Have you ever heard of this old game called

Potty Pigeon? It was a juvenile game where you controlled a pigeon and had him drop bird poo on cars. That happened, and it got a few ports. You can probably find some equally immature versions around made by flash developers for browsers, knowing the internet. Now you would expect the bird pooping simulator genre would have disappeared as soon as it began, and for the most part, you would be right. But then in 2016, Russian indie dev WolfgangIs released

Grand Pigeon’s Duty, a new entry in the bizarre sub-genre that not only managed to somehow be good, but also managed to be so wildly different from anything ever seen before that it defies normal categorization.

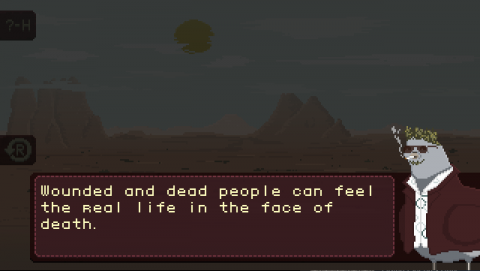

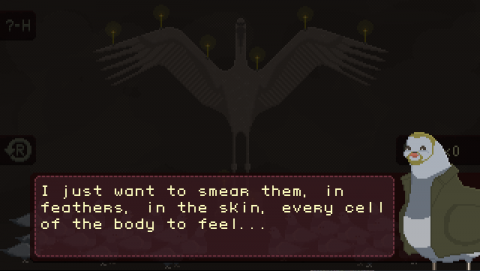

You know you’re in for something different when the menu includes a button that shows a message for English players where the developer apologizes for his poor translation done entirely by himself, and then goes on to explain how he tried to capture the simplistic logic he believes pigeons would think and talk with. Starting the game proper further catches you off guard, as a long text crawl explains that humanity have become a race of gas powered cyborgs that no longer need bread, causing pigeons to starve since nobody is feeding them bread crumbs anymore. Your character, John, has a dietary disease that causes him to poop far more than normal, which becomes the resistance’s main method of getting attention for their plight. At one point, you reach a decision that can branch you off into three different story lines, one with the resistance, one with your brother and the head of the oppressive Bread Bank, and one where you help carry out terrorism with the Tyler Durden bird.

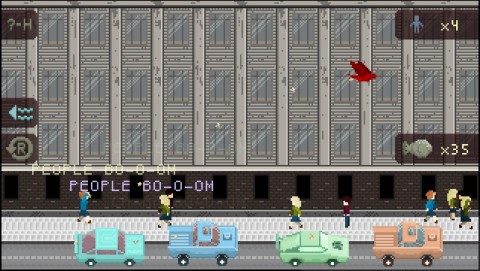

Yes, there is a Tyler Durden bird. There’s a lot of pop culture references in this game …and somehow, most of them are thematically appropriate for the surprisingly involved story that explores class divides, social economics, revolutionary ethics, and the extent of family bonds. In the game where you poop on people and watch them run away with poop on their face. There are entire subplots about corrupt banking systems, committing public demonstrations to send political messages, revenge killings, and religious redemption. There are characters that represent ideologies of excess, survival, and charity, and endings that revolve around making moral choices based entirely around your reactions to the ideals your allies have shown you. Once again, none of this is made up. This is all in the game, and it is not subtle about it.

Characters will have long dialog sequences between missions where they talk about their world views and how they became who they are, and it’s all well thought out, even taking into account the relationship between the birds and humans. For example, your brother Claus has a weight problem and failed at everything he tried, but a human millionaire found him amusing and took him as a pet, pampering him to keep him chubby. The end result is a fun loving hedonist who will occasionally edge you on to ruin other people’s good times out of spite as he hogs the world’s only remaining supply of bread. Most major character have believable back stories like this, and a firm conviction in their ideology and ethics. It’s genuinely interesting to read, even with the messy translation. Someone made a game about birds pooping on people and put in a narrative more thoughtful than the large majority of AAA games do. It must be said again that none of this is made up. Of course the game shows it has a sense of humor about itself quite a bit, particularly with the few scenes with the Tommy Wiseau bird (because of course there’s a Tommy Wiseau bird), but it never lets self-awareness drown out the effective drama.

