have rather open ones, like "Crafts Illusions" or "Crafts Unique Objects". An illusionist may craft pretty much any kind of illusion he can think up (even more so at later tiers). "Bears a Halo of Fire", on the other hand, has a series of very specific abilities, such as hurling flames or creating a hand made of fire. This isn't nearly as problematic as it might seem, however, if one uses the optional rule where PCs can try to modify the parameters of their powers with a roll. The halo bearer could, with this rule in place, change his fiery hand of doom into a burning foot of kicking by passing a difficulty 4 test. I just think it would have been better if all abilities were written with a more open approach in mind from the get go, though. For instance, instead of having a fiery hand, the halo bearer could have the ability to move, solidify and shape his fiery halo with his mind. Thus, each individual application would flow from that. Of course, less generic, but quirky, and interesting abilities are always welcome, but some focus don't have any open abilities.

All this said, foci are still the most interesting and flavorful aspect of character creation. I think one way to make them more interesting in your game is the same idea I will later on voice about numenera: make them more like a mystery. The book's approach to foci is still, at the end of the day, very rules based, and it is up to the GM to make something more interesting and connected to the setting out of them.

As I mentioned earlier, Numenera uses a unified resolution system. This is tightly linked with the game's attributes; every time the players roll the dice, the GM needs to define what ability governs the action: Might, Speed or Intellect (the game has only 3 attributes). If the player decides to spend "effort", that is the poll that must fuel it. Besides the pool, each attribute also has an edge value. The edge is subtracted from any expenditure made. For instance, putting two levels of effort in an action usually costs 5 points (it is always 3 points for the first level of effort and 2 for the subsequent ones), but with an edge of 2, it would cost only 3. In particular, having an edge of 3 in an attribute means one free level of effort, or any related actions being 1 step easier.

All this may be a bit hard to swallow. Attributes here work in a very different manner from traditional RPGs. There isn't really anything here saying how strong your character is, for instance. A low tier character with 20 points of might will find a difficulty 8 task impossible without some other kind of facilitator (maybe a lever or someone's help). A character with might 10, however, but in the 4th tier, could potentially succeed even in a difficulty 10 task, even though he would be exhausted afterwards. This is because the amount of effort one can make depends on his tier.

Attributes then aren't really meant as a measure of the fictional capacity of the character (in fact, NPCs don't have attributes as such). Rather, they are merely an abstract resource, a way to make the player's decisions matter. This kind of approach isn't uncommon in "indie" games, like The Shadow of Yesterday. Depending on your approach to RPGs, this system may be a deal breaker, though I think it is very appropriate to episodic games. I think the biggest issue it might cause comes in sandbox games. I say this because sandbox games usually require the PCs to keep making inferences and guesses from their situation, and having the PCs and NPCs work so differently in a game like this feels a bit like cheating.

Besides effort, die rolls can be modified by two other aspects: assets and skills. Assets are the situational aspect of the task. A first aid kit, a book relating to the task being done, a friend who is helping you sneak by distracting a guard, all these are assets, and all of them can reduce difficulty. Skills on the other hand, are inherent. Each PC will have a range of different skills he is competent in. Skills come in two levels: trained and specialized, and reduce difficulty by 1 and 2 respectively. One interesting aspect of skills is that the game doesn't really have a list of them. Instead, it is up to the player to create what skills his character knows, and the GM to decide if they are too generic.

Of course, an RPG system isn't only about rolling dice to decide success or failure. While deciding success or failure is an important aspect, deciding what actually happens is equally important. Many games have extensive rules, tables and what not to do that. AD&D had several tables detailing what would happen when some action was taken, such as mixing potions ormeeting a new NPC. Numenera takes the opposite approach, though. It leaves to the GM the task of making different situations interesting using something called GM Intrusions.

Basically, the GM can at any time intrude the flow of the story to determine something has happened (that is, an intrusion). When he does so, however, he gives the most obviously affected character 1 experience point (XP) and another to another character chosen by the first player (this choice can be based on any criteria the player wants). This is not to say the GM needs to pay experience everytime he "GMs". If he had decided before the adventure began that a caravan would arrive on the second morning on the settlement the characters start, he does not have to pay XP for it to happen. Intrusions are instead "nudges" the GM uses to either make the story more interesting or to make it flow some direction he wanted it to. Also, while intrusions override die rolls, they may be negated if the player decides to spend 1 XP point instead of receiving one.

This rule makes the game very "story" based. That is, how the narrative of the game flows is kind of the focus here. What kind of story is, of course, up to the GM. Some will use it to make the gameworld seem more gritty and hostile, some will handwave minor details and use this to make the game seem more "epic", etc. But the nature of the intrusion is exactly that, it is an intrusion, not the normal flow of the game and its rules. In other words, intrusions are very much a way for the GM to be more like an author, instead of, say, a simulator. Also, by the absence of rules that would traditionally take this role, such as random tables, encounter charts and what not, the game loses some communication power. This is much more of an issue in sandbox games, where the definiteness of information may be crucial in helping the players making decisions. On the other hand, both aspects fit perfectly with Numenera's episodic approach and its weird aesthetic. Also, the book has optional guidelines if you want to roll dice instead of making intrusions, though not a whole lot of support for that. I don't mean that the game has rules that get in the way (Numenera was written so it could be changed easily), but that you will need to come up with stuff like random encounters, critical attacks and fumbles and what not by yourself.

As a side note, the intrusions are somewhat similar to how the Fate game system "compels aspects". Different from Numenera, Fate aspects rely on, well, aspects. While a GM intruding in Numenera can choose to do so for whatever reason, in Fate, this must be in accordance to what is known of the situation, not GM's whim. To be fair, the book has a few ideas of how to make intrusions based on the situation. Foci for instance have possible intrusions, as do monsters, that the GM might want to use or adapt. I don't really believe any approach is intrinsically superior to the other: however, this showcases two aspects of the game I feel are important, and are in opposition to the "indie" RPGs it draws from. Numenera isn't really collaborative. That is, the rules mostly don't really care about giving the players much chance to define the setting themselves. A group that wants to play like this won't find obstacles, of course, but the rules aren't made with this in mind like, say, Fate or Shadow of Yesterday or even Burning Wheel. Second, Numenera doesn't really incorporate "story" in its rules. While Fate may use pieces of the story in its rules as aspects, Monte's game is mostly neutral to things like this. It is up to the GM to use the rules according to the specific situation in the game world, instead of the other way around. In these aspects, then, Numenera is more conventional than some of the games it drew inspiration from.

