Wot I Think: Vampyr

“Forget everything you think you know about vampires,” the noblewoman in period dress tells me, in her straight-out-of-

Hammer cut-glass accent. This was during our latest night-time meeting (for we cannot walk in sunlight), shortly after I’d caught her secretly sinking her teeth into the necks of the dispossessed, and shortly before I’d been beset by agony upon trying to enter a church. I don’t know what foolish notions her ladyship thought I had about my new status as a fellow vamp – maybe that they all have Welsh accents, or drink blood via their toenails – but ambitious, atmospheric fangs ‘n’ conversation game

Vampyr doesn’t often veer far from the current neck-biter hymn sheet.

It sure does veer in almost every other respect, mind you. I’m not sure that 2018 will yield many games quite as expansive as Vampyr, but what I wouldn’t give for a director’s cut that oiled its creakiest coffin hinges.

Vampyr comes from the folks behind delightful narrative adventure

Life Is Strange. That game’s big decision-making and casual sleuthing pumps clearly through Vampyr’s veins, though its hefty combat element shares a bloodline with LIS predecessor

Remember Me. The other major DNA strand, as quite a few of us have prayed for, is revered 2004 undead-noir RPG

Vampire: The Masquerade – Bloodlines. Vampyr similarly explores the uncomfortable realities of mortals and immortals secretly sharing a world, but very rarely is it either so playful or harrowing about it.

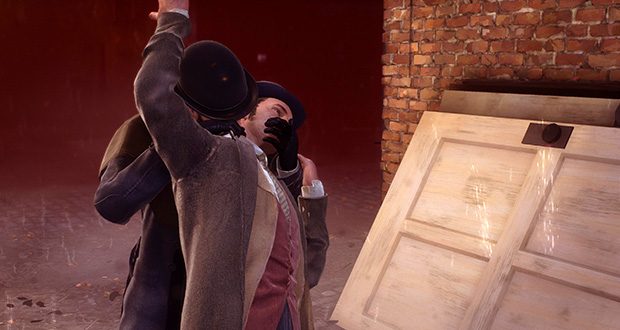

Vampyr plays out in a sickness ‘n’ monster-plagued London, just after the Great War. Dr Jonathan Reid is stricken with an aversion to sunlight and a thirst for the red stuff, and in turn must investigate supernatural conspiracy while upholding his medical duties during a city-wide epidemic. Whether he becomes a wanton killer, a needs-must brutal hero or a combat-avoidant investigator is up to you.

In theory. Many of Vampyr’s main plot beats are surprisingly inflexible, but offset by occasional big moral dilemmas expressed with all the clarity of someone singing

Mahna Manha into a blocked drain pipe. Imagine playing Dishonored, being careful to never kill or be caught. All that hard work of sneaking and silent throttling, but then, at the end of the mission, you have to play a round of Find The Lady to determine whether the district you so cautiously moved through embraces peace and liberty or becomes a wasteland of corpses and plague. (Or vice-versa – malevolent play, happy outcome).

In Vampyr, all your conversations, all your dealings with the petty concerns of mortals, all your hours spent scouring an ever-twilight and labyrinthine London and engaging in tricky fights that play out a little like a baby Bloodborne come down to a conversational lottery at the end of each ‘act.’ Choose unluckily and you’ll incite almost comically melodramatic outcomes not remotely implied by the vague dialogue choices offered. The main plot does at least march on, broadly keeping this carnage off to one side of it, but it’s nonetheless a gut-punch to, say, instantly lose major NPCs.

Vampyr’s checkpoints-only, single savefile system (i.e. you cannot load an older save) means I’m unable to experience less ludicrous outcomes without a total do-over. I respect the integrity of this, in a ‘you break it, you bought it’ sort of way, but I don’t think I’d rush to do it all again. This is not, like LIS, an episodic game you can revisit in fenced-off chunks. There will be clamouring for a full-fat save system soon after Vampyr’s release, and it should be heeded, whether or not it involves diluting the purity of its creative blood.

Maybe Vampyr consciously embraces the butterfly effect here, despite spelling most everything else out at great length, or maybe its writing needs another pass. Certainly, smaller things have been lost in translation. While the dialogue as a whole is solid (if overly dour), the subtitles are gently peppered with errors, the occasional line sounds mangled, and too often an excess of bone-dry exposition takes precedence over personality.

All the same, Vampyr has glamoured me enough to persist past a few rage-quits spurred by these absurd outcomes. This is a huge and agreeably grim world, full of dark corners to investigate, soaking up the hours with a frothy mix of exploration, tense fights and slow-burn clue-hunting. I mentioned Dark Souls offshoot Bloodborne earlier, and Vampyr sups from its holy veins in a way beyond vaguely shared (though infinitely less imaginative here) Gothic aesthetics. This London is a dark maze of danger spots and safezones, mentally-mapped and short-cutted by repeat exploration and growing strength.

Though the combat isn’t anything like as unforgiving, it’s satisfyingly tactical, complex and requires careful specialisation. You could be a pure, stamina-rich brawler, or someone deft at dazing foes so they can move in for uninterrupted neck-bites, someone whose every attack gains them Blood that can be used to activate special, monstrous attacks, someone who’s constantly self-healing and shrouding themselves in mystic barriers…

A strong spec and growing familiarity with how to combo your various skills and weapons means you can take down foes far tougher than you. I’ve snarled in fury at my umpteenth death to an overpowered boss, but I’ve done so knowing that this was a genuine test of skill, rather than thinking it unfair. I suspect anyone picking up Vampyr because of LIS is most anticipating the choice ‘n’ consequence side of things, as I was, but I came away most enraptured by the combat. You’ll want a gamepad, however – mouse and keyboard don’t feel good here.

