Posted

21 mins ago by

Eric Van Allen

A historical whodunnit

Real history is an interesting setting for games to use. Pulling in actual world events to tell a tale can be tricky, but

Pentiment does it in stride.

Pentiment is a passion project from

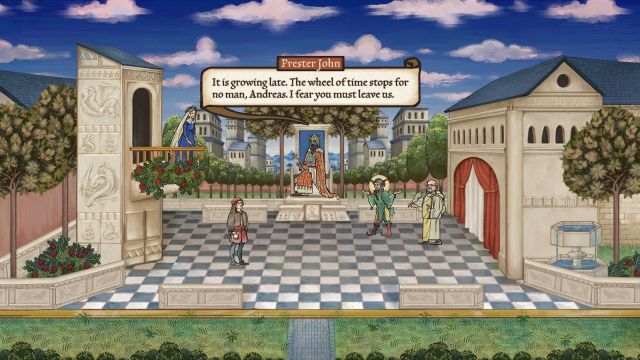

a small team of developers within Obsidian. It’s set in the tiny town of Tassing in Bavaria, in the late 15th and early 16th century. It’s a town with clear divides between the peasants and their fields, the townspeople’s crafted goods, and the double monastery looming just down the lane.

Every villager, sister, and monk in Tassing has a story. Each family has branches that grow out and interlock. It might seem too small a place to keep a secret. But as protagonist Andreas Maler soon discovers, those appearances are deceiving.

It’s a combination of history and detail, alongside a fantastic commitment to art direction, that give

Pentiment a true sense of place. It’s a role-playing adventure that fills its houses with details to discover, and difficult choices to make. Because someone has been murdered, and it’s on both Andreas, and you, to figure it out.

Pentiment (PC [reviewed], Xbox Series X|S)

Developer: Obsidian

Publisher: Microsoft

Released: November 15, 2022

MSRP: $19.99

When in Tassing

The story starts with Andreas waking up in the town of Tassing on a normal day. He’s a journeyman artist taking up residency in the local Kiersau Abbey. He works on commission for the brothers there, at the abbey’s scriptorium, while gradually putting together his masterpiece. Once it’s finished, he can head off to Nuremburg, where a workshop, wife, and future await.

Most of

Pentiment is played in a point-and-click adventure fashion. The player, as Andreas, can walk around town and interact with the locals. It’s dialogue-driven, though a few puzzles and minigames pop up here and there. None of them were particularly difficult, and mostly served a narrative purpose; whether it’s snapping sticks for kindling or solving a code, nothing seemed too dense or felt like a fail-state.

Rather, the drive is towards learning. Part of this is gaining info from characters. At first, it’s just getting to know your neighbor. And later, after some events have transpired and a body is discovered, it’s about learning what your neighbors might be hiding.

Comparisons to games like

Disco Elysium are easy to make. There isn’t as much role-playing here though, at least in a hard dice-rolling sense. At the beginning, you get to select some origin story information for Andreas. If you’re like mine, you can make your Maler a medical school dropout who liked getting into fistfights. Or you can have him be a learned theologian, or dip into the occult. Different areas he’s traveled to can influence what languages and customs are familiar to him.

These don’t really block off access in any way, but do offer options for extrapolation. Sometimes, that means an extra dialogue choice, and even in one case, an alternative puzzle solution. Most of the time, it added flavor to the experience. My Andreas had a history before arriving in Tassing, and it affected his stay in many small ways.

In Paradisum

An average slice of

Pentiment, once the discovery period has begun, will see Andreas running around the town and inquiring with locals. These usually eat up time, and that time is precious. Doing some favors for someone might get them to open up to you. But it might also put you in a disadvantageous position with others.

One early example puts Andreas between a rock and a hard place. He can help someone with their housework, but also assist in some mild blasphemy in the process. While this might endear him to them and get them to open up about why they intensely dislike another character, it might also put you out of favor with the local reverend and the abbey.