The book also has many situation specific rules. Stuff like how to roll initiative, how long it takes to craft or fix numenera , how to deal with environmental damage, etc. The game is somewhat freeform in this, though and some rules require GM arbitration to apply. Mostly, all of the game's rules are pretty light, made for ease of use by the GM, who chooses how to apply them. This is a bit different from how most "indie" games work nowadays. Indie games usually try to craft their rules to invoke some aspect of story making and the theme they are associated with. Numenera on the other hand, gives the GM bits and pieces of systems, to assemble however he wants or prefers. In the end, this is really a difference of philosophy, just another way that Numenera keeps its rules separated from the "story".

As mentioned, intrusions are one way to earn XP. There is another though: discoveries. Numenera is all about discovery, about finding ruins, wonders and mysteries left behind by the previous civilizations. Having the experience points be based on finding, exploring and interacting with those makes perfect sense. Intrusions being the other source of XP may seem a little strange though. At first, I even thought Mr. Cook might have just have used them because he wanted intrusions to be negotiable. But if that was the case, it would be easy enough for intrusions to work on attribute points rather than XP. I think I have come to understand it, though. Intrusions are actually deeply rooted in the episodic nature of the game. They keep the game flowing like a story. The GM is supposed to help the story flow (or else the PCs will lose half of the XP they would otherwise earn) and the players are supposed to go along with it. Which is not to say that PCs have no agency, they can refuse XP points after all. Of course, this kind of gets in the way of a sandbox game, though it isn't impossible to fix either.

XP in Numenera can be used in some different ways, depending on how long ranging their effect will be. A single point of experience can be used to re-roll the die. Two can be used for a minor, short term effect, such as becoming skilled in climbing not any and all mountains, but a specific mountain the PC found. Three points can net you a more long-term effect, such as an ally or something like a very limited skills. Four points is enough to buy the permanent advancements needed to raise a character's tier. Different from the other options, though, these aren't ad hoc at all. Any permanent advancement your character earns need to fall into a basic scheme, where each character gets 4 advancements per tier.

Also, the use of XP for differing kinds of advantages, going from as ephemeral as a dice roll to something like permanent advancement is a bit odd. This can work really well in some games, like the old Marvel Super Heroes RPG. But in a game where advancement isn't the issue, like Numenera, it feels a bit weird. The idea of using XPs either in a tight spot or not is that if you don't use them, you are rewarded with quicker advancement, but that isn't supposed to matter here. That said, this issue is easily fixed with a house rule on how many XPs can be spent on each category.

The way Numenera deals with damage is interesting. Since the attribute pool is supposed to be the major resource the players draw from, both to increase their odds of success as well as for fueling special moves, it makes sense that damage also uses them. Any attack in Numenera will target one of the three attribute pools, depending on its nature. Most physical attacks, for instance, target might, while mental ones target intellect. Once an attribute is depleted, attacks will damage the other pools even if they normally wouldn't, and the PC becomes a little worse for the wear (using something called the damage track). If all 3 are emptied, the PC dies.

Using such an abstract system has a few issues however. The most glaring is that a PC may rest up to four times in a single day, recovering attribute points. This means that damage is usually pretty short lasting in Numenera. A few days will see most PCs brought back to full health even after a bloody battle. Some optional rules aim to fix this by providing the GM with rules for lasting and even permanent injuries, though it is still up to the GM how these are administered. Damage is also another aspect where NPCs are very different from PCs, as they have hit points instead of attribute pools. This means that NPCs don't become worse off by being hit in combat like PCs do.

All in all, while I don't find the basic rules in Numenera very good for what I would like to do with them, I can't really fault them. If you want to use it for a sandbox game, like a hexcrawl or a megadungeon or something like that, you will have a bit of trouble fine tuning stuff so they work well for that. But if you want to do an episodic play thing, where the GM comes up with the basic outline of what will happen every week and throws the players in it, it works very well. Especially if your game is supposed to feel more like a fantasy novel rather than a tactical exercise.

Items in Numenera are of two kinds: normal items and the actual numenera. Numenera are pieces of technology left behind by one of the previous 8 civilizations. For the people of the ninth world (the way Numenera refers to the current era), they look nothing short of magical: in fact, there seems to be little one of these can't accomplish. On the other hand, there are the "normal" items. Most of these are things that people of the current age can make. The tech level of the current civilization is more or less medieval, thus, the normal item list of the game looks more or less like D&D. However, numenera are everywhere. So a few pieces of minor technology are so commonly found around that they are considered normal items as well by the game. Even stuff made in the ninth world isn't quite medieval, as non standard materials are plentiful. A chain armor, for instance, might be made of a transparent glass that is nevertheless harder than steel, for instance.

The normal items chapter gives three kinds of armor: light, medium and heavy. Usually, these provide respectively 1, 2, or 3 points of armor. These armor points are simply subtracted from any damage the character receives. Although the book provides mundane examples of different armor that fall in the same category, they aren't really mechanically different. The GM can make this aspect matter in setting up difficulties or through intrusions.

Similarly, weapons too fall on one of the categories: light, medium or heavy. These cause respectively 2, 4 and 6 points of damage. On that note, damage in this game is always static, not based on dice rolls. Still, weapons have more variety than armors, some weapons have ranged capability (and some are rapid-fire capable). A few others have notes, though with no obvious mechanic effects, but it is relatively easy to add these on the fly. For instance, a hafted weapon with a hook can work as an asset for trying to knock down your enemy, or maybe disarm him. Still, the game could have made a better job to support that. The notes about how some of the more exotic weapons are used are nice, but are a bit short.

