How Kenshi's world is designed not to care about you

Tough love

The Mechanic, where Alex Wiltshire invites developers to discuss the difficult journeys they’ve taken to make their games. This time,

Kenshi [

official site].

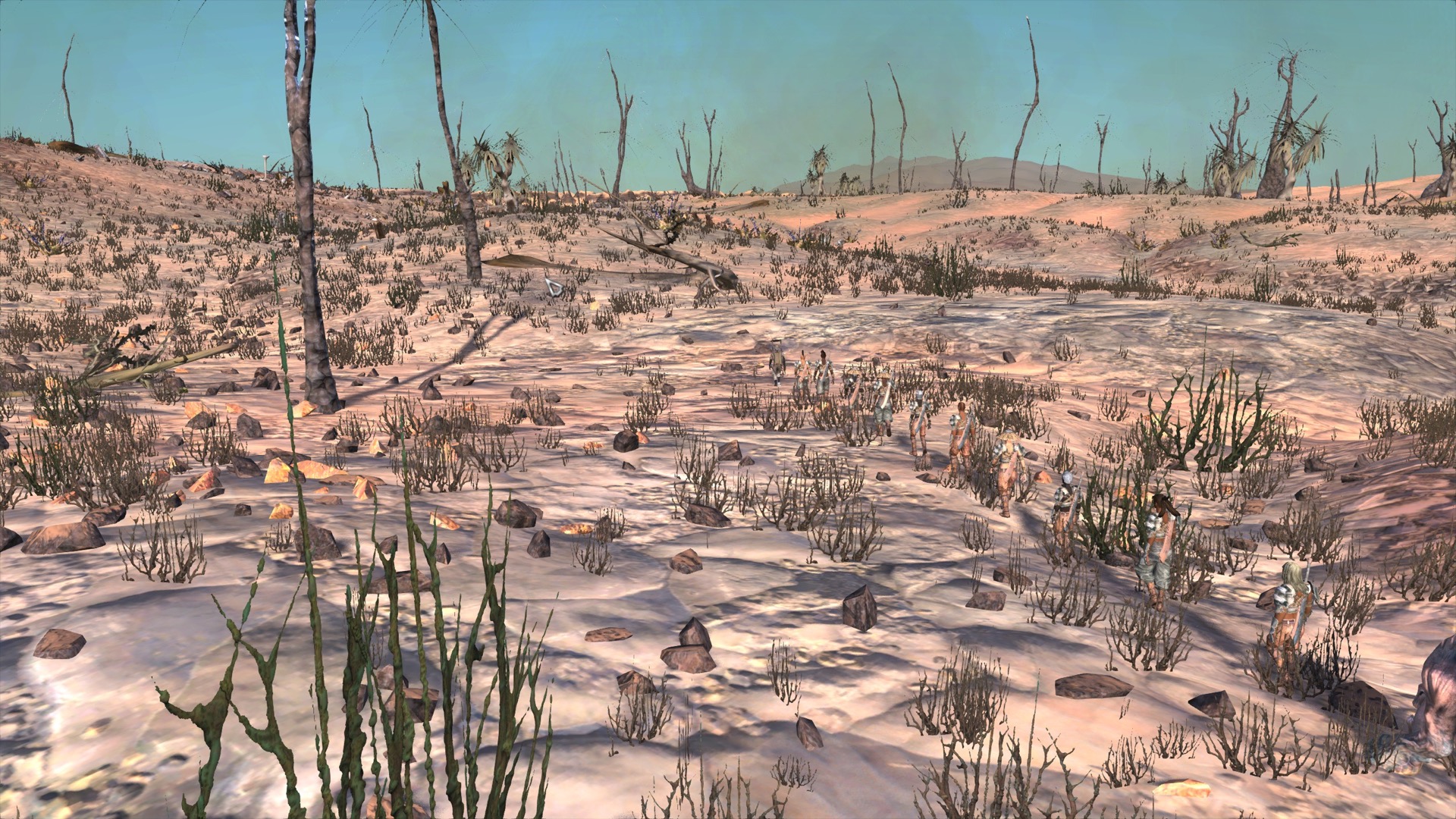

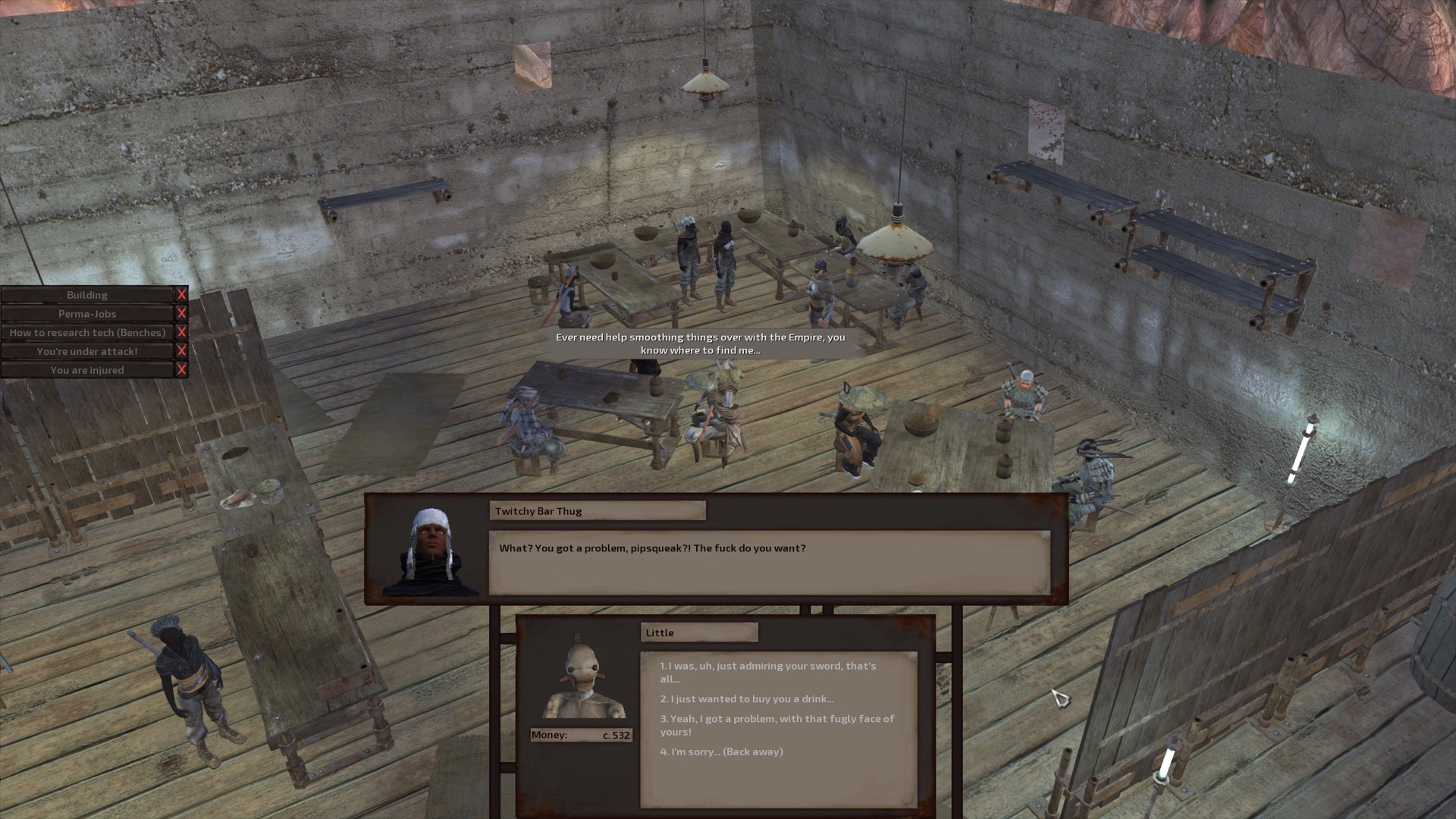

You’re not the hero in Kenshi. You’re not the chosen one. There’s nothing out there for you to save – other than your own skin. You’re just another inhabitant of a huge open world that doesn’t care about you. That’s its magic, and it takes design to create a world so exquisitely uncaring.

