-

Welcome to rpgcodex.net, a site dedicated to discussing computer based role-playing games in a free and open fashion. We're less strict than other forums, but please refer to the rules.

"This message is awaiting moderator approval": All new users must pass through our moderation queue before they will be able to post normally. Until your account has "passed" your posts will only be visible to yourself (and moderators) until they are approved. Give us a week to get around to approving / deleting / ignoring your mundane opinion on crap before hassling us about it. Once you have passed the moderation period (think of it as a test), you will be able to post normally, just like all the other retards.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Random Adventure Game News Thread

- Thread starter Jaesun

- Start date

Nice. I actually like the games, they are pretty fun 2-3 hours when you want something more relaxing

Edit since I am here, this previously available on itch free adventure game was added to steam for those of you who like to have everything in one place:

Tad indulgent with inventory items, not a fan tbf

Released. Not sure if it's in English or Spanish only.They started working on the conversion of Laura Bow 1: https://github.com/Pakolmo/LB1PnCNice, I hated suffering through it via text parser in a playthrough a few years back so this will be handy for future replays.This wasn't posted here but Police Quest 2 got a conversion to point and click:

English patch here: https://github.com/Pakolmo/PQ2PnC

https://pakolmo.netlify.app/laurabow1_thecolonelsbequest_point_and_click

https://www.abandonsocios.org/index.php?topic=19654.0

Modron

Arcane

- Joined

- May 5, 2012

- Messages

- 11,162

Free christmas time gift from the guy behind: https://store.steampowered.com/app/1407420/Milo_and_the_Magpies/

Something near and dear to codexers:

Something near and dear to codexers:

Ah yes. Complaining about pirates by doing copyright infringement.

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 100,078

Broken Sword 2: https://www.filfre.net/2024/01/televising-the-revolution/The Digital Antiquarian on Broken Sword: https://www.filfre.net/2022/07/broken-sword-the-shadow-of-the-templars/

For all of its high production values, the game was widely perceived by the gaming press as a second-string entry in a crowded field plagued by flagging enthusiasm. Computer Gaming World‘s review in the United States reads as a more reserved endorsement than the final rating of four stars out of five might imply. “The lengthy conversations often drag on before getting to the point,” wrote the author. If you had told her that Broken Sword — or rather Circle of Blood, as she knew it — would still be seeing sequels published in the second decade after such adventure standard bearers as King’s Quest and Gabriel Knight had been consigned to the videogame history books, she would surely have been shocked to say the least.

Ah, yes, Gabriel Knight… the review refers several times to that other series of adventure games masterminded by Sierra’s Jane Jensen. Even today, Gabriel Knight still seems to be the elephant in the room whenever anyone talks about Broken Sword. And on the surface, there really are a lot of similarities between the two. Both present plots that are, for all their absurdity, extrapolations on real history; both are very interested in inculcating a sense of place in their players; both feature a male protagonist and a female sidekick who develop feelings for one another despite their constant bickering, and whose rapport their audience developed feelings for to such an extent that they encouraged the developers to make the sidekick into a full-fledged co-star. According to one line of argument in adventure-game fandom, Broken Sword is a thinly disguised knock-off of Gabriel Knight. (The first game of Serra’s series was released back in 1993, giving Revolution plenty of time to digest it and copy it.) Many will tell you that the imitation is self-evidently shallower and sillier than its richer inspiration.

But it seems to me that this argument is unfair, or at least incomplete. To begin with, the whole comparison feels more apt if you’ve only read about the games in question than if you’ve actually played them. Leaving aside the fraught and ultimately irrelevant question of influence — for the record, Charles Cecil and others from Revolution do not cite Gabriel Knight as a significant influence — there is a difference in craft that needs to be acknowledged. The Gabriel Knight games are fascinating to me not so much for what they achieve as for what they attempt. They positively scream out for critical clichés about reaches exceeding grasps; they’re desperate to elevate the art of interactive storytelling to some sort of adult respectability, but they never quite figure out how to do that while also being playable, soluble adventure games.

Broken Sword aims lower, yes, but hits its mark perfectly. From beginning to end, it oozes attention to the details of good game design. “We had to be very careful, and so we went through lots of [puzzles], seeing which ones would be fun,” says Charles Cecil. “These drive the story on, providing rewards as the player goes along, so we had to get them right.” One seldom hears similar anecdotes from the people who worked on Sierra’s games.

This, then, is the one aspect of Broken Sword I haven’t yet discussed: it’s a superb example of classic adventure design. Its puzzles are tricky at times, but never unclued, never random, evincing a respect for its player that was too often lost amidst the high concepts of games like Gabriel Knight.

Of course, if you dislike traditional adventure games on principle, Broken Sword will not change your mind. As an almost defiantly traditionalist creation, it resolves none of the fundamental issues with the genre that infuriate so many. The puzzles it sets in front of you seldom have much to do with the mystery you’re supposed to be unraveling. In the midst of attempting to foil a conspiracy of world domination, you’ll expend most of your brainpower on such pressing tasks as luring an ornery goat out of an Irish farmer’s field and scouring a Syrian village for a kebob seller’s lucky toilet brush. (Don’t ask!) Needless to say, most of the solutions George comes up with are, although typical of an adventure game, ridiculous, illegal, and/or immoral in any other than context. The only way to play them is for laughs.

