Steve Barcia started thinking about his second grand-strategy game well before he had finished creating his first one. While he was waiting for his latest iteration of Master of Orion to compile each day in the cramped Austin, Texas, offices of his company SimTex, he sketched in the mental details of a follow-up that would take place in a fantasy rather than science-fictional milieu. As soon as the one game was finished, he wrote up a design document for the next one and shared it with the rest of the SimTex staff. Within two weeks, they were charging full-speed ahead on Master of Magic. It would ship under the MicroProse imprint in time for the Christmas of 1994, only a year after its predecessor, despite being one of the most complex strategy games yet made for a computer. If there’s no rest for the wicked, it would seem that Barcia and company had been very bad indeed.

Given the new game’s title and its short development cycle, one might suspect it to be little more than a reskinned Master of Orion. In reality, though, such could hardly be further from the truth. Master of Magic is a wildly different experience from Master of Orion, enough so that one would scarcely guess it to have come from the same designer. Where Master of Orion is polished to perfection, its every element carefully considered and tested, Master of Magic is a far more ramshackle affair, a pile of diverse ideas thrown together — some more fully realized than others, some literally not working at all if we want to get pedantic about it. Nevertheless, it all comes out okay in the end; the game’s variety, generosity, and sheer chutzpah win through. Master of Magic is simply fun — every bit as much fun as Master of Orion. Just don’t try this at home, budding designers.

...

This, then, is one important aspect of

Master of Magic. You start with a single village which you must grow and develop. Meanwhile you send out settlers to found other cities, or armies to conquer ones that already exist. You improve your cities by ordering their populations to build structures that increase their production or otherwise cause them to function more efficiently. All of this will be very familiar indeed to any

Civilization veteran. That said, the city-building side of

Master of Magic is generally simplified in comparison to

Civilization. There is, for example, no tech tree to research in order to unlock new types of buildings. Instead buildings themselves unlock other buildings, as shown by a handy chart included in the manual: constructing a builder’s hall unlocks the granary, shrine, library, miner’s guild, and city walls; constructing a granary unlocks the farmer’s market; etc., etc. Steve Barcia, who was eager for understandable reasons to ensure that the similarities to

Civilization weren’t overstated, explained the simplifications by noting that the two games had fundamentally different design goals: “

Civilization focuses on internal problems. In

Master of Magic, it’s the external; it’s conquest.”

...

In the context of its own day,

Master of Magic thus joined Julian Gollop’s

X-COM, which was released about six months before it, as one of the foremost exemplars of a new trend in strategy games, that of using CRPG elements to forge a more personal, even emotional bond between the player and the figures she commands. It works brilliantly here, just as it does in

X-COM. You come to identify deeply with your units and especially your heroes as you nurture their development, and come to mourn the loss of one of them almost like that of a real friend.

The debt which

Master of Magic owes to the CRPG genre extends to other areas as well. Its randomly generated maps are seeded not just with neutral and enemy towns but with “fallen temples,” “abandoned keeps,” and “mysterious caves.” You can send your units and heroes to confront what is found within, if you dare; your reward for doing so is booty and the experience they earn, assuming they survive. Just exploring the world, revealing and clearing out more and more of the map, is thoroughly enjoyable even before you meet any of the computer players who are doing the same thing.

...

