Has the games industry turned tail on microtransactions?

Crate news?

Last week Monolith released an official statement announcing that as of 17th July, Shadow of War will no longer contain microtransactions. Buying Gold with real money will be gone for good on 8th May, and a couple of months later the market which erstwhile sold item chests, XP boosts and orcs for the Nemesis system will be dismantled completely. Apparently buying those orcs, rather than earning them in-game, "risked undermining the heart of our game," said Monolith, six months down the road from implementing that marketplace.

Six months ago the press was saturated with headlines about a new wave of intrusive microtransactions. Communities expressed their outrage, share prices dropped, oceans turned blood red. Now it's increasingly populated by news of their subsequent removal. If it wasn't for fear of having one's naivety etched indelibly onto internet record, the great microtransaction withdrawal movement of 2017/18 might be enough for one to proclaim that the practice was dead.

The reality of a multi-billion pound industry's business practices is, inevitably, nothing like that clear cut or easy to forecast. Still, the sheer number of controversies and about-turns from big publishers and major franchises in last six months demonstrate that what might have seemed like a good idea in the salad days of Q3 2017 is now a certain PR disaster. The times they are a-changin'.

The touch paper was really lit by Battlefront 2, and how EA and DICE handled the furore surrounding its pre-beta trials. Players invited to play the pre-release build, as you'll remember, were strongly critical of major characters (and their powerful abilities) being kept behind either a monetary paywall, or a 40-hour grind. In response, DICE tweaked made minor changes to item drop rates. It wasn't enough.

A miserly, RNG-based player reward system remained, and when one player discovered their $80 Deluxe Edition still required them to grind 40 hours to unlock Darth Vader they took to Reddit to voice their complaint. EA's reply on that thread became the most downvoted comment in the site's history. This time EA and DICE slashed price of character unlocks by 75% - but also lowered the credits earned from completing a campaign.

Amidst an oil fire of bad sentiment towards the game, the decision was finally made to pull microtransactions entirely on the day before release. They might return, said EA, at an unspecified later date, after some unspecified changes had been made. EA's stock value dropped 2.5% in 24 hours on launch day, and lost a total of $3 billion in stock value by the end of November.

In other words, a detailed blueprint on how not to handle a microtransaction backlash had been forged.

Imagine being a game developer during that period, knowing that the title you worked long hours on for years was about to go to market. And knowing it was full of microtransactions. Imagine how damp with sweat your phone-operating finger would be as you scrolled through the headlines about Battlefront 2. How could you avoid a similar fate? Something would have to give. And there's every indication that it did.

Back in the EA camp, Ghost Games acted swiftly when Need For Speed Payback's suspiciously slow progression system and paid loot boxes were met with hostility. Less than two weeks after launch, a statement went live announcing increased Rep and Bank rewards (XP and money to those of us with normal-sized car exhausts). Despite making this change a fortnight after Battlefront 2-gate, the developers insisted this economic rebalance was entirely unrelated.

In truth, EA felt the brunt of public disdain not simply because their microtransaction models were the most egregious, but because they were also the last of the big players to show their hand during the mad release scrum at the end of last year. They were the target of an accumulated anger that had been percolating for years, and was shown the red rag by September and October 2017's releases. Games with their own unpopular economies, and their own about-turns.

NBA 2K18 released to widespread criticism on 19th September 2017 for the latest changes it brought to an ever-more intrusive franchise microtransaction model. Virtual Currency multipliers for playing at higher difficulties were axed, while haircuts and tattoos for players' virtual ballers became one-use purchases rather than permanent ownership deals. Above all, there was a pervading sense that the entire game - a new quasi-MMO set on the shop-lined streets of a hyperconsumerist's fever dream - existed simply to coax players into buying VC with real money, and spending it on making their players able to hold a basketball without combusting with sheer ineptitude. 2K digital marketing director Ronnie '2K' Singh announced VC price cuts for haircuts, colours, and facial hair options on release day in response to 2K18's angry community reception.

Like EA's initial half-measure, it wasn't enough. The PS4 version of NBA 2K18 currently holds a critic score of 80 on Metacritic, and a user score of 1.6. Both are considerably lower than the previous game's critical numbers, but as Take-Two CEO Strauss Zelnick noted in a November earnings call, NBA 2K18 didn't seem to take a hit in sales or average daily users. Both increased on NBA 2K17s numbers, in fact.

What Zelnick told investors seems to reflect the wider industry's attitude to microtransactions: "There has been some pushback about monetization in the industry... People vote ultimately with the usage. And the usage on this title is up 30 percent in terms of average daily users."

That idea holds true of Assassin's Creed Origins, too. Launching in October 2017, it has since sold more than double what Syndicate managed two years prior. And it did so with a microtransaction model which neither sparked a major backlash nor was subject to rebalancing after release. Perhaps it was the specific implementation of Origins' paid content, which largely amounted to items you'd find in the world anyway, with the exception of a couple of item maps which had been available for free in previous entries in the series. Or perhaps it was the overall quality of the experience - it's hard to stay mad about those maps when you're atop the Great Pyramid, watching the sun play across the Iment Nome dunes.

There's a paradox in that, of course. If high sales numbers provide a license to pursue microtransaction models regardless of how they're received, low sales numbers also encourage microtransactions in order to make up the financial shortfall. Case in point: Despite Destiny 2's physical sales falling by 50% on its predecessor, and a vocal response from its community about the increased amount of RNG in player reward distribution and the fact that cosmetic shaders used to recolour items were now single use, it took until January 2018 for

Activision and Bungie to change anything.

