The problems began to crop up on several separate fronts soon after the new year of 1995. Heitman could be abrasive; Corey liked to say that “some people do not suffer fools gladly, but Bob Heitman doesn’t suffer them at all.” Bob Bates, whom Heitman may or may not have considered a fool, was unimpressed with his counterpart’s shoot-from-the-hip way of running his development studio. Following a visit to Oakhurst in February, his assessment of Triton’s performance was not good:

1) No one is really taking charge of project management.

2) The animation requirement is up to 60 man-weeks, and they haven’t been able to hire any artists yet.

3) One background artist we supplied simply isn’t producing.

4) They’re not segmenting text from code, so there’s a big localization problem coming.

5) Internal personality problems are plaguing the team.

Bob Bates was also worried that Triton might use the software technology Legend was sharing with them in other companies’ projects, and almost equally worried that other companies’ code might sneak into

Shannara with potential legal repercussions, given the chaos that reigned in their offices.

With tempers flaring, the Coles stepped in to try to calm the waters. They formed their own company, which they called FAR Productions, after Flying Aardvark Ranch, their nickname for their house in Oakhurst. Officially, FAR took over responsibility for the project, but the arrangement was something of a polite fiction in reality: FAR leased office space from Triton and continued to work with largely the same team of people. Nevertheless, the arrangement did serve to paper over the worst of the conflicts.

Meanwhile Bob Bates had other issues with the Coles themselves — issues which had less to do with questions of competence or even personality and more to do with design philosophy. The Coles had enjoyed near-complete freedom to make the

Quest for Glory games exactly as they wanted them, and were unused to working from someone else’s brief. They wanted to make their

Shannara game an heir to their previous series in the sense of including a smattering of CRPG elements, including a combat engine. Bob Bates, a self-described “adventure-game purist,” saw little need for them, but, perhaps unwisely, never put his foot down to absolutely reject their inclusion. Instead they remained provisionally included — included “for now,” as Bob wrote in February — as the weeks continued to roll by. In July, with the ship date just a few months away, combat was still incomplete and thus untested on even the most superficial level. “This would have been a good time to drop it,” admits Bob, “but we did not.”

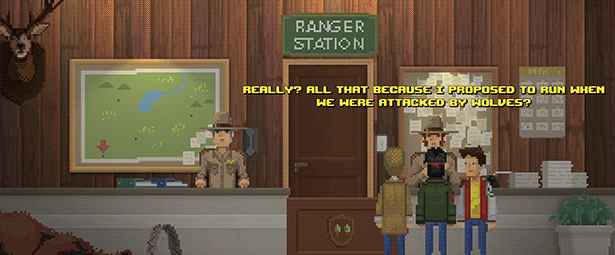

While the one source of tension arose from a feature that the Coles dearly wanted and Bob Bates found fairly pointless, the other was to some extent the opposite story. From the very beginning, Bob had wanted the game to include an “emotion-laden scene” near the climax that would force the player to make a truly difficult ethical decision, of the sort with no clear-cut right or wrong answer. The Coles had agreed, but without a great deal of enthusiasm on the part of Lori, the primary writer of the pair. Considering Bob’s cherished ethical dilemma little more than a dubious attempt to be “edgy,” she proved slow to follow through. This caused Bob to nag the Coles incessantly about the subject, until Lori finally wrote a scene in which the player must decide the fate of Shella, the daughter of another character from the first novel and a companion in Jak’s adventures. (We’ll return to the details and impact of that scene shortly.)

But the ironic source of the biggest single schedule killer was, as Corey Cole puts it, having too few constraints rather than too many: “A mentor once told me that the hardest thing [to do] is to come up with an idea, or build something, with no constraints.” Asked by Bob Bates what they might be able to do to make the game even better if they had an extra $50,000 to hand, the Coles, after scratching their heads for a bit, suggested adding some pre-rendered 3D cut scenes. “If I had known then what I found out by the end of the project,” says Corey, “I’d have said, ‘No, thanks, we’ll finish what we started.’ I ended up sleeping at the office, since each render required hand-tweaking and took about four hours.”

Still more problems arose as the months went by. The father of the art director had a heart attack, and his son was forced to cut his working hours in order to care for him. Another artist — the same one who “simply isn’t producing” in the memo extract above — finally confessed to having terminal cancer; he wished to continue working, and no one involved was heartless enough not to honor that request, but his productivity was inevitably affected.