Pentiment is full of choices, big and small. And they’re rarely easy, too. I had to abandon any hope of a “golden route” fairly early, as that doesn’t seem like the goal here. Instead,

Pentiment centers much more on how you decide to spend your time, what you do with it, and how that affects the people around Andreas. Several decisions I made weighed on me until the credits rolled, and

Pentiment doesn’t pull punches in dealing with both the short and long-term consequences of your actions.

The world at your door

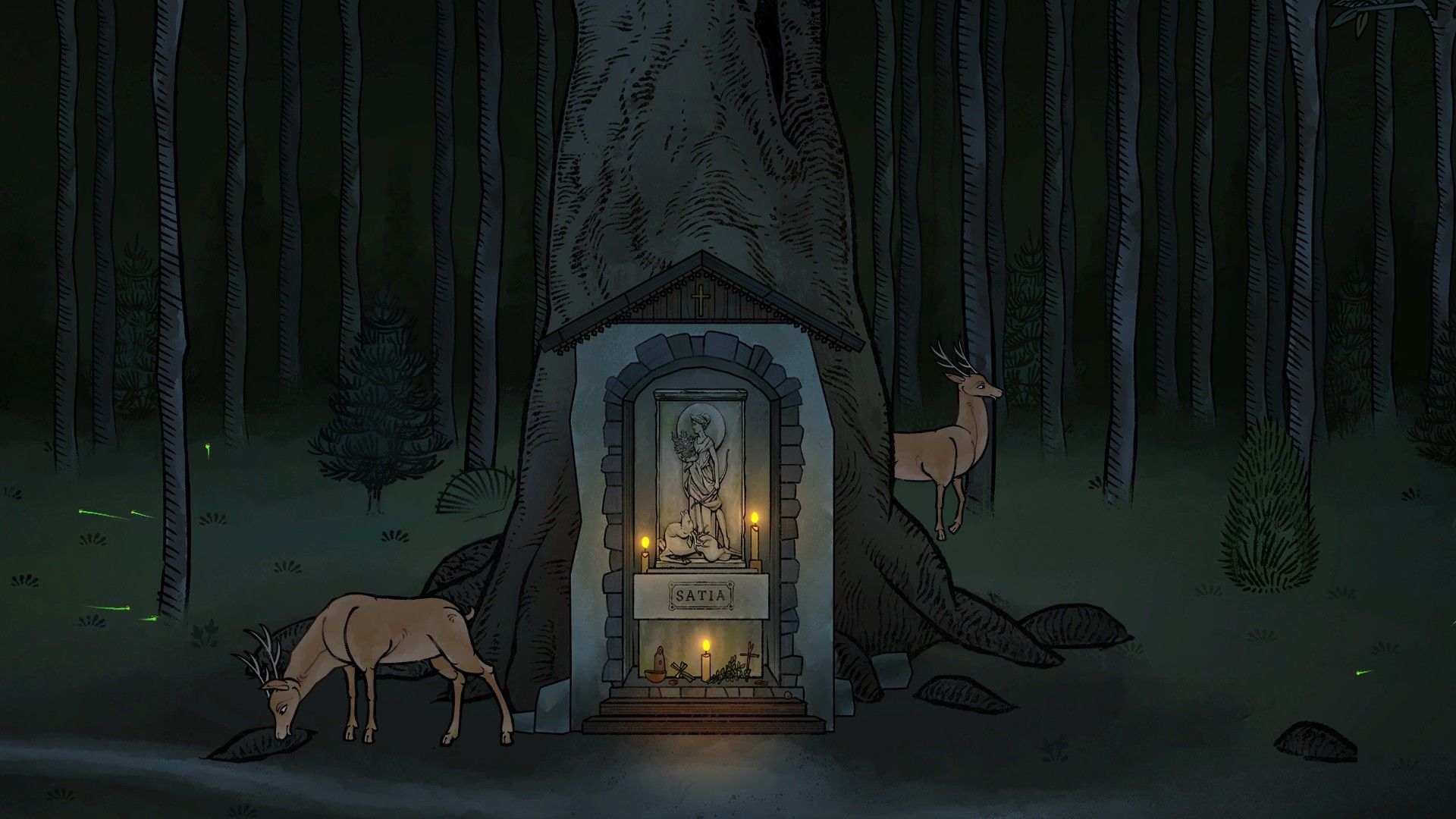

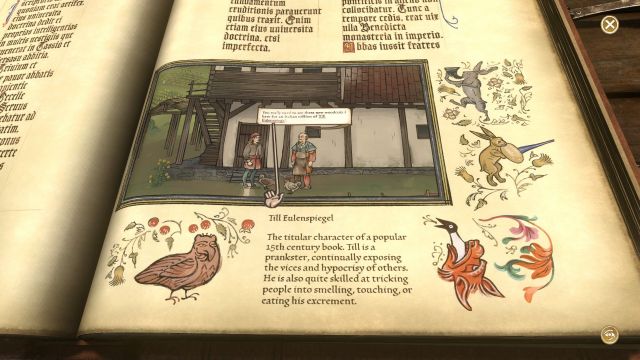

Being historical fiction,

Pentiment is also deeply steeped in its lore. It’s a major part of

Pentiment’s up-front appeal, and the team at Obsidian went into incredible detail making sure Tassing feels like it takes place in the right area and era.

The divides in wealth fester over time, as do long-held grudges between the church and those old enough to still cherish Pagan practices. Dialogues about an upstart named Martin Luther, different translations of classic texts, and the power dynamics of the town place

Pentiment squarely within its time period. An in-game glossary helps keep everything in context too, if you need a refresher.

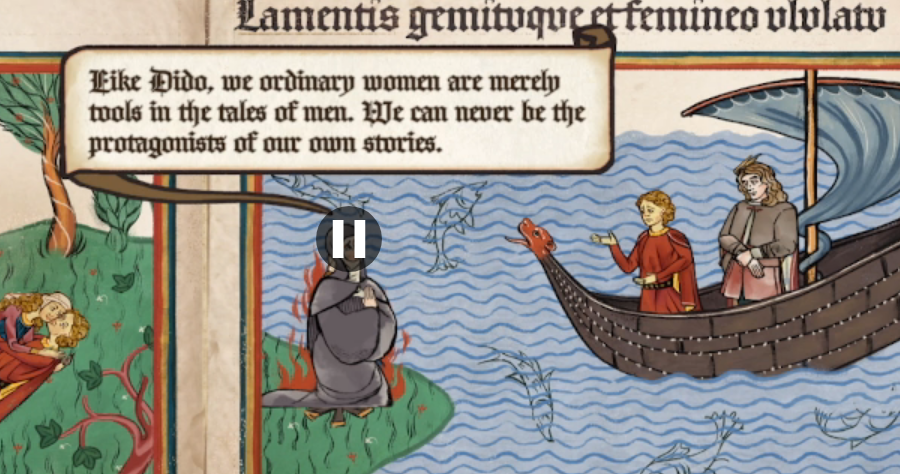

The art direction emphasizes this as well. All of

Pentiment is displayed in a gorgeous, classic illustrative style. But my favorite touch is the way conversations are displayed. Every character’s dialogue is shown as different types of communication, whether flourishing script or simple lettering, to even a stamp-and-press type-set for the local printer.

Everyone has their own assigned type, and they will even change as Andreas learns certain details about someone’s background or education. Typos will be made and fixed on the fly, letters stenciled and colored in, and holy phrases left for the end, as they require differently colored ink. It’s a wonderful detail that never got old through my roughly 20 hours with

Pentiment. Though if the fonts prove difficult to read, there’s a wealth of accessibility options to fine-tune them.

Long-buried secrets

All of this layers up an incredible historical foundation and sense of place, which

Pentiment then wields to tell an honest, emotional story. The murder mystery is an initial draw, but Andreas’ own issues, and the woes of the townsfolk, are also key components. Characters like Sisters Matilda and Illuminata, Brother Piero, Otto, Claus, and more are intensely memorable, with storylines that deeply resonated with me.