The chapter on normal items also gives some interesting bits of fluff, such as different materials used in the ninth world for construction, like organic stones and special metals. Or more mechanically usable things like miscellaneous items, such as books, provisions, light sources, etc. The chapter is actually pretty small, and there aren't so many items in it, but at least it makes an effort to provide interesting stuff. Prices are also defined in "shins". These are generic coins, usually made of metal, accepted in most of the civilized areas. The prices, specially for a sandbox game, don't hold up that well. For instance, a simple meal costs 1 shin, while a great sword costs 5 and plate armor can be obtained for 15. Either meals are extremely expensive in the ninth world, or basic equipment is extremely cheap, which isn't impossible at any rate, but still feels off. For instance, the Stingcharge, a weak numenera that can sometimes be found in bazaars, can be bought when found by 750 shins. Even if the PCs could sell it only for 500, that would be enough to arm with great swords and plate armor 25 people. The game also, different from D&D 3e, doesn't provide any kind of measure of how much NPCs would expect to be paid. I think the issue here is that Mr. Cook's assumption is that we won't play with the mundane, at least for very long. The game is about interacting with numenera, not about making a crafty trap using only ropes, a hook and a horn, or how you explore the gigantic dungeon using a couple of woodworkers, torchbearers, a score of miners and what not. Still, this isn't that difficulty to fix, simply take the prices directly from AD&D, or Aurora's Guide to the Realms or whatever your favorite source is.

On to the numenera, the game divides them in 4 categories. The first are cyphers. These are "single use", fire and forget items. Explosives, poisons, a medicine that can heal any disease, a cutter able to effortlessly slice up almost anything once turned on, but which powers down after 10 minutes, all these are examples of cyphers. While the book has several other examples, and even a table for randomly generating them, the GM is also encouraged to write his own as well. In the guidelines for them, Monte explains that pretty much any effect can be put in a cypher. And while he recommends that not all, or even most cyphers be particularly powerful, the GM should feel free to go wild here. The reason is that not only are cyphers one use items only, but player characters have a limited capacity to carry them. In fact, cyphers are supposed to be like character abilities that change all the time. So, the amount of numenera a character can carry depends on his type and tier.

This limitation rule is probably one of the hardest to swallow in Numenera, and even Monte openly states it is there simply as a "balancing" factor. Perhaps I should rather say it to be a game direction issue, rather than a balancing one. The problem isn't so much that PCs should be somehow equivalent, but that the "spotlight" of the game should focus on the items regularly, more like in a science fiction story. Instead of the more "game like" approach where PCs hoard items in the hopes of accomplishing something apparently impossible with them. That said, people who care for internal consistency may find this a bit ham-fisted. The book tries to soften this problem by providing explanations or giving alternatives: a table of possible disasters that can happen by bringing too many cyphers together is provided, as is an optional rule where each cypher has an expiration date instead of being volatile.

While the game provides some interesting effects for the cyphers, it doesn't give the GM a whole lot to make cyphers interesting as a setting element. All it provides are sample forms they can take. For instance, the Machine Control Implant (a numenera that allows the user to control another device using his mind alone) can be a pill, a disk one sticks to his own forehead, a temporary tattoo or an injector. Of course, wanting each cypher to be really unique would have required a lot more pages in an already big book, but the game could still have paid some more attention to fluff.

The second category, artifacts, are most notable for being usable more than once, though they too are bound to eventually power down. Rather than keeping charges for each artifact, each time one is used, a roll is done to see if it has finally powered down. Some numenera will work only a few times, like those that power down in a 1-4 in a d6, while others might outlast most campaigns (1 in a d100). Some will only power down when the GM decides they do. While this quantic way of keeping track of charges can be exciting, it can get a bit roll-heavy. Uncharged artifacts can (if the GM allows it) be repaired. However, this uses the rules for crafting, which means that rare materials and maybe a whole lot of time may be involved (in the order of years of work for the higher tier artifacts).

There is a good variety to the artifacts provided in the book. A few of them are rather obvious, weapons like disruption blade, armor like the dimensional armor. Others are more strange and unusual, like the chameleon cloak or the hover square (which looks a lot like Tenser's Floating Disk in concept). A few of the artifacts on the other hand are rather more weird, like the ecstasy paralyzer, which not only disables its target for one turn, but also can be used in a rapid fire fashion! Some of the artifacts seem more geared to sandbox play, like the food analyzer, the trigger trap and the automated cook. A few of them manage to be a bit bizarre, like the pods, biological elements that can fuse with humans and give them permanent abilities, or increase their attributes.

The game, of course, also provides guidelines for the creation of artifacts. Different from cyphers, GMs should pay attention to what kind of ability an artifact enables. First, because even the most quick to be spent artifact still will probably yield 2 uses at least. Thus, its ability could render moot not just a single encounter, but a whole adventure. Also, artifacts don't occupy slots like cyphers do (which sounds a bit silly, given that artifacts, by being charged and sometimes more powerful, would be expected to emit even more radiation/chemicals/whatever than cyphers, but nevermind). Thus, PCs may accumulate artifacts over time. Still, the game has some examples of pretty powerful artifacts, and thankfully the game doesn't fret too much over balance.

Artifacts thus are a bit better, fluff wise, in that they are a bit more evocative, in the average, than cyphers. And the book has some ideas of how the GM can further make an artifact unique. Still, Numenera doesn't really provide any guidelines for PCs to actually interact with these items, either cyphers or artifacts, other than simple dice to determine success and failure. Interacting with the strange technology should, I think, involve some measure of "puzzle solving". While the GM is free to do this kind of thing in this game, there isn't anything in the book to really support this.

The other two types of items are oddities and discoveries. Both have in common that the book doesn't really have any hard rules for treating them. They are very different otherwise, however. Oddities are simply a fluff matter. They don't have rules because they aren't usually supposed to do much that would require them. Frequently, the PCs won't even know what the purpose of an oddity they found was, though they might use it to heat their meals or to keep their coffee warm, or it might just be a six fingered glove or something like that.