And this, I think, is what Broken Sword understands about the genre that Gabriel Knight does not. The latter’s puzzles are equally ridiculous (and too often less soluble), but the game tries to play it straight, creating cognitive dissonances all over the place. Broken Sword, on the other hand, isn’t afraid to lean into the limitations of its chosen genre and turn them into opportunities — opportunities, that is, to just be funny. Having made that concession, if concession it be, it finds that it can still keep its overarching plot from degenerating into complete absurdity. It’s a pragmatic compromise that works.

I like to think that the wisdom of its approach has been more appreciated in recent years, as even the more hardcore among us have become somewhat less insistent on adventure games as deathless interactive art and more willing to just enjoy them for what they are. Broken Sword may have been old-school even when it was a brand-new game, but it’s no musty artifact today. It remains as charming, colorful, and entertaining as ever, an example of a game whose reach is precisely calibrated to its grasp.

In the end, then, Broken Sword II suffers only by comparison with Broken Sword I, which does everything it does well just that little bit better. The backgrounds and animation here, while still among the best that the 1990s adventure scene ever produced, aren’t quite as lush as what we saw last time. The series’s Art Deco and Tintin-inspired aesthetic sensibility, seen in no other adventure games of the time outside of the equally sumptuous Last Express, loses some focus when we get to Central America and the Caribbean. Here the game takes on an oddly LucasArts-like quality, what with the steel-drum background music and all the sandy beaches and dark jungles and even a monkey or two flitting around. Everywhere you look, the seams show just a little more than they did last time; the original voice of Nico, for example, has been replaced by that of another actress, making the opening moments of the second game a jarring experience for those who played the first. (Poor Nico would continue to get a new voice with each subsequent game in the series. “I’ve never had a bad Nico, but I’ve never had one I’ve been happy with,” says Cecil.)

But, again, we’re holding Broken Sword II up against some very stiff competition indeed; the first game is a beautifully polished production by any standard, one of the crown jewels of 1990s adventuring. If the sequel doesn’t reach those same heady heights, it’s never less than witty and enjoyable. Suffice to say that Broken Sword II is a game well worth playing today if you haven’t done so already.

It did not, however, sell even as well as its predecessor when it shipped for computers in November of 1997, serving more to justify than disprove Virgin’s reservations about making it in the first place. In the United States, it was released without its Roman numeral as simply Broken Sword: The Smoking Mirror, since that country had never seen a Broken Sword I. Thus even those Americans who had bought and enjoyed Circle of Blood had no ready way of knowing that this game was a sequel to that one. (The names were ironic not least in that the American game called Circle of Blood really did contain a broken sword, while the American game called Broken Sword did not.)

That said, in Europe too, where the game had no such excuses to rely upon, the sales numbers it put up were less satisfactory than before. A PlayStation version was released there in early 1998, but this too sold somewhat less than the first game, whose relative success in the face of its technical infelicities had perchance owed much to the novelty of its genre on the console. It was not so novel anymore: a number of other studios were also now experimenting with computer-style adventure games on the PlayStation, to mixed commercial results.

With Virgin having no interest in a Broken Sword III or much of anything else from Revolution, Charles Cecil negotiated his way out of the multi-game contract the two companies had signed. “The good and the great decided adventures [had] had their day,” he says. Broken Sword went on the shelf, permanently as far as anyone knew, leaving George and Nico in a lovelorn limbo while Revolution retooled and refocused. Their next game would still be an adventure at heart, but it would sport a new interface alongside action elements that were intended to make it a better fit on a console. For better or for worse, it seemed that the studio’s hopes for the future must lie more with the PlayStation than with computers.

Revolution Software was not alone in this; similar calculations were being made all over the industry. Thanks to the fresh technology and fresh ideas of the PlayStation, said industry was entering a new period of synergy and cross-pollination, one destined to change the natures of computer and console games equally. Which means that, for all that this site has always been intended to be a history of computer rather than console gaming, the PlayStation will remain an inescapable presence even here, lurking constantly in the background as both a promise and a threat.

Falksi

Arcane

I've been trying a lot of P&CA games the past few months and having little luck with them, most are either badly designed or woke AF. The Wadjet Eye games do a lot of stuff well, but usually drop the ball and the newer the game the more woke it is.

But I returned to games like the early Monkey Island series and I Have No Mouth And I Must Scream and thoroughly enjoyed them, so I 've certainly not gone off the genre.

So are there any recommendations from you all of more modern P&CA games actually worth getting? I'd be interested to get your top 3-5?

But I returned to games like the early Monkey Island series and I Have No Mouth And I Must Scream and thoroughly enjoyed them, so I 've certainly not gone off the genre.

So are there any recommendations from you all of more modern P&CA games actually worth getting? I'd be interested to get your top 3-5?

