But now, at last, Simon & Schuster had the mandate to move in the other direction, to create a

game more consonant with what the

show had been. In that spirit they secured the services of

Diane Duane, an up-and-coming science-fiction and fantasy writer who had two

Star Trek novels already in Pocket’s publication pipeline, to write a script for a

Star Trek adventure game. Duane began making notes for an idea that riffed on the supposedly no-win

Kobayashi Maru training scenario that had been

memorably introduced at the beginning of the movie

Star Trek II. The game’s fiction would have you participating in an alternative, hopefully more winnable test being considered as a replacement. Thus you would literally be playing

The Kobayashi Alternative, the goal of which would be to find Mr. Sulu (

Star Trek: The Search for Sulu?), now elevated to command of the

USS Heinlein, who has disappeared along with his ship in a relatively unexplored sector of the galaxy.

Simon & Schuster’s first choice to implement this idea was the current darling of the industry, Infocom. As we’ve already learned in

another article, Simon & Schuster spent a year earnestly trying to buy Infocom outright beginning in late 1983, dangling before their board the chance to work with a list of properties headed by

Star Trek. An Infocom-helmed

Star Trek adventure, written by Diane Duane, is today tempting ground indeed for dreams and speculation. However, that’s all it would become. Al Vezza and the rest of Infocom’s management stalled and dithered and ultimately rejected the Simon & Schuster bid for fear of losing creative control and, most significantly, because Simon & Schuster was utterly disinterested in Infocom’s aspirations to become a major developer of business software. As Infocom continued to drag their feet, Simon & Schuster made the fateful decision to take more direct control of Duane’s adventure game, publishing it under their own new “Computer Software Division” imprint.

Development of The

Kobayashi Alternative was turned over to a new company called Micromosaics, founded by a veteran of the Children’s Television Workshop named Lary Rosenblatt to be a sort of full-service experience architect for the home-computer revolution, developing not only software but also the packaging, the manuals, and sometimes even the advertising that accompanied it; their staff included at least as many graphic designers as programmers. The packaging they came up with for

The Kobayashi Alternative was indeed a stand-out even in this era of oft-grandiose packaging. Its centerpiece was a glossy full-color faux-Star Fleet briefing manual full of background information about the

Enterprise and its crew and enough original art to set any Trekkie’s heart aflutter (one of these pictures, the first in this article, I cheerfully stole out of, er, a selfless conviction that it deserves to be seen). Sadly, the packaging also promised light years more than the actual contents of the disk delivered.

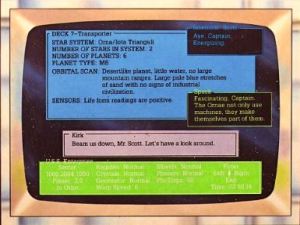

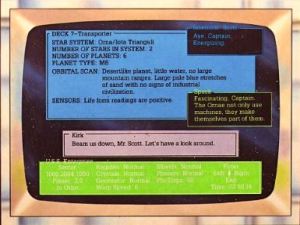

This alleged screenshot from the back of

The Kobayashi Alternative‘s box is one of the most blatant instances of false advertising of 1980s gaming.

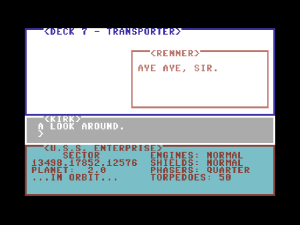

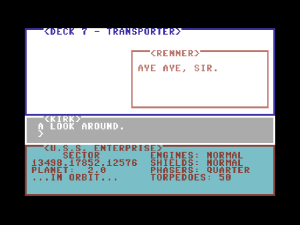

What the game actually looks like…

Whatever else you can say about it, you can’t say that

The Kobayashi Alternative played it safe. Easily dismissed at a glance as just another text adventure, it’s actually a bizarrely original mutant creation, not quite like any other game I’ve ever seen. Everything that you as Captain Kirk can actually do yourself — “give,” “take,” “use,” “shoot,” etc. — you accomplish not through the parser but by tapping function-key combinations. You move about the

Enterprise or planetside using the arrow keys. The parser, meanwhile, is literally your mouth; those things you type are things that you

say aloud. This being

Star Trek and you being Captain Kirk, that generally means orders that you issue to the rest of your familiar crew. And then, not satisfied with giving you just an adventure game with a very odd interface, Micromosaics also tried to build in a full simulation of the

Enterprise for you to logistically manage and command in combat. Oh, and the whole thing is running in real time. If ever a game justified use of the “reach exceeded its grasp” reviewer’s cliché, it’s this one.

