RPG Codex Review: Pillars of Eternity, by PrimeJunta

RPG Codex Review: Pillars of Eternity, by PrimeJunta

Review - posted by Crooked Bee on Wed 15 July 2015, 01:10:56

Tags: Obsidian Entertainment; Pillars of EternityThis is our fourth Pillars of Eternity review because yes, we can. Feel free to check out the first three reviews, too. (This information was brought to you by the RPG Codex Choose Your Own PoE Review program.)

[Review by PrimeJunta]

With Pillars of Eternity, Obsidian Entertainment promised to bring back

"...the central hero, memorable companions and the epic exploration of Baldur’s Gate, add in the fun, intense combat and dungeon diving of Icewind Dale, and tie it all together with the emotional writing and mature thematic exploration of Planescape: Torment."

These are big boots to step into. To what extent does it succeed?

The big-picture similarities between Pillars and the IE games are obvious, and many featured already in the Kickstarter pitch. Top-down isometric camera. Six-member party. Real-time-with-pause combat. Class- and attribute-based character system. Swords and sorcery. Elves and dwarves. Dragons and dungeons. Looks that take you straight back to Icewind Dale or Baldur’s Gate 2. Pillars also has the feel of selecting and commanding units down well. Selecting a unit or a group, moving, rotating a formation, or picking a target has the same crispness and feel of immediate feedback as in the originals. The user interface has a number of small but subtle improvements, such as better support for quick keys and the ability to shift-queue commands. Switching between Baldur's Gate 2 and Pillars is almost seamless. The characters respond instantly, and there's the same pleasurable and "connected" feeling of direct control. This is where the game succeeds best, and it accounts for a lot of the praise it has received.

Drilling down into the details, however, reveals substantive differences. Combat has “sticky” melee engagement, moving the emphasis from movement to positioning. The magic and status system has no hard counters, and all classes have a broad range of active abilities they can use in combat. That is a recipe for a mixed reception.

Engagement, Engaging?

The most obvious mechanical difference between IE and Pillars combat is engagement. In Pillars, whenever a character enters melee with a unit, he engages it. Breaking engagement incurs a disengagement attack. A good deal of Pillars combat involves active use of Engagement: using your front-liners to engage the enemy to stop it from reaching your squishier characters, and rescuing your squishier characters by using a spell, an ability, or some other way to break engagement. You can even build around the movement restrictions by picking abilities like the paladin’s Zealous Charge aura or the chanter’s Blessed was Wendgridth chant.

If all the units could do was slug at each other, this would get old fast. Pillars, however, has ways of keeping the player off-balance. Shadows teleport, breaking your engagement and creating less desirable ones; Shades can summon shadows, compounding the problem. Enemy rogues Escape and reappear elsewhere on the battlefield. Knockdown or paralysis are not only debilitating on their own, but can be used to break engagement, and for the victim, incur chances of unwanted engagement. There are a lot of different types of enemies in Pillars, even by IE game standards, and they have enough special abilities to make the differences more than just cosmetic.

This gives Pillars encounters a different pace than IE encounters. There's an initial scramble for position, then things settle down as each side slugs it out and trades area-damage or crowd-control spells and abilities. You react to units outflanking, teleporting, burrowing, or being summoned to threatening positions. Then one side tips the balance, wins, and the encounter ends. Compared to the IE games, Pillars places more emphasis on selecting active abilities and less on movement and targeting. Switching engagement off with the IE mod will not make Pillars feel like Icewind Dale, either. Dealing with the mechanic is central to the moment-to-moment gameplay experience.

Bring Your Own Camping Supplies

Another material difference between Pillars and the IE games has to do with resource conservation: damage, healing, resting, and death. The originals had a very simple system: if your health bar hits zero, you die. You can rest anywhere, at any time, although you might get interrupted by wandering monsters.

This system can be highly enjoyable, provided you adjust your game to suit it. However, it invites simple and rote exploits, such as abusing the savegame system to avoid wandering monsters while resting before every fight. It also makes a party member going down into an effective reload trigger, given the sheer tedium of trekking back to town for a resurrection: the objective isn’t as much to win a fight, but to win a fight with the full party standing. Pillars was designed to minimise such situations, pushing the player directly into finding the better and more fun ways of playing the game.

This thinking shows especially clearly in Pillars' health, death, and resting mechanics. Instead of potions and spells, we get two health bars: Endurance, quick to drain and quick to replenish after each combat, and Health, slower to lose but harder to regain. This makes the health bar one important determinant of the length of the "adventuring day:" if one of your party is Wounded, you have to rest immediately, or risk permanently losing him. There is no “party resource” health like AD&D’s cleric heals. Resting is restricted by Camping Supplies. You can carry four on easier difficulties, two on harder ones. Although you often find enough supplies in the wilderness to rest reasonably often, this does place some limitation on your behaviour.

The restricted resting and dual health mechanic pushes players who played through the IE games by rest-spamming into managing resources strategically. Little twists like skill, defence, or attribute bonuses for resting in more expensive rooms at inns or your upgraded stronghold further reinforce this, as you’ll want to keep them up as long as possible.

The strategic resource management aspect of the game can be greatly diluted by your party composition. Priests, druids, and wizards have semi-Vancian casting, with a limited number of spells per rest. Most other classes rely heavily on per-encounter abilities. If you have a party with few or none of the former, you will be entering combat with more or less the same abilities every time. This does not mean that Vancian-like casters are an ignorable exception, however: they have the broadest range of powerful abilities for any class, and if you just “go with the flow” when recruiting party members, you will end up with at least two in the party fairly early on in the game.

Rock, Paper, Fireball

The Infinity Engine games made great use of one of D&D’s best features: magic. By the time BioWare began making its games, the ruleset had been played for over 20 years, and it was massive, flexible and polished. It offered plenty of tools, from opening locked doors to protecting yourself against the petrifying gaze of a basilisk, to sequencers releasing a number of spells at once, or preparing contingency spells that automatically fire off others in specific situations.

It is not without its flaws, however. It is extremely limited at low levels, and tends towards instant-win or instant-lose effects in the mid levels. It has a quite a lot of spells which are as good as useless, and only really hits its stride at late mid to high levels, when you have a significant amount of spellcasting oomph available, both in range and quantity. That’s when the famous ‘mage duels’ start.

The growth curve of Pillars magic is the opposite. It is highly useful and has a lot of variety straight out of the gate. Where Baldur’s Gate mages would rack up a few dozen misses with a sling on an average day, Pillars’ level 1 casters are already full participants in encounters. By the time IE game magic would start to really hit its stride, towards the end of Pillars, underlying weaknesses start to emerge, and it never develops the depth and emergent complexity of a Baldur's Gate 2. There are four main causes for this: the core resolution mechanic, status effect impact and duration, the inability of the AI to exploit the synergies in the system, and limited counters.

All of Pillars' combat is based on the same resolution mechanic: you make an attack with some Accuracy against some Defence, resulting in either a Miss, a Graze, a Hit, or a Crit. With direct damage, a Graze does less damage than a Hit, while a Crit does more. With status effects, Crits increase the duration, while Grazes reduce it. To play effectively, you have to target the enemy’s weakest Defence with your strongest attack, perhaps to debuff another Defence which then lets you do real harm. On their own, many debuffs are rather trivial — a 2 point penalty to DEX or Will, for example — but combined with attacks that target the weakened Defence, they can double your party’s damage output, or make a previously impregnable enemy vulnerable to your spell. The key to playing Pillars efficiently is to look for and identify these synergies and hit the enemies with one-two punches.

The flip side is that once you do understand where to look for them, you will discover some abilities that are rather too powerful. This is exacerbated by hard-to-notice bugs which make some of them even more powerful than intended. The specifics have already changed a number of times with balance patches and are likely to continue to do so, but with a system like Pillars’, they are unlikely ever to be completely eliminated.