Morpheus Kitami

Liturgist

- Joined

- May 14, 2020

- Messages

- 2,713

The Rusty Lake/Cube Escape games are pretty interesting. All the games by the company are basically a connected series involving a weird mystery that starts with someone getting murdered and goes in a weird horror story direction. The first games in the series are free, and as time went on they made commercial ones. They're a bit on the easy side, but a few were challenging.I've been trying a lot of P&CA games the past few months and having little luck with them, most are either badly designed or woke AF. The Wadjet Eye games do a lot of stuff well, but usually drop the ball and the newer the game the more woke it is.

But I returned to games like the early Monkey Island series and I Have No Mouth And I Must Scream and thoroughly enjoyed them, so I 've certainly not gone off the genre.

So are there any recommendations from you all of more modern P&CA games actually worth getting? I'd be interested to get your top 3-5?

KeighnMcDeath

RPG Codex Boomer

- Joined

- Nov 23, 2016

- Messages

- 15,848

I like the Rusty Lake games but I have no mouth & I must scream is classic gold.

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 100,078

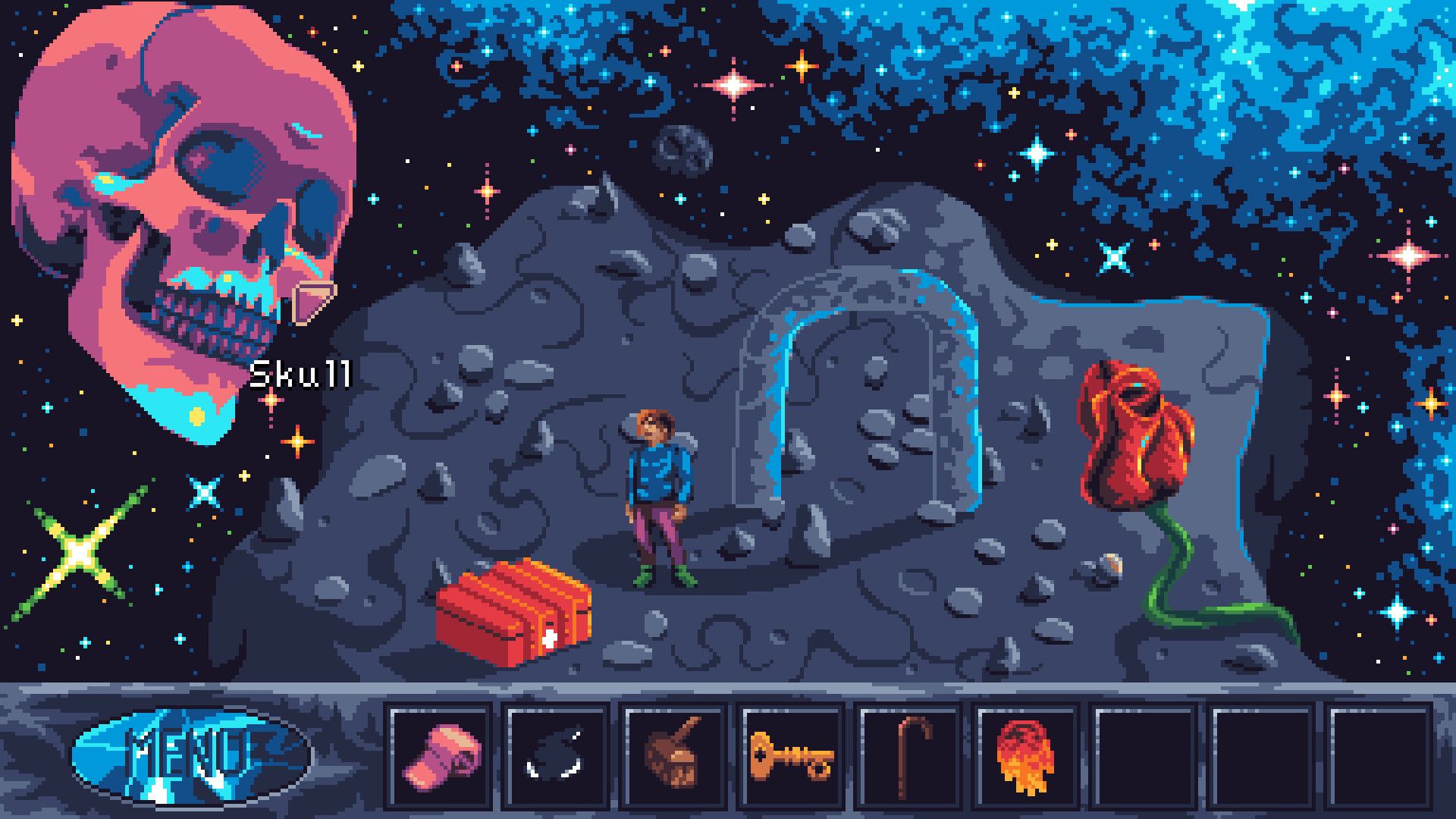

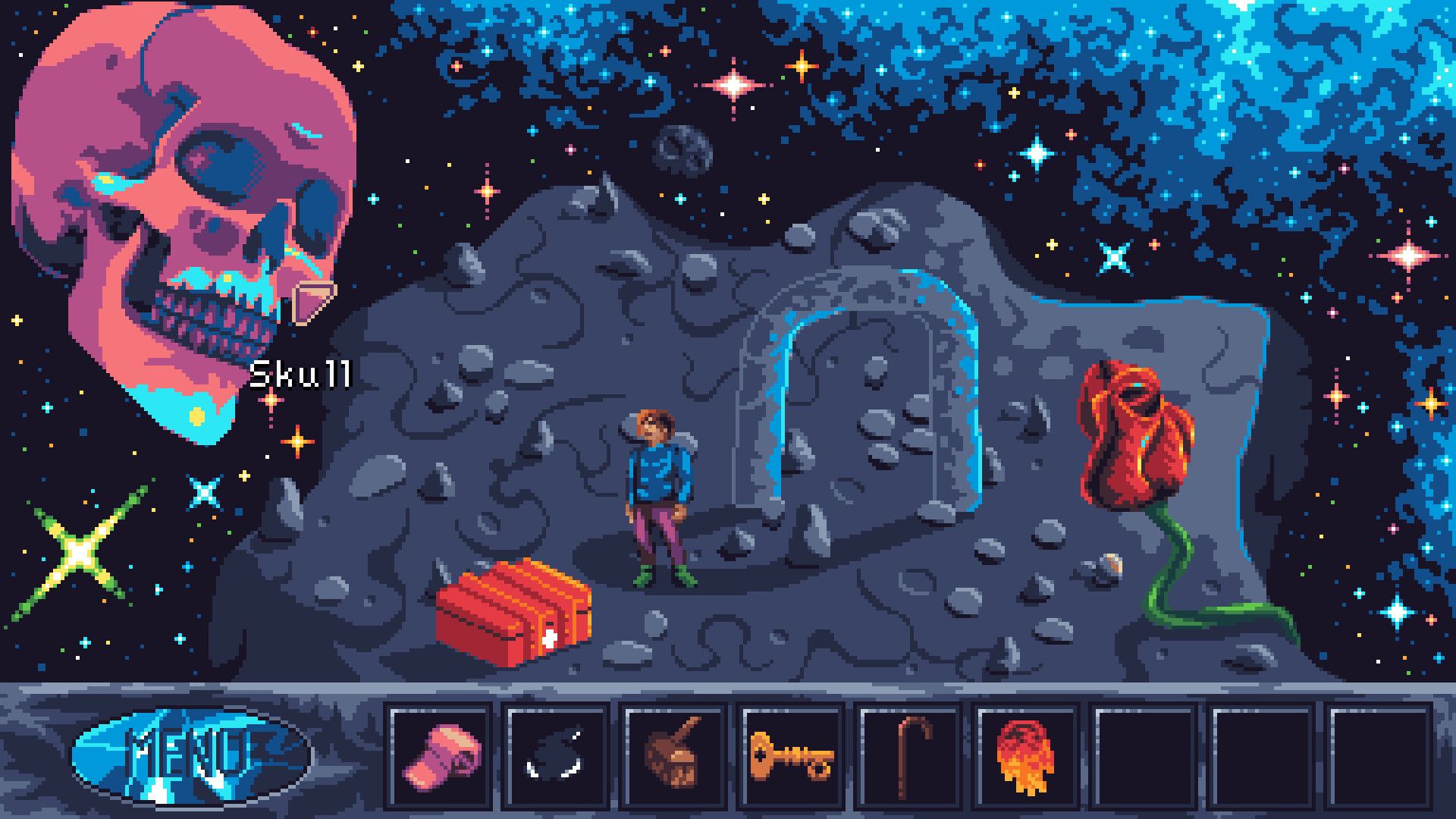

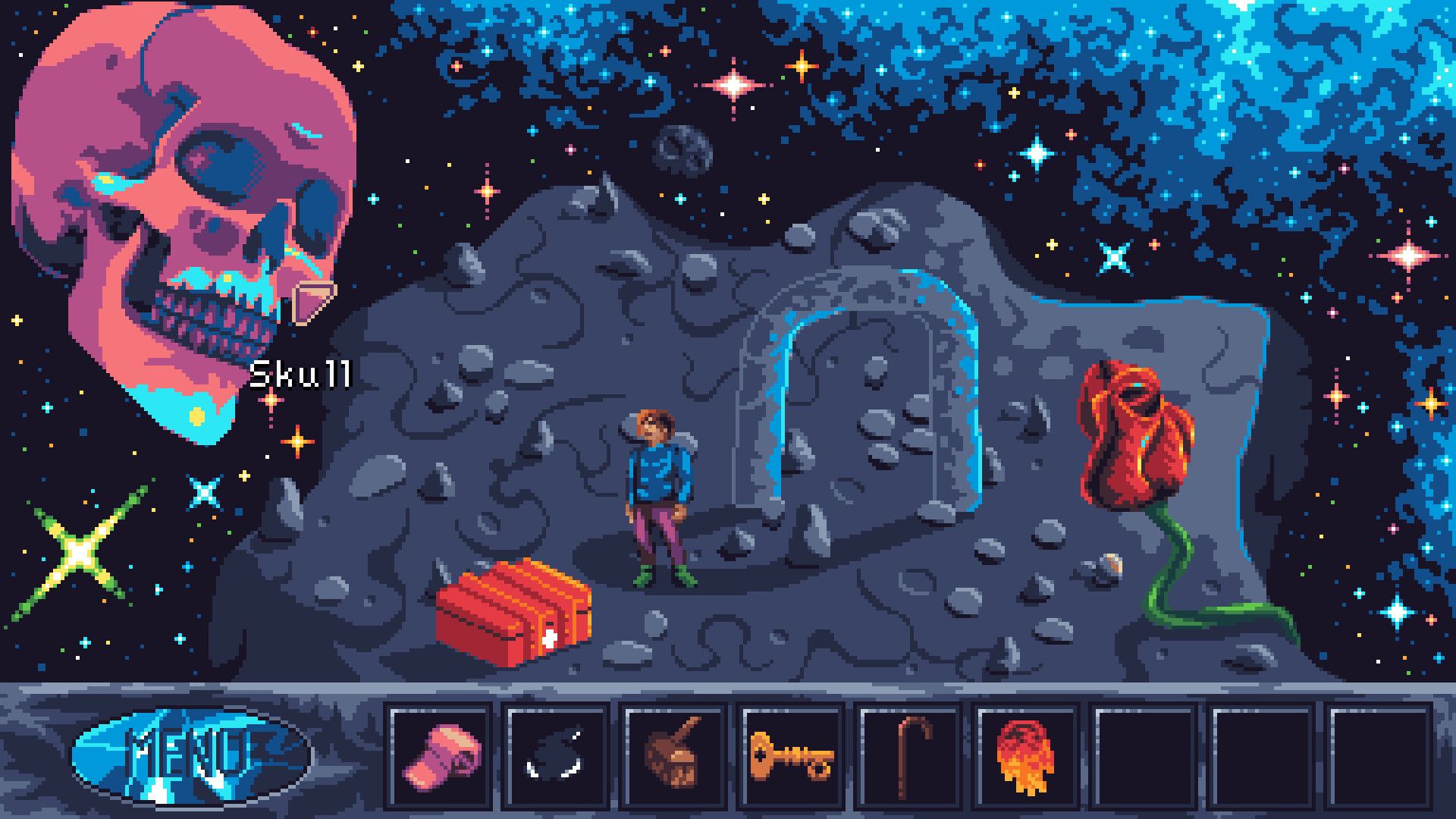

Finally a sequel to Kyrandia 2!

It's short, but the constant backtracking and random item appearances make it feel longer in a bad way. Feels like it was supposed to have been about three times the length at some point but got cut back. It's still fun though.