Discoveries on the other hand, are capable of pretty much anything. A portal connecting to another planet or an automated operating table capable of being used to implant someone with cybernetics. Discoveries can be a pretty big deal (though, sometimes, they may be interesting, but not really useful). The book suggests they are, however, best thought about as part of the adventure. If the PCs do find a portal to another planet, the point is getting them to that other planet. In a sandbox game this assumption would be a bit wrong. The PCs find the portal to another planet will probably exploit it by trading things between both worlds that are rare in one but plentiful in the other. The implantation table will be used in every NPC who is part of the PC's retinue, etc. Still, it isn't like this assumption invalidates present discoveries, as the book leaves it up completely to the GM to come up with them.

Overall, the numenera and items in the book are good and interesting, if a bit on the abstract side. Given how important these are, it would have been nice if there were more of them. Though one of the planned sourcebooks will be all about them. Also, given how important the weird is, some more work could have been done to make the numenera seem more strange and inhuman. Many of them are pretty utilitarian, even if they aren't being used for their original purpose.

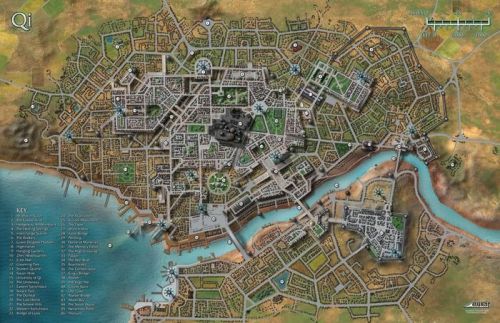

In Numenera, the continents have, somehow, drifted together again. Most of the gigantic landmass formed by their fusion is unexplored, however, and the most well known part is called the Steadfast. This is the most civilized area in the world (well, known world at any rate). It is also the most detailed part of the setting. The Steadfast is a collection of nine kingdoms, seemingly more or less based on medieval Europe. This was, for some backers, a bit of a surprise. Numenera is, by design, an alien setting. A place where any metal or alloy we know of today can be found with equal ease. A place where the weather can suddenly turn for the worse and begin to rebuild you as a completely different organism. But even so, the Steadfast feels familiar. Of course, there is a lot of weird to be found around, secrets and pieces from other eras lying around, just waiting to be explored. But the world still feels familiar, like it could have come straight from The Forgotten Realms or The Greyhawk Setting.

Now, while this might be a let down if you were expecting the game to be completely absorbed in the spirit of the New Sun books (a big source of inspiration for Mr. Cook), having a locus of normalcy does fit a purpose in this game. First, it is pretty hard to play an RPG when everything is alien right off the bat, both for GMs and players. GMs, having to learn how to adjudicate things in the context of the game and players needing to learn what kinds of options they have at any one time. So, having a more easily identifiable area like the Steadfast can help ease the players into the game.

Beyond the Steadfast is, well, "The Beyond". This area, while not devoid of civilization, is more wild, exotic and strange than the lands in the Steadfast. The people in the Beyond are still, mostly, human. But they frequently live in very strange conditions. The city of Vebar, for instance, is formed by ancient buildings that hang along the stalactites of a immense cavern. Bridges and walkways hanging on these stalactites and buildings allow the people to walk around the city, while the distant bottom of the cavern houses the fungal farm that sustains the town. At any rate, the beyond is more nebulous than the Steadfast. While the chapter on it has examples of nations, cities, landmarks and strange artifacts left over in the region, it is still mostly undefined, allowing the GM to build there whatever he wants.

The book even includes a section called "Beyond the Beyond", detailing the Clock of Kara, the northeasternmost area that isn't yet terra incognita. The clock is a gigantic mountain range forming a circle several thousands of kilometers in diameter, with a huge tunnel a little less than 100 miles wide cut through it allowing access to its inside. At the end of this tunnel, called The Sheer, is Wislayn, a strange crystal structure resembling a polyp. People touching it are transported to an extradimensional space that seems to be inside the crystal, which is used as a town by around 1000 people. Besides the clock, the university of doors is shown as an example of extradimensional area the PCs could reach and interact with. Numenera is written so the GM can, if he wants to, easily move the campaign between worlds and dimensions. In fact, I think a previous book by Monte Cook, Beyond Countless Doorways, might work very well with this game though some dimensions in that book might be a bit too fantastic (as in, belonging to fantasy) for Numenera.

I have mentioned the weird a few times now. This is how Mr. Cook refers to the strange, threatening, but also wondrous superscience found in Numenera, as well as its fruits. Sometimes it is lying dormant, or has been doing something useless for eons. Sometimes, it is inimical to humans, and sometimes it is downright inhuman. This is the very heart of the game, whether the weird takes the form of a monster, a machine, a building, a wonderful medicine or whatever else you can think of. This aesthetic is one of the most important aspects of the setting. Not everything strange or alien quite fits it, though.

Take Planescape, for instance. With the new Torment game coming, and since Mr. Cook himself wrote some of the Planescape supplements (though he didn't create the setting itself, that was David "Zeb" Cook, another Cook entirely) I think it is a good comparison. A big draw of the Planescape Campaign Setting back in the day was how different and strange it was (from normal AD&D, at any rate) too. But the ways in which Numenera and Planescape are strange are different. In Planescape, the myth and wonder surround the planes: and at times, the whole setting can become even "fairy tale" like. The logic behind the strangeness in Numenera is very different. In fact, whenever something seems to follow a fantasy logic, it is usually hiding something. Ghosts in Numenera don't haunt because they have unfinished business, but because their memories were uploaded to a machine. Numenera is a science fiction game at its core, and whenever it wears a mask of fantasy, it is actually playing a bit of a farce. Though, as it should be obvious by now, it isn't at all a "hard" science fiction setting (I don't think those even mix with the Dying Earth genre). Still, Mr Cook does try to account for the laws of physics. The world is still round, though it is farther away from the sun. Years still have 365 days, but days are longer, each having 28 hours, etc.