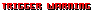

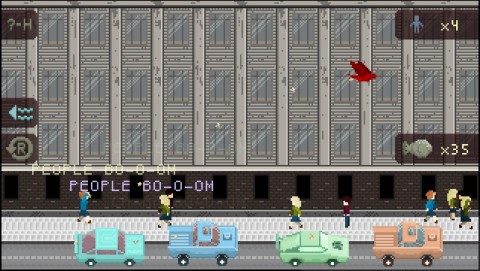

Grand Pigeon’s Duty has narrative chops, but it also has gameplay chops as well. Every mission has a different challenge, sometimes pooping only on cars, sometimes only people, and sometimes planting explosives on a train, pooping on a bunch of rich birds into scat, or trying to cook a potion that will grow massive bread. This is a game with variety, and when it doesn’t have that, it has challenge. Most every mission gives you very limited ammunition, so you have to make every poop carefully, especially on the tiny, moving human targets. It gets even more complicated once wind is introduced, blowing either right or left and requiring better timing to successfully hit a target. The game can easily take up to four hours to beat just due to how difficult some missions get, despite a perfect run taking only a few seconds. It also becomes incredibly frustrating, as it is common to be stuck butting your head against a brick wall of a mission before you manage to magically complete it. Before then, expect cursing from having just one badly timed poop. Hitting people is especially frustrating, your best chance sometimes is just focusing on cars if they’re apart of the goal and hope people walk into your poops. If cars aren’t part of the goal, prepare for failure. Thankfully, restarting a mission is as easy a pressing R, and there’s no loading for it.

To make the story even more engaging, little change ups on some missions pop up. They make the game stick out and make it something special, almost always connected closely to the main plot. One mission where you poop on a journalist over and over is a means to try and send a message to get him to write about pigeons. The out of nowhere formula cooking minigame in the Tyler Durdan bird branch is an exercise in symbol reading to make out a recipe. The pooping on an entire religious order for Claus is the first major moment that reveals Claus’ true nature. Even traveling in some air vent tunnels to reach a kitchen involves having conversations with a crazy rat king who has eaten some of your friends but feels bad about it, going on about how he has gone mad from being lost in the maze. He’ll thank you if you find the exit, and even become friends with the resistance after. There’s always a reason for these strange moments, and it makes the story more engaging. It’s sort of like this game combines elements of visual novels and …uh,

Potty Pigeon. And it works.

The sprite work isn’t moving fine art like you’d find in

Owlboy, but it’s by no means poor either. There’s overlap in pigeon body types, but it’s offset by their wildly different clothing and colors. The vistas in every stage and during dialog scenes are incredibly detailed, with individual bricks and cracks. There’s a great use of contrast between color tones, making a lot of what you see pop just enough to make you notice the details. The animation is also smooth, really shown off during the ending fight in the Tyler Durdan bird route where you both become giant monsters and fight to the death (long story). While a good impact sound effect is missing, the whole screen shakes when you land, really making you feel your weight. There’s even cute additions like little exclamations coming from successful hits, especially rewarding when you finally nail someone in the face. The music is also quite catchy and may even stick in your mind a bit after playing, especially with as often as you’ll be playing certain parts over and over. Despite the absurd premise,

Grand Pigeon’s Duty takes itself quite seriously, and so much care was poured into every aspect of it.

The game is less than five bucks to get on Steam, and it’s so polished and filled with passion that it’s hard to believe it’s not priced higher. This is the sort of game that makes the indie gaming scene something special. Anyone can build on the foundation of the classics, but building on the foundation of a joke game about pooping on cars until they crash and including political commentary with real complexity and depth in the process is something you would never see anywhere else. We should be glad this ridiculous game exists, because we need the ridiculous to push the boundaries of what this medium is sometimes.

Grand Pigeon’s Duty doesn’t necessarily do that, but it certainly is unlike anything else you’ve ever played.