RPG Codex Report: Wasteland 2 Release Party

RPG Codex Report: Wasteland 2 Release Party

Editorial - posted by Crooked Bee on Mon 29 September 2014, 12:11:35

Tags: Brian Fargo; Chris Avellone; Colin McComb; George Ziets; inXile Entertainment; Kevin Saunders; Nathan Long; Steve Dobos; Wasteland 2Sometime in early 2012, when InXile's sequel to the 1988 cult classic RPG Wasteland was being crowdfunded, we at the RPG Codex ran our own fundraiser campaign for a Codex-themed in-game location and statue. When Wasteland 2 was finally released earlier this month, we got what we paid for -- have you found our in-game shrine already? -- which, incidentally, also included an invitation for two persons to attend the Wasteland 2 Release Party on September 19th in Newport Beach, CA, where the two lucky invitees would party, drink, and celebrate with the likes of Brian Fargo and Chris Avellone.

We wanted to find someone local to go on our behalf, but as it happens none of our staff or regular contributors live in California. So we turned to the esteemed community member MRY, who happens to live close to Newport and who in his turn suggested the Californian artist/writer/music critic Daniel Miller (http://bydanielmiller.com/). Together, they went to the party on the Codex's behalf and also did two independent write-ups about what they saw and did there and how it all went.

Friday Night at Saddle Ranch

by Daniel Miller

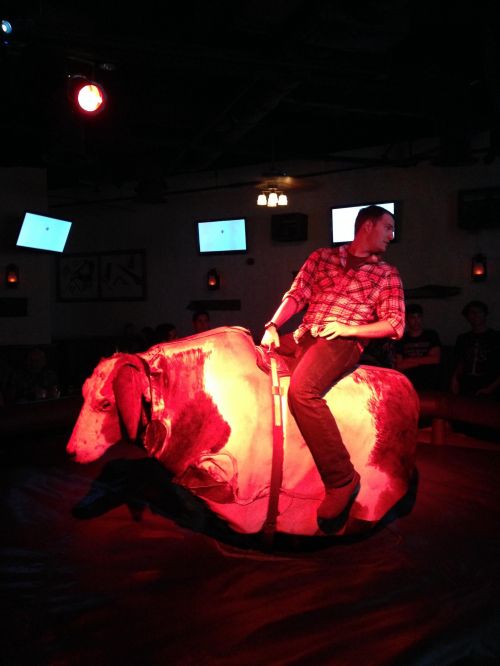

The release party for Wasteland 2. An hour drive down the 110 towards Newport Beach, and we’re in a land of mall fashion, a beach suburbia. The kind of place that typifies the excessive stereotypes of housewife reality TV, or so I’ve heard. With any luck, the horror of the American standard would mirror the content of a post apocalypse, and the evening would harmonize well. The venue was a bar and grill built out of an airplane hangar so as to accommodate the throng of spectators to the mechanical bull. I found the Wasteland group scattered unobtrusively on the patio, standing humbly. Plump, fresh faces with drink in hand and drink ticket in other hand. A nod to Mark Yohalem, and I promptly began my journalistic duties by ordering a tall whisky.

By and large, to speak to the leaders of InXile is to have that confident and capable conversation on games that any opinionated gamer has always wanted. These are people not only equipped with a passion for their craft, but the utility to bring it to the player without polluting the game. I couldn’t find a hint of wistfulness at the warchest days of pre-Kickstarter funding, and each one seemed to remember exactly where, when and on which rig they first booted up Wasteland 1. I’m reticent to use the word artist, simply because they seem so capable, but whether or not their games deliver person-to-person, I’m certain that the intent is there. There is a sense of unity in their team as well, as though each member has been consulted and feels represented. And they all speak with great pride about the community that has developed around the game. It seems like a fantastic company and team, and an incredibly honest product. Which is of course terrible for news, so I tried to start bringing up the Codex in conversation.

Chris Avellone, by Daniel Miller

What goes on in the darkened halls of the Codex? Told that I was there writing a report for the site, those that knew would produce a pained sort of smile, observe the impressive tenure or wide readership of the Codex, and admit their own varied past with the site. Then a pause, and remembrance of a place on the internet where good ideas (and decency) are harried, tortured, profaned, shredded and whittled to oblivion. Of course there was talk of the incredible depth reached in conversations on the site, and there was talk of diamonds in the rough (the handle Jaesun?). Brian Fargo likened RPG Codex to Howard Stern in that it had at some point gone off the cliff and never returned, and a wild-eyed whiskered fellow remarked that perhaps the in-game Codex statue should have had smaller genitals.

This fellow was promptly hushed by Joby Bednar, ready to regale me with feats of code. This man personally built a 6502 emulator to embed into Wasteland 2, which allows the tech-savvy player access to a 64k computer right from an in-game terminal. Thus, a player can insert their very own 6502 programs and use them within Wasteland. Beyond this, there are apparently hundreds of other little tidbits scattered throughout the game, but Joby was thankfully forthright with a hint exclusive to this article: In a missile silo, there is a console which allows for player input. Type the word ‘Joshua’.

