-

Welcome to rpgcodex.net, a site dedicated to discussing computer based role-playing games in a free and open fashion. We're less strict than other forums, but please refer to the rules.

"This message is awaiting moderator approval": All new users must pass through our moderation queue before they will be able to post normally. Until your account has "passed" your posts will only be visible to yourself (and moderators) until they are approved. Give us a week to get around to approving / deleting / ignoring your mundane opinion on crap before hassling us about it. Once you have passed the moderation period (think of it as a test), you will be able to post normally, just like all the other retards.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

KickStarter Kickstarter Watch.

- Thread starter Kz3r0

- Start date

kaizoku

Arcane

- Joined

- Feb 18, 2006

- Messages

- 4,129

kaizoku

Arcane

- Joined

- Feb 18, 2006

- Messages

- 4,129

slim version of the occulus rift

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/avegantglyph/a-mobile-personal-theater-with-built-in-premium-au

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/avegantglyph/a-mobile-personal-theater-with-built-in-premium-au

Kz3r0

Arcane

- Joined

- May 28, 2008

- Messages

- 27,026

Racing Games

Carmageddon: Reincarnation A piece of Videogame history returns.

Distance - A Next Generation Arcade Racer From the creators of Nitronic Rush.

nstaCharge Futuristic motorcycle racing game based on a short animation movie of the same name.

Road Redemption The new Road Rash.

MotorGun - Return of the Auto Duel A new vehicular combat game from a team that includes the creative minds behind Twisted Metal and Interstate ‘76.

Distance - A Next Generation Arcade Racer From the creators of Nitronic Rush.

nstaCharge Futuristic motorcycle racing game based on a short animation movie of the same name.

Road Redemption The new Road Rash.

MotorGun - Return of the Auto Duel A new vehicular combat game from a team that includes the creative minds behind Twisted Metal and Interstate ‘76.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 100,805

Kz3r0 http://extralives.wordpress.com/2014/02/08/kickstarter-experienced-teamsindies-and-new/

KICKSTARTER – EXPERIENCED TEAMS/INDIES AND NEW

February 8, 2014 · by Reggie C. · in On Gaming. ·

(Full disclosure – I have backed Kickstarter projects. The data for the following article is based on UnSubject’s original data. My worksheet with the new variables and my final numbers is located separately here.)

Author UnSubject over at his blog, Evil As A Hobby, scrubbed through video game labeled Kickstarters spanning 2009 – 2012 and assembled the data into a compelling look at the extremely low rate of follow-through made by over 366 projects. It’s a great article that has encouraged quite a bit of discussion both there and across the ‘net.

It’s a revealing look at something that I could only touch on in the end summary to mysurvey of 2014′s gaming landscape on Gamesbeat – a disturbing implication of completely missing release estimates by Kickstarted projects based on only a tiny sample of reported releases slated for 2014. UnSubject’s exhaustive work not only nails home what I could only assume, but encourages discussion on just how successful hundreds of other projects have been in the past few years as part of a bigger picture. It’s an eye opening read.

UnSubject has also made the data available for everyone to look through and being interested in crowdfunding, particularly the ramifications of what Kickstarter and Steam’s Early Access have created for developers, I took the opportunity to scrub through it myself to answer a question posted in a comment to the original article linked to their blog above: does experience matter?

It’s no secret that experienced game developers, both indie and commercial, have used Kickstarter in the past and are continuing to do so today. But how well have they actually fared against teams or indies with little to no game development experience?

Definitions

The first problem was in defining what that experience was.

Because gaming is still relatively young as a creative medium, terminology hasn’t quite developed at the same pace (just look at the debates over RPG definitions). I didn’t like having to use the term “inexperienced” which I felt has too much of a negative connotation to it. Instead, I’ve opted to define such teams or individuals as being new to development.

The next problem was just what that experience entailed. Is it having made one flash game? Or is it having made a dozen over the years for free? Does commercial success make a person experienced over a team of a fans that can code a game from scratch as a tribute to a classic title? Is it the resume-defined version of having X number of years and Y shipped titles?