This standard resolution mechanic also leads to problematic behavior with status effects. Consider Slicken, a first-level wizard spell with an area effect knockdown. Since Accuracy goes up with wizard level, Slicken is likely to score a Graze even on very high-level enemies, and since the duration is quite short to start with, there's little difference in practice between Graze, Hit or even Crit. High-level wizards get to cast first-level spells per-encounter, with no strategic cost. This means that often the most efficient way to play a high-level wizard is to chain-cast Slicken in every fight, while the rest of the party pummels the prone enemies to death. It is also rote, repetitive, and not much fun. This makes spells and abilities applying status effects too powerful across the board. The problem could have been solved by having Grazes downgrade the status effect rather than reducing the duration: turning Paralysed into Stunned, Stunned into Stuck, Stuck into Dazed, and so on.

Ironically, being on the receiving end of these status effects is much less punishing, because the AI is not capable of following through with attacks that make use of them. This is exacerbated by a number of bugs or misfeatures, such as Charmed party members becoming passive rather than attacking their comrades. lt is too easy to ‘wait out’ status effects and brute force the enemies to submission. This makes for a significant asymmetry between the player and the AI, making the game a good deal easier than it ought to be. Smarter AI would be ideal; a technically simpler alternative is to have asymmetrical numbers causing enemy status effects to bite harder than what’s available to the player.

Damage over time (DOT) status effects have a different problem: in many cases, the numbers have been nerfed to insignificance. Poisoned, for example, does so little damage so slowly that most of the time it can be safely ignored, and if not, the second-level Priest spell Suppress Affliction will counter it. This is a balancing problem, and not something inherent to the design: during the backer beta, several builds featured poison attacks that were potent threats, and Path of the Damned, which boosts enemy stats, noticeably mitigates this.

Pillars’ gameplay would be much improved if status effects had clear and significant impact both in the hands of players and of enemies. This would require a broader variety of ways to counter them, pre-emptively or after the fact. Spells or abilities that increase movement speed could also counter Hobbled, Stuck, or Paralysed, for example, Divine Radiance could counter Blinded, and so on.

One last point is the relative poverty of high-level magic. While Pillars’ casters are more varied and fun to play in lower levels, their high-level portfolio pales in comparison to IE games. I hope Obsidian overhauls the magic system for higher-level sequels, as there is a real risk of it becoming rote fireworks rather than a source of emergent tactics and gameplay. Sequencers, contingencies, or other ways to combine, modify, or empower spells would make high-level magic a great deal more engaging, as would more impactful status effects and more varied ways to prevent or counter them.

Despite the weaknesses, Pillars’ magic and spell-like special abilities work together well enough. There are a lot of features to explore, synergies to discover, and tactics to hone. The system is complex enough to serve as a foundation for rich and varied gameplay.

Stealth, Needs Work

Early on in the development process, Obsidian decided to implement stealth as a game state, like combat. This led to some unfortunate consequences. It ruled out re-stealthing in combat, and made stealth full-party only — something Obsidian have admitted they are unhappy with, and have promised to overhaul in future releases. This makes the classic IE game stealth tactic — backstab — much weaker than in the IE games, as you can only use it in the opening or by expending uses of the two-per-rest Shadowing Beyond ability. For everyone else, stealth is exceedingly powerful: even with zero ranks in it, it reduces the party’s detection radius below visual range, which means that it is possible to sneak into position against any enemy with no investment in Stealth at all. Most enemies stand still until detected rather than patrolling or moving around, which aggravates the problem.

While stealth is far from perfect in the IE games—I find having to repeatedly attempt to hide aggravating rather than fun, and therefore only start use stealth tactics at all when I have my scout's stealth skills up near 100%—Pillars' system is not an improvement. Its failings would be fairly easy to address once the "game state" restriction is removed. At a minimum, effective use of stealth should need a more significant investment in the character build, and you should need a dedicated scout to be able to scout ahead. For example, have stealth only slow down the detection time to start with, and only reduce the detection radius at higher ranks.

Core Gameplay Issues

There are a few, but ultimately relatively minor issues marring the core gameplay experience. Due to the lower camera angle and overly flashy FX, it sometimes becomes hard to see what's going on: here, aesthetics took precedence over playability. The largest core gameplay wart still remaining after a few patches, however, is pathfinding. In combat, characters will sometimes bump into each other, start running back and forth, or pick a different target than the one you assigned. This is by no means so bad that it makes things seriously difficult to control, and it is possible to work around it by judicious use of reach or ranged weapons and positioning. Nevertheless, it is an irritating flaw, and one I hope Obsidian will eventually fix in a patch.

Let Us Celebrate Our Differences

Class-based RPG systems must strike a balance between differentiation between classes and variety within them. The original core D&D classes were well differentiated but extremely rigid. Pillars gave itself a clear mission: create 11 distinct classes, and yet make each one amenable to being built ‘against type’.

Pillars' classes are, for the most part, well differentiated. Fighters, rangers, barbarians, and paladins all "feel" materially different, with different active, passive, and modal abilities that require different tactics to use effectively in combat. You can build a fighter to engage up to four enemies at a time, thereby becoming a one-man frontline. A paladin built for defence is even more durable, and comes with auras and abilities to help other party members, at the cost of less control over engagement. A barbarian will do more damage and is especially effective in a crowd, but is a good deal more fragile than either. Likewise for the caster classes. Alongside semi-Vancian staples we have Ciphers, who gather Focus by hitting enemies, and Chanters, who chant Phrases applying group buffs or debuffs until they can cast an Invocation.

There is more wiggle room within the classes than in AD&D, and arguably more than in D&D3 with its clearly-signposted paths to Prestige Classes. You can build durable rogues, ranged paladins and more. Priests of particular gods can take special abilities that let you turn them into narrowly-focused but effective melee or ranged combatants rather than pure support spellcasters. Wizards and druids can play different combat roles through their spell selection as much as their build. With a grimoire full of self-buffs and summoned weapons, the wizard becomes a murderously effective if strategically costly arcane knight; with a different grimoire, he’s a disabler and debuffer that makes others do the damage, while a third gives him traditional back-row glass cannon abilities. There's a lot of room for creativity and exploration with builds, party compositions, and tactics.

Both the IE games — especially Baldur’s Gate 2 and Beamdog’s Enhanced Editions — and Pillars offer a great deal of build variety. The way they offer it is quite different, however. With BG2, you get to pick from a big menu of pre-designed classes and kits, but after that, development is on rails. With Pillars, you assemble your own dish from a buffet of ingredients and season it as you go.

Balance In All Attributes

Attributes serve a dual purpose in role-playing games. They define character concepts, and produce mechanical effects used to create builds. The former is reflected in the ways attributes are referenced in game content like dialogues and Pillars’ choose-your-own-adventure interludes, and the latter modifies the way the characters behave in combat.

In AD&D, each class has an optimal stat distribution. Mechanically, fighters have no use for INT, wizards only use STR to be able to carry more stuff, and only paladins need CHA — just because the rules say so. Pillars wanted to change this. The goal was to have all stats useful for all classes, with no obvious dump or pump stats.

The attributes underwent a lot of iteration over the course of development and the backer beta, and the result is a somewhat uncomfortable fit between these two purposes. The effects of the attributes are counterintuitive and hard to remember, the companions' stat distributions don't always reflect the companion concepts very well — the Grieving Mother, for example, is clearly intended to be more intuitive and perceptive than intellectual, yet her INT is higher than her PER — and the way they are referenced in dialogs and the CYOA interludes are poor matches for what they’re supposed to mean for various classes. Might, for example, is keyed to feats of physical strength and intimidation, even though the developers took pains to explain that mighty wizards aren’t necessarily supposed to be muscular. There also aren’t all that many CYOA’s, and it is easy to bypass any of the skill or attribute checks by using a commonly-available expendable resource. From the point of view of character concept support, the attributes do markedly worse than D&D’s familiar STR-DEX-CON-INT-WIS-CHA.