With that, Joby drifted away, and I noticed that a few had occupied a booth away from the group. At this table was a prominent member of SomethingAwful, name of Quarex, who informed me that we were tacit enemies. Seated around him were the scripters, the soldiers, whom I was hoping would be eager to gripe. With hands flailing, Ben Moise confessed the great labor that went into making sure that everyone was killable in Wasteland 2. In fact, a few people had a complaint about that feature, and it ended up being a favored question of the evening.

It would seem that most employees grudgingly accept the freedom of murder as an expected feature of the series. Asking the question in a more general sense though, I found a great deal of discomfort on the topic. A couple of people asked me if their answers would be on the record. The self-purported moral compass of the group cited her experience as a parent. A few were more diplomatic, saying that freedom to kill is necessary according to the needs of a specific game. When I finally got my moment with Kevin Saunders, he made raised more practical concerns: the feature was costly in time and effort and precluded child characters, unlike in Tides of Numenera.

After shoving violence around for a while, I landed at the table with novelist-turned-game writer Nathan Long and a steely black-haired woman who was not satisfied with the complimentary shots. Nathan had been described to me as the wild card of the group, and in his exasperation at waiter incompetence there was certainly the flicker of the unknown. Bewildered, I stepped away, and amidst a whopping world-record-breaking 25 minute bull ride by Technical Director and American hero John Alvarado, the Obsidian pinpoint of Chris Avellone’s eye became fixed on me, and would not relent until a shot from each UN member-state was arguing in my brain.

From there, the night gets blurry. Murmurs that Bethesda had tried to shut Steam down the day of the Wasteland 2 launch; perhaps only half in jest. Brian Fargo lamenting his Hearthstone addiction, decreeing that Sacrifice was the best multiplayer game of all time, dropping a drink while talking about the movie ‘Her’ (which was written in my notes as ‘mother’ for some reason).

I’ll close with remembering Matt Findley. Has turn-based dreams. President of InXile and one-time general manager of interplay Europe. With it since the beginning, very successful dude. When asked which is the least favourite game that he had made, he lamented not only the game ‘Purr Pals,’ but its vast profits. He said that directing Interplay Europe, achieving this ‘success’, didn’t make him happy because he just wanted to make good games. Well this reporter, and it would seem the community at large, are glad he did.

inXile, At Home

by MRY

"Man ist," as the Germans say, "was man isst." But it also sometimes seems that man is where he eats. And so it is with no small amount of trepidation that I survey the Saddle Ranch Chop House: a chain, shopping-mall-anchor restaurant with transparently ersatz "authenticity," a call-back to a kind of Texas honky tonk that exists only in the heads of those who get no closer to Texas than slathering grocery store BBQ sauce on steamed brisket. It is a restaurant that trades on inauthenticity, slickness, and its customers' vicarious nostalgia. Fuck, is this the Bard's Tale launch party?

It doesn't help that I've sat in traffic for almost two hours, wondering (as is my wont) what possible justification all these drivers could have for going the same way I'm going. It doesn't help that it seems like the long days of summer have just ended. It doesn't help that I can barely hear my already-half-hoarse voice over the lame music blasting from the speakers. "Yeah," the waitress says, "that group over there," pointing toward a terrifying crowd in which I recognize exactly no one. Why, exactly, did I think this was a good idea? How, exactly, do I get myself into these things?

* * *

I'm nine years old, and I'm at Egghead Software at Wisconsin and Van Ness in Washington, DC. I can see the shelves, the faded carpeting, the bargain bins, the balding cashier. I can't remember your name and you literally just introduced yourself to me, but every detail of that store -- like all childhood memories -- is imprinted in indelible ink.

At the back of the store, on the second shelf from the floor, is the iconic Wasteland box. A sticker identifies the game as PG-13. It will be the first computer RPG I ever played; I've wet my toes in Dragon Warrior for the Nintendo, I've watched a terribly nerdy friend play Ultima V, but that's it. I pick up the box and bring it to my mom. She raises an eyebrow at the PG-13. "It's just marketing," I tell her, in whatever juvenile way I can express the concept. She agrees, and buys it. I believe she spent more on that game ($40, I think?) than I've spent on any game in the past decade; we live in a golden age of cheap media.

I never did beat Wasteland, even though I went back to it time and again over the years. As best I can recall, I stopped playing at the sewers. (For how many dozens of RPGs is that sad statement true?)

All the same, I could recount a hundred stories. Trying desperately to tie up Bobby's dog. Half-weeping as I had to shoot my way out of Highpool. Blood sausage. A misaimed howitzer. The best mayor a kid in DC could hope for. Dancing on tables. Faran Brygo. Sweating, unable to sleep, after reading a paragraph in the book that said I had been cheating and the police were coming to get me. Wondering for most of my life whether, in fact, you got to go to Mars at the end of the game. Scorpitrons. "Mom, what's 'herpes'?"