Furthermore, the wonder of the weird is frequently shared by the PCs and many NPCs as well as the players. This is actually in opposition to how Planescape worked. Planescape wasn't medieval, it was, in fact, infinitely cosmopolite (in theory, at least)! All kinds of imaginable creatures met at Sigil to trade and even live together. Creatures that were basically human lived alongside pretty much any inhumanity imaginable. The very politics and services in the city of Sigil were linked to factions that vied not for money but for faith. Even the most weird examples in Numenera, however, have a very human element. That is, the inhuman is almost always the exception. This is important for the right kind of tone, though. To present the inhuman as normal would push the theme of the game more towards either trans-humanism or dystopian fiction, which have a different kind of sense of dread and wonder.

I was quite surprised by how the setting was presented, however. It actually seems to work better in sandbox games rather than episodic ones for once! While there are a lot of adventure seeds spread around the nine countries, there isn't a whole lot of detail on the setting itself. The book doesn't describe any complex web of intrigue or politics ready to snare the PCs. No fixed metaplot to tell the stories of the institutions and countries Mr. Cook created. No NPCs with detailed backstories, just waiting for a group of adventurers to come by so he can enlist them in some fantastic quest. Instead, the maps have details like terrain, rivers, towns, landmarks, fortresses, etc. You will find geopolitical information (even if sometimes superficial), such as what kind of industry sustains a town, how many people live there, etc. NPCs are described in a spartan manner. Many only get a "statblock", which in Numenera's case consists of just a level and situations where his level is increased or decreased. Some are described more in depth, specially if they are powerful in some way, or posses some kind of numenera, but even then, they rarely take more than one or two paragraphs. There is even a list of rumors associated with each area, helping a lot in taking a more sandbox approach to it.

While I personally love this, people wanting a more concrete approach may be disappointed. The setting chapters are full of adventure seeds and ideas of weird things to use in the game, but none of the riddles are given in depth, none are explained. Actually, there are whole plots to be found in the adventures section of the book. While the ready made adventure are actually a bit small, they do a good job of showing how to play the game, and can provide material for a GM in a bind (though you will probably want to customize them a bit first). Still, these plots that are presented don't really hint at converging at something bigger. The approach to the setting throughout is to allow the GM to make it his. A whole lot of stuff is left for the GM to do. Even the previous civilizations that existed on earth, the source of all numenera, aren't really explained, only given a list of things one or some or all of them could do.

The book also mentions several different groups the PCs can interact with. They can even join these if they want, which allows them to exchange a skill they would learn in a tier for a special ability of that group, a move a bit reminiscent of Planescape. The groups are far from as detailed as the factions in that setting. In fact, I had hoped they would have made this friendly to sandbox games as well, with stuff such as how many members each faction has, what kind of forces it controls, etc. Still, this section can help you add flavor to the setting.

One of the groups mentioned, the most important one in fact, actually strikes me as a bit forced. The Order of Truth is a "pseudo" catholic church for the setting's Europe. However, this priesthood doesn't really seem to work as a religion. The priests are really gadgeteers and scientists, trying to figure out how to use the numenera properly. All the mythology and philosophy they feed the people in the services is just flights of fancy around whatever lesson they want to impart. It is hard to imagine that something like this would ever become the most popular religion in the world.

While the organization can obviously have a lot of political power from the accumulated numenera and lore about how to use them, the book doesn't really present any reason why the organization is a religion in first place, when obviously the priests aren't religious themselves. Another example of this is the Truth, Numenera's most spoken language. The truth is supposedly a language based on intellect and rationality. How it remains so when half of the people in the Steadfast can't even read is a big mystery though. By now, obviously, I am nitpicking. After all, silly as thinking people would accept veneration of the intellect as a substitute to religion, it probably isn't all that more silly than think the mythology of the deities in, say, Greyhawk could work as one. I nitpick just because I want to point out that the setting shouldn't be taken as completely "serious". I don't mean it is wacky or anything like that either (though you could easily play it that way too, if you wanted), but just that things here take a backseat to adventure. Which, I think, is at least being true to the source material of Dying Earth fiction, if not particularly to The Book of the New Sun.

Numenera is a well made book. While Mr. Cook can be a bit verbose sometimes, his text does have a good flowing quality to it. He rarely mentions elements that will only be explained much later on (something quite common in RPGs). The book also features several keywords, that is, important words in the text that are bolded, with some explanation or reference on the side bar. So reading the book is quite easy. The book's illustration can vary quite a bit in quality, but at least they still seem like they belong together. Still, if anyone was expecting something as unique as, say, DiTerlizzi's illustrations for Planescape, the book falls short of that.

While the book presents a whole game, it isn't very well suited to newcomers to P&P gaming. I mean, the book does have a GM section in it but it seems more concerned about how Numenera is different from other RPGs, not about how you begin to GM in the first place. A GM who has never played an RPG before will probably have a little trouble at the start, specially since Numenera relies a bit heavily on the GM in its rules.

The GM section of the book is one of its high points, however. The part about what vocabulary to use to create the proper feel for the game is very insightful. In fact, I think that part of the book helped me understand what exactly Monte was shooting for better than any other. It is a pity that section wasn't made longer.

Taken as a whole, Numenera is a bit weird. It isn't quite like some "indie" games: in a way, it is too traditional. On the other hand, it clearly breaks off from, say, D20 traditions by having a system that isn't particularly tactical. It certainly isn't everyone's cup of tea. My playtest group mostly disliked the game, and what seems to have been the biggest deal breaker is how the game is too simple, mechanically. Of course, with a bit of imagination, it is quite possible to make the game more complex, but if you are looking for a game where you will build a character from lots of little options and then use pre-defined actions in combat to conquer your enemies, well, Numenera isn't about that at all. My group also disliked how the system's advancement scheme is rather "flat". While a tier 6 character can do some amazing things a tier 1 would never be able to, they don't have dozens of special abilities. Nor do they first become able to do the impossible, to later become able to do the absurd and finally the ridiculous, like say, in 3e's epic level skill progression. Also, for someone looking for something more "story oriented" like Apocalypse World, or even Burning Wheel, Numenera isn't that kind of game either.

