Harvest Hulls

Peter Peter pumpkin eater,

Had a wife but couldn’t keep her.

He put her in a pumpkin shell,

And there he kept her very well.

Getting into the thing was harder than she would have imagined. It wasn’t the first time she’d asked herself, how does one climb into a pumpkin shell? Beside her, their makeshift canoe rocked from side to side like a cradle in the water, like some delicate thing not built for two. The hollowed out rind now floated like driftwood despite its bulk and weight. Was floating because they’d wished it to. Because they’d made it so they could ride it together.

Jayne, the pumpkin eater’s wife, wriggled numbing toes in the reedy mud of the bank, watched the waxing glimpse of them, pale as the underbelly of a fish.

She turned to Peter.

“Hold the oars,” by which she meant, hold my oar, because he was already holding the other. (They’d thought to rig a rudder but that hadn’t turned out so well so they were going to have to steer with the paddles.) Then, nimbly, she gathered her skirts and eased into the round pumpkin boat. The inside was cushiony and sherbet-soft, a bit soggy where her knees pressed into the pulpy floor, but it held against her weight.

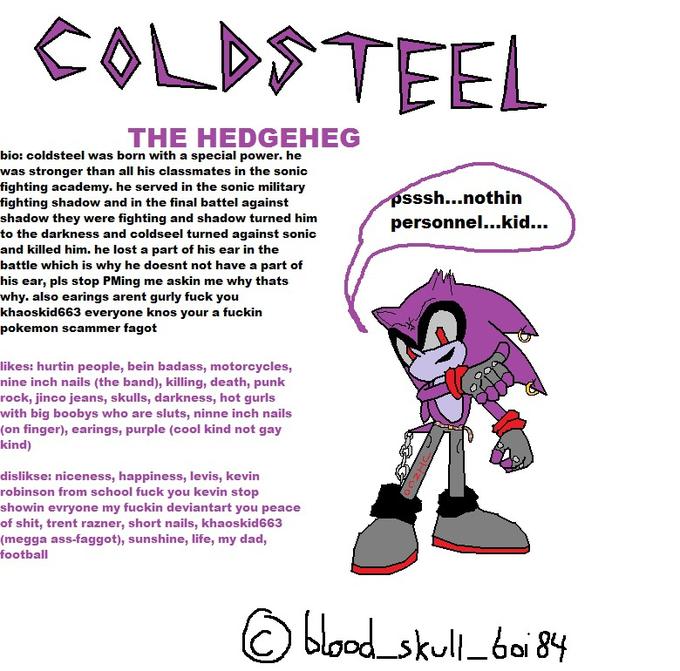

Further out, other contestants of the annual Halloween river regatta bobbed on tiny waves like scattered apples in a water barrel waiting to be plucked, waiting to begin. Giant, 500-pound pumpkins teetered and toddled in all varieties of color and design—zebra striped pumpkins, polka dotted pumpkins, Burberry pumpkins, the eery half-submerged sneers of jack-o-lantern faces. There were some with numbers slopped on the side, bright red race car pumpkins.

There were round, apple bottomed, and lopsided pumpkins, the latter of which had trouble floating upright. There were rotten pumpkins which had never made it into the water and already sunken pumpkins—several contestants had toppled pre-race, disqualifying, their pumpkins upturned and disappeared.

And within the pumpkin boats, the array of mariners wore elaborate or tacky costumes, all the usual: Frankenstein’s monster and naughty nurses, a group of Mario Kart racers, some broomless witches. A skeleton with bone white, incandescent sculls. In one crouched a wooly gorilla, his black, nubby fingers gripping the carved lip of his craft.

And then there was them: a princess and a pumpkin eater, one of the few pairs.

Behind her, Peter looked on nervously. He spoke low, more to himself as if in self-confirmation. “This is what we wanted.”

“We don’t have time to hesitate,” she said, turning. “They’re going to signal soon.”

“I’m not the one who had to stop for Belgian waffles at 4 a.m.” He picked up his knees as he waded, sloshing up to the boat with an unhappiness. His eggshell knee socks yellowed in whole splotches from the cold water.

“I thought it would be fun to get breakfast in costume. It was fun wasn’t it? Hey, no shoes in the boat; I told you.”

Peter pried his shoes from his feet, tucking the pair of loafers under one arm to prevent the heels from etching up the soft inside of the rind.

They’d pulled off the interstate and into the near abandoned parking lot of a mom and pop diner with a burnt out sign that read ‘Mel’s, cinnamon raisin buns no smoking 10 to 2 a.m.’ In the bathroom, after ordering, she peeled into the black and gray shorty wetsuit and then layered it with her Cinderella dress, long white gloves and a set of pearls which had belonged to her mother. The blond, updo styled wig was a more difficult maneuver, and by the time she’d returned to the table his eggs had grown cold. They wobbled, big yolks threatening to spill over where he’d prodded at them with his fork for the rest of the meal.