Now I'm 34 years old, and I'm recounting that last bit to Brian Fargo. "And that's how I learned about safe sex," I conclude, as he glances in horror toward his two young kids standing next to him. Shit. "How, exactly," he thinks, "do I get myself into these things?"

* * *

Talking to Fargo impresses several things upon me. The first is how young this industry is. Fargo's career seems to span most of its meaningful history -- I know, Chester Bolingbroke would say I'm leaving out decades of PLATO games -- and in fact covers my entire lifetime as a gamer, including almost every high point in it. And yet he's a youthful 50, and his kids are hardly older than mine. At various times over the night he describes himself as "just an entertainer" and "a gamer at heart"; in fact, he is at once an elder statesman and new frontiersman.

He's also, quite obviously, a shrewd businessman who has survived tremendous upheavals both in his own career and in the industry as a whole. At one point, he mentions that when doing a deal, he looks at the other side's headquarters on Google Maps and gets a feel for how lavishly they live. "It says one thing if they're in a strip mall. It says something else if they're in a palace." (*cough*Double Fine*cough*) I get the sense that he's had both sets of digs in his days.

The same savvy that has served him so well makes me cautious about drawing any conclusions about Fargo's inner character. He certainly seemed charming, sincere, generous with his time and attention, a doting dad, a gentle boss, a true believer in games, and so on. But, as the Bard wrote, "One may smile, and smile, and be a villain -- at least I am sure it may be so in Newport." Or something like that. I want to believe in him -- and I have no reason not to -- but I wouldn't stake my life on it.

Still, to listen to the man talk about games he's played, games he's made, games he's dreaming of making, it's hard not to fall a little bit in love. He complains passionately about reviewers who can't, or won't, understand complex RPGs, and vows that next time he's following Larian's lead and not distributing advance review copies. At one point, he declares that Sacrifice is the best multiplayer game of all time. Sacrifice happens to be one of my all-time favorites -- for the art design, the voice acting, the writing (which combines po-faced Soul Reaver-ism with sly subversiveness and lots of wordplay) -- but in my opinion the multiplayer is trash. I tell him as much, and he rolls his eyes. "I'm sure you weren't playing it 3 on 3." He's right. He launches into stories of thrilling matches over the years, of hustling kids in some tournament, of little cheats to juggle enemy wizards. The word "manahoar" rolls off his tongue with practiced fluency.

I want to believe.

Midway through the night, I'm already certain about how I'll feel when it's over, and I'm right: this is something special. The pronoun is deliberately vague as to its antecedent.

I think "this" might mean inXile. The creative talent they've assembled -- and I'm speaking mostly on the design and writing side; I know less about the other elements -- is remarkable. When you play with toys as a kid, you sometimes put together your dream-team of Man-E-Faces, Leader-1, the blue hand M.U.S.C.L.E. Man, and Ziggy, and send them on the most challenging of adventures.

(What? That's not your dream team? You want Snake-Eyes and Optimus Prime and Hulk Hogan? Well, we'll agree to disagree.)

The inXile team feels like such a league of extraordinary gentlemen, selected as if bespokedly to fit exactly my own life of computer-game passions. Wasteland, Fallout, Mask of the Betrayer, Planescape: Torment . . . . Short of shang-hai'ing the Gollop Brothers, Paul Reiche, and Fred Ford, it's hard to imagine how it could get much better.

Now, "this" might also mean the experience of the night itself. You know how people ask, "If you could have dinner with any five people, who would they be?" Then imagine you invite them over to dinner, and Abraham Lincoln has an oozing hole in his head and he keeps going on and on about his fucking Marfan Syndrome, and Mark Twain says, "Pull my finger" and is just farting the whole damn time. Or, probably, they'd all just rather talk to each other than to you, because, seriously, is there any chance -- ANY CHANCE! -- that you would be on the magical dinner list of any of those people? Fuck no.

So when you assemble all your game-making idols in one place, isn't there a very real risk of discovering that they're a bunch of jerks, or that they think you're a loser to be treated at best with transparent condescension and even that courtesy only because they mistakenly think that you, personally, backed Wasteland 2 for $10,000 when in fact you haven't even bought the game because you refuse to pay more than $10 for anything because we live in a golden age of cheap media?

Very real, indeed.

But, it turns out, my neurotic fears were totally misplaced. Despite (or perhaps because of) looking like Ming the Merciless, Colin McComb has a gentle, erudite friendliness and a willingness to be teased by a loser like me that seem out of place for man who could create such an abomination as the bladesinger.* Avellone -- too cool, I think, to be the tortured soul I imagined when playing Torment -- took my idolatry in good stride, and we traded stories of youthful excess. George Ziets and I talked about emotions that games seldom touch upon -- melancholy, ennui. I groused to him and Kevin Saunders about the stupid Venetian Carnival mask I had to wear in MOTB to boost my charisma; when I lavished them with praise for their intelligent use of transitional text in loading screens, they drilled down into other non-traditional mechanisms for conveying story.