Merry Christmas, everybody!

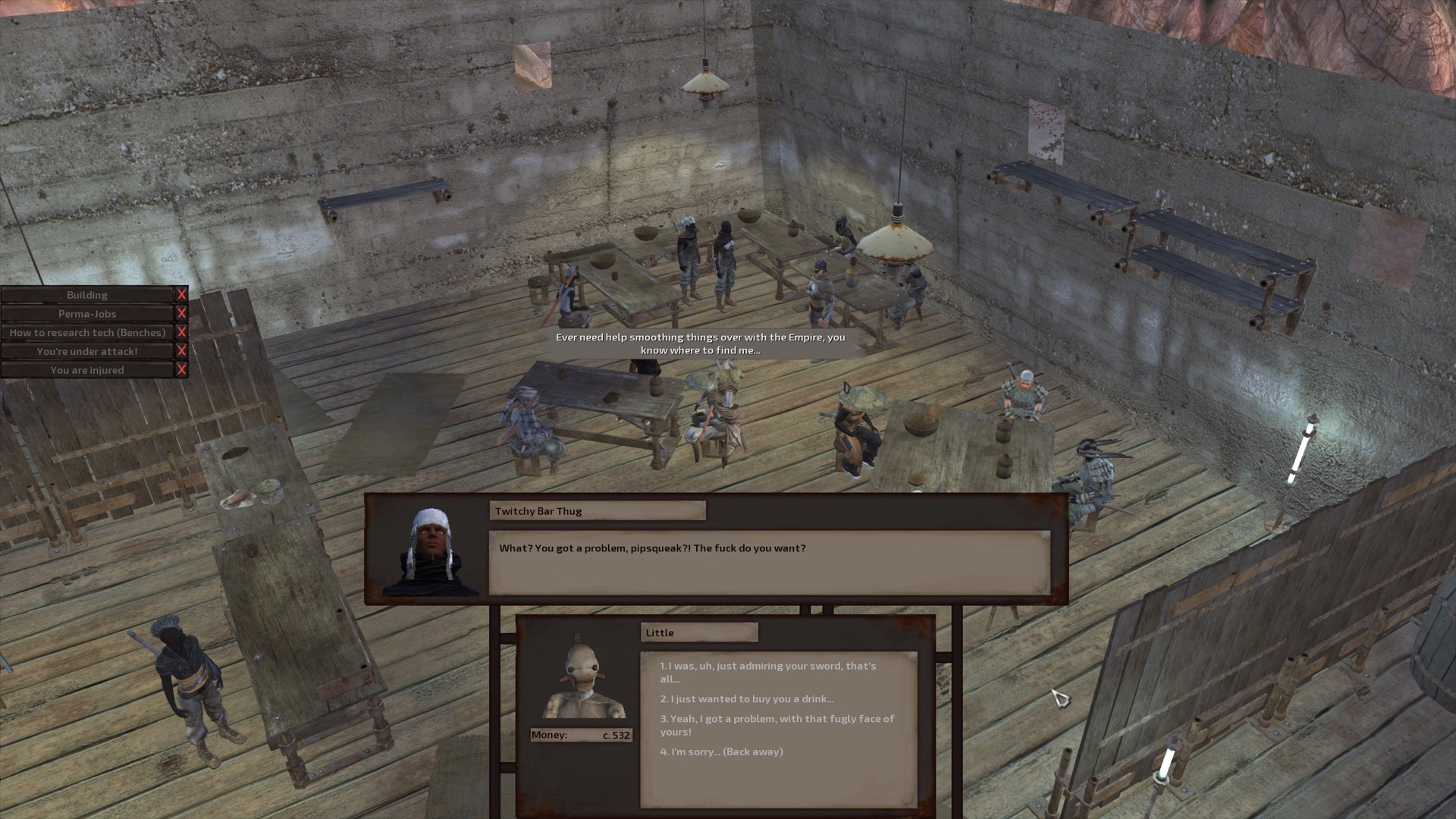

Put it this way. Designer Chris Hunt, who’s been making Kenshi for some 12 years, has wondered about making a character come to a player at the beginning of their game and call them the chosen one. “Then he’d use that to fleece some money out of you and then run away or something.”

Thankfully, he hasn’t gotten around to adding it, but his sister, Natalie Hunt, did add a similar player-taunting detail that underscores the uncaring nature of this vast and demanding RPG. Go and speak to the emperor of the largest faction, the United Cities, and he’ll appear to give you a quest. “In reality, you’d probably be arrested for walking up to an emperor,” says Hunt. “So he gives you made-up quest and all the characters in the room start laughing at you. I’ve seen forum posts where people didn’t quite get it and ask how to finish the quest, going to the far end of the desert to find some wizard with a stupid name.”

Kenshi, after all, has no quests, just the ones you set yourself as you carve out a place for yourself within its world as a trader, a farmer, a raider, a thief, or a leader of a settlement of your own. Whatever you choose to do in Kenshi, it’s driven by the design of the world itself.