It's short, but the constant backtracking and random item appearances make it feel longer in a bad way. Feels like it was supposed to have been about three times the length at some point but got cut back. It's still fun though.

Even the very end is just HoF divided by three. Thwack the evil magician once instead of three times in a room with 1 instead of 3 big green consoles. In space.

Last edited:

too much wacky shit

KeighnMcDeath

RPG Codex Boomer

- Joined

- Nov 23, 2016

- Messages

- 15,848

Zanthia needed a good screwing. That Kyrandia 2 though, it was ok but 1 was better.

Wacky indeed…

Wacky indeed…

3 others

Augur

- Joined

- Aug 11, 2015

- Messages

- 279

There's a demo out for Death of the Reprobate in Steam, which is the successor to the wonderful Procession to Calvary:

Looks really good, I love slightly surreal wacky stuff.Zanthia needed a good screwing. That Kyrandia 2 though, it was ok but 1 was better.

Wacky indeed…

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 100,078

https://www.timeextension.com/featu...ide-story-of-terry-pratchetts-discworld-games

INTERVIEW "John Cleese Told Us To F**k Off" - The Inside Story Of Terry Pratchett's Discworld Games

"Terry's way of looking at the world was ‘Ordinary people in an extraordinary world’"

In the mid-to-late '90s, the UK developer Perfect Entertainment partnered with the author Terry Pratchett to produce three games based on the writer's Discworld series of novels.