Peter held his arm out to his wife for a hoist, but she took the oars instead, prying them into jutting angles in the riverbank to steady their position. They nearly both spilled out as he scrambled and settled in.

The fit was tight, snug, she thought, side pressed to his. Her dress crinkled when they moved, the fabric stiff and reminiscent of crinoline. She used the oars to shove off, the two of them shakily gliding out toward the center of the starting line as marked by orange and white buoys.

They waited.

“Tell me you’re having fun,” she sighed, weary and dreamy and shivering.

“You know I’m doing this for you.”

The start gun fired, and she looked away. A spindly old man, the previous four years’ winner, shot forward into the lead, weaving with the water. He was a true pumpkin regatta artist, sculpting with his double-sided blade.

Unlike most everyone else, he wore only an old-timey, full-bodied, striped swimsuit and a navy life jacket, all business. White, flaccid skin twitched against the October air. Maybe the swimsuit was his costume, but Peter’s wife imagined he’d pulled it out of a box in the corner of the attic amidst musky army uniforms and the forgotten years of his life—primary school report cards, a brunette lock of hair, the crumbled green plaster cast of a child’s first hand print.

She’d seen pictures of him wearing his four golden medals in the local newspaper, grinning, close-lipped so as to hide his teeth. Right then and there she’d wanted to take the old coot down.

Unfortunately, the seasoned winner had a couple key things going for him:

- He wasn’t a natural, but he didn’t have to be. He had his technique down. You could see it in the way his arms bunched like there was actually some muscle under all those wrinkles, the way his oar seemed only to skim the surface. Effortless. They weren’t powerful strokes, but they were efficient, and the water loved him.

- He probably weighed less than 90 pounds.

- He had a reputation to uphold, a title to defend, and it was obvious he was going to fight tooth and nail to knock down anyone who got in his path.

A man with a small child perched on his shoulder had told the news crews earlier that morning, “We just want to finish the race.”

But the pumpkin eater’s wife wanted more. Her oar dipped down into the blue water, a clean sweep. She was ready to fly.

§

They used to have fun together. For six weeks they shared this little one bedroom, one-and-a-half-bath flat up in Waterville, Maine. They’d both just finished college a few years before and were working low-status, going-nowhere administrative jobs. It wasn’t that they weren’t career oriented. They just didn’t want to move away.

The place was cozy. It was their spot.

They used to eat spaghetti in bed together. It was the only decent meal Jayne could cook back then, before she became his wife, and so they ate three, sometimes four, nights a week, fingers slick with the meaty red sauce.

The second week they were together, Jayne bought a set of plastic wine glasses from the local home goods store—the glasses were huge, goblets more like, with little marigolds on them, and they used to drink them brimming with three-dollar red wine. It seemed romantic to her at the time, magical.

Then some nights Peter would suckle Jayne’s fingers, meticulously cleaning each one, and she would try to smear sauce or a noodle somewhere along his body first. A nipple, a rib, the inside of his left wrist. Once a dab to the bottom of his earlobe. It was a silly naked game that often led to silly naked sex which wasn’t all that great on an overly full stomach but was fun anyway. Peter had a thing with food and she just liked the pretend spontaneity of it all, the recklessness. Sometimes (and that was the best part) they ended up in the plates of greasy noodles, an elbow or a knee, knocked one of the glasses.

They didn’t care that the sheets were stained.

Then they grew tired of spaghetti. They grew tired of the place and wanted something bigger. They wanted a washing machine, a dryer. A backyard with large oak trees. Then they switched plastic out for crystal, flannel for white linen as maturing couples did (so she’d thought). But they still wanted.

§

A woman with 80s spiked hair in a bowed watermelon was coming up on their rear to the right. She was spitting shiny black seeds at nearby contestants, and worse, passing them.

“Stop her,” Jayne hissed, rowing furiously, twisting wood against water.

“How?”

“Throw a shoe at her.”

“You mean bean her or are we trying to lighten the ship?”

Peter’s humor was lost on her in the heat of the moment. Jayne threw the shoe for him, but the watermelon craft was already past. They watched as the black penny loafer sank to the dark depths.

“I had a hard time finding those,” Peter said.

“Just concentrate on pulling your weight. Please.”

Peter nodded, powder from his colonial wig sprinkling the brown leather of his vested shoulders. “We can win this.” He set his jaw, eyes locked on the finish line or maybe just the bobbing horizon with it’s hazy morning half sun. “I’m sure we can.”

His first real strokes were overpowering and nearly sent them into a skittering spin. His determination was too quick and raw and held too much gusto, held all of himself; she couldn’t keep up with his pace. They needed to find a rhythm, floundering in place. So he started to indicate, “Row. Row. We can go, go.”