As the basis of a CRPG, Numenera is quite a different beast than, say, D&D 3e. 3e and D20 worked well as the basis of tactical games like Knights of the Chalice and Temple of Elemental Evil. Numenera's combat doesn't have that kind of depth, at least not without a GM. In fact, I think that the ruleset is much more conductive of a kind of "adventurey" CRPG gameplay. Fighting won't be really interesting at all if all the PCs can do is attack, use a special ability or move about. To really reflect the RPG, different fights need different options. But those options shouldn't be given away, like an extra menu option you can just select. The point is that the player should arrive at them, much like the option to blow up the radscorpion cave in Fallout needs the player to examine the cave entrance, instead of being offered as a dialog option somewhere.

Another interesting aspect is how the abstract mechanics would affect the game. Using effort is a very important aspect of the game, but allowing that in a CRPG means that discrete dice rolls must be presented to the player so he can decide what to do. This means, I believe, that Torment designers will approach the game with a rolling centric view. That is, if they are designing an area, they will be thinking about what kind of dice rolls the player can take there, what can affect it (what skills apply, what items can make it easier, etc) and what difficulty the action is. This can be positive, in that it helps them make the area more interactive, but they should also be careful. It is easy to make the whole game about actions and dice rolls, and make the player himself matter little. If there is a puzzle to be solved somewhere, making it a difficulty 7 intellect roll, instead of giving the player an actual puzzle, is a big downer. Actually mixing the player's and character's abilities in making the game is, as always, crucial in making the game fun.

I don't quite see the GM Intrusion system being used in the CRPG, however. If during the game, a window popped up saying something like "You set up camp in the rocks above the desert. However, the fatigue of the journey is too much and you fall asleep (click here to pay 1 XP to not fall asleep)", I think most people wouldn't be able to take it seriously. This kind of thing works in a table-top game because you are always talking with a GM. You are always going in and out of character. In a computer game, even the most abstract one, this kind of thing would be jarring.

Back to Numenera itself, it is a good piece of game design, but one that won't fit well with a lot of people. If you are considering buying it, I would recommend making sure this kind of game would run well with your group. Numenera relies heavily on the GM, and putting the effort in reading the book through is well worth it, even if you only need a small part of it to run a game. The setting and tone can easily be used with other game systems too, though doing so requires work. Not only because you would need to convert some stuff, but also because Numenera's setting isn't really "complete". The GM is supposed to add his own touches by defining a whole lot of things, such as what the previous civilizations were.

Minor edits by Grunker

Numenera Review

Numenera is a table top role playing game, released last year by Monte Cook, who has a long credentials list, but should probably be most well known around here for his work in several of the AD&D 2nd Edition Planescape supplements, as well as being one of the designers of D&D 3rd edition. Numenera began as a Kickstarter, and managed to do very well, totaling $517,255 (from a goal of only $20,000). The main rule book was released in August, together with the Numenera Player's Guide. Already, supplements and an adventure are planned for the setting, as well as a brand new game with its own Kickstarter, The Strange. But perhaps more important for the Codex, Numenera is also planned to be the setting for the upcoming game, Torment: Tides of Numenera, which also promises to be a spiritual successor for local favorite Planescape: Torment. A book called Numenera Player's Guide was also released, but its contents are actually just the first chapters from the Numenera book, covering character creation and basic dice rolling rules.

I have tried to review the game as fairly as I could. Still, there are many ways to play RPGs, and while there isn't really a right way to do it, people will still have biases and preferences. In particular, a lot of advice, wording, and rules in Numenera make the game seem pretty clearly geared for "episodic" play, as opposed to "sandbox" play. I won't go into the exact differences here, as there is a whole host of play-styles that can fit under each word, but the basic idea is that sandbox games play more like a wargame campaign, with a greater focus on how things are done, while episodic games play more like a fiction story, with a greater focus on what is done.

Now, I am much more of a sandbox guy myself. Rather than trying to simply ignore my own preferences, however, I have tried to make them clear in my comments. Feel free to ignore these if the mentioned viewpoint doesn't matter for you, though! Furthermore, I am not at all implying that Numenera is awful for sandboxes. In fact, I think it could work great with just a few choice modifications.

For the purpose of this review, I have played this game with a few fellow Codexers (Excidium, Darth Roxor, Jaedar, herostratus, Reject_666_6 and Mystary!). We had only two sessions of play, playing the first introductory adventure that came with the book. I admit this is far from ideal, but I believe even this short play time, coupled with my reading of the book should be enough to make true (if not very deep) criticism of the game.

Basics

Numenera is a thick core book, over 400 pages long. Inside is a description of the system and setting of game, as well as gaming materials such as monsters, NPCs and even some sample adventures. The book also has a section on Game Mastering and three appendices.

System-wise, the game is rather simple. Mr. Cook has apparently drawn from the "indie" game scene. I say "indie", because the RPG market already is very independent, and there are independent authors for pretty much any kind of RPG nowadays. But when I say "indie", I mean games done in the spirit of RPG Forge and Story Games. At any rate, Numenera uses mechanics and game elements similar to those in games such as The Shadow of Yesterday, Fate and Apocalypse World (though I suppose Mr. Cook may have found them somewhere else).

The game has a unified resolution system (the way you determine success or failure of actions). Whenever a PC attempts an action, the GM will define difficulty, between 0 and 10. The player then roll a 20 sided dice, trying to score a number greater than three times the difficulty of the action. Thus, if an action has difficulty 5, you need to roll 15 or more on a D20 to attempt it. At first, this would mean actions with a difficulty of 7 or more are impossible, but it is also possible to reduce the difficulty through various means: namely assets, skills and effort. I will go over these more thoroughly later, but effort is specially important here. Monte wanted to make a game where the players decided how much effort they would put in each action. So, in Numenera, player characters don't have static attribute scores, like in D&D, but attribute pools. They can choose to spend the points in these pools to change the difficulty of actions. For instance, if hitting an enemy with your spear would be difficulty 4, you could choose to spend a few points of your might pool to reduce it to 3 (or even further down to 2 or 1 or 0, making the action an assured success).

