- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 100,143

Tags: Chris Avellone; Obsidian Entertainment

There's an interesting new interview with Chris Avellone over at RPGamer. Not so much because it contains any new information, but because of its comprehensiveness. Over two years after his departure from Obsidian, it feels like Chris has his thoughts fully in order about the circumstances that led to that departure, and about what he's looking for now. It's not as abrasive as last year's infamous SugarBombed interview, but in its own way just as brutal. Here's an excerpt:

There's an interesting new interview with Chris Avellone over at RPGamer. Not so much because it contains any new information, but because of its comprehensiveness. Over two years after his departure from Obsidian, it feels like Chris has his thoughts fully in order about the circumstances that led to that departure, and about what he's looking for now. It's not as abrasive as last year's infamous SugarBombed interview, but in its own way just as brutal. Here's an excerpt:

JS: I have read in interviews that it seems one of the reasons you left Obsidian was due to creative differences you had with management. First, is that correct? And if so, has going freelance helped to allowed you the creative freedom you desired?

CA: No, the departure was largely due to organizational and management aspects – not anything to do with the developers and folks who worked on the games. And please don't think this is somehow implying I'm a great manager, I'm not. I don't read tons of management books, I don't hang around with agents and business development reps, and I often feel lost around managers and CEOs because I don’t understand a lot of the jargon. In general, my management approach is more about establishing hierarchy, setting expectations, trusting people with the proper title and roles, giving consistent feedback (esp. positive feedback – which is more important when it isn't accompanied by negative feedback), don't play favorites or hire family/friends, and recognizing that if one doesn't have enough money and one doesn't have enough time to make a good game, figure out (1) how it got to that point so you don't repeat it, and (2) what can be done right now to fix both for the sake of a project – even if it means personal sacrifice of time, and your own funds to make a good game.

In terms of freedom, we did get a chance to work on a range of projects and pursue a few of our own IPs. But obviously, there’s things you are never able to do while full-time at a company, there are people you aren't allowed to work with, people you can no longer work with that got laid off, companies you can't collaborate with (pretty much almost all of them), and franchises you'll never be able to contribute to – including genres you can't contribute to, either, because that's not the studio expectation or specialty. Also, it was rare to have a chance to work with the same company twice (to completion), so it was difficult to build a lasting relationship.

Freelancing doesn't fix all these issues, but it fixes a lot of them — there's much more power over your responsibilities, how much you can affect change, the type of work you can choose and the expectations for that work, and a wide range of people, franchises, and genres you can work with. Not only have I worked on more projects in the last two years since going freelance, but I've learned more than I ever did in the last ten years as well. And even better, companies come back to you for more work because you did a good job for them the first time.

Again, I don't have a personal problem with devs at any place I've worked at – some of them I've worked with for over 15 years, and I remain in contact with many of them and see them frequently (sometimes out in the freelance world as well). I wish them all the best.

JS: Do you have any regrets going solo? Would you be open to joining another studio full-time again?

CA: Family matters preclude me from being able to join a studio full-time (it was much the same thing at the end of Obsidian, which fueled the departure). Although, honestly, while I've worked with a number of studios I admire, I'd rather try my hand at making my own first, although it'd be structured differently than most other game studios.

As for regrets going solo? None. If anything, I work with more people now than I did before, but the structure is clearer (hierarchy, responsibilities, titles, contractual awareness), and I get to choose my work based on what interests me. I'm a little disappointed in myself because I should have done it years ago. I was tempted to do it when I resigned from Black Isle (I got a very brief gig with Snowblind on Champions of Norrath, and that brief glimpse should have been a big neon sign that life's better on the other side).

It's my fault for being afraid, though, I think I had different expectations of what an owner was and also, I was too scared of not having the "standard trappings" of a job without realizing the drawbacks that come with that. In the digital age now, it's even more of a drawback, and I think it's more expensive for companies in the long run.

JS: Have you had a chance to play any of these games yourself? What feedback you would give for elements that could be improved on? What are they doing right?

CA: I've played all the ones you've mentioned, sure. Any challenges Divinity had from the first one are being addressed in the second – and then some (gamemaster mode, party members with conflicting agendas, etc.). Their turn-based combat is smooth, by the way.