It's hard -- in part because I wasn't taking notes, in part because in my own mind it's all a gestalt -- to try and recount every bon mot and clever design trick they dished out. It's easier to talk about things at a high level, and from that vantage, three things stand out like the Great Wall (which is not the only man-made object visible from space, but it's a useful trope; try using more than 10% of your brains!):

(1) These guys really think hard about games and how to tell stories through games. I've been privileged to talk with people at a fair number of game companies about story-telling, and while everyone aims high and does their level best, there was a difference in kind between the inXile / Obsidian crowd and people I've spoken to before.

Specifically, there sometimes seems to be a gap in the passion and attention that gamers pay to games and the passion and attention that game-creators pay to games. This, to me, is why the Codex -- despite its many faults (or perhaps because of them) -- is so important: the level of analysis that the Codex has been doing for over a decade is unparalleled (Emily Short's interactive-storytelling analysis is too different to compare, but equally important). Ordinarily, if you try to engage a game-creator at that level of discussion, it's impossible. Not so with these guys. Far from responding with glassy-eyed bemusement, they gave better than they got.

(2) They are passionate about story-telling in a broader sense, which means they are avid readers, watchers, players, and they engage in this consumption with a critical eye. While I don't read or watch or play as much as I used to, I'm accustomed to being able to name-drop obscure works to outflank my interlocutors; here, however, I found the inXile folks were already familiar with almost everything I whipped out. (It was quite delightful to meet people who also admire Barbarian Prince.)

(3) They're nice guys. This was supposed to be their night, where -- among friends -- they would let their hair down (Colin excepted) and celebrate the fruit of months of sweat, toil, and tears. Instead, they spent it entertaining a handful of geeky randos.

It would have been easy -- and appropriate, even -- to seat us at a kids' table, stop by, slap some backs, shake some hands, buy a round of drinks, and then go back to the grown-ups' table. But that's not at all what they did. To the contrary. At one point midway through the night, I found myself retreating awkwardly into a corner like a middleschooler at a dance party, not comfortable intruding further, especially since everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves. Colin found me, grabbed me, said, "Hey, there's some more guys I bet you'd like to meet," and sat me down among another friendly group.

The fact that they seemed genuinely excited to meet the backers speaks volumes. Unlike Fargo, who as a businessman may well have been capable of poker-facing his way through the whole night, these guys did not seem willing or able to engage in that kind of glad-handing. Rather, despite years of grizzling, they still had the bloom of new creators who are delighted and surprised that people could be so interested in their creations, and flattered by the attention (and generosity) their fans had shown them.

Earlier, I said that Fargo made me realize how young the industry is. But in fact, the inXile crowd exuded thoughtful maturity as much as youthful enthusiasm. At one point I told them that my biggest fear for Torment: Tides of Numenera was that it would capture PS:T's essence and yet not engage me, and that as a result I would conclude that I had fallen in love with PS:T not because it was "objectively great" (whatever that might mean) but because the themes that seemed so well developed were in fact little more than sophomoric musings on adolescent passions, perfect for a self-absorbed 19 year old. (I was a little less pretentious in saying it than I have been in writing it.)

Their response was measured and careful. In essence, I was told not to forget that decades have passed, and that the folks making T:TON are not the same people they were when they worked on (or fell in love with) PS:T. Loss, suffering, and change mean different things to a middle-ager than they did to a young adult.

Embedded in this answer was something that gave me great hope: the premise that the team was attempting to convey the living spirit of PS:T that still moved inside them rather than -- like John Hammond -- trying to extract the dead DNA frozen in the amber of the old game itself. Put otherwise, they seemed to say they were exploring themes that matter to them now, not themes that mattered to other players years and years ago.

I say that it gave me great hope, but it causes me some nervousness, too. Sometimes creators love their creations for the wrong reasons and, if left to their own devices, try to beautify things with the crudest of plastic surgeries. (This was Newport Beach, after all.) And we've all seen one nightmare after another emerge from the dream of modernizing the classics while "capturing the spirit of the original."

Still, what I think we all loved in PS:T was the way it felt like a personal game, not the creation of a corporate focus-group. And, for all their successes -- for all they were celebrating in the most corporate-focus-group-ish of venues -- I cannot imagine this team succumbing to the urge to pander.

* * *

I drove home on long, dark, empty freeways with plenty of time to think about the people I'd met at the party. It is exactly in such circumstances that my cynicism swells to fill the emptiness around me. Was Fargo just a salesman? Were the backers just being treated like mascots by the cool kids? Had I gone all that way for nothing?