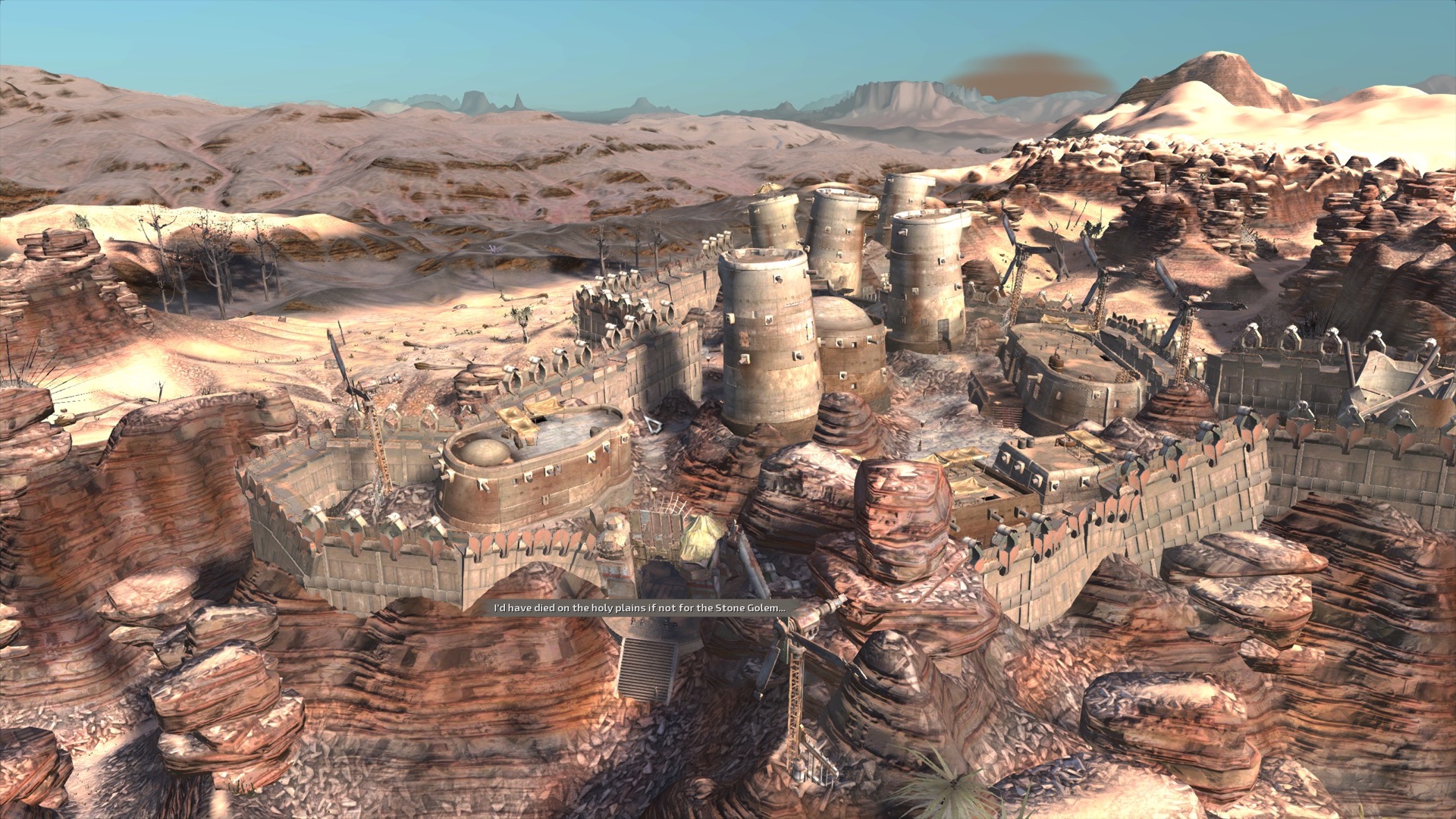

But even though the world is simulated, everything within it is hand-placed, whether it’s a town, the loot in a tower, the weather, animals and vegetation, mining spots, fertile ground, NPCs and the contents of shops. Filling a world of 870 square kilometres with things to do and interact with was, Hunt says, the hardest thing about developing the game.

“The whole thing is one consistent long battle of complexity so I never really stopped at it, I guess. The size overcomplicates anything and everything you do,” he says. But Kenshi had to be big. “I like the feeling of exploring and ending up in different lands. There aren’t many games that really do that. You know if you go to some island in Asia, you can stand there and feel you’re miles away from anything you know? I wanted to have a game where you can feel you’re in a far-away alien place.”