I do think the nature of isometric games carries certain challenges in terms of technical improvement, but often, I think more interesting innovations have to come in customization, setting, and systems, both mechanical and narrative – if you’re not doing much new in those departments, then you might want to re-examine your design.

Also, a lot of it is listening to the audience and what they want and ask for rather than dismissing things they want that have been in previous games they enjoyed. Ex: Being able to customize and mod the game as much as possible without roadblocks? Sure. (And developers should support this, as this will add longevity to the game, and see ideas you'd never even realize come to fruition.) Gamemaster mode? Sure. Multiplayer that doesn’t sacrifice the single-player narrative? Sure. Deeper and more integrated companions? Sure. Other aspects are managerial – the content is only part of the equation.

First, one problem ends up being that developers want to make too much content (or make too many promises they can't support financially), without realizing what that extra content does to the fun and quality of a game. I've been guilty of this, for certain, so please don't think I'm claiming otherwise. To this day, I still have to remind myself that, "I'm a game developer, I will always make games, and that means, I can still 'cut' things and they won't be lost – they're there for the next game, but let's focus on making this game fun." The problem can also come when developers cling too tightly to an aspect of a game, and even when the signs are on the wall that it's very unlikely to get done, they still hold on to it, or still want to discuss it, even though it becomes more impractical by the day.

The second challenge is managing that content – and that means editing, subtracting, and making game spaces and gameplay systems more convenient to play rather than filled with arbitrary filler and challenges – even game systems need an editor (a content editor, not a toolset, although a good toolset helps, too). Also, in terms of management, is the ability to recognize when there's too much content, or if the nature of a developer's "fix" to get something perfect is really the province of that department, or if it's something that can easily be fixed with story and lore. It's a little hard to explain, but I am genuinely one of those people who believe that the writer can fix this; we can. But, we might need some time and trust.

JS: Can you share what you are working on currently, or any future projects you will be attached to in the future?

CA: A lot were mentioned already in the opening, and the others I can't talk about yet to keep the secrets (even though I REALLY WANT TO). Keep the eye on the horizon, as I can guarantee that at least one of them in particular, people are going to be pleasantly surprised (probably more about the title than my presence), and it's definitely something that wouldn't have been possible if I was full-time at a company.

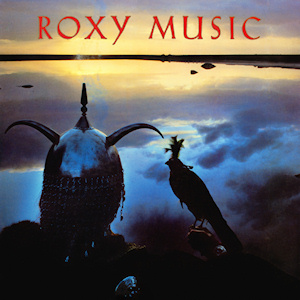

Hmmm, I wonder what he's talking about at the end there. Could it have something to do with this?CA: No, the departure was largely due to organizational and management aspects – not anything to do with the developers and folks who worked on the games. And please don't think this is somehow implying I'm a great manager, I'm not. I don't read tons of management books, I don't hang around with agents and business development reps, and I often feel lost around managers and CEOs because I don’t understand a lot of the jargon. In general, my management approach is more about establishing hierarchy, setting expectations, trusting people with the proper title and roles, giving consistent feedback (esp. positive feedback – which is more important when it isn't accompanied by negative feedback), don't play favorites or hire family/friends, and recognizing that if one doesn't have enough money and one doesn't have enough time to make a good game, figure out (1) how it got to that point so you don't repeat it, and (2) what can be done right now to fix both for the sake of a project – even if it means personal sacrifice of time, and your own funds to make a good game.

In terms of freedom, we did get a chance to work on a range of projects and pursue a few of our own IPs. But obviously, there’s things you are never able to do while full-time at a company, there are people you aren't allowed to work with, people you can no longer work with that got laid off, companies you can't collaborate with (pretty much almost all of them), and franchises you'll never be able to contribute to – including genres you can't contribute to, either, because that's not the studio expectation or specialty. Also, it was rare to have a chance to work with the same company twice (to completion), so it was difficult to build a lasting relationship.