The attribute system is more successful in achieving its second goal, build diversity. A low-INT spellcaster will be much less effective with his crucial AoE spells, a low-RES frontline fighter will not be able to get much damage done due to being constantly interrupted, while high PER will enhance a barbarians’ survivability by interrupting surrounding enemies so they will be able to get fewer attacks in. DEX and MIG boost damage output for any class, and some classes, notably monks and barbarians, benefit differently from a broad range of stats. Even so, there are a few obvious pump or dump stats: CON is of little importance for most classes and builds, while low-INT wizards and druids will be seriously handicapped by having much smaller areas of effect and no “foe only” fringes on their best spells.

Fun: Allowed

Despite some flaws in the specifics, Pillars’ character system coheres into a whole which supports many fun ways of playing the game. All the classes are effective and genuinely different. Each of them develops in a unique way when leveling up, and allows for meaningful build choices when doing so. Swapping characters in or out of the party forces you to adjust tactics accordingly. You can build hard-hitting fighters, tanky rogues, melee rangers, Interrupt-based frontliners, firearms specialists, master archers, and many others that don’t follow the obvious class template. You can still build the most obvious of parties, but if you like to experiment, you have the freedom to do so. The “no bad builds” goal (if it ever was one) may not have been reached, but Pillars’ classes have room for much more creativity than it may appear at first glance.

A Handful of Estocs

Pillars is a Monty Haul kind of game. There's a lot of junk thrown at you all the time, and you have an unlimited stash where you can dump it before selling it off. The weapon focus/specialisation system, based on weapon groups rather than individual weapons, lets you make the most of the better stuff you find. Truly top-tier items are rare, but there's enough stuff in the game that whatever focus you pick, you will find something you can use effectively sooner rather than later. Actively hunting for something good is only a concern early in the game; once past the first chapter, it's a matter of choosing which goodie to use.

Pillars also attempts to capture the IE magic by having hand-written descriptions and back-stories on otherwise relatively mundane items, many of which were designed by high-tier backers as rewards. It does not entirely succeed.

The main problem is lack of differentiation and sheer quantity. There are so many unique items that they don't feel all that unique anymore, and a lot of backer-created items are just pointless and jarring. While no two uniques are exactly alike, many are interchangeable. With fewer unique items, finding one would have felt like an occasion rather than something you glance at and throw in the stash to sell off later.

Pillars also has a few extra-special items that you assemble or acquire through questing. Regrettably, they turn out to be just another unique item just like all the other unique items. In Baldur's Gate 2, weapons like Carsomyr, Crom Faeyr, or Celestial Fury are so memorable because they really are unique—special enough that it's worth building a character just to use them, once you know about them and how to get them. Pillars could have captured some of that magic simply by adjusting the numbers on those extra-special items, making them genuinely covetable. Here, Balance really does step on Fun's toes.

These problems are exacerbated by a weak subsystem: crafting and enchantment. The intent is to make it possible to enhance items you like as you go, rather than discarding them for something better. Its problem is that it is too easy and not restrictive enough. Enchanting uses junk you find in the world to apply properties to items. You can do it at any time, anywhere, there are no skill requirements (although there is a level requirement), and you know all the recipes. You can even confer properties like Fine, Exceptional, and Superb, which I would have expected to be base characteristics that determine the degree to which items can accept enchantments. In the first part of the game, enchantment components are rare enough that you won’t always be able to tailor items to taste; in the second half, the only ones you will be lacking are components for Superb—the equivalent of +5 in Baldur’s Gate 2.

At its best, a good crafting/enchantment system is a driver for self-directed, emergent gameplay. The hunt for the right component, recipe, or craftsman is a quest in its own right, and you get a massive kick when you finally find what you need. Pillars' crafting system does not achieve that. While it is a useful subsystem than handily complements your character-building and tactical choices, that is all it is. With a better, more focused, and more restrictive crafting/enchantment system and fewer named items, itemisation could have been much more — something that in and of itself directs and motivates gameplay. Sometimes more is more, but sometimes less is more, and when it comes to items and crafting, less would have been more.

Much Is Good, More Is Better

A game is more than mechanics. Good mechanics are useless without content to support them, while poor ones can be worked around. Subsystems are only any use if they're referenced, and flaws only become annoyances to the extent the content pushes you into them.

Pillars' content supports the mechanics relatively well. Most spells and special abilities are genuinely useful in combat and there is room for a lot of experimentation with different parties, character builds, and tactics. Outside combat, your choices in character-building and story are acknowledged with unique dialog options or CYOA interactions. The developers have taken care to ensure that all skills get uses, all dispositions and reflected in dialogs, and pumping any attribute gets acknowledged.

Combat encounters are thematically consistent but varied, with lots of different types of enemies with distinct special abilities, coming at you in different combinations and letting you make use of all those spells, specials, and gear you've collected on the way. Even “trash” enemies like xaurips come in a range of flavours: ordinary scrubs, skirmishers with a nasty paralysing attack, harder-hitting champions, and priests bombarding you with area-effect damage. A group of ogres may include druids casting spells that can effectively silence your spellcasters while doing serious amounts of damage over time. Same for oozes of various sizes and colours, incorporeal undead that range from the somewhat annoying shadows to seriously scary totally-not-banshee cêan gŵla. Corporeal undead — “vessels” in Pillars parlance — show up in groups which include archers, melee combatants, casters, and fampyrs which not only regenerate fast but are able to charm party members. There are a couple of areas with rather a lot of similar enemies — a lord’s castle has lots of guards, a cultists’ secret temple has lots of cultists — but they’re relatively infrequent, and in those cases the obvious quest solution is usually to not fight them all.

Yet there are missed opportunities as well. Some of the most memorable encounters in Baldur’s Gate 2 featured the environment as much as the monsters. Sadly, Pillars has no counterpart for Firkraag’s dungeon with its flanking orc archers, close-quarters ambushes, or wolfweres luring the hapless party into a trap, despite the beautiful possibilities offered by the Engwithan ruins where much of the action takes place. The best we get is a couple of fights in areas with some traps scattered around, which we can’t disarm during combat, presumably due to the “game state” implementation of stealth.

Fights between adventuring parties are underwhelming, especially on difficulties below Path of the Damned. These are among the toughest and most varied in Baldur's Gate 2, but in Pillars, with a couple of notable exceptions in the first act when they're between low-level parties, they're too easy. This is largely due to deficiencies in the AI: enemy parties don't manage to support each other with their abilities as efficiently as they should, and it’s easy to take out the crucial spellcasters early on.

On the whole, the game’s encounter variety is let down by its difficulty level. At difficulties up to Hard they just don’t push you past the point of discovering a few standard tactics that work well enough, and it’s easy to get caught in a rut of repeating them until the endgame. There are more efficient — and more fun — ways to play, but you have to dial it up to Path of the Damned to get any push from the game to discover them.

Your Kind's Not Welcome In These Parts

Instead of a D&D alignment, Pillars tracks your reputation with various factions, and your disposition — what kind of person people think you are. Disposition is extremely important for paladins and priests, as a disposition which aligns with your ethos strengthens your best special abilities. For everyone else, it's mostly flavour: dialog choices that open up, sometimes offering shortcuts, alternative solutions, or information you would otherwise have missed.

Some of the lustre comes off the disposition system if you make the numbers visible and pay close attention to the reputations and dispositions you're acquiring, turning it into a minigame. Playing as a paladin is much more engaging if you have to figure out "blind" how to play to your order's favoured dispositions, rather than just reflexively picking "Diplomatic" and "Honest" whenever they're offered. I tried this a good way into Chapter 2 with a Shieldbearer of St. Elcga, and while I didn’t get a “perfect score,” I did rack up most ranks in the dispositions I was targeting, and none in the ones I was avoiding.

There are also missed opportunities. If you play as a priest of one of the gods figuring in the game's story, your status will be acknowledged every now and then, but relatively superficially. If a plotline throws you into conflict with other priests of the god you serve, you won't be able to side with them from the get-go, and there are occasional silly moments like a priest of Eothas offered a dialog line, “Who’s Eothas?”