The series, which began all the way back in 1983, with the publication of The Colour of Magic, has won countless awards, shifted over a hundred million copies, and gone on to comprise an impressive 41 books in total (not counting its various spin-offs, graphic novels, and companions). Its final novel The Shepherd's Crown was published in August 2015 — five months after the author's unfortunate passing at the age of 66 from complications related to Alzheimer's.

As the name suggests, all of the books (and the games by extension) take place in an unconventional location called The Discworld — which is commonly described as a disc-shaped planet balanced on the backs of four elephants standing atop a giant turtle floating through space. Its various stories typically focus on the adventures (or misadventures) of The Disc's inhabitants, with some of the most memorable characters featured in its page including the wizard Rincewind, the witches Granny Weatherwax and Nanny Ogg, and the Ankh Morpork City Watch (to name just a few).

Even to this day, we constantly find ourselves returning to these books regularly and have always been fascinated with the video game adaptations of the series. So recently we decided to track down Gregg Barnett, the designer of the Discworld video games, to find out more about how they came to be, what it was like collaborating with Terry Pratchett, and if there's any possibility of any potential reissues or remasters of in the future. You can read a transcript of our conversation below (edited for length and clarity):

Time Extension: To start, it would be great to hear, what was your familiarity with the Discworld books like before you ended up pursuing the license? How did you first become aware of the books?