Freelancing doesn't fix all these issues, but it fixes a lot of them — there's much more power over your responsibilities, how much you can affect change, the type of work you can choose and the expectations for that work, and a wide range of people, franchises, and genres you can work with. Not only have I worked on more projects in the last two years since going freelance, but I've learned more than I ever did in the last ten years as well. And even better, companies come back to you for more work because you did a good job for them the first time.

Again, I don't have a personal problem with devs at any place I've worked at – some of them I've worked with for over 15 years, and I remain in contact with many of them and see them frequently (sometimes out in the freelance world as well). I wish them all the best.

JS: Do you have any regrets going solo? Would you be open to joining another studio full-time again?

CA: Family matters preclude me from being able to join a studio full-time (it was much the same thing at the end of Obsidian, which fueled the departure). Although, honestly, while I've worked with a number of studios I admire, I'd rather try my hand at making my own first, although it'd be structured differently than most other game studios.

As for regrets going solo? None. If anything, I work with more people now than I did before, but the structure is clearer (hierarchy, responsibilities, titles, contractual awareness), and I get to choose my work based on what interests me. I'm a little disappointed in myself because I should have done it years ago. I was tempted to do it when I resigned from Black Isle (I got a very brief gig with Snowblind on Champions of Norrath, and that brief glimpse should have been a big neon sign that life's better on the other side).

It's my fault for being afraid, though, I think I had different expectations of what an owner was and also, I was too scared of not having the "standard trappings" of a job without realizing the drawbacks that come with that. In the digital age now, it's even more of a drawback, and I think it's more expensive for companies in the long run.

JS: Have you had a chance to play any of these games yourself? What feedback you would give for elements that could be improved on? What are they doing right?

CA: I've played all the ones you've mentioned, sure. Any challenges Divinity had from the first one are being addressed in the second – and then some (gamemaster mode, party members with conflicting agendas, etc.). Their turn-based combat is smooth, by the way.

I do think the nature of isometric games carries certain challenges in terms of technical improvement, but often, I think more interesting innovations have to come in customization, setting, and systems, both mechanical and narrative – if you’re not doing much new in those departments, then you might want to re-examine your design.

Also, a lot of it is listening to the audience and what they want and ask for rather than dismissing things they want that have been in previous games they enjoyed. Ex: Being able to customize and mod the game as much as possible without roadblocks? Sure. (And developers should support this, as this will add longevity to the game, and see ideas you'd never even realize come to fruition.) Gamemaster mode? Sure. Multiplayer that doesn’t sacrifice the single-player narrative? Sure. Deeper and more integrated companions? Sure. Other aspects are managerial – the content is only part of the equation.

First, one problem ends up being that developers want to make too much content (or make too many promises they can't support financially), without realizing what that extra content does to the fun and quality of a game. I've been guilty of this, for certain, so please don't think I'm claiming otherwise. To this day, I still have to remind myself that, "I'm a game developer, I will always make games, and that means, I can still 'cut' things and they won't be lost – they're there for the next game, but let's focus on making this game fun." The problem can also come when developers cling too tightly to an aspect of a game, and even when the signs are on the wall that it's very unlikely to get done, they still hold on to it, or still want to discuss it, even though it becomes more impractical by the day.

The second challenge is managing that content – and that means editing, subtracting, and making game spaces and gameplay systems more convenient to play rather than filled with arbitrary filler and challenges – even game systems need an editor (a content editor, not a toolset, although a good toolset helps, too). Also, in terms of management, is the ability to recognize when there's too much content, or if the nature of a developer's "fix" to get something perfect is really the province of that department, or if it's something that can easily be fixed with story and lore. It's a little hard to explain, but I am genuinely one of those people who believe that the writer can fix this; we can. But, we might need some time and trust.

JS: Can you share what you are working on currently, or any future projects you will be attached to in the future?

CA: A lot were mentioned already in the opening, and the others I can't talk about yet to keep the secrets (even though I REALLY WANT TO). Keep the eye on the horizon, as I can guarantee that at least one of them in particular, people are going to be pleasantly surprised (probably more about the title than my presence), and it's definitely something that wouldn't have been possible if I was full-time at a company.

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)

![Glory to Codexia! [2012] Codex 2012](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_slushfund2012.png)