The definition of experience that I used started with the following conditions:

Individuals/teams were automatically considered ‘experienced’ if they had the following:

- the developer has to have created and made available a complete game to the public; medium doesn’t matter aside from it being a video game of some kind

- said game has had to have been recognized by the public (such as being recognized at the IGF Awards or by a major outlet such as Gamasutra, Gamespot, etc.. or through popular acclaim) or has been made commercially available

The reason I had stuck to these set of requirements was to filter out situations where an individual may have created one Flash game years ago that no one had ever heard about.

- if the individual(s) has had experience at a major game studio

- if the individual(s) have aided or have produced a commercially available title

- if the individual(s) has had a long career in a field related to game development (such as having been a coder for several years)

If a Kickstarter had also claimed experience, I also had to be able to independently verify that experience using the information given to me in the same pitch that everyone else will be reading. If I couldn’t verify it, I couldn’t count the project.

I’ll be the first to admit that this isn’t a perfect definition. There were one or two projects over which I was not sure whether to mark them as experienced. It had also raised a number of important issues that I’ll touch on towards the end.

With that said, let’s take a look at what I could pull from UnSubject’s meticulous research to answer the question of just how much experience factors into their Kickstarter project data.

How many Projects

Based on the premise of UnSubject’s data, we’re looking strictly at successfully funded Kickstarter projects spanning 2009 on through 2012 for a total of 366 projects.

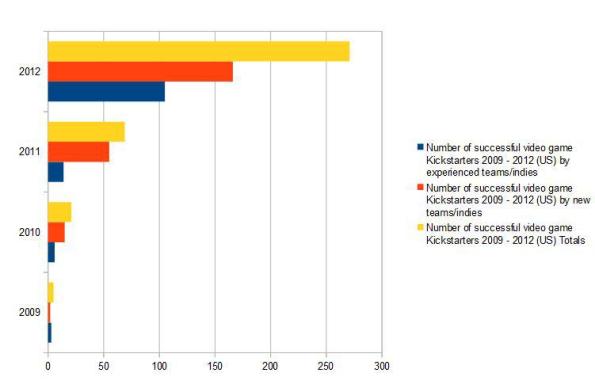

The chart above separates the projects into three categories per year. The yellow bar indicates the total projects, the orange shows the number of those that were launched by new indies/teams, and the dark blue stands for projects by the experienced teams/indies.

The actual numbers look like this:

Given Kickstarter’s initiative as an crowd funding enabler for new teams and independent projects, this shouldn’t be too surprising to see such projects outnumber the “veterans” with 2009 as something of an exception.

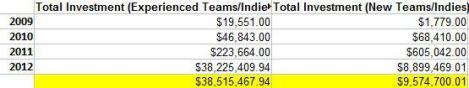

Cash flow tells an interesting story:

Teams boasting some experience or popularity based on their previous work still pulled in a respectable share of donations with new teams/indies beating them in 2010 and 2011, likely because they had the most projects for backers to throw more money at. In 2011, 14 funded projects were launched by experienced teams competing against 55 launched by those without experience, for example.

But 2012 saw a major money shift. That’s arguably thanks to the focus on the massive success of Double Fine’s project and the Ouya Kickstarter later in the year.

At the same time, the argument could also be made that seasoned teams would still have found the same degree of success given time. This is borne out by sixteen experienced projects posting over 500k in donations following Double Fine’s. Even if we took out Ouya’s and Double Fine’s Kickstarter numbers, experienced teams/indies still had drawn in roughly 3x as much cash versus those just starting out.

Ultimately, successful Kickstarters by experienced indies/teams saw a nearly tenfold increase to a total of 105 such projects in 2012 versus only 14 in 2011.

Also interesting were how many projects allowed for external funding options, such as Paypal. Out of all of the experienced projects, 22 opted to support that initiative versus 15 for new devs.