Another unusual aspect of the system is that only players roll the dice. For instance, if a PC tries attacking a monster, the player will roll the dice to see if he is able to hit. But if the monster retaliates, the player again rolls the dice, to see if he manages to avoid the attack. The GM doesn't ever need to touch the dice in this game. NPCs' most important characteristic is their "level" value, that determines how competent they are all around. The level is the difficulty PCs will face when trying opposed actions against them. Thus, a level 5 monster needs a difficulty 5 test in order to be hit, to be avoided, to be fooled, etc. Of course, since this would be very dull taken straight, monsters usually have strengths and weaknesses. A thief NPC might be level 3, but act as if he was level 5 when trying to sneak or play dirty tricks on the PCs.

On the setting side, Monte wanted to create what looked like a medieval fantasy setting on first inspection, but turned out to be science fiction underneath. Thus, at its most familiar, Numenera seems somewhat similar to the middle ages Europe, though a version of it with a flair for the fantastic. Behind what most people take to be simply magic, however, lies ancient technology from previous civilizations. These artifacts give the game its name: they are the numenera.

The setting is actually supposedly our own Earth, though around a billion years in the future. In this long span of time, at least eight important civilizations rose and fell. They accomplished much: traveled to the stars, discovered other dimensions, moved the Earth so it wouldn't be destroyed by the expanding Sun and many other feats. At least a few, if not most of these, weren't humans, who supposedly became extinct long ago. Yet a new human civilization, just in its beginnings, has arisen. And they find themselves in a world full of wonders left behind by the previous people who lived there.

Although Numenera is a science fiction setting, the people in there are very medieval. They don't understand the super-science left behind by previous civilizations, and cloth them in superstition and myth. Thus, the world frequently wears a mask of medieval fantasy. The Steadfast, the least strange of the areas, even looks like a bunch of medieval European kingdoms, and look not that different from usual fantasy fare.

One of the most important aspects of the setting is the weird. This the the aesthetic of strange, dangerous and wonderful elements of super-science strewn around the setting and even the Steadfast can be pretty fantastic under its normalcy mask. Take the Iron Wind, a cloud of nanobots that reassembles all matter they find in their way, for instance. It is a dreaded climate condition that can leave people mutated and most likely dead, and even inert matter is changed by it. Because of the extreme technology of the ancient civilizations, no normal materials are considered really rare. Gold, for instance, is as plentiful as silver, iron or copper. Mutants, aliens and creatures from other dimensions can be found anywhere, though they are more common in the Beyond, the lands east of the Steadfast.

Character Creation

Since the Kickstarter, Numenera touted that its character creation system would revolve around describing characters in a single phrase of the type “I am an adjective noun who verbs”. What this actually means, is that when you create a character, you get to choose three aspects of him: type (the noun), descriptor (the adjective) and his focus (the verb). I believe this "adjective noun who verbs" aspect may have been meant as a way for Mr. Cook to convey how Numenera isn't focused at all in "power building", that is, trying to fine tune your character options to make the most powerful character possible. In fact, character creation mostly consists of selecting the three aspects in order. Still, some thought that this implied a more open and "ad hoc" system than it really is. Types, descriptors and foci are all detailed in the rules as sets of very mechanical advantages and sometimes disadvantages. That said, it is easy enough to create new ones, especially foci and descriptors.

There are three types of characters: nanos, who fill a niche similar to wizards in D&D, using "esoteries", which work more or less like spells; glaives, which are very much like warriors, able to use special "fighting moves", which are either special attack modes or specializations in some kind of fighting; and jacks, characters that focus on skills, and are able to learn a few fighting moves and esoteries too. Having only three types may seem too limiting, but it is important to note that the type is more like a general outline of the character. Think of the type as a class, if you will, while the descriptor is a sub-class, or prestige class.

The special abilities of each type is, in my opinion, one of the game's weak points. They are mostly rather limited, there are few of them, and you only get a very limited number of them. Each character starts with two special abilities, and may learn another one at each tier (the game's level equivalent, but there are only 6 tiers). It is possible to sacrifice other tier advancements for extra special abilities, but they still pale somewhat when compared with the powers of numenera or even foci. I don't mean to say they are underpowered, but they aren't as interesting or focused. On one hand, I can see this being the case because Monte didn't want them competing with either. The focus of the system are the numenera, and foci are supposed to be unique and interesting. Still, I think a much better idea would have been to make abilities that actually interact with the numenera.

I also am a bit annoyed that each time you get to a new tier, it is possible to change one of your selected abilities for another of the same or lower level. In other words, "respecing". Of course, it is easy enough to simply ignore this rule in your own game, but it is still a bit sad seeing MMO concepts like this creeping into pen and paper RPGs. To be fair, though, respecing can make sense for some characters, as their abilities can come from, for instance, installed biomechanical devices in their bodies. But in that case, why wouldn't they be able to change those whenever they want?

Speaking of biomechanical devices, each type also has a table with 20 possible "connections": ways in which you came into your abilities, and 3 backgrounds: explanations of why your character has special powers (stuff like being an engineered soldier, mutations causing psychic activity, etc). This is, in my opinion, the best part of the types. They help the GM and the players come up with ways for the players to represent and justify spending XP, as well as creating a connection between the world and the PC.

Moving on to descriptors, these are probably the least important aspect of character creation. Most descriptors give some attribute bonuses, and some skills. But a few have different aspects, such as disabilities (basically an inverse skill, an area where your character performs worse than normal), extra equipment or even less tangible benefits, such as a contact. I don't mean this as a criticism, though. Even if they don't matter that much, they can work well to define your character.

One issue with descriptors are the links. Each descriptor provides a few "links" for the initial adventure. That is, a small explanation of how your character got involved with the rest of the party. These can, of course, be ignored easily enough, especially if the party has decided on a common background or something. But the issue is that the provided links are all rather dry and mundane. I think Mr. Cook may have wanted to provide links that wouldn't get in the way of how you roleplay your PC, or maybe it is just that descriptors are so generic it is hard to base cool links on them. However, I think making them more like adventure seeds and hooks would have been a better idea.