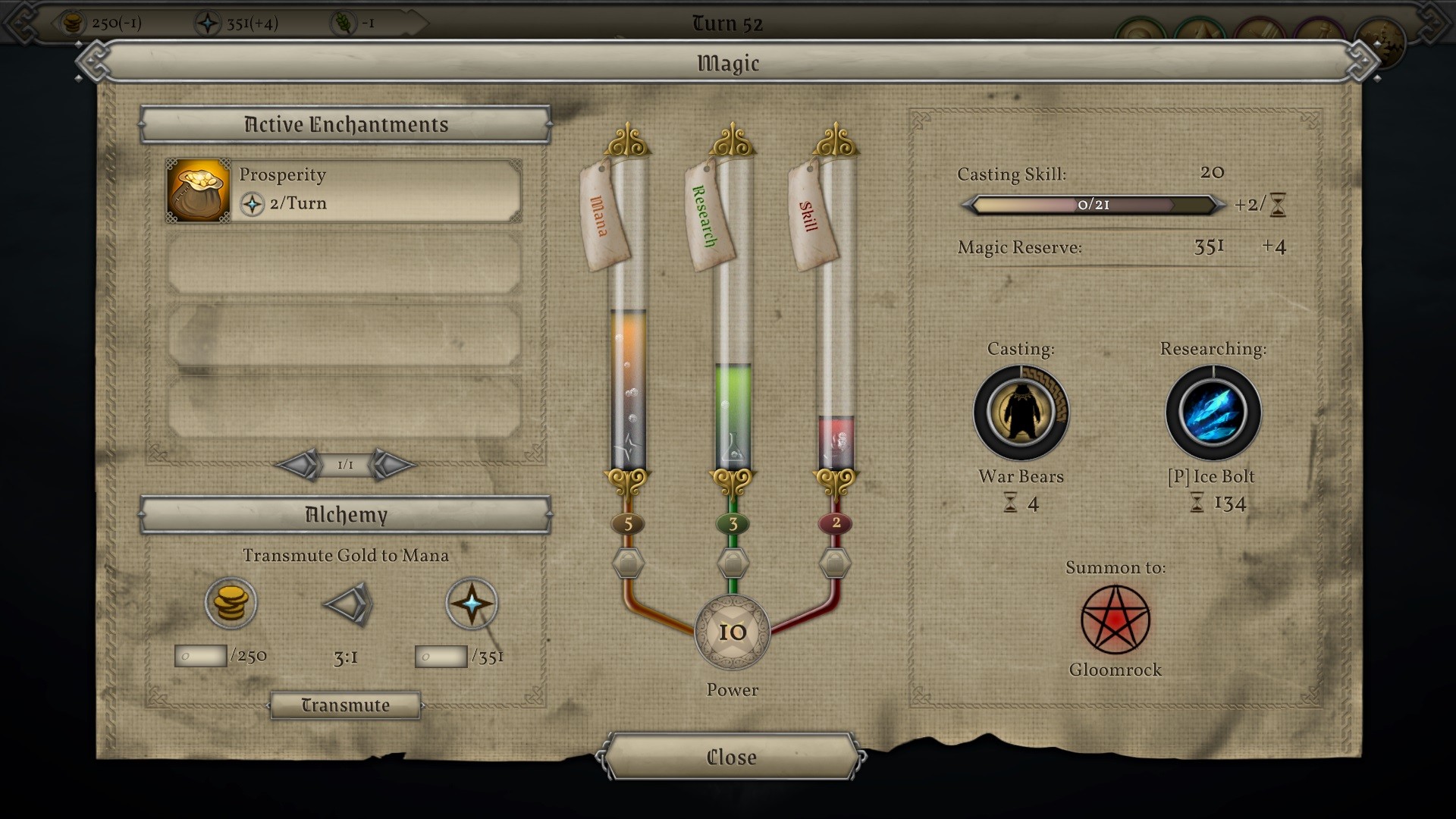

The thoroughgoing watchword of

Master of Magic is variety, applying not only to the list of spells but to every aspect of the game. The sheer amount of

stuff here would be impressive in a modern game, and was well-nigh unprecedented at the time of this one’s release. In addition to choosing one of fourteen starting wizards, you choose a starting race for her to command from another fourteen possibilities; each of these races comes with its own unique set of units to be unlocked and raised, as well as a unique mix of buildings that it can erect in its towns. You can choose a world with small, medium, or large land masses, with weak, normal or powerful magic. All these possible starting parameters alone ensure that the game will take a long time indeed to get old. Then, once you actually begin to play, you find an absurdly wide array of monsters to contend with, heroes to recruit, and magical arms and armor to dredge up. And then there are all those spells: spells to buff your units and heroes and to nerf your enemies’, to summon fantastical creatures to join your ranks, to disrupt your foes’ own magic. Eventually your powers become downright Biblical, as you control the winds and blight your enemies’ fields and forests — but be aware that they can potentially do the same things to you. By way of a final touch, you have not one but two complete worlds to explore and conquer; there are two separate dimensions in the game, the relatively mundane Arcanus and the magic-rich realm of Myrror. You can move between them by means of special portals on the landscape which you must discover and secure — or, inevitably, via yet another spell you can research. It will take you a long, long time to see everything that

Master of Magic has to offer.

...

Although its overall reception was gravely impacted by its unconscionable state at the time of its release, a small group of players fell in love with the game for its crazy multitudinousness and kept its memory alive for years, then decades. They did so not least because

Master of Magic became the opposite of

Master of Orion in one final, supremely ironic way: whereas

Master of Orion spawned about a thousand 4X rule-the-galaxy copycats of varying degrees of quality, nobody else has ever done a game quite like

Master of Magic. The year after it appeared, New World Computing released

Heroes of Might and Magic, a superficially similar blending of strategy and CRPG elements, but one that was dramatically different in the details: it was a more tightly focused effort, with pre-crafted maps in place of randomly generated worlds, a modest but carefully tuned suite of spells and creatures in place of a decadent cornucopia of same, and a multi-mission story-oriented campaign in place of a wide-open sandbox to play in. When

Heroes of Might and Magic — admittedly, a superb game in its own right — became the hit that

Master of Magic had not, it became the model for fantasy strategy games going forward.

So,

Master of Magic remains a unique experience to this day. While it’s definitely no paragon of balanced game design, its rambunctious riot of possibility ensures that it stays interesting over the long term; this is one quality that it certainly does share with

Master of Orion. In fact, I like to play

Master of Magic just like I play that game: I throw the dice to set up the parameters of my world, my wizard, and my minions, and then have at it, assured that, whatever awaits me, it will be completely different from the last time I played. That’s the kind of variety that can keep you playing a game forever.