Completionist

So how do Kickstarters seasoned with experienced individuals fare against those just starting out? Let’s take a look at what the charts say in looking at the total number of funded projects by both camps spanning 2009 on through 2012:

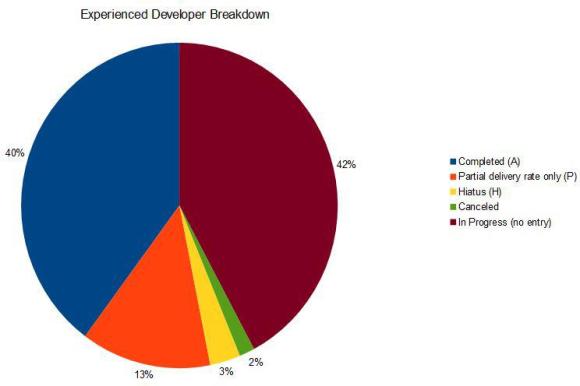

Kickstarters with experienced teams/indies broke down into the categories you see in the above chart using UnSubject’s data sorting and then applied to the question I filtered those results through.

For example, here we’re seeing that, to date, only 40% of those projects with experience have been completed. On the other side of the coin, 13% have been released in a partial state which can include Early Access on Steam, an ongoing “beta”, or as “Part One” with subsequent releases to arrive later.

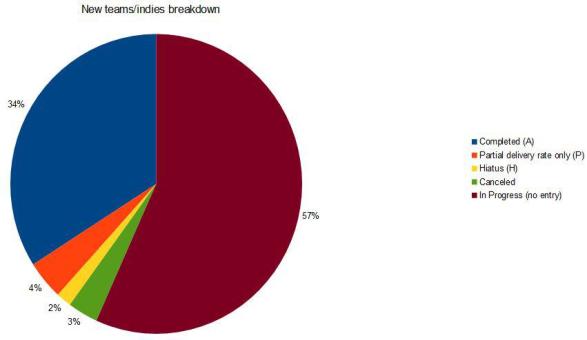

Compare the results above with projects that from devs just starting out:

Highlights include seeing only 34% of those projects launched by new teams/indies having been completed to date. A whopping 57% are still in progress.

What’s interesting, however, is that only 4% of these projects have released a “partial” game in lieu of a complete one versus the 13% in the experienced camp.

The charts appear to indicate that veteran developers have the edge in completed projects, or at least in releasing partials to satisfy backers and garner additional income via initiatives like Early Access. But breaking down the numbers is a bit more revealing.

For one, new teams/indies have the lion’s share of projects on Kickstarter resulting in higher numbers in nearly everything else as noted earlier in the bar graph above. Let’s take a look at a few of the numbers bearing this out:

So while the percentages skew things towards experienced devs, the actual numbers can argue that newcomers are busy on a much larger range of projects with more releases.

- Compared to the 128 that belong to the experienced camp, new developers have launched 238 projects.

- For the 51 projects that experienced teams have technically completed, those starting out have 81 in the same category.

- Experienced teams have 54 projects that are still in progress versus new developers who are busy working on 135.

First Impressions

Before finishing with a few final thoughts, a few words on building a Kickstarter pitch.

A common theme for both camps is that regardless of experience, creating effective pitches continues to be a problem for both.

There is a disturbing undercurrent involving claims for experience yet making it inordinately difficult to actually perform any due diligence. I’m not asking for specifics like an actual resume, but if you have work that you’re proud of, let the world know and make it easy for potential backers to find. For me, simply claiming that “we’re experienced’ and leaving nothing to back that up is a huge red flag. If your team can’t be bothered to go that far, why should your backers with their wallets?

Backers also have to be told where they can find the latest information and be kept in the loop. If you’re moving your updates to a site that is being set up specifically for your game, make sure you let everyone know so that they don’t believe your project has died. If you can’t do that, or make the information difficult for anyone to find, backers are going to get pissed.