Barnett: People had spoken about them. So when I read the first couple, to me, I saw the foundation of a world and instances that would make good conversations in a game or good little events or puzzles. So before I even designed the game, I had read all the books that had been published up to that point – there might have been 9 or 10. I think we were up to Moving Pictures at that point or the second Witches book Sourcery. At that point, it was the biggest thing in the science-fiction fantasy world. This was pre-Harry Potter.

The first Discworld borrows its plot from the novel Guards! Guards!, but replaces Vimes with the hapless wizard Rincewind — Images: Psygnosis

Time Extension: What were those initial negotiations like with Terry Pratchett? In the past, I believe there had been a Colour of Magic text adventure and that hadn’t done that well. And then, there was Simon the Sorcerer, where I believe Adventure Soft had tried to get the license and couldn’t. So I’m wondering, where was Terry’s head at concerning video game adaptations of his work?

Barnett: It’s a long story, I suppose. So I was in Melbourne and wanted to start Perfect Entertainment and I decided that Discworld would be the perfect vehicle for an adventure game. So I designed the game or the first version of the game. The first version was a bit different from the one that we ended up making, in that it had some RPG elements in there to a small extent and some other things — I can’t remember what they all were. But anyway, it was quite a complex design and once I’d done that, I sent it over to Angela (my business partner) in England and she approached Colin Smythe who was Terry Pratchett’s agent in London.

Terry said, ‘Let’s talk to them’ based on the fact there was a design and it wasn’t somebody coming in cold. I think by that point, I’d also gotten to the second design, which was exactly puzzle for puzzle what the end game ended up with. So Terry said to me to meet him in a theatre in Stratford-Upon-Avon, which was the theatre, I believe, where Stephen Briggs put the Discworld plays on. He took us to meet what he called some of the Discworld family. And basically, he read the design, liked it, and said, ‘Yeah.’

He didn’t even really haggle money or anything. He wasn’t too concerned about that. I was under the assumption at that time that we were the first people who had ever spoken to him because it was extremely easy — apart from the fact I had to do three weeks doing a detailed design. He was extremely friendly and the only debate and argument we had wasn’t with him, it was with the agent. The agent kept suggesting, ‘Why can’t you just do The Colour of Magic?’ And I said, ‘No, I want the Discworld. The whole Discworld.'

The map of the city of Ankh-Morpork, taken from Discworld 1 — Image: Psygnosis

Afterward, so many people asked us, like publishers from EA to Psygnosis, ‘How did you get the deal? We went out to the agent with the big cheque in hand and we’ve just been told to piss off basically.’ I said, ‘I didn’t even have a cheque in hand. We didn’t even really talk about money. I just handed over a design.’

Time Extension: You mention that several publishers were amazed that you’d managed to obtain the license. How easy then was it to find a publisher for the game?

Barnett: I mean, in the case of Discworld 1, we actually started by speaking to Sierra On-Line in America. And we signed the contract with Sierra. I went over to the headquarters in California and spoke to Ken and Roberta Williams and we started working on the game on their engine.

At the time I was over there, they had this big New England barn with hundreds of employees and then all of a sudden it sort of tanked and they were leaking money everywhere so they cancelled all external projects. So the game got cancelled by them and it came back to us obviously. So we had some art and some scripting and everything but because we had been using their engine, we didn’t even have an engine at that point. So we decided we’d create our own engine and that’s when we started our Manchester team to build it.

We actually advertised in the English Computer Games Trade Magazine CTW that we wanted a publisher for the Discworld game. And we got three calls, I think, on the first day: Electronic Arts, Psygnosis, and I can’t remember who the third was.

Josh Kirby's amazing cover for Guards! Guards! — Image: Josh Kirby / Gollancz

Electronic Arts came in first and they said they were interested but they would get back to us. Then Psygnosis came down from Liverpool that same week and their approach was the total opposite to EA. Whereas EA said, ‘Yes, we like it, but we’re going to go away and think about it', Psygnosis said, ‘We’re not leaving the office until you tell us yes or no.’ So they were basically sitting in our office and we were trying to figure out, ‘Do we go with these guys?' I don’t think by then they had let it be known that they’d tried to get Discworld themselves, but it came out soon after that they had tried very hard to get it. So we agreed to sign up with them and they handed over the advance.

Time Extension: The first game obviously draws somewhat on the plot of Guards! Guards! with the appearance of the dragon. What about that premise specifically appealed to you? Was that just one of your favourites from the books you'd read or did you just think that was an interesting concept to hang the game on?

Barnett: It was an interesting concept. I had actually said when I spoke with Terry that it was the first book that popped out when I was reading where it was like, ‘Wow, this is a full screenplay sort of plot here. This has got backstories and loops around. It isn’t just a sequential thing with good gags.’ So there was a deep story and I could see how it could be layered into a game.

Obviously, what you are looking for in a point-and-click adventure puzzle game, or at least what I was looking for, was something that could be broken up into 3-4 acts and then you could expand it out and have multiple quests related to an overarching thing. That sort of structure of the secret society and the dragon behind it all — all of that was ideal for me. Then it was easy to do gags and hang them off of that — whether they were slapstick ones or stupid ones or Terry Pratchett ones or Monty Python ones or whatever.