The focus (plural foci) is probably the most interesting aspect of character creation. Your focus is a unique aspect of your character. In fact, no two PCs should have the same foci, and while NPCs might have similar abilities, the foci of a character still should be in some way unique. Foci are the verb of the "adjective noun who verbs". So, they are all in the form of an action, such as "Howls at the Moon", "Masters Defense", "Exists Partially out of Phase", etc. As these names indicate, some of the foci are rather more exotic than others. Still, they are all an important part of character identity. Thus each foci has a particular set of abilities it grants (usually one for each tier, though some grant two on one tier or another), all thematically linked. The "Commands Mental Powers" focus, for instance, begins by providing the ability to talk telepathically, and goes on allowing mental attacks, delving into the minds of others, taking mental control of enemies and even creating telepathic nets with several distant people being able to communicate together (if this seems like a disappointing final power, consider what a smart group of PCs, with a whole army and several competent generals can do with that).

While types had a bit of customization capacity by allowing players to choose a new power each tier, foci are more like a closed deal. This isn't a bad thing, I think, as the game really isn't about power building. There are, however, optional rules for changing and customizing the foci. The rule basically presents a list of possible substitutions for your power in a certain tier. While this may be welcome to people who liked a little more freedom in making their character, the available substitutions are always the same, no matter the focus. So, customization may actually backfire by making the focus less interesting and, well, focused. I think a better idea here would be just to ok with the GM custom changes or even a custom focus for your character. Some foci only really come into their own at later tiers as well, but this isn't that much of an issue.

At any rate, foci have more interesting aspects than just powers. All foci have suggestions for minor and major effects (the Numenera name for critical successes) and for GM intrusions (which is stuff that can happen in fumbles or when the GM "intrudes" in the story, more on that down below, in the rules section). Some of these have a lot of potential! For instance, the "Howls at the Moon" focus, which basically mean you are some kind of shapechanger or lycanthrope, has as a suggestion for his critical, the spread of his condition to the hit creature.

Many foci also provide extra starting equipment. Some of those are obvious like the "Masters Defense" focus, starting a shield. Others are more thematic or interesting, like the "Masters Mental Powers", which begins with a gem that increases his intellect attribute by 1 when worn on his forehead, but which will reduce it by 5 instead if it is lost or stolen. Another interesting aspect is that some foci interact with esoteries. For instance, "Bears a Halo of Fire" makes it so that any esoteries you use that have an energetic component use fire as their energy type. The onslaught spell, for example, might manifest itself as a burning explosion, or maybe a circle of fire.

On the downside of foci, connections, like links, are mostly too obvious even if not mundane. Connections are a "story" aspect of foci, that is, they are about defining the game world instead of defining rules. When you choose your focus, you must choose a PC with whom your powers work differently. The connection of someone who "Crafts Illusions" for instance, is immune to his deceit. In fact, the most common type of connection is someone who is immune to the powers of the focus. Now, again, this stuff being bland isn't so bad. But it feels a bit like a lost opportunity. The idea behind connections seems to be similar to the "HX" mechanic in Apocalypse World. There, each PC started with 1 to 3 connections with others. In AW, these connections were the initial point of the ongoing relationship between the PCs, which had an important mechanical aspect. In Numenera, connections are simply a way to add some spice to the initial party, it seems.

Another aspect I think could have used some work is the openness of the abilities each focus has. Some foci have rather open ones, like "Crafts Illusions" or "Crafts Unique Objects". An illusionist may craft pretty much any kind of illusion he can think up (even more so at later tiers). "Bears a Halo of Fire", on the other hand, has a series of very specific abilities, such as hurling flames or creating a hand made of fire. This isn't nearly as problematic as it might seem, however, if one uses the optional rule where PCs can try to modify the parameters of their powers with a roll. The halo bearer could, with this rule in place, change his fiery hand of doom into a burning foot of kicking by passing a difficulty 4 test. I just think it would have been better if all abilities were written with a more open approach in mind from the get go, though. For instance, instead of having a fiery hand, the halo bearer could have the ability to move, solidify and shape his fiery halo with his mind. Thus, each individual application would flow from that. Of course, less generic, but quirky, and interesting abilities are always welcome, but some focus don't have any open abilities.

All this said, foci are still the most interesting and flavorful aspect of character creation. I think one way to make them more interesting in your game is the same idea I will later on voice about numenera: make them more like a mystery. The book's approach to foci is still, at the end of the day, very rules based, and it is up to the GM to make something more interesting and connected to the setting out of them.

Rules

As I mentioned earlier, Numenera uses a unified resolution system. This is tightly linked with the game's attributes; every time the players roll the dice, the GM needs to define what ability governs the action: Might, Speed or Intellect (the game has only 3 attributes). If the player decides to spend "effort", that is the poll that must fuel it. Besides the pool, each attribute also has an edge value. The edge is subtracted from any expenditure made. For instance, putting two levels of effort in an action usually costs 5 points (it is always 3 points for the first level of effort and 2 for the subsequent ones), but with an edge of 2, it would cost only 3. In particular, having an edge of 3 in an attribute means one free level of effort, or any related actions being 1 step easier.

All this may be a bit hard to swallow. Attributes here work in a very different manner from traditional RPGs. There isn't really anything here saying how strong your character is, for instance. A low tier character with 20 points of might will find a difficulty 8 task impossible without some other kind of facilitator (maybe a lever or someone's help). A character with might 10, however, but in the 4th tier, could potentially succeed even in a difficulty 10 task, even though he would be exhausted afterwards. This is because the amount of effort one can make depends on his tier.

Attributes then aren't really meant as a measure of the fictional capacity of the character (in fact, NPCs don't have attributes as such). Rather, they are merely an abstract resource, a way to make the player's decisions matter. This kind of approach isn't uncommon in "indie" games, like The Shadow of Yesterday. Depending on your approach to RPGs, this system may be a deal breaker, though I think it is very appropriate to episodic games. I think the biggest issue it might cause comes in sandbox games. I say this because sandbox games usually require the PCs to keep making inferences and guesses from their situation, and having the PCs and NPCs work so differently in a game like this feels a bit like cheating.