But, for once, these doubts crawled away of their own accord. Rabbi Heschel says of the "self-suspicious man" that, "living in fear, he thinks that ambush is the normal dwelling-place of all men." But that isn't where most men live. Not all dreams turn to nightmares; not all friendliness is smarm.

For once, for now, I'll believe that things really are as good as they seem at inXile, and I will merely . . .

-----------

(* True story: While at nerd camp as a kid, I played AD&D for the first time, and wound up DMing. One of the other nerds had brought a bladesinger character sheet from home, and as I read over his abilities, I was incredulous. No fucking way that's how the rules work. Dude has to be lying. But he whined and wheedled, and who really cares, I can just throw mithril-armed super-orcs at him. I had largely forgotten about this incident until Colin made his YouTube apology, and I discovered that he had managed to design a class so stupid that even someone who knew nothing about AD&D rules could tell it was broken. When I needled him about this, he replied, "You don't have to worry, I'm not doing any balance work on Torment.")

We wanted to find someone local to go on our behalf, but as it happens none of our staff or regular contributors live in California. So we turned to the esteemed community member MRY, who happens to live close to Newport and who in his turn suggested the Californian artist/writer/music critic Daniel Miller (http://bydanielmiller.com/). Together, they went to the party on the Codex's behalf and also did two independent write-ups about what they saw and did there and how it all went.

Friday Night at Saddle Ranch

by Daniel Miller

The release party for Wasteland 2. An hour drive down the 110 towards Newport Beach, and we’re in a land of mall fashion, a beach suburbia. The kind of place that typifies the excessive stereotypes of housewife reality TV, or so I’ve heard. With any luck, the horror of the American standard would mirror the content of a post apocalypse, and the evening would harmonize well. The venue was a bar and grill built out of an airplane hangar so as to accommodate the throng of spectators to the mechanical bull. I found the Wasteland group scattered unobtrusively on the patio, standing humbly. Plump, fresh faces with drink in hand and drink ticket in other hand. A nod to Mark Yohalem, and I promptly began my journalistic duties by ordering a tall whisky.

By and large, to speak to the leaders of InXile is to have that confident and capable conversation on games that any opinionated gamer has always wanted. These are people not only equipped with a passion for their craft, but the utility to bring it to the player without polluting the game. I couldn’t find a hint of wistfulness at the warchest days of pre-Kickstarter funding, and each one seemed to remember exactly where, when and on which rig they first booted up Wasteland 1. I’m reticent to use the word artist, simply because they seem so capable, but whether or not their games deliver person-to-person, I’m certain that the intent is there. There is a sense of unity in their team as well, as though each member has been consulted and feels represented. And they all speak with great pride about the community that has developed around the game. It seems like a fantastic company and team, and an incredibly honest product. Which is of course terrible for news, so I tried to start bringing up the Codex in conversation.

Chris Avellone, by Daniel Miller

What goes on in the darkened halls of the Codex? Told that I was there writing a report for the site, those that knew would produce a pained sort of smile, observe the impressive tenure or wide readership of the Codex, and admit their own varied past with the site. Then a pause, and remembrance of a place on the internet where good ideas (and decency) are harried, tortured, profaned, shredded and whittled to oblivion. Of course there was talk of the incredible depth reached in conversations on the site, and there was talk of diamonds in the rough (the handle Jaesun?). Brian Fargo likened RPG Codex to Howard Stern in that it had at some point gone off the cliff and never returned, and a wild-eyed whiskered fellow remarked that perhaps the in-game Codex statue should have had smaller genitals.

This fellow was promptly hushed by Joby Bednar, ready to regale me with feats of code. This man personally built a 6502 emulator to embed into Wasteland 2, which allows the tech-savvy player access to a 64k computer right from an in-game terminal. Thus, a player can insert their very own 6502 programs and use them within Wasteland. Beyond this, there are apparently hundreds of other little tidbits scattered throughout the game, but Joby was thankfully forthright with a hint exclusive to this article: In a missile silo, there is a console which allows for player input. Type the word ‘Joshua’.

With that, Joby drifted away, and I noticed that a few had occupied a booth away from the group. At this table was a prominent member of SomethingAwful, name of Quarex, who informed me that we were tacit enemies. Seated around him were the scripters, the soldiers, whom I was hoping would be eager to gripe. With hands flailing, Ben Moise confessed the great labor that went into making sure that everyone was killable in Wasteland 2. In fact, a few people had a complaint about that feature, and it ended up being a favored question of the evening.

It would seem that most employees grudgingly accept the freedom of murder as an expected feature of the series. Asking the question in a more general sense though, I found a great deal of discomfort on the topic. A couple of people asked me if their answers would be on the record. The self-purported moral compass of the group cited her experience as a parent. A few were more diplomatic, saying that freedom to kill is necessary according to the needs of a specific game. When I finally got my moment with Kevin Saunders, he made raised more practical concerns: the feature was costly in time and effort and precluded child characters, unlike in Tides of Numenera.