In other words, communication is key. Sometimes, all it takes is a name to get an idea of what to expect. Treat your audience like adults and don’t skimp on the information. After all, you’re asking a worldwide audience to take a chance on you. Put your best effort out there.

Conclusions

So does experience matter?

The data presents a compelling argument that it brings a certain level of professionalism enabling, at least percentage-wise, more projects to completion or partial release although the breakdown paints a more nuanced picture. I can’t speak to the quality of the final products, but it’s safe to guess that an element of that experience is in knowing how to build an efficient production pipeline process right from the start. There is also the factor of being able to work with fellow developers that may have shared similar working experiences over many years.

Projects that have had professional artists, not necessarily game developers, as part of their push have also often had the most impressive looking pitches. That should probably be no surprise, yet at the same time, the lack in mentioning other disciplines such as programmers, hard designers, managers, etc.. that normally would accompany such a project is pause for thought.

Scrubbing through the projects myself also affirms the notion that having experience isn’t necessarily a guarantor of success or product quality, especially when the results can wildly vary.

I’ll also re-iterate UnSubject’s warning – investing in Kickstarter is a risk.

If you can’t stomach the thought of potentially losing money on an investment, it’s probably not for you. Experienced and new developers have both canceled projects or have yet to deliver on their promises after several years of development as the above charts and UnSubject’s original findings bear out.

The biggest lesson for anyone thinking of investing in a Kickstarter project is in whether those launching the project have provided enough to go on, realizing the risk involved with the scale of their projects, and then choosing to invest accordingly…or wait things out. I still believe in Kickstarter as a valuable crowdfunding option for developers weighed with the understanding that it’s still a gamble, at least as far as release dates and the final quality of the project is concerned. But blind faith is no excuse for not doing your homework, no matter how much experience any one project may have on their resume.

Andyman Messiah

Mr. Ed-ucated

Kz3r0

Arcane

- Joined

- May 28, 2008

- Messages

- 27,026

Very long winded for saying something utterly banal, indies are more numerous so they score higher in every category, and he fails at statistics, for exactly that reason the fact that experienced developers have a better release percentage while unsurprising is very significative.

Drax

Arcane

Holy shit that's a lot of numbers.

Black

Arcane

- Joined

- May 8, 2007

- Messages

- 1,873,263

himmy

Arcane

Kz3r0

Arcane

- Joined

- May 28, 2008

- Messages

- 27,026

Added this one:

Kz3r0

Arcane

- Joined

- May 28, 2008

- Messages

- 27,026

Kz3r0

Arcane

- Joined

- May 28, 2008

- Messages

- 27,026

Kz3r0

Arcane

- Joined

- May 28, 2008

- Messages

- 27,026

Kz3r0

Arcane

- Joined

- May 28, 2008

- Messages

- 27,026

- Joined

- Jan 9, 2008

- Messages

- 1,864,630

![Glory to Codexia! [2012] Codex 2012](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_slushfund2012.png)

Is bundled before the kickstarter is even over.Savage: The Shards of Gosen:

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/561467528/savage-the-shard-of-gosen

Barbaric adventure with a dash of RPG! Explore and slay in a brutal open world — Conan meets Super Mario and Zelda 2!

...The mood and atmosphere are inspired by the Conan stories by Robert E. Howard, the Milton Bradley board game Hero Quest, and the Dungeons and Dragons setting, Dark Sun. Not to mention a healthy (unhealthy?) dose of my fetish for '80s barbarian flicks...

...The game features include a compelling combat system, item and skill progression, an open world to explore, and procedurally generated overworld encounters,...

Guy's asking for 6000 USD, has a playable alpha. Game looks promising.

Kz3r0

Arcane

- Joined

- May 28, 2008

- Messages

- 27,026

womensday.indiegogo.comCreate a crowdfunding campaign that empowers girls or women and Indiegogo will boost your efforts by matching $1 for every $25 raised on March 3rd.