The faction reputation system is based on what you do rather than what you say or how you do it. It is a traditional affair, where you gain reputation with a faction by doing stuff for them, and lose it by aligning with an opposing faction, or doing things that go against their interests. This is only really significant in the mid-game, where you can only progress after deciding which Defiance Bay faction to align with. These choices are also let down by a forced plot twist, although their long-term consequences are explored in the endgame slideshow.

The overall effect is nice but fairly subtle. You do feel that the game acknowledges the particular choices and characteristics that make Charname unique, better than in most cRPG's, including the Infinity Engine ones. It makes the world feel alive and that the way you built your character and interact with the world matter. The main narrative, however, is more linear than you might expect, and because of the mixed Disposition you will likely accumulate, your experience in different playthroughs will not change all that much. This is no Fallout: New Vegas, but nor is it an Icewind Dale.

Off The Level

Overall, Pillars is somewhere between the IE games and modern mainstream expectations in difficulty. I was playing Pillars and Baldur's Gate 2 concurrently, spending a few days or a week on one, then the other. I had Pillars on Hard and Baldur's Gate 2 on Core Rules, and the challenge level felt roughly similar; I was winning and losing encounters at about the same frequency, and my "adventuring day" felt about equally long, although Baldur’s Gate 2’s hardest optional encounters were tougher than Pillars’, and permadeath meant a good deal more reloading. On Path of the Damned, the harder encounters were close to Baldur’s Gate 2 hard, especially in the early game.

Difficulty swings somewhat through the game. Parts of Chapter 1 can be punishingly hard if you go after them early, as can be parts of Chapter 3 if you’ve mostly just followed the main quest’s breadcrumb trail. Apart from a few optional encounters, Chapter 2 becomes easy towards the end as you gain levels and items, in whichever order you play it. By modern mainstream standards Pillars is a pretty hard game; by the standards of 15 years ago, or the likes of Blackguards or Dwarf Fortress, it is on the easy side.

The Endless Paths of Od Nua and the bounties on offer at your stronghold — Kickstarter stretch goals, both of them — can make a real mess of the power curve. Do the side content everywhere else, and you will hit the endgame with a couple of party members still hungry for another level. Dive into the megadungeon, and when you come out, you will be outleveled and out-geared for what’s left of the game.

Path of the Incline

Unlike most games these days, difficulty levels up to Hard don’t change the rules or the enemy stats in any way. Instead, you get tougher variants of enemies in bigger groups — adra beetles in addition to stone and wood beetles, shadows upgraded to shades, shades to phantoms, guls to darguls, darguls to fampyrs, and so on. Only the hardest level, billed as a special challenge for the truly hardcore, adjusts the numbers.

That’s a shame, because on Path of the Damned Pillars plays a lot more like it ought to. Status effects start biting. Enemies have hard enough defences that attacking them with the right combinations is often a requirement. They hit hard enough that repeating good-enough tactics won’t always cut it. You start paying serious attention to consumables and crafting. And even so, some of the optional fights are truly punishing, at least if you go into them early.

Pillars suffers from the design decision to produce difficulty levels by changing the encounter composition rather than adjusting the numbers. Casual players who can’t be bothered to learn the mechanics at all will find Easy frustratingly hard, whereas more experienced players will soon snooze through Hard by mechanically applying a good-enough strategy they happened upon. There are more efficient and more fun ways to play, but the game leaves it up to you to discover them.

The game would likely have been received a good deal better among the hardcore crowd if Hard had been more or less like Path of the Damned with, perhaps, the mobs a little smaller, and another, even higher difficulty level above it, or a second difficulty slider tuning the numbers so it would have been possible to play against Hard enemies with Path of the Damned rules. As it is, Path of the Damned is the most enjoyable difficulty level in the game, but it doesn’t live up to its billing as a Heart of Fury spiritual successor.

A Brave New World

The world of Pillars — Eora — reproduces many features familiar from Forgotten Realms and other classic D&D settings. It has dwarves and elves, dragons and dungeons, restless dead wandering the night, ancient ruins, quaint villages, and even a big city or two. It is far more coherent and believable than most similar settings, however. Wars are fought for understandable reasons: a culture sending colonists to encroach on another's ancestral land; a religious pogrom; a colony breaking off from a declining empire. The world is dynamic and changing. Animancers are making discoveries which promise to revolutionise medicine, warfare, and even religion. Vailian traders ply the seas in their caravelles, and Rauatai’s foundries turn out cannon for their warships. Where traditional fantasy is conservative in outlook, ever looking back to a lost golden age of ancient empires, Eora looks forward, to new discoveries, technologies, and knowledge.

Eora also breaks with some hoary fantasy tropes. Race no longer equals culture. Rather, cultures are multiracial, and some even have institutionalised forms in which the races interact. It draws from a broader range of traditions than is usual for Western traditional fantasy: we meet cultures inspired by the Inuit and the Polynesians. The world has several constructed languages, with Celtic, Romance, Inuit, Old English, or Polynesian echoes. The overall impression is coherent, layered, and living; an impressive achievement especially considering that it was created from scratch in less than two years.

Pillars of Eternity features eight companions. Each of them comes with an internal conflict and a quest you can pursue to help them resolve it. The companions are written well, thoughtfully characterised, sympathetic, and original, and feature a fair amount of character-specific content. Pillars does not feature Baldur’s Gate 2’s complex intra-party interactions, however. Edér and Durance may have serious reasons to hate each other, but neither will walk out on you no matter what you do, Aloth won’t fall in love with Pallegina, and you won’t be able to romance any of them. Nor are the character arcs as complex or branching as in Baldur’s Gate 2 or Planescape: Torment: completing them is a matter of following the breadcrumb trail rather than making difficult choices.

The main narrative is a more standard affair than the companions. There is the initial catastrophe, the charismatic but elusive antagonist, the plot twist, and the climax, resolved according to your choices over the course of the game. It is not without its problems — what if I think being a Watcher is just peachy and want to learn to exploit it rather than cure it? — but it gets the job done, holding together the small stories, quests, and details that make up the game. Worth noting is the excellent voice acting for the main antagonist: like David Warner with Jon Irenicus, Josh Brolin makes Thaos’s villain speeches sound like he means it.

Pillars is a beautiful game, both in looks and in sound. Justin Sweet’s largely live-performed score is especially worthy of note. It is obvious that much love went into crafting it. The budget limits only show up if you look more closely: animations are not AAA-level fluid or realistic, the FX are often on the crude side, and zoomed-in the character models are a bit chunky. Overall, Pillars looks and sounds like a natural evolution of the IE games to modern graphical standards. Art and music matter, and here, occasional lacunae in character art aside, Pillars shines.

The Agony and the Ecstasy (of Kickstarter)

Kickstarter is often touted as freeing studios from publisher tyranny, letting them pitch their games directly to the fans, and make them like they want them. At its best, it can really work this way, as publishers like inXile and Hairbrained Schemes have demonstrated. This first generation of big-ticket Kickstarter role-playing games have already carved out a whole new niche: big, complex games made for RPG fans, with higher production values than indie games made on a shoestring budget. There is a danger, however, of falling into another trap: making promises to the fans which turn out to be difficult to keep, or just plain bad ideas. Pillars is a good illustration of both sides of the Kickstarter coin.

The good is that the game got made in the first place. According to Obsidian, publishers simply haven't been interested in funding games of this type, scope, and budget range. Managing Kickstarters is hard, however, and it's not just about raking in the money. Many of Pillars' flaws can be traced back to the poorly-planned and largely improvised Kickstarter campaign.

With its unexpectedly fast success, Obsidian scrambled to come up with stretch goals and backer rewards. The campaign offered high-ticket backers the possibility to create vanity content: not just easily ignorable tombstones, but NPC's, character portraits, items, and even inns. Almost all of that content is, frankly, garbage, adding nothing of value to the game, and causing problems like the proliferation of interchangeable “unique” items. The backer NPC’s standing around in their flashy armour with their heads on fire are spectacularly out of place, and finding a corporate logo as an inn sign is too close for comfort to paid in-game advertising.