Besides Terry's work, we also had the advantage of the supporting books from Stephen Briggs, such as The Discworld Companion. So we had a guide to the world as well. It’s very easy to look at Discworld and say it was an ad-hoc mish-mash of lots of things (which it was), but at least in Terry's point of view there was consistency underneath it all and we had to understand that so we didn’t break any rules as he or his fan saw them. So the companion was ideal for that sort of thing.

Subscribe to Time Extension on

Time Extension: The CD-ROM version of the first games includes Eric Idle in the role of Rincewind. Did Terry have any suggestions in terms of the voice casting?

Barnett: He did after the event – after I had already cast it. I don’t think I actually asked him who should voice Rincewind. The initial person we spoke to was John Cleese and he actually told us to ‘Fuck off’. That’s what he said: ‘Fuck off, I don’t do games.’ So we spoke to Eric Idle and the rest is history. During the recording session, I mentioned to Eric what John said, and he said, ‘Yep, that sounds like John.’ But after that, Terry did say that his idea of Rincewind was always based on Rodders out of Only Fools & Horses.

Beyond that, his only comment was obviously the librarian is an orangutan and not a monkey, but that was more of a joke that he made as a comment in an email. You’ve got to bear in mind that his main interest was in making the game loyal to the fans and what they believed Discworld was. He started things off, but quite often because of misunderstandings and fan beliefs, things changed and they weren’t how they started.

Time Extension: Do you have any insight into how you approached the world and its characters in while designing the first game?

Barnett: Terry's way of looking at the world was ‘Ordinary people in an extraordinary world’. His characters weren’t extraordinary. Even ones like the Cohen character who tried to be a hero was an old guy hobbling around. There weren’t any exceptional heroes — Rincewind was as flawed as you could get a hero to be — but the world and the opportunities for misunderstandings and stuff were huge in the way he portrayed it.

A routine visit to the retrophrenologist — Image: Psygnosis

The key characters were obviously the Terry Pratchett characters of Rincewind, the wizards, Death, and the witches – all those characters that were staples in the book – and a lot of effort was put in to make sure they were as close as in those days we could get them to how not just Terry but the fans understood them to be. And then we sprinkled in original characters that could have been in the books, to hang more extravagant stuff off if need be. And Terry would actually add to those, like in Discworld 1, I had the psychologist or something and Terry turned him into a retrophrenologist (where they hit people with a hammer to change their personality). So he would play along with the new characters.

Time Extension: One of the big things about the original game that kind of got criticized at the time of release was the puzzles. What are your thoughts on this?

Barnett: Obviously, some people have said Discworld 1 in particular is super hard, but the interesting thing is the way I designed it was if you just went step by step through any particular puzzle strand or any particular quest and just followed it step by step, it would lead you a little bit by the nose.

But because there was, at any given time, three or four or more strands open and the inventory did get quite large at times, experienced players who were taking shortcuts got tangled up more often than not.

And it was interesting because we even got mail from people in their 80s saying how easy they found it and that it was such a good experience. They just played it through the way the story led them by the nose. But then you had experts who had done King’s Quest and Simon the Sorcerer and so on saying, ‘Oh we can’t do this. These puzzles are so crazy.’ It was just interesting. So in Discworld 2, I made it so there were multiple ways of getting to the same answer.

Time Extension: In Discworld II, you also got an original song from Eric Idle. I’m wondering, how did that come about?

Barnett: Discworld II had a bigger budget. There was already some success and there was a clamouring for a sequel – and I already had an idea for what the sequel was going to be anyway; that was more to do with books based on the death line and the Moving Pictures ones. So films and death.

So because I had a scene with Eric on the cross as Bone Idle — which I remember getting to that part and Eric saying, ‘You’re causing me childhood trauma. They used to call me bone idle at school’ — I actually asked him whether he could just do another version of Bright Side of Life, but make it Look on the Bright Side of Death because I was obviously trying to play around with those words.

Discworld II saw Eric Idle voice a bunch of characters, including Bone Idle — a not-so-subtle allusion to Monty Python's Life of Brian — Image: Psygnosis

He said, ‘Yeah, maybe’ and he went away and he came back to me and said, ‘Look, I don't want to collaborate. I'll do something for free. I’m in Las Vegas and I’ve got some mates who are the best jazz musicians in the world. We’ve all agreed we’re going to spend a few days and just have a great time and do something and I’ll give it to you at the end. If you’re happy, you can use it. We’re not going to charge you anything for it..’ And he came back and it was good, and so we then took it and we animated it where we had the band and death and everything, and the skeleton singers and skeleton chorus girls and whatever.

Subscribe to Time Extension on

Subscribe to Time Extension on

Time Extension: When it came to Discworld Noir and this idea of doing a noir take on the Discworld universe, what was the inspiration for that? In the past, I interviewed Chris Bateman, who was your co-designer on that project. He told me that it initially started with you and Terry having a chat somewhere over dinner. Is that your memory of events?