After shoving violence around for a while, I landed at the table with novelist-turned-game writer Nathan Long and a steely black-haired woman who was not satisfied with the complimentary shots. Nathan had been described to me as the wild card of the group, and in his exasperation at waiter incompetence there was certainly the flicker of the unknown. Bewildered, I stepped away, and amidst a whopping world-record-breaking 25 minute bull ride by Technical Director and American hero John Alvarado, the Obsidian pinpoint of Chris Avellone’s eye became fixed on me, and would not relent until a shot from each UN member-state was arguing in my brain.

From there, the night gets blurry. Murmurs that Bethesda had tried to shut Steam down the day of the Wasteland 2 launch; perhaps only half in jest. Brian Fargo lamenting his Hearthstone addiction, decreeing that Sacrifice was the best multiplayer game of all time, dropping a drink while talking about the movie ‘Her’ (which was written in my notes as ‘mother’ for some reason).

I’ll close with remembering Matt Findley. Has turn-based dreams. President of InXile and one-time general manager of interplay Europe. With it since the beginning, very successful dude. When asked which is the least favourite game that he had made, he lamented not only the game ‘Purr Pals,’ but its vast profits. He said that directing Interplay Europe, achieving this ‘success’, didn’t make him happy because he just wanted to make good games. Well this reporter, and it would seem the community at large, are glad he did.

inXile, At Home

by MRY

"Man ist," as the Germans say, "was man isst." But it also sometimes seems that man is where he eats. And so it is with no small amount of trepidation that I survey the Saddle Ranch Chop House: a chain, shopping-mall-anchor restaurant with transparently ersatz "authenticity," a call-back to a kind of Texas honky tonk that exists only in the heads of those who get no closer to Texas than slathering grocery store BBQ sauce on steamed brisket. It is a restaurant that trades on inauthenticity, slickness, and its customers' vicarious nostalgia. Fuck, is this the Bard's Tale launch party?

It doesn't help that I've sat in traffic for almost two hours, wondering (as is my wont) what possible justification all these drivers could have for going the same way I'm going. It doesn't help that it seems like the long days of summer have just ended. It doesn't help that I can barely hear my already-half-hoarse voice over the lame music blasting from the speakers. "Yeah," the waitress says, "that group over there," pointing toward a terrifying crowd in which I recognize exactly no one. Why, exactly, did I think this was a good idea? How, exactly, do I get myself into these things?

* * *

I'm nine years old, and I'm at Egghead Software at Wisconsin and Van Ness in Washington, DC. I can see the shelves, the faded carpeting, the bargain bins, the balding cashier. I can't remember your name and you literally just introduced yourself to me, but every detail of that store -- like all childhood memories -- is imprinted in indelible ink.

At the back of the store, on the second shelf from the floor, is the iconic Wasteland box. A sticker identifies the game as PG-13. It will be the first computer RPG I ever played; I've wet my toes in Dragon Warrior for the Nintendo, I've watched a terribly nerdy friend play Ultima V, but that's it. I pick up the box and bring it to my mom. She raises an eyebrow at the PG-13. "It's just marketing," I tell her, in whatever juvenile way I can express the concept. She agrees, and buys it. I believe she spent more on that game ($40, I think?) than I've spent on any game in the past decade; we live in a golden age of cheap media.

I never did beat Wasteland, even though I went back to it time and again over the years. As best I can recall, I stopped playing at the sewers. (For how many dozens of RPGs is that sad statement true?)

All the same, I could recount a hundred stories. Trying desperately to tie up Bobby's dog. Half-weeping as I had to shoot my way out of Highpool. Blood sausage. A misaimed howitzer. The best mayor a kid in DC could hope for. Dancing on tables. Faran Brygo. Sweating, unable to sleep, after reading a paragraph in the book that said I had been cheating and the police were coming to get me. Wondering for most of my life whether, in fact, you got to go to Mars at the end of the game. Scorpitrons. "Mom, what's 'herpes'?"

Now I'm 34 years old, and I'm recounting that last bit to Brian Fargo. "And that's how I learned about safe sex," I conclude, as he glances in horror toward his two young kids standing next to him. Shit. "How, exactly," he thinks, "do I get myself into these things?"

* * *

Talking to Fargo impresses several things upon me. The first is how young this industry is. Fargo's career seems to span most of its meaningful history -- I know, Chester Bolingbroke would say I'm leaving out decades of PLATO games -- and in fact covers my entire lifetime as a gamer, including almost every high point in it. And yet he's a youthful 50, and his kids are hardly older than mine. At various times over the night he describes himself as "just an entertainer" and "a gamer at heart"; in fact, he is at once an elder statesman and new frontiersman.