Worse, however, were some of the stretch goals. In particular, the stronghold, the megadungeon, and the proliferation of classes.

The stronghold, designed by Tim Cain, feels unfinished and entirely unnecessary. The mechanics are sound enough, but there's no flesh around those bones. You can park companions there and send them on adventures to gain experience and items, but those adventures have no meat to them at all: they are labeled "Average Adventure" offering rewards like "10% XP and a minor reputation bonus." Periodically the stronghold gets attacked by generic “bandits” of unspecified origin. The Baldur's Gate 2 strongholds didn't have Caed Nua's mechanical underpinnings, but they had unique, hand-written quests with characterful rewards. That made them fun, where Caed Nua is lifeless and dull.

The megadungeon is much better executed than the stronghold, and it's an enjoyable enough — if somewhat uneven — dungeon crawl in its own right. Its problem is that it messes up the power curve. Play it through, and you'll outlevel and out-gear the rest of the game. The stronghold and megadungeon should have been expansions; a Durlag's Tower or Watcher's Keep, thrown in for players who want to keep playing a bit longer with their high-level characters. As it is, they are a distraction, both for the player and for the game's makers. The weaker subsystems in the game — crafting and stealth, in particular — just need more work. Without Caed Nua, Od Nua, and the other irrelevant content introduced as stretch goals and backer rewards, I'm sure they would have been able to bring them to a higher standard.

Under the hood, Obsidian has created a robust system of combat and character mechanics—though not without its problems. Regrettably, that system is let down by poor overall balancing. Most status effects have been nerfed to insignificance, and the difficulty, for veteran players, encourages boring play. The magic system has similar problems. It works well enough especially in the early part of the game, but towards the late game, the cracks start showing. It gets the job done — just — for Pillars, but an overhaul for higher-level sequels would be most welcome.

Even with its flaws, Pillars of Eternity is a remarkable game. It was made in a short time with limited resources, yet it is as big, sprawling, complex, and detailed as the games it references. The world is deep, fully-realised, and more believable than Forgotten Realms or most other swords-and-sorcery settings. The gameplay is rich and varied, with massive scope for experimentation and creativity, and if you crank it up to Path of the Damned, challenging enough to keep you on your toes for most of the ride. The writing is up to Obsidian's usually high standard. And there's a lot of it: masses of quests, monsters, maps, dialogues, items, abilities, and much more.

Baldur's Gate would likely have been forgotten had it not been for Baldur's Gate 2 and Planescape: Torment. If Obsidian can build on Pillars' success, improve on the areas that need improvement while maintaining its strengths, Path of the Damned can point the way to Path of the Incline. Pillars is a first, somewhat faltering step to reviving a near-stagnant genre. A few years ago, the very idea of a Baldur’s Gate 2-scope, top-down, isometric, party-based cRPG from a major studio seemed like a pipe dream. Whether this new flowering can survive between the siren song of a mass market and the grumbling of the grognards — let alone come close to making both groups happy — hangs on the followup. For some of us, Pillars delivered. Others are still waiting. The space it and the other big-ticket Kickstarters has helped clear benefits us all.

Review edited by Tigranes, screenshots by Gord.

[Review by PrimeJunta]

With Pillars of Eternity, Obsidian Entertainment promised to bring back

"...the central hero, memorable companions and the epic exploration of Baldur’s Gate, add in the fun, intense combat and dungeon diving of Icewind Dale, and tie it all together with the emotional writing and mature thematic exploration of Planescape: Torment."

These are big boots to step into. To what extent does it succeed?

The big-picture similarities between Pillars and the IE games are obvious, and many featured already in the Kickstarter pitch. Top-down isometric camera. Six-member party. Real-time-with-pause combat. Class- and attribute-based character system. Swords and sorcery. Elves and dwarves. Dragons and dungeons. Looks that take you straight back to Icewind Dale or Baldur’s Gate 2. Pillars also has the feel of selecting and commanding units down well. Selecting a unit or a group, moving, rotating a formation, or picking a target has the same crispness and feel of immediate feedback as in the originals. The user interface has a number of small but subtle improvements, such as better support for quick keys and the ability to shift-queue commands. Switching between Baldur's Gate 2 and Pillars is almost seamless. The characters respond instantly, and there's the same pleasurable and "connected" feeling of direct control. This is where the game succeeds best, and it accounts for a lot of the praise it has received.

Drilling down into the details, however, reveals substantive differences. Combat has “sticky” melee engagement, moving the emphasis from movement to positioning. The magic and status system has no hard counters, and all classes have a broad range of active abilities they can use in combat. That is a recipe for a mixed reception.

Engagement, Engaging?

The most obvious mechanical difference between IE and Pillars combat is engagement. In Pillars, whenever a character enters melee with a unit, he engages it. Breaking engagement incurs a disengagement attack. A good deal of Pillars combat involves active use of Engagement: using your front-liners to engage the enemy to stop it from reaching your squishier characters, and rescuing your squishier characters by using a spell, an ability, or some other way to break engagement. You can even build around the movement restrictions by picking abilities like the paladin’s Zealous Charge aura or the chanter’s Blessed was Wendgridth chant.

If all the units could do was slug at each other, this would get old fast. Pillars, however, has ways of keeping the player off-balance. Shadows teleport, breaking your engagement and creating less desirable ones; Shades can summon shadows, compounding the problem. Enemy rogues Escape and reappear elsewhere on the battlefield. Knockdown or paralysis are not only debilitating on their own, but can be used to break engagement, and for the victim, incur chances of unwanted engagement. There are a lot of different types of enemies in Pillars, even by IE game standards, and they have enough special abilities to make the differences more than just cosmetic.

This gives Pillars encounters a different pace than IE encounters. There's an initial scramble for position, then things settle down as each side slugs it out and trades area-damage or crowd-control spells and abilities. You react to units outflanking, teleporting, burrowing, or being summoned to threatening positions. Then one side tips the balance, wins, and the encounter ends. Compared to the IE games, Pillars places more emphasis on selecting active abilities and less on movement and targeting. Switching engagement off with the IE mod will not make Pillars feel like Icewind Dale, either. Dealing with the mechanic is central to the moment-to-moment gameplay experience.

Bring Your Own Camping Supplies

Another material difference between Pillars and the IE games has to do with resource conservation: damage, healing, resting, and death. The originals had a very simple system: if your health bar hits zero, you die. You can rest anywhere, at any time, although you might get interrupted by wandering monsters.

This system can be highly enjoyable, provided you adjust your game to suit it. However, it invites simple and rote exploits, such as abusing the savegame system to avoid wandering monsters while resting before every fight. It also makes a party member going down into an effective reload trigger, given the sheer tedium of trekking back to town for a resurrection: the objective isn’t as much to win a fight, but to win a fight with the full party standing. Pillars was designed to minimise such situations, pushing the player directly into finding the better and more fun ways of playing the game.

This thinking shows especially clearly in Pillars' health, death, and resting mechanics. Instead of potions and spells, we get two health bars: Endurance, quick to drain and quick to replenish after each combat, and Health, slower to lose but harder to regain. This makes the health bar one important determinant of the length of the "adventuring day:" if one of your party is Wounded, you have to rest immediately, or risk permanently losing him. There is no “party resource” health like AD&D’s cleric heals. Resting is restricted by Camping Supplies. You can carry four on easier difficulties, two on harder ones. Although you often find enough supplies in the wilderness to rest reasonably often, this does place some limitation on your behaviour.

The restricted resting and dual health mechanic pushes players who played through the IE games by rest-spamming into managing resources strategically. Little twists like skill, defence, or attribute bonuses for resting in more expensive rooms at inns or your upgraded stronghold further reinforce this, as you’ll want to keep them up as long as possible.