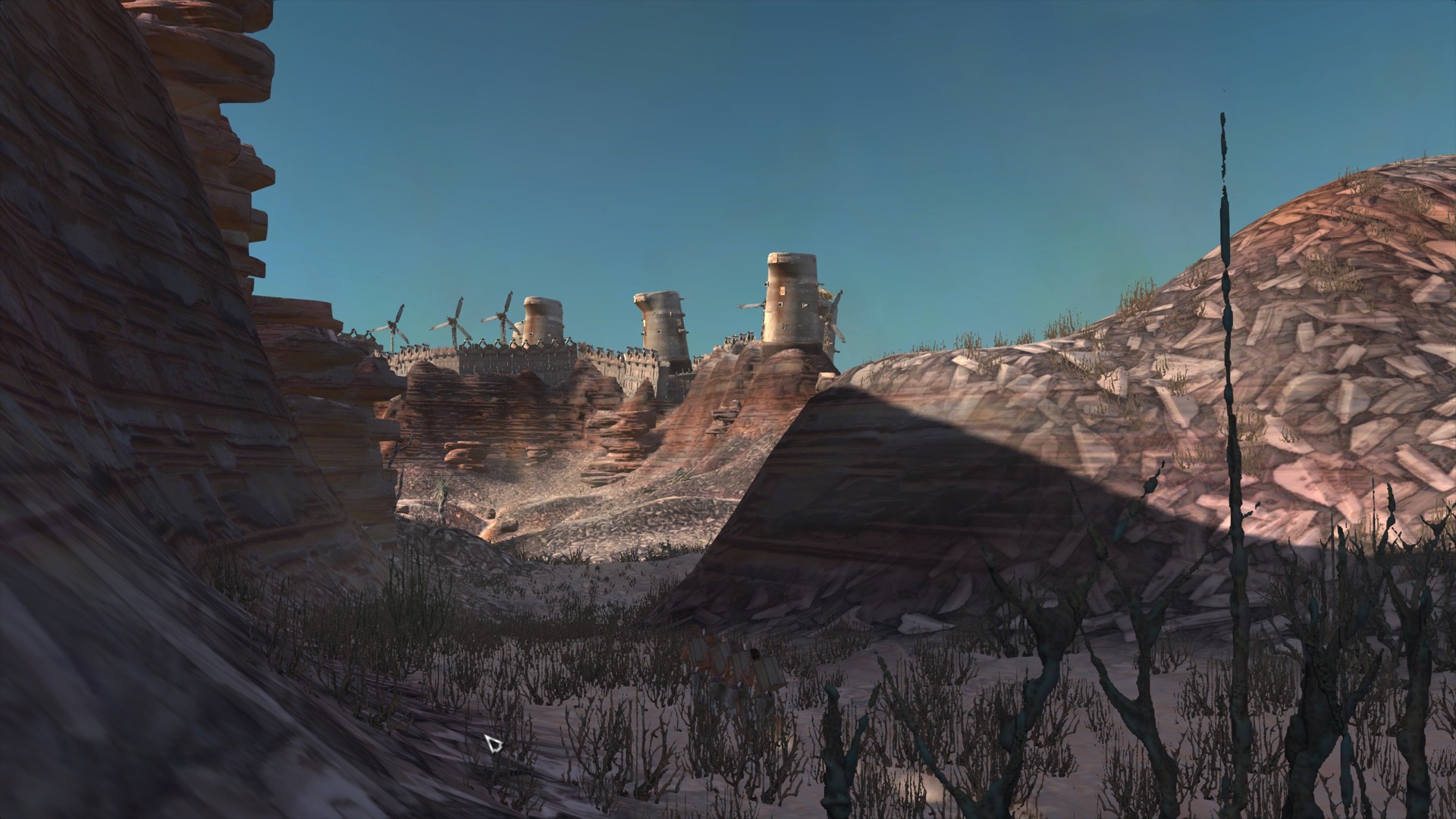

Kenshi’s often harsh topography, created by artist Oli Hatton, reflects that idea. He used terrain generators to build sections before going in to hand-edit and then fold them into the rest of the world to produce a shifting and often-desolate landscape. It’s often strange in form, capturing the alien nature that Hunt wanted, but he also wanted a sense of realism, with erosion and other naturalistic features.

And then they had to fill it with interesting stuff. “There’s no point in travelling for miles and miles across the map if everything’s the same,” says Hunt, so he avoided evenly distributing things. He split the world up into some 60 different biomes, geographical areas distinguished by certain NPC cultures, weather, topography and other factors. But, often working entirely on his own, and with a team that never exceeded six members, he only had a limited stock of different items.

”Basically I just stare at an image of the map for hours and hours and try to think about how it’d work,” says Hunt. In many ways, creating the world was like solving a huge, interlocking puzzle, fitting together each area so they provide the uneven scatter of culture he wanted while also being good to play in. Kenshi might seem not to care about you, but it’s still entirely designed

for you.

“You want a zone full of treasure to be in the far reaches, you don’t want it to be easily accessible,” he explains. “And maybe you want some dangerous inhabited zones in between, and you have to think about how they work together. What’s blocking access to another zone? Where are the main hangout areas, the easy areas, the difficult areas, the exploration zone?”

So Hunt partly thinks about Kenshi’s world in terms of the journeys players take through it. “I always saw designing the map as laying traps for the player,” he says. “I consider myself the player’s enemy. I set traps and things that can go wrong. Sometimes I like to try to deceive the player.”