Still, some were quicker to act when the forums lit up with impassioned capital letters, despite commercial underperformance. Forza Motorsport 7's initial sales figures lagged behind its predecessor despite its availability on PC for the first time, and people were not happy about its VIP Pass. Previously this single-purchase piece of DLC entitled you to a permanent 2x credits bonus across all events, but in Forza 2 it was limited to the first 25 races. Not that there was any mention of its finite usage in the store page listing, as

noted by one Redditor.

Two days after release, and after much spirited community feedback about the changes,

Turn 10 pulled a U-turn. The VIP Pass was restored to its permanent boost-giving powers, and owners were now gifted four cars, too.

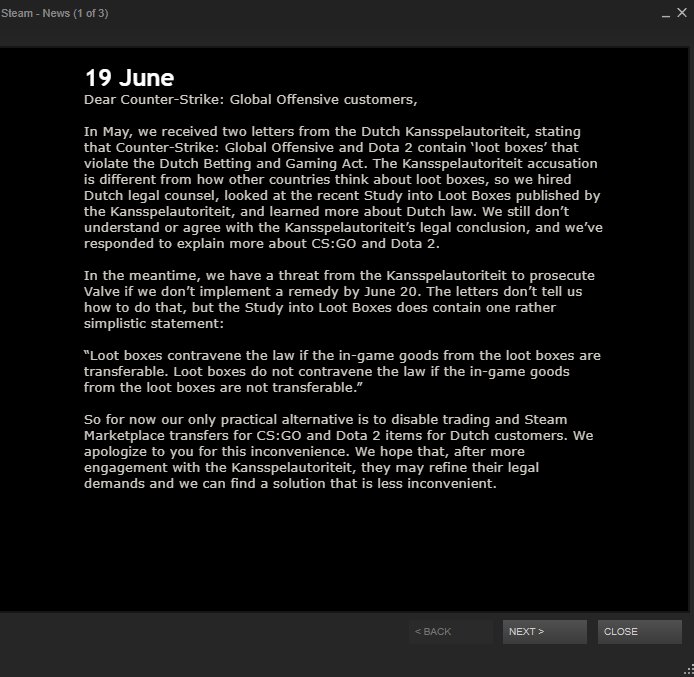

So long before it reached a head in Battlefront 2; before Belgian gambling authority bureaucrats worked to have EA's game banned, a narrative had already formed about hastily reneged microtransaction models and loot box systems. The solutions varied hugely in their severity. And it didn't always come from a fan backlash - there also seemed to be a desire on developers' part to move away from grinding and slot machine game design. Dawn of War 3's developers gutted the Skulls currency (obtained via in-game actions only) from their game several months after its release in April 2017, freeing players to experiment with Elite units and Doctrines without the grind. That followed Overkill buying back the franchise rights to Payday from 505 Games in 2016, and immediately removing the microtransactions they'd previously promised never to include. The implied narrative there was clear: the developers never wanted this, and now they've fixed it.

There are precedents even before that: in 2014, when Shia Labeouf popped a paper bag on his head for art and Kim Kardashian broke the internet, Digital Extremes were busy removing a specific $0.67 microtransaction that allowed players to recolour virtual pets called Kubrows. Upon discovering that one player had bought it 200 times hoping for a very specific set of buffs, the devs canned it. "It's just like, 'oh my dear god, what have we done?"

he told Noclip. "We've created a slot machine."

It's worth noting that although this happened back in 2014, it didn't make the headlines until March 2018. Aka: the great microtransaction withdrawal movement of 2017/18

And that makes a lot of sense, because public interest in this topic has never been higher. We've entered an era in which publishers and developers are actually using the absence of microtransactions from their upcoming games as a PR strategy, as evidenced by Irony Galaxy's latest game, Extinction. "Extinction does not include microtransactions" reads a black and white disclaimer message at the beginning of its trailers, calling to mind the legal disclaimers that began each episode of Jackass.

Well, you can't be clearer than that about it.

Far from simply being a bit coy about their loot boxes, developers are now actively using an anti-microtransaction stance as an easy PR win. Increasingly, we see developers take apparent delight in confirming their absence. "No freakin way!" God of War game director Cory Barlog told a fan on Twitter who asked if there'd be microtransactions in his upcoming game.

"Hell no" said Marvel's Spider-Man creative director Brian Intihar

when asked the same question by Game Informer, as if he were reading from the same playbook.

From our vantage point a quarter-way through 2018, the outlook appears rosy. Games are dropping their microtransaction models all over the place, while others are chest-beating about resisting their economic allure. But the real barometer for change will be the releases of Q3/Q4 2018. The annualised series and big-hitter publishers that barely got away with their monetisation models the last time around, and had to make revisions to satisfy their players. In the present climate, it feels as though a publisher mat as well announce that it's upcoming game is responsible for world hunger as admit that it contains the dreaded M-word.

But in an industry where product prices have remained largely the same for decades while product costs have escalated wildly, margins still need to be made. Videogames must remain fundamentally profitable ventures for their creators, and if those creators move away from the devil we know in order to make those profits, where might they look next for solutions? Maybe the answer is simply 'good quality products whose value and appeal are intrinsic' - but does that ring true of the industry that tried monetising hats and crates in the first place?