The strategic resource management aspect of the game can be greatly diluted by your party composition. Priests, druids, and wizards have semi-Vancian casting, with a limited number of spells per rest. Most other classes rely heavily on per-encounter abilities. If you have a party with few or none of the former, you will be entering combat with more or less the same abilities every time. This does not mean that Vancian-like casters are an ignorable exception, however: they have the broadest range of powerful abilities for any class, and if you just “go with the flow” when recruiting party members, you will end up with at least two in the party fairly early on in the game.

Rock, Paper, Fireball

The Infinity Engine games made great use of one of D&D’s best features: magic. By the time BioWare began making its games, the ruleset had been played for over 20 years, and it was massive, flexible and polished. It offered plenty of tools, from opening locked doors to protecting yourself against the petrifying gaze of a basilisk, to sequencers releasing a number of spells at once, or preparing contingency spells that automatically fire off others in specific situations.

It is not without its flaws, however. It is extremely limited at low levels, and tends towards instant-win or instant-lose effects in the mid levels. It has a quite a lot of spells which are as good as useless, and only really hits its stride at late mid to high levels, when you have a significant amount of spellcasting oomph available, both in range and quantity. That’s when the famous ‘mage duels’ start.

The growth curve of Pillars magic is the opposite. It is highly useful and has a lot of variety straight out of the gate. Where Baldur’s Gate mages would rack up a few dozen misses with a sling on an average day, Pillars’ level 1 casters are already full participants in encounters. By the time IE game magic would start to really hit its stride, towards the end of Pillars, underlying weaknesses start to emerge, and it never develops the depth and emergent complexity of a Baldur's Gate 2. There are four main causes for this: the core resolution mechanic, status effect impact and duration, the inability of the AI to exploit the synergies in the system, and limited counters.

All of Pillars' combat is based on the same resolution mechanic: you make an attack with some Accuracy against some Defence, resulting in either a Miss, a Graze, a Hit, or a Crit. With direct damage, a Graze does less damage than a Hit, while a Crit does more. With status effects, Crits increase the duration, while Grazes reduce it. To play effectively, you have to target the enemy’s weakest Defence with your strongest attack, perhaps to debuff another Defence which then lets you do real harm. On their own, many debuffs are rather trivial — a 2 point penalty to DEX or Will, for example — but combined with attacks that target the weakened Defence, they can double your party’s damage output, or make a previously impregnable enemy vulnerable to your spell. The key to playing Pillars efficiently is to look for and identify these synergies and hit the enemies with one-two punches.

The flip side is that once you do understand where to look for them, you will discover some abilities that are rather too powerful. This is exacerbated by hard-to-notice bugs which make some of them even more powerful than intended. The specifics have already changed a number of times with balance patches and are likely to continue to do so, but with a system like Pillars’, they are unlikely ever to be completely eliminated.

This standard resolution mechanic also leads to problematic behavior with status effects. Consider Slicken, a first-level wizard spell with an area effect knockdown. Since Accuracy goes up with wizard level, Slicken is likely to score a Graze even on very high-level enemies, and since the duration is quite short to start with, there's little difference in practice between Graze, Hit or even Crit. High-level wizards get to cast first-level spells per-encounter, with no strategic cost. This means that often the most efficient way to play a high-level wizard is to chain-cast Slicken in every fight, while the rest of the party pummels the prone enemies to death. It is also rote, repetitive, and not much fun. This makes spells and abilities applying status effects too powerful across the board. The problem could have been solved by having Grazes downgrade the status effect rather than reducing the duration: turning Paralysed into Stunned, Stunned into Stuck, Stuck into Dazed, and so on.

Ironically, being on the receiving end of these status effects is much less punishing, because the AI is not capable of following through with attacks that make use of them. This is exacerbated by a number of bugs or misfeatures, such as Charmed party members becoming passive rather than attacking their comrades. lt is too easy to ‘wait out’ status effects and brute force the enemies to submission. This makes for a significant asymmetry between the player and the AI, making the game a good deal easier than it ought to be. Smarter AI would be ideal; a technically simpler alternative is to have asymmetrical numbers causing enemy status effects to bite harder than what’s available to the player.

Damage over time (DOT) status effects have a different problem: in many cases, the numbers have been nerfed to insignificance. Poisoned, for example, does so little damage so slowly that most of the time it can be safely ignored, and if not, the second-level Priest spell Suppress Affliction will counter it. This is a balancing problem, and not something inherent to the design: during the backer beta, several builds featured poison attacks that were potent threats, and Path of the Damned, which boosts enemy stats, noticeably mitigates this.

Pillars’ gameplay would be much improved if status effects had clear and significant impact both in the hands of players and of enemies. This would require a broader variety of ways to counter them, pre-emptively or after the fact. Spells or abilities that increase movement speed could also counter Hobbled, Stuck, or Paralysed, for example, Divine Radiance could counter Blinded, and so on.

One last point is the relative poverty of high-level magic. While Pillars’ casters are more varied and fun to play in lower levels, their high-level portfolio pales in comparison to IE games. I hope Obsidian overhauls the magic system for higher-level sequels, as there is a real risk of it becoming rote fireworks rather than a source of emergent tactics and gameplay. Sequencers, contingencies, or other ways to combine, modify, or empower spells would make high-level magic a great deal more engaging, as would more impactful status effects and more varied ways to prevent or counter them.

Despite the weaknesses, Pillars’ magic and spell-like special abilities work together well enough. There are a lot of features to explore, synergies to discover, and tactics to hone. The system is complex enough to serve as a foundation for rich and varied gameplay.

Stealth, Needs Work

Early on in the development process, Obsidian decided to implement stealth as a game state, like combat. This led to some unfortunate consequences. It ruled out re-stealthing in combat, and made stealth full-party only — something Obsidian have admitted they are unhappy with, and have promised to overhaul in future releases. This makes the classic IE game stealth tactic — backstab — much weaker than in the IE games, as you can only use it in the opening or by expending uses of the two-per-rest Shadowing Beyond ability. For everyone else, stealth is exceedingly powerful: even with zero ranks in it, it reduces the party’s detection radius below visual range, which means that it is possible to sneak into position against any enemy with no investment in Stealth at all. Most enemies stand still until detected rather than patrolling or moving around, which aggravates the problem.

While stealth is far from perfect in the IE games—I find having to repeatedly attempt to hide aggravating rather than fun, and therefore only start use stealth tactics at all when I have my scout's stealth skills up near 100%—Pillars' system is not an improvement. Its failings would be fairly easy to address once the "game state" restriction is removed. At a minimum, effective use of stealth should need a more significant investment in the character build, and you should need a dedicated scout to be able to scout ahead. For example, have stealth only slow down the detection time to start with, and only reduce the detection radius at higher ranks.

Core Gameplay Issues

There are a few, but ultimately relatively minor issues marring the core gameplay experience. Due to the lower camera angle and overly flashy FX, it sometimes becomes hard to see what's going on: here, aesthetics took precedence over playability. The largest core gameplay wart still remaining after a few patches, however, is pathfinding. In combat, characters will sometimes bump into each other, start running back and forth, or pick a different target than the one you assigned. This is by no means so bad that it makes things seriously difficult to control, and it is possible to work around it by judicious use of reach or ranged weapons and positioning. Nevertheless, it is an irritating flaw, and one I hope Obsidian will eventually fix in a patch.

Let Us Celebrate Our Differences

Class-based RPG systems must strike a balance between differentiation between classes and variety within them. The original core D&D classes were well differentiated but extremely rigid. Pillars gave itself a clear mission: create 11 distinct classes, and yet make each one amenable to being built ‘against type’.

Pillars' classes are, for the most part, well differentiated. Fighters, rangers, barbarians, and paladins all "feel" materially different, with different active, passive, and modal abilities that require different tactics to use effectively in combat. You can build a fighter to engage up to four enemies at a time, thereby becoming a one-man frontline. A paladin built for defence is even more durable, and comes with auras and abilities to help other party members, at the cost of less control over engagement. A barbarian will do more damage and is especially effective in a crowd, but is a good deal more fragile than either. Likewise for the caster classes. Alongside semi-Vancian staples we have Ciphers, who gather Focus by hitting enemies, and Chanters, who chant Phrases applying group buffs or debuffs until they can cast an Invocation.