He's also, quite obviously, a shrewd businessman who has survived tremendous upheavals both in his own career and in the industry as a whole. At one point, he mentions that when doing a deal, he looks at the other side's headquarters on Google Maps and gets a feel for how lavishly they live. "It says one thing if they're in a strip mall. It says something else if they're in a palace." (*cough*Double Fine*cough*) I get the sense that he's had both sets of digs in his days.

The same savvy that has served him so well makes me cautious about drawing any conclusions about Fargo's inner character. He certainly seemed charming, sincere, generous with his time and attention, a doting dad, a gentle boss, a true believer in games, and so on. But, as the Bard wrote, "One may smile, and smile, and be a villain -- at least I am sure it may be so in Newport." Or something like that. I want to believe in him -- and I have no reason not to -- but I wouldn't stake my life on it.

Still, to listen to the man talk about games he's played, games he's made, games he's dreaming of making, it's hard not to fall a little bit in love. He complains passionately about reviewers who can't, or won't, understand complex RPGs, and vows that next time he's following Larian's lead and not distributing advance review copies. At one point, he declares that Sacrifice is the best multiplayer game of all time. Sacrifice happens to be one of my all-time favorites -- for the art design, the voice acting, the writing (which combines po-faced Soul Reaver-ism with sly subversiveness and lots of wordplay) -- but in my opinion the multiplayer is trash. I tell him as much, and he rolls his eyes. "I'm sure you weren't playing it 3 on 3." He's right. He launches into stories of thrilling matches over the years, of hustling kids in some tournament, of little cheats to juggle enemy wizards. The word "manahoar" rolls off his tongue with practiced fluency.

I want to believe.

Midway through the night, I'm already certain about how I'll feel when it's over, and I'm right: this is something special. The pronoun is deliberately vague as to its antecedent.

I think "this" might mean inXile. The creative talent they've assembled -- and I'm speaking mostly on the design and writing side; I know less about the other elements -- is remarkable. When you play with toys as a kid, you sometimes put together your dream-team of Man-E-Faces, Leader-1, the blue hand M.U.S.C.L.E. Man, and Ziggy, and send them on the most challenging of adventures.

(What? That's not your dream team? You want Snake-Eyes and Optimus Prime and Hulk Hogan? Well, we'll agree to disagree.)

The inXile team feels like such a league of extraordinary gentlemen, selected as if bespokedly to fit exactly my own life of computer-game passions. Wasteland, Fallout, Mask of the Betrayer, Planescape: Torment . . . . Short of shang-hai'ing the Gollop Brothers, Paul Reiche, and Fred Ford, it's hard to imagine how it could get much better.

Now, "this" might also mean the experience of the night itself. You know how people ask, "If you could have dinner with any five people, who would they be?" Then imagine you invite them over to dinner, and Abraham Lincoln has an oozing hole in his head and he keeps going on and on about his fucking Marfan Syndrome, and Mark Twain says, "Pull my finger" and is just farting the whole damn time. Or, probably, they'd all just rather talk to each other than to you, because, seriously, is there any chance -- ANY CHANCE! -- that you would be on the magical dinner list of any of those people? Fuck no.

So when you assemble all your game-making idols in one place, isn't there a very real risk of discovering that they're a bunch of jerks, or that they think you're a loser to be treated at best with transparent condescension and even that courtesy only because they mistakenly think that you, personally, backed Wasteland 2 for $10,000 when in fact you haven't even bought the game because you refuse to pay more than $10 for anything because we live in a golden age of cheap media?

Very real, indeed.

But, it turns out, my neurotic fears were totally misplaced. Despite (or perhaps because of) looking like Ming the Merciless, Colin McComb has a gentle, erudite friendliness and a willingness to be teased by a loser like me that seem out of place for man who could create such an abomination as the bladesinger.* Avellone -- too cool, I think, to be the tortured soul I imagined when playing Torment -- took my idolatry in good stride, and we traded stories of youthful excess. George Ziets and I talked about emotions that games seldom touch upon -- melancholy, ennui. I groused to him and Kevin Saunders about the stupid Venetian Carnival mask I had to wear in MOTB to boost my charisma; when I lavished them with praise for their intelligent use of transitional text in loading screens, they drilled down into other non-traditional mechanisms for conveying story.

It's hard -- in part because I wasn't taking notes, in part because in my own mind it's all a gestalt -- to try and recount every bon mot and clever design trick they dished out. It's easier to talk about things at a high level, and from that vantage, three things stand out like the Great Wall (which is not the only man-made object visible from space, but it's a useful trope; try using more than 10% of your brains!):

(1) These guys really think hard about games and how to tell stories through games. I've been privileged to talk with people at a fair number of game companies about story-telling, and while everyone aims high and does their level best, there was a difference in kind between the inXile / Obsidian crowd and people I've spoken to before.

