“Around the time I was working on a design for

Moebius, I began reading gay romance,” Jensen says. “I’d read some isolated things before — Anne Rice and gay fiction like

Maurice. But I discovered gay romance and found it fun and intriguing. I decided to try my hand at writing a few short stories and sent them to a publisher, who accepted them.” Since 2013, under the pen name Eli Easton, Jensen has written truly dozens of stories about gay romance—starring nerds, jocks, ex-military, sheriffs, angles, nurses, reclusive authors, Pennsylvania farmers, single dads, werewolves and Santa Claus—and now self-publishes, with a new title every few months.

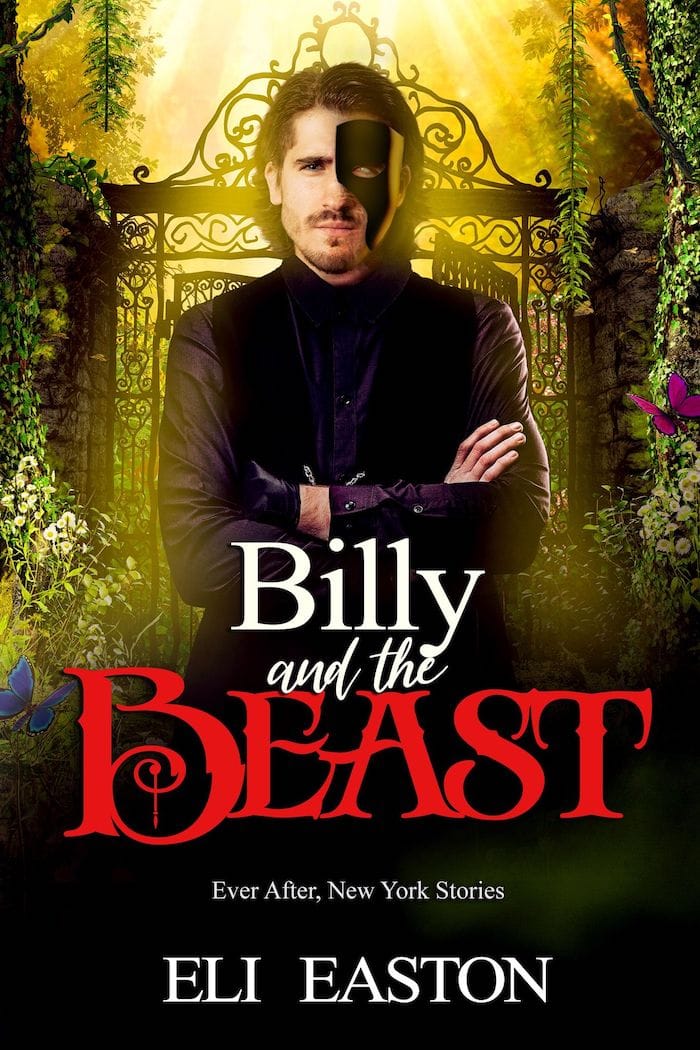

Billy and the Beast, an adaptation of guess what, reads like a gay retelling of

Gray Matter (“There was something about him... handsome, masked, menacing.... Nothing this cool ever happened to me” and is absolutely of a piece with Jensen's past work. Her romance writing eschews esoteric mystery and deadly stakes, but the characters and their voices are the same, and the boldness that expressed itself in Gabriel Knight as audacity and opera is felt here through unabashed intimacy and appreciation of pleasure.

As a writer, Jensen’s always been more interested in her men—Gabriel Knight and David Styles are more sexual entities than their love interests—so it’s not wholly surprising this is where she should wind up exclusively focusing her gaze. “I’m crap at writing very feminine female characters. And, similarly, I don’t care for traditional [male-female] gender dynamics,” she says. “I was tested in a college psychology class once and my personality tested dead in the middle—androgynous. I tend to be most comfortable in that zone. Most of my main characters are neither hyper-masculine nor hyper-feminine…. It’s hard for me to write those kinds of characters from a place of truth. I’m more comfortable in the LGBTQ space where personalities and gender dynamics are in the middle.”

The cover of Billy and the Beast

It is working for her. Thousands of readers rate Easton’s novels on Goodreads, always highly: “I love Eli’s writing…. It’s perfectly kinky while still being amazingly sweet.” “Died from shock after Eli Easton melted [my] cold, black heart into a puddle of goo.” “Eli Easton dared, and I love her for that.” “Eli Easton, your readers need some butt sex and we need it yesterday."

As Easton, Jensen attends conventions, does collaborations and guest stories in anthologies, and engages happily and often with her fans. She enjoys the kind of success and passionate audience that has eluded her since

Gabriel Knight.

“I’ve come to love writing as Eli Easton,” she says, “[and] being part of a community you respect and enjoy is important too. About the time I completed

Moebius, GamerGate broke. And there was so much toxicity, especially toward female designers. I wasn’t sorry to leave that behind.”

For now, anyway, Jensen is living her dream, as she originally dreamed it: she is a novelist whose books sell better than her games. The frictionless speed with which Jensen has found success in this niche is the absolute inverse of her experience of writing

Dante’s Equation. That had been so difficult, and for such little reward: surely that wasn’t what she was supposed to be doing?

Getting back into games, the logical alternative, might not have wholly worked, but it clarified Jensen to her essential writing self. Jensen’s always been a romance writer, and always a writer of romantic men. The decline of the adventure game forced her out of studio environments into independence, which suited her: she’s an auteur, not a collaborator, who wants to write alone on stories that are, in and of themselves, the product and the whole point: not directions for developers to interpret or publishers to cut down. While she struggled with

Gray Matter and Pinkerton Road, she was finding a perfect creative outlet for the writer she always has been.

“Am I a better game designer than a novelist? Probably,” she says today—but has Jane Jensen not been kind of both those things all at once? Eli Easton is not a career swerve but the fulfilment of the promise of Jensen’s second

Gabriel Knight, back in 1995, which blisters with unconsummated attraction between Gabriel and a libertine, bisexual werewolf. “An indication that I’ve always been fascinated by the homoerotic,” Jensen says. An indication that—like the student ID Sam Everett hides in one hand while appearing to toss it into a shredder—was always there, in plain sight.