There is more wiggle room within the classes than in AD&D, and arguably more than in D&D3 with its clearly-signposted paths to Prestige Classes. You can build durable rogues, ranged paladins and more. Priests of particular gods can take special abilities that let you turn them into narrowly-focused but effective melee or ranged combatants rather than pure support spellcasters. Wizards and druids can play different combat roles through their spell selection as much as their build. With a grimoire full of self-buffs and summoned weapons, the wizard becomes a murderously effective if strategically costly arcane knight; with a different grimoire, he’s a disabler and debuffer that makes others do the damage, while a third gives him traditional back-row glass cannon abilities. There's a lot of room for creativity and exploration with builds, party compositions, and tactics.

Both the IE games — especially Baldur’s Gate 2 and Beamdog’s Enhanced Editions — and Pillars offer a great deal of build variety. The way they offer it is quite different, however. With BG2, you get to pick from a big menu of pre-designed classes and kits, but after that, development is on rails. With Pillars, you assemble your own dish from a buffet of ingredients and season it as you go.

Balance In All Attributes

Attributes serve a dual purpose in role-playing games. They define character concepts, and produce mechanical effects used to create builds. The former is reflected in the ways attributes are referenced in game content like dialogues and Pillars’ choose-your-own-adventure interludes, and the latter modifies the way the characters behave in combat.

In AD&D, each class has an optimal stat distribution. Mechanically, fighters have no use for INT, wizards only use STR to be able to carry more stuff, and only paladins need CHA — just because the rules say so. Pillars wanted to change this. The goal was to have all stats useful for all classes, with no obvious dump or pump stats.

The attributes underwent a lot of iteration over the course of development and the backer beta, and the result is a somewhat uncomfortable fit between these two purposes. The effects of the attributes are counterintuitive and hard to remember, the companions' stat distributions don't always reflect the companion concepts very well — the Grieving Mother, for example, is clearly intended to be more intuitive and perceptive than intellectual, yet her INT is higher than her PER — and the way they are referenced in dialogs and the CYOA interludes are poor matches for what they’re supposed to mean for various classes. Might, for example, is keyed to feats of physical strength and intimidation, even though the developers took pains to explain that mighty wizards aren’t necessarily supposed to be muscular. There also aren’t all that many CYOA’s, and it is easy to bypass any of the skill or attribute checks by using a commonly-available expendable resource. From the point of view of character concept support, the attributes do markedly worse than D&D’s familiar STR-DEX-CON-INT-WIS-CHA.

The attribute system is more successful in achieving its second goal, build diversity. A low-INT spellcaster will be much less effective with his crucial AoE spells, a low-RES frontline fighter will not be able to get much damage done due to being constantly interrupted, while high PER will enhance a barbarians’ survivability by interrupting surrounding enemies so they will be able to get fewer attacks in. DEX and MIG boost damage output for any class, and some classes, notably monks and barbarians, benefit differently from a broad range of stats. Even so, there are a few obvious pump or dump stats: CON is of little importance for most classes and builds, while low-INT wizards and druids will be seriously handicapped by having much smaller areas of effect and no “foe only” fringes on their best spells.

Fun: Allowed

Despite some flaws in the specifics, Pillars’ character system coheres into a whole which supports many fun ways of playing the game. All the classes are effective and genuinely different. Each of them develops in a unique way when leveling up, and allows for meaningful build choices when doing so. Swapping characters in or out of the party forces you to adjust tactics accordingly. You can build hard-hitting fighters, tanky rogues, melee rangers, Interrupt-based frontliners, firearms specialists, master archers, and many others that don’t follow the obvious class template. You can still build the most obvious of parties, but if you like to experiment, you have the freedom to do so. The “no bad builds” goal (if it ever was one) may not have been reached, but Pillars’ classes have room for much more creativity than it may appear at first glance.

A Handful of Estocs

Pillars is a Monty Haul kind of game. There's a lot of junk thrown at you all the time, and you have an unlimited stash where you can dump it before selling it off. The weapon focus/specialisation system, based on weapon groups rather than individual weapons, lets you make the most of the better stuff you find. Truly top-tier items are rare, but there's enough stuff in the game that whatever focus you pick, you will find something you can use effectively sooner rather than later. Actively hunting for something good is only a concern early in the game; once past the first chapter, it's a matter of choosing which goodie to use.

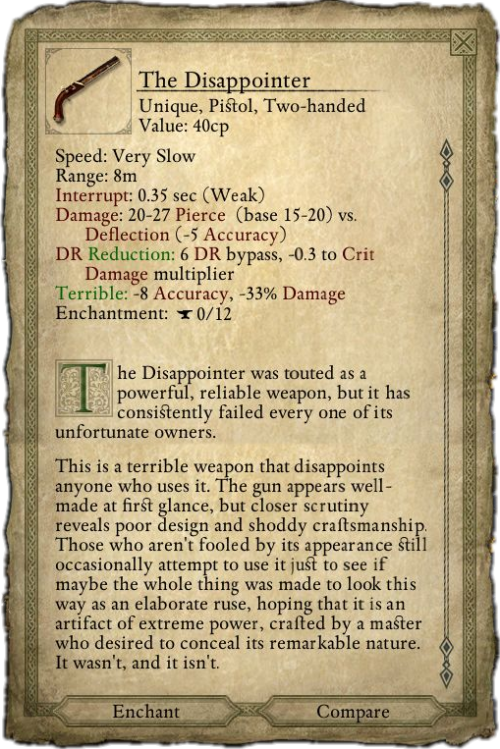

Pillars also attempts to capture the IE magic by having hand-written descriptions and back-stories on otherwise relatively mundane items, many of which were designed by high-tier backers as rewards. It does not entirely succeed.

The main problem is lack of differentiation and sheer quantity. There are so many unique items that they don't feel all that unique anymore, and a lot of backer-created items are just pointless and jarring. While no two uniques are exactly alike, many are interchangeable. With fewer unique items, finding one would have felt like an occasion rather than something you glance at and throw in the stash to sell off later.

Pillars also has a few extra-special items that you assemble or acquire through questing. Regrettably, they turn out to be just another unique item just like all the other unique items. In Baldur's Gate 2, weapons like Carsomyr, Crom Faeyr, or Celestial Fury are so memorable because they really are unique—special enough that it's worth building a character just to use them, once you know about them and how to get them. Pillars could have captured some of that magic simply by adjusting the numbers on those extra-special items, making them genuinely covetable. Here, Balance really does step on Fun's toes.

These problems are exacerbated by a weak subsystem: crafting and enchantment. The intent is to make it possible to enhance items you like as you go, rather than discarding them for something better. Its problem is that it is too easy and not restrictive enough. Enchanting uses junk you find in the world to apply properties to items. You can do it at any time, anywhere, there are no skill requirements (although there is a level requirement), and you know all the recipes. You can even confer properties like Fine, Exceptional, and Superb, which I would have expected to be base characteristics that determine the degree to which items can accept enchantments. In the first part of the game, enchantment components are rare enough that you won’t always be able to tailor items to taste; in the second half, the only ones you will be lacking are components for Superb—the equivalent of +5 in Baldur’s Gate 2.

At its best, a good crafting/enchantment system is a driver for self-directed, emergent gameplay. The hunt for the right component, recipe, or craftsman is a quest in its own right, and you get a massive kick when you finally find what you need. Pillars' crafting system does not achieve that. While it is a useful subsystem than handily complements your character-building and tactical choices, that is all it is. With a better, more focused, and more restrictive crafting/enchantment system and fewer named items, itemisation could have been much more — something that in and of itself directs and motivates gameplay. Sometimes more is more, but sometimes less is more, and when it comes to items and crafting, less would have been more.