His main tool is player expectation. “If you can subvert it in a fun way, then you’ve got yourself a fun trap.” One such trap is a tower, one of many that players will have learned hold lots of technology and treasure. In this trap tower, however, players will find a trail of semi-valuable items going up the stairs, and when they arrive at the top they’ll find a hundred cannibals and nothing else.

Some of those journeys are trading routes. One such is between the lawless Swamp, where you can buy extremely cheap locally grown hashish, and the Great Desert in the north-east where the United Cities is based. Hashish is illegal there, but if you can cross half the map, braving all the threats on the way without starving (you won’t be able to grow anything since the lands you tread are pretty much totally infertile),

and you can get your contraband past city guards, you’ll make a 2000% markup.

Hunt also had to think about the journeys that the AIs take. You don’t directly control your characters in Kenshi – RTS-style, you click on the landscape or map and they’ll navigate there themselves. ”Sometimes Oli would make big impassible mountain ranges and I’d have to make him break them up a bit so we could put some paths through that the AI could handle,” Hunt says.

These paths aren’t necessarily visible roads. They’re for the AI, the result of a problem Hunt encountered with pathfinding in such a large space. The game only loads nine ‘zones’ around the location of the camera, simulating everything that happens in them. As you move the camera around, the game loads in the next three zones in the direction you travel, and unloads the three behind. But you might send a character out of these zones. Since the game doesn’t have terrain in memory, it can’t pathfind. “So we had to make this abstract global system of roads,” says Hunt. They’re like AI motorways that help it get around when the world doesn’t exist.

As well as journeys, Hunt also thinks about the world in terms of stories. He wanted parts of it to hold hints to its history, such as a crater which may have been the site of a meteor landing, or where a bomb exploded. The details are never fully explained – Hunt is not a fan of exposition – but they might be alluded to in the game’s sparse lines of NPC dialogue, adding layers of new context which it’s up to the player to put together.

Like so much of Kenshi, these features aren’t evenly spread across the world. “Sometimes the entire feature of a zone might be that it’s empty, desolate and lifeless,” says Hunt. Or it could be the local weather or the kind of NPCs that live there. “We’ve tried to lay everything out logically, based on the story and the physics that’d occur. So you’ve got a volcano zone, where the water is acidic and there’s continually falling ash. There’s another zone that’s a desert with harsh storms in it. We try to connect everything up.”

The way the culture of the different factions is reflected in the items shops stock is a good example of this relationship between story and world design. In the Shek kingdom, a faction of tall warriors, you’ll only find large weapons. Because that’s what they’d stock, and if you want something smaller, well, tough. Likewise, in the Fog Islands where the cannibalistic Fogmen live, who capture their victims and eat their legs (Kenshi has a detailed body damage system), you can find a shop which sells the very best robotic limbs, if you can get to it.

Shop goods was an important part of designing Kenshi’s world, because they do so much to push players out into the world, and Hunt’s philosophy was guided by what he doesn’t like in other games. “One of the worst things games do nowadays is base the contents in shops on the player’s level,” he says. “So you’re level two and see nothing but level two leather armour and iron swords. There’s no choice. The best part of shopping is to look at the fancy stuff you can’t afford and wish you could and get excited. It gives you the drive to earn money and do something in the game.”

Kenshi looks like it doesn’t care about you when the shops don’t have what you need, forcing you to go to places that might not be good for you. “Personally, I think it’s fun to venture into an area, realise you’re in over your head, panic and flee,” says Hunt. And it looks like it doesn’t care about you when you’re stuck in the middle of nowhere, with no access to water and food. “If you’re somewhere there isn’t what you need to equip to survive, then that’s your own fault, it’s part of the game.”

But in truth, this harshness, this shove to be part of and make the best of Kenshi’s world, it’s

all about you.