Legend had agreed to handle quality control themselves from the East Coast. But in these days before broadband Internet, testing a game of 500 MB or more from such a distance wasn’t easy. Bob Bates:

All development work had to cease while a CD was being burnt. Then it was Fed-Exed across the country, and then we would boot it. Sometimes it just didn’t work, or if it did work, there would be a fatal bug early in the program. The turnaround cycle on testing was greatly reducing our efficiency. By the time testers reported bugs, the developers believed they had already fixed them. Sometimes this was true, sometimes it wasn’t.

On October 2, 1995, about five weeks before the game absolutely, positively needed to be finished if it was to reach store shelves in time for Christmas, Bob Bates delivered another damning verdict after his latest trip to Oakhurst:

* There is no doc for the rest of the handling in the game. [This cryptic shorthand refers to “object-on-object handling,” a constant bone of contention. Bob perpetually felt like the game wasn’t interactive enough, and didn’t do enough to acknowledge the player’s actions when she tried reasonable but incorrect or unnecessary things. Lori Ann Cole, says Corey, “felt that would distract players from the meaningful interactions; she refused to do that work as a waste of her time, and potentially harmful to her vision of the game.”]

* The final game section is not coded.

* Combat is not done.

* Lots of screen flashes and pops.

* Adventurer’s Journal is not done.

* Too many long sequences of non-interaction.

* Too many places where author’s intent is not clear.

* Map events (major transitions) are not done.

* Combat art is blurred.

* Final music hasn’t arrived from composer.

As Bob saw it, there was only one alternative. He flew Corey Cole and one other Oakhurst-based programmer to Virginia and started them on a “death march” alongside whatever Legend personnel he could spare. Legend was struggling to finish up

Mission Critical at the same time, meaning they were suddenly crunching two games simultaneously. “The fall of 1995 was really enjoyable at Legend,” Bob says wryly. “We coded like hell until the thirteenth of November. We hand-flew the master to the duplicators and the game came out Thanksgiving week. Irreparable damage [was done] to the team. We have not worked together since.” The final cost of the game wound up being $528,000.

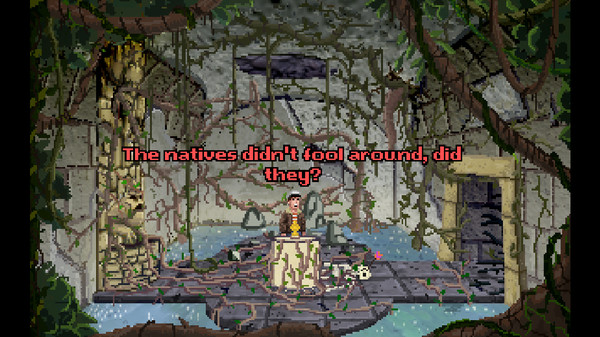

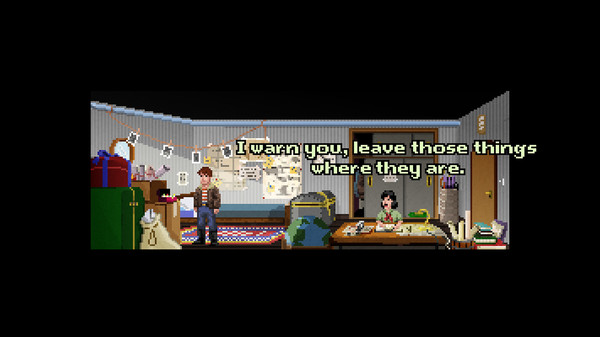

The scale of Legend’s great Problem Project is commensurable with the company’s size and industry footprint. The development history of

Shannara isn’t an epic that stretches on for years and years, like LucasArts’s

The Dig; still less is it a tale of over-the-top excess, like Ion Storm’s

Daikatana.

Shannara didn’t even ship notably late by typical industry standards. Still, everything is relative: as a small company struggling to survive in an industry dominated more and more by a handful of big entities, Legend simply couldn’t afford to let a project drag on for years and years. In their position, every delay represented an existential threat, and outright cancellation of a project into which they’d invested significant money was unthinkable. For those inside Legend, the drama surrounding

Shannara was all too real.

But the

Shannara story does have an uncommon ending for tales of this stripe: the game that resulted is… not so bad at all, actually.

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)