Much Is Good, More Is Better

A game is more than mechanics. Good mechanics are useless without content to support them, while poor ones can be worked around. Subsystems are only any use if they're referenced, and flaws only become annoyances to the extent the content pushes you into them.

Pillars' content supports the mechanics relatively well. Most spells and special abilities are genuinely useful in combat and there is room for a lot of experimentation with different parties, character builds, and tactics. Outside combat, your choices in character-building and story are acknowledged with unique dialog options or CYOA interactions. The developers have taken care to ensure that all skills get uses, all dispositions and reflected in dialogs, and pumping any attribute gets acknowledged.

Combat encounters are thematically consistent but varied, with lots of different types of enemies with distinct special abilities, coming at you in different combinations and letting you make use of all those spells, specials, and gear you've collected on the way. Even “trash” enemies like xaurips come in a range of flavours: ordinary scrubs, skirmishers with a nasty paralysing attack, harder-hitting champions, and priests bombarding you with area-effect damage. A group of ogres may include druids casting spells that can effectively silence your spellcasters while doing serious amounts of damage over time. Same for oozes of various sizes and colours, incorporeal undead that range from the somewhat annoying shadows to seriously scary totally-not-banshee cêan gŵla. Corporeal undead — “vessels” in Pillars parlance — show up in groups which include archers, melee combatants, casters, and fampyrs which not only regenerate fast but are able to charm party members. There are a couple of areas with rather a lot of similar enemies — a lord’s castle has lots of guards, a cultists’ secret temple has lots of cultists — but they’re relatively infrequent, and in those cases the obvious quest solution is usually to not fight them all.

Yet there are missed opportunities as well. Some of the most memorable encounters in Baldur’s Gate 2 featured the environment as much as the monsters. Sadly, Pillars has no counterpart for Firkraag’s dungeon with its flanking orc archers, close-quarters ambushes, or wolfweres luring the hapless party into a trap, despite the beautiful possibilities offered by the Engwithan ruins where much of the action takes place. The best we get is a couple of fights in areas with some traps scattered around, which we can’t disarm during combat, presumably due to the “game state” implementation of stealth.

Fights between adventuring parties are underwhelming, especially on difficulties below Path of the Damned. These are among the toughest and most varied in Baldur's Gate 2, but in Pillars, with a couple of notable exceptions in the first act when they're between low-level parties, they're too easy. This is largely due to deficiencies in the AI: enemy parties don't manage to support each other with their abilities as efficiently as they should, and it’s easy to take out the crucial spellcasters early on.

On the whole, the game’s encounter variety is let down by its difficulty level. At difficulties up to Hard they just don’t push you past the point of discovering a few standard tactics that work well enough, and it’s easy to get caught in a rut of repeating them until the endgame. There are more efficient — and more fun — ways to play, but you have to dial it up to Path of the Damned to get any push from the game to discover them.

Your Kind's Not Welcome In These Parts

Instead of a D&D alignment, Pillars tracks your reputation with various factions, and your disposition — what kind of person people think you are. Disposition is extremely important for paladins and priests, as a disposition which aligns with your ethos strengthens your best special abilities. For everyone else, it's mostly flavour: dialog choices that open up, sometimes offering shortcuts, alternative solutions, or information you would otherwise have missed.

Some of the lustre comes off the disposition system if you make the numbers visible and pay close attention to the reputations and dispositions you're acquiring, turning it into a minigame. Playing as a paladin is much more engaging if you have to figure out "blind" how to play to your order's favoured dispositions, rather than just reflexively picking "Diplomatic" and "Honest" whenever they're offered. I tried this a good way into Chapter 2 with a Shieldbearer of St. Elcga, and while I didn’t get a “perfect score,” I did rack up most ranks in the dispositions I was targeting, and none in the ones I was avoiding.

There are also missed opportunities. If you play as a priest of one of the gods figuring in the game's story, your status will be acknowledged every now and then, but relatively superficially. If a plotline throws you into conflict with other priests of the god you serve, you won't be able to side with them from the get-go, and there are occasional silly moments like a priest of Eothas offered a dialog line, “Who’s Eothas?”

The faction reputation system is based on what you do rather than what you say or how you do it. It is a traditional affair, where you gain reputation with a faction by doing stuff for them, and lose it by aligning with an opposing faction, or doing things that go against their interests. This is only really significant in the mid-game, where you can only progress after deciding which Defiance Bay faction to align with. These choices are also let down by a forced plot twist, although their long-term consequences are explored in the endgame slideshow.

The overall effect is nice but fairly subtle. You do feel that the game acknowledges the particular choices and characteristics that make Charname unique, better than in most cRPG's, including the Infinity Engine ones. It makes the world feel alive and that the way you built your character and interact with the world matter. The main narrative, however, is more linear than you might expect, and because of the mixed Disposition you will likely accumulate, your experience in different playthroughs will not change all that much. This is no Fallout: New Vegas, but nor is it an Icewind Dale.

Off The Level

Overall, Pillars is somewhere between the IE games and modern mainstream expectations in difficulty. I was playing Pillars and Baldur's Gate 2 concurrently, spending a few days or a week on one, then the other. I had Pillars on Hard and Baldur's Gate 2 on Core Rules, and the challenge level felt roughly similar; I was winning and losing encounters at about the same frequency, and my "adventuring day" felt about equally long, although Baldur’s Gate 2’s hardest optional encounters were tougher than Pillars’, and permadeath meant a good deal more reloading. On Path of the Damned, the harder encounters were close to Baldur’s Gate 2 hard, especially in the early game.

Difficulty swings somewhat through the game. Parts of Chapter 1 can be punishingly hard if you go after them early, as can be parts of Chapter 3 if you’ve mostly just followed the main quest’s breadcrumb trail. Apart from a few optional encounters, Chapter 2 becomes easy towards the end as you gain levels and items, in whichever order you play it. By modern mainstream standards Pillars is a pretty hard game; by the standards of 15 years ago, or the likes of Blackguards or Dwarf Fortress, it is on the easy side.

The Endless Paths of Od Nua and the bounties on offer at your stronghold — Kickstarter stretch goals, both of them — can make a real mess of the power curve. Do the side content everywhere else, and you will hit the endgame with a couple of party members still hungry for another level. Dive into the megadungeon, and when you come out, you will be outleveled and out-geared for what’s left of the game.

Path of the Incline

Unlike most games these days, difficulty levels up to Hard don’t change the rules or the enemy stats in any way. Instead, you get tougher variants of enemies in bigger groups — adra beetles in addition to stone and wood beetles, shadows upgraded to shades, shades to phantoms, guls to darguls, darguls to fampyrs, and so on. Only the hardest level, billed as a special challenge for the truly hardcore, adjusts the numbers.

That’s a shame, because on Path of the Damned Pillars plays a lot more like it ought to. Status effects start biting. Enemies have hard enough defences that attacking them with the right combinations is often a requirement. They hit hard enough that repeating good-enough tactics won’t always cut it. You start paying serious attention to consumables and crafting. And even so, some of the optional fights are truly punishing, at least if you go into them early.

Pillars suffers from the design decision to produce difficulty levels by changing the encounter composition rather than adjusting the numbers. Casual players who can’t be bothered to learn the mechanics at all will find Easy frustratingly hard, whereas more experienced players will soon snooze through Hard by mechanically applying a good-enough strategy they happened upon. There are more efficient and more fun ways to play, but the game leaves it up to you to discover them.

The game would likely have been received a good deal better among the hardcore crowd if Hard had been more or less like Path of the Damned with, perhaps, the mobs a little smaller, and another, even higher difficulty level above it, or a second difficulty slider tuning the numbers so it would have been possible to play against Hard enemies with Path of the Damned rules. As it is, Path of the Damned is the most enjoyable difficulty level in the game, but it doesn’t live up to its billing as a Heart of Fury spiritual successor.

A Brave New World