Without giving too much away, the story of

Pentiment shows how decisions and choices play out over a period of time. And how, over the years, both internal and external strife put pressure on those living in Tassing in different ways. No town lives in isolation, and

Pentiment shows how issues that seem far from your door are much closer than you’d think.

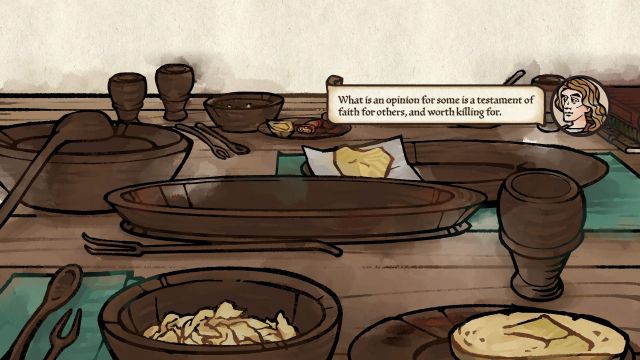

Because of this, the writing and story of

Pentiment are an absolute highlight, and some of my favorite beats of the year. The world and its inhabitants grow and suffer, and deal with so much over the course of time that you become endeared to them. There’s some really poignant discussions and writing on faith, belief, power, laws, and rights. My screenshots folder is littered with snippets that made me stop and pause for a moment, whether for a thoughtful reprieve or an emotional gut-punch.

Danse Macabre

Where

Pentiment sometimes struggles is getting exact info to the player, and communicating time investment for certain leads. Often, characters will let you know if a certain action is going to eat up a segment of your day. But looking into other leads, or diving into some side tasks, won’t eat up a segment of your day.

When the clock is ticking and Andreas is up against a deadline, this can lead to some indecision. Locating everything is another matter, too. While the in-game glossary holds maps, character info, and even leads, it doesn’t tell you where certain characters are. During some parts, I’d just find myself running circles around town, trying to find a specific person and determine whether talking to them was going to be a quick chat for some extra info, or cost me a chunk of my day.

Mouse and keyboard can feel finicky, especially when trying to click on a glossary term within a choice. It was sometimes a careful dance between looking into a term and making a choice, and I had to jump back out and in to undo some decisions I didn’t mean to make.

Pentiment also uses just an auto-save feature, meaning that if you’re not careful, you can lock yourself into certain choices. That’s nice to prevent save-scumming, which felt a bit antithetical to the story’s focus, but less so when you’re just trying to roll back an accidental selection. They’re small frustrations, but one’s I did run into more than a couple times.

Tangible history

As I think about my time with

Pentiment, I keep going back to one moment. One frequent gameplay section has you choose who Andreas shares a meal with for the day. These moments offer a chance to gain some insight into certain families. Understanding their dynamic can inform your investigation, or just sate a curiosity.

Through much of my early time, I ate with peasant families. As conversation proceeds, you make a selection of which food item to eat. In one case, the family puts more in front of you than themselves. It shows a bit of character, in that moment, as you’re given a tangible feeling of both their struggles and perseverance in spite of them. They maintain hospitality, even in the face of tightening taxes and pressure.

Then I ate with the abbot, who tried to tell me about his own hardships, in front of a lavish spread. And

Pentiment asked me how I felt about the church’s role in the current struggle. Boy, did I have opinions.

Pentiment is a compelling narrative adventure that pushes you to make decisions, and then see how those consequences play out. But it also has a dedication to showing how the people, as much as the town and ongoing intrigue, have to live with everything that goes down. It’s a murder mystery, but it’s also a decades-spanning story about people trying to make a life in a little town called Tassing. It’s gorgeous, crafted, and will certainly fit the bill for anyone seeking some historical intrigue with a complex but earnest heart inside.

9

Superb