Barnett: Sort of, but not quite. Basically, I said to Terry, ‘We need to do a third game.’ Now I wanted to do a third game and I knew what I wanted to do, but I was a bit wary about the next part. Then Terry said, ‘Haven’t people seen everything? It would have to be something totally original.’ And that’s when I suggested doing a detective one or doing a noir version of the Discworld because there hadn’t been any detective novels.

Lewton could switch between being a werewolf and a human to investigate new leads based on scents — Image: GT Interactive

He had the City Watch but he hadn’t had any detectives yet, so I wanted to make it even more defined as a detective novel like The Maltese Falcon or Raymond Chandler books. So basically, then he said, ‘Yeah, that sounds great! No problem, I trust you. Just work out a story and show it to me.’

So Chris [Bateman] had come on at the end of Discworld II, so I went through that the high-level story stuff and the films and a couple of things with him. Chris wasn’t a comedy puzzle guy. He was more of a normal puzzle story guy, so he did puzzle things based on more subtle parody and satire. I provided some hangers and some things for him to hang stuff on and he went away and fleshed it all out and did the dialogue for that as well.

In the first two games, we made sure the scriptwriter could emulate Terry’s style as much as he could, but it didn’t matter in Discworld Noir because it was an original take. So the voice was original. It wasn’t so much Terry’s voice we were trying to emulate for the conversations and stuff as a new sort of noir take on the Discworld. Then we mixed in the horror stuff. That was already there from the start because we wanted to try a new technique with the sniffing and smelling and whatever – try something to add to the detective stuff — which was the werewolf stuff.

Time Extension: Was there any aspect of Discworld that you would have liked to have gone deeper on? Maybe like the Pyramids side and Small Gods? Or maybe some of the assassins’ stuff? Were there any other aspects of Discworld that you were hoping you would eventually get round to in a game?

Barnett: I spoke to Rhianna Pratchett a few years back now. Unfortunately, before Terry passed away, him or his agent or somebody had signed off every property to either ITV or Prime or BBC literally across the board. Even Rhianna was having a bit of trouble because she was trying to script some of the Susan books, I think.

Subscribe to Time Extension on

I did ask her because I said, ‘I would like to do a definitive game on the Guards but she said, ‘Unfortunately, they are making a TV show of it’. At the time, I had some really innovative ideas on how to use all of the guards as different detectives with their own particular abilities – you had the werewolf, you had the vampire, you had the dwarf, and so on and so on. That was where I wanted to go all the way just do a procedural detective thing. Not a noir thing but a proper procedural detective thing with the withes and the guards and whatever.

So that would have been the one thing that I would have liked to have done. It’s not the most fantastic thing if you’ve seen the other books, but it was just something where Terry had done so much foundational work so it just would have been great to have done something. And if you approached the people who made the TV series, they’re going to want it in the image of the TV series, which is the image I won’t do it in anyway.

Time Extension: There are a lot of companies now that do re-releases of old games. A lot of their work is detective work to find out who was involved in certain deals to try and track down rights. I know Rhianna herself has said nobody really knows who owns the rights to the original games. I’m wondering, has anyone approached you to try and track down that paperwork and see about rereleasing these games on modern hardware?

Barnett: Yeah! We are a little bit beyond that point. I don’t want to give you a scoop, but a Discworld rerelease may happen. The original rights are complicated in the UK, but it turns out that 50% reverted to me as the creator because the company Perfect Entertainment had been closed for over 10 years.

The Watch was a 2020 adaptation of Pratchett's Guards novels from BBC Studios. Upon release, it was unpopular with many fans of Pratchett's work, who criticized its deviations from the books and lack of charm — Image: BBC

Whenever something closes in the UK, intellectual property rights revert 50% to the original creator and 50% to the crown, which is King Charles. So that’s the two owners of the games. So yes, there have been discussions and something may be happening down the track – a rerelease or a remaster. But it’s obviously a complicated process when you’re dealing with the crown.

Time Extension: Yeah, it would be interesting to see them be re-released. At the moment, it requires a bit of googling to get those up and going again, so it would be interesting to see them thrown open to anyone that just loves Discworld and doesn’t want to do a ton of research on forums to find out how to get their old copies up and running.

Barnett: Yeah, hopefully that will happen. It’s on the cards. It may happen. And then it could advance to new versions of them. And again, I said, I would like to do a new Discworld game. But beyond all of the stuff that may or may not happen [like] the old versions, it’s just going to be hard to get the rights to do anything new in the Discworld universe at the moment.

https://store.steampowered.com/news/app/1902850/view/6636686753320883246

new game from Dreams in the Witch House dev announced

new game from Dreams in the Witch House dev announced

> Finnish Cultural Foundation

> Dunwich Horror

yes, I see

> Dunwich Horror

yes, I see

more sneedcraft shit

- Joined

- Aug 13, 2017

- Messages

- 1,685

released

Spirit Hunter: Death Mark II

Spirit Hunter: Death Mark II

Modron

Arcane

- Joined

- May 5, 2012

- Messages

- 11,162

Did the previous game have side scrolling adventure segments? I thought it was just a vn.

![Have Many Potato [2013] Codex 2013](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_potato2013.png)