Kz3r0

Arcane

- Joined

- May 28, 2008

- Messages

- 27,026

Last edited:

Kz3r0

Arcane

- Joined

- May 28, 2008

- Messages

- 27,026

Last edited:

kaizoku

Arcane

- Joined

- Feb 18, 2006

- Messages

- 4,129

https://www.kickstarter.com/project...ic-orchestral-recording-project?ref=discovery

George Oldziey is looking for game music fans from around the world to help fund an orchestral recording of music from Wing Commander.

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 100,805

https://www.kickstarter.com/project...ic-orchestral-recording-project?ref=discovery

George Oldziey is looking for game music fans from around the world to help fund an orchestral recording of music from Wing Commander.

One guy already did the main theme:

Kz3r0

Arcane

- Joined

- May 28, 2008

- Messages

- 27,026

Kz3r0

Arcane

- Joined

- May 28, 2008

- Messages

- 27,026

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 100,805

http://venturebeat.com/2014/02/19/w...-10-of-gamings-biggest-kickstarters/view-all/

Where are they now? An update on 10 of gaming’s biggest Kickstarters

Torment: Tides of Numenera

Developer: inXile Entertainment

Date Funded: April 5, 2013

Amount Funded: $4,188,927

What is it?: A role-playing game based on Monte Cook’s new tabletop RPG setting Numenera. Cook is best known for his work on tabletop games like Dungeons & Dragons, particular the 2nd editionAdvanced D&D setting Planescape

Update: Torment is still in heavy preproduction, inXile CEO Brian Fargo told GamesBeat. The team has generated about 800 pages of design documents and a prototype for one of the crisis areas. “We are working on some beautiful new screens, which we hope to show in the next 90 days or so,” he said. “We are thankful for the long design stage we were given thanks to crowdfunding.”

Original: inXile didn’t have any updates for us but said in its latest Kickstarter update that it’s been working on Torment’s aesthetics and environments. The studio has reached an agreement to license the same technology developer Obsidian is using to create Pillars of Eternity. This will give inXile a “stronger starting point for certain game systems and pipelines, including the creation of the 2D pre-rendered environments.”

“This means we will have more resources to invest on other aspects of the game, allowing us to achieve a higher quality overall,” said project lead Kevin Saunders.

Pillars of Eternity

Developer: Obsidian Entertainment

Date Funded: Oct. 16, 2012

Amount Funded: $3,986,929

What is it?: An isometric, party-based RPG in the same vein as Baldur’s Gate, Icewind Dale, and Planescape: Torment

Obsidian didn’t respond to our request for an update on Pillars of Eternity, but producer Rose Gomez Jr. said in a recent update that the game will be released sometime in Winter 2014. Gomez also added the following about stretch goals:

“After much discussion and consideration of the poll on our forums, we have decided not to pursue any additional stretch goals. Rest assured that the team is working hard on completing the game and including our current stretch goals.”

Wasteland 2

Developer: inXile Entertainment

Date Funded: April 17, 2012

Amount Funded: $2,933,252

What is it?: A sequel to the 1998 post-apocalyptic role-playing game Wasteland

Update: InXile just updated its beta/Early Access version of Wasteland 2 via Steam earlier this week, according to CEO Brian Fargo. This new version brings a host of changes, including a new inventory UI, destructible objects, improved combat animations, and new areas of the map to explore. Fargo said the response to the update has been positive. “The feedback on our changes has been strong and we are back in the top 10 for RPGs (top 20 overall) on Steam,” he said.

With Wasteland 2 slowly closing in on a release date, Fargo also commented on the time it’s spent in production. “Although sometimes people like to focus on us being late think it’s important to note that the initial Kickstarter date was an estimate, and once we raised 3x the money we increased the scope of the game at least 2x, which makes that initial estimate moot. The good news is that we are in the final stretch and it’s one of the most ambitious games I have ever worked on. I want to prove what a developer can do with crowdfunding.”