The Kobayashi Alternative is unplayable. No one at Microsmosaics had any real practical experience making computer games, and it shows.

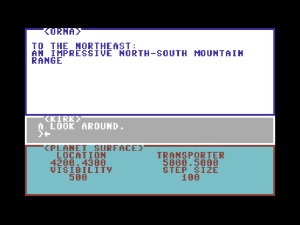

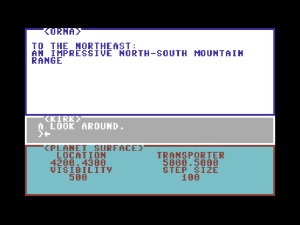

A strange new world with a notable lack of new life and new civilizations

The Kobayashi Alternative is yet another contender for the title of emptiest adventure game ever. In fact, it takes that crown handily from the likes of Level 9’s

Snowball and Electronic Arts’s

Amnesia. In lieu of discrete, unique locations, each of the ten planets you can beam down to consists of a vast X-Y grid of numerical coordinates to dully trudge across looking for the two or three places that actually contain something of interest. Sometimes you get clues in the form of coordinates to visit, but at other times the game seems to expect you to just lawnmower through hundreds of locations until you find something. The

Enterprise, all 23 decks of it, is implemented in a similar lack of detail. It turns out that all those empty, anonymous corridors we were always seeing in the television show really were almost all there was to the ship. When you do find something or somebody, the parser is so limited that you never have any confidence in the conversations that result. Some versions of the game, for instance, don’t even understand the word “Sulu,” making the most natural question to ask anyone you meet — “Where is Sulu?” — a nonstarter. And then there are the bugs. Crewmen — but not you — can beam down to poisonous planets in their shirt sleeves and remain unharmed; when walking east on planets the program fails to warn you about dangerous terrain ahead, meaning you can tumble into a lake of liquid nitrogen without ever being told about it; crewmen inexplicably root themselves to the ground planetside, refusing to follow you no matter how you push or cajole or even start shooting at them with your phaser.

Following

The Kobayashi Alternative‘s 1985 release, gamers, downright desperate as they were to play in this beloved universe, proved remarkably patient, while Simon & Schuster also seemed admirably determined to stay the course. Some six months after the initial release they published a revised version that, they claimed, fixed all of the bugs. The other, more deep-rooted design problems they tried to ret-con with a revised manual, which rather passive-aggressively announced that “

The Kobayashi Alternative differs in several important ways from other interactive text simulations that you may have used,” including being “completely open-ended.” (Don’t cry to us if this doesn’t play like one of Infocom’s!) The parser problems were neatly sidestepped by printing every single phrase the parser could understand in the manual. And the most obvious major design flaw was similarly addressed by simply printing a list of all the important coordinates on all of the planets in the manual.

Interest in the game remained so high that

Computer Gaming World‘s Scorpia, one of the premier fan voices in adventure gaming, printed a second multi-page review of the revised version to join her original, a level of commitment I don’t believe she ever showed to any other game. Alas, even after giving it the benefit of every doubt she couldn’t say the second version was any better than the original. It was actually worse: in fixing some bugs, Micromosaics introduced many others, including one that stole critical items silently from your inventory and made the game as unsolvable as the no-win scenario that provided its name. Micromosaics and Simon & Schuster couldn’t seem to get

anything right; even some of the planet coordinates printed in the revised manual were wrong, sending you beaming down into the middle of a helium sea. Thus Scorpia’s second review was, like the first, largely a list of deadly bugs and ways to work around them. The whole sad chronicle adds up to the most hideously botched major adventure-game release of the 1980s, a betrayal of consumer trust worthy of a law suit. This software thing wasn’t turning out to be quite as easy as Simon & Schuster had thought it would be.

Better than these

Better than these

![Have Many Potato [2013] Codex 2013](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_potato2013.png)

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)