§

During their second year together in the new place, Jayne had painted the spare room alternating stripes of Robin’s Egg blue, Chocolate, and Topiary Tint, a gentle shade of green, because she’d had a series of dreams in which she’d borne twins (though they were always impossibly tiny, ruddy, mewling things). Surely, that must be a good sign, she’d thought. It had been so many years now, and she was ready for that next step.

She spent long hours poring through internet baby name origin sites, learned the importance of considering syllabic harmony between first and middle names. She decided if the baby was a girl she’d name her Sweet Pea and if it turned out to be a boy, well, then he’d just have to name himself.

Then they bought a German engineered minivan. They rode around it in to do ‘together’ things while she waited for the good news to come.

Then a couple more years passed.

§

Jayne heard about the Potomac pumpkin regatta through a newspaper clipping in her elderly neighbor’s grandchildren’s holiday scrapbook. Then all she’d had to do was buy Howard Dill’s patented Atlantic Giant seeds—they would plant them in the backyard—and register their number. There was a non-refundable entry fee, so they would have to make sure their pumpkin bloomed to full girth on the first go. There would be no time for second chances.

It was going to be their last hurrah and perfect.

They planted in late May and watched their seedlings grow.

§

By this point it was clear they were taking on water. Her knees were numbing where the short-legged wetsuit failed to insulate them. Soon her shins would feel like knives beneath her skin.

“Peter, it’s cold,” she said.

He said, “Row. Row. Row,” and kept his gaze straight ahead.

With each clipped command Peter cut the river with the head of the oar, his voice the regular tick of a metronome. They would finish this race or drown trying.

But she was tired of trying. They were going nowhere. She was tired of the lack of romance and the same old, same old of familiarity.

She didn’t understand how others seemed to propel forward effortlessly, gliding through the water as if riding the backs of giant swans while they, themselves, only managed to bob from side to side, the pulpy, pale orange rim of their boat dipping beneath the dark surface of the river a millimeter more at a time.

Her costume was soggy and sticking between her legs, the periwinkle ball gown surely ruined. On one row, she let her paddle slip from gloved fingers. There was something she hadn’t told him before, something she could never tell him now. It was during a time when she’d sneaked out alone—those nights she liked to ease barefoot through the pumpkin patch while he was dreaming, drape herself across the giant gourde and stroke its rotund girth like a pregnant belly. But that night she’d noticed an ugly blemish in the rind, one which hadn’t been there before. A porcupine had gnawed along the underside, leaving a nasty flesh wound. She’d been quick to fix it, desperate to hide it away, the next day suggesting they not wait to decorate the thing, and they spent hours debating potential paint jobs. She was keen to paint it to look like a pumpkin, all they needed was a prettier, deeper orange like Circus Peanut or Mandarin Mousse, she explained, but he was under the impression they needed some sort of pattern or number on the side lest they look like amateurs.

“This isn’t a god damned box car,” she’d said. “It’s a chariot.” In the end the patch had simply been slathered over, unnoticed and forgotten.

It was evident her handiwork had failed—there was nothing holding them together now.

“Abandon ship,” she yelped, spilling over the brim.

Under the water her dress became a tangled weight and she ended up kicking against more fabric than river. The summer wetsuit beneath that did little to warm her.

How Peter had managed not to also capsize was beyond her, but he was still there stroking from side to side when she came up, teeth chattering. Staring at the broad line of his shoulders, she realized he was slowly moving away from her. Without her weight he was finally making progress, falling into a rhythm. Leaving her behind.

She thought about how she’d always imagined he’d propose to her under the weight of so much water, on a scuba diving trip in the Caribbean. That amidst the coral reefs and the schools of striped damselfish, he’d dig around a corner of the ocean floor (their corner) searching for some long forgotten treasure beneath sand and shells. Then, of course, he’d motion her over with excitement, and digging now herself, she’d unearth the tiny box hidden within his hand. Opening it she’d express her jubilation with an excess of air bubbles, miming her acceptance through the universal thumbs-up sign, much to his relief.

Then they could be happy forever. Would have been, if it had happened that way. With the thumbs-up and the digging and maybe even an awkward underwater hug. But now the river was calling for her alone, dragging her down by her heels and pressing her down by her shoulders. And the air bubbles which scattered up to the surface looked glassy and sad. Like loosed balloons, regrettable.

When she swam for the shore, snaking out of the heavy dress to let it sink to the depths, each intake of breath felt like the rising sun, a slow burning in her lungs, the morning’s waffles a painful stitch in her ribs. In the distance, her pumpkin eater rowed onward in their sinking ship, paddle scooping rhythmically against the river, face outstretched toward the finish line, determined to make it work until the end.

.

![Glory to Codexia! [2012] Codex 2012](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_slushfund2012.png)