Specifically, there sometimes seems to be a gap in the passion and attention that gamers pay to games and the passion and attention that game-creators pay to games. This, to me, is why the Codex -- despite its many faults (or perhaps because of them) -- is so important: the level of analysis that the Codex has been doing for over a decade is unparalleled (Emily Short's interactive-storytelling analysis is too different to compare, but equally important). Ordinarily, if you try to engage a game-creator at that level of discussion, it's impossible. Not so with these guys. Far from responding with glassy-eyed bemusement, they gave better than they got.

(2) They are passionate about story-telling in a broader sense, which means they are avid readers, watchers, players, and they engage in this consumption with a critical eye. While I don't read or watch or play as much as I used to, I'm accustomed to being able to name-drop obscure works to outflank my interlocutors; here, however, I found the inXile folks were already familiar with almost everything I whipped out. (It was quite delightful to meet people who also admire Barbarian Prince.)

(3) They're nice guys. This was supposed to be their night, where -- among friends -- they would let their hair down (Colin excepted) and celebrate the fruit of months of sweat, toil, and tears. Instead, they spent it entertaining a handful of geeky randos.

It would have been easy -- and appropriate, even -- to seat us at a kids' table, stop by, slap some backs, shake some hands, buy a round of drinks, and then go back to the grown-ups' table. But that's not at all what they did. To the contrary. At one point midway through the night, I found myself retreating awkwardly into a corner like a middleschooler at a dance party, not comfortable intruding further, especially since everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves. Colin found me, grabbed me, said, "Hey, there's some more guys I bet you'd like to meet," and sat me down among another friendly group.

The fact that they seemed genuinely excited to meet the backers speaks volumes. Unlike Fargo, who as a businessman may well have been capable of poker-facing his way through the whole night, these guys did not seem willing or able to engage in that kind of glad-handing. Rather, despite years of grizzling, they still had the bloom of new creators who are delighted and surprised that people could be so interested in their creations, and flattered by the attention (and generosity) their fans had shown them.

Earlier, I said that Fargo made me realize how young the industry is. But in fact, the inXile crowd exuded thoughtful maturity as much as youthful enthusiasm. At one point I told them that my biggest fear for Torment: Tides of Numenera was that it would capture PS:T's essence and yet not engage me, and that as a result I would conclude that I had fallen in love with PS:T not because it was "objectively great" (whatever that might mean) but because the themes that seemed so well developed were in fact little more than sophomoric musings on adolescent passions, perfect for a self-absorbed 19 year old. (I was a little less pretentious in saying it than I have been in writing it.)

Their response was measured and careful. In essence, I was told not to forget that decades have passed, and that the folks making T:TON are not the same people they were when they worked on (or fell in love with) PS:T. Loss, suffering, and change mean different things to a middle-ager than they did to a young adult.

Embedded in this answer was something that gave me great hope: the premise that the team was attempting to convey the living spirit of PS:T that still moved inside them rather than -- like John Hammond -- trying to extract the dead DNA frozen in the amber of the old game itself. Put otherwise, they seemed to say they were exploring themes that matter to them now, not themes that mattered to other players years and years ago.

I say that it gave me great hope, but it causes me some nervousness, too. Sometimes creators love their creations for the wrong reasons and, if left to their own devices, try to beautify things with the crudest of plastic surgeries. (This was Newport Beach, after all.) And we've all seen one nightmare after another emerge from the dream of modernizing the classics while "capturing the spirit of the original."

Still, what I think we all loved in PS:T was the way it felt like a personal game, not the creation of a corporate focus-group. And, for all their successes -- for all they were celebrating in the most corporate-focus-group-ish of venues -- I cannot imagine this team succumbing to the urge to pander.

* * *

I drove home on long, dark, empty freeways with plenty of time to think about the people I'd met at the party. It is exactly in such circumstances that my cynicism swells to fill the emptiness around me. Was Fargo just a salesman? Were the backers just being treated like mascots by the cool kids? Had I gone all that way for nothing?

But, for once, these doubts crawled away of their own accord. Rabbi Heschel says of the "self-suspicious man" that, "living in fear, he thinks that ambush is the normal dwelling-place of all men." But that isn't where most men live. Not all dreams turn to nightmares; not all friendliness is smarm.

For once, for now, I'll believe that things really are as good as they seem at inXile, and I will merely . . .

-----------

(* True story: While at nerd camp as a kid, I played AD&D for the first time, and wound up DMing. One of the other nerds had brought a bladesinger character sheet from home, and as I read over his abilities, I was incredulous. No fucking way that's how the rules work. Dude has to be lying. But he whined and wheedled, and who really cares, I can just throw mithril-armed super-orcs at him. I had largely forgotten about this incident until Colin made his YouTube apology, and I discovered that he had managed to design a class so stupid that even someone who knew nothing about AD&D rules could tell it was broken. When I needled him about this, he replied, "You don't have to worry, I'm not doing any balance work on Torment.")

There are 91 comments on RPG Codex Report: Wasteland 2 Release Party