Despite all the killing, I have striven to be good. In my mind, I’m roleplaying as a noble vamp who only kills when attacked, and once in a while secretly slays those who inflict suffering upon others (a racist slum landlord, for instance). There are some consequences, but it’s to Vampyr’s credit that it doesn’t have anything as overt as a ‘humanity meter’: this is a more internal kind of character-building, being the person I want to be, as opposed to one who tries to game the system. Being good is a state of mind, rather than a path to obvious rewards, while being bad results in eerily depopulated areas: a more powerful consequence than a lurid cutscene or a cancelled mission objective. Still, I sometimes felt that my choices what manner of man/beast I am were met with barely a shrug, at least until late denouements, because Vampyr was too busy telling a fixed tale.

This is not full the personality-shaping of Bloodlines’ conversations, but rather the main character is akin to LIS’ Max or a Telltale hero: fixed but with some flexibility. I’d be more on board with this if vamptagonist Jonathan was more interesting: his persistent formality might reflect the stiff-upper-lip era, but he’s a bit of a wet blanket, plus the game frequently makes him (me) say and do things I never would have chosen to myself. I could not, for instance, object to a secret cartel of society-manipulating jingoists, because the plot demanded that I join them for a while. So often in Vampyr I wanted to tell someone they were being a colossal penis, or to mediate between entrenched, extreme positions, but the story is the story.

More appealing is the uncomfortable paradox of Jonathan being both a blood-supping terror and a dedicated medical professional, though the more fascinating elements of this are lost in the ongoing din of exposition. A further layer to the game has you regularly dashing around disease-ridden London boroughs, offering remedies to put-upon NPCs for their fatigue, cold and migraine, which in theory affects shop prices and XP opportunities, but too often feels like tacked-on busywork that’s a repetitive alternative to meatier reputation-building missions. Whenever you ‘rest’ to spend XP on skill upgrades, the boroughs’ denizens gain new afflictions, necessitating mixing up more meds and another long-winded sprint through oft-trodden streets. Between this schlepp and my exasperation at the moral dilemma lottery, I increasingly let boroughs slide into chaos – the dark side is easier and with its own rewards, though it isn’t where I wanted to be.

The supporting cast left few puncture marks upon my neck either – anyone hoping for a Chloe is going to be disappointed here, let alone a

Jeanette or

Heather. More impressively (and appropriate to the setting) it does engage with the issues of the in-game day – medical ethics, war trauma, the nascent women’s rights movement, the class and race divide (much of which has painful relevance in 2018). Like so much else in Vampyr’s tale, most of this involves grim faces telling rather than showing via deed or force of personality, so I’m not sure how many blows are landed, but I appreciate the attempt to be more than a grisly supernatural saga.

Perhaps fittingly, people are ultimately resources. Uncovering their secrets (broadly via dialogue with the characters around them) boosts the XP granted if you decide to drink their blood, or you can rack up a smaller amount of points by completing various fetch or rescue quests for some of them. You don’t

have to drink blood, but you’ll be about as fearsome as Milhouse going trick or treating if you don’t. Vampyr’s most compelling aspect, for me, was straddling the line between being strong enough to survive and not becoming a wanton murderer. Diligent looting, side-questing and tactical monster-battling can see you through without having to turn to open psychopathy, if you’re willing to put the hours in.

You can avoid most combat, though you need to know you’re doing this from the start if you want certain endings. It’s a fiendishly tricky business, as anywhere other than conversation and quest hubs is patrolled by a mix of instantly-aggressive vampire hunters and ‘skal’, a low-grade, bestial vampternative. You can eventually spec out your character with invisibility and self-protection skills in order to dash past these guys without dying every time, but the stealth systems are rudimentary and clunky, making this hard and repetitive graft that I would say is best left to achievement hunters. Playing like this also means gaining minimal XP, leaving you in a tricky spot for the mandatory boss fights.

I do love that there’s this profoundly different way of playing, but, unusually for me, the open fisticuffs playstyle thrilled me in a way the hiding and running one did not – and in any case, the boss fights mean you cannot remain a pure pacifist.

My surprise with Vampyr is that I’ve enjoyed it as a combat game much more than I have a chat ‘n’ choice one – the exact opposite of what I’d have expected from the makers of Life Is Strange. The characters rarely sparkle, the biggest choices are too much of a lottery, and there’s little tension around the vampiric conceit – blood-drinking is a nonchalant option, not a desperate

thirst as it is repeatedly described. And, despite that noblewoman’s bold assertion that we should not expect the befanged expected, there is very little freshness to this exploration of the undead condition. Although I do enjoy the griminess, the filth and the viscera of its world. An exaggerated squalor, perhaps, but there is a real sense that this London is only moments away from total collapse.

I’m frustrated that Vampyr falls just short of truly combining a smart choose-your-own-adventure game with a meaty action one. It’ll never happen, but a director’s cut that thins the sombre exposition and eases the medical busywork, injects more pep, and makes decisions decisions, rather than often either a roulette wheel or a railroaded path, would create a dream combination of darkness and light. Nonetheless, as a sprawling midnight world of tight fights and atmospheric exploration, this is a fat vein I keep returning to.